Abstract

The actions of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the kidney are mediated by G protein-coupled E-prostanoid (EP) receptors, which affect renal growth and function. This report examines the role of EP receptors in mediating the effects of PGE2 on Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell growth. The results indicate that activation of Gs-coupled EP2 and EP4 by PGE2 results in increased growth, while EP1 activation is growth inhibitory. Indeed, two EP1 antagonists (ONO-8711 and SC51089) stimulate, rather than inhibit, MDCK cell growth, an effect that is lost following an EP1 knockdown. Similar observations were made with M1 collecting duct and rabbit kidney proximal tubule cells. ONO-8711 even stimulates growth in the absence of exogenous PGE2, an effect that is prevented by ibuprofen (indicating a dependence upon endogenous PGE2). The involvement of Akt was indicated by the observation that 1) ONO-8711 and SC51089 increase Akt phosphorylation, and 2) MK2206, an Akt inhibitor, prevents the increased growth caused by ONO-8711. The involvement of the EGF receptor (EGFR) was indicated by 1) the increased phosphorylation of the EGFR caused by SC51089 and 2) the loss of the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 and SC51089 caused by the EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478. The growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 was lost following an EGFR knockdown, and transduction of MDCK cells with a dominant negative EGFR. These results support the hypothesis that 1) signaling via the EP1 receptor involves Akt as well as the EGFR, and 2), EP1 receptor pharmacology may be employed to prevent the aberrant growth associated with a number of renal diseases.

Keywords: prostaglandin E2, kidney epithelial cell growth, EP receptors

prostaglandin e2 (pge2), the predominant product of arachidonic acid in the kidney, controls renal function by a number of different means (5). PGE2 regulates salt and water reabsorption by tubular epithelial cells, glomerular filtration (41), renal blood flow (34), and the renin-angiotensin system (11). In addition, PGE2 has been implicated as playing a role in the progression of a number of renal diseases, including diabetic nephropathy (36), glomerulonephritis (44), and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (33).

The effects of PGE2 are mediated by its interaction with four different subtypes of G protein-coupled EP receptors (8), including Gs-coupled EP2 and EP4, which activate adenylate cyclase (AC), Gi-coupled EP3, coupled to Gi, which reduces AC activity as well as Gq-coupled EP1, which activates PLC, resulting in an increase in intracellular Ca2+, and the activation of PKC. All four subtypes of EP receptors are present in the kidney (9). Especially high levels of EP1, EP3, and EP4 are present in the collecting duct, where these receptors regulate salt and water reabsorption. While EP receptor levels are not necessarily as high elsewhere in the kidney, EP receptors nevertheless control a number of reabsorptive processes in other nephron segments, as exemplified by its regulation of Na+-phosphate cotransporters in the renal proximal tubule (RPT) (49) and Na-K-ATPase in the distal tubule (58).

EP2 and/or EP4 receptors reportedly are protective in a number of renal disease states, unlike EP1. Indeed, activation of EP4 (using the EP4 agonist CP-044, 519-02) reduced RPT necrosis and apoptosis in a mercuric chloride model of acute renal failure (57). Similarly, EP2 and EP4 receptor activation increased growth (and reduced apoptosis) in renal proximal and distal tubules in a rat model of chronic renal failure (57). In contrast, antagonism of EP1 (rather than activation of EP1 by agonists) has been reported to be protective. For example, EP1 antagonism (by the EP1-selective antagonist ONO-8713) prevented progressive renal damage in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRSP) (48). Similarly, the development of nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats was retarded by EP1 antagonists (6, 35, 36). It is unclear whether 1) EP1 receptors have direct, or indirect roles in these processes, and 2) whether kidney epithelial cell growth is affected in these disease states, as a consequence of EP1 receptor activation.

Previously, we observed stimulatory effects of PGE2 on both the growth and transport of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells in hormonally defined serum-free medium (50, 55). However, the growth-stimulatory effects of PGE1 and PGE2 were no longer observed in PGE1-independent MDCK cells with elevated intracellular cAMP levels (53). These latter observations can be explained by the involvement of EP2 and/or EP4 receptors in mediating the growth-stimulatory effects of PGE1 and PGE2. Similarly, the stimulatory effect of PGE2 on Na-K-ATPase was lost in dibutyryl cAMP-resistant MDCK cells defective in cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), also consistent with the involvement of EP2 and EP4 receptors (due to their ability to activate AC) (14). Subsequently, we found that the stimulatory effects of PGE2 on Na-K-ATPase could be attributed to transcriptional control of the Na-K-ATPase β-subunit gene and that EP1 and EP2 were involved, although all 4 EP receptors are present in MDCK cells (38, 39, 50). Similarly, our studies indicated that EP1, EP2, as well as EP4 were involved in transcriptional regulation of the Na-K-ATPase β-subunit gene in primary rabbit RPT cells (25).

This report evaluates whether Gq-coupled as well as Gs-coupled EP receptors similarly mediate the growth-stimulatory effects of PGE2 on MDCK cells. Our results indicate that both EP2 and EP4 are involved in mediating the growth-stimulatory effects of PGE2 in MDCK cells, while EP1 is growth inhibitory, placing a brake on EP2- and EP4-mediated control. Our results indicate that Akt as well as the EGF receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase are both included among the signaling pathways responsible for growth regulation mediated via EP1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Hormones, human transferrin, and other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). DMEM, Ham's F12 medium (F12), and soybean trypsin inhibitor were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The rabbit polyclonal antibodies against p-Akt 1/2/3 (sc-33437), the goat polyclonal antibodies against Akt1 (sc-1618) and EGFR (sc-03-G), and the mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (sc-47778) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against human EP1 (LS-A962–50) was from Lifespan Biosciences. The rabbit anti-goat horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate, the goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate, the Immun-Star HRP Substrate, nitrocellulose, acrylamide, and other electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). LucentBlue X-ray film was from Advansta (Menlo Park, CA). The Prism 6 program was obtained from GraphPad Software, (San Diego, CA). Lentiviral particles containing a pLKO.1 vector expressing short hairpin (sh) RNA against 1) the EP1 receptor (TRCN0000415217) with the sequence CCGGATCATGGTGGTGTCGTGCATCCTCGAGGATGCACGACACCACCATGATTTTTTTG, which is present in both the human and dog EP1 receptor; 2) the EGFR (TRCN0000295971) with the sequence CCGGCCTCCAGAGGATGTTCAATAACTCGAGTTATTGAACATCCTCTGGAGGTTTTTG, present in both human and dog EP1; and 3) the empty vector were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The dominant negative EGFR mutant HER CD533 (26) in pcDNA3 and the empty vector pcDNA3 were obtained from Sylvain Meloche (Montreal, Quebec). The M1 mouse collecting duct cell line was obtained from Alejandro Bertorello (Stockholm, Sweden).

Kidney cell cultures.

The basal medium (DME/F12) consisted of a 50:50 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 supplemented with 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 20 mM sodium bicarbonate, penicillin, and streptomycin, as previously described (51). Water used for medium and growth factor preparations was purified using the Milli-Q deionization system. The growth medium for stock cultures of MDCK and M1 cells (medium K-1) consisted of DME/F12 further supplemented with 5 μg/ml bovine insulin, 5 μg/ml human transferrin, 5 × 10−12 M triiodothyronine (T3), 5 × 10−8 M hydrocortisone, 25 ng/ml PGE1, and 5 × 10−8 M selenium. Primary cultures of rabbit RPT cells were initiated from rabbit kidneys after euthanization of the animals, following a protocol submitted to and approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, as previously described (12). The RPT cell cultures were maintained in DME/F12 supplemented with 5 μg/ml bovine insulin, 5 μg/ml human transferrin, 5 × 10−8 M hydrocortisone, penicillin, and 0.01% kanamycin (rather than streptomycin). MDCK, M1, and RPT cell cultures were subcultured using 0.53 mM EDTA/0.05% trypsin in PBS (EDTA/trypsin), followed by inhibition of trypsin action with a soybean trypsin inhibitor, as previously described (51). Primary cultures were passaged on a 1:2 basis to obtain first-passage cultures.

Isolation of lentiviral transformants of MDCK cells and stably transfected MDCK cells.

MDCK cells in six-well plates (105 cells/well) were transduced in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene with lentiviral particles (105 TU/well) containing the pLKO.1 vector with either 1) EP1 shRNA, 2) EGFR shRNA, or 3) the empty vector. Subsequently, the cultures were replated at 5 × 104 cells/60-mm dish into medium K-1. The next day the medium was changed to medium K-1 supplemented with 2 μg/ml puromycin. Ten days later, surviving transformants were replated at 500 cells/60-mm dish into medium K-1. Individual clones grown with 2 μg/ml puromycin were isolated with cloning cylinders and expanded in medium K-1 containing 2 μg/ml puromycin.

To obtain dominant negative EGFR transformants, MDCK cells (2 × 105 cells/60-mm dish) were transfected using Lipofectamine with the dominant negative EGFR vector (i.e., HER CD533 in pcDNA3) or the empty vector (pcDNA3). Two days later, the cultures were replated at 5 × 105 cells/60-mm dish into medium K-1. The next day, the medium was changed to medium K-1 containing 0.4 mg/ml G418. After 10 days of selection, surviving clones were isolated with cloning cylinders and expanded in medium K-1 containing 0.4 mg/ml G418.

