Abstract

Strongyloidiasis is infection caused by the nematode Strongyloides stercoralis. Chronic uncomplicated strongyloidiasis is known to occur in immunocompetent individuals while hyperinfection and dissemination occurs in selective immunosuppressed hosts particularly those on corticosteroid therapy. We report two cases of hyperinfection strongyloidiasis in renal transplant recipients and document endoscopic and pathological changes in the involved small bowel. One patient presented with features of dehydration and malnutrition while another developed ileal obstruction and strangulation, requiring bowel resection. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed erythematous and thickened duodenal mucosal folds. Histopathological examination of duodenal biopsies revealed S. stercoralis worms, larvae and eggs embedded in mucosa and submucosa. Wet mount stool preparation showed filariform larvae of S. stercoralis in both cases. Patients were managed with anthelmintic therapy (ivermectin/albendazole) and concurrent reduction of immunosuppression. Both patients had uneventful recovery. Complicated strongyloidiasis should be suspected in immunocompromised hosts who present with abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea, particularly in endemic areas.

Background

Strongyloidiasis, caused by Strongyloides stercoralis is the fourth most common nematode infection. The disease is estimated to affect 100 to 200 million people worldwide. S. stercoralis is predominantly a problem of humid tropical areas. High-endemic zones of the world include India, Argentina, Brazil, Peru and other tropical areas of the world. However, cases have also been reported from the USA, Japan and Australia.1 2

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex and follows multiple routes. The parasite has the ability to complete its life cycle outside the human host. Adult male and female (free living) worms live in soil and lay eggs that hatch into rhabditiform larvae. Rhabditiform larvae develop in the soil into mature adults to complete the life cycle of the worm. Human infection occurs when the infective filariform larvae penetrate any area of skin that contacts the soil, after which they migrate through the dermis to enter the vasculature. The larvae reach the lungs, break into the alveoli and ascend up along the bronchial tree into the throat and are swallowed with saliva. The larvae develop into parthenogenetic adult females (approximately 2.2–2.5 mm long and 50 µm in diameter). The female worms penetrate the gut wall and lodge in the lamina propria of the duodenum and jejunum. The worms lay eggs that hatch within the gut wall and rhabditiform larvae migrate into the lumen and are passed with the stools. Autoinfection is known to occur with S. stercoralis. The rhabditiform larvae develop into filariform larvae within the intestines, which may penetrate the colonic wall or perianal skin and complete an internal cycle (autoinfection), thereby increasing the parasite burden. The phenomenon of autoinfection has important clinical implications, as this process is responsible for the persistence of infection virtually indefinitely in infected hosts.3 4

Autoinfection is believed to be regulated by host immunity.5–7 In an immunocompetent host, infection with S. stercoralis produces a negligible or minimally symptomatic chronic disease. When immunosuppression impairs the host's regulatory function, increasing numbers of autoinfective larvae complete the cycle and the population of parasitic adult worms increases (hyperinfection). This leads to locally destructive bowel or lung disease. In disseminated strongyloidiasis extraordinary numbers of larvae deviate from the canonical route (intestine-venous circulation-lungs-trachea-intestine) and disseminate to other organs, namely brain, meningeal spaces, liver, kidneys, lymph nodes, cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues.4 8

