Abstract

Background

African American women have disproportionately higher rates of breast cancer (BC) mortality than all other ethnic groups, thus highlighting the importance of promoting early detection.

Methods

African American women (N = 984) from San Diego, California participated in a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of BC education sessions offered in beauty salons. Cosmetologists received ongoing support, training, and additional culturally aligned educational materials to help them engage their clients in dialogues about the importance of BC early detection. Posters and literature about BC early detection were displayed throughout the salons and cosmetologists used synthetic breast models to show their clients how BC lumps might feel. Participants in the control group received a comparable diabetes education program. Baseline and six month follow-up surveys were administered to evaluate changes in women’s BC knowledge, attitudes and screening behaviors.

Results

This intervention was well received by the participants and their cosmetologists and did not interfere with, or prolong, the client’s salon visit. Women in the intervention group reported significantly higher rates of mammography compared to women in the control group. Training a single educator proved sufficient to permeate the entire salon with the health message and salon clients agreed that cosmetologists could become effective health educators.

Conclusions

Cosmetologists are in an ideal position to increase African American women’s BC knowledge and adherence to BC screening guidelines.

MeSH: African American, Breast cancer, Early detection, Education, Screening

INTRODUCTION

Among African American women, breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly occurring cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death.1 Although the BC incidence is about 13% lower in African American women than in White women, African American women are more likely to die of their disease. The five-year relative survival rate for African American women is 77%, compared to 90% for Caucasian women.2

Clinical differences have been identified that can account for some of the survival difference between African American and Caucasian women, e.g., negative estrogen receptor status3, tumor size and stage at diagnosis,3 lifestyle-linked characteristics, such as obesity,4 and neutropenia.5, 6 There is growing evidence that genetic factors may also affect the incidence and/or aggressiveness of BC in African American women.7–10 Socioeconomic factors have also been shown to play a role in creating this disparity, e.g., lack of insurance coverage,11, 12 reduced access to screening13 and treatment,14–16 and treatment differences.15, 17, 18

Early detection and prompt treatment have been demonstrated to reduce BC mortality and the extent of needed treatment.2 Under-utilization and irregular utilization of BC screening exams among African American women are believed to contribute to the disparities in mortality rates.19–21 This reduced adherence to breast cancer screening guidelines leads to later stage cancer diagnoses in African American women, a factor correlated with lower survival rates.2, 22 Treatment delays of even three months can contribute to BC mortality.23 While only 64% of African American women aged 40 and over report adherence to recommendations for annual clinical breast examination (CBE),24 even fewer (50%) reported adhering to the most effective early detection strategy, having a mammogram in the past year.25–31

Lack of knowledge about BC has been shown to be a contributing factor to low adherence to recommended BC screening guidelines.23, 28–30 Educational interventions aimed at African American women regarding BC early detection have proven successful in increasing their proficiency of breast self-examination and raising the importance of BC screening.5 In spite of such education efforts, however, African American women’s BC screening rates still lag behind those of women in other communities. To reach a broader cross-section of African American women, additional outreach strategies are needed.

The primary objective of this study was to create a BC education program which increased the odds of African American women adhering to recommended breast cancer screening guidelines. To increase the odds of creating a successful intervention, the program was grounded on the five constructs of the Health Belief Model: susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and cues to action. While the first four constructs could be readily incorporated into a training program, the challenge was finding a public venue where women could be repeatedly cued to screening action. Offering the intervention at beauty salons serving a predominantly African American clientele was hypothesized to be an ideal venue for cueing women to screening.

METHODS

Participants

The intervention required consent from two groups of participants: cosmetologists and their clients. Eligibility criteria for the cosmetologists included being female, at least 18 years old, English language proficient, and possession of a current California cosmetology license. Stylists were paid $50 per month for their involvement in their own training to become a community breast cancer educator, involvement with participant recruitment and accrual, and delivery of the training components of the program.

Eligibility criteria for their clients included being self-identified African American women over the age of 20 who were receiving services at a participating salon with any of the salons’ cosmetologists. This broad age range was chosen because while mammograms are not recommended for younger women, they still need to know that they should have a clinical breast exam every three years. In addition, they could help disseminate the mammography and CBE screening recommendations to age-eligible women in their families and social circles.

Evolution of the BC Training Program

This health promotion intervention had originally begun as a church-based community-campus research partnership between the Outreach Program of the Moores UCSD Cancer Center and the Presbytery of San Diego and Imperial Counties.32 Following that study, the African American church leaders and lay church women leaders observed that repeated church-based programs about BC were reaching the same attendees. They felt that new strategies were needed if the community was to achieve the dramatic BC screening goals set by the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society.

Based on their past experiences working with the university PI in a community-campus partnership, the churchwomen asked for suggestions about other strategies that could be used for closing the known cancer disparities gaps experienced by the African American community. They liked the idea of a salon-based BC education program because the cosmetologists were trusted members of the community and were required to complete course work in health as part of their licensing requirements.

The church women also liked the fact that a salon-based BC education program would be seen as emanating from within the community, rather than as a university imposed program. Equally important, they recognized that with a salon-based information dissemination strategy, the messages would continue to be delivered well beyond the end of the program. The cosmetologists would remain in their neighborhoods, where they could continue disseminating the BC information.

