Abstract

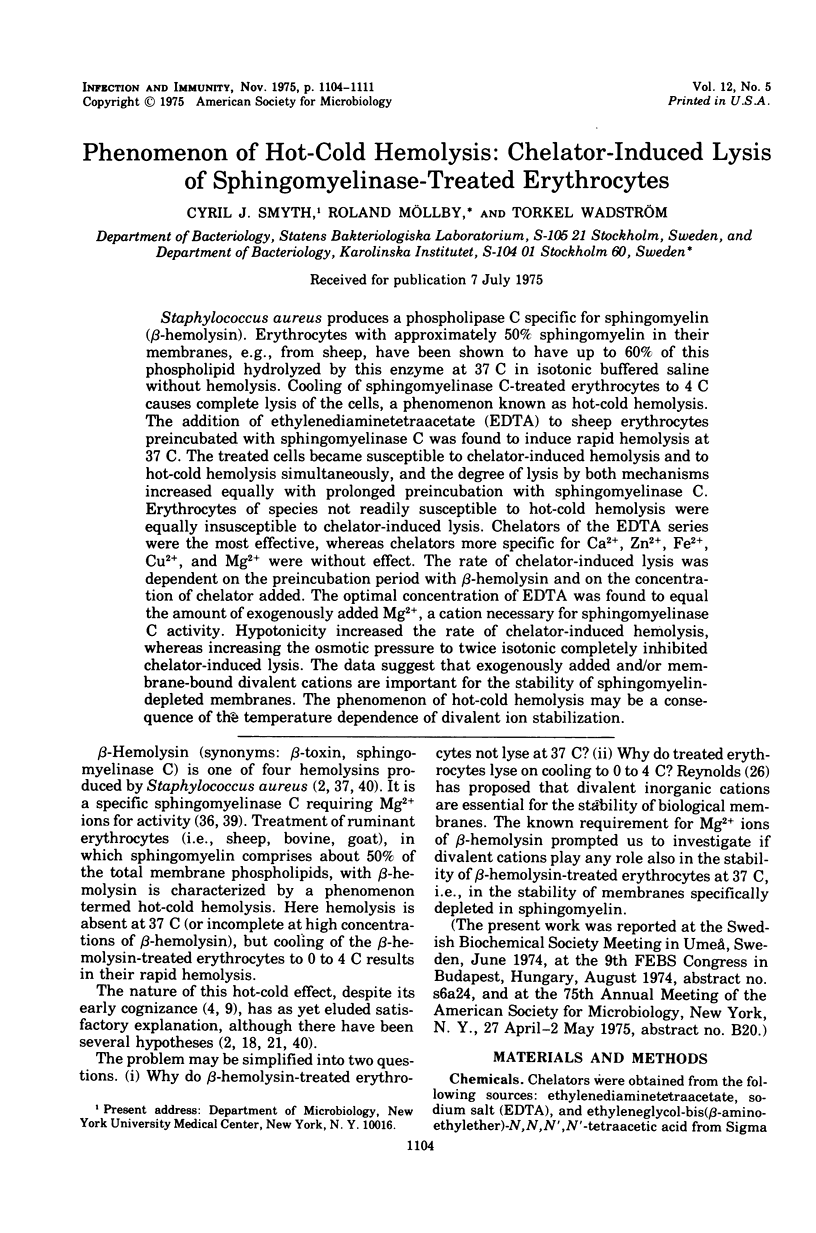

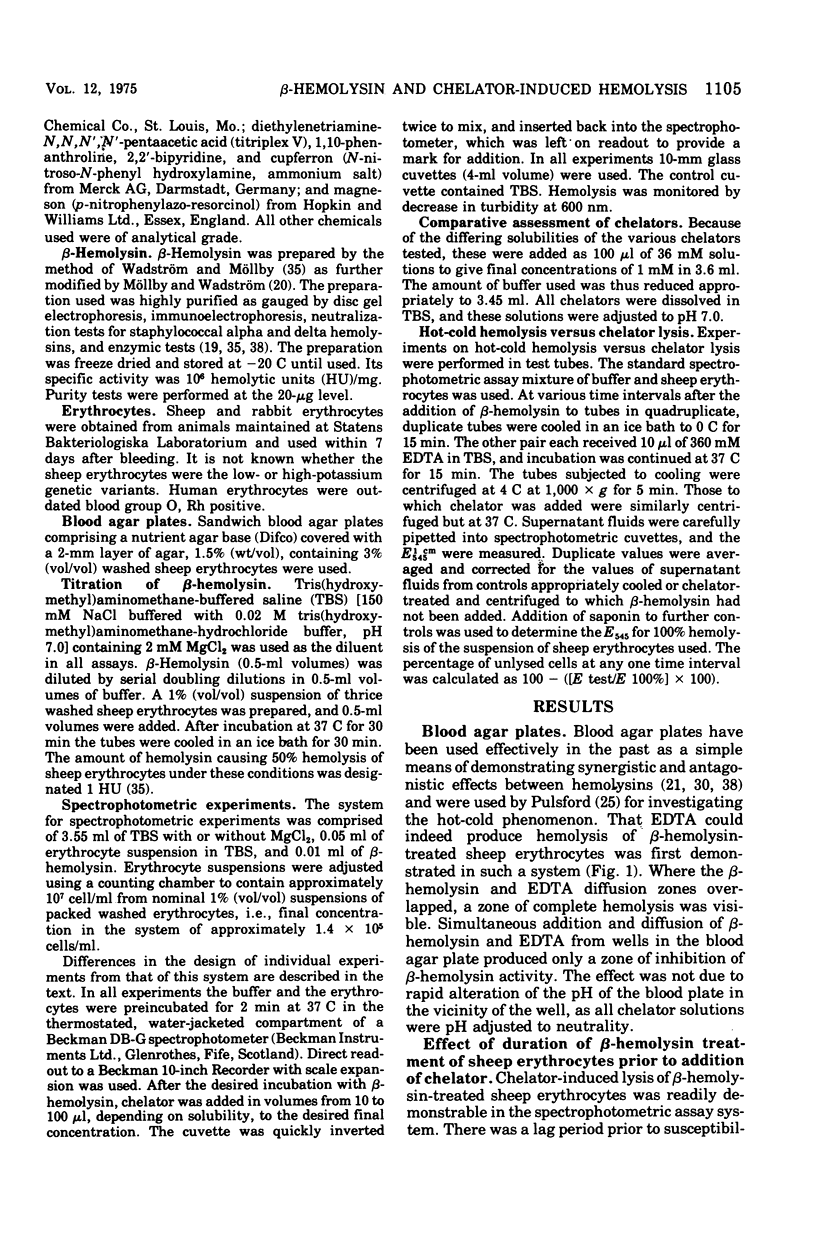

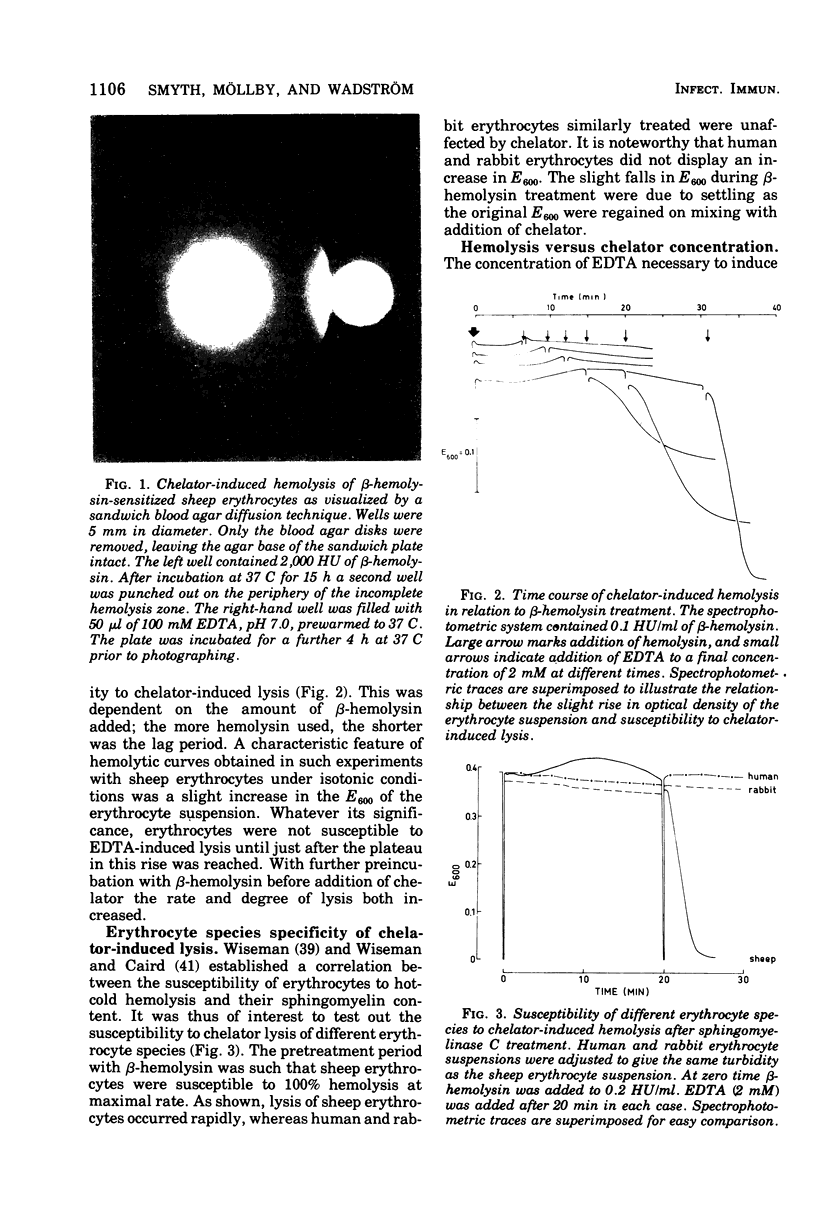

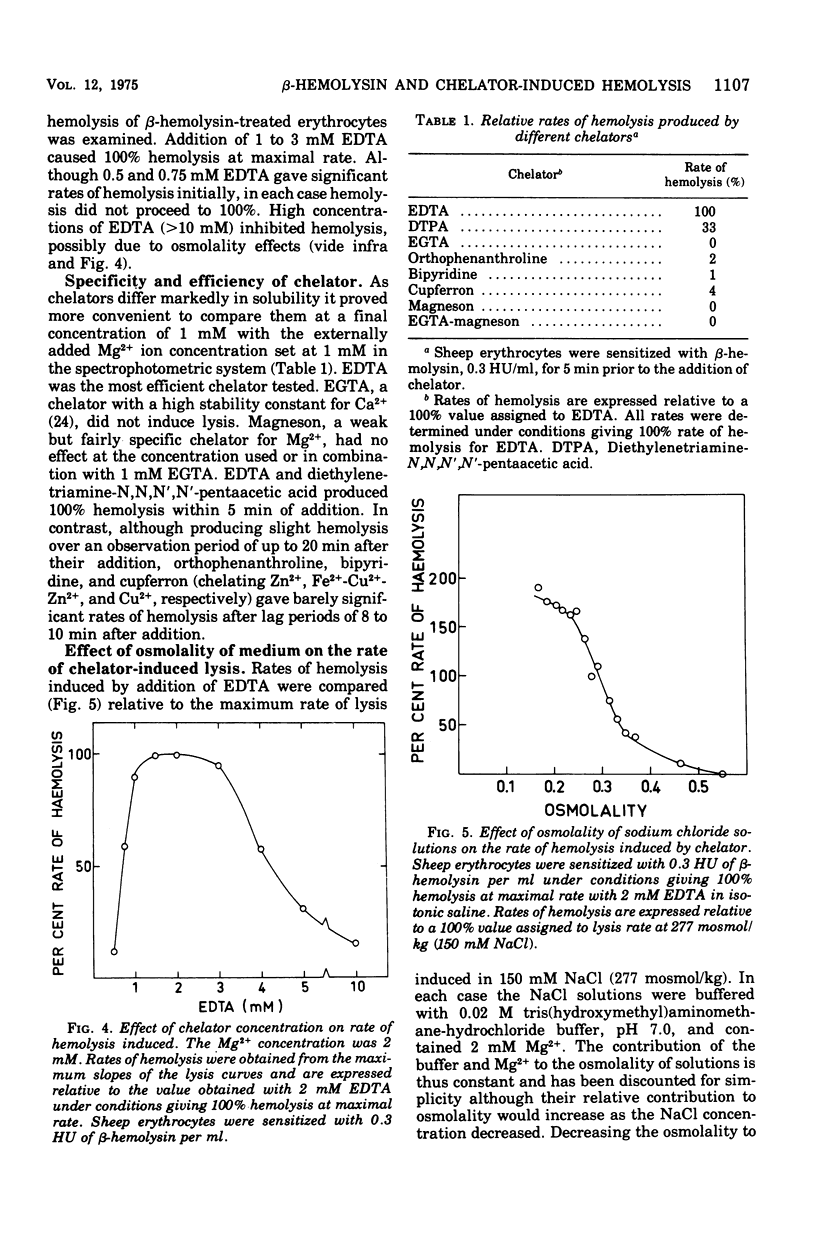

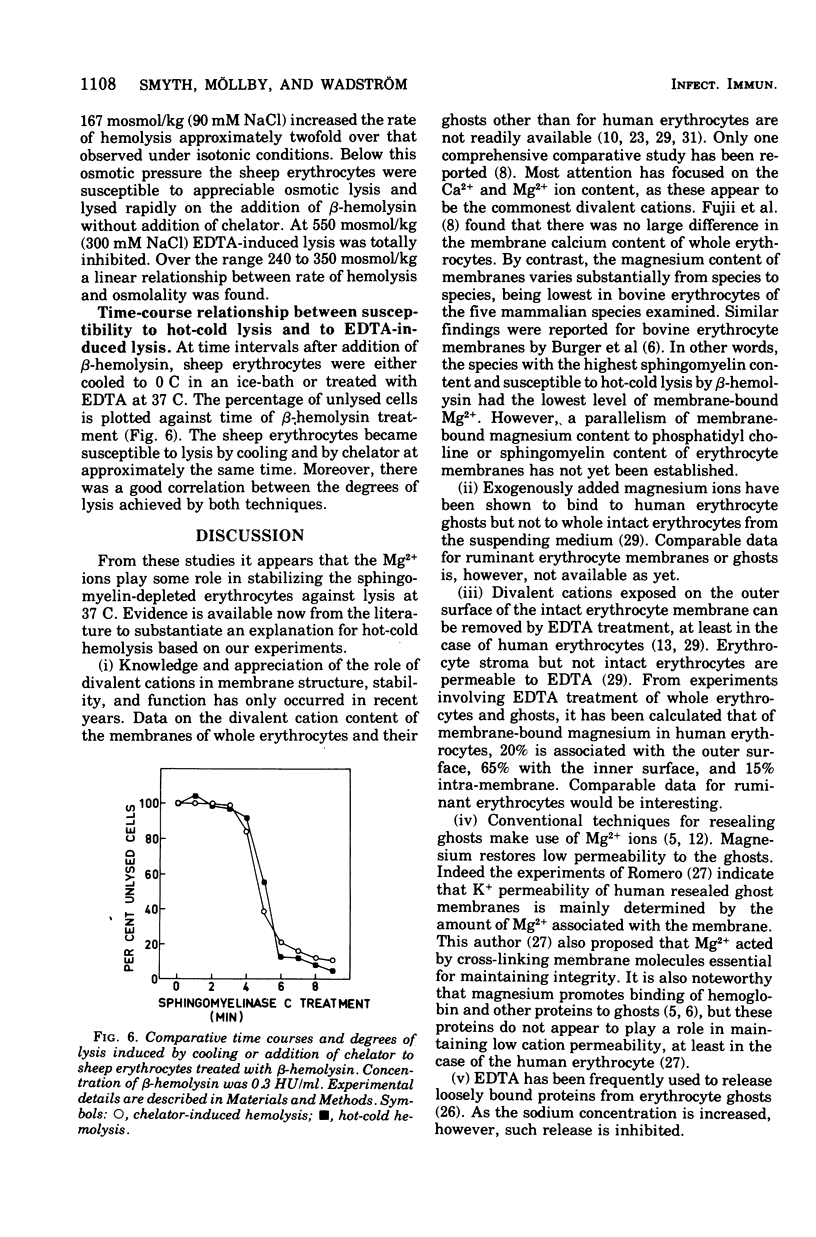

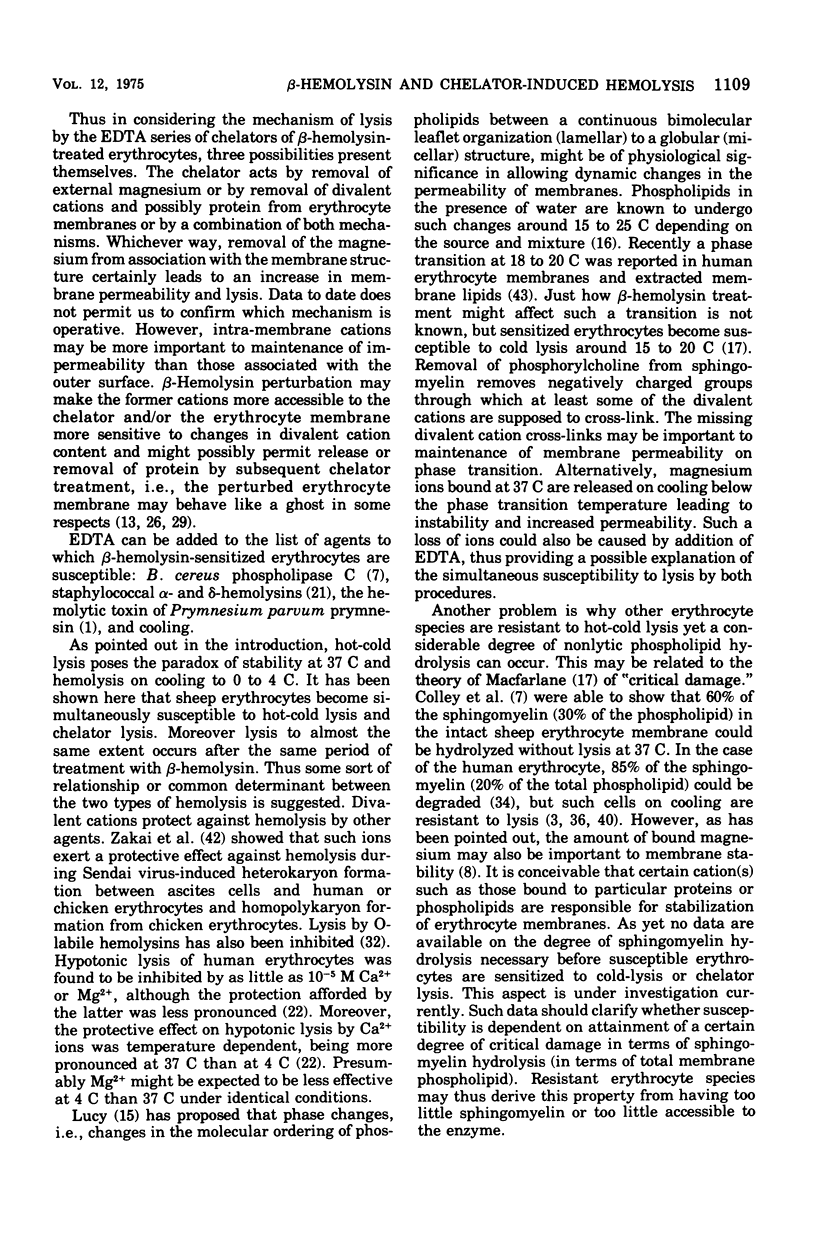

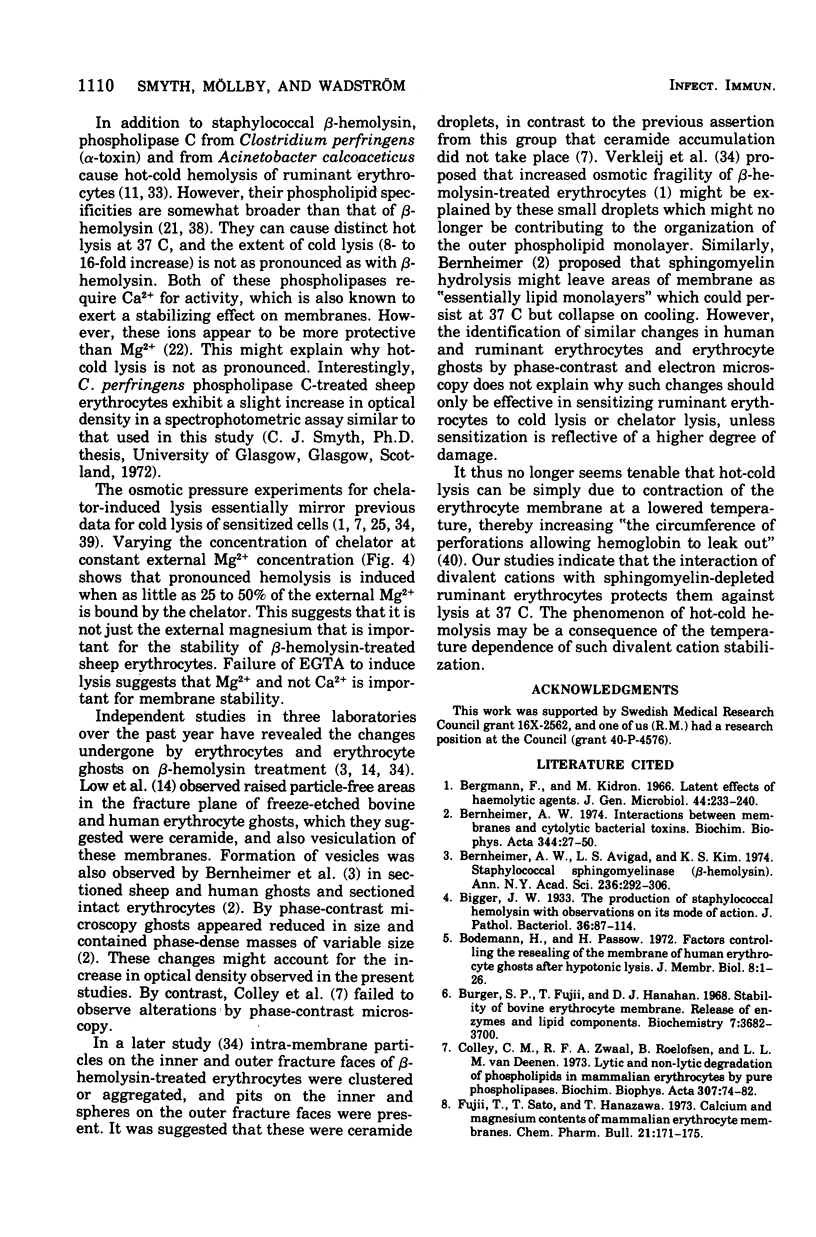

Staphylococcus aureus produces a phospholipase C specific for sphingomyelin (beta-hemolysin). Erythrocytes with approximately 50% sphingomyelin in their membranes, e.g., from sheep, have been shown to have up to 60% of this phospholipid hydrolyzed by this enzyme at 37 C in isotonic buffered saline without hemolysis. Cooling of sphingomyelinase C-treated erythrocytes to 4 C causes complete lysis of the cells, a phenomenon known as hot-cold hemolysis. The addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) to sheep erythrocytes preincubated with sphingomyelinase C was found to induce rapid hemolysis at 37 C. The treated cells became susceptible to chelator-induced hemolysis and to hot-cold hemolysis simultaneously, and the degree of lysis of both mechanisms increased equally with prolonged preincubation with sphingomyelinase C. Erythrocytes of species not readily susceptible to hot-cold hemolysis were equally insusceptible