Growth studies.

Cultures to be used for growth studies were washed twice with PBS and incubated with EDTA/trypsin. After detachment, a soybean trypsin inhibitor was added. The cells were resuspended in PBS and counted in a Coulter counter. At the initiation of the growth study, MDCK cells were inoculated at 103 cells/dish into culture dishes containing DME/F12 supplemented with 5 μg/ml bovine insulin, 5 μg/ml human transferrin, and other effector molecules, as described in the experiment. The cultures were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2-95% air environment for 6 days, unless otherwise stated. After 6 days, the cells were removed from the culture dishes with EDTA-trypsin and counted in a Coulter counter. The average cell number in each experimental condition was calculated from triplicate determinations. The control cell number was the average cell number present in cultures grown in DME/F12 supplemented with 5 μg/ml insulin and 5 μg/ml transferrin, unless otherwise stated.

In the growth studies with MDCK cells with ibuprofen, ibuprofen concentrations were employed that inhibit PGE2 biosynthesis >85%, by RIA (13). In growth studies with first-passage (P1) rabbit RPT cells, the cells were plated at 1.8 × 104 cells/35-mm dish, while in the growth studies with M1 cells, M1 cells were plated at 103 cells/60-mm dish. To study colony formation by M1 cells, the cells were plated at 250 cells/dish. After 10 days in culture, cultures were washed with PBS, incubated with formalin for 5 min, and stained with crystal violet. Colonies were photographed with a Canon Powershot A630 camera. The number of colonies in each condition was averaged from triplicate determinations.

Treatment of cell cultures with effector molecules for Western blot analyses.

To determine the effects of growth factors on protein phosphorylation, MDCK cell cultures were plated at 2 × 105 cells/35-mm dish into dishes containing DME/F12 supplemented with 5 μg/ml insulin and 5 μg/ml transferrin (or 5 μg/ml transferrin alone for the study of pAkt). Two days later, the medium was changed to DME/F12 supplemented with 5 μg/ml insulin and 5 μg/ml transferrin (or 5 μg/ml transferrin alone for the study of pAkt), and the cultures were once again incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% air humidified environment for 2 h, followed by the addition of effector molecules. The cultures were then maintained in the incubator for specified times.

Preparation of cell lysates for electrophoresis.

At the end of the incubation period, the monolayers were washed with ice-cold PBS at 4°C and solubilized at 4°C in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (RIPA), as well as protease and phosphatase inhibitors, including 1 mM PMFS, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mM Na+ orthovanadate and 1 mM NaF. Cell lysates were removed from the dishes with a rubber policeman and transferred into microfuge tubes at 4°C.

Western blot analysis.

Samples were equalized with regard to protein, based upon Bradford protein determinations (7), and separated by electrophoresis through 7.5% SDS/polyacrylamide gels, in parallel with molecular weight markers. The proteins in the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose using a Trans-Blot Apparatus (Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked 1 h in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TTBS), followed by a 2-h incubation with primary antibody in TTBS. Subsequently, the blots were washed six times with TTBS (10 min/wash), followed by a 45-min incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated-secondary antibody. After the incubation with a secondary antibody, the blots were washed seven times with TTBS (15 min/wash). Finally, blots were incubated with Immun-Star HRP Luminol/Enhancer (Bio-Rad), and bands were visualized using LucentBlue X-ray film. Blots probed initially with a primary antibody of interest were subsequently reprobed with an antibody against a loading control such as β-actin. In the case of anti-pAkt antibody, blots were reprobed with anti-Akt antibody. X-ray films of the blots were scanned with a Bio-Rad scanning densitometer, and the relative band intensity was quantitated using the Quantity One Program.

Calculation of results of growth studies and statistics.

The average cell number in each experimental condition, including the control condition, was divided by the average cell number in the control condition using the Prism 6 Program. Thus the control value was 1, unless otherwise stated. For each experimental condition, the “fold-control cell number” was the ratio obtained by dividing the cell number in each experimental condition by the control cell number, unless otherwise specified. To determine whether differences between conditions were statistically significant, t-tests were conducted using Prism 6 software. Differences were deemed significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Both EP2 and EP4 receptors mediate the growth-stimulatory effect of PGE2.

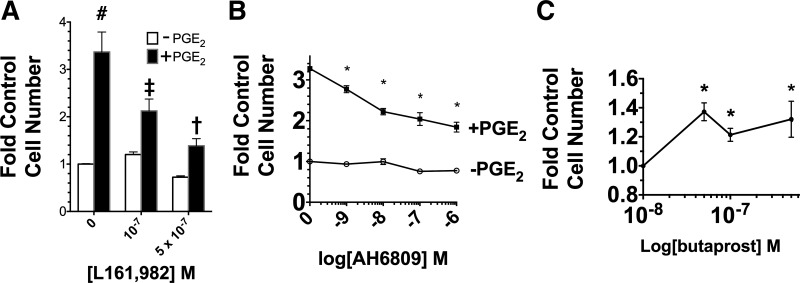

Previously, we reported that PGE1 and PGE2 stimulate MDCK cell growth in defined medium (51). To identify the EP receptors that are involved, the effects of a number of EP receptor-specific agonists and antagonists were examined. Initially, the effect of the EP4 receptor antagonist L161, 982 and the EP2 receptor antagonist AH6809 on the growth-stimulatory effect of PGE2 was examined. Figure 1A shows that L161, 982 inhibited the PGE2 stimulation by 2.4-fold at 5 × 10−7 M. AH6809 also inhibited the PGE2 stimulation, as shown in Fig. 1B. The involvement of EP2 was examined further using an EP2-specific agonist. Figure 1C shows a significant growth-stimulatory effect of butaprost at concentrations ranging from 5 × 10−8 to 5 × 10−7 M.

Fig. 1.

Role of EP2 and EP4 in mediating the growth response to PGE2. A: effect of EP4 antagonist L161, 982 (0, 0.1, 0.5 µM) on growth in the presence or absence of 70 nM PGE2. The control is the value obtained with 0 L161, 982-PGE2. #P < 0.05 relative to control. ‡P < 0.05 relative to cultures grown without PGE2 but in the presence of 10−7 M L161,982. †P < 0.05 relative to cultures grown without PGE2, but in the presence of 5 × 10−7 M L161, 982. B: effect of EP2 antagonist AH6809 (0–10−6 M) on growth in the presence and absence of 70 nM PGE2. The control is the cell number obtained without both PGE2 and AH6809. *P < 0.05 relative to the cell number obtained without PGE2 at the same AH6809 concentration. C: effect of EP2 agonist butaprost (0–10−6 M) on growth. The cells in the cultures were counted after 6 days. Values are the averages ± SE of triplicate determinations. *P < 0.05 relative to the control number obtained in the absence of butaprost.

Role of EP1 receptors: effect of SC51089 and ONO-8711.

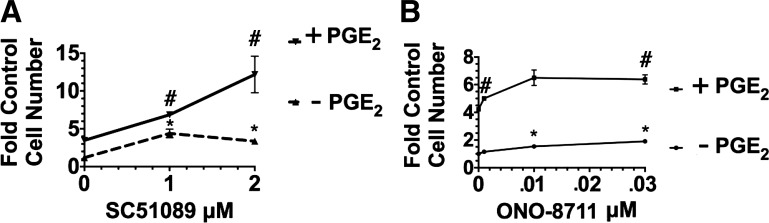

To determine whether Gq-coupled EP1 is also involved, the effect of the EP1 antagonist SC51089 was examined in two different culture conditions, including 1) medium supplemented with insulin and transferrin, while lacking PGE2; and 2) medium further supplemented with 70 nM PGE2. Figure 2A shows results when cultures were grown in the control condition (lacking PGE2). SC51089 was added at the beginning of the growth study, along with the other supplements. Under these conditions, 2 μM SC51089 increased growth 1.8 ± 0.1-fold in the absence of PGE2 (relative to the control value in medium lacking PGE2). Similarly, 70 nM PGE2, increased MDCK cell growth 2.2 ± 0.2-fold relative to the control condition (i.e., the culture condition lacking PGE2 and SC51089). MDCK cell growth increased even further when 2 μM SC51089 was present as well as PGE2 [growth increased 3.2 ± 0.2-fold relative to control (lacking PGE2) and 1.8 ± 0.1-fold relative to cultures grown with PGE2 but in the absence of SC51089]. These results can be explained if 1) EP1 receptor activation results in growth inhibition (rather than a stimulation of growth), and 2) SC51089 prevents the growth inhibition caused by EP1 receptor activation, by preventing the interaction of PGE2 with EP1. Consistent with this hypothesis, Fig. 2B shows that another EP1 antagonist, ONO-8711, increased MDCK cell growth both in the presence of PGE2 (a 2.2 ± 0.3-fold increase relative to cultures with PGE2 and lacking ONO-8711) as well as in the absence of PGE2 [a 1.9 ± 0.1-fold increase relative to control MDCK cells (grown in the absence of both ONO-8711 and PGE2)].

Fig. 2.