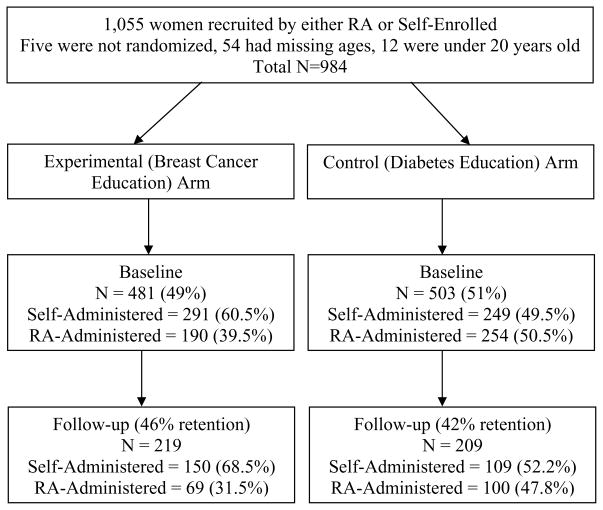

The church women gave this strategy their full support, from recruiting the stylists to serving as a sounding board for the PI. The PI’s role was to secure the funding needed to implement the program, create a plan for scientifically testing the program, and lead the scientific evaluation of the program’s impact. Strategizing together, the partnership devised a new methodology that ultimately became The Black Cosmetologists Promoting Health Program.31, 33 Church leaders personally invited civic-minded cosmetologists whom they knew, to consider involving their salons in the testing of a new health promotion training program. The principal investigator (PI) then met individually with each referred cosmetologists at 24 salons to explain the structure of the planned randomized controlled education trial. Twenty of the 24 stylists consented to participate in the study and agreed to help recruit their clients to join the study (Figure 1). Next, the salons' clients were actively recruited to the study by an undergraduate African American research assistant (RA) or passively recruited by salon exhibits offering self-administered consent documents and baseline surveys. The RAs and participating cosmetologists were taught Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved recruitment strategies to encourage their clients to participate. They were taught how to consent and assist their clients in completing the baseline survey. The relevant IRB compliance issues related to the delivery of the educational intervention was also highlighted in their training.

Figure 1.

Participant Retention within the Randomized Control Education Trial

As part of the consenting process, women were told verbally and in writing that they were being invited to join a study that was evaluating the effectiveness of a health education program being offered in beauty salons. They were told the study would last up to two years, that a cosmetologist in the salon would be given information about a specific disease to share with the salon’s clients, and that the clients would be asked to complete two to three brief surveys during the study to help evaluate the program. Clients were told that those who enrolled in the study would be entered in the salon’s raffle for the large, attractive basket of beauty supplies displayed next to the study’s recruitment materials. These methods are detailed in earlier papers.28, 30, 33

Blinding or Masking

Six-months after the start of the intervention program, a new group of RAs administered the follow-up post-intervention phone surveys. They were blind to the participants’ study arm assignment. The RAs attempted to contact the participant at least ten times by phone, calling at different times and on different days to increase the chances of reaching the participants. When the RAs were unsuccessful in reaching a woman after ten phone attempts, the survey and a self-addressed, stamped envelope was mailed to the address the participant had provided on her baseline survey. If that was not returned, the RAs asked the stylists if they could facilitate contact with the participants. Sometimes, the cosmetologists were able to act as a point of contact between the study and the participant. Other times, the cosmetologists confirmed that they had not seen the participant. This was not unusual in a town with two major military bases (Naval and Marine) from which troops and service personnel and their family members were often deployed or assigned to a different base.

Breast cancer educational intervention

For the breast cancer intervention, the cosmetologists were asked to proactively engage their clients in discussions anticipated to encourage them and their circle of family and friends to adhere to recommended breast cancer screening guidelines. They were also to try to engage the salons’ other stylists and their clients in participating in these discussions. Once the salon’s cohort of participants was recruited, consented, and the baseline surveys completed, the cosmetologists received approximately four hours of one-on-one training with the PI and an additional four hours of reading materials that reviewed and summarized the PI’s training. The reading materials came from such respected resources as the National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Cancer Society (ACS), and Susan G. Komen-for-the-Cure Foundation.

The cosmetologists also received individual training from an African American ancestral storyteller to enhance their ability to pass along their health promotion messages orally. Ancestral storytelling is considered an integral element of African culture and trusted way of spreading information among family and friends, through the generations. This was anticipated to help the cosmetologists deliver their messages to clients in a manner that would facilitate their clients passing the messages along to others.34 Gladwell saw this training in storytelling as one of the components that increased the “stickiness” of the messages the cosmetologists were delivering.35

Every two weeks, the cosmetologists were given hands-on training materials and shown ways the materials could be used to facilitate discussions with their clients to keep the BC screening message laced with fresh information. For example, a series of eight laminated “Mirror Challenges” were sequentially posted in a corner of the cosmetologists’ mirror. An example of a challenge is, “Ask me about myth #4: There’s no breast cancer in my family, so I don’t have to worry.” The other side of the mirror challenge contained a short paragraph that offered clarifying information about the statement.

