EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Purpose:

To develop an End of Life Care (EOLC) Policy for patients who are dying with an advanced life limiting illness. To improve the quality of care of the dying by limiting unnecessary therapeutic medical interventions, providing access to trained palliative care providers, ensuring availability of essential medications for pain and symptom control and improving awareness of EOLC issues through education initiatives.

Evidence:

A review of Country reports, observational studies and key surveys demonstrates that EOLC in India is delivered ineffectively, with a majority of the Indian population dying with no access to palliative care at end of life and essential medications for pain and symptom control. Limited awareness of EOLC among public and health care providers, lack of EOLC education, absent EOLC policy and ambiguous legal standpoint are some of the major barriers in effective EOLC delivery.

Recommendations:

Access to receive good palliative and EOLC is a human right. All patients are entitled to a dignified death.

Government of India (GOI) to take urgent steps towards a legislation supporting good EOLC, and all hospitals and health care institutions to have a working EOLC policy

Providing a comprehensive care process that minimizes physical and non physical symptoms in the end of life phase and ensuring access to essential medications for pain and symptom control

Palliative care and EOLC to be part of all hospital and community/home based programs

Standards of palliative and EOLC as established by appropriate authorities and Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) met and standards accredited and monitored by national and international accreditation bodies

All health care providers with direct patient contact are urged to undergo EOLC certification, and EOLC training should be incorporated into the curriculum of health care education.

Keywords: End of life care, Indian association of palliative care, Position statement

Intent:

Based on current non-communicable disease, cancer statistics and national as well as international reports, IAPC feels that EOLC in India is delivered ineffectively. The dying Indian population is, at present, receiving no care or inappropriate care at end of life, and patients are dying with pain and distress in an undignified way. IAPC aims to address this problem by advocating for the patients with EOLC needs, identifying gaps in service provision and bridging these gaps by improving awareness, persuading the government to formulate a supportive legislation and EOLC policy, promoting EOLC education in health curricula, creating standards and implementation and monitoring of these standards.

The Position Indian Association of Palliative care (IAPC) takes the position that access to palliative and end of life care (EOLC) is a human right. Therefore everyone with a life limiting illness has a right to a life free from pain, symptoms and distress; psychosocial and spiritual, and has the right to a dignified life that includes the process of death.

It is IAPC's pledge and resolve to facilitate the process and calls upon the Government of India to create and implement suitable and effective legislation and policies for:

Improvement in access to palliative care services and medications

Education of professionals and the public

The enacting of unambiguous laws related to issues in EOLC

Encouragement of participation of the community in care

Monitoring and ensuring standards of care and

Provision of continued supportive measures for the families/caregivers throughout the illness trajectory and even after death.

BACKGROUND

In 2014, the unmet need for palliative care has been mapped in the “Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life”, published jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA). Globally, in 2011, over 29 million people died from diseases requiring palliative care. The estimated number of people in need of palliative care at the end of life was 20.4 million. The biggest proportion, 94%, corresponds to adults of which, 69% are over 60 years of age, and 25% are 15-59-years-old. Only 6% of all people in need of palliative care are children. Based on these estimates, each year in the world, around 377 adults out of 100,000 population over 15-years-old, and 63 children out of 100,000 populations under 15-years-old will require palliative care at the end of life. Globally, great majority of adults in need of palliative care died from cardiovascular diseases (38.5%) and cancer (34%) followed by chronic respiratory diseases (10.3%), HIV/AIDS (5.7%) and diabetes (4.5%). Seventy eight percent of adults and 98% of children in need of palliative care at the end of life belong to low and middle-income countries. According to the 2014 WHO report, India has attained Level 3b integration that is, Generalized Palliative Care Provision with respect to adult palliative care services and with respect to pediatric palliative care provision, India has attained only Level 2 integration which is the Capacity Building Stage.[1]

More than 1 million new cases of cancer occur each year in India with over 80% presenting at stage III and stage IV. Experience from cancer centers from India confirms that two-thirds of patients with cancer are incurable at presentation and need palliative care.[2,3,4] Access to oral morphine is one of the indicators of availability of palliative care services. In India, only 0.4% of the patient population has access to oral morphine.[5] In 2008, India used an amount of morphine that was sufficient to treat pain adequately in only about 40,000 patients suffering from moderate to severe pain due to advanced cancer which is approximately 4% of the population needing the same.[6] Hopefully recent ammendment of the NDPS act will improve access and availability of morphine to these patients.