to chelator-induced lysis. Chelators of the EDTA series were the most effective, whereas chelators more specific for Ca2+, Zn2+, Fe2+, Cu2+, and Mg2+ were without effect. The rate of chelator-induced lysis was dependent on the preincubation period with beta-hemolysin and on the concentration of chelator added. The optimal concentration of EDTA was found to equal the amount of exogenously added Mg2+, a cation necessary for sphingomyelinase C activity. Hypotonicity increased the rate of chelator-induced hemolysis, whereas increasing the osmotic pressure to twice isotonic completely inhibited chelator-induced lysis. The data suggest that exogenously added and/or membrane-bound divalent cations are important for the stability of sphingomyelin-depleted membranes. The phenomenon of hot-cold hemolysis may be a consequence of the temperature dependence of divalent ion stabilization.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergmann F., Kidron M. Latent effects of haemolytic agents. J Gen Microbiol. 1966 Aug;44(2):233–240. doi: 10.1099/00221287-44-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer A. W., Avigad L. S., Kim K. S. Staphylococcal sphingomyelinase (beta-hemolysin). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974 Jul 31;236(0):292–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb41499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemann H., Passow H. Factors controlling the resealing of the membrane of human erythrocyte ghosts after hypotonic hemolysis. J Membr Biol. 1972;8(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01868092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger S. P., Fujii T., Hanahan D. J. Stability of the bovine erythrocyte membrane. Release of enzymes and lipid components. Biochemistry. 1968 Oct;7(10):3682–3700. doi: 10.1021/bi00850a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley C. M., Zwaal R. F., Roelofsen B., van Deenen L. L. Lytic and non-lytic degradation of phospholipids in mammalian erythrocytes by pure phospholipases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Apr 25;307(1):74–82. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T., Sato T., Hanzawa T. Calcium and magnesium contents of mammalian erythrocyte membranes. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1973 Jan;21(1):171–175. doi: 10.1248/cpb.21.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D. G., Long C. The calcium content of human erythrocytes. J Physiol. 1968 Dec;199(2):367–381. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUCY J. A. GLOBULAR LIPID MICELLES AND CELL MEMBRANES. J Theor Biol. 1964 Sep;7:360–373. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepke S., Passow H. The effect of pH at hemolysis on the reconstitution of low cation permeability in human erythrocyte ghosts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972 Feb 11;255(2):696–702. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(72)90174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman M. A., Weed R. I. Divalent cation content of normal and ATP-depleted erythrocytes and erythrocyte membranes. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1972 Nov-Dec;12(6):799–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low D. K., Freer J. H., Arbuthnott J. P., Möllby R., Wadström T. Consequences of spingomyelin degradation in erythrocyte ghost membranes by staphylococcal beta-toxin (sphingomyelinase C). Toxicon. 1974 May;12(3):279–285. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(74)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACFARLANE M. G. The biochemistry of bacterial toxins; variation in haemolytic activity of immunologically distinct lecithinases towards erythrocytes from different species. Biochem J. 1950 Sep;47(3):270–279. doi: 10.1042/bj0470270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meduski J. W., Hochstein P. Hot-cold hemolysis: the role of positively charged membrane phospholipids. Experientia. 1972 May 15;28(5):565–566. doi: 10.1007/BF01931879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murofushi M., Sato T., Fujii T. Protective effect of calcium ions on hypotonic hemolysis of human erythrocytes. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1973 Jun;21(6):1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllby R., Nord C. E., Wadström T. Biological activities contaminating preparations of phospholipase C ( -toxin) from Clostridium perfringens. Toxicon. 1973 Feb;11(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(73)90075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllby R., Wadström T. Purification of staphylococcal beta-, gamma- and delta-hemolysins. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1973;1:298–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllby R., Wadström T., Smyth C. J., Thelestam M. The interaction of phospholipase C from Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium perfringens with cell membranes. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1974;18(3):259–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olehy D. A., Schmitt R. A., Bethard W. F. Neutron activation analysis of magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium, manganese, cobalt, copper, zinc, sodium, and potassium in human erythrocytes and plasma. J Nucl Med. 1966 Dec;7(12):917–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PULSFORD M. F. Factors affecting the lysis of erythrocytes treated with staphylococcal beta toxin. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1954 Jun;32(3):347–352. doi: 10.1038/icb.1954.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J. A. Are inorganic cations esential for the stability of biological membranes? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1972 Jun 20;195:75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero P. J. The role of membrane-bound magnesium in the permeability of ghosts to K+. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974 Feb 26;339(1):116–125. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Fujii T. Binding of calcium and magnesium ions to human erythrocyte membranes. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1974 Feb;22(2):368–374. doi: 10.1248/cpb.22.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucková A., Soucek A. Inhibition of the hemolytic action of and lysins of Staphylococcus pyogenes by Corynebacterium hemolyticum, C. ovis and C. ulcerans. Toxicon. 1972 Aug;10(5):501–509. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(72)90176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALBERG L. S., HOLT J. M., PAULSON E., SZIVEK J. SPECTROCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF SODIUM, POTASSIUM, CALCIUM, MAGNESIUM, COPPER, AND ZINC IN NORMAL HUMAN ERYTHROCYTES. J Clin Invest. 1965 Mar;44:379–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI105151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Epps D. E., Andersen B. R. Streptolysin O II. Relationship of Sulfyhdryl Groups to Activity. Infect Immun. 1971 May;3(5):648–652. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.5.648-652.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heyningen W. E. The biochemistry of the gas gangrene toxins: Partial purification of the toxins of Cl. welchii, type A. Separation of alpha and theta toxins. Biochem J. 1941 Nov;35(10-11):1257–1269. doi: 10.1042/bj0351257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkleij A. J., Zwaal R. F., Roelofsen B., Comfurius P., Kastelijn D., van Deenen L. L. The asymmetric distribution of phospholipids in the human red cell membrane. A combined study using phospholipases and freeze-etch electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Oct 11;323(2):178–193. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISEMAN G. M. FACTORS AFFECTING THE SENSITIZATION OF SHEEP ERYTHROCYTES TO STAPHYLOCOCCAL BETA LYSIN. Can J Microbiol. 1965 Jun;11:463–471. doi: 10.1139/m65-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadström T., Möllby R. Studies on extracellular proteins from Staphylococcus aureus. VII. Studies on -haemolysin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971 Jul 21;242(1):308–320. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman G. M., Caird J. D. The nature of staphylococcal beta hemolysin. I. Mode of action. Can J Microbiol. 1967 Apr;13(4):369–376. doi: 10.1139/m67-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakai N., Loyter A., Kulka R. G. Prevention of hemolysis by bivalent metal ions during virus-induced fusion of erythrocytes with Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. FEBS Lett. 1974 Apr 1;40(2):331–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]