Relevant articles from lay newspapers and magazines trusted by the African American community (NY and LA Times, Essence, Ebony and Ivory) were also given to the cosmetologists. These articles covered special interest stories, such as Black celebrities with cancer, as well as information on breast cancer rates. The articles were enlarged so they could be read without reading glasses, and key points were highlighted. The articles were laminated so the cosmetologists could repeatedly hand them to their salon clients without having become tattered. This gave the cosmetologists a steady stream of new triggers for initiating focused discussions. This formatting of the articles also avoided the situation where a brochure is given to a client who promptly tucks it in a pocket with the promise to “read it later.” In addition, the cosmetologists also used a three-ring binder of information with their clients as they were receiving services.. The binder format made it possible to insert new information for discussion, giving the cosmetologists new reasons to share the binder with their regular clients. Previously used mirror challenges were also added to the binder.

Cosmetologists in the BC training arm were given a soft plastic BC model to show women how a BC lump felt and a string of clay beads that depicted the various sizes of palpable BC lumps. Both learning aids were used to drive home the key point that mammograms could find BC before the lumps could even be felt. There were also BC posters on the salon and restroom walls and brochures in plexiglass stands throughout the salons, all of which presented images of African American women. Thus from the minute the clients arrived at the salon, there were messages about BC that were clearly intended for the benefit of African American women.

The cosmetologists’ were told that their primary goal was to convey to their clients the importance of early breast cancer detection and prompt treatment in reducing BC morbidity and mortality rates, and the role that adherence to CBE and mammography guidelines play in promoting early detection. They were told to customize their messages based upon their knowledge of how best to approach each of their clients. There was no attempt to deliver a specified “dose” of information to each client, nor was this possible. Some women had weekly appointments, while for others six, eight, or more weeks could elapse between visits, underscoring the importance of delivering any important health message via beauty salons over multiple months.

The PI made brief, unannounced visits to each stylist about every two weeks during the first three months of the study, and then at least monthly thereafter. The visits were a time to neaten and replenish each salon’s publically displayed messages, deliver new materials to the cosmetologists, offer a brief refresher session and training on the new materials, and answer any questions that might have arisen since the previous visit. These visits were an opportunity to assure that the program’s educational materials were comparably displayed in all the salons. The cosmetologists had round-the-clock access to the PI, thus providing assurance that they would never be in situations with their clients that they felt were beyond their time or ability to handle. The cosmetologists were compensated $50 a month throughout the program in recognition that the PI and staff would cause interruptions in their work schedule for the training and data collection aspects of the study.

The control arm participants participated in an equivalent training program about diabetes. It was identical in all ways, but content.

Hypothesis

The authors hypothesized that women in the BC intervention arm (experimental) would report a higher rate of mammography adherence compared to the women in the diabetes intervention arm (control).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was adherence to mammography screening guidelines since mammograms can detect 85% of BC and are the most effective method of early detection. At baseline, women were asked to self-report the date of their last mammogram and those 40 and older were considered adherent for mammograms done in the past year.

Secondary outcomes included adherence to recommendations for CBE, as well as participants’ awareness and perceptions of their vulnerability for breast cancer. Participants 40 and older were considered adherent for CBEs done in the past year.

Following the constructs of the Health Belief Model, the baseline and follow-up surveys assessed each woman’s awareness of BC as a serious health threat, her personal exposure to the disease, her sense of personal vulnerability, the steps she might take to reduce her personal risk of dying from breast cancer, and her current adherence to recommended screening guidelines. Survey questions asked, for example, “What do you think are the most serious health problems facing Black women?” They had spaces for listing up to four health problems.

Survey instruments had been developed in reference to the specific content area of the BC and diabetes education programs that were offered in the two study arms. Prior to using the instruments in this study, these one-item assessments on screening behaviors and awareness of serious health problems were found to be acceptable to participants in the pilot study.31, 33

Randomization by Cluster

Two issues prompted the use of a study design in which salons were treated as the unit of randomization.36 First, it would be impossible to avoid contamination between the two groups of study participants if women were randomized within the same salon. Communications between cosmetologists and clients were public, making it impossible to prevent a woman randomized to one arm from hearing a discussion between cosmetologist and a client randomized to the other arm. Further, the cosmetologists’ verbally delivered health messages were reinforced by posters, pamphlets, and booklets placed strategically throughout the salon. This message dissemination strategy was chosen so that even women who were clients of the salon’s other stylists could be repeatedly cued to that salon’s health promotion message. The pilot study had also confirmed that African American women seek their services at a single salon, reducing the risk of message contamination that could occur if clients were receiving services at different salons that were participating in different study arms.

Participating clients from each salon were recruited and surveyed before the salons were randomized to avoid the possibility that the cosmetologists or the RA might unintentionally introduce bias during participant recruitment. Working in the salons on a variety of days and at various times, the RA sequentially invited clients to join the study. This assured methodological consistency among the salons and gave a reliable estimate of the refusal rate of 13% (71 of 530 women who were directly invited to join the study by the RA). The 71 women who declined to participate all agreed to complete an anonymous, four-question survey, when asked by the RA, to permit sociodemographic comparisons between participants and non-participants.

As the full complement of participants from each salon was achieved, salons were randomly assigned to either the BC or diabetes arm. A computer-generated paired randomization table was followed to assure an equal numbers of salons in each arm at the end of the recruitment phase.