Effect of EP1 antagonist SC5108 on Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell growth. A: effect of SC51089 (0,1, and 2 μM) on growth in the presence and absence of 70 nM PGE2. B: effect of ONO-8711 (0–30 nM) on MDCK cell growth in the presence and absence of 70 nM PGE2. The cells in the cultures were counted after 10 days. Values are the averages ± SE of triplicate determinations relative to the control value, i.e., the cell number obtained in the absence of both PGE2 and EP1 antagonist. In A and B, #P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained in the presence of PGE2 but in the absence of EP1 antagonist. *P < 0.05 relative to the control value (obtained in the absence of PGE2).

Effect of EP1 knockdown on the ONO-8711 stimulation.

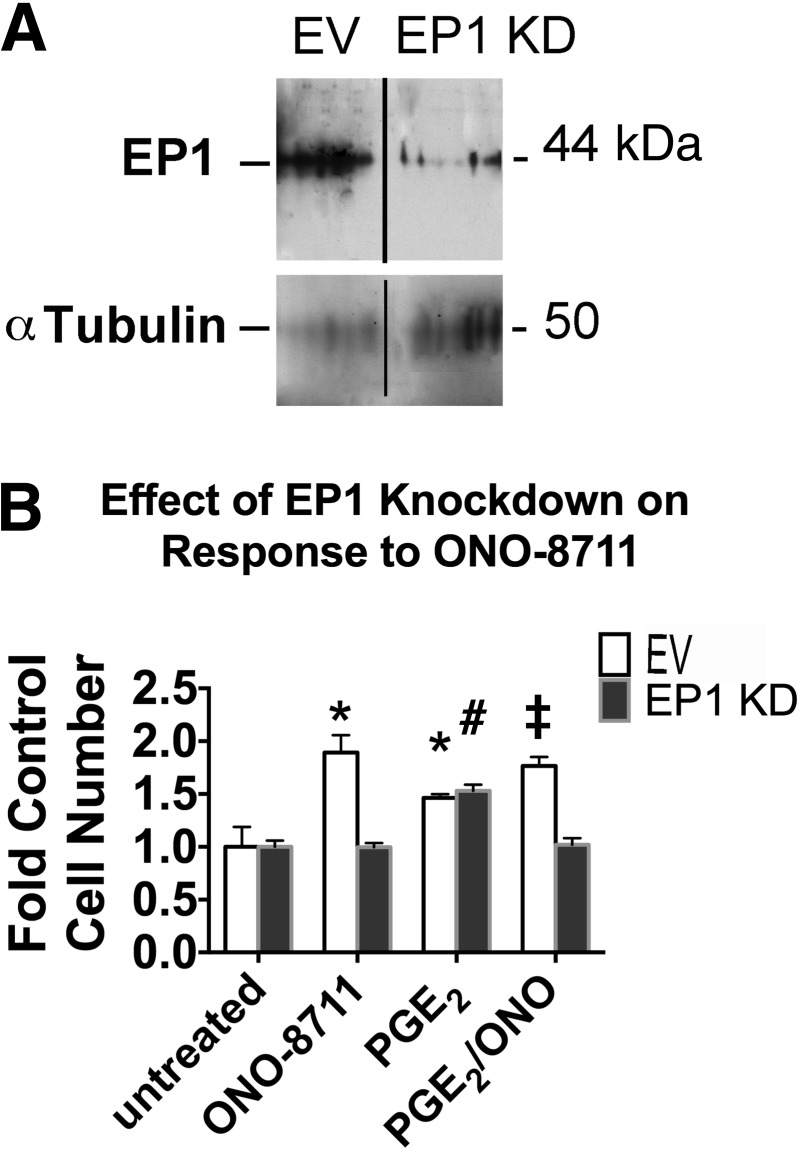

To determine whether the stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 is indeed to due its interaction with the EP1 receptor (thereby preventing EP1 activation by PGE2), MDCK cells were transduced with lentiviral particles containing the pLKO.1 expression vector with EP1 shRNA, in parallel with transductions with the empty vector pLKO.1. Figure 3A shows the expression of the 41.8-kDa EP1 receptor in MDCK cells transduced with the empty vector. In MDCK cells with EP1 shRNA, the level of the EP1 receptor was reduced by 82 ± 1%, compared with MDCK with the empty vector.

Fig. 3.

Effect of EP1 knockdown (KD). A: Western blot showing EP1 protein in MDCK cells transduced with either pLKO (empty vector; EV) or pLKO.1 with EP1 shRNA (EP1 KD), as well as the level of α-tubulin (a loading control). Lanes have been rearranged to show the 2 cell types as adjacent. B: effect of an EP1 KD on the growth response to ONO-8711. The effect of 30 μM ONO-8711, 70 nM PGE2 as well as 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 in combination on growth was examined in MDCK cells transduced either with a lentivirus containing the EV, pLKO.1, or with lentivirus containing EP1 short hairpin (sh) RNA (EP1 KD). *P < 0.05 relative to the EV control (i.e., untreated). ‡P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with PGE2 in MDCK cells transduced with the EV. #P < 0.05 relative to the control value (i.e., untreated) obtained with MDCK cells expressing EP1 shRNA (EP1 KD).

The effect of ONO-8711 on growth was examined in MDCK cells with this EP1 knockdown (KD), relative to MDCK cells with the empty vector. Figure 3B shows that in the absence of PGE2 30 nM ONO-8711 caused a 1.9 ± 0.2-fold increase in the growth of MDCK cells transduced with the empty vector relative to untreated, control EV-MDCK cells. In the presence of PGE2, a 1.8 ± 0.1-fold increase in growth was also observed in MDCK cells with the empty vector (relative to the growth obtained with PGE2 alone). In contrast, a significant growth stimulatory effect of 30 nM ONO-8711 was not observed in MDCK cells with lentiviral EP1 shRNA, when they were maintained either in the presence of PGE2 or in the absence of PGE2. These results support the hypothesis that the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 is a consequence of its interaction with the EP1 receptor.

Studies with M1 collecting duct cells and rabbit RPT cells.

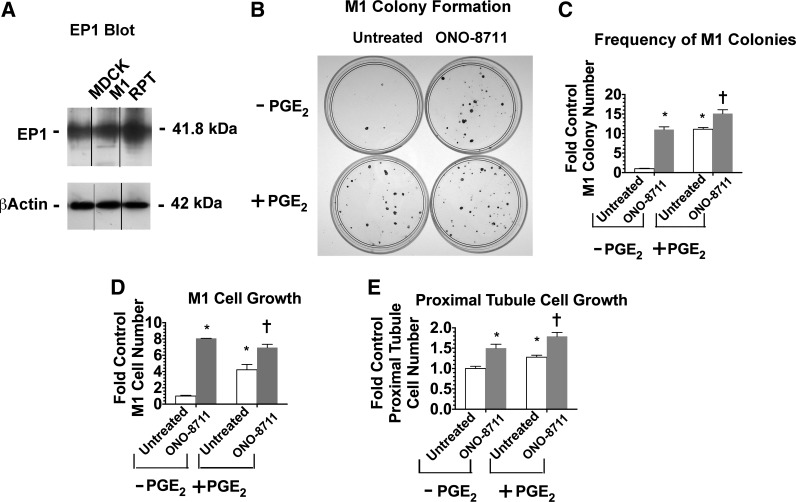

To determine whether the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 is a common property shared by other kidney tubule epithelial cell culture systems, two additional kidney cell culture systems were examined, including the mouse M1 cortical collecting duct cell line and primary rabbit RPT cells. Figure 4A shows that the EP1 receptor is expressed in M1 cells at a level equivalent to that observed in MDCK cells, while in primary RPT cells EP1 expression is 1.5-fold higher.

Fig. 4.

Effect of ONO-8711 on the growth of mouse M1 collecting duct cells and rabbit kidney proximal tubule cells. A: expression of EP1 receptor in MDCK, M1, and primary rabbit renal proximal tubule (RPT) cells. The expression of the EP1 receptor is shown in a Western blot of MDCK cells, M1 mouse collecting duct cells, and primary rabbit RPT cells. Bands have been rearranged to show the 3 cell types as adjacent. β-Actin is shown as a loading control. B: colony formation by mouse M1 collecting duct cells. M1 collecting duct cells were plated at a low density (250 cells/dish) either in control medium (supplemented with insulin and transferrin) or in control medium further supplemented with 30 nM ONO-8711, 70 nM PGE2, or 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 in combination. Subsequently, colony formation by mouse M1 collecting duct cells was visualized by crystal violet staining, as described in materials and methods. C: effect of ONO-8711 on the frequency of colony formation by mouse M1 collecting duct cells. The number of colonies was determined in M1 cell cultures maintained as described above. D: effect of ONO-8711 on M1 cell growth. M1 cell growth was examined (vs. untreated cultures) both in the presence of 70 nM PGE2, and in the control condition (i.e., in the absence of PGE2). E: effect of ONO-8711 on proximal tubule cell growth. Proximal tubule cell growth was examined under the conditions described in above. Values are averages ± SE of triplicate determinations. *P < 0.05 relative to the untreated control. †P < 0.05 relative to untreated cultures maintained with PGE2.

