Abstract

The μ-conotoxin μ-KIIIA, from Conus kinoshitai, blocks mammalian neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) and is a potent analgesic following systemic administration in mice. We have determined its solution structure using NMR spectroscopy. Key residues identified previously as being important for activity against VGSCs (Lys7, Trp8, Arg10, Asp11, His12 and Arg14) all reside on an α-helix with the exception of Arg14. To further probe structure-activity relationships of this toxin against VGSC subtypes, we have characterised the analogue μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], in which the Cys residues involved in one of the three disulfides in μ-KIIIA were replaced with Ala. Its structure is quite similar to that of μ-KIIIA, indicating that the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide bond could be removed without any significant distortion of the α-helix bearing the key residues. Consistent with this, μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] retained activity against VGSCs, with its rank order of potency being essentially the same as that of μ-KIIIA, namely, NaV1.2 > NaV1.4 > NaV1.7 ≥ NaV1.1 > NaV1.3 > NaV1.5. Kinetics of block were obtained for NaV1.2, NaV1.4 and NaV1.7, and in each case both kon and koff values of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] were larger than those of μ-KIIIA. Our results show that the key residues for VGSC binding lie mostly on an α-helix and that the first disulfide bond can be removed without significantly affecting the structure of this helix, although the modification accelerates the on- and off-rates of the peptide against all tested VGSC subtypes. These findings lay the groundwork for the design of minimized peptides and helical mimetics as novel analgesics.

Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) play key roles in the electrical excitability of cells by regulating the influx of sodium ions. In mammals, nine different subtypes (NaV1.1–1.9) have been identified, each with different distributions in the body (1). Of particular interest are the neuronal subtypes as several have been implicated in the perception of pain (2). As such, modulators of these subtypes may have potential therapeutic use as analgesics. Many peptide toxins have evolved to target VGSCs with high selectivity and potency (1, 3). Toxins such as ProTx-II from spiders or μO-MrVIB from marine cone snails not only provide novel analgesics but they also define novel binding sites for future development of small molecules (4–7). Another group of sodium channel-blocking toxins, some of which possess analgesic activity, is the μ-conotoxins, which bind to the extracellular side of the pore (site 1) and occlude the passage of sodium ions through the pore (8, 9).

The conotoxin μ-KIIIA from Conus kinoshitai belongs to a new class of μ-conotoxins that selectively blocks tetrodotoxin(TTX)-resistant VGSCs in amphibians, unlike previously characterized μ-conotoxins, which are selective for TTX-sensitive Na+ channels (10). Recently, it was shown that μ-KIIIA blocked several subtypes of mammalian neuronal VGSCs and displayed potent analgesic activity following its systemic administration in mice (11). A study of structure-activity relationships in μ-KIIIA identified key residues important for its activity on the mammalian neuronal NaV1.2 and skeletal muscle NaV1.4 subtypes, and demonstrated that the engineering of μ-KIIIA could provide subtype selective therapeutics against mammalian VGSCs for the potential treatment of pain (11).

In developing more effective analgesics for the treatment of pain, peptides with higher subtype selectivity are of considerable interest, but it is also desirable to design minimized analogues with the aims of enhancing bioavailability and potency (12). μ-KIIIA is a particularly attractive ligand in these respects as it is already the smallest known μ-conotoxin, having only one residue in the first inter-cystine loop, as compared with five in most of the μ-conotoxins, in addition to lacking the two residues preceding the first cysteine residue in the N terminus (Figure 1A). In designing minimized peptides it is important to compensate for the presence of structure-stabilizing disulfide bridges that may be removed in the process of pruning. However, in peptides with multiple disulfide bridges, not all of them are necessarily crucial for maintaining structure and activity (13–16). The role of the disulfide bonds in μ-KIIIA was investigated by eliminating individual disulfide bridges and testing each of the disulfide deficient analogues against mammalian NaV1.2 and NaV1.4 (17). Removal of the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide bond did not significantly alter the biological activity against either VGSC subtype, while removal of the Cys2-Cys15 bridge reduced activity and deletion of the Cys4-Cys16 bridge eliminated activity. The structural consequences of removing the individual disulfide bonds, however, have not been analyzed experimentally.

Fig. 1.

(A) Amino acid sequences of μ-conotoxins belonging to the μ-KIIIA class [μ-KIIIA (10), μ-SIIIA (10, 44), μ-SmIIIA (37), μ-CIIIA (45), μ-MIIIA (45) and μ-CnIIIA (45)]. Z represents pyroglutamate in the sequences of μ-SIIIA, μ-SmIIIA and μ-MIIIA. (B) Amino acid sequences of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] with the disulfide connectivities indicated. All peptides are C-terminally amidated, as denoted by the asterisk (*).

In this study, we have determined the solution structure of μ-KIIIA and the structural consequences of removing the first disulfide bond (Cys1-Cys9) of μ-KIIIA by also determining the structure of its analogue, μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] (Figure 1B). We further characterized structure-activity relationships of μ-KIIIA by determining the activity of the disulfide-deficient analogue against a range of mammalian VGSC subtypes. Our work shows that removal of the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide only minimally affected the structure and function of this peptide, thus opening the way for further developments in the design of μ-conotoxin mimetics.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and oxidative folding

Peptides were synthesized using standard N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry. The peptides were cleaved from the resin by 3–4 h treatment with reagent K (TFA/water/ethanedithiol/phenol/thioanisole; 82.5/5/2.5/5/5 by volume). The cleaved peptides were filtered, precipitated with cold methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and washed several times with cold MTBE. The reduced peptides were purified by reversed-phase HPLC using a semipreparative C18 Vydac column (218TP510, 10 mm × 250 mm) eluted with a linear gradient from 5 to 35% solvent B in 35 min, where solvent A was 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water, and B was 0.1% (v/v) TFA in 90% aqueous acetonitrile (ACN). The flow rate was 5 ml/min, and absorbance was monitored at 220 nm.