Sample size

Previously published studies indicated that 25% of the subjects would have had a screening mammogram at baseline.23, 37 In the sample size calculations, an increase in follow-up mammography rate to 40% in the experimental arm and type I error of .05 was assumed. There were no estimates of intra-cluster correlation, but it was expected to be small, so 0.01 was used in the sample size calculations. With approximately 20 people within each cluster (salon) and 20 clusters, the power to detect an increase in follow-up mammograms to 40% is 85%.

The literature is replete with reports related to the difficulty of retaining research participants over extended periods of time.38–43 In recognition that this retention challenge would be exacerbated by the attrition anticipated from the region’s large military population and deployment patterns, a baseline sample of at least 1,000 women was recommended by the Center’s consulting statistician to accommodate a study attrition rate that was anticipated to be as great as 70%. In addition, the use of salons as the unit of randomization prompted the use of smaller numbers of women from more salons, in case the preliminary analysis required the data to be analyzed by the 20 participating salons.

As a recruitment goal, the RA recruited at least 30 women per salon for the salons with three or more cosmetologists and recruited at least 15 women per salon for the smaller salons. The self-administered recruitment goals were the same as the RA’s goals for the respective salon sizes.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics of subjects and retention rates in the two treatment groups were compared using Chi-square tests. Baseline rates of each screening method were also compared with an adjustment for age with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test. Hierarchical logistic regression models were used to test the differences between baseline and six month follow-up levels of knowledge, BC screening behaviors, and BC awareness for the BC and diabetes intervention groups. SAS version 9.2, proc glimmix was used to conduct all analyses and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The salon identifier was included in the model as a random effect and the intervention group was a fixed effect at the salon level. Age and education were considered as explanatory effects at the subject level and were only retained in the model if they were significant at level α=.10.

The significant differences between those who completed the follow-up versus those who did not posed a threat to internal validity due to mortality or systematic drop-out bias. Two separate analyses were conducted: an intent-to-treat analysis with the full sample (N=984) and subgroup analysis of those who completed both baseline and follow-up (completers) (N=428). If the participant did not complete the follow-up assessment, their responses at baseline were imputed at follow-up (i.e., those who reported not being compliant with screening guidelines at baseline were assumed to also not have become compliant by the follow-up) and this was considered an intent-to-treat analyses. Separate analyses of the subgroup of participants who completed both baseline and follow-up were also conducted.

Results

Sample Description

All participants (N = 1,055) were self-identified African American women living within San Diego County’s 5,000 square miles. Of these women, five were dropped from the study because their cosmetologist decided to conduct her business in her home shortly after joining the study, a condition that made her ineligible to participate in the salon-based study. Of the remaining 1050 women, 54 had missing data on their ages. Twelve women were between the ages of 18 and 20 years old. Since screening recommendations begin at age 20, these younger women were excluded from the analysis. Sociodemographic and recruitment information for the remaining 984 women are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and Recruitment Method Information (Total Sample = 984 women)

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Breast Cancer N = 481 % (N) | Diabetes N = 503 % (N) | Total N = 984 % (N) | Breast Cancer N = 219 % (N) | Diabetes N = 209 % (N) | Total N = 428 % (N) | |

|

| ||||||

| Age range | 20–81 | 20–88 | 20–88 | 21–88 | 20–81 | 20–88 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 40.5 (13) | 40.8 (14) | 40.6 (13) | 41.8 (13) | 43.2 (14) | 42.5 (14) |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| < to high school | 11 (57) | 11 (58) | 12 (115) | 9 (19) | 11 (24) | 10 (43) |

| Some college | 53 (256) | 51 (258) | 52 (514) | 49 (107) | 54 (112) | 51 (220) |

| Completed college | 32 (155) | 35 (177) | 34 (332) | 40 (87) | 33 (70) | 37 (157) |

| Missing value | 3 (13) | 2 (10) | 3 (23) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (9) |

|

| ||||||

| Work outside home | 79 (378) | 99 (386) | 78 (764) | 79 (173) | 99 (161) | 77 (332) |

|

| ||||||

| Hx of breast cancer | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 1 (12) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (6) |

|

| ||||||

| Recruitment | ||||||

| Display method | 61 (291) | 49 (249) | 55 (540) | 68 (150) | 52 (109) | 61 (260) |

| RA method | 39 (190) | 51 (254) | 45 (444) | 32 (69) | 48 (100) | 39 (169) |

|

| ||||||

| Same cosmetologist | 17 (82) | 36 (183) | 27 (265) | 59 (27) | 27 (56) | 27 (115) |

Of the 984 women, 428 (43%) completed both the baseline and the six month follow-up surveys: 219 women in the breast cancer intervention (intervention) and 209 in the diabetes (control) group. Of the total number of women who participated in the baseline survey, there was a 46% retention rate for those in the breast cancer group and a 42% retention rate for those in the diabetes group. The retention rates between the two groups at follow-up were not significantly different (χ2 = 1.4, p>0.05, Figure 1). There were no differences in age, CBE, and mammography use at baseline between the two groups. There were no differences in mammography screening utilization rates by size of salon at baseline.

