Abstract

The importance of the immune system in hypertension, vascular disease, and renal disease has been appreciated for over 50 years. Recent experimental advances have led to a greater appreciation of the mechanisms whereby inflammation and immunity participate in cardiovascular disease. In addition to the experimental data, multiple studies in patients have demonstrated a strong correlation between the observations made in animals and humans. Of great interest is the development of salt-sensitive hypertension in humans with the concurrent increase in albumin excretion rate. Experiments in our laboratory have demonstrated that feeding a high-NaCl diet to Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats results in a significant infiltration of T lymphocytes into the kidney that is accompanied by the development of hypertension and renal disease. The development of disease in the Dahl SS closely resembles observations made in patients; studies were therefore performed to investigate the pathological role of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in hypertension and renal disease. Pharmacological and genetic studies indicate that immune cell infiltration into the kidney amplifies the disease process. Further experiments demonstrated that infiltrating T cells may accentuate the Dahl SS phenotype by increasing intrarenal ANG II and oxidative stress. From these and other data, we hypothesize that infiltrating immune cells, which surround the blood vessels and tubules, can serve as a local source of bioactive molecules which mediate vascular constriction, increase tubular sodium reabsorption, and mediate the retention of sodium and water to amplify sodium-sensitive hypertension. Multiple experiments remain to be performed to refine and clarify this hypothesis.

Keywords: hypertension, infiltrating immune cells

cardiovascular diseases (e.g., stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, etc.) were listed as the underlying cause of death in 1 of every 3 deaths in the US in 2007–10 (24). Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease; greater than 30% of adults over the age of 20 have elevated arterial blood pressure (24). Hypertension is also one of the primary risk factors for chronic kidney disease (CKD); ∼26 million people in the US have CKD and 20 million are at increased risk for CKD (1). The cause of hypertension is generally unknown, although experimental and human data indicate that infiltration of immune cells into the kidney is important in the development of hypertension and kidney damage (29, 33, 34, 59, 69, 76). The role of immunity in hypertension and renal disease is only beginning to be understood and is the subject of this brief review.

As recently reviewed (27, 45, 64a, 71, 72), the importance of the immune system in hypertension, vascular disease, and renal disease has been appreciated by investigators for over 50 years. In that time period, a number of investigative groups have set out to explore different aspects of this interesting relationship. As described below, many provocative observations were made by different laboratories, but investigators were ultimately stymied by the lack of tools and reagents necessary to fully examine the role of the immune system in hypertension and renal disease and the sometimes conflicting nature of different observations. It has only been in the past decade, with the availability and use of modern immunological and genetic tools, that further progress has been made to begin to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms linking inflammation and immunity to cardiovascular and renal disease. The present review will focus upon recent experimental observations and correlate the observations made in animals to those observed in patients to lend a further understanding to human disease.

Role of the Immune System in Experimental Hypertension and Kidney Disease

Some of the earliest studies experimentally linking the immune systems with hypertension were performed by Grollman and colleagues (83) in the early to mid-1960's. Their work demonstrated that autoimmune factors play a role in renal infarction hypertension in rodents (83). They further demonstrated that hypertension can be transferred to normotensive rats by transplantation of lymph node cells from rats with renal infarct hypertension (55). Further studies in the mid-1970's demonstrated that an intact thymus is required for the maintenance of hypertension in mouse models of hypertension (78) and transfer of splenic cells from hypertensive rats led to elevations in blood pressure in normotensive recipients (58). Subsequently, pharmacological studies demonstrated that chronic immunosuppression attenuates hypertension in Okamoto spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) and in renal infarcted Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (36, 54). The important original studies by these investigative groups and others (37, 38) demonstrated the prohypertensive influence of the immune system in hypertension. In contrast, other experiments demonstrated that hypertension could be corrected by thymic transplant (2) or by administration of interleukin 2 (79) in SHR rats, indicating a potential hypotensive effect of the immune system. The work of these and other groups laid the groundwork for studies currently in progress, but their experimental efforts were largely stymied by the somewhat contradictory findings in different studies and the lack of specific reagents, assays, and methodologies necessary to fully address the interaction between immunity, hypertension, and renal damage.

In the past decade, a collaborative group of scientists from different institutions in North and South America has performed a number of studies illustrating the importance of infiltration and/or activation of immune cells in the pathogenesis of hypertension and/or renal disease in rats (7, 33, 34, 65–69). Perhaps the most definitive studies illustrating the importance of immune cells in hypertension have come from the group of David Harrison who utilized adoptive transfer of immune cells in immunodeficient mutant mice to demonstrate the importance of T lymphocytes in the development of ANG II hypertension (26, 27). Experimental reports from these groups, as well as further studies that demonstrated the importance of immune cells in lupus-related hypertension (48), intrauterine growth restriction hypertension (81), CNS-mediated hypertension (87), and ANG II-hypertension (11, 12), have confirmed and extended our understanding of the important role of immunity in hypertension. Together, these studies have spurred a great deal of interest in this field.

Role of the Immune System in Human Hypertension and Kidney Disease

Although there is a fairly extensive literature on this topic in animal models of disease, the literature in humans is not as sizeable. Nonetheless, data from patients are consistent with the observations made in animal studies that indicate that the immune system is important in the development of hypertension and kidney disease. Early observations demonstrated that lymphocytes infiltrate the renal interstitial spaces surrounding damaged glomeruli and tubules in hypertensive patients (74). Moreover, a strong correlation was observed between the degree of renal arteriolar sclerosis and the aggregation of lymphocytes observed in kidney biopsies (74). These observations were subsequently confirmed as it was demonstrated that an inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration occurs into the arterioles and small arteries obtained from the kidney or periadrenal tissue of patients with hypertension regardless of the origin of the disease (57). Additional studies demonstrated that the vascular necrosis and renal glomerular lesions in hypertensive patients with malignant nephrosclerosis are associated with deposition of gamma globulin and complement in the glomeruli and renal vessels (60). Lending further support for the role of immunity in human hypertension, elevated levels of serum immunoglobulins were observed in patients with hypertension when compared with normal patients (16, 56).