The effect of 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 on colony formation as well as the growth of M1 cells was examined. As shown in Fig. 4, B and C, 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 both increased the number of M1 colonies significantly relative to cultures in the control condition [that is, cultures that were not treated with Ono-8711 (i.e., that were untreated and without PGE2); 11.1 ± 0.7- and 11.1 ± 0.5-fold, respectively]. ONO-8711 also significantly increased the number of M1 colonies in the presence of PGE2 (1.4 ± 0.1-fold relative to cultures with PGE2 alone). As shown in Fig. 4D, 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 similarly increased the overall growth of M1 cells [8.1 ± 0.0- and 6.9 ± 0.4-fold, respectively, relative to the control value (i.e., the average number obtained with untreated M1 cells without PGE2)]. When ONO-8711 was added with PGE2, ONO-8711 also significantly increased growth above the level obtained in the presence of PGE2 alone.

The effect of ONO-8711 and PGE2 on the growth of rabbit RPT cells was also studied. As shown in Fig. 4E, 30 nM ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 both significantly increased the growth of rabbit RPT cells when added individually (a 1.5 ± 0.05- and 1.2 ± 0.05-fold increase, respectively, relative to the control value, i.e., the value in untreated cultures without PGE2). A further increase was observed when ONO-8711 was added in the presence of PGE2 (1.4 ± 0.1-fold relative to the PGE2 control). Thus these results indicate that the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 is not a response specific to the MDCK cell line but instead is a more generalized characteristic of cultured kidney tubule epithelial cells.

Effect of ibuprofen on ONO-8711 stimulation.

The studies described above suggest that EP1 antagonists may alleviate growth inhibition caused by EP1 receptors both in the presence and in the absence of exogenous PGE2. Presumably, EP1 receptor-mediated growth inhibition in the absence of exogenous PGE2 is a consequence of endogenously produced PGE2.

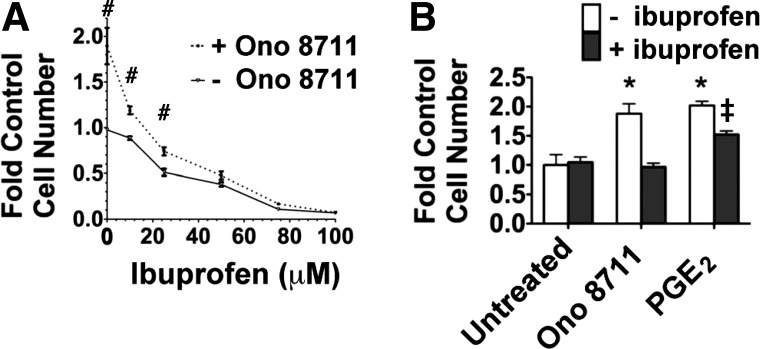

To evaluate this hypothesis, the effect ONO-8711 was studied in the presence of increasing concentrations of ibuprofen, a cyclooxygenase (COX) 1,2 inhibitor (in the absence of exogenous PGE2). Figure 5A shows that the ONO-8711 stimulation was gradually lost, as the ibuprofen concentration was increased to 100 μM. The effect of exogenous PGE2 on growth was also examined in the presence of ibuprofen, because the growth stimulation caused by effectors (such as ONO-8711) may possibly be lost as a consequence of nonspecific inhibitory effects of ibuprofen on EP receptor signaling. Figure 5B shows that PGE2 (0.070 μM) was still growth stimulatory in the presence of ibuprofen (relative to untreated MDCK cells with ibuprofen).

Fig. 5.

Effect of ibuprofen on the growth response to ONO-8711. A: effect of increasing concentrations of ibuprofen (0–100 μM) on growth in the presence and absence of 30 nM ONO-8711. The cells were counted after 8 days in culture. #P < 0.05 relative to the control value (i.e., the value obtained in the absence of both ONO 8711 and ibuprofen). B: effect of ONO-8711 and 70 nM PGE2 on growth, either in the presence or the absence of 100 μM ibuprofen. The cells were counted after 5 days in culture. Values are the averages ± SE of triplicate determinations. *P < 0.05 relative to the control value (i.e., the value obtained with untreated cells grown in the absence of ibuprofen). ‡P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with untreated cells grown in the presence of ibuprofen.

Thus these results can be interpreted as indicating that the growth-stimulatory effects of ONO-8711 are lost when EP1 receptors were no longer activated by PGE2. Therefore, these results support the hypothesis that the increased growth caused by ONO-8711 was due to the ability of ONO-8711 to block the interaction of PGE2 with EP1 receptors, thereby preventing growth inhibition caused by EP1 receptor activation.

Involvement of Akt in mediating the effect of ONO-8711 and insulin.

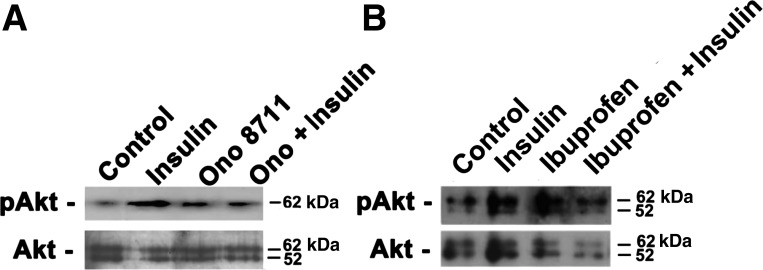

EP1 receptor antagonists reportedly cause activation of Akt in hippocampal slices in vitro (62). Similarly, insulin as been reported to cause the phosphorylation and activation of Akt in mammalian systems (24). Thus the involvement of Akt in mediating the effects of insulin and ONO-8711 in MDCK cells was examined by Western blot analysis. Figure 6A shows that the level of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) increased following a 30-min incubation with either 5 μg/ml insulin or 30 nM ONO-8711 (by 4.4 ± 0.3, and 1.9 ± 0.1-fold, respectively). The level of pAkt did not increase further when insulin and ONO-8711 were added in combination. The latter results may be explained if 1) the growth-stimulatory effects of ONO-8711 and insulin depend upon a threshold level of phosphorylation of Akt (without requiring an additive effect), and thus 2) other signaling pathways are involved.

Fig. 6.

Effect of insulin, ONO-8711, and ibuprofen on Akt phosphorylation. A: the level of pAkt was examined by Western analysis following a 30-min incubation with either control (transferrin alone), 5 μg/ml insulin, 30 nM ONO-8711, or 5 μg/ml insulin and 30 nM ONO-8711 in combination. The level of Akt was also determined. B: effect of no treatment (control; 5 μg/ml transferrin alone), 5 μg/ml insulin, 50 μM ibuprofen, or 5 μg/ml insulin and ibuprofen in combination on the level of pAkt and Akt was similarly determined.

The effect of ibuprofen on Akt phosphorylation was also studied. Figure 6B shows that the level of pAkt increased 2.4 ± 0.1-fold in the presence of ibuprofen. This latter observation can be explained if ibuprofen (like ONO-8711) prevents the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation, resulting from EP1 activation by endogenous PGE2.

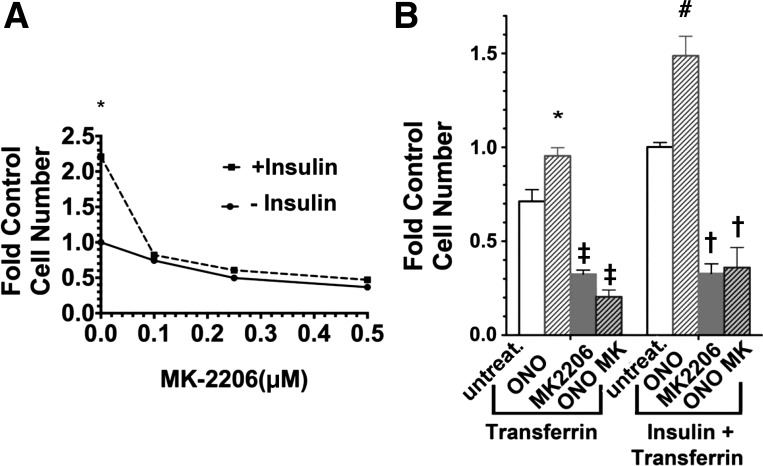

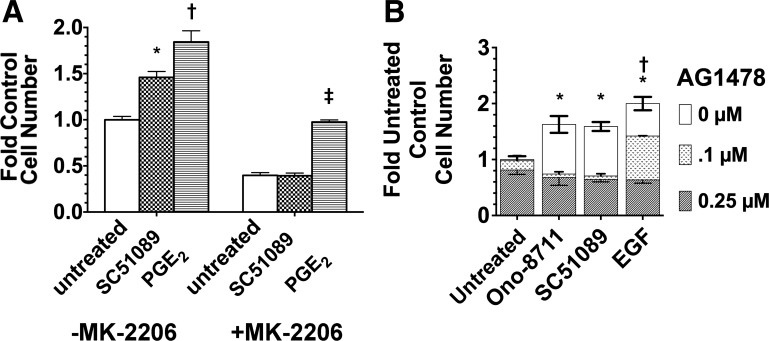

To examine the involvement of Akt in the growth response to insulin and ONO-8711, further studies were conducted with the Akt inhibitor MK-2206. Figure 7A shows that the growth-stimulatory effect of insulin was lost as the MK-2206 concentration was increased to 0.5 μM. Figure 7B shows that in addition 1 μM MK-2206 completely inhibited the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 (in the presence, as well as in the absence of insulin), in addition to reducing growth overall. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the growth-stimulatory effects of both insulin and ONO-8711 are mediated, at least in part, via Akt.

