Abstract

Background

Most strokes are due to blockage of an artery in the brain by a blood clot. Prompt treatment with thrombolytic drugs can restore blood flow before major brain damage has occurred and improve recovery after stroke in some people. Thrombolytic drugs, however, can also cause serious bleeding in the brain, which can be fatal. One drug, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA), is licensed for use in selected patients within 4.5 hours of stroke in Europe and within three hours in the USA. There is an upper age limit of 80 years in some countries, and a limitation to mainly non‐severe stroke in others. Forty per cent more data are available since this review was last updated in 2009.

Objectives

To determine whether, and in what circumstances, thrombolytic therapy might be an effective and safe treatment for acute ischaemic stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched November 2013), MEDLINE (1966 to November 2013) and EMBASE (1980 to November 2013). We also handsearched conference proceedings and journals, searched reference lists and contacted pharmaceutical companies and trialists.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of any thrombolytic agent compared with control in people with definite ischaemic stroke.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors applied the inclusion criteria, extracted data and assessed trial quality. We verified the extracted data with investigators of all major trials, obtaining additional unpublished data if available.

Main results

We included 27 trials, involving 10,187 participants, testing urokinase, streptokinase, rt‐PA, recombinant pro‐urokinase or desmoteplase. Four trials used intra‐arterial administration, while the rest used the intravenous route. Most data come from trials that started treatment up to six hours after stroke. About 44% of the trials (about 70% of the participants) were testing intravenous rt‐PA. In earlier studies very few of the participants (0.5%) were aged over 80 years; in this update, 16% of participants are over 80 years of age due to the inclusion of IST‐3 (53% of participants in this trial were aged over 80 years). Trials published more recently utilised computerised randomisation, so there are less likely to be baseline imbalances than in previous versions of the review. More than 50% of trials fulfilled criteria for high‐grade concealment; there were few losses to follow‐up for the main outcomes.

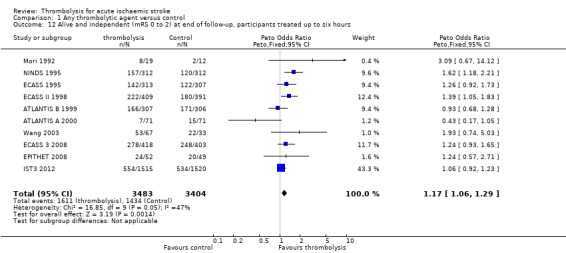

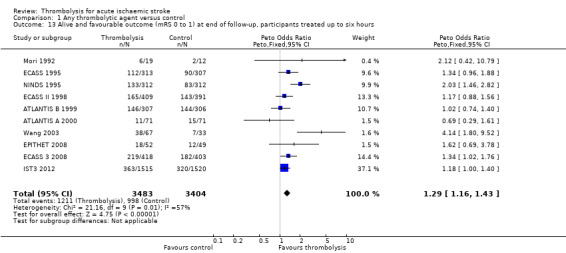

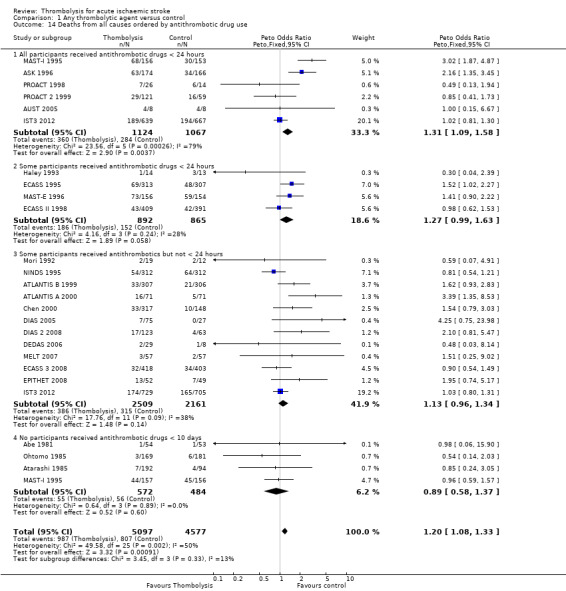

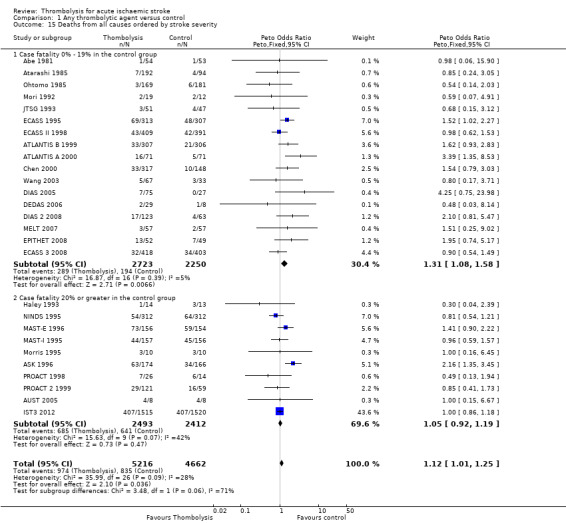

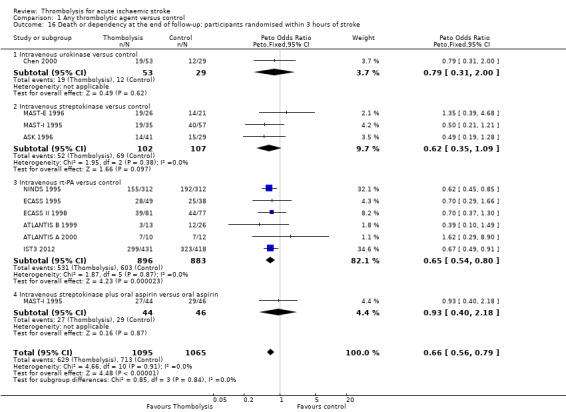

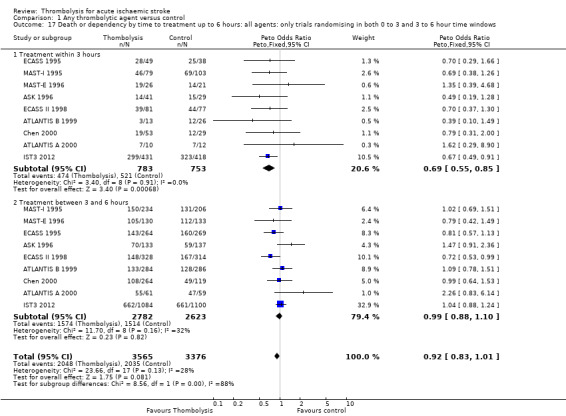

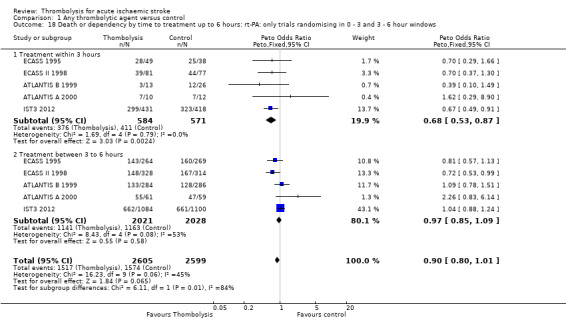

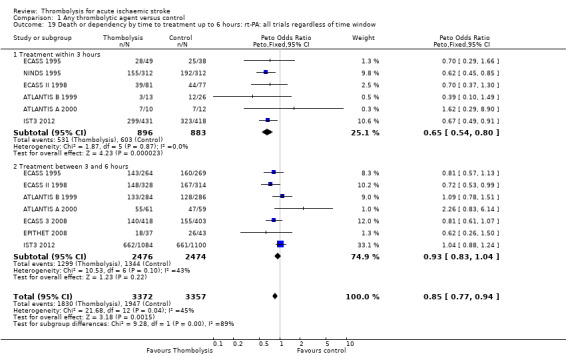

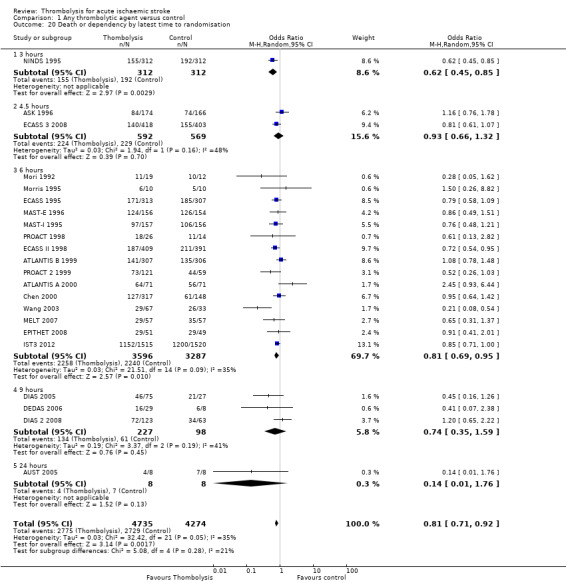

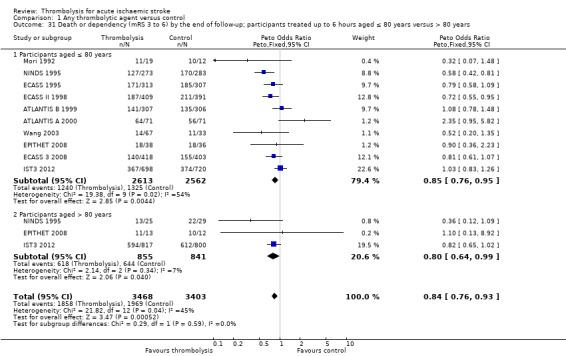

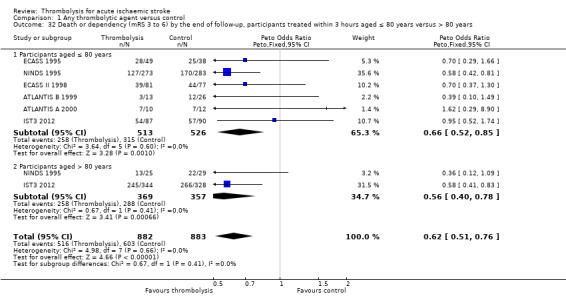

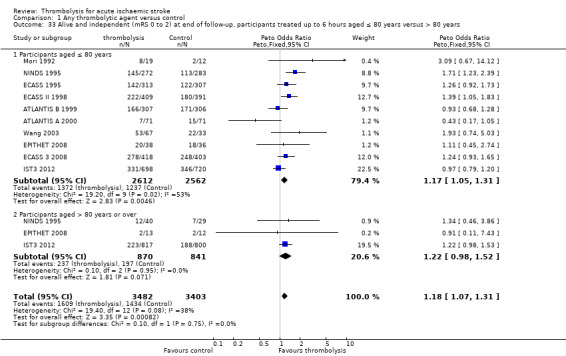

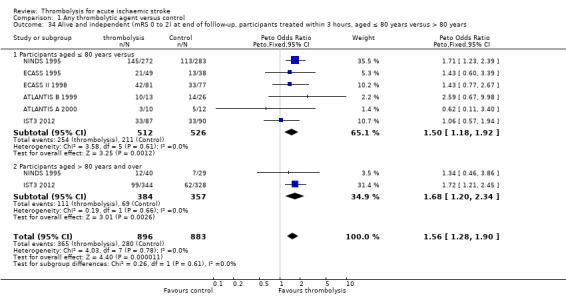

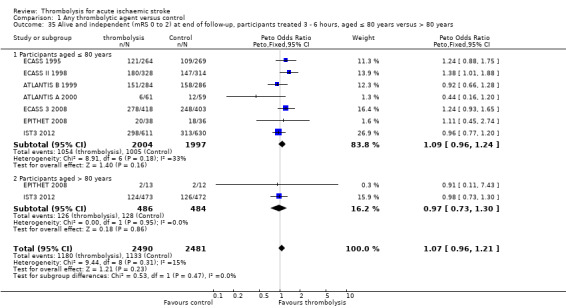

Thrombolytic therapy, mostly administered up to six hours after ischaemic stroke, significantly reduced the proportion of participants who were dead or dependent (modified Rankin 3 to 6) at three to six months after stroke (odds ratio (OR) 0.85, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 0.93). Thrombolytic therapy increased the risk of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (OR 3.75, 95% CI 3.11 to 4.51), early death (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.44 to 1.98; 13 trials, 7458 participants) and death by three to six months after stroke (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.30). Early death after thrombolysis was mostly attributable to intracranial haemorrhage. Treatment within three hours of stroke was more effective in reducing death or dependency (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.79) without any increase in death (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.21; 11 trials, 2187 participants). There was heterogeneity between the trials. Contemporaneous antithrombotic drugs increased the risk of death. Trials testing rt‐PA showed a significant reduction in death or dependency with treatment up to six hours (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93, P = 0.0006; 8 trials, 6729 participants) with significant heterogeneity; treatment within three hours was more beneficial (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.80, P < 0.0001; 6 trials, 1779 participants) without heterogeneity. Participants aged over 80 years benefited equally to those aged under 80 years, particularly if treated within three hours of stroke.