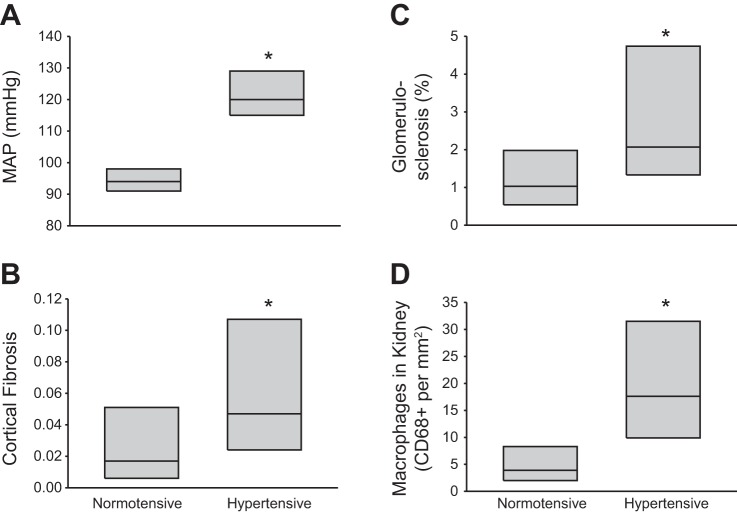

More recently, it has been shown that African-American and White hypertensives have glomerulosclerosis, renal fibrosis, and increased macrophages in the renal interstitium compared with normotensive patients (29). Data from this study are replotted in Fig. 1 and demonstrate that hypertensive African-American subjects have increased renal fibrosis, increased glomerulosclerosis, and increased macrophage infiltration in the kidney compared with normotensive individuals. Immunohistochemical evidence from that study indicated an infiltrate of macrophages and CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in fibrotic regions of the kidneys or areas with changes in glomerular morphology related to ischemia. Supporting the human findings, it was recently reported that the circulating levels of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 chemokines, which are homing chemokines for T cells, are increased in hypertensive patients (85). Moreover, patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis were demonstrated to have increased CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the tubulointerstitial space (85).

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP; A), renal cortical fibrosis (B), glomerulosclerosis (C), and infiltrating macrophages in the kidneys (D) of normotensive (n = 34) and hypertensive (n = 46) African-Americans. *P < 0.05 vs. normotensive group. Data are presented as the median with the 25th and 75th percentile. Redrawn with permission from Hughson et al. (29).

The correlation between infiltration of immune cells in the kidney and hypertension and/or renal disease in patients therefore appears quite clear. The functional role for these infiltrating cells in the elevation of blood pressure is not as well-defined, although several studies indicate that the severity of hypertension can be altered in patients receiving immunomodulatory therapy. The incidence of hypertension in AIDS patients is lower than in the non-HIV-positive patients; and interestingly, treatment of HIV-positive men with highly active retroviral therapy increased the incidence of hypertension to that of the general population (73). In another study, the administration of the immunosuppressive agent mycophenolate mofetil to a small number of patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis led to a reduction in mean arterial pressure that was reversible when the drug treatment was stopped (28). These findings lend support for a role of the immune system to promote the elevation of arterial pressure in hypertension. Although a cause and effect relationship cannot be determined in these studies, results of genetic association studies are also suggestive that the immune system is important in hypertension. Genetic markers in the regions of at least two genes involved in T lymphocyte signaling (SH2B3 and CD247) have been associated with hypertension in GWAS or other human genetic association studies (17, 20, 42). Together, the histological examination of immune cell infiltration, the functional effects of immunomodulatory therapy, and the genetic association studies provide good evidence that altered or inappropriate immune cell function may participate in hypertension and renal disease in patients.

Salt-Sensitive Hypertension

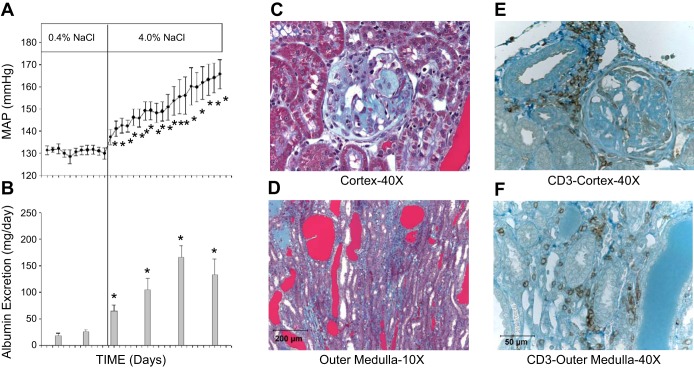

Work in our laboratory has examined the potential role of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney of Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats as the mediators of hypertension and renal damage. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the Dahl SS rat demonstrates a progressive increase in arterial blood pressure when the diet is switched from a low (0.4% NaCl)- to a high (4.0% NaCl)-salt content. This genetic model of hypertension exhibits many phenotypic characteristics in common with salt-sensitive hypertension in humans (8, 9, 18, 25, 40). As recently reviewed by Kotchen and colleagues (39), meta-analyses of human data indicate that hypertensive subjects demonstrate a sensitivity of blood pressure to sodium intake in excess of that observed in normotensive individuals. Depending on the criteria used to describe sodium sensitivity of blood pressure, between 30 and 50% of hypertensive humans exhibit a sensitivity of arterial pressure to sodium intake (35, 39), and it was further demonstrated that changes in mean arterial pressure in response to saline infusion or sodium and volume depletion are exaggerated in hypertensive humans compared with normotensive subjects (82). Moreover, the salt-sensitive response of blood pressure is greatly exaggerated in African-American hypertensive patients (82). Accompanying the increase in blood pressure in the Dahl SS rat is the development of albuminuria and renal histological damage (Fig. 2, B–D). This observation in the Dahl SS is also consistent with increased albuminuria observed in a group of Italian subjects with salt-sensitive hypertension (6). The Dahl SS rat therefore demonstrates many of the phenotypes observed in salt-sensitive hypertension in humans. The renal injury that occurs in Dahl SS rats following exposure to a diet containing elevated salt is also similar to that observed in the kidneys of rats with both experimental and genetic forms of hypertension and/or kidney disease (1, 63, 66, 67, 86). Of interest, the salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease observed in a number of other rodent models are associated with infiltration of immune cells into the kidney (47, 59, 68, 69) and are ameliorated by suppression of the immune system (1, 3, 63, 65, 67, 68). We subsequently performed studies to examine the importance of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney of the Dahl SS.