To prepare μ-KIIIA analogues with the native disulfide connectivity, the first cysteine pair was protected by S-trityl groups and the second pair was protected by acetamidomethyl groups. To oxidize the first disulfide bridge, the reduced peptides (at 20 μM final concentration) were dissolved in 0.01% TFA and added to the folding mixture containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and 1 mM reduced glutathione (GSH). The reactions were carried out at room temperature. After 1 h, the reactions were quenched with formic acid (8% final concentration) and purified by semi-preparative HPLC as described above. To remove the acetamidomethyl groups from the second pair of cysteines and close the remaining disulfide bridge, the peptides were treated with 2 mM iodine in 50% aqueous acetonitrile for 10 min and quenched with ascorbic acid. The analytical HPLC gradient was linear from 5 to 35% solvent B over 35 min, where solvent A was 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water, and B was 0.1% (v/v) TFA in 90% aqueous acetonitrile. The flow rate was 1 mL/min. The identities of final products were confirmed by MALDI-TOF analysis.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were recorded on a 2.6 mM solution of μ-KIIIA (pH 2.9 and 4.8) and 3.7 mM solution of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] (pH 3.2 and 5.3) in 94% H2O / 6% 2H2O and 95% H2O / 5% 2H2O, respectively. For each of the peptides, a series of one-dimensional spectra at 5 °C intervals was collected over the temperature range 5–25 °C. Two-dimensional homonuclear total correlation (TOCSY) spectra with a spin-lock time of 70 ms, nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOESY) spectra with mixing times of 50 and 250 ms, and double quantum filtered correlation (DQF-COSY) spectra were acquired at 600 MHz on a Bruker DRX-600 spectrometer. NOESY spectra (250 ms) were also recorded at 20 °C for both peptides to confirm assignments in the event of peak overlap. In addition, 1H-13C HSQC spectra for the assignment of 13C chemical shifts were collected at 5 °C on the Bruker DRX-600, and 1H-15N HSQC spectra for the assignment of 15N chemical shifts (18, 19) were collected on a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer equipped with a TXI-cryoprobe. Diffusion measurements were performed at 5 and 20 °C using a pulsed field gradient longitudinal eddy-current delay pulse sequence (20, 21) as implemented by Yao et al. (22). The water resonance was suppressed using the WATERGATE pulse sequence (23). Amide exchange rates were monitored by dissolving freeze-dried material in 2H2O at pH 5.2 for μ-KIIIA and pH 4.2 for μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], then recording a series of 1D spectra, followed by a 70 ms TOCSY and a 50 ms NOESY. All spectra were acquired at 5 °C unless otherwise stated and were referenced via the water resonance. Spectra were processed using TOPSPIN (Version 1.3, Bruker Biospin) and analysed using XEASY (Version 1.3.13) (24).

Structural constraints

3JHNHα coupling constants were measured from DQF-COSY spectra at 600 MHz, and then converted to dihedral restraints as follows: 3JHNHα > 8 Hz, ϕ = −120 ± 40°; 3JHNHα< 6 Hz, ϕ = −60 ± 40°. Five ϕ angles (Lys7-Asp11) were restrained in both peptides. χ1 angles for some residues were determined based on analysis of a short mixing time (50 ms) NOESY spectrum. Three χ1 angles (Cys4, Arg10 and His12) were constrained in final structure calculations of μ-KIIIA and one (Cys15) in μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. The final constraints are summarized in Table 1 and details have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (25) with accession numbers 20048 and 20049 for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], respectively.

Table 1.

Structural statistics for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]

| μ-KIIIA | μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] | |

|---|---|---|

| Distance restraints | 225 | 241 |

| Intra (i = j) | 97 | 100 |

| Sequential (| i − j | = 1) | 70 | 55 |

| Short (1 < | i − j | < 6) | 45 | 69 |

| Long | 13 | 17 |

| Dihedral restraints | 8 | 6 |

| Energies (kcal mol−1)a | ||

| ENOE | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| Deviations from ideal geometryb | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0017 ± 0.0002 | 0.0018 ± 0.0002 |

| Angles (°) | 0.503 ± 0.013 | 0.531 ± 0.017 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.371 ± 0.009 | 0.403 ± 0.016 |

| Mean global RMSD (Å)c | ||

| Backbone heavy atoms | ||

| All residues | 0.58 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.38 |

| Residues 5–16 [S(ψ), S(ϕ) > 0.8] | 0.45 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.11 |

| All heavy atoms | ||

| All residues | 1.42 ± 0.28 | 1.77 ± 0.42 |

| Residues 5–16 [S(ψ), S(ϕ) > 0.8] | 1.44 ± 0.31 | 1.55 ± 0.42 |

|

| ||

| Ramachandran plotd | ||

| Most favoured (%) | 78.9 | 76.1 |

| Allowed (%) | 21.1 | 22.9 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 0 | 1.1 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | 0 |

The values for ENOE are calculated from a square well potential with force constants of 50 kcal mol−1 Å2.

The values for the bonds, angles, and impropers show the deviations from ideal values based on perfect stereochemistry.

The pairwise RMSD over the indicated residues calculated in MOLMOL.

As determined by the program PROCHECK-NMR for all residues except Gly and Pro.