Fig. 7.

Dependence of the growth-stimulatory effect of insulin and ONO-8711 upon MK-2206. A: effect of MK-2206 on MDCK cell growth was studied in both the presence and absence of 1 μg/ml insulin. The control value is the average cell number obtained in the absence of both insulin and MK-2206. *P < 0.05 for the value obtained in the presence of insulin relative to the value at the same MK-2206 concentration in the absence of insulin. B: effect of either 0 nM ONO-8711 (untreat), 30 nM ONO-8711 (ONO), 0.5 μM MK2206, or 0.5 μM MK2206+30 nM ONO-8711 (ONO MK) was examined in medium supplemented with 5 μg/ml transferrin, or in medium supplemented with 5 μg/insulin+5 μg/ml transferrin. The control value is the average cell number obtained with insulin and transferrin alone. With respect to the stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 observed in B, *P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with untreated cultures grown with transferrin alone and #P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with untreated cultures grown with insulin+transferrin, With respect to the inhibitory effects of MK2206, ‡P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with untreated cultures maintained with transferrin alone and †P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with untreated cultures grown with insulin+transferrin alone.

Dependence of the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 upon insulin and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

The studies described above indicate that the growth-stimulatory effects of both ONO-8711 and insulin are dependent upon Akt. Thus the hypothesis was investigated that the cellular response to ONO-8711 was dependent upon insulin, and for this was Akt dependent.

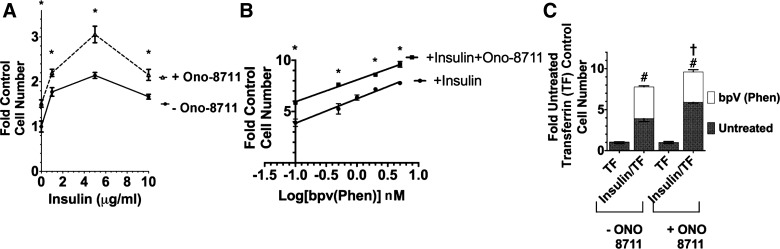

To evaluate this hypothesis initially, the dependence of the ONO-8711 stimulation upon insulin concentration was studied. Transferrin was present alone in these experiments in the control condition, because the effect of insulin itself was being studied (unlike the other growth studies described above, where serum-free medium was supplemented with both 5 μg/ml insulin as well as 5 μg/ml transferrin in control). Figure 8A shows a significant growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711, even in the absence of insulin (1.5 ± 0.1-fold vs. the control value, without ONO-8711 and without insulin). However, ONO-8711 had a maximal growth-stimulatory effect in the presence of 5 μg/ml insulin (the insulin concentration that causes a maximal growth-stimulatory effect on MDCK cells) (51).

Fig. 8.

Dependence of the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 upon insulin and PTEN. A: influence of insulin (0–10 μg/ml) on growth in the presence of either 0 or 30 nM ONO-8711. The control value is the average cell number in the absence of both insulin and ONO-8711. *P < 0.05 relative to the value at the same insulin concentration in the absence of ONO-8711. B: effect of 0–7.5 nM bpV(phen) on MDCK cell growth in the presence and absence of 30 nM ONO-8711. The effect of pbV(phen) was examined between 0.1 and 10 μM. Values are relative to the control value (i.e., the cell number obtained in the presence of insulin and transferrin alone). The best fit line to the data was obtained by linear regression analysis. *P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained in the absence of ONO-8711 at the same bpv(phen) concentration. C: dependence of the effect of 7.5 nM bpv(phen) upon insulin. The effect of bpv(phen), open bars, was examined (vs. untreated MDCK cells, filled bars) either in 1) medium supplemented with 5 μg/ml transferrin alone (TF) or 2) medium supplemented with both 5 μg/ml insulin and 5 μg/ml transferrin (insulin/TF). The effect of 30 nM ONO-8711 was also examined in each of these latter 2 culture conditions. Values were compared with the control value obtained in untreated MDCK cells grown with transferrin alone and in the absence of ONO-8711. #P < 0.05 in the presence of bpv(phen) relative to the value obtained with insulin and transferrin in the absence of ONO-8711. †P < 0.05 relative to the value obtained with insulin and transferrin in the presence of ONO-8711.

Insulin, like a number of growth factors, activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which produces PtdIns (3,4,5) P3, so as to initiate a growth response (1). Activation of PI3K is limited by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), which dephosphorylates PtdIns (3,4,5) P3, and in this manner limits the effect of PI3K. To determine whether the growth-stimulatory effect of insulin and ONO-8711 in MDCK cells involves PTEN (and thus PI3K), the effect of the PTEN inhibitor bpV(phen) was examined.

Figure 8B shows the stimulatory effect of bpV(phen) on MDCK cell growth as a function of bpV(phen) concentration. The amplitude of the growth-stimulatory effect of bpV(phen) continued to increase as the bpV(phen) concentration was increased to 7.5 nM. The growth-stimulatory effect of bpV(phen) was observed in medium supplemented with insulin, as well as in medium supplemented with ONO-8711 and insulin. However, the overall magnitude of the bpV(phen) stimulation did not increase significantly when ONO-8711 was present in addition to insulin. The slope of the best-fit line to the experimental results obtained in the absence of ONO-8711 was a “2.4 ± 0.2-fold increase (relative to the control cell number)/log[nmoles bpv(phen)].” The slope of the best-fit line to the experimental results did not change significantly in the presence of ONO-8711.

As shown in Fig. 8C, the growth-stimulatory effect of bpV(phen) was not observed in the absence of insulin (even when ONO-8711 was present). Thus the increased growth caused by the PTEN inhibitor bpV(phen) can be attributed to the ability of bpV(phen) to increase the growth response to insulin, irrespective of the presence of ONO-8711. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 does not depend upon PI3K but instead is a consequence of signaling events occurring downstream from PI3K.

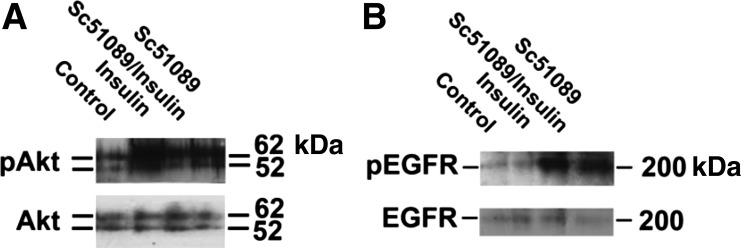

Role of Akt and the EGFR in mediating the response to SC51089.

The effect of the EP1 antagonist SC51089 on Akt phosphorylation was also examined. Figure 9A shows that the level of phospho-Akt increased 7 ± 1- and 13 ± 1-fold following a 30-min incubation with either SC51089 or insulin, respectively. The level of Akt phosphorylation did not increase further when SC51089 and insulin were added in combination. Previously, the EP1 receptor was reported to transactivate the EGFR, increasing the phosphorylation of the EGFR (22). Thus the effect of SC51089 on EGFR phosphorylation was examined. Figure 9B shows that the level of phospho-EGFR increased 4.8 ± 0.2-fold in the presence of SC51089 (P < 0.05), unlike the case with insulin.

Fig. 9.

Effect of insulin and SC51089 on the phosphorylation of Akt and the EGF receptor (EGFR). MDCK cells were incubated for 30 min with either no further supplement (i.e., control, 5 μg/ml transferrin alone), 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml insulin and 2 μg/ml SC51089 in combination, or 2 μM SC51089. Level of pAkt and Akt (A) pEGFR and EGFR (B) in the samples was examined by Western blot analysis.

To further examine the role of Akt and the EGFR in mediating the growth response to SC51089, the Akt inhibitor MK-2206 and the EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 were studied. Figure 10A shows that MK-2206 prevented the SC51089-mediated increase in MDCK cell growth, while the growth-stimulatory effect of PGE2 remained (indicating involvement of another mechanism). Figure 10B shows that AG1478 (at either 0.1 or 0.25 μM) inhibited the growth-stimulatory effects of both SC51089 and ONO-8711. However, 0.1 μM AG1478 only partially inhibited the growth-stimulatory effect of EGF, 0.25 μM AG1478 being required for a complete inhibition of the growth-stimulatory effect of EGF.

Fig. 10.

Effect of Akt inhibitor MK-2206 and EGFR inhibitor AG1478 on the growth response to EGFR antagonists. A: effect of 2 μM SC51089 and 70 nM PGE2 on growth, relative to untreated MDCK cell cultures, was examined both in the presence of 0.5 μM MK-2206 and in the absence of MK-2206 (control). *P < 0.05 relative to the values in untreated cultures lacking MK-2206 (i.e., the control value). †P < 0.05 relative to the value in cultures with SC51089, but lacking MK-2206. ‡P < 0.05 relative to untreated MK-2206. B: effect of AG1478. The influence of 0, 0.1, and 0.25 μM AG1478 on MDCK cell growth was examined in the untreated condition (i.e., in medium supplemented with insulin and transferrin), as well as in culture medium further supplemented with either 30 nM Ono-8711, 2 μM SC51089, or 5 ng/ml EGF. Average values in each condition were compared with the control value (i.e., the average cell number obtained in the untreated condition lacking AG1478). *P < 0.05 relative to control lacking AG1478. †P < 0.05 in the presence of 0.1 μM AG1478 relative to the untreated control.