India has about 100 million elderly at present and this is expected to increase to 324 million by 2050, constituting 20% of the total population. It is estimated that 60% of the elderly patients are affected by cancer.[7] Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) study of the National Cancer Institute in the USA shows that cancer is 11 times more likely to develop in people over 65 years as compared to their younger counterparts.[8] An Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) population-based cancer registry report shows that the prevalence of cancer patients in India above the age of 60 is estimated to reach more than 1 million by 2021.[9]

A report on a study by the Economist Intelligence Unit that was commissioned by Lien Foundation ranked EOLC services in 40 countries (30 OECD countries and 10 select countries), from which data was available. The outcomes of quality of death index showed that India ranked 40 out 40 in EOLC overall score, 37 out of 40 in basic end of life health care environment, 35 out of 40 in availability of EOLC, 39 out of 40 in cost of EOLC, 37 out of 40 in quality of EOLC and scored 2 on a 1-5 scale on public awareness of EOLC where 5 being the highest score.[10] There is an overwhelming need for a national palliative care initiative to bridge these gaps.[11]

A study conducted by Cipla Palliative Care Institute Pune showed that 83% of people in India would prefer to die at home.[12] Palliative care at home is the most cost effective, relevant and practical option in the Indian setting. However, due to lack of awareness among patients and families, and the attitude and lack of knowledge of health care providers about EOLC, significant number of deaths take place in hospitals. Most of the health care expenses are borne by patients and families, and inappropriate and aggressive medical interventions at end of life drain the resources of patients and family.[13] Due to the lack of legal protection, physicians practice defensive medicine, resulting in many inappropriate interventions being done. This ultimately results in holistic suffering instead of holistic care for the dying person and the family. Non-availability of EOLC and rising cost have forced up to 78% of patients to leave hospital against medical advice.[14] The families unilaterally initiate these discharges resulting in these patients not receiving any symptom relief or EOLC measures.

Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine was instrumental in initiating discussions on EOLC in advanced critically ill patients. Initial work, published in 2005, highlighted on limiting life-prolonging interventions and providing palliative care towards the end of life, in Indian intensive care units (ICU).[15] The consensus ethical position statement on guidelines for end of life and palliative care in Indian intensive care was published in 2012.[16]

END OF LIFE CARE

Objectives

Achieve a ‘Good Death’ for any person who is dying, irrespective of the diagnosis, duration of illness and place of death

Emphasis on quality of life and quality of death

Acknowledge that palliative care is a human right, and every individual has a right to a good, peaceful and dignified death.

Principles of a good death

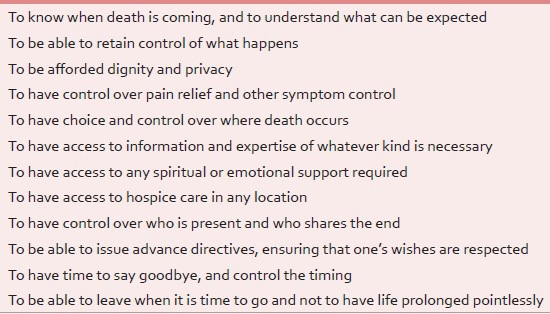

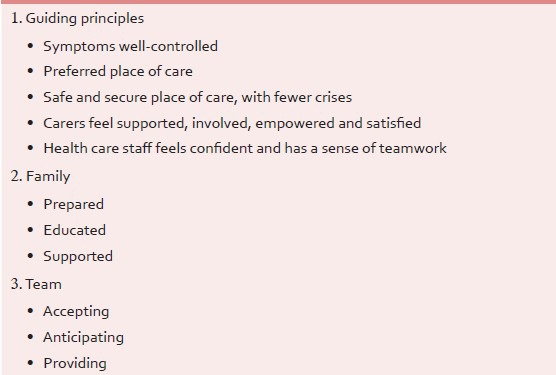

Principles of a good death involve the ability to know when the death is approaching, have physical symptoms well–controlled, patient centered needs met, right to die in a dignified manner at a place of choice and without life needlessly prolonged with artificial means [Table 1].[17]

Table 1.

Principles of a good death

Components of good death

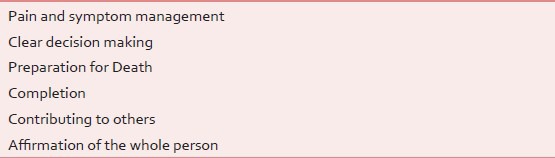

Dying well not only involves adequate control of physical symptoms, but also a host of other things such as unambiguous decision-making on the goals of care, preparation for death and a sense of completion [Table 2].[18]

Table 2.

Components of good death

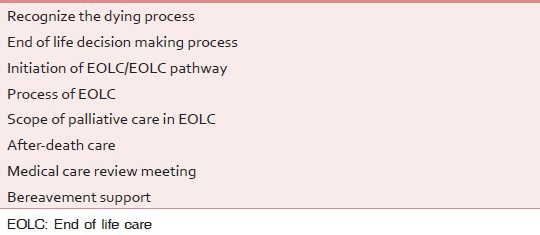

Steps involved in providing good end of life care

The process of providing a good EOLC follows a sequential series of steps which involves recognition, decision making, initiation, providing, bereavement support and review of care process [Table 3].[19]

Table 3.