Structure calculations

Intensities of NOE cross peaks were measured in XEASY and calibrated using the CALIBA macro of the program CYANA (version 1.0.6) (26). NOEs providing no restraint or representing fixed distances were removed. The constraint list resulting from the CALIBA macro of CYANA was used in Xplor-NIH to calculate a family of 200 structures using the simulated annealing script (27). The 60 lowest energy structures were then subjected to energy minimization in water; during this process, a box of water with a periodic boundary of 18.856 Ǻ was built around the peptide structure and the ensemble was energy minimized based on NOE and dihedral restraints and the geometry of the bonds, angles and impropers. From this set of structures, final families of 20 lowest energy structures were chosen for analysis using PROCHECK-NMR (28) and MOLMOL (29). In all cases, the final structures had no experimental distance violations greater than 0.2 Å or dihedral angle violations greater than 5°. Structural figures were prepared using the programs MOLMOL (29) and PyMOL (Delano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (2002) Delano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA. http://www.pymol.org).

Comparative modeling and molecular dynamics

Models of μ-KIIIA and three disulfide-deficient analogues (μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], μ-KIIIA[C2A,C15A], μ-KIIIA[C4A,C16A]) were generated from the solution structure of the closely related μ-conotoxin μ-SmIIIA (PDB entry 1Q2J) using the Modeller (8v2) software (30) by homology modelling methods. The 20 experimental NMR structures of μ-SmIIIA (31) were used to generate the initial models based on the sequence alignment in Figure 1. For each initial alignment, 25 models were generated and from each of these 25 models, the model with the lowest Modeller Objective Function was used in the molecular dynamics (MD) calculations. Models of the three disulfide-deficient analogues were also generated using the solution structure of μ-KIIIA (determined in this study) as an initial template. Initial models of each analogue were constructed from the ensemble of experimental NMR structures of μ-KIIIA, and the structure with the lowest Modeller Objective Function was used in subsequent MD calculations. As the results for the three disulfide-deficient analogues were largely independent of which starting structure was used (μ-SmIIIA versus μ-KIIIA), only one set of structures (those starting from μ-KIIIA) are described in detail under Results.

MD simulations were conducted using the GROMACS version 3.3.1 package of programs (32) employing the OPLS-aa force field (33). The toxins were solvated in a box of water and the total charge of the system made neutral by replacing water molecules with chloride ions. The LINCS algorithm was used to constrain bond lengths (34). Peptide, water, and ions were coupled separately to a thermal bath at 300 K using a Berendsen thermostat (35) applied with a coupling time of 0.1 ps. All simulations were performed with a single non-bonded cutoff of 10 Å, applying a neighbor-list update frequency of 10 steps (20 fs). The particle mesh Ewald method was applied to deal with long-range electrostatics with a grid width of 1.2 Å and fourth-order spline interpolation. All simulations consisted of an initial minimization to remove close contacts, followed by 10 ps of positional restrained MD to equilibrate the water molecules with the polypeptide fixed. The time step used in all the simulations was 2 fs. MD simulations for each peptide were run for a total time of 50 ns. Structures were extracted from the trajectory of each MD simulation at time intervals of 0.2 ns. A comparison of the RMSD of the superposition of backbone atoms between all extracted structures is presented as heat maps (Figure S7), illustrating the structural variation observed during the simulations. Cluster analysis was performed using the method of Daura et al. (36) to select representative conformers sampled throughout the simulation.

Electrophysiology of mammalian NaV clones expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Oocytes expressing VGSCs were prepared and two-electrode voltage clamped essentially as described previously (11). Briefly, oocytes were placed in a 30 μL chamber containing ND96 and two-electrode voltage clamped at a holding potential of −80 mV. To activate VGSCs, the membrane potential was stepped to a value between −20 and 0 mV (depending on NaV subtype) for a 50 ms period every 20 sec. To apply toxin, the perfusion was halted, 3 μL of toxin solution (at ten times of the final concentration) was applied to the 30 μL bath, and the bath manually stirred for about 5 s by gently aspirating and expelling a few μL of the bath fluid several times with a pipettor. Toxin exposures were in static baths to conserve material. On-rate constants were obtained assuming the equation kobs = kon•[peptide] + koff (37), where kobs was determined from the single-exponential fit of the time course of block by a fixed concentration of 1 μM peptide, and koff determined from single-exponential fits of the time course of recovery from block following toxin washout. All recordings were made at room temperature (~21 °C).

Results

NMR spectroscopy

Good quality spectra were obtained for both μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. Broad NH chemical shift dispersion for both peptides indicated that both were well structured and adopted a single major conformation in solution. The amide and aromatic regions of 1D spectra of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] at different temperatures are shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information and the fingerprint regions of TOCSY and NOESY spectra in Figure S2. Chemical shift assignments are presented in Tables S1 and S2, and have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (25) with accession numbers 20048 and 20049 for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], respectively. Distance restraints were obtained from the intensities of the NOE cross-peaks at 5 °C and pH 4.8 for μ-KIIIA and 5 °C and pH 5.3 for μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], with NOESY spectra at higher temperature and lower pH being used to resolve peak overlap.

Self-diffusion coefficients of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] at 5 °C are (1.71±0.03) ×10−10 m2 /s [SD over 12 resonances] and (1.80±0.09) ×10−10 m2 /s [SD over 8 resonances], respectively. These values were similar to that of α-RgIA (38), a 13 residue α-conotoxin with a well-defined structure. Extrapolated values were comparable (ca 18% faster) to those obtained for peptides studied by Yao et al. (22) indicating that both μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] were monomeric and structurally compact in solution.

Deviations of the backbone NH and Hα chemical shifts of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] from random coil values (39) are plotted in Figure 2. The similarities in the pattern of deviations confirm that they adopt similar backbone structures. Differences in backbone NH and Hα chemical shifts between μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] are also plotted, the largest deviations occurring at the N and C-termini, as well as the region around residue 9. The perturbations of Ser13, Arg14, Cys15 and Cys16 imply that the C-terminal region is slightly affected by removal of the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide, presumably because of the proximity of the N- and C-termini engendered by the Cys2-Cys15 disulfide (see below).