Fig. 2.

Development of hypertension (A) and albuminuria (B) in Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats when switched from a 0.4 to a 4.0% NaCl diet. Representative histological images of trichrome-stained sections of the renal cortex (C) and outer medulla (D) obtained from Dahl SS after 3 wk of 4.0% NaCl diet. Immunohistochemical images of CD3-positive T lymphocytes in the renal interstitial spaces in the renal cortex (E) and outer medulla (F) of Dahl SS rats fed the 4.0% NaCl diet for 3 wk. Data replotted with permission from De Miguel et al. (13).

Initial experiments were performed to examine immunoreactive markers of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney of Dahl SS rats (SS/JrHSDMcwi) fed high salt for 3 wk compared with age-matched rats maintained on a low-salt diet. Using immunoblotting protocols, we demonstrated that immunoreactive markers of macrophages, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes were all increased in the kidney of rats fed a high-salt diet (50). Further studies were then performed to isolate and assess the infiltrating immune cells using a combination of tissue digestion, density gradient centrifugation, antibody-labeled magnetic microbeads, and flow cytometry. A significant infiltration of macrophages and T lymphocytes was observed in the kidney of Dahl SS rats fed a high-salt diet (13, 50). A subsequent immunohistochemical localization of the infiltrating cells in the kidney indicated that the infiltrating macrophages (ED-1+ cells) are found surrounding damaged glomeruli and in the medullary interstitial spaces near blocked renal tubules (50). A further localization of T lymphocytes using CD3 or CD43 illustrated that the infiltrating T cells are also found surrounding damaged glomeruli and tubules in the renal medulla in addition to the regions surrounding renal blood vessels (Fig. 2, E-F) (13, 14). In contrast to the Dahl SS rat, the normal SD rat has much lower blood pressure, only traces of albumin are detected in the urine, and negligible renal damage is observed when fed a low-salt diet. These parameters are unchanged when a high-salt diet is administered for 3 wk, and SD rats demonstrate no infiltration of immune cells in the kidneys when the rats are fed high salt. The infiltration of immune cells into the kidney of Dahl SS rats is therefore likely related to the hypertensive disease phenotype.

Further flow cytometry and RNA expression studies were then performed to assess the infiltrating cells. Flow cytometry experiments demonstrated approximately equal number of T helper (CD4+) and cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) infiltrating the Dahl SS kidney (13). A subsequent gene expression analysis with real-time PCR on circulating T cells and T cells isolated from the kidneys revealed significantly greater expression (by 5- to 54-fold) of mRNA encoding inflammatory molecules associated with T cell signaling (70). These cytokines included proliferation factors such as IL-2 and factors associated with different T cell subtypes such as IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-6. The functional effects of infiltrating immune cells are presumably mediated via cytokines or other bioactive molecules released from these cells. Interestingly, IL-6 has been implicated as causative in angiotensin II (41) and cold-induced (10) hypertension. Other cytokines implicated in hypertension include tumor necrosis factor-α (80) and IL-17 (46). The role and mechanism of action of different cytokines in salt-sensitive hypertension are of primary interest and an avenue of active exploration. In the kidneys of Dahl SS rats, the increased expression of these factors along with other molecules associated with T cell activity demonstrates that the infiltrating T cells in the kidney have proliferated and are activated relative to circulating T lymphocytes.

These descriptive data demonstrate remarkable parallels between salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease in Dahl SS rats and humans. The Dahl SS exhibits an elevation of arterial pressure when sodium intake is increased; similarly, blood pressure is elevated in subjects from Japan, Italy, and the United States when NaCl intake is increased (6, 35, 82). The Dahl SS exhibits albuminuria and renal damage associated with the elevation of arterial pressure which occurs following a high-salt diet (13), similar to the increase albumin excretion in salt-sensitive humans (6) and consistent with the renal cortical fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis observed in hypertensive subjects (29). Finally, there is a significant infiltration of macrophages and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the kidneys of the Dahl SS fed high salt (6), an additional finding that is consistent with the human data (29). These experimental findings demonstrate that the Dahl SS rat may be a useful experimental model to explore the role of infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in salt-sensitive disease.

Functional Effects Of Immunomodulation In The Dahl SS Rat

To begin to elucidate the importance of the infiltrating immune cells in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease, we performed a number of experiments in which pharmacological inhibitors of the immune system were administered to Dahl SS rats during the period of high-NaCl intake (13–15, 50). The mechanistically different immunosuppressive agents mycophenolate mofetil, a purine synthesis inhibitor, and tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, were administered to groups of Dahl SS rats during the 3-wk period in which they were placed on the high-NaCl intake (13–15). The immunosuppressive treatments did not significantly alter circulating T cells but prevented the infiltration of T cells into the kidneys of the treated animals fed high salt (13–15). Correspondingly, the reduction in T cell infiltration was accompanied by a reduction of salt-sensitive hypertension, decreased albuminuria, and an attenuation of renal histological damage. Neither immunosuppressive agent reduced blood pressure when administered to control animals. Together, these pharmacological data indicate that immunosuppressive treatment attenuates the development of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage in the Dahl SS rat and is consistent with the observations made in humans. These data, however, do not definitively address the issue; the alteration of immune function in other organs or tissues could play a role in the hypertensive response, although it is most likely that the infiltrating cells in the kidney participate in the salt-induced kidney damage.