Steps involved in providing good end of life care

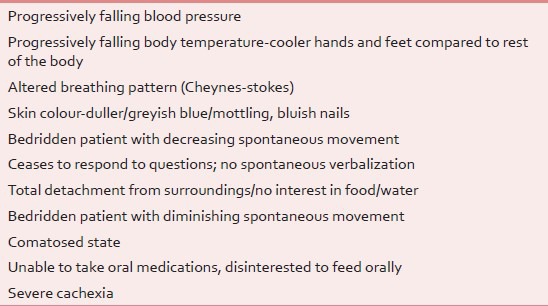

Recognizing the dying process[20]

Recognition of the dying process is the first step in EOLC provision. The process of dying is usually recognized by the change in physiology, such as, failing vital parameters, decreased movement, decreased spontaneous verbalization, decreased intake of food and fluid and skin changes such as greyish mottling and cooling of peripheries, etc. These could be helpful pointers to suggest poor prognosis and very limited life expectancy. However it is not always easy to predict impending death, and the best approach is to treat a possible reversible cause whilst accepting that the patient might be dying [Table 4].[21]

Table 4.

Recognizing that the patient is dying

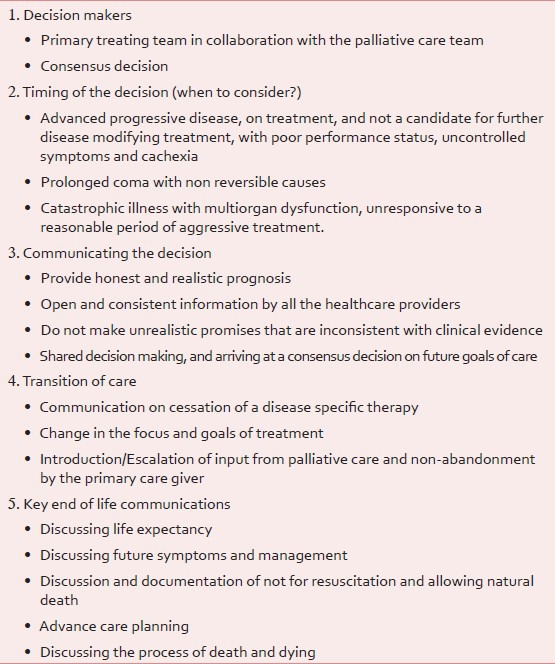

End of life decision making process

End of life decision-making is a complex process but is vital for good EOLC. The decision makers should always be the primary care givers, in consultation with the palliative care team. Primary care givers are the ones who have longer patient/family contact and therapeutic bonding, which could facilitate better communication and decision-making [Table 5].[23]

Table 5.

End of life care decision making process

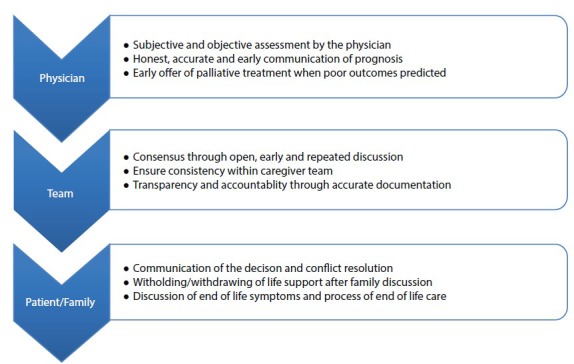

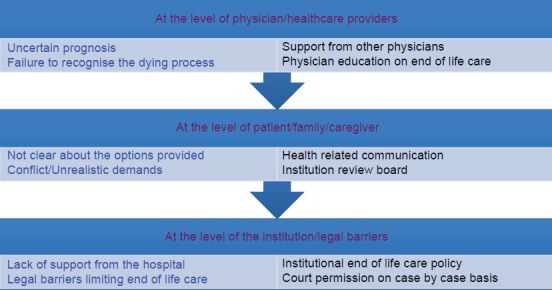

Open honest communication, shared decision-making and smooth transition of the care process are required to facilitate the process. The key EOLC communication should include prognostication, discussion on resuscitation, advance care planning and end of life symptoms [Figure 1]. Despite many studies and data about prognosis and life expectancy, the best estimates still carry a high degree of uncertainty. This is one of the major limitations of the end of life decision-making process [Figure 2].[22] In India, there is an ongoing debate regarding the legality of advanced directives, and the Supreme Court of India has sought opinion from all the States and stakeholders regarding it.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of end of life care

Figure 2.