Given the 57% attrition rate, an analysis was also done to determine whether the women who were retained in the study groups were significantly different from the women recruited at baseline. A significantly higher percentage of women who completed the follow-up survey did so through the display method (61%) rather than through RA recruitment (39%, χ2 = 9.7, p<.05). There were no significant differences in age, education level, or any of the baseline measures used to assess outcomes (CBE, and mammography use).

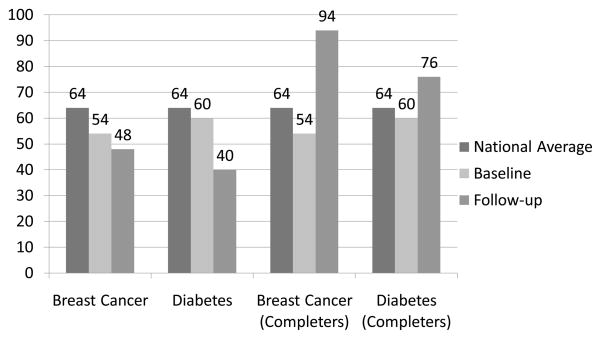

Impact of the Intervention

Figures 2 and 3 show the results of the intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses for the entire sample and the analyses for the participants who completed both Time 1 and Time 2 (completers). At baseline, there were no significant differences in reported adherence to mammography and CBE. As anticipated given the high attrition rate by follow-up, the ITT analysis did not produce evidence of significant differences between groups at follow-up. However, the ITT analysis showed similar trends to the completers analysis, which showed that women in both treatment arms reported significantly (p<.05) higher rates of mammography at follow-up compared to baseline.

Figure 2.

Mammogram rates (%) at baseline and follow-up for women 40 years and older for intent-to-treat (N=467) and Completers (N=232)

Note: National averages are based on mammography rates within the past year for 2009–2010 data for Black, Non-Hispanic women over 40 years of age.40

Figure 3.

CBE Rates (%) at baseline and follow-up for women 40 years and older for entire sample (N=467) and Completers (N=232)

Note: National averages are based 2007–2008 data on Black, Non-Hispanic women over 40 years of age.41

In the model that predicted mammography screening, age was a significant covariate, with higher rates of mammography in women 40+, as should have occurred based on screening guidelines. Therefore, the effect of the intervention on mammography adherence was considered in the subgroup of women 40+ only since the intervention was targeted to promoting screening change in this group. As hypothesized, the odds ratio of reporting newly adherent mammography screening among women 40+ in the BC intervention group was 2.0 (95% CI 1.03 – 3.85) times higher than women in the diabetes control group. Table 2 shows the changes in mammography screening from baseline to follow-up among women 40+ years of age.

Table 2.

Changes in Mammography Screening from Baseline to Follow-up (40+ years, Completers, N = 232)

| Breast cancer N = 112 % (N) | Diabetes N =120% (N) | |

|---|---|---|

| No change or change for worse | 54 (60) | 70 (84) |

| Change in positive direction (mammogram reported at follow-up but not at baseline) | 46 (52) | 30 (36) |

Significantly different, F1,18= 6.6, p<.01

Two questions were used to evaluate women’s attitudes toward breast cancer: the perceived adequacy of their BC knowledge and their perceptions of whether BC posed a serious health threat to Black women. For the first question, there were no significant differences at either baseline or at the six-month follow-up between women’s perceptions of the adequacy of their breast cancer knowledge regardless of their intervention group for either the ITT or completers analyses. Given that there were no differences at baseline, baseline scores were not controlled for in the between group comparison at follow-up.

Differences were noted in participants’ perceptions of the seriousness of BC as a health threat in the ITT analysis, where both arms’ participants’ top-of-mind awareness of BC as a serious health threat dropped, but did so significantly more in the diabetes arm. At baseline and follow-up, participants were asked the open-ended question, “What do you think are the most serious health problems facing Black women?” to solicit their perceptions of the most top-of-mind problems. They were given space sufficient to list up to four responses. In addition to breast cancer, women listed diabetes, cerebrovascular and heart disease, HIV, and obesity as the most serious health problems. These data are discussed in an earlier paper.28 At baseline, women in both arms listed BC with the same frequency among their four responses. At follow-up, significantly (p< .05) fewer women in both intervention groups listed BC as a serious health problem, but women in the BC intervention group listed BC significantly (p<.05) more frequently than women in the diabetes intervention group (odds of listing BC were 1.8 times as high in the BC intervention group; 95% CI 1.0–3.1).

When participants responded to the question about what is the most serious health threat to Black women, the problem with the greatest top-of-mind concern would presumably be placed in the first response line. When only the first response line was compared, at baseline there were no significant differences in the rate with which BC was listed in first place between the two intervention groups, and this did not change at follow-up for either the ITT or completers analyses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Awareness of Breast Cancer as a Serious Health Problem and Top of Mind Awareness of Breast Cancer (Completers, N=428)