Many case reports and series of strongyloidiasis have been reported from endemic areas of the world.2 However, there is paucity of documentation of endoscopic, gross and histological findings. Here, we report two cases of S. stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome from North India and document their endoscopic and pathological findings.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 32-year-old woman with cryptogenic end-stage renal disease, had been on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis for 3 years. She received a cadaveric renal transplant. Post-transplant she was on triple immunosuppression, which included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone. A protocol renal biopsy at 3 months revealed normal renal tissue. She was maintained on tacrolimus 1 mg orally twice daily, mycophenolate mofetil 1 g orally twice daily and prednisolone 5 mg orally once daily. She was apparently well for the next 10 months. She presented with epigastric pain, recurrent vomiting and progressive weight loss of 20 kg over a 2-month period and had made multiple emergency room visits with no relief of symptoms. She denied history of haematemesis, melena, haematochezia, fever, cough, expectoration or haemoptysis. On examination she was weak, asthenic and emaciated. Vitals included pulse 140/min, blood pressure 93 mm Hg systolic and 58 mm Hg diastolic, temperature 37.3°C and SpO2 95%. Her abdomen examination was normal apart from a palpable transplanted kidney in the right iliac fossa.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman received a cadaveric renal transplant for end-stage renal disease caused by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Prior to receiving renal transplant she was on regular haemodialysis for 5 years. Post-transplant she was on triple immunosuppressive therapy including tacrolimus 2 mg orally twice daily, mycophenolate mofetil 1 g orally twice daily and prednisolone 12.5 mg orally once daily. She did well and her renal functions returned to normal on the seventh postoperative day. Three months following the transplant, she developed acute abdominal pain, distension and vomiting and was admitted to the emergency room. She denied history of haematemesis, melena, fever, cough, haemoptysis, jaundice or skin rashes. Vitals included pulse 120/min, blood pressure 120 mm Hg systolic and 80 mm Hg diastolic, temperature 37°C and SpO2 90%. Physical examination revealed diffuse abdominal distension, tenderness and increased bowel sounds. A diagnosis of intestinal obstruction was suspected.

Investigations

Case 1

Complete blood counts revealed: haemoglobin 10.2 g/dL (normal 13.8–17.2 g/dL), white cell count 11.4×103/mm3 (normal 4–11×103/mm3) and platelet count 437×103/mm3 (normal 150–400×103/mm3). Differential leucocyte counts were: segmented neutrophils 60% (normal 40–80%), lymphocytes 30% (normal 20–40%) and eosinophils 10% (normal 1–6%). Serum chemistry revealed: albumin 2.7 g/dL (normal 3.2–4.6 g/dL), bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL (normal 0.3–1.3 mg/dL), creatinine 1.2 mg/dL (normal 0.5–0.9 mg/dL), sodium 130 mEq/L (normal 136–146 mEq/L) and potassium 4.7 mEq/L (normal 3.5–5.1 mEq/L). Blood tacrolimus (trough) levels were 6 ng/mL (therapeutic levels 1 year post-transplant: 5–10 ng/mL). She was negative for hepatitis B surface antigen, antibodies to hepatitis C virus, HIV-1 and HIV-2. Video oesophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed mild erythematous exudative gastritis in the gastric antrum, and erythematous bulbar and postbulbar duodenitis (figure 1A, B). Endoscopic punch forceps biopsies of the abnormal duodenal mucosa were obtained. Histopathological examination revealed larvae and eggs of S. stercoralis in the duodenal mucosa and submucosa. There was infiltration by mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils and monocytes (figure 2B, C). Wet mount stool preparation revealed filariform larvae of S. stercoralis. The larvae were long and slender measuring 500–550 µm in length (figure 2A). A diagnosis of S. stercoralis hyperinfection presenting with malnutrition, dehydration, anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia was made.

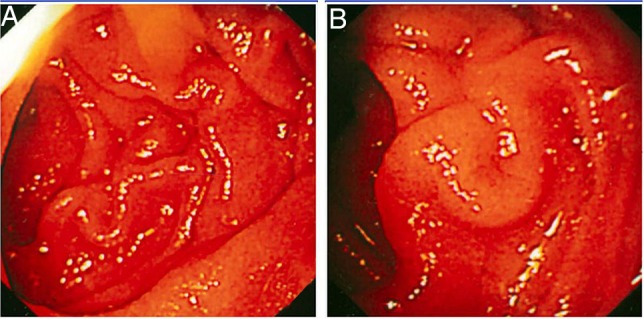

Figure 1.

(A and B) Case 1. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. Both images show erythematous and thickened mucosal folds in second part of duodenum.