Authors' conclusions

Thrombolytic therapy given up to six hours after stroke reduces the proportion of dead or dependent people. Those treated within the first three hours derive substantially more benefit than with later treatment. This overall benefit was apparent despite an increase in symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage, deaths at seven to 10 days, and deaths at final follow‐up (except for trials testing rt‐PA, which had no effect on death at final follow‐up). Further trials are needed to identify the latest time window, whether people with mild stroke benefit from thrombolysis, to find ways of reducing symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage and deaths, and to identify the environment in which thrombolysis may best be given in routine practice.

Plain language summary

Clot‐dissolving drugs for treating ischaemic stroke in the early stages

Question

We wanted to compare the safety and efficacy of clot‐dissolving (thrombolytic) drugs versus placebo or no treatment in the early stages of ischaemic stroke to see if clot‐dissolving drugs improve outcome after stroke.

Background

Most strokes are due to blockage of an artery in the brain by a blood clot. Prompt treatment with clot‐dissolving (thrombolytic) drugs can restore blood flow before major brain damage has occurred and could mean that people are more likely to make a good recovery from their stroke. Thrombolytic drugs can also, however, cause serious bleeding in the brain, which can be fatal. Thrombolytic therapy has now been evaluated in many randomised trials in acute ischaemic stroke. The thrombolytic drug alteplase has been licensed for use within three hours of stroke in the USA and Canada, and within 4.5 hours in most European countries. The numbers of people receiving this treatment successively are increasing.

Study characteristics

We identified 27 trials with a total of 10,187 participants in searches conducted up to November 2013. Most data come from trials testing one drug (recombinant tissue Plasminogen Activator, rt‐PA) given into a vein up to six hours after acute ischaemic stroke, but several other drugs were also tested and at different times to treatment after stroke and given into an artery in the brain rather than into a vein in the arm. All trials compared a clot‐dissolving drug with a placebo (control) group. Most trials included participants with moderate to severe stroke. All trials took place in hospitals that were used to treating people with stroke. Differences between trials mean that not all trials contribute information to all outcomes, but we have used all available data. Most trials included participants after a computed tomography (CT) brain scan had excluded a brain haemorrhage as the cause of symptoms (a few trials used magnetic resonance brain scanning instead).

Key results

There is general agreement between the earlier trials and the one recent trial added in this update (IST‐3) for all main outcomes, and between the 12 trials that tested rt‐PA and the 15 trials that tested other clot‐dissolving drugs. The main difference between IST‐3 and earlier trials was that IST‐3 had many participants above 80 years. Clot‐dissolving treatment can reduce the risk of long‐term dependency on others for daily activities, in spite of there being an increased risk of bleeding in the brain which also increased the risk of early death. Once the early bleeding risk had passed, at three or six months after stroke, people given clot‐dissolving drugs were more likely to have recovered from their stroke and to be independent, especially if they had been treated within the first three hours after stroke. Older people benefited as much as younger people. Giving aspirin at the same time as clot‐busting drugs increased the risk of bleeding and should be avoided. Further analyses of individual patient data factors such as findings on brain scanning before treatment, and of different ways of giving the treatment, may give more information than the summary data that we used here. Meantime, people who think that they are experiencing a stroke should get to hospital quickly, be assessed by a stroke doctor, have a brain scan and receive clot‐dissolving treatment as fast as possible. They should not hesitate by thinking that they will be 'too old' for treatment. The treatment is very effective if started within three hours of stroke and definitely improves outcome if given up to 4.5 hours after stroke, but later than that the effects are less clear and are still being tested in trials. More information is needed from trials in people with mild stroke to see if the benefit of clot‐dissolving drugs outweighs the risk of haemorrhage.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence comes mostly from well‐conducted randomised trials run by stroke experts. Some trials (8/27) were run by companies that make the clot‐dissolving drugs, but most trials (19/27, including most participants) were funded by Government or charity sources independently of drug companies. These results apply to a wide range of people with a wide range of severities of stroke and other medical conditions.

Background

Description of the condition

Acute ischaemic stroke is a major cause of death and disability worldwide. Most strokes are due to blockage of an artery in the brain by a blood clot (ischaemic stroke) e.g. from the heart or neck arteries.

Description of the intervention

Thrombolytic drugs derive from naturally‐occurring enzymes that dissolve thrombus as part of the natural clotting cascade. Some are extracted from biological samples (e.g. urokinase, desmoteplase) and others are manufactured (e.g. recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA), or recombinant pro‐urokinase).

How the intervention might work

Clot‐dissolving (thrombolytic) drugs may reduce brain damage from a stroke by restoring the blood flow if given rapidly enough after stroke, but may also cause serious bleeding in the brain.

Why it is important to do this review

An overview of the literature on thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke in 1992 (Wardlaw 1992) identified six randomised trials of various thrombolytic drugs including a total of just 700 participants. A Cochrane review published in 1995 (Wardlaw 1995) updated the original 1992 review. It was updated again in 1999 (3478 participants in total) (Wardlaw 1999), in 2003 (5727 participants) (Wardlaw 2003b), in 2009 (7152 participants) (Wardlaw 2009) but even so, many essential questions remained unanswered: How big is the overall benefit? What is the latest time window in which the treatment is still beneficial? Which grades of stroke severity and which types of stroke, as judged clinically and on brain imaging, are more likely to respond favourably to treatment? Should people aged over 80 years receive thrombolysis? Which types of patients are most likely to be harmed by treatment, and which to benefit from it (e.g. with or without other major medical conditions like cardiac arrhythmias, diabetes, hypertension, or other disorders and concomitant medication) (Wardlaw 2002)? To answer these questions reliably, and in particular to be able to tailor treatment to the individual, more data are needed from new randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Meanwhile, the thrombolytic drug alteplase (rt‐PA) was licensed for use within three hours of stroke in the USA and Canada, and up to 4.5 hours in most European countries, and an increasing number of people now receive the treatment. Guidelines recommended that thrombolysis should be delivered by a clinical team with suitable training and experience and in a setting with appropriate facilities (ESO Stroke Guidelines 2008; NICE Stroke Guideline 2008). A general review of the use of thrombolytic therapy in clinical practice and the clinical service required to deliver it was provided in a book on the management of stroke (Warlow 2008).

This updated review includes all trials completed and made public since 2009, as well as additional data published since 2009 from trials included in earlier versions of the review. The total number of participants is now 10,187, more than a 10‐fold increase since the review was initiated in 1990 and an increase of more than 40% since 2009. Although many of the data now come from trials testing intravenous rt‐PA within the first six hours after stroke onset, the more recent trials are exploring alternative methods for selecting participants and extending time windows, e.g. through use of advanced brain imaging. The upper age limit of 80 years, stroke severity and new imaging data are also analysed. This systematic review includes these data and provides a convenient and up‐to‐date summary of the evidence.

Objectives

To determine whether, and in what circumstances, thrombolytic therapy might be an effective and safe treatment for acute ischaemic stroke. We wished to determine whether:

-

thrombolytic therapy increases the risk of death:

within the first two weeks of stroke; or

at long‐term follow‐up;

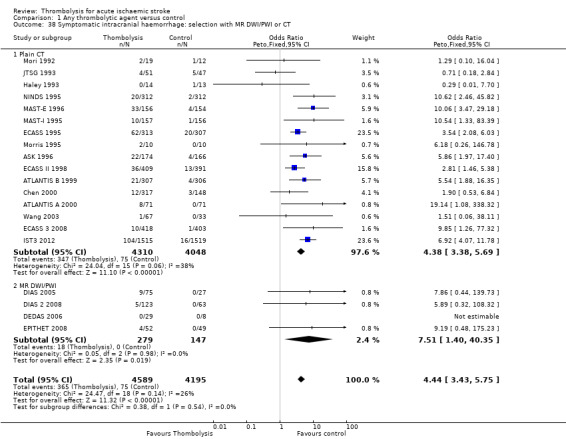

thrombolytic therapy increases the risk of symptomatic or fatal intracranial haemorrhage, or symptomatic infarct swelling;

thrombolysis reduces the proportion of people dead or dependent at long‐term follow‐up, in spite of any early hazard, so that there is an overall net benefit.

We wished to undertake exploratory analyses to examine whether:

thrombolytic therapy interacts with antithrombotic therapy to increase the hazard;

the balance of risk and benefit with thrombolytic therapy may vary with the severity of the stroke;

the latest therapeutic time window for effective treatment can yet be determined;

whether the effect of thrombolysis is different in people aged over 80 compared with under 80 years of age;

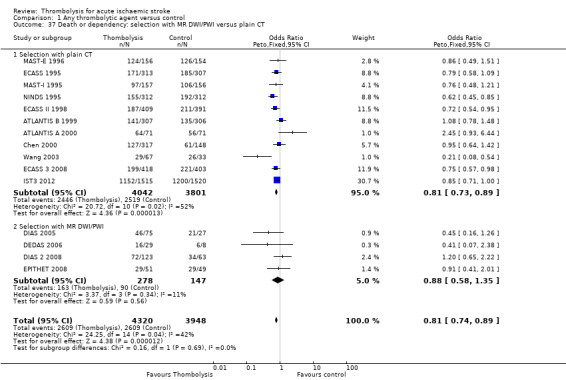

whether people selected for treatment using MR diffusion/perfusion imaging had better effect of thrombolytic treatment than those selected using computed tomography (CT) brain imaging;

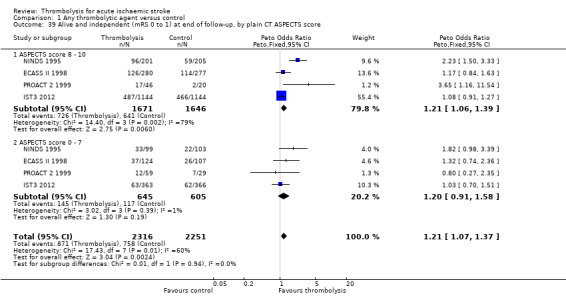

whether individual findings on CT brain imaging identified people in whom the effect of thrombolysis was different;

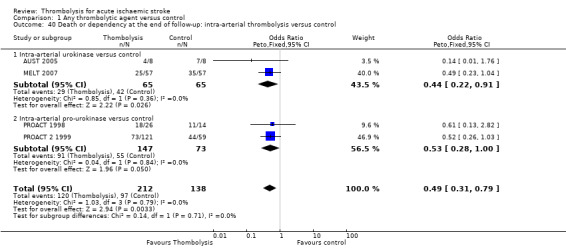

whether the effect of intra‐arterial therapy differed from intravenous therapy and explained any of the heterogeneity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought to identify all truly randomised unconfounded trials of thrombolytic therapy compared with placebo or open control in people with acute ischaemic stroke. We excluded trials that were not truly randomised, such as dose‐range‐finding studies, and trials that included thrombolytic treatment in the control group. We included trials in which the exact method of randomisation was unknown, even after correspondence with the authors, if the available information suggested that the randomisation was not likely to be biased. We also included trials that were not originally analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis if information on outcome could be obtained for all randomised participants, thus allowing us to perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Types of participants

We included trials of participants with a definite acute ischaemic stroke (CT or magnetic resonance (MR) scanning having excluded intracranial haemorrhage prior to randomisation).