Complexities in end of life care decision making

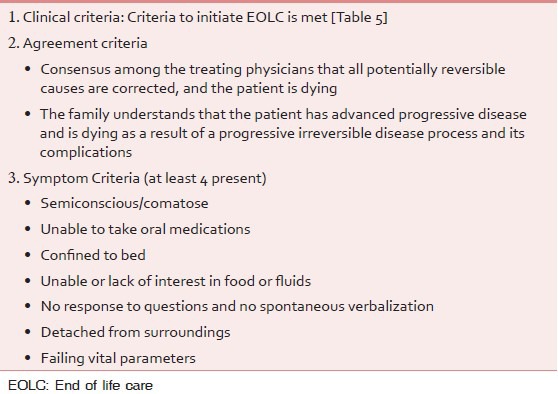

Initiation of end of life care/end of life care pathway

Initiation of the EOLC in dying patients with advanced life limiting illness is guided by three sets of criteria.

Clinical criteria reflect on the advanced nature of illness

Agreement criteria focus on clinician and family consensus and initiation of EOLC

Symptom control criteria focus on end of life symptoms that prompt the clinician to initiate EOLC. Symptom criteria are a helpful pointer to suggest that the patient might be dying. However it is possible that these things are present and yet the patient may not be dying. Hence these criteria must be considered carefully and applied [Table 6].[24]

Table 6.

Initiating end of life care

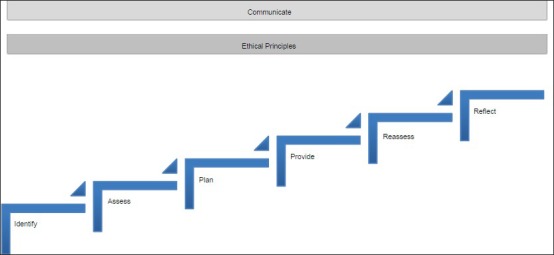

Process of end of life care[25,26,27]

The process of EOLC provision is based on six principles of ‘Gold Standards Frame Work’[28] which include

Identification of patients needing EOLC

Assessment of needs

Planning of EOLC

Provision of the EOLC. Ongoing assessment of the process of EOLC

Reflection on and improvisation of the EOLC process.

The process of EOLC is founded on good communication and ethical principles [Table 7 and Figure 3].

Table 7.

Process of end of life care

Figure 3.

Six step process involved in end of life care

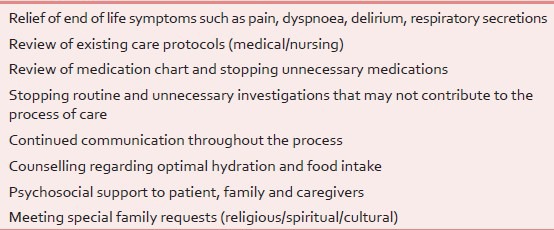

Scope of Palliative care in end of life[29,30]

Palliative care at end of life should include measures to improve pain and symptom control, review and optimization of medication charts, stopping of unnecessary medical interventions and providing psychological, spiritual and social support to patients and families [Table 8].

Table 8.

Scope of palliative care in end of life care

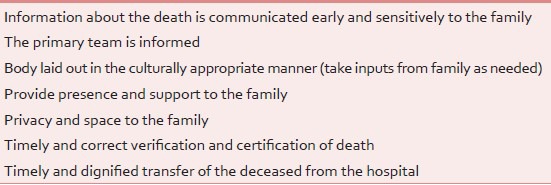

After death care[31]

The care process does not end with the patient's death. After death, the bereaved family should be dealt sensitively, in a culturally appropriate manner and should be provided all logistical support such that the deceased person is transferred out from the hospital in a timely and dignified manner [Table 9].

Table 9.

After death care

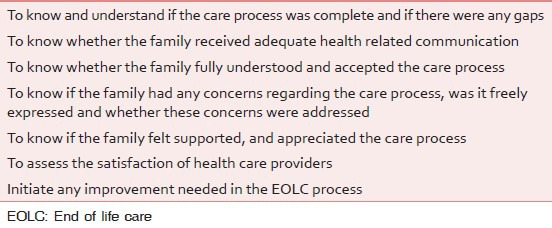

The multidisciplinary team should review the EOLC provided, as a quality initiative, and attempts should be made to bridge gaps in the care process. The review aims to understand the family's perception of the care provided and satisfaction of the healthcare providers such that there is a continued improvement of the EOLC process [Table 10].

Table 10.

Review of care process

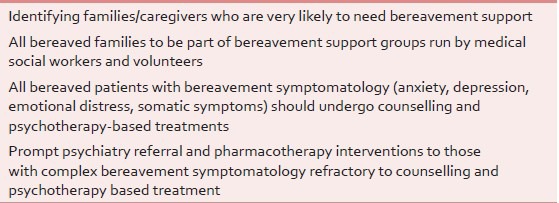

Bereavement care support

Bereavement[32] support should begin with identifying high-risk bereavement individuals/families much before the patient's death. Bereavement symptomatology should be identified and addressed, and referral to a psychologist/psychiatrist should be initiated on a need basis [Table 11].

Table 11.