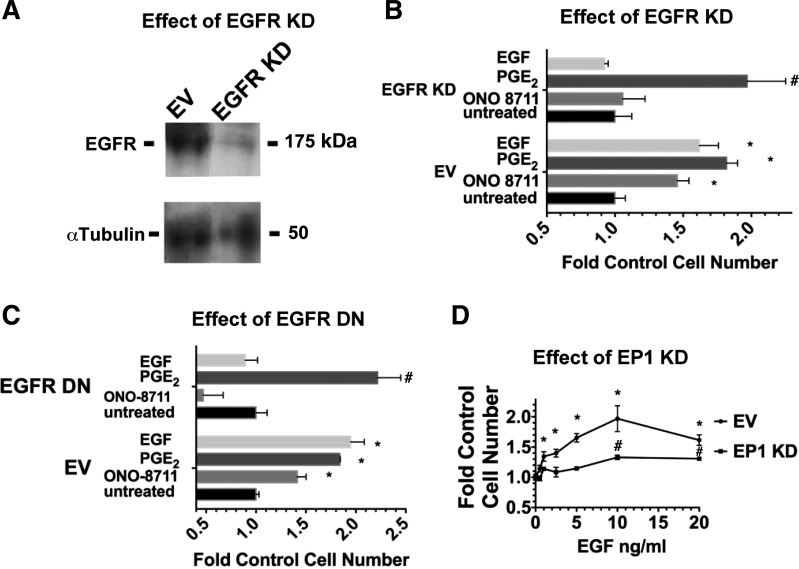

To further evaluate whether EGFR activation is required to obtain a growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711, growth studies were conducted with MDCK cells that had been transduced with a lentivirus containing pLKO.1 with shRNA against the EGFR. As shown in Fig. 11A, the level of the EGFR was reduced by 94 ± 2% in MDCK cells transduced with EGFR shRNA (i.e., MDCK cells with an EGFR KD). Figure 11B shows that ONO-8711 and EGF were not growth stimulatory to MDCK cells with an EGFR KD, unlike their growth-stimulatory effects observed in MDCK cells transduced with pLKO.1 (i.e., the empty vector in this experiment).

Fig. 11.

Genetic studies indicating the involvement of the EGFR and the EP1 receptor in the growth response to ONO-8711, and EGF, respectively. A: effect of an EGFR KD on expression of the EGFR. A Western blot shows expression of the EGFR in MDCK cells transduced with lentiviral pLKO.1 (EV), or with EGFR shRNA. α-Tubulin is shown as a loading control. B: effect of an EGFR KD on growth. The effect of 30 nM ONO-8711, 70 nM PGE2, and 5 ng/ml EGF on growth was examined both in MDCK cells transduced with lentivirus containing either the EV (pLKO.1) or pLKO.1 with shRNA against the EGFR. The control value was the average cell number in untreated cultures for each cell type. C: effect of dominant negative (DN) EGFR on growth. The effect of 30 μM ONO-8711, 70 nM PGE2, and 5 ng/ml EGF on growth was examined (vs. untreated controls) in MDCK cells selected for expression of either a dominant negative EGFR or pcDNA3 (EV). The control value was the average cell number in untreated cultures for each cell type. D: effect of EP1 KD on the growth response to EGF. The effect of EGF (0- 20 ng/ml) on growth was examined in MDCK cells transduced with lentivirus containing either the EV (pLKO.1) or pLKO.1 with shRNA against the EP1 receptor. The control value was the average cell number obtained in untreated cultures (in the absence of EGF) for each cell type. In B, C and D, MDCK cell cultures were counted after 6 days in culture. Values are averages ± SE of triplicate determinations. *P < 0.05 relative to the control value of MDCK cells transduced with EV. #P < 0.05 relative to the control value of MDCK cells transduced with either lentiviral EGFR shRNA, EGFR DN, or EP1 shRNA.

Growth studies were also conducted with HERCD533- MDCK cells, permanently expressing a vector (pcDNA3) encoding for a dominant negative EGFR (HERCD533), which prevents EGFR-mediated signaling (26). Figure 11C shows that HERCD533-MDCK cells lack the growth-stimulatory effect of EGF, unlike MDCK cells which permanently express the empty vector (EV-MDCK), pcDNA3. Figure 11C also shows that HERCD533-MDCK cells lack the growth-stimulatory response to ONO-8711, unlike the EV-MDCK. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that EGFR activation is required to elicit the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711.

To determine whether the growth response to EGF is similarly dependent upon the EP1 receptor, the effect of increasing concentrations of EGF (0–20 ng/ml) on the growth on MDCK cells with an EP1 knockdown was examined in parallel with MDCK cells with pLKO.1 (EV-MDCK cells). As shown in Fig. 11D, EGF increased the growth of EV-MDCK cells as high as 2.0 ± 0.2-fold (at 10 ng/ml EGF), as the EGF concentration was increased to 20 ng/ml. In contrast, Fig. 11D shows that in MDCK cells with an EP1 KD, the maximum stimulation obtained with EGF was 1.3 ± 0.04-fold (also at 10 ng/ml EGF). These observations suggest that signaling via the EGFR is indeed dependent upon the EP1 expression level in MDCK cells.

DISCUSSION

Activation of the EP1 receptor has been associated with the progression of a number of renal disease states (3, 31, 43, 48), unlike the EP2 and EP4 receptors, whose activation has been found to be protective (2, 56, 57). Indeed, the EP1 antagonist ONO-8713 decreased renal damage in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRSPs) (48). In addition, ONO-8713 reduced mesangial expansion, as well as glomerular and tubular hypertrophy, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (36). Renal functions which may be affected under these conditions include Na+ transport and vasoconstriction (28, 42). In contrast, EP4 receptor activation reduced glomerular sclerosis and increased the proliferation of proximal convoluted epithelial cells in a rat model of chronic renal failure (2, 57). Similarly, the activation of both EP2 and EP4 receptors increased the survival of distal as well as proximal tubules, in a nephrotoxic mercuric chloride rat model of acute renal failure (57).

Our previous studies indicate that PGE2 is growth stimulatory to MDCK cells, as well as primary cultures of baby mouse kidney epithelial cells in serum-free medium (51, 54). The results presented here support the hypothesis that the growth-stimulatory effects of PGE2 are mediated by Gs-coupled EP2 and EP4 receptors, unlike Gq-coupled EP1 receptors, whose activation results in growth inhibition. Consistent with this hypothesis, AH6809 and L161,982 (antagonists of EP2 and EP4, respectively) inhibited the growth-stimulatory effect of PGE2, unlike the EP1 antagonists ONO-8711 and SC51089, which were growth stimulatory. Consistent with the involvement of EP1 receptors in the growth response to these EP1 antagonists, the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 was not observed in MDCK cells with an EP1 receptor KD.

In our initial studies concerning the growth of MDCK cell cells in hormonally defined medium, we found that five growth supplements, insulin, transferrin, T3, hydrocortisone, and PGE2, permitted MDCK cells to grow at the same rate as in serum-supplemented medium (51). To determine whether the requirement for the five growth supplements was unique to MDCK cells, or was common to other types of kidney tubule epithelial cells, we investigated the ability of the defined medium for MDCK cells to promote the growth of primary cultures of baby mouse kidney epithelial cells (51, 54). Our initial results indicated that primary cultures of baby mouse kidney epithelial cells grew in the defined medium for MDCK cells without fibroblast overgrowth (51). Subsequent studies indicated that the primary cultures of baby mouse kidney epithelial cells grew in response to each of the five supplements in the defined medium for MDCK (54). However, PGE2 and transferrin had larger effects on growth of the primary baby mouse kidney epithelial cells than the other three supplements, similar to the observations made with MDCK.

In this report, PGE2 was similarly observed to be growth stimulatory to mouse M1 collecting duct cells and rabbit RPT cells in defined medium. In addition, ONO-8711 was observed to increase the growth of M1 cells and rabbit RPT cells, as well as MDCK cells. These latter observations suggest that these findings reflect a true in vivo process rather than an aberrant observation made with a single established kidney cell line.

The growth-stimulatory effects of ONO-8711 and SC51089 were observed both in the presence and in the absence of exogenously added PGE2. Presumably, the increased growth caused by these EP1 antagonists in the absence of exogenous PGE2 is due to their ability to block EP1 receptor activation by endogenously produced PGE2. Consistent with this hypothesis, ONO-8711 did not increase MDCK cell growth in the presence of ibuprofen, a COX1 and COX2 inhibitor.

