Abstract

Brain development is an energy demanding process that relies heavily upon diet derived nutrients. Gut microbiota enhance the host’s ability to extract otherwise inaccessible energy from the diet via fermentation of complex oligosaccharides in the colon. This nutrient yield is estimated to contribute up to 10% of the host’s daily caloric requirement in humans and fluctuates in response to environmental variations. Research over the past decade has demonstrated a surprising role for the gut microbiome in normal brain development and function. In this review we postulate that perturbations in the gut microbial-derived nutrient supply, driven by environmental variation, profoundly impacts upon normal brain development and function.

Keywords: glucose, gut microbiota, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, metabolism, microbiota-gut-brain axis, neurodevelopment, short chain fatty acids, β-hydroxybutyrate

Introduction

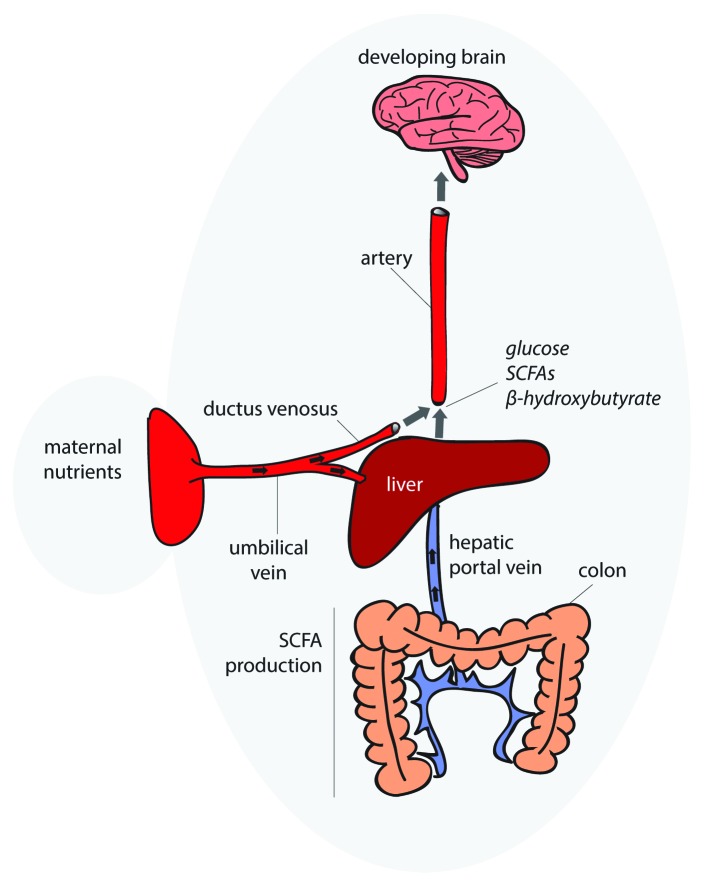

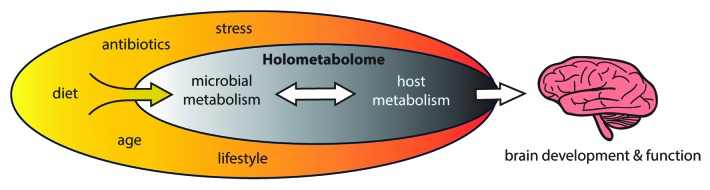

The diverse community of microorganisms lining the gastrointestinal canal has co-evolved with its host to build a mutually beneficial relationship. This location supports resident microbes with a reliable supply of nutrients and favorable temperatures for biological and biochemical reactions. A major role of the gut microbiome is to digest dietary fiber, otherwise refractory to the host’s enzymatic repertoire, into metabolic byproducts such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs); acetate, propionate, and butyrate.1 Throughout evolution, these products of bacterial fermentation were likely to have afforded significant metabolic and immune fitness advantages to the host-microbe entity, referred to as the holobiont.2 Consequently, gut microbial metabolism is deeply intertwined with host metabolism3,4 and is an important contributor to the dynamic transfer of energy from the diet to the host (Fig. 1). During early life (conception to adolescence), this transfer of energy is essential to the expansion of tissues that require vast amounts of nutritional support for proper development, particularly the immune and central nervous system. Environmental perturbations which alter the collective metabolic capacity of the microbiome, and thus the availability of valuable metabolic precursors5 may directly, or indirectly, modify brain developmental trajectories and function in later life.

Figure 1. The host-microbe holometabolome. Environmental variations (yellow oval) leading to changes in the gut microbial metabolic capacity can induce alterations and compensations within the metabolic network. The consequence of a perturbed holometabolome will likely affect many different body systems, including brain development. The diet is likely to be a major environmental modulator of this system.

Here we provide a survey of the current literature and convey our perspective on the metabolic communication between the host and gut microbiome to highlight its relevance to neurodevelopment and brain function. We will focus primarily on the potential of SCFAs to affect the brain through (1) directly modulating host chromatin structure and gene transcription, (2) use as an energy source for ATP generation, and (3) the incorporation of SCFAs into energy reserves. We will then examine the potential of gut microbial driven changes in host systemic metabolism to impact brain development and function.

In utero, the developing embryo receives a maternally dictated nutrient supply. Postnatally, the newborn is exposed to a vast number of microbes, vertically transmitted from the maternal microbiome, which, in combination with protective maternal antibodies and nutrients provided by the breast milk, secures the first dramatic growth expansion in immediate early life. Together with early host intestinal response genes, breast milk is likely to shape the initial repertoire of early colonising microbes6,7 through it being both a source of microbes per se8-10 and as a source of nutrients for the developing microbiome. These initial interactions are likely to be important steps in mediating infant development through shaping the efficacy of gut microbial nutrient harvest from the diet11 and providing metabolites important for developmental progression.12 Importantly, although the gut microbiome has been implicated as a modulator of normal brain development and function within an early life developmental window13,14 (recently reviewed in refs. 15-17), the involvement of host-microbe co-metabolism in this processes remains largely unknown.

The early life environment plays a pivotal role in shaping the way an individual’s brain develops and functions,18 including variations in nutritional intake (recently reviewed).19 Although the human brain represents 2% of the body’s mass, it consumes 20% of the whole body energy budget, whereas in rodents, the brain mass represents only ~0.2% of body mass and thus consumes only 2% of the body’s energy budget.20 This demonstrates the brain as being an incredibly energy demanding organ, regardless of species, but also that the human brain may be more vulnerable to metabolic dysfunction than rodents. Classic epidemiological studies on Dutch Hunger Winter sufferers revealed that nutrient deprivation within distinct gestational periods is associated with schizophrenia,21,22 anti-social personality disorder,23 and major affective disorders,24 thus emphasizing the importance of adequate early-life nutritional support for normal brain development and function. For the developing brain, we hypothesize that changes in gut microbial metabolism during distinct critical developmental windows, such as in in early-life, may be key to understanding predispositions to various neurological disorders.