Fig. 2.

Chemical shift deviation of backbone amide and Cα protons from random coil values at 5 °C (39) for (A) μ-KIIIA and (B) μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. Random coil values for oxidised Cys residues were obtained from Wishart et al. (46) (C) Chemical shift difference of backbone amide and Cα protons between μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] at 5 °C.

Solution structures

A summary of experimental constraints and structural statistics for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] is given in Table 1. The angular order parameters for ϕ and ψ in the final ensemble of 20 structures for μ-KIIIA were both > 0.8 over all residues (Figure S3), indicating that these backbone dihedral angles are well defined across the family of structures. For μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], the corresponding angular order parameters were > 0.8 over residues 5–16. The mean pairwise RMS differences over the backbone heavy atoms over all residues for the families of structures of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] were 0.58 Å and 0.97 Å, respectively. Over residues 5–16, the RMS differences were 0.45 and 0.54 Å, respectively (Figure 3). The closest-to-average structures of both μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] are characterized by an α-helix from Lys7 to His12, which was present in 16 out of 20 structures of μ-KIIIA and 18 out of 20 structures of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. The presence of medium-range NOEs [dαN(i,i+3) and dαN(i,i+4)] in this region supports the helix observed (Figure S4). The locations of side chains in the families of structures are shown in Figure S5. Hydrogen bonds were observed from Arg10 NH to Ser6 O and from Asp11 NH to Lys7 O in all 20 structures of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. Hydrogen bonds from Arg10 NH to Ser6 O were observed in all 20 structures of μ-KIIIA, while Asp11 NH to Lys7 O hydrogen bonds were observed in 18 out of 20 structures.

Fig. 3.

Stereo views of family of 20 final structures for (A) μ-KIIIA and (B) μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] superimposed over backbone heavy atoms (N, Cα, C′) over residues 5–16 with disulfide bonds shown in gold.

Comparison of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]

Figure 4 shows a superposition of the closest-to-average structures of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] over the backbone heavy atoms of residues 5–16. The backbones generally align well over these residues, with a pairwise RMSD of 0.95 Å, and adopt a very similar secondary structure, with an α-helix from residues 7–12. The key residues for VGSC binding identified by Zhang et al. (11) (Lys7, Trp8, Arg10, Asp11, His12 and Arg14) mostly lie in the α-helical region and occupy similar positions in μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], although the orientation of the Trp8 and His12 side chains differs slightly between the two peptides. This difference between the relative orientations of these two key side chains may reflect differences in the NOE restraint sets for the two peptides as a result of peak overlap, since the side chain chemical shifts, which are a sensitive indicator of local environment, especially for aromatic side chains, are very similar for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] (Tables S1 and S2).

Fig. 4.

Stereo views of the closest-to-average structures of (A) μ-KIIIA and (B) μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] with all side chain heavy atoms displayed and labelled. Disulfide bonds are shown in gold; positively charged residues are coloured blue, negatively charged red, hydrophilic green and aromatic magenta. (C) Structural overlay of the closest-to-average structures of μ-KIIIA (green) and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] (purple) over the backbone heavy atoms of residues 5–16. Disulfide bonds are shown in gold and side chains of key residues are shown, positively charged residues coloured blue and negatively charged in red. The two views are related by a 180 ° rotation about the vertical axis.

Structurally, the main difference lies in the conformation of the N terminal region, which, in μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], is no longer constrained by a disulfide bond to the α-helical region and, as a result, appears to be more flexible. A comparison of the number of NOEs (Figures S2 and S3) in the N-terminal region showed that μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] had fewer NOE restraints for residues 1–3 than μ-KIIIA, although a greater total number of distance restraints was obtained for μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] because of its higher concentration compared with μ-KIIIA. Peak overlap of amide resonances from residues 2–4 in the μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] NOESY spectrum complicated an accurate comparison of N-terminal (residues 1–4) NOEs in the two spectra, but strong sequential NOEs from the amide of Cys2 to Cβ protons of Cys1 and a long-range NOE from the amide of Asn3 to the Cβ proton of Cys9 seen in the μ-KIIIA spectra were clearly absent in the spectrum of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] (Figure S2). To confirm that the disorder observed in the N-terminal of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] was not simply the result of a lack of NOEs, other parameters were also compared. As mentioned above, the backbone 1H chemical shifts indicated significant differences in the N-terminal region (Figure 2). A comparison of 13C chemical shifts (Figure S6) gave similar results, consistent with a change in conformation of both the N-terminal and C-terminal regions as a result of removal of the disulfide bond. Finally, 3JHNHα for Cys4 in μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] was >8 Hz, as compared to 6.1 Hz for the same residue in μ-KIIIA, suggesting a more extended conformation for this residue in μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] than in μ-KIIIA.

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics simulations on μ-KIIIA and each of the disulfide-deficient analogues were conducted to examine the likely structural consequences of removing individual disulfide bonds. Figure 5 shows a comparison of the representative structures sampled throughout the 50 ns of MD simulations of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] with the ensemble of NMR-determined structures. The comparison shows that for both peptides the ensemble of MD simulated structures adopted a similar overall fold to the experimentally derived structures. Similar results (not shown) were obtained using models that employed μ-SmIIIA as a template in the comparative modeling of the structures used to initiate the MD calculations. The conformity of these results highlights the utility of comparative modeling and molecular dynamics in structural studies of small toxins.

Fig. 5.