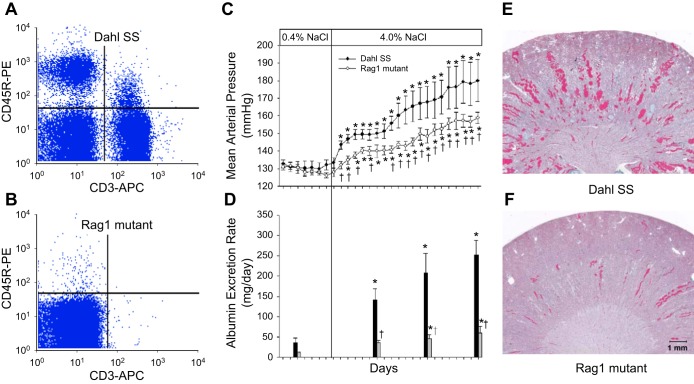

Experiments with immunosuppressive agents provided good evidence that the immune system is important on Dahl SS hypertension. To avoid the potential nonspecific side effects associated with immunosuppressive therapy and to begin to specifically target immune cell types in the Dahl SS rat, we utilized zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology, an approach recently described as an efficient means to generate targeted mutations in rats (22, 23), to delete recombination activating gene 1 (Rag1) in the Dahl SS genetic background. Null mutation of Rag1 in mice leads to the failure of T and B lymphocytes to mature (51). Targeting of exon 1 of Rag1 with the ZFN approach in the Dahl SS yielded a 13 base frame-shift mutation in the coding region of the Rag1 gene; this mutation led to a predicted stop codon downstream of the mutation. To document the null mutation of Rag1, Western blotting experiments confirmed the absence of immunoreactive Rag1 protein in the thymus of the mutant rats (49). Flow cytometry and immunohistochemical experiments then demonstrated that the Rag1 null mutant rats (SS-Rag1em1Mcwi) have a significant reduction in T and B lymphocytes in the circulation (Fig. 3, A–B) and spleen. No differences were noted in body weight between age-matched Rag1 mutant and wild-type rats. Further phenotyping experiments then demonstrated no difference in blood pressure or albumin excretion rate when the Dahl SS wild-type and Rag1 null mutant rats were fed the low-salt (0.4% NaCl) diet from weaning. Studies were then performed on SS and Rag1 null rats fed a diet containing 4.0% NaCl for 3 wk. The infiltration of T cells into the kidney following high salt was significantly blunted in the Rag1 null rats compared with the Dahl SS wild-type rats. Accompanying the reduction in infiltration of immune cells in the kidney, mean arterial blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion were significantly lower in Rag1 null mutants than in SS rats (Fig. 3, C–D). Finally, a histological analysis revealed that the glomerular and tubular damage in the kidneys of the SS rats fed high salt was also attenuated in the Rag1 mutants (Fig. 3, E–F). These studies demonstrate the importance of T cells or B cells in the pathogenesis of hypertension and renal damage in Dahl SS rats.

Fig. 3.

Representative flow cytometric demonstration of T-lymphocytes (CD-3) and B-lymphocytes (CD-45R) in the blood of Dahl SS (A) and Rag1 mutant rats (B). Development of hypertension (C) and albuminuria (D) in Dahl SS and Rag1 mutant rats when switched from a 0.4 to a 4.0% NaCl diet. Representative histological images of trichrome-stained kidneys (1× original magnification) obtained from Dahl SS (E) and Rag1 mutant rats (F) after 3 wk of 4.0% NaCl diet. Data replotted with permission from Mattson et al. (49).

The data from the Rag1 mutant rats indicated that T or B lymphocytes are important to amplify salt-sensitive hypertension in the Dahl SS. To more selectively address the question, we utilized the ZFN approach to selectively target T cells in the Dahl SS. The CD3 zeta chain, encoded by the CD247 gene, is involved in the assembly and expression of the T cell receptor complex as well as in signal transduction upon antigen triggering (30, 31, 77). Importantly, a patient with somatic mutations in the CD3 zeta chain was shown to have a reduction in circulating T cells with no change in B cells (64). Of additional interest, genetic variants in CD247 are associated with elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure in humans (17); manipulation of the CD3 zeta chain could therefore elucidate the role of T cells in Dahl SS hypertension and also demonstrate the functional effects of a gene that is associated with human hypertension.

To test the functional role of CD247 in hypertension and renal disease, the ZFN approach was utilized to induce an 11-bp frameshift deletion in exon 1 of CD247 (70). Western blotting confirmed the absence of CD247 protein in the thymus, and flow cytometry demonstrated that the CD247 mutant rats (SS-Cd247em1Mcwi) had a greater than 99% reduction in circulating CD3+ T cells compared with littermate controls. As observed for the Rag1 mutants, there was no difference in arterial pressure or albuminuria between the CD247 mutants and littermate wild-type controls when the rats were maintained on the 0.4% NaCl diet. After 3 wk of the 4.0% NaCl diet, the infiltration of CD3+ T cells into the kidney was significantly blunted in the CD247 mutant rats, although there was no significant difference in the number of infiltrating CD11b+ cells (macrophages/monocytes). Accompanying the reduced infiltration of T cells, mean arterial blood pressure was significantly lower in CD247 mutants than in littermate wild-type control rats after 3 wk of high salt. Moreover, urinary albumin and protein excretion rates and glomerular and renal tubular damage were also attenuated in the CD247 mutant animals. These studies demonstrate that functional T cells are required for the full development of Dahl SS hypertension and indicate that the association between CD247 and hypertension in humans may be related to altered immune cell function.