Endogenous Microbial Inhabitants: A Forgotten Organ

It is estimated that the number of microbial cells constituting the human gut microbiome outnumber the host’s by 10:1 and the number of genes by 100:1. The microbiota contains a myriad of organisms including yeasts, protozoa, archaea, and bacteria, with estimations at over 1000 species.25 Many of the beneficial effects that gut microbiota impart on host physiology is due to the production of SCFAs in the colon. Importantly, production of these metabolites is believed to be a major driving force behind the metabolic interactions between the host and gut microbiota.4,26

The significance of gut microbiota in host metabolism is perhaps best demonstrated by observations in mice lacking microbiota, referred to as germ-free, which are leaner than their colonised counterparts27, despite consuming more food26, and have a severely reduced survival rate upon starvation.28 In addition, antibiotic treatment during early life increased adiposity, which was associated with shifts in the gut microbial composition in mice.29 These data demonstrate that gut microbes aid in nutrient retrieval and storage to enhance the hosts ability to fulfil caloric requirements. It is therefore plausible that changes to the gut microbial composition, and consequently the production of SCFAs, may interfere with the vital nutrient supply required for the intensely energy demanding process of brain development.

Microbial SCFA Production and Systemic Trafficking

The SCFA yield from a typical western diet constitutes 5–10% of a host’s daily energy needs.1,30 Factors limiting gut microbial production of SCFAs include (1) the availability of fermentable dietary fiber,31 (2) microbiota expressing the necessary machinery to import, degrade and metabolise dietary fiber into SCFAs,32,33 and (3) intra microbiome metabolic collaboration.34 In addition, changes to the gut microbiome composition through antibiotic use,3,6,35,36 mode of delivery,36,37 caloric restriction,38 age,39-41 gastric surgery,42,43 psychological stress,44-46 geography,41 and diet6,47-54 are all either known to, or likely to, alter SCFA production throughout an individual’s lifetime.

Once produced in the colon, SCFAs are then either used locally as an energy source by colonocytes (particularly butyrate55) or drained to the liver via the portal vein where their fate depends on the metabolic status of the host. Typically, SCFAs are incorporated into energy stores via lipogenesis or gluconeogenesis4 however, they can also be distributed directly into the blood stream for dissemination to organs throughout the body,56,57 including the brain (Fig. 2). Acetate, propionate and butyrate display decreasing penetration into the blood stream respectively. This may be due to the preferential use of butyrate as an energy source by colonocytes and possibly decreasing diffusion due to their respective increase in carbon chain length.58 Consistently, acetate appears to be the most abundant of these metabolites in the peripheral circulation followed by propionate and then butyrate.57,59-61 In humans, dietary manipulations designed to enhance colonic SCFA production lead to increases in serum acetate, propionate, and butyrate concentrations.62,63 These changes can persist for hours as was demonstrated in men who ate a fiber rich evening meal and exhibited morning serum butyrate levels comparatively higher compared with those who ate a meal relatively low in fiber.64 These findings indicate that the concentrations of serum SCFAs are dynamic and fluctuate in response to dietary fiber manipulation.

Figure 2. Gut microbiota supply nutrients to the developing brain. This hypothetical model illustrates the route by which gut microbiota supply nutrients to the developing brain. Upon draining to the liver via the hepatic portal vein, SCFAs are incorporated into either lipogenic or gluconeogenic pathways for energy storage, depending on the metabolic state of the host, or disseminated directly into the bloodstream. Gut microbial regulation of blood metabolites which are required to build a healthy brain may modify developmental trajectories. In utero, nutrients for normal brain development are transported to the infant across the placental barrier via the umbilical vein. Two thirds of the nutrient and oxygen loaded blood passes through the liver while the remaining bypasses the liver via the ductus venosus and is diverted directly into the blood stream of developing fetus.

Transcriptional and Metabolic Regulation by SCFAs

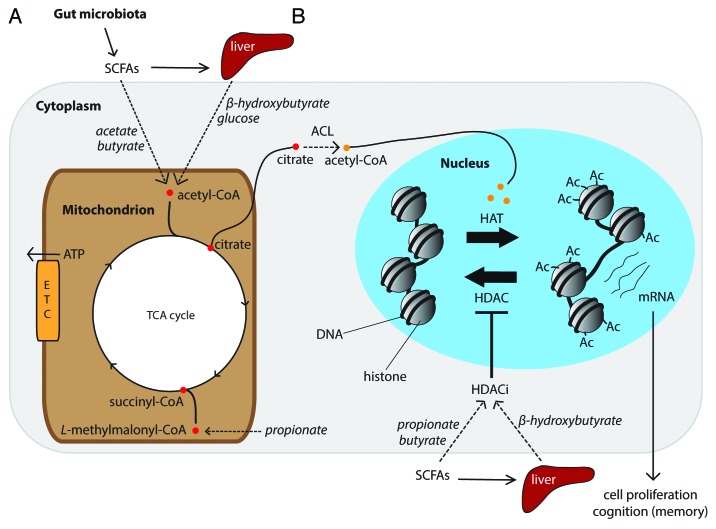

In mitochondria, SCFAs can be oxidized to generate ATP via the TCA cycle. Through a series of intermediate steps the carbon backbones of acetate and butyrate are converted into acetyl-CoA which then enters the TCA cycle proximally, whereas propionate is converted to succinyl-CoA to enter at the distal end of the TCA cycle (Fig. 3A). In addition to their role as a source of ATP, SCFAs are also capable of host chromatin remodelling leading to global changes in host gene expression. In the nucleus, histones package host DNA into a conformational unit referred to as a nucleosome. Histone acetylation is accomplished by histone acetyl transferases (HATs). HATs transfer an acetyl groups onto histone lysine residues that neutralizes its positive charge and, in doing so, weakens the electrostatic interaction between histones and the negatively charged DNA (Fig. 3B). This loosening of the chromatin structure mediates active transcription by allowing greater access of transcription machinery to promoter regions. Conversely, transcription can be repressed by removal of the acetyl moieties from an acetylated lysine by a group of enzymes referred to as histone deacetylases (HDACs) (Fig. 3B). This latter form of transcription repression can be blocked by HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) (Fig. 3B). SCFAs, particularly butyrate and propionate, and even acetate (albeit at a far lower potency), are capable of inhibiting HDAC activity.65,66 Therefore gut microbiota-derived SCFAs likely possess the capacity to influence host gene expression by remodeling host chromatin structure. It is thereby plausible that dietary induced fluctuations in colonic SCFA production reflected in host serum,57,62,63 is capable of altering host gene expression far beyond the colon, including organs such as the liver, muscle, and brain.

