Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause serious infections in humans. Autophagy-related gene 7 (Atg7) has been implicated in certain bacterial infections; however, the role of Atg7 in macrophage-mediated immunity against Kp infection has not been elucidated. Here we showed that Atg7 expression was significantly increased in murine alveolar macrophages (MH-S) upon Kp infection, indicating that Atg7 participated in host defense. Knocking down Atg7 with small-interfering RNA increased bacterial burdens in MH-S cells. Using cell biology assays and whole animal imaging analysis, we found that compared with wild-type mice atg7 knockout (KO) mice exhibited increased susceptibility to Kp infection, with decreased survival rates, decreased bacterial clearance, and intensified lung injury. Moreover, Kp infection induced excessive proinflammatory cytokines and superoxide in the lung of atg7 KO mice. Similarly, silencing Atg7 in MH-S cells markedly increased expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Collectively, these findings reveal that Atg7 offers critical resistance to Kp infection by modulating both systemic and local production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: autophagy, alveolar macrophage, Gram-negative bacterial infection, lung injury, knockout mice, reactive oxygen species, autophagy-related gene 7

bacterial pneumonia is a major cause of mortality in the United States and worldwide (33). Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) is a Gram-negative bacterium and is the third most common organism isolated from intensive care units in the United States (20). Despite intense research in understanding the pathogenesis and host-pathogen interaction, the mechanisms by which Kp is cleared from the lung by alveolar macrophages (AM) are largely undemonstrated, thereby impeding the development of novel strategies for control of this infection.

Autophagy, through a lysosomal degradation mechanism, is essential for cell survival, differentiation, development, and homeostasis. Impaired autophagy may be involved in several diseases, including cancer and inflammatory diseases (28, 29). Autophagy-related gene 7 (Atg7), a critical E1-like ubiquitin, has been involved in multiple physiological and pathological conditions (24, 25) as well as in viral and bacterial infection (16, 27, 41). However, whether Atg7 participates in host defense against Kp infection has not been elucidated. Previously, our laboratory has shown that Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection could induce autophagy in AM (51). In this paper, we sought to elucidate the mechanisms of autophagy in Kp infection.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), widely recognized as a master transcription factor, plays a major role in a variety of inflammatory disorders. NF-κB, a critical transcription factor in a variety of cellular processes (4, 40), appears to be involved in autophagic negative regulation of inflammatory responses. The degradation of IκB kinase may be modulated by an autophagy pathway (40). Furthermore, the liver of beclin-1 mutant mice exhibits increased apoptosis and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production as well as NF-κB activation due to the accumulation of p62 (31). These findings suggest that autophagy may negatively impact inflammatory responses by influencing NF-κB signaling pathways. The dissociation of NF-κB from IκBα promotes the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, thereby activating a number of downstream cytokine genes, such as TNF-α and IL-6 (4, 40).

Here, we employed a Kp infection mouse model to investigate the function of Atg7 in host defense. Our data demonstrated that atg7 deficiency in mice led to a severe infectious phenotype due to a dysregulated cytokine production. Hence we set out to investigate the cellular regulatory process and underlying molecular mechanism involved in the intensified proinflammatory response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal handling.

atg7 knockout (KO) mice (in a C57BL/6J background) were kindly provided by Dr. Youwen He (Duke University) (19). Atg7 flox/flox (Atg7f/f) mice were generated as reported (24). Mouse atg7 gene has 17 exons that span 216-kb long genomic DNA. Exon 14 encoded the active site cysteine residue. Cre-loxP technology was used to conditionally disrupt the exon 14 by breeding Atg7f/f mice with ER-cre mice (44). Atg7 deficiency was induced by intraperitoneally injecting tamoxifen 0.1 mg/kg three times. Mice were kept and bred in the animal facility at the University of North Dakota, and the animal experiments were performed under National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Mice were given 45 mg/kg ketamine and intranasally infected with 5 × 105 CFU/mouse (6 mice/group). The mice were killed when they became moribund to obtain survival curves (50), whereas additional mice were used to attain data at designated times. After bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), the trachea and lung were obtained for cell biology assays or fixed in 10% formalin for histological analysis.

Cell culture.

Mouse AM cells were isolated by BAL as described (50). AM cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% newborn calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics in a 5% CO2 incubator. Murine alveolar epithelial cell line (MLE-12) and murine AM cell line (MH-S) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). These cells were maintained in F-12-DMEM medium (1:1) and RPMI 1640 medium with 5% newborn calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics, respectively.

Bacterial strains and infection.

The Kp strain (ATCC 43816 serotype II strain) was provided by Dr. V. Miller (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) (26).

Bacteria were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Optical density (OD) was measured at 600 nm, 0.1 OD = 1 × 108 cells/ml. Cells were infected by Kp with a 10:1 (bacteria-cell) ratio (50).

Cell transfection.