Bereavement care support

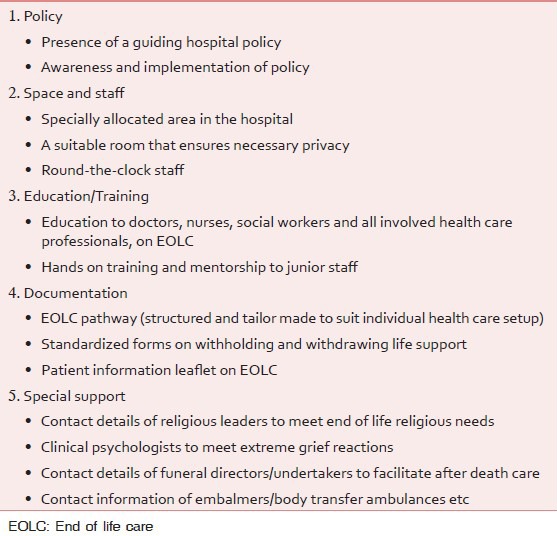

Infrastructural requirements for good end of life care

Presence of EOLC infrastructure[33] is imperative for providing good EOLC. Infrastructural requirements include an overarching policy, presence of dedicated space and trained staff, access to essential medications for end of life symptom management, necessary documentation to facilitate the process, and access to special requirements such as clinical psychologists, religious leaders, funeral directors etc., [Table 12].

Table 12.

Infrastructural requirements for good end of life care

BARRIERS FOR PROVIDING GOOD END OF LIFE CARE IN INDIA

Studies show that physicians in India are reluctant to consider limitation of life support interventions when compared to their western peers. This is primarily due to the lack of a clear legal framework on this issue, rather than prevalent social and cultural customs.[34,35,36,37]

A study conducted in Mumbai among ICUs of public and private hospitals shows that limitation of life sustaining treatment was much greater in cancer and public health care institutions when compared to the private health care system.[38] An audit on EOLC practices in a public tertiary Indian cancer hospital showed that at least 39% of patients with advanced metastatic cancer having refractory acute illness staying for >1 day in ICU, receive some form of limitation of life sustaining treatment. In the same setting, withholding of life sustaining treatment was carried out in 73% and withdrawing of life sustaining treatment in 27%of patients.[39] Disparity between EOLC practices between public and private health care is quite glaring, and this disparity is partially due to the lack of a clear legal framework, and possible economic incentives offered to the staff by some hospitals.

The culture of medical practice in India is generally ‘paternalistic’ with little consideration for the patient's autonomy and the respect for the patient's choices. Medical education in India is founded strongly on the ‘acute model of care’, which is assessment and treatment leading to cure. The medical system has not kept pace with the changing pattern of illness and their trajectory. Hence, lack of knowledge of ‘chronic care and palliative care’ has led to treating end of life patients acutely and inappropriately. This, compunded by the lack of a national policy and legal backing, has led to defensive practice of medicine and physicians practicing in the fear of being accused of providing sub-optimal, care or of possible criminal liability of limiting therapies.

Continued unrealistic hope, and the constant search for cure by the patients and families are important barriers for EOLC provision. The prevalent quackery and alternative medicine practitioners making unrealistic promises of cure, often lure the patients and families towards considering incongruous selections. Sometimes these treatment processes are very laborious and painful, depriving these patients, essential and comforting EOLC.

LEGAL PITFALLS IN PROVIDING END OF LIFE CARE

There are no legal framework or policies guiding the clinicians on EOLC or dignified death.[40,41] After hearing the public interest litigation on the Aruna Shanbaug case, the Supreme Court of India ruled, “Involuntary passive euthanasia was allowed in principle” but must follow a strict procedure involving clearance by a High Court.

Involuntary passive euthanasia is obsolete medical terminology, which is no longer used.[41] The principles guiding good EOLC involve respecting patient choices, consideration of futility, deliberated consensus decision-making, and moreover, a humane touch. Any comparison drawn between EOLC and involuntary passive euthanasia is foolhardy. The legal standpoint on EOLC remains a dilemma as the highest court in the country has addressed only the issue of euthanasia and is silent about EOLC.

ETHICS OF END OF LIFE CARE

Patient autonomy, or respecting the patient's choices, is the cornerstone of end of life decision-making. The patient has the right to consent or refuse, and in the event the patient has diminished decision making capacity, surrogates acting on the patient's behalf can communicate the patient's previously expressed wishes.[43,44]

Beneficence is to do what is in the best interest of the patient. In the context of an advanced progressive illness with no scope for reversal, the best interests of the patient are controlling the patient's pain and symptoms, and reducing the sufferings of the patient and his family, providing emotional support and protecting the family from financial ruin.[42]

Therefore, withholding and withdrawing of the life support, in this context, is a humane approach of ‘allowing natural death,’ that is, allowing the patient to die of the underlying illness, with symptoms well–controlled, in a dignified manner, in the presence of his family and loved ones and this in no way amounts to euthanasia.