Figure 3. External metabolic cues regulate histone acetylation via the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This hypothetical model illustrates how gut microbial regulated serum metabolites, which are readily used by mitochondria to generate ATP, may influence host cell gene transcription. (A) SCFAs are produced in the colon and disseminated directly into the blood stream or trafficked to the liver and released as glucose or β-hydroxybutyrate, depending on the host’s metabolic status. These metabolites are then used by cells within the CNS to generate ATP via the TCA cycle. (B) ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) uses mitochondrial derived citrate to generate acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm and nucleus. In the nucleus, histone acetyl-transferases (HATs) transfer the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA onto histone lysine residues to facilitate cell proliferation and the expression of genes important for learning and memory. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups from histones to suppress gene transcription. HDACs can be inhibited bya histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), including gut microbial regulated serum metabolites, e.g., β-hydroxybutyrate, butyrate, and propionate. This is illustration is not to scale.

Epigenetic regulation by histone acetylation has recently been shown to be intimately connected with host cell metabolism. In a landmark study, it was demonstrated that acetyl-CoA, derived from glucose and ATP-citrate lyase (ACL), can provide the acetyl substrate for histone acetylation67 (Fig. 3B). Gut microbiota have been shown to modify the availability of circulating energy metabolites in blood, including glucose and other metabolites readily used to generate ATP via the TCA cycle.68 It is therefore plausible that changes to the gut microbiota composition, and consequent perturbations in serum metabolite concentrations, can mediate changes to brain histone acetylation (Fig. 3B). This may be of particular significance if fluctuations in these circulating metabolites occur during early life when epigenetic control of developmental trajectories is vital to the later life function of a given organ, especially the brain due to its high energy demands. Similarly, during aging, a reduction in the availability of serum energy metabolites, as has been observed in a mouse model for aging and cognitive decline,69 may also mediate reduced histone acetylation observed in the aging mouse hippocampus.70

In vitro experiments demonstrate that butyrate can modify neuronal gene expression and signal transduction,71,72 but to our knowledge, such high butyrate concentrations used in these experiments (1–6 mM) have not been reported in human or rodent blood under physiological conditions. In vivo models exploiting the potent HDACi activity of butyrate, again albeit at concentrations unlikely to be observed under normal conditions, has revealed its surprising ability to enhance cognitive function. Consistently, butyrate has been shown to reinstate histone acetylation in the mouse hippocampus (a brain region important for learning and memory) and was correlated with improved learning and memory.73 Similar results were observed in models for depression,49 age-associated cognitive decline,70 Alzheimer disease,74 and Huntington disease.75 The corollary of these combined findings might suggest that reduced HDACi activity, potentially as a consequence of reduced gut microbial metabolite production or age dependent metabolite trafficking deficiencies of such metabolites,76 may underlie changes to the way an individual’s brain functions, including psychological state and neurodegenerative processes.

Gut Microbiota Regulation of Energy Reserves

At birth, newborns must adapt to a relatively high fat, low carbohydrate diet provided by the mother’s milk instead of a glucose rich nutrient supply across the placental wall. This metabolic shift relies heavily upon the infant being able to produce and utilize the ketone (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate as an energy source during intermittent feeding within the suckling and weaning period,77 a process referred to as ketogenesis.78 When blood glucose is low, ketones are produced through fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver and then disseminated via the blood stream. This glucose replacement ensures sufficient nutritional support for the body, especially the brain, during infant development. Similarly in adults, when blood glucose is low due to prolonged exercise, starvation or a ketogenic diet (low carbohydrate); millimolar concentrations of (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate are produced as an alternate energy source to support the adult’s metabolic needs.79,80 Gut microbiota play a key role in enhancing (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate production during starvation81 and moderating the steady-state ketogenic profile and is thought to be a consequence of the enhanced stored energy afforded by gut microbial SCFA production.27 Considering that (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate has recently been demonstrated as a potent HDACi,82 it remains to be seen whether it and other gut microbial-regulated serum metabolites capable of HDACi (i.e., butyrate, propionate and (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate) can alter brain development via its use as an energy source, HDACi or both.

Metabolite Sensing by G-Protein Coupled Receptors

Upon activation by an external ligand, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) initiate an intracellular signaling cascade resulting in a specific host cell response. Gut microbiota derived SCFAs acetate, propionate and butyrate activate host cell G-protein coupled receptors (i.e., GPR43 [FFAR2], GPR41 [FFAR3], and GPR109A[HM74a{human}/PUMA-G{mouse}]) with different potencies. Activation of GPR43 and GPR41 expressed beyond the colon mediate host immune responses83,84 and systemic metabolic regulation.85-88 Blood SCFA concentrations can serve as a useful proxy for determining the physiological concentrations of circulating SCFAs to which many cells throughout the body are exposed. Serum acetate (~50–1000 µM) and propionate (~5–150 µM) concentrations capable of GPR43 and GPR41 activation respectively, have been observed during fasting and dietary fiber manipulation.60-63,87,89 Serum butyrate concentrations observed after dietary fiber manipulation (1–5 µM)62 however, are unlikely to cause significant activation of GPR109a in peripheral organs.90 In peripheral tissue, GPR109a is activated by the ketone (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate which can reach as high as 6–8 mM during prolonged fasting.78 These observations indicate that under certain physiological conditions where colonic SCFA production is enhanced, or (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate production is increased, gut microbial-regulated metabolites in the circulation are capable of directly mediating effects on host cells via GPCR signaling.

Metabolite Sensors in the Sympathetic and Central Nervous System

GPCRs are major facilitators of neural transmission through their role as neurotransmitter receptors in both the sympathetic and central nervous system. The SCFA receptor GPR41 is highly expressed in the sympathetic ganglia91 and GPR109a expression has been demonstrated in the mammalian brain.92,93 GPR41, also known as the free fatty acid receptor 3, has been shown to play a key role in the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)91 including the regulation of blood pressure,94 likely through mediating the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (NE).95 In addition, (D)-3-hydroxybutyrate, a metabolite also subject to gut microbial regulation,27,81 was recently shown to antagonize GPR41-mediated SNS activation. Together, these observations demonstrate the potential for gut microbiota-regulated GPCR ligands in the blood to tweak neuronal activation of the SNS and potentially the central nervous system (CNS). A comprehensive characterization of SCFA receptor expression in the brain is needed to determine their relevance to direct CNS activation by gut microbial metabolites.

Gut Microbiota Dynamics during Brain Development

Pre and post-natal brain development is an intensely energy demanding process that progresses through distinct developmental windows.5,96 The period of increasing brain weight, referred to as the “brain growth spurt,” occurs at different times in different mammals.5 The human brain growth spurt occurs perinatally whereas rat the rat brain growth spurt occurs comparatively later during the postnatal period. This intensely energy demanding process is mainly attributed to glial cell proliferation and myelination.5

Human infant brain growth is accelerated in the months leading up to, and directly after birth97; a temporal neurodevelopmental window paralleled by major shifts in the maternal98 and infant microbiota composition.39-41 Comparisons between 1st and 3rd trimester microbiota compositions from humans revealed an increase in species of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria and an overall reduced microbial diversity.98 Interestingly, gut microbiota from the 3rd trimester exhibited a distinct metabolic phenotype capable of promoting greater energy storage compared with first trimester microbiota.98 This suggests an important role for the maternal microbiome in harvesting additional energy from the diet to sustain in utero infant development.