Cells were transfected with Atg7 small-interfering RNA (siRNA; Invitrogen) using LipofectAmine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium following the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were lysed after 24 h of transient transfection to evaluate the expression (50).

Tandem GFP-RFP-LC3 plasmids were transfected to MH-S cells for 24 h as reported previously (51). The tandem RFP-GFP-LC3 plasmid was generated and kindly provided by Tamotsu Yoshimori of Osaka University, Japan (23). The RFP-GFP-LC3B plasmids allow enhanced dissection of the maturation of the autophagosome to the autolysosome. By combining an acid-sensitive GFP with an acid-insensitive RFP (TagRFP), the change from autophagosome (neutral pH) to autolysosome (acidic pH) can be microscopically determined by loss of GFP fluorescence but not red fluorescence, indicating that RFP-LC3 can label the autophagic compartments both before and after fusion with lysosomes. After Kp infection, the cells were observed by confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Inflammatory cytokine profiling.

After infection, BAL fluid was collected to measure the cytokine concentrations using an ELISA kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The trachea was surgically exposed, and lungs were lavaged five times with 1.0 ml volume of lavage fluid to obtain BAL fluid. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation. For ELISA assay, 96-well plates (Corning Costar 9018) were first coated with 100 μl/well capturing antibodies in coating buffer overnight at 4°C (50). Aliquots (100 μl) of samples were added to the coated wells. After incubation with corresponding detection-HRP-conjugated antibodies, the plate was read at 450 nm and analyzed to determine the cytokine concentrations using the known cytokine standards.

Western blotting assay.

Cells or lung homogenates were collected and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.35% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assays (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of individual protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then electrotransferred onto the nitrocellulose membrane (10). Membranes were blocked for 30 min with 5% skim milk in TBST buffer composed of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies against Atg7 were purchased from Invitrogen; antibodies against IL-6, NF-κB, phospho (p)-NF-κB (ser536, sc-33020), GAPDH, p38, p-p38 (D-8, SC-7973), IL-1β, and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; GAPDH or β-actin was used as loading control. After incubation with secondary antibodies, ECL detection reagents (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to detect signals (13, 14, 36).

Confocal microscopy and indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Cells were grown in 3-cm glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA). After infection, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. After incubation with the blocking buffer for 30 min, primary Abs were added at a 1:500 dilution in blocking buffer and continued incubation overnight. The next day, cells were washed three times with washing buffer (5, 48). After incubation with appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary Abs, the cells were kept in mounting medium before taking images (22). The images were taken by an LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY).

Nitroblue tetrazolium assay.

This assay is used to detect the released superoxide. The color of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) dye changes upon reduction by released superoxide. The dye is yellow in color and after reduction by superoxide forms a blue formazan product. After 24 h infection with Kp, the dye was added as reported (50).

Dihydrodichlorofluorescein diacetate assay.

Dihydrodichlorofluorescein diacetate dye (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) only emits green fluorescence upon reaction with superoxide inside cells. Cells were seeded in the 96-well plates and treated as above. After 10 min incubation with the dye, fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) (12, 46).

Lipid peroxidation assay.

After infection, lungs were homogenized and lysed in 62.5 mM Tris·HCl (pH = 6.8) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Thermo). Malondialdehyde could be measured in a colorimetric assay (Calbiochem) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Next, the protein concentration is measured and adjusted to a uniform level for the assay (45).

Phagocytosis assay.

MH-S cells were plated in 24-well plates and grown overnight. The cells were treated with the antibiotic-free medium immediately followed by Kp infection. After 1 h incubation at 37°C, the wells were washed and treated with 100 μg/ml polymyxin B for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria (21, 50). After being washed with PBS three times, the cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100. Then colony-forming units (CFU) were counted to quantify phagocytosis.

Myeloperoxidase assay.

Lung tissue samples were homogenized in 50 mM hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.0, 0.5 mM EDTA at 1 ml/100 mg of tissue and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. Precipitate was collected and 100 ml of reaction buffer (0.167 mg/ml O-dianisidine, 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.0, and 0.0005% mM H2O2) were added to 100 ml of the sample. Absorbance was read at 460 nm at 2-min intervals. Triplicates were used for each sample and control (21, 50).

Bacterial Burden Assay.

AM cells from BAL fluid and lungs were homogenized in PBS and spread on LB plates to determine the number of bacteria (50).

Histopathology analysis.

Lung tissues were fixed in 10% formalin using a routine histologic procedure. The fixed tissue samples were processed for obtaining standard hematoxylin and eosin staining and examined for differences in morphology postinfection (47).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated at least three times. Data were presented as percentage changes compared with controls ± SD from the three independent experiments. A difference was accepted at P < 0.05 (Student's t-test) by use of Prism software (46). The survival test results were represented by Kaplan-Meier survival curves using prism software.

RESULTS

Atg7 was involved in Kp clearance in MH-S cells.