Euthanasia is a voluntary act where an intervention is performed to hasten the dying process.[45] Non-malfeasance in this context is not instituting or escalating aggressive medical interventions in a futile condition. Futility as defined by the American Thoracic Society is “A life-sustaining intervention is futile if reasoning and experience indicate that the intervention would be highly unlikely to result in a meaningful survival for that patient”.[46] Hence, instituting a futile intervention after fully understanding the irreversible nature of illness, amounts to harm and assault. Understanding the futility will prompt the medical practitioners to initiate discussions on EOLC.[47] Distributive justice will enable the medical practitioners to allocate optimally, the medical, technical, human and financial resources.[48]

The ethical basis of EOLC can be best explained by four principles of the doctrine of double effect.

The act itself must be morally permissible. Good EOLC is providing the most appropriate and humane care at the terminal phase of life in a patient with advanced irreversible illness where the physical, emotional and psychological issues are dealt with, and families and caregivers are supported through this transition. This amounts to the highest degree of care and is morally and ethically permissible

The ill effect, while foreseen, must be unintended. EOLC is strongly founded on principles of palliative care, where it affirms life and does not hasten the dying process nor needlessly prolongs the dying by artificial means in a futile situation. All the medications and interventions carried out in this context are to relieve symptoms and maximise comfort. Hence, if there is an inadvertent shortening of life, it is unintentional

The ill effect must not be disproportionate to the good effect. During EOLC symptom management, all medications are carefully titrated and used. In palliative sedation the doses of sedatives are titrated such that the minimum possible dose is used to alleviate the symptom distress

The ill effect is not the means by which the good effect is achieved. The core principle and intent of palliation in EOLC is ‘killing the symptom and not the patient’. Hastening death is not a means to attain symptom relief in EOLC. By careful and persistent attention to details, one can ensure that all patient directed interventions are based on clinical evidence, ethical and moral principles, and humane touch.[49]

However, the current evidence suggests that the doctrine of double effect may come in the way of good EOLC as justification needs to provided about ill effects, and good death is not an ill effect but a desired effect.[50]

Formulating the position paper

Initial conceptualisation of the position paper on EOLC policy as applied to India, was initiated in Feb 2013 at the IAPC Conference at Bangalore, which gained momentum over a year, and a steering committee for the same was appointed in Feb 2014 at the IAPC Conference at Bhubaneswar. The steering committee comprised a group of palliative care experts working in public health care, private health care and hospice care.

A joint meeting between Indian Critical Care Society and IAPC was held in May 2014. The outcome of the meeting was that the IAPC would formulate a position paper on EOLC policy, and this position paper will be made available on the website and circulated among the stake holders. Once consensus is achieved, the paper will be published in the Indian Journal of Palliative Care, the official journal of IAPC. Subsequently Indian Association of Palliative Care and Indian Critical Care Society will formulate jointly the EOLC policy document and procedural guidelines.

RECOMMENDATIONS OF INDIAN ASSOCIATION OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Recommendation 1: Advocacy for end of life care

Access to receive good palliative and EOLC is a human right

All patients are entitled to a dignified death.

Access to palliative care is recognized under International Human Rights law. According to a UN special report on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, denial of pain treatment, failure to ensure access to pain and symptom control measures, failure to prevent unnecessary suffering from pain, amount to cruel and degrading treatment.[51]

The sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted the following resolution: Irrespective of whether the disease or condition can be cured, good end-of-life care for individuals is among the critical components of palliative care.[52]

The IAPC has taken several steps to advocate this cause, which includes developing a national palliative care plan, assisting the Government of India (GOI) in implementing in its five year plan (vide: “Proposal of Strategies for Palliative Care in India”) and creating a nationwide consortium of palliative care organizations for implementation of this strategy. The recent success for the palliative care community in India is the passing of amendments to the NDPS Act by both the houses of the Indian Parliament.

IAPC advocates strongly, access to good palliative care and dignified death as a human right, and envisages its attainment through improved awareness, education, creation of infrastructure and a supportive policy and legislation.

Recommendation 2: End of life care policy

GOI to take urgent steps towards a legislation supporting good EOLC

All hospitals and medical institutions to have a functional EOLC policy.

IAPC requests the Law Commission of India to expedite changes in the law to facilitate the process of achieving a good death. The IAPC continues to view with concern, the inordinate delay in the matter of enacting the ‘Medical treatment to terminally ill patients (Protection of patients and medical practitioners) Bill, 2006’ based on the 196th report of the Law Commission of India, and calls upon the Ministry of Health, GOI to take urgent steps to ensure that the law is passed without delay.

IAPC recommends all the hospitals dealing with patients with advanced life limiting illness to have an overarching standard EOLC policy that supports the healthcare professionals to provide appropriate EOLC for the patients who are dying of a terminal illness. The policy also should pave the way for providing access to EOL medications, creating end of life infrastructure and education and necessary standard forms (documents) needed for EOLC provision.