Types of interventions

We included all types of thrombolytic drug, given in any dose, by the intravenous or intra‐arterial route: urokinase (UK, also known as u‐PA), recombinant pro‐urokinase (rpro‐UK), streptokinase (SK), recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA) including duteplase, lumbrokinase (LK), and desmoteplase.

We excluded trials that were confounded by the treatment or control group receiving another active therapy which had not been factored in to the randomisation (for example, thrombolytic drug plus another agent versus placebo, or thrombolytic drug versus another agent).

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were death or dependency, as defined by modified Rankin score of 3 to 6, and death at the end of follow‐up. We considered all other outcomes as secondary.

We assessed the following.

Deaths from all causes within the first seven to 10 days after treatment.

Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage (SICH): either symptomatic (that is, temporally associated with a deterioration in the person's neurological state), or fatal (that is, leading directly to death), and occurring within the first seven to 10 days. Note that symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage includes haemorrhagic transformation of the infarct, haemorrhage elsewhere in the brain remote from the infarct, and haemorrhage into the spaces surrounding the brain. Definitions of SICH vary between trials and therefore we have used the SICH data as defined by each trial's primary definition rather than attempting to standardise the definition.

Fatal intracranial haemorrhage.

Deaths within the first seven to 10 days not due to intracranial haemorrhage.

Symptomatic infarct swelling (oedema).

Deaths occurring between the end of the first seven to 10 days and three to six months.

Deaths from all causes during the whole trial follow‐up period.

Poor functional outcome at the end of follow‐up. This was the primary outcome measure for the review and was defined as death or dependency, measured by the modified Rankin or Barthel scales, at the end of the trial follow‐up period. Poor functional outcome (the converse of good functional outcome) is the most clinically relevant and important measure of outcome, since the aim of treatment should be not merely to avoid death but also to decrease dependency among the survivors; that is, to increase the proportion of independent survivors and conversely to reduce the risk of survival with serious disability. Dependency in the present analysis was defined as a score of between 3 and 5 inclusive on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Some would prefer a definition of 'good outcome' (independence) including Rankin 0 and 1 only; therefore, wherever possible we sought data on the number of participants in each individual Rankin category so as to compare poor functional outcome defined as mRS 2 to 6 with the definition of 3 to 6. Where data were not available for mRS 3 to 6, we used mRS 2 to 6 instead, rather than excluding the trial from analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for all trials in all languages using the following overlapping methods, and arranged translation of relevant papers published in languages other than English.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group's Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor on 18 November 2013. In addition, we carried out comprehensive searches of MEDLINE (Ovid) (1966 to November 2013) (Appendix 1) and EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to November 2013) (Appendix 2). We developed the search strategies for MEDLINE and EMBASE with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the following conference proceedings and stroke and neurological journals: Stroke, Cerebrovascular Diseases, International Journal of Stroke, Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, Neurology and Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry published to March 2014.

We checked multiple international conference proceedings on stroke and specifically on thrombolysis since 1991. These include all European Stroke Conferences (since 1992, annual since 1994), all International Stroke Conferences hosted by the American Heart Association (annual), all World Stroke Conferences (biannual), all Thrombolysis in Acute Ischaemic Stroke symposia (biannual).

We examined reference lists quoted in thrombolytic therapy papers.

We made direct contact with principal investigators of trials in Europe, North America, Japan, China, and Australasia.

We have been in regular contact with the manufacturer of rt‐PA, and other companies involved in ongoing studies of thrombolysis identified from the Washington Internet Stroke Center Register of ongoing trials (www.strokecenter.org).

For previous versions of this review:

We handsearched the following journals from 1979 to April 1994: Japanese Journal of Stroke, Clinical Evaluation, Japanese Journal of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, and Rinsho Ketsueki (we obtained translations of the non‐English language publications from people in whose native language the paper was published);

We contacted 321 pharmaceutical companies for more information about trials known to exist from the above efforts, and for information on any trials which were so far unknown to us (the last systematic contact was made in December 1997); all companies except one (which was known to be doing a trial in any case) responded, and no trials were identified that we did not already know about.

Data collection and analysis

This review builds on a continuous data collection process that started in 1989.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JW, VM) screened the records obtained from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full paper copy of the remaining studies and the same two review authors selected truly randomised trials comparing a thrombolytic drug with placebo or open control in people with acute ischaemic stroke, brain imaging having excluded cerebral haemorrhage and other structural causes of stroke‐like symptoms. We sought additional unpublished information from the principal investigators of all the trials that appeared to meet our inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. The selection for 2003 update was verified by EB.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JM and VM) checked the data extraction and resolved any discrepancies or uncertainties by discussion or clarification with the principal investigator. We aimed to extract the number of participants originally allocated to each treatment group in each trial to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis if the trial had not already been presented in this way.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias as specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 (March 2011), Chapter 8 (Higgins 2011). We assessed whether the method of randomisation would allow allocation concealment, the adequacy of efforts to blind treatment administration and outcome assessment. For each included trial we collected information about:

the method of randomisation (including information on allocation concealment);

blinding of treatment administration;

blinding of outcome assessment; and

whether an intention‐to‐treat analysis was done, or could possibly be done.

We provide detailed 'Risk of bias' tables for the trial included since the last update.

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted the number of participants in the treated and control groups who had:

died within the first seven to 10 days;

developed any intracranial haemorrhages, symptomatic or fatal intracranial haemorrhage early after the stroke (within the first seven to 10 days);

developed symptomatic (including fatal) infarct swelling;

died by the end of the trial follow‐up; and

were dependent on others in activities of daily living (mRS 3 to 5) by the end of the trial follow‐up period (the converse is the number who were alive and independent at the end of follow‐up).

We also extracted data to perform subgroup analyses on time to treatment, age, stroke severity, prior or concomitant antithrombotic drug use, and attempted to find information on pretreatment brain imaging findings, blood pressure, and diabetes (details below).

Unit of analysis issues

Our definition of SICH included people who died or deteriorated clinically as a result of intracranial haemorrhage. This could be either secondary bleeding into the infarct or new bleeding at an anatomically separate site elsewhere in the brain or its surrounding spaces after randomisation, confirmed by CT or MR scanning or post‐mortem examination. We have defined 'early after the stroke' as within the first seven to 10 days, as the trials each tended to use a slightly different time point, but all had collected information on intracranial haemorrhage certainly within the first 10 days. Many symptomatic haemorrhages actually occurred within the first few days of the stroke. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of SICHs because some people died without a CT scan or post‐mortem examination. Thus the true number with SICH may be higher than that suggested by these data. On the other hand, heightened awareness of an association between haemorrhagic transformation and thrombolysis may mean that the investigators too readily attributed any neurological deterioration following treatment to intracranial haemorrhage, even if the amount of blood was small. A review of published CT findings suggests that, at least for some trials, SICH included people with very large swollen and oedematous infarcts with trivial amounts of haemorrhage within them (ECASS 1995; NINDS 1995). Therefore, it is also possible that the risk of intracranial haemorrhage has been overestimated (Von Kummer 2002). The ECASS trial (ECASS 1995) did not report the number with SICH, but whether the radiological appearance of the haemorrhage suggested haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct or parenchymatous haematoma (and its size). Most parenchymatous haemorrhages were associated with symptoms, so we used the number of participants with parenchymatous haematoma as the number with symptomatic haemorrhages.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial investigators to obtain all unpublished missing data where possible. Where data were still missing or had not been collected in the original trial, then that trial did not contribute to the relevant outcome. We clarified missing or unclear data with the principal investigator. The outcomes in two studies were very clearly described in the original texts and verification with the principal investigators was not necessary (Haley 1993; Morris 1995).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for heterogeneity between trial results using the I² statistic. Heterogeneity might arise from a wide variety of factors, such as the design of the trials, the type of participants included, the use of concomitant treatments like aspirin or heparin, ancillary care during the acute treatment period or rehabilitation, lack of availability of certain data for a particular trial so that a trial appears as missing for a particular outcome, or simply by the play of chance, particularly in small trials (Deeks 2001; Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We have endeavoured to include data from all trials on all prespecified outcomes, obtained from secondary publications or the trial investigators if unpublished. We assessed the likelihood of missing trials using a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We calculated odds ratios (ORs) for each outcome (that is, the ratio of the odds of an unfavourable outcome among treatment‐allocated participants to the corresponding odds amongst controls), which we calculated using the Peto fixed‐effect method (APT 1994), and the random‐effects method for outcomes if there was significant heterogeneity between trials. We calculated absolute numbers of events avoided (or caused) per 1000 patients treated using the risk differences method provided in the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012) and also as the straight percentages calculated from the number of events per number randomised in the treated and control groups. However, please note that these events per 1000 treated data should be regarded with caution as they may produce misleading results, since the absolute risk amongst controls varies between trials.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We examined the effect of stroke severity, age under or over 80 years, time from stroke to treatment and the effect of having a large infarct on plain CT (ASPECT score 7 or less) on outcome after thrombolysis. We assessed the effect of time by several approaches: we examined the effect of time in all trials regardless of what time windows they contributed to, then in only those trials that contributed to all time windows, and then by latest time to randomisation. These approaches were used to maximise use of available data and minimise bias by excluding some trials from some analyses (e.g. the NINDS 1995 trial only recruited participants up to three hours and therefore would not contribute to an analysis comparing treatment administered within three hours with that administered between three and six hours, where inclusion was restricted to trials which included participants in both time windows). We used the proportion who died in the control group to estimate the severity of stroke. We assessed:

effect of time to treatment; the number of participants who had symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage, died or were dependent at the end of follow‐up according to whether they had been treated within three hours of the stroke or later than three hours (in trials which randomised participants beyond three hours after the stroke);

the number of participants aged over or under 80 years who had symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage, died or were dependent at the end of follow‐up;

the number of participants who were dead or dependent at the end of follow‐up according to whether they had been assessed for inclusion in a trial using CT scanning or MR diffusion‐ and perfusion‐weighted imaging (DWI/PWI);

the number of participants alive and independent (mRS 0 to 1) at end of follow‐up according to whether they had visible or not‐visible or small or large infarction on plain CT, measured by the ASPECT score.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined primarily the effect of the thrombolytic drug in all studies for all drugs combined. However, we also examined the effect of different thrombolytic drugs (streptokinase, urokinase, rt‐PA). We assessed whether the effect of thrombolysis on functional outcome varied with the definition of dependency (mRS 2 to 5, instead of 3 to 5). Additionally, we compared trials which included participants on the basis of plain CT scanning versus those which used diffusion/perfusion MR imaging or perfusion/angiography CT imaging. We stratified trials by the proportion of participants given aspirin or heparin within the treatment period by time after stroke;

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register identified 19 potentially relevant new or ongoing trials, of which only one was completed and relevant (IST3 2012). Five trials are ongoing (DIAS‐3; DIAS‐4; DIAS‐J; EXTEND; WAKE‐UP 2011). Three trials are awaiting classification (FRALYSE; Lin 2006; TESPI): TESPI has recently been completed but not yet reported, and the other two are thought to have been completed but have not yet been published. The remainder of the publications were not relevant. The search of MEDLINE and EMBASE identified 3958 references, which included many additional publications to trials that were already in the review, and several that were relevant to another review (Wardlaw 2013), but none that was relevant to this review.