Previously, Kawano et al. (27) reported that EP1 receptor activation was responsible for the neurotoxicity caused by the COX2-derived PGE2, which is produced during cerebral ischemia. The inhibition of EP1 receptor activation was found to provide neuroprotection by a mechanism involving inhibition of PTEN and activation of Akt (62). Our results indicate that the EP1 antagonists ONO-8711 and SC51089 similarly increase the level pAkt in MDCK cells (indicative of Akt activation). Insulin also increased Akt phosphorylation in MDCK cells, presumably as a consequence of the interaction of insulin with the IGF1 and/or IGF2 receptors expressed in MDCK cells (insulin receptors are not present in MDCK) (29). However, when ONO-8711 was added in combination with insulin, no further increase Akt phosphorylation was observed under our experimental conditions. These latter results may nevertheless still be explained by the involvement of pAkt, if the growth-stimulatory effects of ONO-8711 and insulin depend upon the cells achieving a threshold level of Akt phosphorylation. Presumably, under the incubation conditions of the Western blot study, this threshold level was achieved by the addition of insulin alone.

The involvement of Akt as a mediator of the growth-stimulatory effect of ONO-8711 during longer-term incubations is supported by the observation that the Akt inhibitor MK2206 prevented the growth-stimulatory effects of ONO-8711, SC51089, and insulin. The Akt phosphorylation that occurs under these conditions may be initiated by signaling events originating from IGF receptors (which ultimately result in the growth response to insulin). In this case, the EP1 receptor, when activated, would presumably function so as to reduce the Akt phosphorylation (and activation) that occurs in response to insulin and insulin-like growth factors. In this case, EP1 receptor antagonists, including ONO-8711 and SC51089, would act so as to prevent this consequence of EP1 receptor activation.

The increased growth that occurs in response to insulin very likely involves the activation of PI3K, and as a consequence Akt (24). However, other growth-stimulatory factors (such as ONO-8711 and SC51089) may also increase growth by their ability to inhibit PTEN, a regulatory protein which inhibits PI3K (24). Indeed, the PTEN inhibitor bpV(phen) stimulated MDCK cell growth, indicating that PTEN does indeed limit the growth of MDCK cells in serum-free medium. Consistent with this hypothesis, the increased growth observed in the presence of bpV(phen) was dependent upon the presence of insulin in the culture medium, presumably due to a requirement for the activation of PI3K (by insulin). However, the growth-stimulatory effect of bpV(phen) did not increase significantly when ONO-8711 was present in addition to insulin, indicating that ONO-8711 did not cause the further activation of PI3K/PTEN.

The involvement of the EGFR signaling pathway in EP1-mediated growth control in MDCK cells was also indicated in our studies. Interrelationships between EGF and PGE2 have been reported previously in the kidney, where both growth factors are produced in large quantities (5, 45). Following the production of EGF by the kidney, EGF binds to EGFRs, localized on the surface of many types of renal cells (10, 18). One consequence of the activation of the EGFR is the activation of PLA2, and the subsequent production of PGE2, which ultimately affects renal function (32, 37). For example, PGE2, produced in response to EGF in RPT cells, stimulates basolateral organic anion transport (47), while PGE2, produced in response to EGF in mesangial cells, causes decreased expression of cyclin D3, and hypertrophy (43). In addition to stimulating PGE2 production, activation of the EGFR has other functional consequences, including inhibition of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in the collecting duct, unlike PGE2 which targets Na-K-ATPase in this nephron segment (40).

A number of renal hormones and effectors, including arginine vasopressin, aldosterone, and ANG II, “transactivate” the renal EGFR (15, 20, 30). One mechanism for the transactivation is the release of heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), or transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), from the surface of renal cells. The released HB-EGF (and/or TGF-α) subsequently binds to the EGFR, resulting in EGFR phosphorylation and activation. Both HB-EGF and TGF-α can be released from the surface of renal cells following the activation of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) (21, 30). Indeed, ADAM-dependent EGFR transactivation is reportedly induced by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including Gq-coupled receptors. The binding of ligands to such GPCRs has been observed to cause the phosphorylation and activation of ADAM family members, resulting in the release of EGFR ligands from the plasma membrane. This mechanism is of particular concern in polycystic kidney disease (PKD), because the EGFR (normally localized basolaterally) relocalizes to the apical membrane. EGF and related EGFR ligands (released by ADAMs) are present in the lumen of the nephron, where they interact with the apical EGFRs in PKD, activating EGFR signaling pathways, leading to increased growth and Na+ transport (61). Indeed suppression of EGFR transactivation has become a target of therapy in PKD (4).

In MDCK cells, the activation of EP1 receptors apparently results in the inhibition, rather than the activation, of the EGFR. Instead, EGFR activation apparently occurs in response to EP1 antagonists. One possible mechanism of activation (described above) is the release of HB-EGF by ADAMs in response to EP1 antagonism. In this case, activation of EP1 receptors by PGE2 instead results in the inhibition of ADAMs. Indeed, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are inhibitors of ADAMs, and TIMPS may be activated as a consequence of EP1 receptor activation.

EGFR transactivation can also occur independently of the release of HB-EGF by ADAMs. Indeed, the EGFR reportedly interacts with EP1 receptors in other cell types, including human CCLP1 cholangiocarcinoma cells (23). In this case, the affinity of the EGFR for the EP1 receptor is altered by the binding of ligands to the EP1 (23). If this mechanism occurs in MDCK cells, the binding of EP1 antagonists to the EP1 receptor would be expected to cause an increase in EGFR phosphorylation and activation, by altering EGFR/EP1 receptor interaction.

Previous studies have indicated that PGE2 plays a role in promoting cystogenesis in renal tubules. PGE2 is present in cyst fluid of human ADPKD (19) and induces cystogenesis via the activation of EP2 and EP4 receptors (16, 17). As a consequence, increased growth and transport are observed in ADPKD tubular cells (33). PGE2 similarly increases growth and Na+ transport in MDCK cells, as well as chloride secretion in MDCK cells, the murine M-1 cortical collecting duct cell line, and polycystin 1-deficient murine inner medullary collecting duct cells (33, 46, 50, 51, 59). We do not yet know whether these PGE2-mediated signaling events are altered in ADPKD. However, the results presented in this report indicate that EP1 activation dampens EP2- and EP4-mediated proliferative events, which are required for cystogenesis. Activation of EP1 may do so by affecting the Akt and EGFR signaling pathways. In addition, EP1 may also prevent the increased growth that occurs in ADPKD cells by preventing the activation of the B-Raf/Erk pathway that normally occurs in response to cAMP, presumably as a consequence of EP2 and EP4 activation (60). To achieve this cAMP-dependent growth-stimulated phenotype, renal cells must be in a Ca2+-restricted state. However, activation of EP1 raises intracellular Ca2+ (as a consequence of PLC activation), thereby preventing renal cells from achieving the necessary Ca2+-restricted state required for activation of B-Raf/ERK. Further studies are necessary to evaluate these hypotheses.