Recommendation 3: Process of end of life care

Providing a comprehensive care process that minimizes end of life symptoms, manages psychosocial, emotional, spiritual and existential distress of patients and families and facilitates a dignified pain free death

Access to essential medications and infrastructure for providing EOLC.

The process of EOLC should include recognition of the dying process, honest and sensitive communication with the patient (if possible) and the family, stopping unnecessary medical and nursing interventions, review of medications and ensuring the stopping of unnecessary medications and anticipatory prescription of essential medications. This will ensure prompt and good control of end of life symptoms. Process of EOLC also includes review of hydration and nutritional status and family counselling regarding the same, discussing the care process and institution of EOLC pathway as appropriate, regular assessment and reassessment during the care process and any variances promptly dealt with, supporting the patient during the dying process and providing culturally appropriate after death care, verification and certification of death as early as possible and a smooth and dignified transfer of the body out of the hospital, and supporting the family during the bereavement period.

Families of patients choosing to be cared for at home must be empowered with knowledge, skills, and support by a palliative home care team.

The care process should also include access to parenteral (subcutaneous) medications at home and families should be educated about administering these medications. In the event of out of hospital death, the local general practitioner should be encouraged to verify the death and provide the verification letter. The death certificate could be provided later by the hospital.

Recommendation 4: Implementation of end of life care policy

Palliative care and EOLC to be part of all hospital-based care

Palliative care and EOLC to be part of all community/home-based program.

IAPC desires that palliative care and EOLC should be considered as an essential medical service in all hospitals that cater to EOLC. The patients and families/caregivers should be made aware of this service and the hospital should employ trained health professionals for delivering this service. All community and home based medical and nursing services should include palliative and EOLC service as one of their healthcare delivery packages.

Recommendation 5: End of life care standards

The standards of palliative care and EOLC as established by the appropriate authorities must be followed and attained as much as possible

Standards of EOLC provision accredited and monitored by National Accreditation Boards.

IAPC recommends the creation of suitable training programmes in palliative care and will work with appropriate educational bodies to ensure their accessibility.

IAPC wishes that all those institutions providing EOLC meet these standards as far as possible. NABH and JCI as a part of their accreditation process require hospitals to have a working EOLC policy. However, most often, these policies are confined to paper.

The IAPC urges the International and National Accreditation Boards such as National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers (NABH), Joint Commission International (JCI) and Medical Council of India (MCI) to mandate a standard and uniform Palliative and EOLC Policy for the Dying as outlined above, in all healthcare institutions, and monitor its compliance through periodic audit.

Recommendation 6: End of life care education

All doctors and nurses involved in direct patient care to undergo mandatory EOLC training and certification

EOLC training to be part of undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum for medical, nursing and allied health streams.

All the health care providers involved in direct patient care should undergo a mandatory 4 hours of basic essential training in EOLC provision. All hospitals caring for patients with advanced life limiting illness should make this certification mandatory as a part of workplace requirement.

IAPC desires that the medical, nursing and allied health undergraduate and postgraduate curricula have dedicated teaching and training time in palliative and EOLC. IAPC stresses the need for education and empowerment of families and caregivers in EOLC education.

CONCLUSION

IAPC will make continued efforts to improve the EOLC provided to patients and families/caregivers.

This position paper is an effort to achieve this goal by developing a nationwide uniform EOLC policy, creating an appropriate environment for its provision and encouraging the participation of all the stake holders such that a common goal is attained. The position paper is envisaged to support and facilitate those health care providers who aim to make a difference in lives of the patients who are dying.

IAPC hopes that a nationwide EOLC policy would pave the way for clinical excellence in care for the dying, facilitates standard and scientific care processes, research and development and, above all, provide the human touch to patients in the very crucial phase of theirs life's journey.

FUTURE

IAPC proposes to create guidelines, algorithms, manuals, toolkits, standard forms to ensure quality care is provided for all at end of life.

EOLC user manual and tool kit

Standard EOLC pathway appropriate to Indian socio-cultural context

Algorithms for management of end of life symptoms

EOLC training module

Framework for application of standard format of ethics in EOLC

Framework for surrogate decision-making in EOLC

Framework for documentation of EOLC

Standard formats for documenting not for resuscitation, allowing natural death and withholding/withdrawing inappropriate life sustaining treatment

Standard format for EOLC Informed Consent

Current legal/Indian Penal Code provisions protecting the practitioner adopting/practicing EOLC

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for both health care provider and patient/caregiver.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Connor S, Bermedo MC. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. World Palliative Care Alliance. World Health Organization. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Country Report India. Report of International Observatory of End of Life Care. Lancaster University. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Report of International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nandakumar A, Gupta PC, Gangadharan P, Visweswara RN. Development of Cancer Atlas in India. Report of National Cancer Registry Program, ICMR. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharathi B. Oral morphine prescribing practices in severe cancer pain. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:127–31. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.58458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unbearable Pain: India's Obligation to Ensure Palliative Care. Report of Human Rights Watch. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations: Report of Population Division, DESA; World Population Ageing 1950-2050. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ries LA, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller MA, Clegg L, et al. Report of surveillance, epidemiology and end result (SEER) program cancer statistics review 1975-2006. National Cancer Institute Bethsedha [Google Scholar]