Included studies

We include 27 trials, involving 10,239 randomised participants, but data for only 10,187 participants were available for inclusion in the review (Abe 1981; ASK 1996; Atarashi 1985; ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; AUST 2005; Chen 2000; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; IST3 2012; JTSG 1993; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; Mori 1992; Morris 1995; NINDS 1995; Ohtomo 1985; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003). This review includes all possible available information about all trials in an effort to provide as complete a record as possible of the available data on thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. The NINDS trial (NINDS 1995) was conducted in two consecutive parts, A and B, but published in one paper, so is included as one trial in this review. Although the USA Food and Drug Administration review of the primary analysis of the NINDS trial referred to an 'on‐treatment' analysis, the analysis was actually 'intention‐to‐treat' as no participants who had been entered into the trial were excluded from that analysis (NINDS 1995). Reasons for these comments and further analyses are provided in the Clinical Reviews submitted by Genentech to the USA Food and Drug administration in support of the license application for alteplase (www.fda.gov/cder/biologics/products/altegen061896.htm; see Clinical Review 2, pages 18 to 20).

The trials performed in the 1980s (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985) were methodologically different to the trials performed from the 1990s onwards. The 1980s trials used very low doses of thrombolytic drug, given daily intravenously for several days, and started up to five or 14 days after the stroke. The trials from the 1990s onwards used a single large dose of thrombolytic drug (in the region of 80 mg to 100 mg rt‐PA or equivalent), given intravenously or intra‐arterially, in most trials, within three, six, nine or 24 hours of the stroke. The 1980s trials did not collect data on functional outcome and therefore only the 1990s‐onwards trials contribute to the analysis of death or dependency. All trials, however, contributed to analyses of intracranial haemorrhage and death by the end of follow‐up (although very few deaths or intracranial haemorrhages occurred in the trials in the 1980s). However, it is possible to see in the figures what effect the exclusion of these early trials would have on the overall results.

The MAST‐I trial (MAST‐I 1995), which tested intravenous streptokinase and oral aspirin given within six hours of stroke onset in a two‐by‐two factorial design, is the only trial to have tested for an interaction between thrombolytic and antithrombotic drugs in a randomised trial; the comparison of streptokinase plus aspirin versus aspirin from MAST‐I 1995 is included in this review (separated from the MAST‐I 1995 data in the absence of aspirin) because it represents the only available randomised evidence on this important interaction. As there was a significant adverse interaction between streptokinase and aspirin, which we felt was important to highlight, the data for the participants receiving streptokinase in the presence or absence of aspirin are presented separately (that is, streptokinase versus control separate from streptokinase with aspirin versus aspirin). It would not be methodologically appropriate to exclude MAST‐I 1995 participants allocated aspirin because in most other trials, some antithrombotic agents were used, and while it is possible to identify the proportion of participants in the trial that received antithrombotic treatment, it is not possible to identify and then exclude the individual participants.

Types and severities of strokes included

The selection of participants was based initially on clinical criteria to diagnose the stroke sub‐type (cortical versus lacunar versus posterior circulation):

eight trials randomised all types of ischaemic stroke: cortical, lacunar and posterior circulation (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS 3 2008; Haley 1993; IST3 2012; MAST‐I 1995; NINDS 1995; Wang 2003);

two trials included cortical and lacunar strokes (ASK 1996; Chen 2000);

five trials included only participants with symptoms of hemispheric cortical ischaemia (ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; EPITHET 2008; MAST‐E 1996; Morris 1995);

six trials included participants with angiographically proven occlusion of the internal carotid or middle cerebral artery (JTSG 1993; MELT 2007; Mori 1992; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999) or vertebrobasilar arteries (AUST 2005);

three trials included presumed 'thrombotic' stroke of most severities and excluded presumed cardio‐embolic strokes (although it is not clear whether artery‐to‐artery embolism counted as 'embolic' in this context) (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985);

three trials included participants with 'tissue at risk' as identified by MR DWI/PWI or CT perfusion imaging (DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008).

Most trials used a stroke severity scale, such as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) or Scandinavian Stroke Scale (SSS) or developed their own neurological stroke severity scale to measure the severity of the stroke at baseline.

All trials excluded people who were in a coma; most trials did not randomise many participants who were drowsy except one (MAST‐E 1996) in which 50% of the participants were drowsy or stuporous at randomisation.

Age of included participants

Only seven trials had no upper age limit at all and included also very elderly participants (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; EPITHET 2008; IST3 2012; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; Ohtomo 1985). EPITHET included 25 participants aged over 80 years and IST‐3 included 1617 participants aged over 80 years.

Seven trials had an upper age limit of 85 years (ASK 1996; AUST 2005; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999).

The NINDS trial (NINDS 1995) initial protocol stated an upper age limit of 80 years. However, this was removed after 188 participants had been recruited into Part A of the trial on 30 March 1992, and thereafter 69 participants over the age of 80 were randomised (the oldest participant was 90) (www.fda.gov/cber/products/altegen061896.htm; Clinical Review 2, page 27).

All the remaining trials, including all the other rt‐PA trials, (except EPITHET 2008; and IST3 2012), had an upper age limit of 80 years.

The upper age limit in two trials (Chen 2000; MELT 2007) was 75 years.

Visible infarction on the CT scan at randomisation

Three trials specified that the pre‐randomisation CT had to be normal (JTSG 1993; MELT 2007; Mori 1992).

One trial excluded people with early visible infarction (Wang 2003).

Six trials specified that the pre‐randomisation CT scan had to be normal or only show ischaemic changes in less than one‐third of the middle cerebral artery supply territory (ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Wang 2003).

Two trials excluded people with mass effect and midline shift on CT (PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999).

None of the other trials specified that people with a CT scan that showed an infarct (which was likely to be symptomatic) should be excluded, although individual doctors may have excluded these individuals in some centres depending on local opinion.

Three trials selected participants with 'tissue at risk' on the basis of DWI/PWI (DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005), or MR DWI/PWI or CT with CT perfusion imaging (DIAS 2 2008).

Time to randomisation

The maximum time interval allowed between the onset of the stroke and the start of the treatment administration varied from within three hours to up to two weeks.

Two trials randomised participants within three hours (Haley 1993; NINDS 1995).

One trial randomised participants within four hours (ASK 1996).

One trial randomised participants between three hours and 4.5 hours (ECASS 3 2008).

One trial randomised participants between three hours and five hours (ATLANTIS B 1999).

14 trials randomised participants within six hours (ATLANTIS A 2000; Chen 2000; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; IST3 2012; JTSG 1993; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; Mori 1992; Morris 1995; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003). However, please note that in three studies (MELT 2007; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999), the majority of the participants were actually randomised between three and six hours.

One trial randomised participants within three to six hours (EPITHET 2008).

Three trials randomised participants between three and nine hours (DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008).

One trial randomised participants within 24 hours (AUST 2005).

Two trials randomised participants within five days (Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985).

One trial randomised participants within two weeks (Abe 1981).

Please note that the latter three trials (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985) do not contribute data to the analysis of early deaths or of death and dependency, as early deaths were not recorded and a functional outcome measure was not used in these trials. They do contribute data to the analyses of intracranial haemorrhages and deaths by the end of follow‐up.

Drug and dosage

Trials using intravenous rt‐PA contribute 7012 of the 10,187 participants, that is, 69% of the data in this review. Data and outcomes of all included substances are reported for completeness. However, rt‐PA data are also given as appropriate.

Four trials used streptokinase (ASK 1996; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995, Morris 1995).

Twelve trials used recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA) (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; IST3 2012; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; NINDS 1995; Wang 2003).

Six used urokinase (UK) (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; AUST 2005; Chen 2000; MELT 2007; Ohtomo 1985).

Two used pro‐urokinase (pro‐UK) (PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999).

Three used desmoteplase (DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008).

The mode of administration was intravenous in most trials.

-

In all except four of the above trials, the thrombolytic agent was administered intravenously.

In two studies (AUST 2005; MELT 2007) the thrombolytic agent was given intra‐arterially into the cerebral circulation.

Two studies used recombinant pro‐urokinase (rpro‐UK) given intra‐arterially into the cerebral circulation (PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999).

Please note that trials testing lumbrokinase did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. Ongoing trials are testing other new thrombolytic agents such as microplasmin or tenecteplase (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies).

The doses were:

the streptokinase dose was 1.5 MU (as used to treat acute myocardial infarction) in four studies (ASK 1996; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; Morris 1995);

the rt‐PA dose was similar to that used to treat acute myocardial infarction at 1.1 mg/kg to a maximum of 100 mg in one study (ECASS 1995); about 20% less at 0.9 mg/kg to a maximum of 90 mg in eight studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; IST3 2012; NINDS 1995); either 0.7 or 0.9 mg/kg in one study (Wang 2003); and about one‐third of 0.9 mg/kg in two studies (JTSG 1993; Mori 1992). All streptokinase and rt‐PA doses were administered by intravenous infusion through a peripheral arm vein, over one hour.

the urokinase dose in the Chinese UK trial (Chen 2000) was 1.5 or 1.0 MU intravenously over 30 minutes (considered to be similar to that used to treat acute myocardial infarction); in three studies (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985) the urokinase dose was much lower than the equivalent for acute myocardial infarction and was administered intravenously once daily for seven days. The intra‐arterial urokinase dose in one study (AUST 2005) was up to 1.0 MU maximum and in another study (MELT 2007) was up to 60,000 IU;

the rpro‐UK dose was 6 mg in PROACT 1998 and 9 mg in PROACT 2 1999: in both trials it was given intra‐arterially, through a catheter with its tip embedded in the occluding thrombus;

the dose of desmoteplase was 62.5 μ/kg, 90 μ/kg or 125 μ/kg in one study (DIAS 2005), and 90 μ/kg or 125 μ/kg in two studies (DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2 2008).

Concomitant use of antithrombotic treatment

One trial (MAST‐I 1995) compared streptokinase versus control among participants who were either allocated to aspirin, or allocated to no aspirin, started within six hours of stroke onset, in a factorial randomisation (in the groups randomised to receive aspirin, it was continued for 10 days).

Antithrombotic use was not randomly assigned in any other trial and its permitted use varied:

in one study ASK 1996) all participants were to receive 300 mg aspirin starting within four hours of the streptokinase infusion and continued daily thereafter;

in one study (PROACT 1998) all participants were to receive 1000 u/hour intravenous heparin during the trial angiogram, reduced to 500 u/hour halfway through the trial;

in one study (PROACT 2 1999) all participants were to receive intravenous heparin 500 u/hour for four hours starting at the time of the angiogram infusion;

in one study (AUST 2005) all participants received 5000 IU heparin intra‐arterially followed by intravenous heparin to a target activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 60 to 80 seconds for a minimum of two days followed by oral warfarin to a target international normalised ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 2.5 for six months;

in one study (MAST‐E 1996) aspirin and intravenous heparin were allowed to start at any time and continue for any time (about 25% of participants received aspirin or heparin within 24 hours and 75% within the first week of the stroke);

in three studies (ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008) subcutaneous heparin was allowed within 24 hours of the stroke (and thereafter) and aspirin after 24 hours (in ECASS II 1998, about 20% of participants were taking aspirin at the time of their stroke and 54% of rt‐PA‐treated participants received subcutaneous heparin within the first 24 hours, but we are unsure of the corresponding numbers for ECASS 1995, or ECASS 3 2008, nor how many participants in either trial received aspirin or heparin after 24 hours);

in one study (Haley 1993) a few participants received antithrombotic drugs within 24 hours and thereafter;

in 10 studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; Chen 2000; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; IST3 2012; MELT 2007; Mori 1992; NINDS 1995) no antithrombotic drugs were allowed within 24 hours but aspirin was allowed thereafter;

in three studies (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985) antithrombotic drugs were not allowed during the seven days of treatment infusion, but could be used thereafter;

the antithrombotic drug use is not stated clearly three studies (EPITHET 2008; JTSG 1993; Morris 1995).