Stereo views of (A) representative MD structures (red) and NMR structures (grey) of μ-KIIIA; (B) representative MD structures (magenta) and NMR structures (grey) of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A]. Structures are superimposed over backbone heavy atoms (N, Cα, C′) over residues 4–16. The MD structures of μ-KIIIA were generated using μ-SmIIIA as a starting structure, whereas those for μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] were generated from the μ-KIIIA structure determined experimentally in this study.

The structural variability of each peptide during the MD simulation is presented as RMSD plots (Figure S7). The RMSD plot for μ-KIIIA indicates this peptide is significantly less flexible, and therefore explores less conformational space than the other peptides. The most representative structure from the MD simulations of each peptide is shown in Figure S8. For μ-KIIIA, μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] and μ-KIIIA[C2A,C15A] an α-helix was observed from Lys7 to Asp11 or His12. The structure of μ-KIIIA[C4A,C16A] showed the largest variation of all the peptides; during the latter half of the MD simulation the helix was replaced by random coil, yielding a structure with a very different, albeit relatively stable, conformation compared with the other three peptides.

Functional activity in blocking VGSCs

The ability of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] to block cloned α-subunits of rat (r) or mouse (m) sodium channels expressed in oocytes was assessed by voltage-clamp protocols. The peptide was shown recently to readily block NaV1.2, a neuronal subtype, and NaV1.4, a skeletal muscle subtype (17); here we have investigated five additional channel subtypes. Table 2 summarizes the activity of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] against all seven VGSC subtypes tested, including neuronal subtypes NaV1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.6 and 1.7 and the heart muscle subtype rNaV1.5. In addition to rNaV1.2 and 1.4, mNaV1.6, and rNaV1.7 were readily blocked by μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], with estimated Kd values ranging from 8 nM to 1.1 μM, while the remaining NaV subtypes were minimally blocked. To conserve material, the Kd values shown in Table 2 were estimated from the kinetics of block and recovery employing a single concentration (1 μM) of peptide; this appears to be justified insofar as the Kd values were all within a factor of three of the IC50 values predicted from steady-state block (cf. second column of Table 2), assuming the Langmuir absorption isotherm, % Block = 100 × plateau/[1 + (IC50/[toxin])]. The value used for plateau was 1.0 in all cases except NaV1.2, where 0.95 was used instead since a 5% residual current is observed with saturating concentrations of μ-KIIIA on NaV1.2 (40) and assuming μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] has a similar residual current. The predicted IC50 values were 0.022, 0.18, 0.22 and 2.7 μM for NaV1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.7, respectively.

Table 2.

Block by 1 μM μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] of cloned VGSCsa.

| Channelb | % Blockc | kobs (min−1) | koff (min−1) | kond (μM•min)−1 | Kde (μM) | μ-KIIIA Kdf (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rNaV1.1 | 3 ± 2 | N.A.g | N.A. | -- | -- | 0.29 ± 0.11 |

| rNaV1.2 | 93 ± 2 | 1.8 ± 0.39 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 1.8 ± 0.39 | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.005 ± 0.005 |

| rNaV1.3 | 7 ± 2 | N.A. | N.A. | -- | -- | 4.6 ± 1.5 |

| rNaV1.4 | 85 ± 2 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.78 ± 0.1 | 3.22 ± 0.51 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.016 |

| rNaV1.5 | 1 ± 2 | N.A. | N.A. | -- | -- | -- |

| rNaV1.6 | 82 ± 2 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.08 ± 0.015 | 0.4 ± 0.071 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | --h |

| mNaV 1.7 | 27 ± 1 | 0.72 ± 0.4 | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 0.35 ± 0.41 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 0.29 ± 0.09 |

Values (mean ± s.d., n ≥ 3) were obtained by two-electrode voltage clamp of Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned channels as described in Methods and Materials. Results for rNaV1.2 and rNaV1.4 are from Han et al. (17).

α-Subunit cloned from rat (r) or mouse (m).

Steady-state block of peak sodium current.

From [kobs − koff].

From koff/kon.

Values for wild-type μ-KIIIA are from Zhang et al. (11).

Unable to be determined because block was too small and apparent kinetics too fast for accurate measurement.

Block of NaV1.6 by wild-type μ-KIIIA was only partially reversible and precluded Kd determination (11).

Based on % block and/or Kd values, the disulfide-deleted peptide blocked NaV1.2 best, with the following rank order of potency: rNaV1.2 > rNaV1.4 ≈ mNaV1.6 > rNaV1.7 > rNaV1.1 ≈ rNaV1.3 > rNaV1.5. For comparison, the previously determined Kd values of wildtype μ-KIIIA are also listed in Table 2; its rank order of potency is rNaV1.2 > rNaV1.4 > rNaV1.1 ≈ rNaV1.7 > rNaV1.3 > rNaV1.5 (mNaV1.6 is absent because its block was only partially reversible) (11). μ-KIIIA blocked rNaV1.2, 1.4, and 1.7 with kon values of 0.3, 0.97, and 0.024 μM−1•min−1, respectively, and koff values of 0.0016, 0.047, and 0.007 min−1, respectively (11). Comparison of these values with those of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] in Table 2 reveal that, in each case, the disulfide deletion increased both kon and koff of the peptide.

Discussion

In this study, we have determined the solution structures of μ-KIIIA and its disulfide deficient analogue μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] in order to investigate the structural and functional consequences of removing the first disulfide bond (Cys1-Cys9). We begin by comparing the structure of μ-KIIIA with those of the closely-related μ-conotoxins, μ-SIIIA and μ-SmIIIA, then consider the implications of our findings on the effect of disulfide deletion for generation of minimized analogues and mimetics of μ-KIIIA.