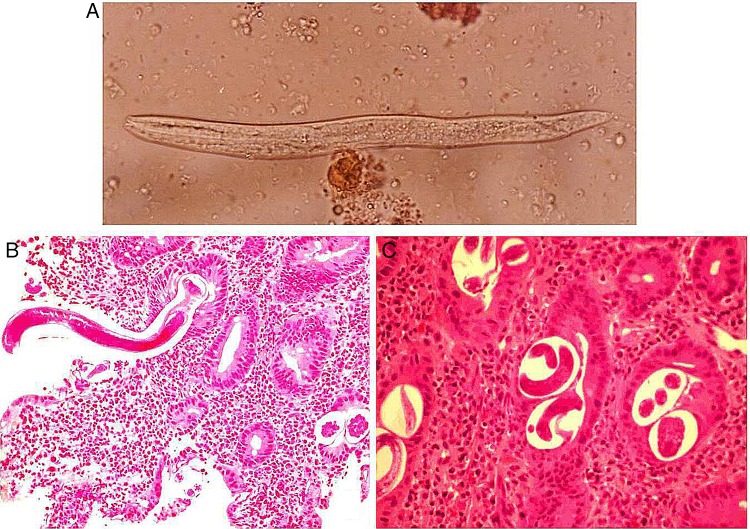

Figure 2.

(A) Case 1. Wet mount stool showing filariform larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis. Detection of S. stercoralis larvae in stool specimens is usually easier in cases of hyperinfection, due to large worm burdens as compared to specimens from immunocompetent hosts. (B) Longitudinal sections of larvae of S. Stercoralis embedded in duodenal mucosa surrounded by mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils (×200). (C) Duodenal biopsy section showing cross-section of embryonated eggs of S. stercoralis in lamina propria surrounded by inflammation (×400).

Case 2

Complete blood counts revealed: haemoglobin 9 g/dL (normal 13.8–17.2 g/dL), white cell count 24×103/mm3 (normal 4–11×103/mm3) and platelet count 380×103/mm3 (normal 150–400×103/mm3). Differential leucocyte counts were: segmented neutrophils 85% (normal 40–80%), lymphocytes 10% (normal 20–40%) and eosinophils 5% (normal 1–6%). Serum chemistry revealed: albumin 4 g/dL (normal 3.2–4.6 g/dL), bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL (normal 0.3–1.3 mg/dL), creatinine 1.7 mg/dL (normal 0.5–0.9 mg/dL), sodium 128 mEq/L (normal 136–146 mEq/L) and potassium 3.5 mEq/L (normal 3.5–5.1 mEq/L). Blood tacrolimus (trough) levels were 15 ng/mL (therapeutic levels 3 months post-transplant: 12–19 ng/mL). Blood cultures were sterile for aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Plain X-ray abdomen showed a markedly distended small bowel loop with large air fluid levels (figure 3A). Video oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed normal examination of oesophagus, stomach and duodenal bulb. The second part of the duodenum showed markedly erythematous and thickened mucosal folds with erosions (figure 3B, C). Endoscopic punch forceps biopsies were obtained from the duodenal mucosa. Histopathological examination of the biopsies revealed larvae of S. stercoralis embedded in the mucosa. Wet mount stool preparation revealed filariform larvae of S. stercoralis. A diagnosis of S. stercoralis hyperinfection presenting with intestinal obstruction and sepsis was entertained.