Follow‐up

Early outcome assessments were made at around seven to 10 days in most trials. Some trials also performed more frequent assessments in the first few hours and days after the trial treatment. In this review, outcome events occurring within the first seven to 10 days (whichever was the later date at which data were collected) have been used to determine the effect of thrombolytic therapy on early outcome.

The final outcome assessment was at:

about one month after the stroke (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; Morris 1995; Ohtomo 1985);

three months after the stroke (ASK 1996; ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; Chen 2000; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; MELT 2007; NINDS 1995; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003); and

six months after the stroke (AUST 2005; IST3 2012; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995).

Please note that follow‐up at six months and one year have subsequently been reported for one study (NINDS 1995), but the three‐month outcome, the primary outcome originally reported, is used in this review. This also occurred in another study (IST3 2012) where the primary six‐month outcome originally reported is used, even if the 18‐month follow‐up, of a predefined vast majority of participating countries, has been subsequently reported.

Please note that because of the difficulty of blinding the biological effect of thrombolytic therapy, it is important to ensure that outcome assessment is blinded and objective. Follow‐up should therefore be performed by individuals unaware of the trial treatment allocation either because they have not been involved in the administration of the trial treatment, or in the care of the participant during at least the first few days. In one study (MAST‐I 1995) the six‐month follow‐up was by telephone by a trained observer blind to the treatment allocation. In another study (IST3 2012) the six‐month follow‐up was blinded and performed either by postal mail or telephone by a trained observer blind to the treatment allocation. Seven studies (ASK 1996; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; EPITHET 2008; MAST‐E 1996; Wang 2003) did not specify who performed the follow‐up or that they should not have been involved in the trial treatment administration or participant care in the first 24 hours. In five studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; Chen 2000; ECASS 3 2008; NINDS 1995), follow‐up at all stages was done by a doctor who had not been involved in the randomisation or care of the participant in the first 24 hours. In four studies (ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999), follow‐up was by a mixture of individuals; if possible, by someone who had not been involved in the participant's care within the first 24 hours but this may not always have been the case.

Assessment of functional outcome

The assessment of functional outcome was by:

the Barthel Scale in four studies (ASK 1996; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; Morris 1995);

an undefined scale (no, mild, moderate or severe 'limitation') in one study (Haley 1993);

the Rankin Scale in two studies (MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995);

the modified Rankin Scale in 16 studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; AUST 2005; Chen 2000; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; MELT 2007; NINDS 1995; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003);

the Oxford Handicap Scale (OHS), a commonly used variant of the modified Rankin score, was used in one study (IST3 2012);

it was not assessed in three studies (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985).

Some trials used more than one scale to measure outcome; for example, six studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; NINDS 1995) favoured a 'Global Outcome Statistic' which involved collecting Barthel, Rankin, Glasgow Outcome Score and NIHSS scores individually and then combining the four scores. Three trials (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; Ohtomo 1985) used the 'Global Improvement Rating', which measures change in neurological status and safety outcome as a composite surrogate for functional outcome.

There are differences in the primary outcome measure used between trials, in that some used a 'poor functional outcome' and some used a 'good outcome'. The following trials sought 'dependency' (that is, whether the participant was dependent or not in activities of daily living) as a measure of poor functional outcome: two studies (MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995) defined dependency as Rankin 3 or worse, and two studies (ASK 1996; Morris 1995) defined dependency as a Barthel score of 60 or worse. In one study (IST3 2012) 'alive and independent' (OHS 0 to 2; mRS 0 to 2) was the primary measure of outcome. The 'alive and favourable outcome' (mRS 0 to 1) and ordinal analysis were included in prespecified secondary outcome analyses.

Thirteen trials sought 'good functional outcome' (that is, whether the participant had made a complete or virtually complete recovery) defining 'good outcome' as mRS 0 or 1 (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; Chen 2000; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; MELT 2007; NINDS 1995; Wang 2003).

For most trials, it has been possible to obtain data on participants in each individual Rankin (or Barthel) group, or data dichotomised on Rankin 0 to 2 versus 3 to 6, or 0 to 1 versus 2 to 6, so that dependency in this review refers to Rankin, (mRS or OHS) 3 to 5 (6 being dead) unless otherwise stated. There are only two trials for which the number of participants in individual Rankin groups is not so far available (and therefore the data shown are for Rankin 2 or worse) (ATLANTIS A 2000; PROACT 1998).

Excluded studies

We excluded two trials conducted prior to the availability of CT scanning (Meyer 1963; Meyer 1964) as there was no way of confirming that the stroke was ischaemic. One small trial of intra‐arterial streptokinase stopped prematurely after four participants had been randomised due to the impracticality of the intra‐arterial technique (Edinburgh 1991). A trial started in Hong Kong was abandoned after a few participants had been randomised because of concerns that streptokinase might cause too many haemorrhages (Hong Kong 1994) (two trials (ASK 1996; MAST‐E 1996) had both just stopped prematurely creating an adverse climate for the conduct of trials testing streptokinase). We excluded one trial (Naito 1984) after discussion with Professor T Abe (co‐investigator) as it was not possible to account for 11 of the 101 randomised participants (most of whom were in the control group). We excluded six trials conducted in China, two because of confounding (Xiang 1995; Yuan 1995), one because the duration of follow‐up was only three weeks (Pang 1993), two that evaluated oral lumbrokinase thrice daily for 21 days but within an unspecified time window and without clinical outcome assessment (Jin Urokinase metaanalysis 2000; Huang 2000), and one that assessed ahylysantifarctase but lacked clinical outcomes (Liu 1994). A further 73 trials have also been excluded due to a range of reasons given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Studies that were potentially relevant but were confounded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and the reason given.

Risk of bias in included studies

We have included 27 trials: six trials using intravenous thrombolytic therapy published prior to 1995, 17 trials from 1995 to 2012, and four trials using intra‐arterial thrombolytic therapy.

Allocation

Among the included studies 14 (52%) fulfilled criteria for high grade concealment. The concealment has successively improved over time with the development and utilisation of new randomisation methods, such as the use of a centralised computerised method with interactive interface for randomisation over the telephone or Internet.

Twelve trials used central telephone or Internet randomisation (ASK 1996; AUST 2005; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 3 2008; IST3 2012; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999). In five studies (AUST 2005; IST3 2012, MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; PROACT 2 1999), the allocated treatment was then given unblinded without a placebo. In one of the studies (IST3 2012) with the exception of 276 participants treated in the double‐blinded phase of the trial, the remaining participants (2759) were treated unblinded without placebo. In four other studies (ASK 1996; ECASS 3 2008; MAST‐E 1996; PROACT 1998) sealed prepacks of thrombolytic drug or identical‐appearing placebo were given according to the randomisation instructions.

In three trials randomisation was at the participating hospital by selection of a sealed, sequentially‐numbered, prepack (of active drug or identical appearing placebo) followed within two hours by a telephone call to the Central Trial Co‐ordinating Office to notify them of the participant and the number of the drug pack (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; NINDS 1995). In one study (NINDS 1995), the randomisation system, set up in an effort to reduce delays to treatment, led to 'out of order' trial treatment allocations in between 13 and 31 participants, which affected every subsequent participant until the error was detected, and led to participants appearing to cross between treatment allocations (more moved from rt‐PA to placebo than the other way round). Also in the interests of reducing delays to trial treatment administration, there were some participants who ultimately were not entered into the study after the pharmacy had prepared the trial pack (and therefore some discarded trial packs). Details of the randomisation are given at www.fda.gov/cber/products/altegen061896.htm; see Clinical Review 2, page 11‐12 and 18‐19.

In three trials, randomisation was by selection of a sequentially numbered, sealed drug prepack at the participating centre provided by the sponsor from a randomisation schedule drawn up centrally (ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; EPITHET 2008).

Of the remaining trials:

five trials used sealed drug prepacks of active drug or identical‐appearing placebo (Abe 1981; Atarashi 1985; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; Ohtomo 1985);

one used sealed envelopes (Haley 1993);

one used sealed drug prepacks of active drug or normal saline (as placebo) (Chen 2000);

the method was not stated in two (Morris 1995; Wang 2003).

Please note that, therefore, only two of the rt‐PA trials (ECASS 3 2008: IST3 2012) recorded the participant details centrally over the telephone or Internet prior to starting trial treatment. In one of these trials (IST3 2012) a minimisation algorithm was used to balance the study arms for key prognostic variables like stroke severity before randomisation. Several later studies have made use of modern randomisation techniques and entering key prognostic variables into the IT system before randomisation, which allows balancing of the study arms ‐ as has been introduced in one trial (IST3 2012) .

Blinding

Five trials were single‐blind without a placebo (AUST 2005; MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003). In one trial (IST3 2012) the first 276 participants were treated in the double‐blinded phase of the trial and all 2759 remaining participants were included into the open phase of the trial. All participants in the study, irrespective of study phase, were blindly assessed by postal mail or telephone by a blinded and trained observer. In PROACT 2 1999, the control group underwent catheter placement but received no infusion. All the rest were double‐blind placebo‐controlled trials. However, it should also be noted that thrombolysis, due to its effects on the coagulation system at high doses, can be difficult to blind completely due to the obvious signs of bleeding (prolonged bleeding at venepuncture sites, easy bruising, gingival or conjunctival haemorrhages, etc). Thus, provision of an identical‐appearing placebo (in the syringe) may not fully blind investigators to treatment allocation. Furthermore, as thrombolytic agents are proteins, they froth when shaken in solution with water or saline, rather like egg white mixed with water and shaken. Normal saline is therefore not an identical‐looking placebo for a thrombolytic agent. Thus, in addition to the possibilities for failure of treatment allocation concealment inherent in the randomisation methods used as outlined above, it is possible that treatment allocation could be guessed accurately by the physicians caring for the participant in the acute phase because of these biological effects. Accordingly, methods for ensuring complete blinding of treatment allocation at late follow‐up are crucial. Only one study (MAST‐I 1995) used central telephone follow‐up by a blinded trained observer. Although seven other trials specified that follow‐up was to be by a physician not involved in the acute care of the participant, it is uncertain how completely this was achieved in practice. Other trials either did not specify who should do the follow‐up, or did not make it mandatory that follow‐up was by an independent physician, so in either case follow‐up may have been carried out by the acute phase physician who could have been influenced by their knowledge of events in the acute phase.

Incomplete outcome data

All available data are included. Data on six participants were missing from the ATLANTIS B 1999 trial publication and details have not been forthcoming from the investigators, and we have not yet received data on 46 participants from the Chinese UK Trial (Chen 2000) (these participants were randomised after the trial's six‐hour time limit and have not yet been supplied). More information is available for some trials than for others, either because the trial collaborators have published very actively on various aspects of their trial, or because in some cases further information is available from other sources (for example, reports on NINDS 1995 appear on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website as part of the licence application process). The more frequent reporting or greater completeness of the data for some trials is merely a reflection that more information is available for those trials, and not intended to over‐ or under‐emphasise the actual results or quality of any particular trial (or trials) compared with others for which there is less detailed information available.