Mechanism of Action of Infiltrating T Cells

The experiments above which utilized immunosuppressive agents and genetic mutation of key genes in lymphocytes indicate that the T lymphocyte amplifies hypertension and renal damage in the Dahl SS rat (13–15, 49, 50, 70). This conclusion is consistent with work from a number of other groups demonstrating that the infiltration or activation of immune cells in the kidney may participate in the pathogenesis of hypertension and/or kidney disease (26, 27, 33, 34, 59, 69, 76). As we describe above, T cells and macrophages infiltrating the Dahl SS kidney are localized near damaged glomeruli and tubules and are also localized around blood vessels (13–15, 50). Interestingly, the infiltrating macrophages and T cells in the Dahl SS kidney are observed in the regions of marked tissue damage (13–15, 50, 52); similarly, macrophage and T cell infiltration in the kidneys of hypertensive patients has also been reported to occur in regions in which there is marked interstitial fibrosis and glomerul damage (29). These observations indicate that immune cells are participating in the histological and/or functional changes that occur in the kidney in hypertension. Consistent with the above observations, lymphocytes and macrophages have been localized in the renal interstitium of different rat models including hypertension induced by genetic or experimental elevation of ANG II (43, 53, 59), two-kidney one clip hypertension (47), l-NAME-induced hypertension (63), and genetically hypertensive rats (68). Immunohistochemical and immunoblotting studies have characterized the infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes (53, 59, 69, 76) as well as cells staining positive for superoxide (21, 68, 69) and angiotensin (21, 63, 67, 69) in the kidneys of hypertensive rats. Although the different cell types have been characterized, the mechanisms by which these immune cells lead to elevated levels of arterial blood pressure and renal end-organ damage are not clear. It has been proposed that the infiltration of immune cells leads to oxidative stress, and increased release of ANG II (21, 66, 69).

To address these possibilities, we performed experiments to examine the role of ANG II and free radicals in infiltrating T cells in the kidney. We observed that the increased renal infiltration of T lymphocytes, elevation of arterial blood pressure, and increased renal glomerular and tubular damage in Dahl SS rats fed high salt were associated with an inappropriate elevation of intrarenal ANG II (13). An analysis of circulating and intrarenal ANG II revealed that circulating ANG II was significantly decreased when Dahl SS rats were switched from a diet containing 0.4% NaCl to 4.0% NaCl, but renal tissue ANG II was not suppressed in the kidneys of SS rats fed 4.0% NaCl (13). In contrast, both circulating and intrarenal ANG II levels were suppressed in normotensive SD rats switched from the same low- to high-NaCl diet. To investigate the potential role of the infiltrating immune cells in the inappropriately elevated ANG II in the kidney, the systemic administration of the immunosuppressive agent mycophenolate mofetil was used to prevent the infiltration of T lymphocytes into the kidney and to attenuate Dahl SS hypertension and renal disease (13). Interestingly, in contrast to vehicle-treated rats, intrarenal ANG II significantly decreased in Dahl SS administered mycophenolate mofetil when fed high salt. These studies demonstrated a correlation between the infiltration of immune cells and the elevation of intrarenal ANG II. To establish a functional link between these observations, biochemical studies demonstrated that T lymphocytes isolated from the kidney possess renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme activity. These data indicate that infiltrating T cells are capable of participating in the production of ANG II and are associated with increased intrarenal ANG II, hypertension, and renal disease. As such, infiltrating cells may participate in the established phase of Dahl SS hypertension in part by increasing intrarenal ANG II.

A separate set of studies then demonstrated that the increase in infiltrating T cells in the kidney of Dahl SS rats fed high salt is also accompanied by an increase in urinary and renal tissue thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS; an index of oxidative stress) and an increase in immunoreactive subunits of NADPH oxidase in renal tissue (14). Rats treated with the immunosuppressive agent tacrolimus, which blocked the infiltration of T cells into the kidney, did not have an increase in NADPH oxidase expression in the kidney or elevated urine TBARS excretion compared with vehicle-treated Dahl SS fed high salt (14). Furthermore, an examination of the T cells infiltrating the kidney demonstrated that immunoreactive p67phox, gp91phox, and p47phox subunits of NADPH oxidase are enriched in the infiltrating cells (14). Blockade of renal infiltration of immune cells is therefore associated with decreased oxidative stress, an attenuation of hypertension, and a reduction of renal damage in Dahl SS rats fed high salt. These pharmacological experiments thus also support a role for the infiltrating T cells as a source of free radicals in the kidney. Consistent with a role of oxidative stress in the development of this salt-sensitive phenotype, genetic deletion of the NADPH oxidase subunit p67phox blunted salt-sensitive hypertension in the Dahl SS (19). These observations are consistent with the demonstrated importance of intact NADPH oxidase in T cells as an important mediator of ANG II-induced hypertension in mice (26). Since the mouse strain utilized in the ANG II-hypertension model is resistant to kidney damage, it is difficult to assess the potential role of NADPH oxidase in T cells as mediators of renal damage in the mouse model, although the data in the Dahl SS indicate an important role for free radicals produced by infiltrating T cells to mediate renal damage.

Mechanisms of Activation of the Infiltrating Cells

Although a large amount of data supports a role for inflammation in the kidney, the mechanisms leading to infiltration and activation of immune cells in the kidney have proven elusive. The cause of the accumulation of deleterious T lymphocytes in the kidney may be due to nonspecific chemokines or the result of a specific antigen-induced cellular immune response. Considering the central role played by T lymphocytes in the response, a classical cellular immune response would appear to be likely, although the identification of specific antigens or neoantigens has proven elusive.

As described above, the presence of lymphocytes in the renal interstitial space has been recognized for over 50 years, but lesser attention has been given to the potential antigen-presenting cells. Although antigen-presenting dendritic cells have been extensively examined in lymphoid tissue, until the past several years, relatively little attention was given to dendritic cells present in the kidney (32). Recent data indicate that dendritic cells form a continuous surveillance network throughout the renal interstitial space of mice (75) and humans (84) and are therefore poised to recognize foreign molecules throughout the renal parenchyma. The stimuli resulting in the presence of antigens or neoantigens in the kidney are unclear. One intriguing observation in Dahl SS rats demonstrated that the infiltration of ED-1-positive cells (macrophages/monocytes) and the renal tissue damage that occur in salt-sensitive hypertension are dependent on increased renal perfusion pressure (52). The dependence of elevated perfusion pressure as a stimulus for T cell infiltration has not been examined, but these observations raise the possibility that alterations in the tissue related to elevated hydrostatic pressure (barotrauma, altered cytokines, increased free radicals, etc.) may play a role in the infiltration of immune cells into the renal parenchyma.