Comparison of μ-KIIIA with μ-SIIIA and μ-SmIIIA

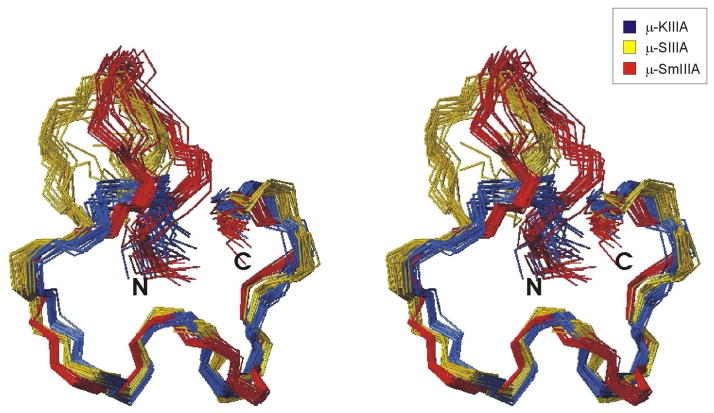

μ-KIIIA was characterized previously as belonging to the same class of μ-conotoxins as μ-SIIIA and μ-SmIIIA, with the three peptides having an essentially identical C-terminal region but differing in the length of the first N-terminal loop (10) (Figure 1). In that study, molecular dynamics simulations were used to model the structures of μ-KIIIA and μ-SIIIA from μ-SmIIIA and to analyse the structural consequence of altering the number of residues in the first loop (10). The solution structure of μ-SmIIIA was described a few years ago by Keizer et al. (31), while the solution structure of μ-SIIIA has been determined recently by two different groups (41, 42). Comparing the solution structures of these three μ-conotoxins confirmed the results of the MD simulations in that the number of residues in the first loop did not affect the overall conformations of the second and third loops (10). Superimpositions of the three structures over the backbone heavy atoms of the second and third loops (residues 4–16 of μ-KIIIA) gave a mean global pairwise RMSD of 0.92 Å, with μ-KIIIA being more similar to μ-SIIIA (group RMSD 0.88 Å) than μ-SmIIIA (group RMSD 1.34 Å), as illustrated in Figure 6. As in μ-KIIIA, the secondary structures of μ-SIIIA (41, 42) and μ-SmIIIA (31) were characterized by an α-helix corresponding to residues 7–12 of μ-KIIIA, although in μ-SmIIIA this helix was somewhat distorted. As expected, the main difference lies in the length of the first inter-cysteine loop towards the N-terminal, which, in all three peptides, is oriented away from the C-terminal region. This is in marked contrast to the solution structure of μ-SIIIA described recently by Schroeder et al. (41), which shows this loop projecting inwards, under the Cys4-16 disulfide bridge and towards the α-helix. As the structural statistics for this structure were not published and the structure is not available from BMRB, a detailed comparison with the other structures is not possible.

Fig. 6.

Stereo views of families of 20 final structures of μ-KIIIA (blue), μ-SIIIA (yellow) [BMRB accession number 20023] and μ-SmIIIA (red) [PDB ID 1Q2J] superimposed over backbone heavy atoms (N, Cα, C′) of residues 4–16 for μ-KIIIA (residues 8–20 for μ-SIIIA and residues 10–22 for μ-SmIIIA).

Key residues lie on an α-helix

Our structure of μ-KIIIA shows that the key residues important for activity against NaV1.2 and NaV1.4, as identified recently by Zhang et al. (11), all reside on the α-helical region of the peptide, with the exception of Arg14. This was also the case for μ-SIIIA, suggesting an important role for the α-helix in presenting these residues to mammalian sodium channels (41). Our results for μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] also demonstrate that the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide bond can be removed without significantly distorting the α-helix and with minimal change in the activity of the peptide against the NaV1.2 subtype and only slight reductions in affinity for the NaV1.4 and NaV1.7 subtypes, in spite of the apparent flexibility of the N-terminal imparted by removal of the disulfide bond. As the disulfide-deficient analogue maintains activity similar to the native toxin, this suggests that the conformation of the N-terminal region is not critical in maintaining the structure and activity of the peptide against the NaV1.2 subtype. However, this flexibility may influence the selectivity profile of the toxin for other NaV subtypes, such as NaV1.4 and NaV1.7. Interestingly, μ-SIIIA, which has a longer N-terminal loop, reportedly does not target the NaV1.1 and NaV1.7 subtypes (41).

Although there was minimal change in the activity against NaV1.2 and NaV1.4 upon removal of the Cys1-Cys9 disulfide bridge, the disulfide deletion increased both kon and koff of the peptide against these subtypes. Interestingly, disulfide deletion also increased the kinetics of peptide binding to its target channel in the case of conkunitzin-S1 (43), a neurotoxin that binds voltage-gated potassium channels. In that study, addition of a disulfide bond to the native toxin decreased both kon and koff for binding of the toxin to the Shaker potassium channel target, but did not affect the overall blocking activity against this channel. These results suggest that the enhanced flexibility of a peptide toxin conferred by removing a conformational restraint such as a disulfide bridge may enhance its ability to both associate with and dissociate from its target channel. It is also possible that the slightly more expanded and flexible N-terminal region of μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] compared with μ-KIIIA may enable it to sample a larger volume of conformational space and thereby facilitate eventual binding to the channel.