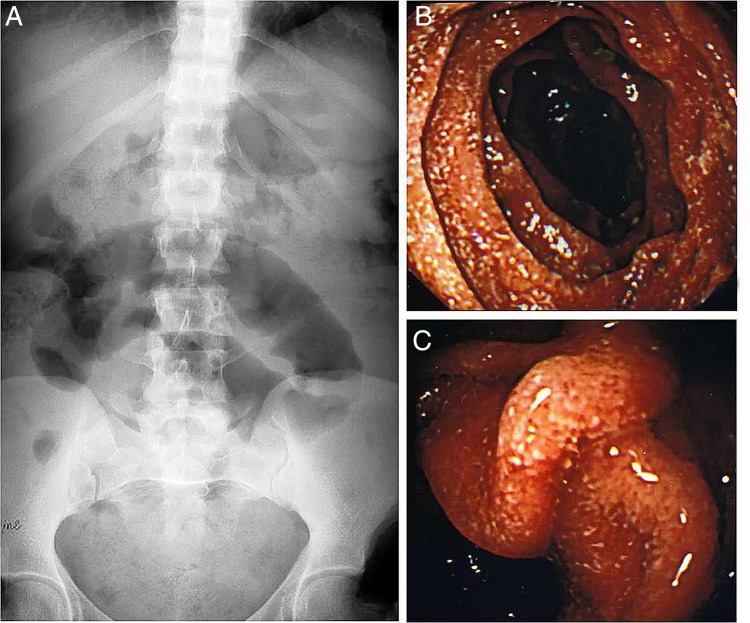

Figure 3.

(A) Case 2. Plain X-ray film of the abdomen showing a single dilated small bowel loop. (B and C) Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. The images show erythematous thickened mucosal folds with erosions and granularity in the second part of the duodenum.

Treatment

Case 1

The patient received hydration and nutritional support. She was treated with albendazole 400 mg orally for 3 days followed by ivermectin 3 mg orally once daily for 3 days. Mycophenolate mofetil dosage was reduced to 500 mg orally thrice per day (tacrolimus and prednisolone dosage was maintained). Over the next 1 month she had rapid relief of abdominal pain, stopped vomiting and gained weight of 5 kg.

Case 2

The patient was managed with nasogastric suction, intravenous fluids, broad-cover antibiotics and analgaesics. Immunosuppression was reduced to tacrolimus 1 mg orally twice daily, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg orally thrice daily and prednisolone 10 mg orally once daily. Ivermectin 3 mg was administered through the nasogastric tube for 3 days. She continued to have signs of bowel obstruction and developed early signs of bowel ischaemia as evidenced by progressive abdominal distension and sluggish bowel sounds. An emergency laparotomy revealed thickened and non-viable distal small bowel (15 cm), which was resected with end-to-end anastomosis. Resected bowel showed extensive mucosal ulceration, oedema and thickened bowel wall (figure 4A). Histopathological examination revealed an abundance of S. stercoralis worms, larvae and embryonated eggs in the bowel wall (figure 4B, C). In addition, the bowel mucosa showed features of catarrhal exudate and mucosal and submucosal infarction (figure 4C). Lymph nodes of the resected specimen revealed parasites in subcapsular spaces with features of reactive lymphadenitis (figure 4D). Following surgery the patient received ivermectin 6 mg as retention enema twice daily for 3 days.

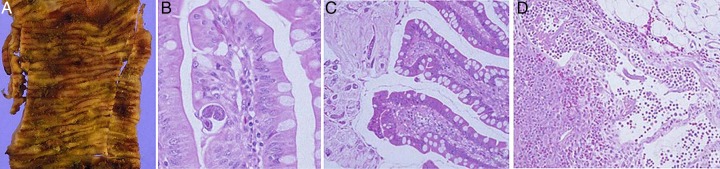

Figure 4.

Case 2. Resected ileal specimen (A) Gross appearance. Markedly congested, granular mucosa with multiple areas of ulceration and haemorrhage. (B) Light microscopy. Section of Strongyloides stercoralis worm in lamina propria. There is moderate inflammation in vicinity of the parasite (H&E ×400). (C) Light microscopy. S. stercoralis worms are seen embedded in the luminal mucus overlying the mucosa of the small bowel. Abundant mucoid secretions are noted (‘Catarrhal enteritis’; H&E ×200). (D) Light microscopy lymph node. A wandering worm of S. stercoralis is seen in the subcapsular sinus of the lymph node (H&E ×200).