Selective reporting

We have avoided, as far as possible, any reporting bias by obtaining original data from the trial investigators where these have not been published. Only the intention‐to‐treat results are included here. In any trials where there have been exclusions, these were made prior to the breaking of the randomisation code. A strict intention‐to‐treat analysis was used in 18 studies (ASK 1996; ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; AUST 2005; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; IST3 2012; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; MELT 2007; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003), but not in any of the earlier trials. The administrative problems with randomisation in one study (NINDS 1995) led the FDA reviewer to describe the primary analysis as an 'on‐treatment analysis'. However, the primary analysis was undertaken without excluding any participants entered into the trial and was, therefore, an intention‐to‐treat analysis (www.fda.gov/cber/products/altegen061896.htm; see Clinical Review 2, page 20). For the earlier trials, with additional information from the principal investigators if necessary, we have attempted to find a final outcome for all randomised participants, rather than simply relying on the published data from which some randomised participants may have been excluded. Note that one trial (ECASS 1995) was published as intention‐to‐treat and as a 'target population' after about 20% of the randomised participants had been excluded, but only the intention‐to‐treat data have been included here.

Other potential sources of bias

Randomisation in two trials, ASK 1996 (in the over‐three‐hour group) and MAST‐E 1996, was stopped on the advice of their respective data monitoring committees after only about half of the originally intended number of participants had been randomised. One study (MAST‐I 1995) was suspended by its steering committee (in view of the stopping of MAST‐E 1996 and ASK 1996) to examine its interim results after randomising about one third of its originally intended number. Another study (MELT 2007) was discontinued on the advice of its data monitoring committee when rt‐PA was licensed in Japan in 2005. Another study (AUST 2005) was discontinued on the basis of very slow recruitment after 24 participants of a planned sample of 200 had been included. Four studies (ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; NINDS 1995; PROACT 2 1999) all reached their planned targets. One study (PROACT 1998) was stopped after completing two of its planned three dosage arms by the pharmaceutical provider. Another study (ATLANTIS A 2000) was stopped on publication of the NINDS 1995 trial, and continued in modified form as ATLANTIS B 1999, which in turn stopped in 1998 following a 'futility analysis' prompted by results from the ECASS II 1998 study. Examination of funnel plots for the main outcomes showed these to be symmetrical and therefore provided little evidence of publication bias.

Effects of interventions

See Data and analyses. Note that in each analysis, trials are grouped by thrombolytic drug and whether intravenous or intra‐arterial, with a subtotal odds ratio (OR) for that group. The overall OR for all trials appears at the bottom of each plot. Note that one study (MAST‐I 1995) appears twice in the analyses because the data in participants allocated aspirin have been entered separately from the participants allocated no aspirin. Also note that some outcomes have fewer trials contributing data than other outcomes. This is because not all trials collected data on all outcomes examined in this review, or if they did collect data on the particular outcome, it may not be available. If data were available for a particular outcome, then the trial appears listed in the relevant analysis. The 2012 systematic review and meta‐analysis of rt‐PA (Wardlaw 2012) conducted a comparison of the 11 earlier rt‐PA studies (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS 1995; ECASS 3 2008; ECASS II 1998; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; NINDS 1995; Wang 2003) and IST3 2012 on its own, and analysed the effect of adding IST‐3 to the 11 earlier trials. That analysis is not repeated here.

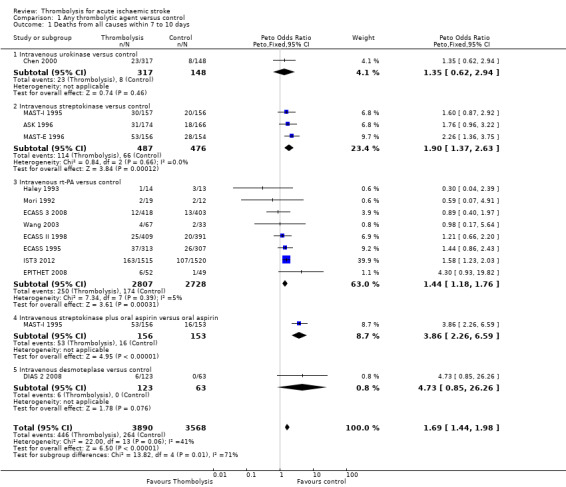

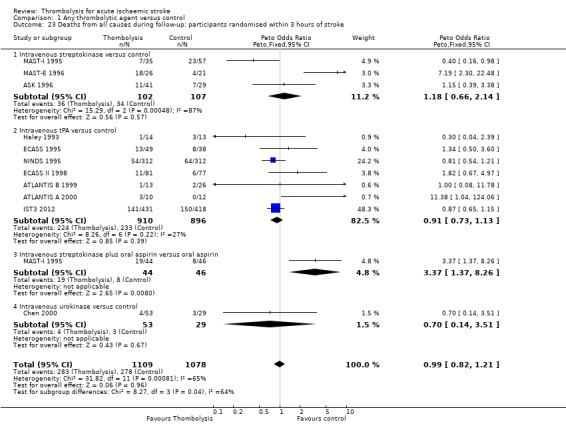

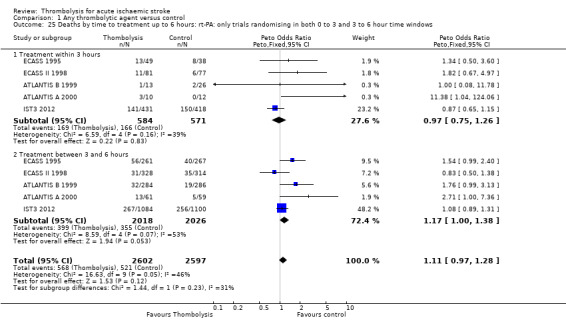

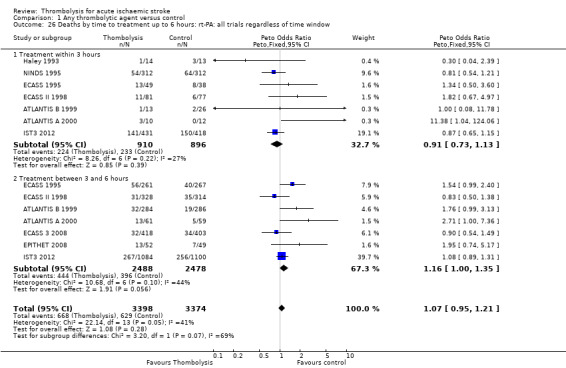

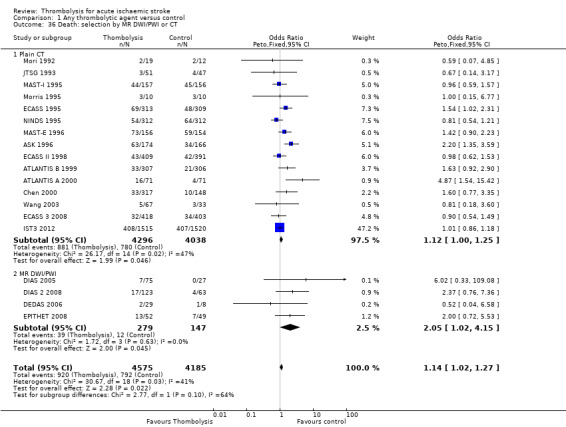

Deaths from all causes within seven to 10 days

Data on deaths occurring within the first seven to 10 days were available for 13 trials (7458 participants; Analysis 1.1). Amongst the larger and more recently completed trials, data were not available for seven trials (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; NINDS 1995; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999). There was a significant excess of early deaths with thrombolysis: 11.5% of those allocated to thrombolytic therapy died compared with 7.4% of those allocated to control (OR 1.69, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.44 to 1.98, P < 0.00001). In absolute terms, if confirmed, this is an increase of 40 (95% CI 30 to 55) early deaths per 1000 participants treated with thrombolysis. There was borderline significant heterogeneity (I² = 41%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 1 Deaths from all causes within 7 to 10 days.

Data on early deaths were available for eight trials using intravenous rt‐PA. The numerical (tabular) data on early deaths for the NINDS trial (NINDS 1995) have not been published, but the NINDS trial did publish a survival curve which suggested that fewer deaths occurred in the rt‐PA‐treated participants from 24 hours after treatment onwards. The tabular data available from the other rt‐PA trials showed a significant excess of early deaths: the OR was 1.44 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.76, P = 0.0003; 5535 participants) with no significant heterogeneity; the absolute effect was 25 more (95% CI 11 to 40 more) deaths per 1000 participants treated. In the three trials using streptokinase, there was also a significant excess of early deaths (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.63; 963 participants).

We also performed an analysis of the data using a random‐effects model. This also shows a statistically significant excess of deaths with thrombolysis of similar magnitude to the fixed‐effect analysis (all trials: OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.16, P < 0.0001; just trials of rt‐PA: OR 1.44 , 95% CI 1.18 to 1.77, P = 0.0004).

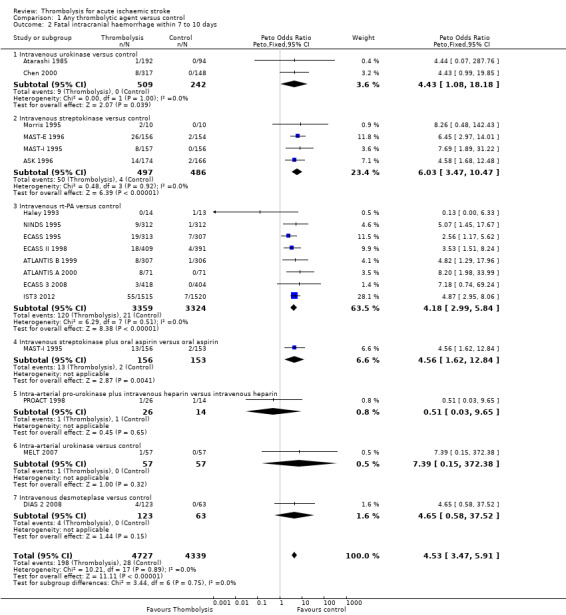

Fatal intracranial haemorrhage within seven to 10 days

Data were available from 17 trials on fatal intracranial haemorrhage (9066 participants; Analysis 1.2). There are 10 trials for which this outcome is not currently available (Abe 1981; AUST 2005; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; DIAS 2005; EPITHET 2008; JTSG 1993; Mori 1992; PROACT 2 1999; Wang 2003). This outcome may underestimate the frequency of intracranial haemorrhage since some of the participants who died without a post‐mortem examination or CT scan may have died of intracranial haemorrhage. There was a significant, approximate six‐fold increase in the rate of fatal intracranial haemorrhage with thrombolysis (4.19% of participants allocated to thrombolysis compared with 0.65% of those allocated to control, OR 4.53, 95% CI 3.47 to 5.91, P < 0.00001). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity (I² = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 2 Fatal intracranial haemorrhage within 7 to 10 days.

In eight trials using rt‐PA, there were 30 (95% CI 20 to 40) extra fatal intracranial haemorrhages per 1000 participants treated (OR 4.18, 95% CI 2.99 to 5.84, P < 0.00001; 6683 participants) with no statistically significant heterogeneity between trials (I² = 0%).

The combination of streptokinase with aspirin in one study (MAST‐I 1995) significantly increased fatal intracranial haemorrhage (OR 4.56, 95% CI 1.62 to 12.84; 309 participants), and more participants died of cerebral causes without a CT scan or autopsy who may therefore also have had intracranial haemorrhage than in the group who received aspirin alone.