The identity of the antigens or neoantigens is unclear, although there are several intriguing possibilities. A recent study by Rodriguez-Iturbe and colleagues (62, 67a) indicated that heat shock proteins (HSP), specifically HSP70, may play a role as an antigen mediating the immune response in renal hypertension. A modification of HSP70 could provide a common antigen for the infiltration of immune cells observed in the renal parenchyma in many different experimental models of hypertension as well as in human hypertension. Another intriguing observation by Macconi and colleagues (44) indicated that sequential proteolytic cleavage of albumin by proximal tubule cells and subsequently by renal dendritic cells can generate antigenic peptides. The HSPs, albumin cleavage products, or the formation of other neoantigens could all serve as an antigenic stimulus and mediate the localized inflammatory response in the kidney which amplifies hypertension and renal disease.

Conclusion

Based on the studies described in this review, the block diagram depicted in Fig. 4 illustrates our working hypothesis to explain the role of infiltrating immune cells in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal damage. We propose that arterial blood pressure is increased in salt-sensitive individuals following an elevation of sodium intake due to a primary defect affecting renal sodium handling. We further propose that the initial increase in blood pressure damages the kidney resulting in the formation or presentation of antigens and neoantigens or the release of cytokines, free radicals, or other chemotactic molecules that mediate the infiltration and activation of immune cells into the kidney. The infiltrating cells, which surround the blood vessels and tubules, can then serve as a local source of bioactive molecules (free radicals, ANG II, cytokines, etc.) which lead to vascular constriction and increased tubular sodium reabsorption. The resulting retention of sodium and water then leads to an enhancement of the initial increase in blood pressure. It is therefore our hypothesis that the infiltrating T cells, or other immune cells, function as secondary amplifiers of salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury.

Fig. 4.