Postnatal neurodevelopment was examined using an animal model to compare Cesarean and vaginally delivered rats; two modes of delivery known to result in distinct microbial compositions.37 Using a rat model, reduced neuronal spine density in pre-frontal cortex (PFC) neurons and hippocampal pyramidal neurons at postnatal day 35 (P35), which were then normalized by P70, was observed in Caesarean born animals compared with vaginally born controls.99 Considering the likely differences in gut microbial colonization in this model, it will be interesting to elucidate whether these phenotypes are a consequence of differing microbial composition or colonization kinetics.

Gut Microbiota-Host Co-Metabolism and Brain Development

The role of the gut microbiome, and manipulations thereof, in modulating brain function has seen a recent flurry of detailed reviews.15,17,100-103 In particular, deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a pathway implicated in several neurological disorders including depression and anxiety, has been demonstrated in various models of gut microbial manipulation and generally appears to be overactive in the absence of gut microbiota.14,104-106 Pioneering work by Sudo and colleagues demonstrated that gut microbiota possess the capacity to modulate brain gene expression and that the HPA axis is programmed by microbial colonization during early-life.14 However, the causal factors mediating gut microbial activation of the HPA axis remain unclear. The HPA axis can be programmed by dietary conditions in early-life (recently reviewed in 106). As the diet is also a strong modulator of gut microbial composition and its metabolic output, it is therefore worth considering the contribution of gut microbial derived metabolites in setting the parameters for HPA axis activation.

A recent demonstration of the vital role for SCFA production in host development was demonstrated using germ-free Drosophila mono-associated with the commensal Acetobacter pomorum. This powerful model revealed the striking observation that the absence of Drosophila microbiota results in developmental arrest at the larval stage when exposed to nutrient limiting conditions. This phenotype could be rescued by monocolonisation with A. pomorum.12 This growth factor-like property of A. pomorum was shown to be indirectly related to the production of the SCFA acetate, which activated the insulin and/or insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) pathway. This remarkably thorough study clearly illustrates the fundamental importance of SCFA production by microbiota for invertebrate development, which may also be reflected in vertebrate development. Curiously, acetate production by A. pomorum was also implicated in the induced expression of Drosophila insulin-like peptides (DILPs) in the larval brain,12 a pathway analogous to the mammalian IIS pathway and implicated in Drosophila peripheral and CNS development.107 This demonstrates integration between microbial SCFA production and brain development.

Another microbial regulated metabolite relevant to brain development and function is tryptophan. Tryptophan is the metabolic precursor to the neurotransmitter serotonin, but unlike tryptophan, serotonin cannot cross the blood-brain-barrier and thus must be synthesized de novo in the brain from blood derived tryptophan. Thus, blood tryptophan provides the pool of available precursors for brain serotonin synthesis, which is modulated by gut microbiota.108,109 Indeed, we have demonstrated higher serotonin turnover in the striatum of germ-free mice compared with conventional counterparts.13 Others have recently demonstrated gut microbiota-dependent changes to the hippocampal serotonergic pathway in germ-free male mice, but not females.110 Considering the importance of serotonin for postnatal brain development,111 it will be of great interest to decipher the role of gut microbial tryptophan metabolism in this process.

Under nutrient limiting conditions, energy is rationed out to organs where it is most needed, with the brain and muscle taking priority. The cognitive cost of this process was recently demonstrated using Drosophila where memory formation was disabled during starvation.112 A germ-free mouse is somewhat reminiscent of a nutrient deprived animal as reflected by diminished fat stores,26 a more ketogenic profile under non-stressed conditions,27 lower serum glucose and metabolites available for ATP production.68 As memory consolidation is an energy demanding process,112 it will be of profound interest to determine whether this systemic scarcity of energy availability in germ-free mice is responsible for mediating impaired learning and memory observed in these mice.106 Furthermore, cognitive enhancement has also been observed in mice treated with the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1).105

In a recent study, Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1) was shown to alter GABA receptor expression in a brain region specific manner.105 This differential gene expression was associated with reduced anxiety-like behavior and reduced stress induced corticosterone production.105 Curiously, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treated mice also displayed enhanced memory to an aversive cue. An important outcome of this seminal work was that specific neurochemical and behavioral effects were not observed in vagotomised mice, thus implicating the vagus nerve as an important communication route between gut microbiota and the brain. Although anxiety-like behavior in this model was shown to be mediated via the vagus nerve, it remains to be determined whether L. rhamnosus (JB-1) enhances cognitive function via the same route, or whether these effects are mediated by metabolic signals from the blood stream.

Separately, L. rhamnosus has been shown to suppress diet induced obesity in mice.113 More recently, we demonstrated that Lactobacillus paracasei decreased fat storage and enhances serum very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) concentrations and serum levels of the lipoprotein lipase inhibitor, ANGPTL4.114 The ability of L. paracasei to induce ANGPTL4 expression in vitro was mediated by PPAR-γ and PPAR-α activation which may in part be attributed to the SCFA butyrate.115 Both L. rhamnosus and L. paracasei have been shown to modify gut microbiota composition and SCFA production which was correlated with altered hepatic lipid metabolism and circulating lipoprotein levels.116 It will be important to understand whether systemic metabolic changes that occur upon Lactobacilli administration are responsible for enhancing cognitive function, as was observed for L. rhamnosus (JB-1).105

Gut Microbial Modifications to Host Metabolism: Consequences for Brain Function

Gut microbiota have been implicated as major mediators of obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (T2D)117,118 (reviewed in ref. 4). Recently, insulin sensitivity was shown to be regulated via GPR43 activation by acetate.87 Furthermore, dietary administration of butyrate was shown to improve insulin sensitivity and enhance mitochondrial function in peripheral tissue.119 The brain is not entirely protected from metabolic disturbances and many of the molecular mediators of T2D, including insulin and leptin, have been associated with dementia120-122 (reviewed in refs. 123,124). In support of this, a T2D mouse model, characterized by poor insulin sensitivity, exhibited hippocampal dysfunction and plasticity.125 This phenotype could be ameliorated by maintaining normal physiological levels of corticosterone,125 a hormonal mediator of the HPA axis which has independently been shown to be regulated by gut microbiota.14,105

Leptin is another T2D relevant hormone subject to gut microbial regulation and plays a role in brain function.126,127 Leptin is a host derived hormone which acts as an appetite suppressant and is strongly implicated in obesity and T2D. In humans, higher levels of circulating leptin have been associated with a reduced risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease.128 In support of this, leptin has been shown to increase adult mouse hippocampal neurogenesis129 and rat hippocampal dendritic spine morphology.130 Interestingly, germ-free mice display low levels of circulating leptin126 and reduced cognitive function.106 Perhaps, lower levels of circulating leptin levels in germ-free mice126 reflect the lack of SCFA mediated GPR41 and/or GPR43 activation which has been shown to stimulate leptin production.131,132 It will therefore be of profound interest to delineate the mechanism of gut microbial leptin regulation and its implications for host metabolism and brain function.