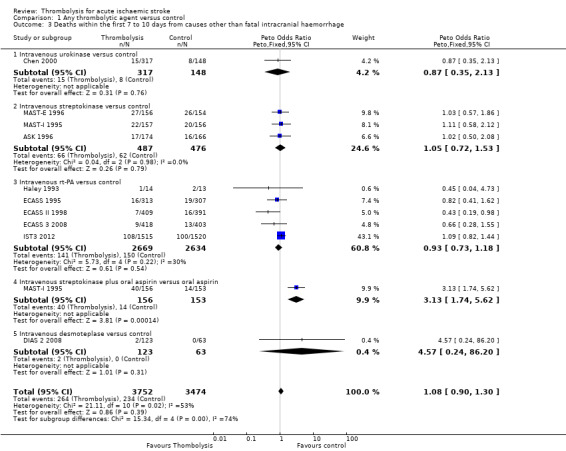

Deaths within the first seven to 10 days from causes other than fatal intracranial haemorrhage

We calculated the effect of thrombolysis on death from causes other than fatal intracranial haemorrhage for the 10 trials that provided data on both early death and fatal intracranial haemorrhage (7226 participants; Analysis 1.3). Note that, unfortunately, this excludes several large trials (ATLANTIS A 2000; ATLANTIS B 1999; DEDAS 2006; DIAS 2005; NINDS 1995; PROACT 1998; PROACT 2 1999), which did not provide data on early death. There were 264/3752 (7.0%) non‐intracranial haemorrhage deaths in the thrombolysis‐treated participants and 234/3474 (6.7%) in the control participants (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30, P = 0.39) with significant between‐trial heterogeneity (I² = 53%, P = 0.02). In comparison with Analysis 1.2 this suggests that most of the excess in early deaths of 42 per 1000 treated with thrombolysis is attributable to intracranial haemorrhage.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 3 Deaths within the first 7 to 10 days from causes other than fatal intracranial haemorrhage.

In participants treated with rt‐PA (ECASS 1995; ECASS 3 2008; ECASS II 1998; Haley 1993; IST3 2012), 141/2669 (5.2%) died within the first seven to 10 days of causes other than intracranial haemorrhage, compared with 150/2634 (5.7%) in the control group, OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.18, P = 0.54, I² = 30%; 5303 participants),

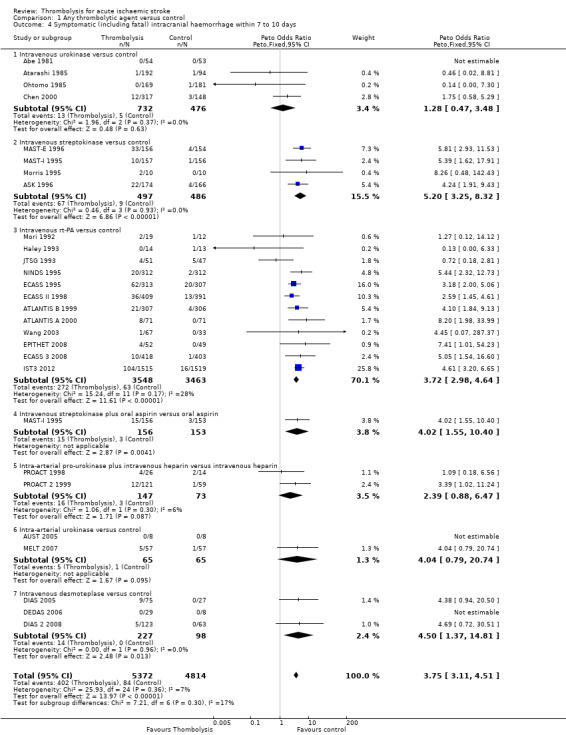

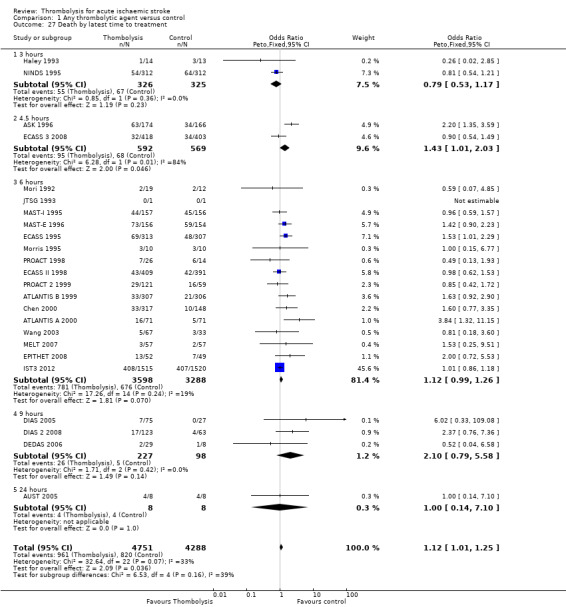

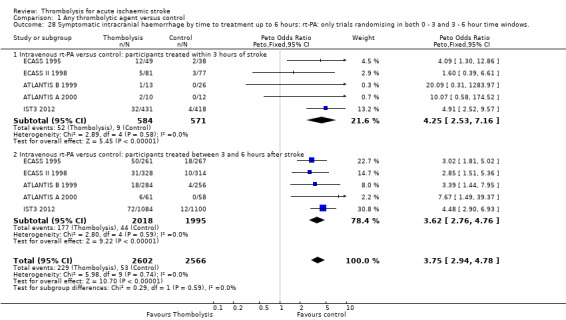

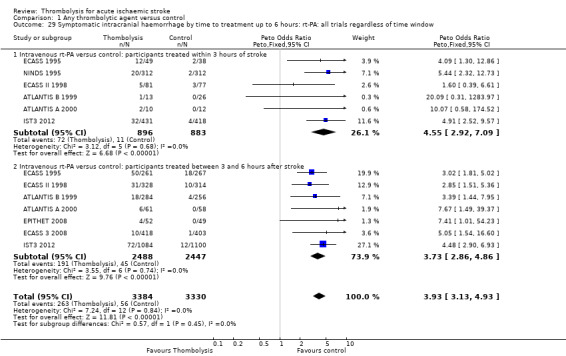

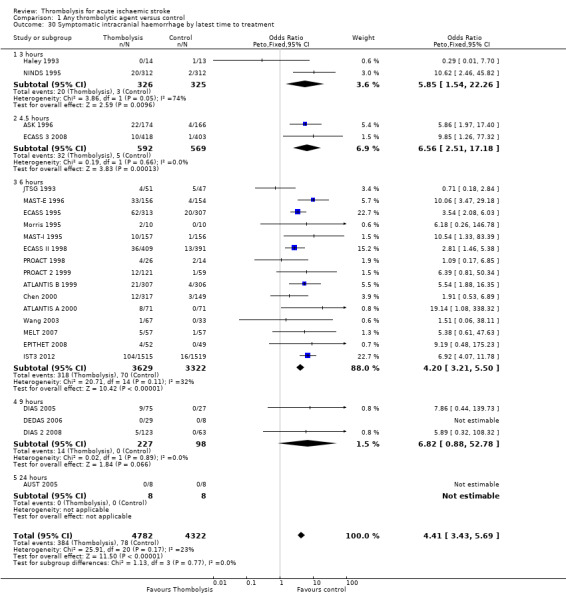

Symptomatic (including fatal) intracranial haemorrhage within seven to 10 days

All trials provided data on intracranial haemorrhage and most provided them in a form that made it clear how many participants had suffered a neurological deterioration associated with the appearance of new haemorrhage in the brain on a CT or MR brain scan or at post‐mortem examination (10,186 participants; Analysis 1.4). There was a highly significant four‐fold increase in symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage with thrombolysis in 7.5% of those allocated to thrombolysis versus 1.7% of those allocated to control (OR 3.75, 95% CI 3.11 to 4.51, P < 0.00001) with no statistically significant between‐trial heterogeneity (P = 0.36). This represents an extra 60 (95% CI 50 to 65) symptomatic intracranial haemorrhages per 1000 participants treated.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 4 Symptomatic (including fatal) intracranial haemorrhage within 7 to 10 days.

In 12 trials using rt‐PA, there were 60 (95% CI 50 to 70) extra symptomatic intracranial haemorrhages per 1000 participants treated (OR 3.72, 95% CI 2.98 to 4.64, P < 0.00001; 7011 participants) with no heterogeneity between trials (I² = 28%, P = 0.17).

Excluding the trials that used lower doses of thrombolysis and had lower rates of fatal and symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage had little effect on the overall result as they contributed relatively few of the data to this analysis.

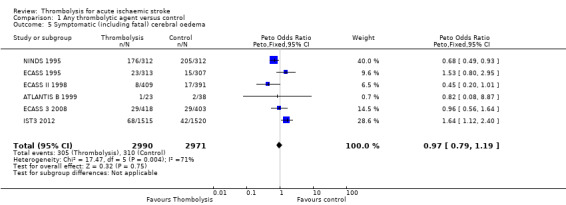

Symptomatic (including fatal) cerebral oedema

Six trials all testing rt‐PA provided data on symptomatic including fatal infarct swelling (ATLANTIS B 1999; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; IST3 2012; NINDS 1995) (Analysis 1.5; 5961 participants). There was no overall reduction in symptomatic infarct swelling with thrombolysis: 10.2% of those allocated thrombolysis had symptomatic infarct swelling compared with 10.4% of those allocated control (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.19, P = 0.75) with significant heterogeneity (I² = 71%, P = 0.004). Due to the heterogeneity we undertook an analysis according to a random‐effects model. This gave very similar results (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.51, P = 0.88), and identical heterogeneity compared with the fixed‐effect model.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 5 Symptomatic (including fatal) cerebral oedema.

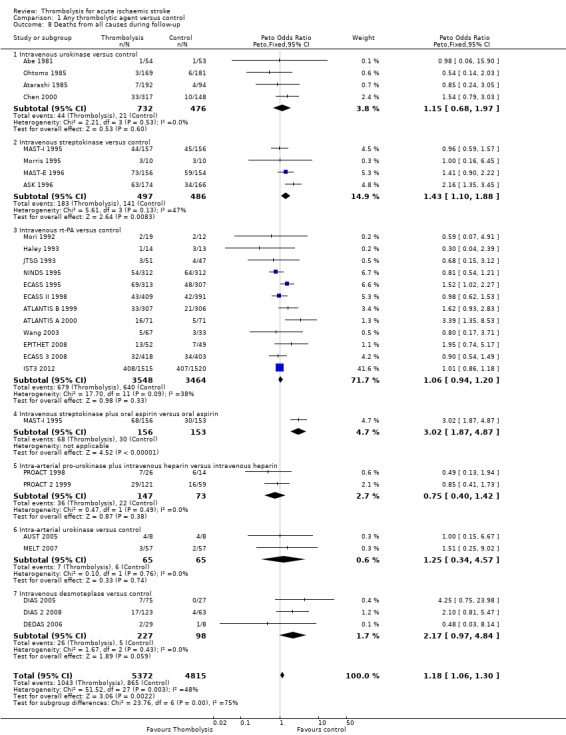

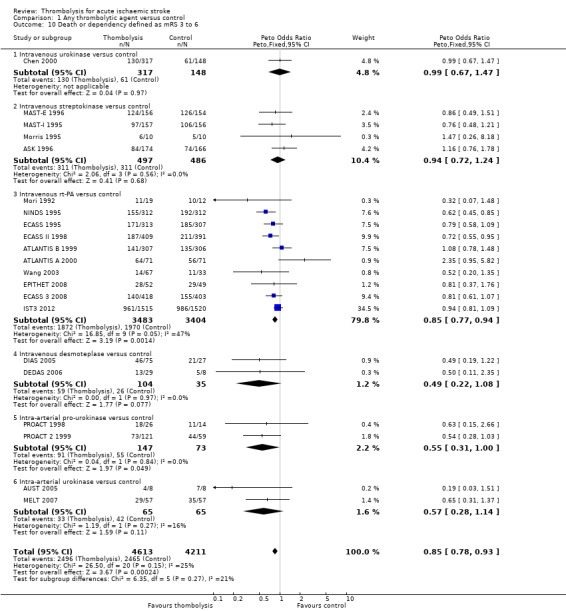

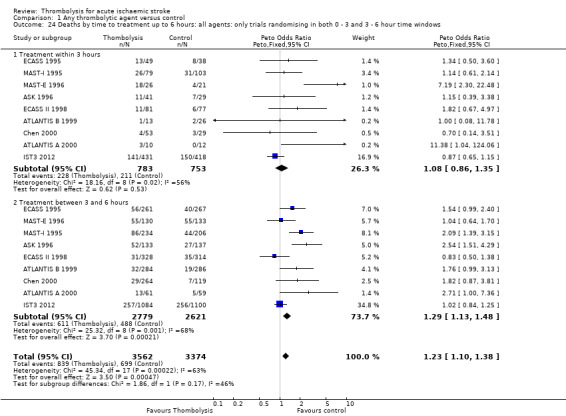

Deaths from all causes during follow‐up

Data were available for all 27 trials (10,187 participants) (Analysis 1.8). There was a modest but significant increase in deaths within scheduled follow‐up, from 18.0% in controls to 19.4% in the participants allocated to thrombolysis (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.30 , P < 0.002). In absolute terms, this represented an extra 15 (95% CI six fewer to 30 more) deaths at the end of follow‐up per 1000 participants treated with thrombolysis. There was heterogeneity between the trials (I² = 48%, P = 0.003) reflected in the fact that some trials (for example, ECASS II 1998; IST3 2012; MAST‐I 1995 (of participants allocated to the thrombolytic agent alone) and NINDS 1995) showed a non‐significant reduction and others (for example, ASK 1996, ATLANTIS A 2000 and MAST‐I 1995 (of participants allocated to the thrombolytic agent plus aspirin)) showed a significant increase in case fatality with thrombolysis.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 8 Deaths from all causes during follow‐up.