- 9.ICMR Population based cancer registry program-2 year report 2004-05. Report of National Cancer Registry Program, ICMR [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray S, Line D, Morris A. The quality of death ranking end of life care across the world. Report of Economic Intelligence Unit, Lien Foundation. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macaden SC. Moving toward a national policy on palliative and end of life care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17(Suppl):S42–4. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.76242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni P, Kulkarni P, Anavkar V, Ghooi R. Preference of the place of death among Indian people. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:6–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayaram R, Ramakrishnan N. Cost of intensive care in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:55–61. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.42558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani RK. Limitation of life support in the ICU. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2003;7:112–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mani RK, Amin P, Chawla R, Divatia JV, Kapadia F, Khilnani P. Limiting life-prolonging interventions and providing palliative care towards the end of life in Indian intensive care units. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2005;9:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mani RK, Amin P, Chawla R, Divatia J, Kapadia F, Khilnani P, et al. Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units’ ISCCM consensus ethical position statement. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:166–81. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.102112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith R. Principles of a good death. Br Med J. 2000;320:129–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: Observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman L, Ellershaw J. Care in the last hours and days of life. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;39:674–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy C, Brooks-Young P, Brunton Gray C, Larkin P, Connolly M, Wilde-Larsson B, et al. Diagnosing dying: An integrative literature review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: The last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326:30–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/Caregiver Preferences for the Content, Style, and Timing of Information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quality standard for end of life care for adults. NICE Quality Standards. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS13 .

- 24.Phillips JL, Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM. End-of-life care pathways in acute and hospice care: An integrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:940–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan R, Webster J. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD008006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008006.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawkins N, Bawn R. The gold standards framework competency document. End Life Care. 2010;4:58–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gold Standards Framework for End of Life Care. [Last accessedon 2012 Sep]. Available from: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk .

- 28.London: Department of Health Publication; 2008. End of Life Care Strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantilat SZ, Isaac M. End-of-Life care for the hospitalized patient. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:349–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olausson J, Ferrell BR. Care of the body after death. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:647–51. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.647-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temkin-Greener H, Zheng NT, Norton SA, Quill T, Ladwig S, Veazie P. Measuring end-of-life care processes in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2009;49:803–15. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forte AL, Hill M, Pazder R, Feudtner C. Bereavement care interventions: A systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2004;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherny NI, Catane R, Kosmidis P. ESMO Taskforce on Supportive and Palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1335–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnett VT, Aurora VK. Physicians beliefs and practice regarding end-of-life care in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:109–15. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.43679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mani RK, Mandal AK, Bal S, Javeri Y, Kumar R, Nama DK, et al. End-of-life decisions in an Indian intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1713–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salins NS, Pai SG, Vidyasagar M, Sobhana M. Ethics and medico legal aspects of “not for resuscitation”. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:66–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.68404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapadia F, Singh M, Divatia J, Vaidyanathan P, Udwadia FE, Raisinghaney SJ, et al. Limitation and withdrawal of intensive therapy at the end of life: Practices in intensive care units in Mumbai, India. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1272–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165557.02879.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myatra SN, Divatia J, Tandekar A, Khanvalkar V. An audit of end of life practices in an indian cancer hospital icu. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:S386. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balakrishna S, Mani RK. Constitutional and legal provisions in Indian law for limiting life support. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2005;9:108–14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Supreme Court of India Proceedings. Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug vs The Union of India and Ors. Writ Petition (Criminal) No 115 of 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michalsen A, Reinhart K. “Euthanasia”: A confusing term, abused under the Nazi regime and misused in present end-of-life debate. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1304–10. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beauchamp T. The Principle of Beneficence in Applied Ethics. In: Edward NZ, editor. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandman L, Munthe C. Shared decision-making and patient autonomy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2009;30:289–310. doi: 10.1007/s11017-009-9114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tilden VP. Ethics perspectives on end-of-life care. Nurs Outlook. 1999;47:162–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(99)90091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 2010;376:1347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Thoracic Society. Withholding and withdrawing lifesustaining therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:478–85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baily MA. Futility, autonomy, and cost in end-of-life care. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39:172–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buchanan DR. Autonomy, paternalism, and justice: Ethical priorities in public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:15–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyle J. Medical ethics and double effect: The case of terminal sedation. Theor Med Bioeth. 2004;25:51–60. doi: 10.1023/b:meta.0000025096.25317.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sykes N, Thorns A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:312–8. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendez JE. United Nations; 2013. Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Human Rights Council. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care. World Health Assembly Report. World Health Organization. 2014 [Google Scholar]