GRANTS

Funding for this work was obtained from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 1RO1-HK-69676-01 to M. Taub.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.L.T., R.P., P.M., M.A.M.A., and T.R. provided conception and design of research; M.L.T., R.P., P.M., M.A.M.A., and T.R. performed experiments; M.L.T., R.P., P.M., M.A.M.A., and T.R. analyzed data; M.L.T., R.P., P.M., M.A.M.A., and T.R. interpreted results of experiments; M.L.T., R.P., P.M., M.A.M.A., and T.R. prepared figures; M.L.T. drafted manuscript; M.L.T. edited and revised manuscript; M.L.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Sylvain Meloche for the expression vector for the dominant negative EGFR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi DR. Discovery of PDK1, one of the missing links in insulin signal transduction. Colworth Medal Lecture. Biochem Soc Trans 29: 1–14, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoudjit L, Potapov A, Takano T. Prostaglandin E2 promotes cell survival of glomerular epithelial cells via the EP4 receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1534–F1542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett CS, Boyd KL, Harris RC, Zent R, Breyer RM. EP1 disruption attenuates end-organ damage in a mouse model of hypertension. Hypertension 60: 1184–1191, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belibi FA, Edelstein CL. Novel targets for the treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 19: 315–328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonvalet JP, Pradelles P, Farman N. Segmental synthesis and actions of prostaglandins along the nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F377–F387, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottinger EP. TGF-beta in renal injury and disease. Semin Nephrol 27: 309–320, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breyer MD, Breyer RM. G protein-coupled prostanoid receptors and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 63: 579–605, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breyer MD, Breyer RM. Prostaglandin E receptors and the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F12–F23, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breyer MD, Redha R, Breyer JA. Segmental distribution of epidermal growth factor binding sites in rabbit nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F553–F558, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breyer MD, Zhang Y, Guan YF, Hao CM, Hebert RL, Breyer RM. Regulation of renal function by prostaglandin E receptors. Kidney Int Suppl 67: S88–S94, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung SD, Alavi N, Livingston D, Hiller S, Taub M. Characterization of primary rabbit kidney cultures that express proximal tubule functions in a hormonally defined medium. J Cell Biol 95: 118–126, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen-Luria R, Moran A, Rimon G. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress inhibitory effect of PGE2 on Na-K-ATPase in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F94–F98, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devis PE, Grohol SH, Taub M. Dibutyryl cyclic AMP resistant MDCK cells in serum free medium have reduced cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase activity and a diminished effect of PGE1 on differentiated function. J Cell Physiol 125: 23–35, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eiam-Ong S, Sinphitukkul K, Manotham K. Rapid nongenomic action of aldosterone on protein expressions of Hsp90 (alpha and beta) and pc-Src in rat kidney. Biomed Res Int 2013: 346480, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elberg D, Turman MA, Pullen N, Elberg G. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates cystogenesis through EP4 receptor in IMCD-3 cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 98: 11–16, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elberg G, Elberg D, Lewis TV, Guruswamy S, Chen L, Logan CJ, Chan MD, Turman MA. EP2 receptor mediates PGE2-induced cystogenesis of human renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1622–F1632, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher DA, Salido EC, Barajas L. Epidermal growth factor and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 51: 67–80, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner KD, Jr, Burnside JS, Elzinga LW, Locksley RM. Cytokines in fluids from polycystic kidneys. Kidney Int 39: 718–724, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh PM, Mikhailova M, Bedolla R, Kreisberg JI. Arginine vasopressin stimulates mesangial cell proliferation by activating the epidermal growth factor receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F972–F979, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gooz M, Gooz P, Luttrell LM, Raymond JR. 5-HT2A receptor induces ERK phosphorylation and proliferation through ADAM-17 tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE) activation and heparin-bound epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) shedding in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 281: 21004–21012, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han C, Michalopoulos GK, Wu T. Prostaglandin E2 receptor EP1 transactivates EGFR/MET receptor tyrosine kinases and enhances invasiveness in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol 207: 261–270, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han C, Wu T. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2 promotes human cholangiocarcinoma cell growth and invasion through EP1 receptor-mediated activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and Akt. J Biol Chem 280: 24053–24063, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemmings BA, Restuccia DF. PI3K-PKB/Akt pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a011189, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman M, Rajkhowa T, Cutuli F, Springate JE, Taub M. Regulation of renal proximal tubule Na-K-ATPase by prostaglandins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1222–F1234, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashles O, Yarden Y, Fischer R, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. A dominant negative mutation suppresses the function of normal epidermal growth factor receptors by heterodimerization. Mol Cell Biol 11: 1454–1463, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Park L, Wang G, Frys KA, Kunz A, Cho S, Orio M, Iadecola C. Prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptors: downstream effectors of COX-2 neurotoxicity. Nat Med 12: 225–229, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy CR, Xiong H, Rahal S, Vanderluit J, Slack RS, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Breyer MD, Hebert RL. Urine concentrating defect in prostaglandin EP1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F868–F875, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krett NL, Heaton JH, Gelehrter TD. Madin-Darby canine kidney cells display type I and type II insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 134: 120–127, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lautrette A, Li S, Alili R, Sunnarborg SW, Burtin M, Lee DC, Friedlander G, Terzi F. Angiotensin II and EGF receptor cross-talk in chronic kidney diseases: a new therapeutic approach. Nat Med 11: 867–874, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lelongt B, Makino H, Dalecki TM, Kanwar YS. Role of proteoglycans in renal development. Dev Biol 128: 256–276, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine L, Hassid A. Epidermal growth factor stimulates prostaglandin biosynthesis by canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 76: 1181–1187, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Rajagopal M, Lee K, Battini L, Flores D, Gusella GL, Pao AC, Rohatgi R. Prostaglandin E2 mediates proliferation and chloride secretion in ADPKD cystic renal epithelia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1425–F1434, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long CR, Kinoshita Y, Knox FG. Prostaglandin E2 induced changes in renal blood flow, renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure and sodium excretion in the rat. Prostaglandins 40: 591–601, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magri CJ, Fava S. The role of tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Intern Med 20: 551–555, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino H, Tanaka I, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Muro S, Suganami T, Yahata K, Ishibashi R, Ohuchida S, Maruyama T, Narumiya S, Nakao K. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in rats by prostaglandin E receptor EP1-selective antagonist. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1757–1765, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolis BL, Bonventre JV, Kremer SG, Kudlow JE, Skorecki KL. Epidermal growth factor is synergistic with phorbol esters and vasopressin in stimulating arachidonate release and prostaglandin production in renal glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J 249: 587–592, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matlhagela K, Borsick M, Rajkhowa T, Taub M. Identification of a prostaglandin-responsive element in the Na,K-ATPase β1 promoter that is regulated by cAMP and Ca2+: evidence for an interactive role of cAMP regulatory element-binding protein and Sp1. J Biol Chem 280: 334–346, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matlhagela K, Taub M. Involvement of EP1 and EP2 receptors in the regulation of the Na,K-ATPase by prostaglandins in MDCK cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 79: 101–113, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlov TS, Levchenko V, O'Connor PM, Ilatovskaya DV, Palygin O, Mori T, Mattson DL, Sorokin A, Lombard JH, Cowley AW, Jr, Staruschenko A. Deficiency of renal cortical EGF increases ENaC activity and contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1053–1062, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelayo JC, Shanley PF. Glomerular and tubular adaptive responses to acute nephron loss in the rat. Effect of prostaglandin synthesis inhibition. J Clin Invest 85: 1761–1769, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purdy KE, Arendshorst WJ. EP1 and EP4 receptors mediate prostaglandin E2 actions in the microcirculation of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F755–F764, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian Q, Kassem KM, Beierwaltes WH, Harding P. PGE2 causes mesangial cell hypertrophy and decreases expression of cyclin D3. Nephron Physiol 113: p7–p14, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahal S, McVeigh LI, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Breyer MD, Kennedy CR. Increased severity of renal impairment in nephritic mice lacking the EP1 receptor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84: 877–885, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rall LB, Scott J, Bell GI, Crawford RJ, Penschow JD, Niall HD, Coghlan JP. Mouse prepro-epidermal growth factor synthesis by the kidney and other tissues. Nature 313: 228–231, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandrasagra S, Cuffe JE, Regardsoe EL, Korbmacher C. PGE2 stimulates Cl− secretion in murine M-1 cortical collecting duct cells in an autocrine manner. Pflügers Arch 448: 411–421, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sauvant C, Hesse D, Holzinger H, Evans KK, Dantzler WH, Gekle M. Action of EGF and PGE2 on basolateral organic anion uptake in rabbit proximal renal tubules and hOAT1 expressed in human kidney epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F774–F783, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suganami T, Mori K, Tanaka I, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Makino H, Muro S, Yahata K, Ohuchida S, Maruyama T, Narumiya S, Nakao K. Role of prostaglandin E receptor EP1 subtype in the development of renal injury in genetically hypertensive rats. Hypertension 42: 1183–1190, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syal A, Schiavi S, Chakravarty S, Dwarakanath V, Quigley R, Baum M. Fibroblast growth factor-23 increases mouse PGE2 production in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F450–F455, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taub M, Borsick M, Geisel J, Matlhagela K, Rajkhowa T, Allen C. Regulation of the Na,K-ATPase in MDCK cells by prostaglandin E1: a role for calcium as well as cAMP. Exp Cell Res 299: 1–14, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taub M, Chuman L, Saier MH, Jr, Sato G. Growth of Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cell (MDCK) line in hormone-supplemented, serum-free medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 3338–3342, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taub M, Devis PE, Grohol SH. PGE1-independent MDCK cells have elevated intracellular cyclic AMP but retain the growth stimulatory effects of glucagon and epidermal growth factor in serum-free medium. J Cell Physiol 120: 19–28, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taub M, Sato G. Growth of functional primary cultures of kidney epithelial cells in defined medium. J Cell Physiol 105: 369–378, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taub M, Sato GH. Growth of kidney epithelial cells in hormone-supplemented, serum-free medium. J Supramol Struct 11: 207–216, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vennemann A, Gerstner A, Kern N, Ferreiros Bouzas N, Narumiya S, Maruyama T, Nusing RM. PTGS-2-PTGER2/4 signaling pathway partially protects from diabetogenic toxicity of streptozotocin in mice. Diabetes 61: 1879–1887, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vukicevic S, Simic P, Borovecki F, Grgurevic L, Rogic D, Orlic I, Grasser WA, Thompson DD, Paralkar VM. Role of EP2 and EP4 receptor-selective agonists of prostaglandin E2 in acute and chronic kidney failure. Kidney Int 70: 1099–1106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wald H, Scherzer P, Rubinger D, Popovtzer MM. Effect of indomethacin in vivo and PGE2 in vitro on MTAL Na-K-ATPase of the rat kidney. Pflügers Arch 415: 648–650, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wegmann M, Nusing RM. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates sodium reabsorption in MDCK C7 cells, a renal collecting duct principal cell model. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 69: 315–322, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamaguchi T, Wallace DP, Magenheimer BS, Hempson SJ, Grantham JJ, Calvet JP. Calcium restriction allows cAMP activation of the B-Raf/ERK pathway, switching cells to a cAMP-dependent growth-stimulated phenotype. J Biol Chem 279: 40419–40430, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheleznova NN, Wilson PD, Staruschenko A. Epidermal growth factor-mediated proliferation and sodium transport in normal and PKD epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 1301–1313, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou P, Qian L, Chou T, Iadecola C. Neuroprotection by PGE2 receptor EP1 inhibition involves the PTEN/AKT pathway. Neurobiol Dis 29: 543–551, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]