Block diagram depicting proposed mechanism whereby infiltrating immune cells amplify sodium-sensitive hypertension and renal damage.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK96859 and HL116264.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.L.M. conception and design of research; D.L.M. performed experiments; D.L.M. analyzed data; D.L.M. interpreted results of experiments; D.L.M. prepared figures; D.L.M. drafted manuscript; D.L.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.L.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez V, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Pons H, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Overload proteinuria is followed by salt-sensitive hypertension caused by renal infiltration of immune cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F1132–F1141, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ba D, Takeichi N, Kodama T, Kobayashi H. Restoration of T cell depression and suppression of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) by thymus grafts or thymus extracts. J Immunol 128: 1211–1216, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendich A, Belisle EH, Strausser. Immune system modulation and its effect on the blood pressure of the spontaneously hypertensive male and female rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 99: 600–607, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigazzi R, Bianchi S, Baldari D, Sgherri G, Baldari G, Campese VM. Microalbuminuria in salt-sensitive patients. A marker for renal and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension 23: 195–199, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bravo Y, Quiroz Y, Ferrebuz A, Vaziri ND, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil administration reduces renal inflammation, oxidative stress, and arterial pressure in rats with lead-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F616–F623, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campese VM. Salt sensitivity in hypertension. Hypertension 23: 531–550, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowley AW, Jr, Roman RJ. The role of the kidney in hypertension. JAMA 275: 1581–1589, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosswhite P, Sun Z. Ribonucleic acid interference knockdown of interleukin 6 attenuates cold-induced hypertension. Hypertension 55: 1484–1491, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowley SD, Song YS, Sprung G, Griffiths R, Sparks M, Yan M, Burchette JL, Howell DN, Lin EE, Okeiyi B, Stegbauer J, Yang Y, Tharaux PL, Ruiz P. A role for angiotensin II type 1 receptors on bone marrow-derived cells in the pathogenesis of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 55: 99–108, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowley SD, Frey CW, Gould SK, Griffiths R, Ruiz P, Burchette JL, Howell DN, Makhanova N, Yan M, Kim HS, Tharaux PL, Coffman TM. Stimulation of lymphocyte responses by angiotensin II promotes kidney injury in hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F515–F524, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Miguel C, Das S, Lund H, Mattson DL. T-lymphocytes mediate hypertension and kidney damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R1136–R1142, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Miguel C, Lund H, Di F, Mattson DL. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and lead to hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F734–F742, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Miguel C, Lund H, Mattson DL. High dietary protein exacerbates hypertension and renal damage in Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats by increasing infiltrating immune cells. Hypertension 57: 269–274, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebringer A, Doyle AE. Raised serum IgG levels in hypertension. Br Med J 5702: 146–148, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehret GB, O'Connor AA, Weder A, Cooper RS, Chakravarti A. Follow-up of a major linkage peak on chromosome 1 reveals suggestive QTLs associated with essential hypertension: GenNet study. Eur J Hum Genet 17: 1650–1657, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman HI, Klag MJ, Chiapella AP, Whelton PK. End-stage renal disease in US minority groups. Am J Kidney Dis 19: 397–410, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng D, Yang C, Geurts A, Kurth T, Liang M, Lazar J, Mattson D, O'Connor P, Cowley AW., Jr. Increased expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunit p67phox in the renal medulla contributes to excess oxidative stress and salt-sensitive hypertension. Cell Metab 15: 201–208, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox ER, Young JH, Li Y, Dreisbach AW, Keating BJ, Musani SK, Liu K, Morrison AC, Ganesh S, Kutlar A, Ramachandran VS, Polak JF, Fabsitz RR, Dries DL, Farlow DN, Redline S, Adeyemo A, Hirschorn JN, Sun YV, Wyatt SB, Penman AD, Palmas W, Rotter JI, Townsend RR, Doumatey AP, Tayo BO, Mosley TH, Jr, Lyon HN, Kang SJ, Rotimi CN, Cooper RS, Franceschini N, Curb JD, Martin LW, Eaton CB, Kardia SL, Taylor HA, Caulfield MJ, Ehret GB, Johnson T; International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-wide Association Studies (ICBP-GWAS) Chakravarti A, Zhu X, Levy D. Association of genetic variation with systolic and diastolic blood pressure among African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource study. Hum Mol Genet 20: 2273–2284, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franco M, Martinez F, Quiroz Y, Galicia O, Bautista R, Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Renal angiotensin II concentration and interstitial infiltration of immune cells are correlated with blood pressure levels in salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R251–R256, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Remy S, Cui X, Tesson L, Usal C, Menoret S, Jacob HJ, Anegon I, Buelow R. Generation of gene-specific mutated rats using zinc-finger nucleases. Methods Mol Biol 597: 211–225, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, Zeitler B, Miller JC, Choi VM, Jenkins SS, Wood A, Cui X, Meng X, Vincent A, Lam S, Michalkiewicz M, Schilling R, Foeckler J, Kalloway S, Weiler H, Ménoret S, Anegon I, Davis GD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jacob HJ, Buelow R. Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases. Science 325: 433, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129: e28–e292, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grim CE, Wilson TW, Nicholson GD, Hassell TA, Fraser HS, Grim CM, Wilson DM. Blood pressure in blacks. Hypertension 15: 803–809, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, hypertension. Hypertension 57: 132–140, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, García MacGregor E, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 218–225, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughson MD, Gobe GC, Hoy WE, Manning RD, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF. Associations of glomerular number and birth weight with clinicopathological features of African Americans and Whites. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 18–28, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irving BA, Chan AC, Weiss A. Functional characterization of a signal transducing motif present in the T cell antigen receptor zeta chain. J Exp Med 177: 1093–1103, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh Y, Matsuura A, Kinebuchi M, Honda R, Takayama S, Ichimiya S, Kon S, Kikuchi K. Structural analysis of the CD3 zeta/eta locus of the rat. Expression of zeta but not eta transcripts by rat T cells. J Immunol 151: 4705–4717, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John R, Nelson PJ. Dendritic cells in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2628–2635, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Nakagawa T, Kang DH, Feig DI, Herrera-Acosta J. Subtle renal injury is a likely common mechanism for salt-sensitive essential hypertension. Hypertension 45: 326–330, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson RJ, Herrera-Acosta J, Schreiner GF, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Subtle acquired renal injury as a mechanism of salt-sensitive hypertension. N Engl J Med 346: 913–923, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawasaki T, Delea CS, Bartter FC, Smith H. The effect of high-sodium and low-sodium intakes on blood pressure and other related variables in human subjects with idiopathic hypertension. Am J Med 64: 193–198, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khraibi AA, Norman RA, Dzielak DJ. Chronic immunosuppression attenuates hypertension in Okamoto spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 247: H722–H726, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khraibi AA, Smith TL, Hutchins PM, Lynch CD, Dusseau JW. Thymectomy delays the development of hypertension in Okamoto spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 5: 537–541, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khraibi AA. Association between disturbances in the immune system and hypertension. Am J Hypertens 4: 635–641, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotchen TA, Cowley AW, Jr, Frohlich ED. Salt in health and disease-a delicate balance. N Engl J Med 368: 1229–1237, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lackland DT, Keil JE. Epidemiology of hypertension in African Americans. Semin Nephrol 16: 63–70, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DL, Sturgis LC, Labazi H, Osborne JB, Jr, Fleming C, Pollock JS, Manhiani M, Imig JD, Brands MW. Angiotensin II hypertension is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H935–H940, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, Glazer NL, Morrison AC, Johnson AD, Aspelund T, Aulchenko Y, Lumley T, Köttgen A, Vasan RS, Rivadeneira F, Eiriksdottir G, Guo X, Arking DE, Mitchell GF, Mattace-Raso FU, Smith AV, Taylor K, Scharpf RB, Hwang SJ, Sijbrands EJ, Bis J, Harris TB, Ganesh SK, O'Donnell CJ, Hofman A, Rotter JI, Coresh J, Benjamin EJ, Uitterlinden AG, Heiss G, Fox CS, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Wang TJ, Gudnason V, Larson MG, Chakravarti A, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet 41: 677–687, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lombardi D, Gordon K, Polinksy P, Suga S, Scwartz S, Johnson R. Salt sensitive hypertension develops after short-term exposure to angiotensin II. Hypertension 33: 1013–1019, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macconi D, Chiabrando C, Schiarea S, Aiello S, Cassis L, Gagliardini E, Noris M, Buelli S, Zoja C, Corna D, Mele C, Fanelli R, Remuzzi G, Benigni A. Proteasomal processing of albumin by renal dendritic cells generates antigenic peptides. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 123–130, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Synapses, signals, cds, and cytokines interactions of the autonomic nervous system and immunity in hypertension. Circ Res 111: 1113–1116, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 500–507, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mai M, Geiger H, Hilgens KF, Veelken R, Mann JFE, Daemmrich J, Luft FC. Early changes in hypertension induced renal injury. Hypertension 22: 754–765, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathis KW, Venegas-Pont M, Masterson CW, Stewart NJ, Wasson KL, Ryan MJ. Oxidative stress promotes hypertension and albuminuria during the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension 59: 673–679, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattson DL, Lund H, Guo C, Rudemiller N, Geurts AM, Jacob H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R407–R414, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mattson DL, James L, Berdan EA, Meister CJ. Immune suppression attenuates hypertension and renal disease in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension 48: 149–156, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. Rag-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell 68: 869–877, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mori T, Polichnowski A, Glocka P, Kaldunski M, Ohsaki Y, Liang M, Cowley AW., Jr High perfusion pressure accelerates renal injury in salt-sensitive hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1472–1482, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller DN, Shagdarsuren E, Park JK, Dechend R, Mervaala E, Hampich F, Fiebeler A, Ju X, Finckenberg P, Theuer J, Viedt C, Kreuzer J, Heidecke H, Haller H, Zenke M, Luft FC. Immunosuppressive treatment protects against angiotensin II-induced renal damage. Am J Pathol 161: 1679–1693, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norman RA, Jr, Galloway PG, Dzielak DJ, Huang M. Mechanisms of partial infarct hypertension. J Hypertens 6: 397–403, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okuda T, Grollman A. Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Tex Rep Biol Med 25: 257–264, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olsen F. Immunological factors and high blood pressure in man. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Sect A Pathol 80: 257–259, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen F. Inflammatory cellular reaction in hypertensive vascular disease in man. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Sect A Pathol 80: 253–256, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olsen F. Transfer of arterial hypertension by splenic cells from DOCA-salt hypertensive and renal hypertensive rats to normotensive recipients. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand C 88: 1–5, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozawa Y, Kobori H, Suzaki Y, Navar LG. Sustained renal interstitial macrophage infiltration following chronic angiotensin II infusions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F330–F339, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paronetto F. Immunocytochemical observations on the vascular necrosis and renal glomerular lesions of malignant nephrosclerosis. Am J Pathol 46: 901–915, 1965 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pechman KR, Basile DP, Lund H, Mattson DL. Immune suppression blocks sodium-sensitive hypertension following recovery from ischemic acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1234–R1239, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pons H, Ferrebuz A, Quiroz Y, Romero-Vasquez F, Parra G, Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Immune reactivity to heat shock protein 70 expressed in the kidney is cause of salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F289–F299, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quiroz Y, Pons H, Gordon KL, Rincón J, Chávez M, Parra G, Herrera-Acosta J, Gómez-Garre D, Larfo R, Egido J, Johnson RJ, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F38–F47, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rieux-Laucat F, Hivroz C, Lim A, Mateo V, Pellier I, Selz F, Fischer A, Le Deist F. Inherited and somatic CD3ζ mutations in a patient with T-cell deficiency. N Engl J Med 354: 1913–1921, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64a.Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Renal infiltration of immunocompetent cells: cause and effect of sodium-sensitive hypertension. Clin Exp Nephrol 14: 105–111, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: all for one and one for all. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F606–F616, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Johnson RJ. The role of inflammatory cells in the kidney in the induction and maintenance of hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 260–263, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Gordon K, Rincón J, Chávez M, Parra G, Herrera-Acosta J, Gomez-Garre D, Largo R, Egido J, Johnson RJ. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin II exposure. Kidney Int 59: 2222–2232, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67a.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 56–62, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Bonet L, Chávez M, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ, Pons HA. Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F191–F201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: all for one and one for all. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F606–F616, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rudemiller N, Lund H, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Mattson DL. CD247 modulates blood pressure by altering T lymphocyte infiltration in the kidney. Hypertension 63: 559–564, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ryan MJ. An update on immune system activation in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Hypertension 62: 226–230, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schiffrin EL. T lymphocytes: a role in hypertension? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 181–186, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seaberg EC, Muñoz A, Lu M, Detels R, Margolick JB, Riddler SA, Williams CM, Phair JP. Multicenter Cohort Study AIDS. Association between highly active antiretroviral therapy and hypertension in a large cohort of men followed from 1984 to 2003. AIDS 19: 953–960, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sommers SC, Relman AS, Smithwick RH. Histologic studies of kidney biopsy specimens from patients with hypertension. Am J Pathol 34: 685–715, 1958 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soos TJ, Sims TN, Barisoni L, Lin K, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Nelson PJ. CX3CR1+ interstitial dendritic cells form a contiguous network throughout the entire kidney. Kidney Int 70: 591–596, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stewart T, Jung FF, Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Kidney immune cell infiltration and oxidative stress contribute to prenatally programmed hypertension. Kidney Int 68: 2180–2188, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sussman JJ, Bonifacino JS, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Weissman AM, Saito T, Klausner RD, Ashwell JD. Failure to synthesize the T Cell CD3-ζ chain: structure and function of a partial T cell receptor complex. Cell 52: 85–96, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Svendsen UG. Evidence for an initial, thymus independent and a chronic, thymus dependent phase of DOCA and salt hypertension in mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 84: 523–528, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuttle RS, Boppana DP. Antihypertensive effect of interleukin-2. Hypertension 15: 89–94, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Venegas-Pont M, Manigrasso MB, Grifoni SC, Lamarca BB, Maric C, Racusen LC, Glover PH, Jones AV, Drummond HA, Ryan MJ. Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist etanercept decreases blood pressure and protects the kidney in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Hypertension 56: 643–649, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillon P, Weimer A, Edholm E, Bengten E, Wilson M, Martin JN, Jr, LaMarca B. CD4+ T helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 57: 949–955, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weinberger MH, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Grim CE, Fineberg NS. Definitions and characteristics of sodium sensitivity and blood pressure resistance. Hypertension 8: II127–II134, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.White FN, Grollman A. Autoimmune factors associated with infarction of the kidney. Nephron 1: 93–102, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Woltman AM, de Fijter JW, Zuidwijk K, Vlug AG, Bajema IM, van der Kooij SW, van Ham V, van Kooten C. Quantification of dendritic cell subsets in human renal tissue under normal and pathological conditions. Kidney Int 71: 1001–1008, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Youn JC, Yu HT, Lim BJ, Koh MJ, Lee J, Chang DY, Choi YS, Lee SH, Kang SM, Jang Y, Yoo OJ, Shin EC, Park S. Immunosenescent CD8+ T cells and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 chemokines are increased in human hypertension. Hypertension 62: 126–133, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zatz R, Noronha IL, Fujihara CK. Experimental and clinical rationale for use of MMF in nontransplant progressive nephropathies. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F1167–F1175, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zubcevic J, Waki H, Raizada MK, Paton JF. Autonomic-immune-vascular interaction: an emerging concept for neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension 57: 1026–1033, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]