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Cancer N = 219 % (N) | Diabetes N = 209 % (N) | Total N = 428 % (N) | Cancer N = 219 % (N) | Diabetes N = 209 % (N) | Total N = 428% (N) | |

|

| ||||||

| Breast Cancer as Serious Health Problem | * | * | * | |||

| Yes | 56 (122) | 49 (103) | 53 (225) | 46 (100) | 33 (69) | 61 (169) |

| No | 44 (97) | 51 (106) | 47 (203) | 54 (119) | 67 (140) | 39 (259) |

|

| ||||||

| Top of Mind Awareness of Breast Cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (59) | 25 (53) | 26 (112) | 26 (57) | 22 (46) | 11 (48) |

| No | 72 (157) | 72 (150) | 72 (307) | 68 (148) | 53 (111) | 61 (259) |

Significantly different at follow-up, F1,18= 7.2, p< .05

Programmatic Findings

At follow-up, when the participants were asked if health promotion information had been displayed in their salon, 57% (244/428) of the women reported that health education materials were displayed in their salon, and 16% (68/428) said that no health promotion materials were displayed. Program participants were also asked at follow-up whether they thought cosmetologists could effectively pass along health information to their clients and 80% of the women (343/428) felt they could. No differences were noted for any of these questions by either randomization arm or by participants’ age. Participants were also asked whether a health education program had been offered in their salon over the past six months. Overall, 242 (57%) participants reported that the cosmetologists in their salon were offering health information to their clients, while 25% (109/428) said that they were not aware of a health promotion program. The rest did not know or did not respond to this question. When the 428 participants were categorized by whether their cosmetologist was one of those who had received training and charged with disseminating their information, no significant differences appeared, suggesting that the trained educator-cosmetologists had effectively permeated the entire salon’s stylists and clients with her messages.

Discussion

The Health Belief Model is a theoretical framework that has been widely used in the creation of health education programs. Within this framework, the ultimate goal of a health education training program is to increase knowledge and self-efficacy and to change attitudes and beliefs anticipated to increase the number of people who will adopt optimal health-promoting (or disease-preventing) behaviors.44–46

The randomized controlled trial described in this paper was done to evaluate the efficacy of a beauty salon-based education program to promote greater adherence to BC screening guidelines among African American women. Following the first six months of the program’s operation, participants in the BC intervention group engaged in mammography screening with a significantly greater frequency than the women in the control group who had received information about diabetes during the same six month time frame. Consistent with the Health Belief Model, women in the breast cancer intervention showed a shift in behaviors that would be viewed as conducive to the observed increased uptake in BC screening.

It is interesting to note that fewer women viewed BC as a major health problem at the follow-up assessment. Further study is warranted to determine if this shift might reflect a positive outcome. For example, the third construct of the Health Belief Model is getting people to believe that the recommended behavior will be effective in reducing the health threat. The fourth construct is lowering the perceived barriers to, or perceived negative outcomes of, the recommended health action. Thus, it might be hypothesized that, the knowledge gained through the BC intervention may have led women to now view BC as a disease they had a better chance to control with early detection. Further, with the information that they could access free BC screening and treatment, the perceived barriers to accessing the recommended screening behaviors may have diminished. Thus this constellation of new knowledge may have coalesced into the outcome of feeling less threatened by BC as compared to other chronic diseases for which an educational program was not offered. However, this hypothetical explanation does not explain the reduction seen in the diabetes arm participants. Further research is warranted to advance the understanding surrounding this observed change.

Besides the success of the program in prompting change, other successful outcomes of the program were the ease with which it was integrated into the normal routine of the beauty salons’ daily operation. While the cosmetologists were initially concerned that they would encounter situations they could not handle, this seldom happened. However, when such situations did occur, the program director’s goal of a prompt and effective response was reported by the stylists to be important to reassure them that they would not be left on their own to solve complex health situations which they considered to be beyond their skill level. This reassurance seemed to give them greater confidence to engage more actively in the dissemination of the educational content. The program results also suggested that engaging one cosmetologist (two in the bigger salons) was sufficient to permeate the entire salon with the health message and that salon clients concurred that cosmetologists could become effective health educators.

Anecdotal findings from the study included the cosmetologists’ reporting that the referral from community leaders, followed by the provision of individual training sessions with the PI in their salons conveyed to the other stylists and the salon’s clients the importance of the work they were undertaking. Training proved to be very important in building the cosmetologists’ confidence in conveying this relatively straightforward information. Once underway, the program could be maintained with ease by a well informed community health worker at a reasonable cost given the beneficial outcome that could be achieved. Further, individual civic-minded cosmetologists who wish to make a personal difference in reducing breast cancer mortality rates among African American women now have evidence that with proper training from their local American Cancer Society or Komen for-the-Cure Foundation, they can do so effectively.

While these results are encouraging, it is important to note that this study has several limitations. First, the study’s sample had nearly as high an attrition rate as originally anticipated. However, the intent to treat analyses suggests that this is less of a concern. Another limitation of the study is that it was accomplished in a single geographic area which may limit the ability to generalize the findings to other geographic regions. The selection of salons was based on a convenience sample. The psychometric properties of the self-report measures created for this study were unknown, which may limit the validity of the study’s findings. Another limitation is that the proportion of eligible subjects in comparison to all regular customers who were at the salons during the self-recruitment periods was not measured, which limits the ability to derive a response rate when the RAs were not present. No measure was made of how often participants of the study frequented the salon, which could have given valuable dose-response rates. Data about participants’ income and health insurance status was not collected, factors which may influence the ability to get mammograms among more affluent women who were not covered by the State’s free BC screening and treatment program for low income women. Further, states that do not offer free BC screening and treatment programs may not have the same success rate with this BC education program as states that offer such coverage. Finally, while this is a relatively inexpensive intervention strategy, there were multiple education components to it, making it unclear which of the elements actually contributed to the statistically significant changes noted. These observations suggest that further evaluation of this strategy is warranted. It is feasible that with further evaluations, the already relatively modest cost of the program can be reduced.