The relationship between conformational flexibility and binding is supported by the MD simulations - removal of the Cys1-Cys9 and Cys2-Cys15 disulfide bridges resulted in analogues that were more conformationally flexible than the native toxin but still retained activity against the VGSCs, albeit with lower affinity (17). In the MD simulations of μ-KIIIA[C4A,C16A] removal of the Cys4-Cys16 disulfide restraint resulted in a change of conformation, consistent with its inability to bind VGSCs. Thus, the simulations have provided possible explanations for the varying importance of individual disulfide bonds in relation to the activity of μ-KIIIA on VGSCs. The structures from the MD simulations show exceptional similarity with the ensemble of experimentally derived NMR structures for both μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIA[C1A,C9A]. The high level of conformity between the experimental and theoretical structures confirms the utility of MD in the structural analysis of these small peptides.

Accumulating structural and functional studies, including this work, on the three μ-conotoxins, μ-SmIIIA, μ-SIIIA and μ-KIIIA, provide us with an emerging picture of structural requirements of these peptides as blockers of VGSCs. An important conclusion is that the number of residues in the first loop has no significant effect on the overall conformations of the second and third loops that present critical residues. The second is that the μ-conotoxin scaffold can accommodate backbone spacers and/or removal of individual disulfide bridges without compromising bioactivity, emphasizing the adaptability of the μ-conotoxin scaffold and making it a valuable template for peptide engineering. Our results therefore have important implications for the future design of minimized analogues with greater subtype selectivity for use in the treatment of pain (11). It seems that the N-terminal region could be truncated to produce a minimized analogue which retains the key residues on the α-helical scaffold (-XXKWXRDHXR-). The success of MD simulations in reproducing the structures of μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A], as documented in Figure 5, implies that this approach will be a valuable adjunct to the process of designing truncated and stabilized analogues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Jean Rivier for providing the synthetic peptides and Professor Alan Goldin for providing clones for rNaV1.2 through 1.5 and mNaV1.6, Prof. Gail Mandel for the rNaV1.7 clone, and Dr. Layla Azam for cRNA preparations from these clones.

Abbreviations

- μ-GIIIA, μ-GIIIB

μ-conotoxins GIIIA and GIIIB, respectively, from Conus geographus

- μ-KIIIA

μ-conotoxin KIIIA from C. kinoshitai

- μ-KIIIA[C1A

C9A], μ-KIIIA with Cys1 and 9 replaced by Ala

- NaV1.1

NaV1.2, etc., the α-subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel subtype 1.1, 1.2, etc. cloned from rat (when abbreviation is preceded by an “r”) or mouse (when abbreviation is preceded by an “m”)

- μ-PIIIA

μ-conotoxin PIIIA from C. purpurascens

- μ-SIIIA

μ-conotoxin SIIIA from C. striatus

- μ-SmIIIA

μ-conotoxin SmIIIA from C. stercusmuscarum

- MD

molecular dynamics

- RMS

root mean square

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants GM 48677 (to G.B., B.M.O. and D.Y.) and R21 NS055845 (to G.B. and D.Y.), as well as an NHMRC IRIISS grant 361646 and a Victorian State Government OIS grant. R.S.N. acknowledges fellowship support from the NHMRC.

Chemical shift assignments and the families of structures for μ-KIIIA and μ-KIIIA[C1A,C9A] have been deposited in the BioMagResBank with accession numbers 20048 and 20049, respectively.