In the 12 trials using intravenous rt‐PA, there was no net effect on deaths (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.20; 7012 participants) equivalent overall to seven more (two fewer to 25 more) deaths per 1000 participants treated. The heterogeneity of treatment effect among the trials of rt‐PA was not quite statistically significant (I² = 38%, P = 0.09).

In view of the statistically significant heterogeneity for all trials (I² = 48%), we performed an analysis of the data using a random‐effects model. This also shows a statistically significant excess of deaths with thrombolysis of similar magnitude to the fixed‐effect analysis (all trials: OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.52 P = 0.02).The results for just trials of rt‐PA (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.38, P = 0.31) were also of similar magnitude as the fixed‐effect model and still without any statistical significance.

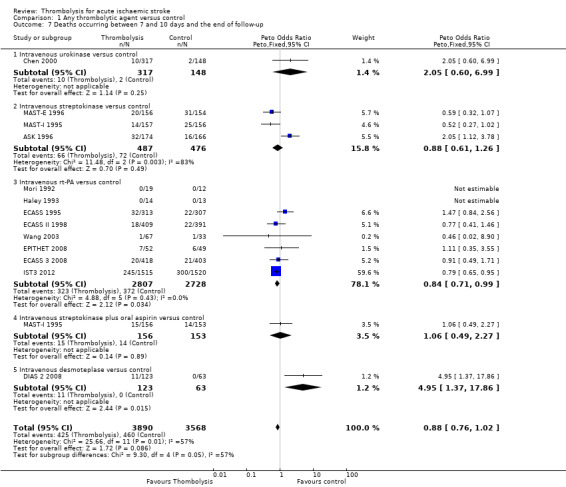

Deaths occurring between seven and 10 days and the end of follow‐up

We examined the number of deaths occurring between the first seven to 10 days and the end of follow‐up in the 13 trials that provided data for both early and late deaths (ASK 1996; Chen 2000; DIAS 2 2008; ECASS 1995; ECASS II 1998; ECASS 3 2008; EPITHET 2008; Haley 1993; IST3 2012; MAST‐E 1996; MAST‐I 1995; Mori 1992; Wang 2003). There were 425/3890 (10.9%) deaths in this period in the thrombolysis‐treated participants compared with 460/3568 (12.9%) in the control participants, a difference of 2 per 1000, OR 0.88 (95% CI 0.76, 1.02, P = 0.09; 7458 participants). There was significant heterogeneity (I² = 57%, P = 0.007) (Analysis 1.7). In eight trials testing rt‐PA, the corresponding OR was 0.84 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.99; 5535 participants) also indicating fewer deaths between seven and 10 days and the end of follow‐up. This analysis suggests that most of the deaths that occur following thrombolysis, including rt‐PA, occur in the first seven to 10 days, and that thereafter the number of deaths occurring in thrombolysis‐treated participants is very similar to that occurring in the control participants, or fewer than in the control group in trials testing rt‐PA. IST3 2012 provided data on death at six months, which suggested that the longer duration of follow‐up (six instead of three months) allowed for the deaths in the control group occurring after the first seven to 10 days (300/1520, 19.7%, versus 245/1515, 16.2% in rt‐PA treated participants) to overtake the excess of deaths due to fatal intracranial haemorrhage after rt‐PA occurring in the first seven to 10 days, leading to a net‐neutral overall effect on death at long‐term follow‐up with rt‐PA.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 7 Deaths occurring between 7 and 10 days and the end of follow‐up.

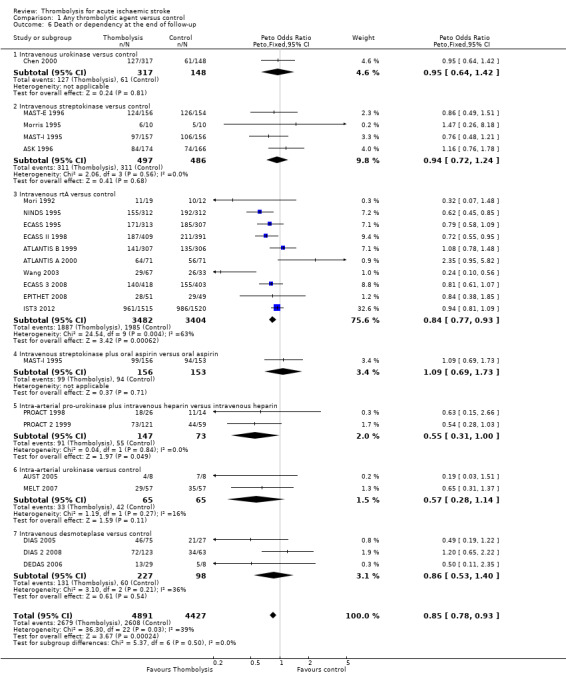

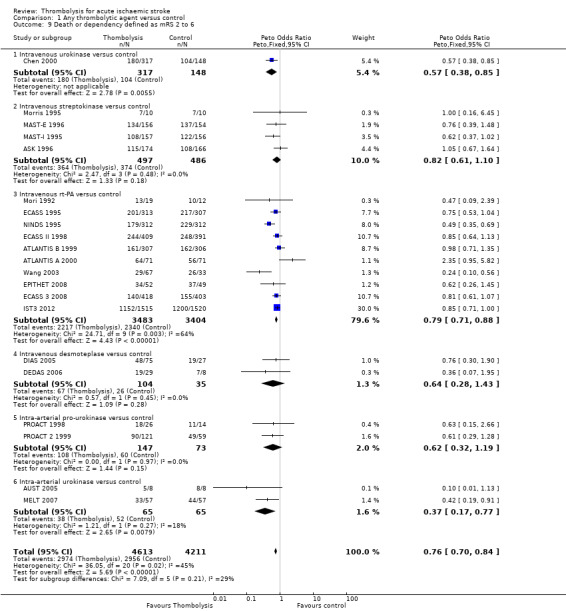

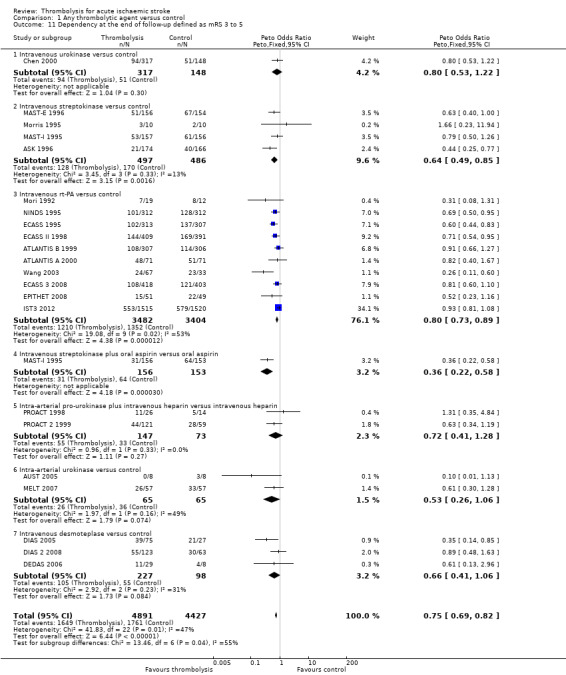

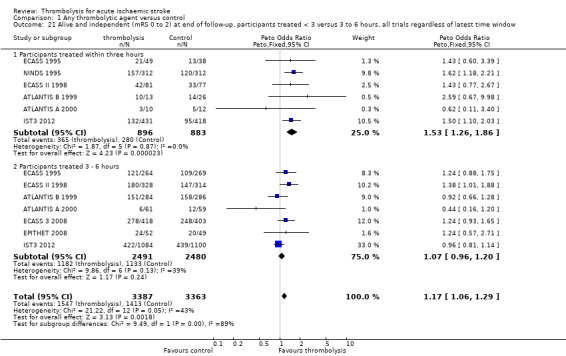

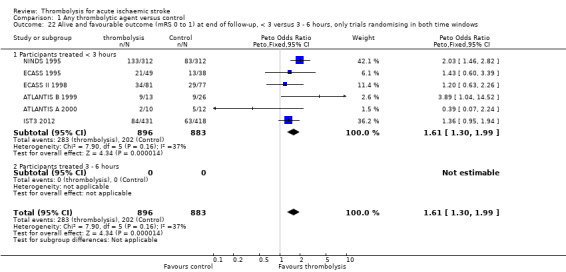

Death or dependency at the end of follow‐up

Analysable data from 22 trials (including all recently completed and large trials) on functional outcome were available for 9318 participants (Analysis 1.6). Two further trials also assessed functional outcome but the data from one (Haley 1993) were incomplete (3/27 participants were alive but lost to follow‐up), and in the other (JTSG 1993) the Barthel Scores were not available.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any thrombolytic agent versus control, Outcome 6 Death or dependency at the end of follow‐up.

There was a significant reduction in death or dependency with thrombolysis: 54.8% compared with 58.9% of those allocated to control (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.93, P = 0.0002). This is equivalent to 41 (95% CI 20 to 60) fewer dead or dependent participants per 1000 treated. There was significant heterogeneity of treatment effect between the trials (I² = 39%, P = 0.03).

For the 10 trials using intravenous rt‐PA (6886 participants), the OR was 0.84 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.93, P = 0.0006), equivalent to 40 (95% CI 20 to 65) fewer participants being dead or dependent per 1000 treated. There was significant heterogeneity of treatment effect among the trials using rt‐PA (I² = 63%, P = 0.004).

In view of the statistically significant between‐trial heterogeneity, we performed an analysis of the data on death or dependency using a random‐effects model. This gives an OR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.95, P = 0.006) for all trials, and of 0.80 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.97, P = 0.03) for just trials of rt‐PA. (Note of caution: random‐effects analyses place undue weight on smaller studies and possibly should be avoided with combined outcomes. Death and dependency actually reflect two outcomes which may 'pull' in different directions. Small studies may have more extreme results and give less reliable estimates of true treatment effect than large studies).

If an alternative definition of 'poor outcome' (Rankin score 2 to 6) is used in this analysis, and the analysis is restricted to just the 21 trials with both definitions available, then the ORs are as follows:

mRS 2 to 6 for any thrombolytic drug versus control OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.84, P = 0.00001; 8824 participants) with significant between‐trial heterogeneity (I² = 45%, P = 0.02); for just rt‐PA trials, the OR was 0.79 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.88, P = 0.00001; 6887 participants), but also with significant heterogeneity (I² = 64%, P = 0.003) (Analysis 1.9);