Regarding behavior and cognition, diets designed to enhance gut microbial fiber fermentation in the colon have provided useful insight. Using dietary manipulations that enhance gut microbial fiber fermentation in the cecum and colon, a positive correlation was observed between lactic acid and volatile fatty acid (VFA) production with anxiety-like behavior and aggression.133 Subsequently, the same group demonstrated a positive correlation between serum lactate levels and the ability of rats to discriminate between a familiar and novel object,134 suggesting improved cognitive performance. These results suggest that cognitive function may be modified by enhancing gut microbial fiber fermentation efficiencies. Considering that SCFAs can cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB),135,136 it will be worthwhile determining whether SCFAs, and associated metabolites such as lactate, in peripheral circulation can mediate direct effects on cognition.

Microbial Behavior

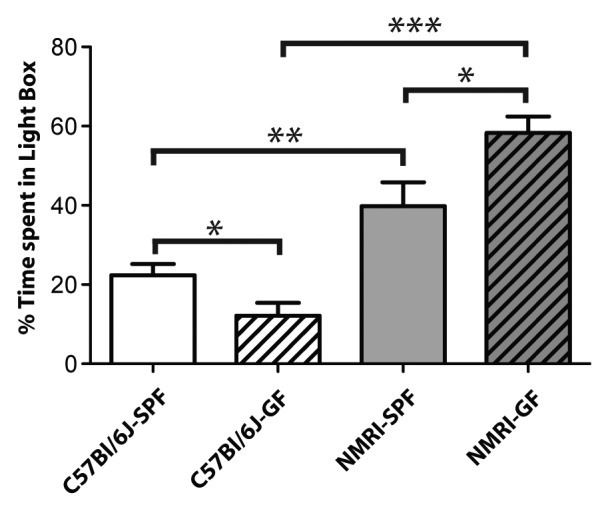

Different gut microbiota compositions have been shown to encode specific behavioral traits from inter-strain microbiota transplantation experiments.137 These authors exploited the inherent high anxiety-like behavior of BALB/c mice by comparing them to the less anxious NIH Swiss mouse strain. Microbiota transplants of BALB/c microbiota into germ-free NIH Swiss mice increased their anxiety-like behavior whereby the opposite was observed for the reverse transplantation into germ-free BALB/c mice. These data demonstrate that distinct gut microbiota compositions from individual mouse strains can impart behavioral functionality on the host. In support of these findings, we have also observed strain differences in relation to anxiety-like behavior when comparing germ-free NMRI and C57Bl6/J mice to conventionally raised specific pathogen free (SPF) counterparts (Fig. 4). This data supports previous observations that mouse strain specific differences in the gut microbiome composition can impose distinct behavioral characteristics and capable of either promoting or suppressing anxiety-like behavior.137 More research designed to exploit the inherent behavioral traits of laboratory animals may yield more interesting insight into the role of gut microbiota in anxiety-like behavior.

Figure 4. Strain differences in anxiety-like behavior between germ-free C57Bl/6J and NMRI mice. In the light-dark box test, a behavioral test for anxiety, mice were individually placed into a dark box and allowed 10 min of free exploration and the amount of time spent exploring the light box was recorded. An ANOVA showed significant main effects of strain of mice used and of being germ-free. Bonferroni-corrected t tests showed that within each strain, the C57Bl/6J and NMRI, the germ-free mice had significantly different anxiety-like behaviors from their SPF counterparts. Germ-free C57Bl/6J mice (n = 11) spent significantly less time exploring the light box compared with SPF counterparts (n = 14). NMRI germ-free mice (n = 5) spent significantly more time exploring the light box, and were significantly less anxious than their SPF counterparts (n = 7). P ≤ 0.05 (*), P ≤ 0.01 (**), P ≤ 0.001 (***).

An intriguing observation was recently made regarding the requirement of microbiota for social development in mice.138 In these experiments, germ-free mice exhibited reduced social motivation and preference for social novelty. Although social cognition appeared to be established in the pre-weaning phase of this model, the development of social avoidance may be subject to microbial disturbances in later life. These findings may have clinical relevance to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental brain disorder characterized by deficits in social interaction which has been associated with differences in gut microbiota composition.139 It remains to be addressed whether differences in gut microbiota composition139 or elevated faecal SCFA concentrations140 observed in individuals diagnosed with ASD, are correlative or causative differences of this disorder. In support of elevated SCFA production by gut microbes playing a role in ASD etiology, direct administration of propionate into the brains of rats has been shown to induce ASD-like behavior.141 Whether propionate overproduction by gut microbiota in ASD individuals can reach relevant concentrations in the human brain remains to be determined.

From an evolutionary perspective, host-host social interactions that are enhanced by gut microbiota will likely increase horizontal transfer of endogenous microbes between hosts. This is likely to be of benefit to the transferred microbe through increased access to novel niches and also to the host by enhancing resident microbial diversity, a property recently associated with significant benefits to host health.142,143 Thus, gut microbial promotion of physical interaction between individuals may impart significant fitness advantages to both host and microbe. Perhaps a gut microbiome with a reduced capacity to potentiate host-host social interactions manifest as social deficits associated with ASD.

Another remarkable demonstration of gut microbiota influencing host-host behavior was revealed in a seminal paper using Drosophila to illustrate principals of the hologenomic theory of evolution.144 Sharon and colleagues revealed that commensal microbiota are capable of inducing a preference in mate choice that persists for at least 37 generations.144 Although altered cuticular hydrocarbon regulation was implicated as a potential molecular correlate upon which mate scrutiny may be based, exactly how an individual perceives another individual as preferable over another in this model remains unclear and suggests a rewiring of neuronal circuitry and/or cognitive function. This raises the unexpected possibility that preferences in mate choice, at least in part, may be driven by the endogenous microbial composition of an individual host.

Conclusions

Gut microbiota manipulation in humans has recently been shown to modify human brain function,145 an observation which may instigate the tailoring of certain microbes to possible influence and attenuate certain psychiatric and cognitive disorders. This may prove to be a worthy pursuit for certain neurological mood disorders; however, neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders may be refractory to such interventions. Therefore, in depth profiling of the gut microbiome in a temporal and spatial manner as well as on individuals suffering various forms of human neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders is warranted, particularly those associated with metabolic and immune dysbiosis. To determine causation, germ-free animals reconstituted with microbiota from different developmental stages and diseased individuals, combined with robust paradigms to test relevant animal behavior, will be pivotal to deciphering the functional role of gut microbial variations in host brain development and later life function.

We hypothesize that environmental perturbations in gut microbiota composition will alter the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome which will result in changes in SCFA production. Consequently, this will ultimately impact on host organ development and function, including host brain development, via (1) changes in nutrient availability and (2) modifications in host transcription and cell function.