Two tables of chemical shifts (KIIIA and KIIIA[C1A,C9A]) and eight figures (two figures of NMR spectra of KIIIA and KIIIA[C1A,C9A], four figures summarizing and comparing NOEs, angular parameters and chemical shift data, and two figures of results of MD simulations). This material can be accessed free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.French RJ, Terlau H. Sodium channel toxins--receptor targeting and therapeutic potential. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:3053–3064. doi: 10.2174/0929867043363866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummins TR, Sheets PL, Waxman SG. The roles of sodium channels in nociception: Implications for mechanisms of pain. Pain. 2007;131:243–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Cestele S, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, Scheuer T. Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon. 2007;49:124–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulaj G, Zhang MM, Green BR, Fiedler B, Layer RT, Wei S, Nielsen JS, Low SJ, Klein BD, Wagstaff JD, Chicoine L, Harty TP, Terlau H, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM. Synthetic μO-conotoxin MrVIB blocks TTX-resistant sodium channel NaV1.8 and has a long-lasting analgesic activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7404–7414. doi: 10.1021/bi060159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leipold E, DeBie H, Zorn S, Borges A, Olivera BM, Terlau H, Heinemann SH. μO conotoxins inhibit NaV channels by interfering with their voltage sensors in domain-2. Channels. 2007;1:253–262. doi: 10.4161/chan.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmalhofer W, Calhoun J, Burrows R, Bailey T, Kohler MG, Weinglass AB, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML, Koltzenburg M, Priest BT. ProTx-II, a selective inhibitor of NaV1.7 sodium channels, blocks action potential propagation in nociceptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1476–1484. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokolov S, Kraus RL, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Inhibition of sodium channel gating by trapping the domain II voltage sensor with protoxin II. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1020–1028. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norton RS, Olivera BM. Conotoxins down under. Toxicon. 2006;48:780–798. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han TS, Teichert RW, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Conus venoms - a rich source of peptide-based therapeutics. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2462–2479. doi: 10.2174/138161208785777469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulaj G, West PJ, Garrett JE, Watkins M, Zhang MM, Norton RS, Smith BJ, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM. Novel conotoxins from Conus striatus and Conus kinoshitai selectively block TTX-resistant sodium channels. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7259–7265. doi: 10.1021/bi0473408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang MM, Green BR, Catlin P, Fiedler B, Azam L, Chadwick A, Terlau H, McArthur JR, French RJ, Gulyas J, Rivier JE, Smith BJ, Norton RS, Olivera BM, Yoshikami D, Bulaj G. Structure/function characterization of μ-conotoxin KIIIA, an analgesic, nearly irreversible blocker of mammalian neuronal sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30699–30706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green BR, Catlin P, Zhang MM, Fiedler B, Bayudan W, Morrison A, Norton RS, Smith BJ, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Conotoxins containing nonnatural backbone spacers: cladistic-based design, chemical synthesis, and improved analgesic activity. Chem Biol. 2007;14:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrega L, Mosbah A, Ferrat G, Beeton C, Andreotti N, Mansuelle P, Darbon H, De Waard M, Sabatier JM. The impact of the fourth disulfide bridge in scorpion toxins of the α-KTx6 subfamily. Proteins. 2005;61:1010–1023. doi: 10.1002/prot.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnham KJ, Torres AM, Alewood D, Alewood PF, Domagala T, Nice EC, Norton RS. Role of the 6–20 disulfide bridge in the structure and activity of epidermal growth factor. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1738–1749. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flinn JP, Pallaghy PK, Lew MJ, Murphy R, Angus JA, Norton RS. Role of disulfide bridges in the folding, structure and biological activity of ω-conotoxin GVIA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1434:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennington MW, Lanigan MD, Kalman K, Mahnir VM, Rauer H, McVaugh CT, Behm D, Donaldson D, Chandy KG, Kem WR, Norton RS. Role of disulfide bonds in the structure and potassium channel blocking activity of ShK toxin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14549–14558. doi: 10.1021/bi991282m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han TS, Zhang MM, Walewska A, Gruszczynski P, Cheatham TE, III, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Structurally-minimized disulfidedeficient μ-conotoxin analogs as sodium channel blockers: implications for designing conopeptide-based therapeutics. Chem Med Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800292. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer AG, Cavanagh J, Wright PE, Rance M. Sensitivity improvement in proton-detected 2-dimensional heteronuclear correlation NMRspectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1991;93:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay LE, Keifer P, Saarinen T. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbs SJ, Johnson CS. A PFG-NMR experiment for accurate diffusion and flow studies in the presence of eddy currents. J Magn Reson. 1991;93:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dingley AJ, Mackay JP, Chapman BE, Morris MB, Kuchel PW, Hambly BD, King GF. Measuring protein self-association using pulsed-field-gradient NMR spectroscopy: application to myosin light chain 2. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00197813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao S, Howlett GJ, Norton RS. Peptide self-association in aqueous trifluoroethanol monitored by pulsed field gradient NMR diffusion measurements. J Biomol NMR. 2000;16:109–119. doi: 10.1023/a:1008382624724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piotto M, Saudek V, Sklenar V. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J Biomol NMR. 1992;2:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartels C, Xia TH, Billeter M, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral-analysis of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00417486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seavey BR, Farr EA, Westler WM, Markley JL. A relational database for sequence-specific protein NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1991;1:217–236. doi: 10.1007/BF01875516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann T, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE-identification in the NOESY spectra using the new software ATNOS. J Biomol NMR. 2002;24:171–189. doi: 10.1023/a:1021614115432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–55. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keizer DW, West PJ, Lee EF, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM, Bulaj G, Norton RS. Structural basis for tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel binding by μ-conotoxin SmIIIA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46805–46813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindahl E, Hess B, van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: A package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J Mol Model. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. The OPLS potential functions for proteins. Energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1657–1666. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem. 1977;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daura X, Gademann K, Juan B, Seebach D, van Gunsteren WF, Mark AE. Peptide folding: When simulation meets experiment. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 37.West PJ, Bulaj G, Garrett JE, Olivera BM, Yoshikami D. μ-conotoxin SmIIIA, a potent inhibitor of tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels in amphibian sympathetic and sensory neurons. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15388–15393. doi: 10.1021/bi0265628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellison M, Feng ZP, Park AJ, Zhang X, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM, Norton RS. α-RgIA, a novel conotoxin that blocks the α9α10 nAChR: structure and identification of key receptor-binding residues. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:1216–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merutka G, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. ‘Random coil’ 1H chemical shifts obtained as a function of temperature and trifluoroethanol concentration for the peptide series GGXGG. J Biomol NMR. 1995;5:14–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00227466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M-M, McArthur JR, Azam L, Bulaj G, Olivera BM, French RJ, Yoshikami D. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions between tetrodotoxin and μ-conotoxin in blocking voltage-gated sodium channels. Channels. 2009 doi: 10.4161/chan.3.1.7500. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder CI, Ekberg J, Nielsen KJ, Adams D, Loughnan ML, Thomas L, Adams DJ, Alewood PF, Lewis RJ. Neuronally selective μ-conotoxins from Conus striatus utilize an α-helical motif to target mammalian sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21621–21628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao S, Zhang MM, Yoshikami D, Azam L, Olivera BM, Bulaj G, Norton RS. Structure, dynamics and selectivity of the sodium channel blocker μ-conotoxin SIIIA. Biochemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1021/bi801010u. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayrhuber M, Vijayan V, Ferber M, Graf R, Korukottu J, Imperial J, Garrett JE, Olivera BM, Terlau H, Zweckstetter M, Becker S. Conkunitzin-S1 is the first member of a new Kunitz-type neurotoxin family. Structural and functional characterization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23766–23770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang CZ, Zhang H, Jiang H, Lu W, Zhao ZQ, Chi CW. A novel conotoxin from Conus striatus, μ-SIIIA, selectively blocking rat tetrodotoxinresistant sodium channels. Toxicon. 2006;47:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang MM, Fiedler B, Green BR, Catlin P, Watkins M, Garrett JE, Smith BJ, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Structural and functional diversities among μ-conotoxins targeting TTX-resistant sodium channels. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3723–3732. doi: 10.1021/bi052162j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Holm A, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J Biomol NMR. 1995;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.