Outcome and follow-up

Case 1

Follow-up video of the oesophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a normal stomach and duodenal mucosa and repeat punch forceps biopsies did not reveal S. stercoralis in the tissue. The patient has stayed well on follow-up for 3 years.

Case 2

The patient made an uneventful recovery and has been on regular follow-up for 2 years following surgery.

Discussion

The two cases of S. stercoralis reported here occurred in patients with renal transplant under immunosuppression. Hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis can ensue in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity (such as patients with transplant, patients receiving steroids or immunosuppressive therapy or patients infected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1).9 10 Patients with HIV and acquired immunoglobulinopathies and immune deficiencies do not usually predispose to hyperinfection or dissemination even in hyperendemic areas for unknown reasons. However, hyperinfection has been reported in patients with HIV who are on concomitant steroid therapy.11 Recent reports of transmission of strongyloidiasis with the transplanted organ from an infected donor are also on record. The patients have been eventually reported to develop hyperinfection.12

Case 1 had features of hyperinfection syndrome with abundance of worms localised in the duodenum along with evidence of duodenitis. She had subacute presentation simulating malabsorption syndrome. In addition, she was dehydrated as a result of recurrent vomiting. Reported gastrointestinal manifestations of hyperinfection syndrome include epigastric pain, bloating, heartburn and altered bowel habits. Gastrointestinal bleeding has been reported and some patients present with features resembling inflammatory bowel disease.13–15 Malabsorption has also been reported, however, a clear causal relationship between S. stercoralis infection and malabsorption in otherwise healthy participants has not been established.4 Case 2 had early features of disseminated strongyloidiasis as lymph nodes of the resected specimen revealed wandering parasites in subcapsular space outside the canonical route of the parasite. This patient presented with acute intestinal obstruction resulting in bowel ischaemia. These patients may, in addition, develop polymicrobial, predominantly Gram-negative septicaemia as a consequence of extensive erosions, ulceration and oedema of the bowel as well as migration of microbes on their cuticles to distant sites.16 Reported gastrointestinal manifestations of disseminated strongyloidiasis are almost invariably serious and include profuse diarrhoea, paralytic ileus and intra-abdominal abscesses.4

Endoscopic findings in both our patients revealed erythematous, thickened mucosal folds in the second part of the duodenum. Case 2, in addition, had erosions and granular mucosa. Similar duodenoscopy findings have been reported in the literature.14 Some studies have revealed endoscopic findings resembling inflammatory bowel disease including pseudopolyposis.13

Chronic uncomplicated strongyloidiasis has been reported in immunocompetent hosts. Such patients have minimal gut worm burden. The worms and larvae inhabit the intestinal mucosa without causing significant inflammatory response or tissue damage.17 18 The hyperinfection syndrome has been reported in selective immunocompromised hosts. The gut worm burden in such patients is markedly increased and there are associated pathological changes including oedema, erosions, ulceration, fibrosis and atrophy. This can lead to catarrhal, oedematous and ulcerative enteritis. Jejunal perforation, eosinophilic colitis and pseudopolyposis is known to occur.14 17 18 Mucosal changes similar to those seen in coeliac disease, including villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia, have also been reported.19 In disseminated infections, hundreds and thousands of parasites dwell in the intestine and migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes, biliary tract, liver, spleen, heart, endocrine organs and ovaries. Disseminated S. stercoralis infections causes target organ damage, leading to serious and life-threatening disease manifestations.2 4 16 In case 2, presence of filariform larvae in the lymph node suggested early signs of disseminated strongyloidiasis.