Similarly, we hypothesize that age associated changes in gut microbiota composition and concomitant changes in SCFA production,146 may also play an important role in mediating age associated cognitive decline, and potentially dementia progression. Deciphering the details of how the gut microbiome participates in early life brain development and later life function will be an important facet in understanding how the environment shapes neurological outcomes. Such detail will be essential to designing novel strategies to treat gut microbial disturbances and restore systemic metabolic harmony,147,148 an important underpinning of neurological health.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Song Hui Chng, Parag Kundu, and Gediminas Greicius for their valuable discussions and critical comments relating to this manuscript and Sze Ying for her involvement in animal handling and behavioral testing. This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (VR), Hjärnfonden, Lee Kong Chain School of Medicine Nanyang Technological University funds allocated to SP, the Singapore National Medical Research Council Translational and Clinical Research Program NMRC/TCR/003-GMS/2008 and Duke-NUS Block Funding.

References

- 1.Cummings JH. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon. Gut. 1981;22:763–79. doi: 10.1136/gut.22.9.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg E, Zilber-Rosenberg I. Symbiosis and development: the hologenome concept. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:56–66. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, Gill N, Blanchet MR, Mohn WW, McNagny KM, et al. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:440–7. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erecinska M, Cherian S, Silver IA. Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:397–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, van den Brandt PA, Stobberingh EE. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:511–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rautava S, Luoto R, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Microbial contact during pregnancy, intestinal colonization and human disease. Nature reviews. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:565–76. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martín R, Jiménez E, Heilig H, Fernández L, Marín ML, Zoetendal EG, Rodríguez JM. Isolation of bifidobacteria from breast milk and assessment of the bifidobacterial population by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and quantitative real-time PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:965–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02063-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward TL, Hosid S, Ioshikhes I, Altosaar I. Human milk metagenome: a functional capacity analysis. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martín R, Langa S, Reviriego C, Jimínez E, Marín ML, Xaus J, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM. Human milk is a source of lactic acid bacteria for the infant gut. J Pediatr. 2003;143:754–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semova I, Carten JD, Stombaugh J, Mackey LC, Knight R, Farber SA, Rawls JF. Microbiota regulate intestinal absorption and metabolism of fatty acids in the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:277–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, Kim B, Kim AC, Lee KA, Yoon JH, Ryu JH, Lee WJ. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Björkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3047–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, Sonoda J, Oyama N, Yu XN, Kubo C, Koga Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:263–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster JA, McVey Neufeld KA. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:305–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:735–42. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsythe P, Kunze WA. Voices from within: gut microbes and the CNS. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:55–69. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korosi A, Baram TZ. Plasticity of the stress response early in life: mechanisms and significance. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52:661–70. doi: 10.1002/dev.20490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monk C, Georgieff MK, Osterholm EA. Research review: maternal prenatal distress and poor nutrition - mutually influencing risk factors affecting infant neurocognitive development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:115–30. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herculano-Houzel S. Scaling of brain metabolism with a fixed energy budget per neuron: implications for neuronal activity, plasticity and evolution. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown AS, Susser ES. Prenatal nutritional deficiency and risk of adult schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1054–63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoek HW, Susser E, Buck KA, Lumey LH, Lin SP, Gorman JM. Schizoid personality disorder after prenatal exposure to famine. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1637–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neugebauer R, Hoek HW, Susser E. Prenatal exposure to wartime famine and development of antisocial personality disorder in early adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282:455–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown AS, van Os J, Driessens C, Hoek HW, Susser ES. Further evidence of relation between prenatal famine and major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:190–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajilić-Stojanović M, Smidt H, de Vos WM. Diversity of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota revisited. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2125–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mestdagh R, Dumas ME, Rezzi S, Kochhar S, Holmes E, Claus SP, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiota modulate the metabolism of brown adipose tissue in mice. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:620–30. doi: 10.1021/pr200938v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tennant B, Malm OJ, Horowitz RE, Levenson SM. Response of germfree, conventional, conventionalized and E. coli monocontaminated mice to starvation. J Nutr. 1968;94:151–60. doi: 10.1093/jn/94.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil NI. The contribution of the large intestine to energy supplies in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39:338–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(Suppl 2):S1–63. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P, Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:289–306. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shipman JA, Berleman JE, Salyers AA. Characterization of four outer membrane proteins involved in binding starch to the cell surface of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5365–72. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.19.5365-5372.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, Turnbaugh PJ, Fulton RS, Wollam A, Shah N, Wang C, Magrini V, Wilson RK, et al. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901529106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajslev TA, Andersen CS, Gamborg M, Sørensen TI, Jess T. Childhood overweight after establishment of the gut microbiota: the role of delivery mode, pre-pregnancy weight and early administration of antibiotics. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:522–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grönlund MM, Lehtonen OP, Eerola E, Kero P. Fecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: permanent changes in intestinal flora after cesarean delivery. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:19–25. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang C, Li S, Yang L, Huang P, Li W, Wang S, Zhao G, Zhang M, Pang X, Yan Z, et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota in life-long calorie-restricted mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2163. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mariat D, Firmesse O, Levenez F, Guimarăes V, Sokol H, Doré J, Corthier G, Furet JP. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkins MJ, Sharp R, Macfarlane GT. Variation in human intestinal microbiota with age. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34(Suppl 2):S12–8. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(02)80157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li JV, Ashrafian H, Bueter M, Kinross J, Sands C, le Roux CW, Bloom SR, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Marchesi JR, et al. Metabolic surgery profoundly influences gut microbial-host metabolic cross-talk. Gut. 2011;60:1214–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM, Jr., Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:78ra41. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.García-Ródenas CL, Bergonzelli GE, Nutten S, Schumann A, Cherbut C, Turini M, Ornstein K, Rochat F, Corthésy-Theulaz I. Nutritional approach to restore impaired intestinal barrier function and growth after neonatal stress in rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:16–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000226376.95623.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spencer SJ. Perinatal programming of neuroendocrine mechanisms connecting feeding behavior and stress. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:109. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kashyap PC, Marcobal A, Ursell LK, Larauche M, Duboc H, Earle KA, Sonnenburg ED, Ferreyra JA, Higginbottom SK, Million M, et al. Complex interactions among diet, gastrointestinal transit, and gut microbiota in humanized mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:967–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcobal A, Barboza M, Sonnenburg ED, Pudlo N, Martens EC, Desai P, Lebrilla CB, Weimer BC, Mills DA, German JB, et al. Bacteroides in the infant gut consume milk oligosaccharides via mucus-utilization pathways. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonnenburg ED, Zheng H, Joglekar P, Higginbottom SK, Firbank SJ, Bolam DN, Sonnenburg JL. Specificity of polysaccharide use in intestinal bacteroides species determines diet-induced microbiota alterations. Cell. 2010;141:1241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muegge BD, Kuczynski J, Knights D, Clemente JC, González A, Fontana L, Henrissat B, Knight R, Gordon JI. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science. 2011;332:970–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1198719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, Sun W, O’Connell TM, Bunger MK, Bultman SJ. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergman EN. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:567–90. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bugaut M. Occurrence, absorption and metabolism of short chain fatty acids in the digestive tract of mammals. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1987;86:439–72. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marty J, Vernay M. Absorption and metabolism of the volatile fatty acids in the hind-gut of the rabbit. Br J Nutr. 1984;51:265–77. doi: 10.1079/BJN19840031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Cummings JH. Carbohydrate fermentation in the human colon and its relation to acetate concentrations in venous blood. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1448–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI111847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scheppach W, Pomare EW, Elia M, Cummings JH. The contribution of the large intestine to blood acetate in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991;80:177–82. doi: 10.1042/cs0800177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolever TM, Chiasson JL. Acarbose raises serum butyrate in human subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tarini J, Wolever TM. The fermentable fibre inulin increases postprandial serum short-chain fatty acids and reduces free-fatty acids and ghrelin in healthy subjects. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:9–16. doi: 10.1139/H09-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Priebe MG, Wang H, Weening D, Schepers M, Preston T, Vonk RJ. Factors related to colonic fermentation of nondigestible carbohydrates of a previous evening meal increase tissue glucose uptake and moderate glucose-associated inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:90–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sealy L, Chalkley R. The effect of sodium butyrate on histone modification. Cell. 1978;14:115–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Candido EP, Reeves R, Davie JR. Sodium butyrate inhibits histone deacetylation in cultured cells. Cell. 1978;14:105–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Velagapudi VR, Hezaveh R, Reigstad CS, Gopalacharyulu P, Yetukuri L, Islam S, Felin J, Perkins R, Borén J, Oresic M, et al. The gut microbiota modulates host energy and lipid metabolism in mice. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1101–12. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang N, Yan X, Zhou W, Zhang Q, Chen H, Zhang Y, Zhang X. NMR-based metabonomic investigations into the metabolic profile of the senescence-accelerated mouse. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:3678–86. doi: 10.1021/pr800439b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peleg S, Sananbenesi F, Zovoilis A, Burkhardt S, Bahari-Javan S, Agis-Balboa RC, Cota P, Wittnam JL, Gogol-Doering A, Opitz L, et al. Altered histone acetylation is associated with age-dependent memory impairment in mice. Science. 2010;328:753–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1186088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah P, Nankova BB, Parab S, La Gamma EF. Short chain fatty acids induce TH gene expression via ERK-dependent phosphorylation of CREB protein. Brain Res. 2006;1107:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DeCastro M, Nankova BB, Shah P, Patel P, Mally PV, Mishra R, La Gamma EF. Short chain fatty acids regulate tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression through a cAMP-dependent signaling pathway. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;142:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Wang X, Dobbin M, Tsai LH. Recovery of learning and memory is associated with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2007;447:178–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kilgore M, Miller CA, Fass DM, Hennig KM, Haggarty SJ, Sweatt JD, Rumbaugh G. Inhibitors of class 1 histone deacetylases reverse contextual memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:870–80. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrante RJ, Kubilus JK, Lee J, Ryu H, Beesen A, Zucker B, Smith K, Kowall NW, Ratan RR, Luthi-Carter R, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition by sodium butyrate chemotherapy ameliorates the neurodegenerative phenotype in Huntington’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9418–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09418.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Metabolism of short-chain fatty acids by rat colonic mucosa in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G31–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.1.G31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cotter DG, Ercal B, d’Avignon DA, Dietzen DJ, Crawford PA. Impact of peripheral ketolytic deficiency on hepatic ketogenesis and gluconeogenesis during the transition to birth. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19739–49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cahill GF., Jr. Fuel metabolism in starvation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nehlig A. Brain uptake and metabolism of ketone bodies in animal models. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:265–75. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cahill GF., Jr. Starvation in man. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:668–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197003192821209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Crawford PA, Crowley JR, Sambandam N, Muegge BD, Costello EK, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Regulation of myocardial ketone body metabolism by the gut microbiota during nutrient deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11276–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902366106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W, Shirakawa K, Le Moan N, Grueter CA, Lim H, Saunders LR, Stevens RD, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339:211–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1227166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, Schilter HC, Rolph MS, Mackay F, Artis D, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Macia L, Thorburn AN, Binge LC, Marino E, Rogers KE, Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Kranich J, Mackay CR. Microbial influences on epithelial integrity and immune function as a basis for inflammatory diseases. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:164–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, Parker HE, Habib AM, Diakogiannaki E, Cameron J, Grosse J, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes. 2012;61:364–71. doi: 10.2337/db11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, Hammer RE, Williams SC, Crowley J, Yanagisawa M, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kimura I, Ozawa K, Inoue D, Imamura T, Kimura K, Maeda T, Terasawa K, Kashihara D, Hirano K, Tani T, et al. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bellahcene M, O’Dowd JF, Wargent ET, Zaibi MS, Hislop DC, Ngala RA, Smith DM, Cawthorne MA, Stocker CJ, Arch JR. Male mice that lack the G-protein-coupled receptor GPR41 have low energy expenditure and increased body fat content. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1755–64. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peters SG, Pomare EW, Fisher CA. Portal and peripheral blood short chain fatty acid concentrations after caecal lactulose instillation at surgery. Gut. 1992;33:1249–52. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, Ananth S, Gnanaprakasam JP, Browning DD, Mellinger JD, Smith SB, Digby GJ, Lambert NA, et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2826–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kimura I, Inoue D, Maeda T, Hara T, Ichimura A, Miyauchi S, Kobayashi M, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G. Short-chain fatty acids and ketones directly regulate sympathetic nervous system via G protein-coupled receptor 41 (GPR41) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Titgemeyer EC, Mamedova LK, Spivey KS, Farney JK, Bradford BJ. An unusual distribution of the niacin receptor in cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94:4962–7. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller CL, Dulay JR. The high-affinity niacin receptor HM74A is decreased in the anterior cingulate cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, Peterlin Z, Sipos A, Han J, Brunet I, Wan LX, Rey F, Wang T, et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Inoue D, Kimura I, Wakabayashi M, Tsumoto H, Ozawa K, Hara T, Takei Y, Hirasawa A, Ishihama Y, Tsujimoto G. Short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR41-mediated activation of sympathetic neurons involves synapsin 2b phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Andersen SL. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, Gonzalez A, Werner JJ, Angenent LT, Knight R, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150:470–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Juárez I, Gratton A, Flores G. Ontogeny of altered dendritic morphology in the rat prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens following Cesarean delivery and birth anoxia. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1734–47. doi: 10.1002/cne.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:713–9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grenham S, Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Brain-gut-microbe communication in health and disease. Front Physiol. 2011;2:94. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saulnier DM, Ringel Y, Heyman MB, Foster JA, Bercik P, Shulman RJ, Versalovic J, Verdu EF, Dinan TG, Hecht G, et al. The intestinal microbiome, probiotics and prebiotics in neurogastroenterology. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:17–27. doi: 10.4161/gmic.22973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:255–64, e119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gareau MG, Wine E, Rodrigues DM, Cho JH, Whary MT, Philpott DJ, Macqueen G, Sherman PM. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60:307–17. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fernandez R, Tabarini D, Azpiazu N, Frasch M, Schlessinger J. The Drosophila insulin receptor homolog: a gene essential for embryonic development encodes two receptor isoforms with different signaling potential. EMBO J. 1995;14:3373–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wikoff WR, Anfora AT, Liu J, Schultz PG, Lesley SA, Peters EC, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics analysis reveals large effects of gut microflora on mammalian blood metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812874106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sjögren K, Engdahl C, Henning P, Lerner UH, Tremaroli V, Lagerquist MK, Bäckhed F, Ohlsson C. The gut microbiota regulates bone mass in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1357–67. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:666–73. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Migliarini S, Pacini G, Pelosi B, Lunardi G, Pasqualetti M. Lack of brain serotonin affects postnatal development and serotonergic neuronal circuitry formation. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:1106–18. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Plaçais PY, Preat T. To favor survival under food shortage, the brain disables costly memory. Science. 2013;339:440–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1226018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lee HY, Park JH, Seok SH, Baek MW, Kim DJ, Lee KE, Paek KS, Lee Y, Park JH. Human originated bacteria, Lactobacillus rhamnosus PL60, produce conjugated linoleic acid and show anti-obesity effects in diet-induced obese mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:736–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Aronsson L, Huang Y, Parini P, Korach-André M, Håkansson J, Gustafsson JA, Pettersson S, Arulampalam V, Rafter J. Decreased fat storage by Lactobacillus paracasei is associated with increased levels of angiopoietin-like 4 protein (ANGPTL4) PLoS One. 2010;5:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Korecka A, de Wouters T, Cultrone A, Lapaque N, Pettersson S, Doré J, Blottière HM, Arulampalam V. ANGPTL4 expression induced by butyrate and rosiglitazone in human intestinal epithelial cells utilizes independent pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G1025–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00293.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martin FP, Wang Y, Sprenger N, Yap IK, Lundstedt T, Lek P, Rezzi S, Ramadan Z, van Bladeren P, Fay LB, et al. Probiotic modulation of symbiotic gut microbial-host metabolic interactions in a humanized microbiome mouse model. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:157. doi: 10.1038/msb4100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, Liang S, Zhang W, Guan Y, Shen D, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Amar J, Chabo C, Waget A, Klopp P, Vachoux C, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Smirnova N, Bergé M, Sulpice T, Lahtinen S, et al. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:559–72. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, Cefalu WT, Ye J. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1509–17. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ramos-Rodriguez JJ, Ortiz O, Jimenez-Palomares M, Kay KR, Berrocoso E, Murillo-Carretero MI, Perdomo G, Spires-Jones T, Cozar-Castellano I, Lechuga-Sancho AM, et al. Differential central pathology and cognitive impairment in pre-diabetic and diabetic mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2462–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Awad N, Gagnon M, Messier C. The relationship between impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive function. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:1044–80. doi: 10.1080/13803390490514875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease--is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stranahan AM, Mattson MP. Bidirectional metabolic regulation of neurocognitive function. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:507–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:45–61. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stranahan AM, Arumugam TV, Cutler RG, Lee K, Egan JM, Mattson MP. Diabetes impairs hippocampal function through glucocorticoid-mediated effects on new and mature neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:309–17. doi: 10.1038/nn2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schéle E, Grahnemo L, Anesten F, Hallén A, Bäckhed F, Jansson JO. The gut microbiota reduces leptin sensitivity and the expression of the obesity-suppressing neuropeptides proglucagon (Gcg) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf) in the central nervous system. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3643–51. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gauffin Cano P, Santacruz A, Moya Á, Sanz Y. Bacteroides uniformis CECT 7771 ameliorates metabolic and immunological dysfunction in mice with high-fat-diet induced obesity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lieb W, Beiser AS, Vasan RS, Tan ZS, Au R, Harris TB, Roubenoff R, Auerbach S, DeCarli C, Wolf PA, et al. Association of plasma leptin levels with incident Alzheimer disease and MRI measures of brain aging. JAMA. 2009;302:2565–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Garza JC, Guo M, Zhang W, Lu XY. Leptin increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18238–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800053200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.O’Malley D, MacDonald N, Mizielinska S, Connolly CN, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin promotes rapid dynamic changes in hippocampal dendritic morphology. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:559–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Xiong Y, Miyamoto N, Shibata K, Valasek MA, Motoike T, Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate leptin production in adipocytes through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1045–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hong YH, Nishimura Y, Hishikawa D, Tsuzuki H, Miyahara H, Gotoh C, Choi KC, Feng DD, Chen C, Lee HG, et al. Acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids stimulate adipogenesis via GPCR43. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5092–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hanstock TL, Clayton EH, Li KM, Mallet PE. Anxiety and aggression associated with the fermentation of carbohydrates in the hindgut of rats. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:357–68. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hanstock TL, Mallet PE, Clayton EH. Increased plasma d-lactic acid associated with impaired memory in rats. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:653–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Conn AR, Fell DI, Steele RD. Characterization of alpha-keto acid transport across blood-brain barrier in rats. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:E253–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.245.3.E253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Patel AB, de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Shulman RG, Behar KL. The contribution of GABA to glutamate/glutamine cycling and energy metabolism in the rat cortex in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501703102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, Jackson W, Lu J, Jury J, Deng Y, Blennerhassett P, Macri J, McCoy KD, et al. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:599–609, e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota is essential for social development in the mouse. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:146–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kang DW, Park JG, Ilhan ZE, Wallstrom G, Labaer J, Adams JB, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Reduced incidence of Prevotella and other fermenters in intestinal microflora of autistic children. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wang L, Christophersen CT, Sorich MJ, Gerber JP, Angley MT, Conlon MA. Elevated fecal short chain fatty acid and ammonia concentrations in children with autism spectrum disorder. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2096–102. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.MacFabe DF, Cain DP, Rodriguez-Capote K, Franklin AE, Hoffman JE, Boon F, Taylor AR, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP. Neurobiological effects of intraventricular propionic acid in rats: possible role of short chain fatty acids on the pathogenesis and characteristics of autism spectrum disorders. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:149–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto JM, Kennedy S, et al. MetaHIT consortium Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500:541–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Cotillard A, Kennedy SP, Kong LC, Prifti E, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, Almeida M, Quinquis B, Levenez F, Galleron N, et al. ANR MicroObes consortium Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature. 2013;500:585–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sharon G, Segal D, Ringo JM, Hefetz A, Zilber-Rosenberg I, Rosenberg E. Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009906107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Guyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1394–401, e1-4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, Harris HM, Coakley M, Lakshminarayanan B, O’Sullivan O, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178–84. doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Holmes E, Kinross J, Gibson GR, Burcelin R, Jia W, Pettersson S, Nicholson JK. Therapeutic modulation of microbiota-host metabolic interactions. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:rv6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]