Similar studies utilizing cosmetologists to deliver BC education to clients in New York5 and North Carolina47 also demonstrate the feasibility of recruiting and training cosmetologists to deliver BC education, the importance of adequate training and support to develop confidence and willingness to deliver health messages, and an improvement in health behaviors.5 Results were also consistent with Wilson et al. (2008) showing an improvement in reported CBE and mammograms after the intervention. This research contributes to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the positive impact of utilizing community-based partnerships, in particular, partnership with concerned church leaders and trained cosmetologists to deliver health care messages to African American women.47

Conclusion

This randomized control trial tested a community-campus partnership between African American cosmetologists and health promotion researchers, with promising, statistically significant outcomes that evolved from an inexpensive strategy for conveying BC control information and encouraging African American women to adhere to recommended BC screening guidelines. Cosmetologists opened their salons as community-based information delivery venues for important public health messages. They learned effective ways of delivering those personalized BC screening promotion messages to their clients and encouraged their clients to share the messages with their loved ones. Ultimately, they created an environment that effectively personalized and disseminated their health promotion messages to all of their salons’ stylists and clients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, with additional support from the National Cancer Institute’s grants: R25 CA65745; P30 CA023100; U56CA92079/U56CA92081l; U54CA132379/U54CA132384; National Institutes of Health, Division of National Center on Minority and Health Disparities-sponsored (P60 MD000220) UCSD Comprehensive Research Center in Health Disparities; and NCRR UL1 RR031980. Program literature was generously donated by the American Cancer Society, the California Breast Cancer Early Detection Partnership Program, the Komen for the Cure Foundation, the American Diabetes Association, and the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute. The beauty baskets used as participant incentives were donated by Clairol.

Special thanks to the following San Diego cosmetologists and their salons whose contribution to this research study to improve the well being of African Americans was invaluable: Brenda Adams, Craig Allen, Tarva Armstrong, Charlene Baker, Barbara Ball, Jhonine Barber, Tranita Barnett, Wanda Blocker, Hazel Bomer, Tessie Bonner, Oma Black, Rachelle Brown, Al Bryant, Robert Butler, Toi Butler, William Calhoun, Lucille Cannon, Laticia Carrington, Leslie Chea, Veva Cockell, Geneva Cole, Jonna Council, Gary Davis, Kimmie Davis, Ann Denny, Denise Dulin, Josette Desrosiers, Pride Erwing, Thommie R. Flanagan, Shelton Flournoy, Flower Floyd, Brenda Forte-Pierce, Dellilah Gordon, DeBorah Green, Marilyn Hardy, Jan Harris, Shelbey Harris, Carmel Honeycutt, the late Phoebe Hutcherson, James Hyndman, Carol James, Ariella Angie Johnson, Cheryl Johnson, Ena Johnson, the late Rosemary Jones, Thea Jones, Phyllis Lee, Catherine Leggett, Darlene Loving, Ronnie Martin, Sheryl Martin, Zanola Maxie, De’Borah McCampbell, Valerie McGee, Kenisha McGruder, Janet D. Miller, Jennifer Mitchell, Lloydeisa Moore, Paula Morgan, Carl Mohammad, Sharon Mohammad, Sandra Pearson, Kia-Tana Price, Ethel M. Perkins, Jerry Piatt, Demetra Robinson, Marsha Ryder, Lynette Shine, Ann Smith, Gladys Smoot, Kandi Stephens, Beverly Taylor, Latasha Thomas, Mary Thomas, Beverly Tolbert, Bob Valero, Kim Vasser, Monica Vasser, Jeanne Walsh, Barbara Washington, Clara Watson, Kloria Wilkins, Redell Williams, Sherrice Williams, Julia Wilson, and Sabrina Woods. Special thanks also to the community leaders who enthusiastically helped the authors implement this community-based program: Victoria Butcher, Crystal Butcher, Reverend Alyce Smith- Cooper, Bishop George McKinney, Barbara Odom RN CDE, Reverend George Walker Smith, Robin Ross, and Dr. Robert Ross.

Contributor Information

Georgia Robins Sadler, Moores UCSD Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA

Celine M. Ko, University of Redlands, Redlands, CA

Phillis Wu, Moores UCSD Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA

Jennifer Alisangco, Moores UCSD Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA

Sheila F. Castañeda, San Diego State University, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego, CA