We managed our patients by anthelmintic therapy and concurrent reduction in immunosuppressive therapy. Case 1 received a combination of albendazole and ivermectin therapy. Albendazole is a broad spectrum anthelmintic with variable therapeutic efficacy.4 It is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and has a cure rate of 36–75% in strongyloidiasis. Ivermectin is a broad spectrum anthelminthic and is the drug of choice in treatment of intestinal and disseminated strongyloidiasis. Ivermectin has a cure rate of 64–100% after a single dose.20 Immunosuppressed patients, patients with disseminated disease or hyperinfection syndrome need therapy for 3–7 days or repeat dosage. Ivermectin administered as an enema (as in case 2) is of benefit in patients with severe strongyloidiasis who are unable to absorb the drug due to bowel obstruction.4

Learning points.

Appropriate methods of human faecal sanitation, sewage disposal and personal hygiene are of paramount importance in controlling infection in endemic areas.

Immunocompromised patients after solid organ transplant and patients on steroid therapy need to be monitored and kept on follow-up for opportunistic infections, including parasitic infections. Strongyloidiasis should be suspected when such patients present with abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhoea, particularly in endemic zones.

Diagnosis of strongyloidiasis can be established by stool examination for larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis and endoscopic punch forceps biopsies of duodenal mucosa.

Strongyloides hyper infection can be fatal in the absence of timely intervention.

In addition to stool examination, endoscopic surveillance followed by biopsy confirmation is crucial for early diagnosis and intervention.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of Prof Mohammad Sultan Khuroo (Director, Digestive Diseases Centre) and Dr Naira Sultan Khuroo (Consultant Radiologist), Dr Khuroo's Medical Clinic, Srinagar, J&K for the endoscopic and radiological images.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1411–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, et al. Severe strongyloidiasis: a systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segarra-Newnham M. Manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui AA, Genta RM, Maguilnik I, et al. Strongyloidiasis. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, eds Tropical infectious siseases: principles, pathogens & practice. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2011:805–12 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genta RM. Immunobiology of strongyloidiasis. Trop Geogr Med 1984; 36:223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Igra-Siegman Y, Kapila R, Sen P, et al. Syndrome of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis. Rev Infect Dis 1981;3:397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganesh S, Cruz RJ., Jr Strongyloidiasis: a multifaceted disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:194–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhury DN, Dhadham GC, Shah A, et al. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) in Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection. J Glob Infect Dis 2014;6:23–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffer MW, Buell JF, Gupta M, et al. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004;23:905–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grover IS, Davila R, Subramony C, et al. Strongyloides infection in a cardiac transplant recipient: making a case for pretransplantation screening and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:763–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mascarello M, Gobbi F, Angheben A, et al. Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection among HIV-positive immigrants attending two Italian hospitals from 2000–2009. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2011;105:617–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roseman DA, Kabbani D, Kwah J, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis transmission by kidney transplantation in two recipients from a common donor. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2483–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carp NZ, Nejman JH, Kelly JJ. Strongyloidiasis. An unusual cause of colonic pseudopolyposis and gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Endosc 1987;1:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishimoto K, Hokama A, Hirataet T, et al. Endoscopic and histopathological study on the duodenum of Strongyloides Stercoralis hyperinfection. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:1768–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Samman M, Haque S, Long JD. Strongyloidiasis colitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;28:77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasih N, Irfan S, Sheikh U. A fatal case of gram negative bacterial sepsis associated with disseminated strongyloidiasis in an immunocompromised patient. J Pak Med Assoc 2008;58:91–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Paola, Dias LB, da Silva J. Enteritis due to Strongyloides stercoralis. A report of 5 fatal cases. Am J Dig Dis 1962;7:1086–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genta RM, Caymmi-Gomes M. Pathology. In: Grove DI, ed Strongyloidiasis: a major roundworm infection of man. London: Taylor & Francis, 1989:105 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coutinho HB, Robalinho TI, Coutinho VB, et al. Immunocytochemistry of mucosal changes in patients infected with the intestinal nematode Strongyloides stercoralis. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:717–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suputtamongkol Y, Premasathian N, Bhumimuang K, et al. Efficacy and safety of single and double doses of ivermectin versus 7-day high dose albendazole for chronic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5:e1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]