Colleen Kelly, Moores UCSD Cancer Center, La Jolla, CA

References

- 1.(ACS) ACS. California Facts and Figures. 2011:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society (ACS) Cancer Fact & Figures for African Americans 2005–2006. Atlanta American Cancer Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods SE, Luking R, Atkins B, Engel A. Association of race and breast cancer stage. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006 May;98(5):683–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Sanchez-Johnsen LA, Wells AM, Dyer A. A combined breast health/weight loss intervention for Black women. Prev Med. 2005 Apr;40(4):373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood RY, Duffy ME, Morris SJ, Carnes JE. The effect of an educational intervention on promoting breast self-examination in older African American and Caucasian women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002 Aug;29(7):1081–1090. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.1081-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hershman D, Weinberg M, Rosner Z, et al. Ethnic neutropenia and treatment delay in African American women undergoing chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Oct 15;95(20):1545–1548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan J, McKean-Cowdin R, Bernstein L, et al. An association between a common variant (G972R) in the IRS-1 gene and sex hormone levels in post-menopausal breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 Oct;99(3):323–331. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9211-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter PL, Lund MJ, Lin MG, et al. Racial differences in the expression of cell cycle-regulatory proteins in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Jun 15;100(12):2533–2542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VandeVord PJ, Wooley PH, Darga LL, Severson RK, Wu B, Nelson DA. Genetic determinants of bone mass do not relate with breast cancer risk in US white and African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 Nov;100(1):103–107. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitworth A. New research suggests access, genetic differences play role in high minority cancer death rate. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 May 17;98(10):669. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer. 2001 Jan 1;91(1):178–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu KC, Lamar CA, Freeman HP. Racial disparities in breast carcinoma survival rates: seperating factors that affect diagnosis from factors that affect treatment. Cancer. 2003 Jun 1;97(11):2853–2860. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):541–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002 Apr 3;94(7):490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelblatt JS, Kerner JF, Hadley J, et al. Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older medicare beneficiaries: is it black or white. Cancer. 2002 Oct 1;95(7):1401–1414. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon MS, Banerjee M, Crossley-May H, Vigneau FD, Noone AM, Schwartz K. Racial differences in breast cancer survival in the Detroit Metropolitan area. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 May;97(2):149–155. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griggs JJ, Sorbero ME, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003 Sep;81(1):21–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1025481505537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman LA, Kuerer HM, Harper T, et al. Special considerations in breast cancer risk and survival. J Surg Oncol. 1999 Aug;71(4):250–260. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199908)71:4<250::aid-jso11>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmore JG, Armstrong K, Lehman CD, Fletcher SW. Screening for breast cancer. JAMA. 2005 Mar 9;293(10):1245–1256. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute NC. Breast Cancer Prevention. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. [Accessed June 1, 2007];Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance Survey 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss.

- 22.Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ. Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Nov 13;166(20):2244–2252. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gullatte MM, Phillips JM, Gibson LM. Factors associated with delays in screening of self-detected breast changes in African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2006 Jul;17(1):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(ACS) ACS. Cancer Fact & Figures for African Americans 2009–2010. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams ML, Becker H, Stout PS, et al. The role of emotion in mammography screening of African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2004 Jul;15(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones BA, Patterson EA, Calvocoressi L. Mammography screening in African American women: evaluating the research. Cancer. 2003 Jan 1;97(1 Suppl):258–272. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabogal F, Merrill SS, Packel L. Mammography rescreening among older California women. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001 Summer;22(4):63–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadler GR, Escobar RP, Ko CM, et al. African-American women's perceptions of their most serious health problems. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Jan;97(1):31–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Cohn JA, White M, Weldon RN, Wu P. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors among African American women: the Black cosmetologists promoting health program. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadler GR, Meyer MW, Ko CM, et al. Black cosmetologists promote diabetes awareness and screening among African American women. Diabetes Educ. 2004 Jul-Aug;30(4):676–685. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadler GR, Thomas AG, Gebrekristos B, Dhanjal SK, Mugo J. Black cosmetologists promoting health program: Pilot study outcomes. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(1):33–37. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GRS, JS, LT, MS, CMK Cancer education for clergy and lay church leaders. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16(3):146–149. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Cohn JA, White M, Weldon R, Wu P. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors among African American women: the Black cosmetologists promoting health program. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor SLaNL. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. American Journal of Managed Care. 2004;10:SP1–SP4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gladwell M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference tipping point. Boston: Back Bay Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Alisangco J, Rosbrook BP, Miller E, Fullerton J. Sample size considerations when groups are the appropriate unit of analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2007 Aug;20(3):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conway-Phillips R, Millon-Underwood S. Breast cancer screening behaviors of African American women: A comprehensive review, analysis, and critique of nursing research. ABNF. 2009;20(4):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(8):S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halbert CH, Love D, Mayes T, et al. Retention of African American women in cancer genetics research. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2008;146(2):166–173. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing Retention in Community based Clinical Trials. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller CS, Gonzales A, Fleuriet KJ. Retention of minority participants in clinical research studies. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(3):292. doi: 10.1177/0193945904270301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wujcik D, Wolff SN. Recruitment of African Americans to National Oncology Clinical Trials through a Clinical Trial Shared Resource. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2010;21(1 Suppl):38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allman RM, Sawyer P, Crowther M, Strothers HS, Turner T, Fouad MN. Predictors of 4-Year Retention Among African American and White Community-Dwelling Participants in the UAB Study of Aging. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(suppl 1):S46. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health education monographs. 1974;2(4):328–335. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education & Behavior. 1984;11(1):1. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Institute NC. Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linnan L, Ferguson Y, Wasilewski Y, et al. Using community-based participatory reseasrch methods to reach women with health messages: Results from the North Carolina BEAUTY and health pilot project. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(2):164–173. doi: 10.1177/1524839903259497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]