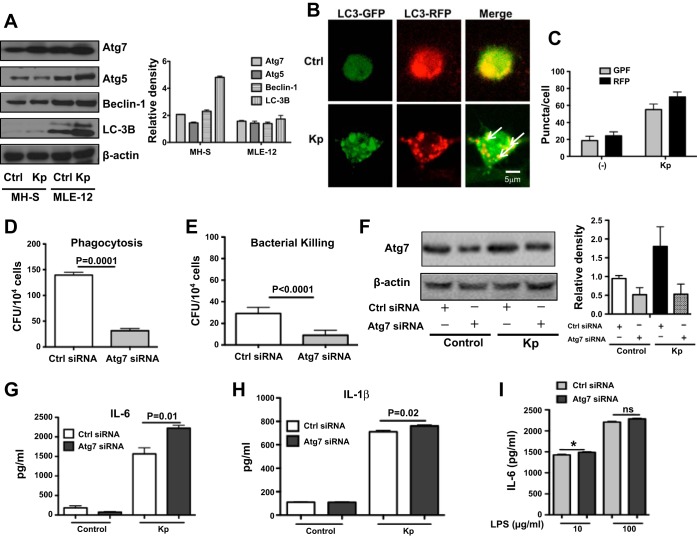

MH-S and MLE-12 cells are widely used as models for studying molecular characteristics of murine lung macrophage and epithelial cells, respectively (9, 32). We first screened several autophagy-related proteins, including beclin-1, Atg5, and Atg7, and found that expression of Atg7 was significantly increased after Kp infection, especially in MH-S cells (about 2-fold) compared with uninfected controls (Fig. 1A). Thus, we chose MH-S cells for the following experiments. We further observed that LC-3 was converted from LC3-I to LC3-II after Kp infection, suggesting that autophagy is induced by infection (Fig. 1A). To verify the induction of autophagy by Kp, we transfected a tandem RFP-GFP-LC3 plasmid into MH-S cells. RFP-GFP-LC3 plasmid was designed to differentiate the autophagosome and autolysosome. The tandem RFP-GFP-LC3 construct can form puncta, suggesting autophagosome formation. Once an autophagosome fuses with a lysosome, the GFP moiety degrades while RFP-LC3 maintains the puncta and fusing with autolysosomes. After tandem construct transfection and followed with Kp infection, we demonstrated an increase of LC3 punctation in both green and red fluorescence (Fig. 1, B and C). However, there were markedly increased RFP puncta in infected cells than those in control cells, confirming the induction of autolysosome formation. Taken together, these findings establish that Kp infection can specifically induce autophagy in MH-S cells, since the tandem plasmid can exclude the possibility of lysosome deficiency-induced LC-3 accumulation (51). These findings prompted us to determine the role of Atg7 in bacterial clearance. Bacterial Burden Assay demonstrated that a downregulated Atg7 by siRNA silencing led to decreased bacterial phagocytosis and clearance compared with the scrambled siRNA controls (Fig. 1, D and E). Successful knockdown of Atg7 was confirmed by measuring protein expression using Western blot analysis (Fig. 1F). To examine the effect of autophagy on inflammation, we measured cytokine levels after Atg7 siRNA silencing and found that suppressing Atg7 increased cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-6 and IL-1β) in MH-S cells compared with uninfected and scrambled siRNA controls using ELISA (Fig. 1, G and H). Although IL-1β was also increased, the change of IL-6 was more substantive, suggesting an IL-6 dominant inflammatory response. To assess which component of Kp is a major immune stimulator, we also compared the potency of whole organism and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in inducing cytokine secretion in MH-S cells. We showed that both LPS and live Kp increased cytokine production, but live Kp induced higher IL-6 levels in Atg7 siRNA groups than scrambled siRNA groups (Fig. 1, G and I). These results suggest that the whole pathogen is required for inducing inflammatory responses despite the involvement of LPS (6).

Fig. 1.

Autophagy-related gene 7 (Atg7) was involved in bacterial clearance and inflammatory responses in MH-S cells. A: increased expression levels of Atg7 in MH-S and MLE-12 cells 2 h post Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) infection as assessed by Western blot analysis. Gel data were quantified using densitometry with ImageJ software. The expression levels of the proteins were quantified relative to β-actin. B: tandem GFP-RFP-LC3 plasmids were transfected to MH-S cells for 24 h. Next, the cells were infected with Kp for 1 h [multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 10:1]. Arrows indicate LC3 puncta. C: puncta numbers (>10 in each cell) were considered as positive cells (at least 100 cells/group). D and E: knocking known Atg7 with small-interfering RNA (siRNA) in MH-S cells decreased bacterial phagocytosis and clearance after Kp infection, respectively, using colony-forming unit (CFU) assay with polymyxin B treatment (see materials and methods). F: Atg7 was knocked down with siRNA and followed by Kp infection detected by Western blot. G and H: increased cytokine secretion in MH-S cells by knocking down Atg7 with siRNA silencing and Kp infection (ELISA). Data were representative of three experiments with similar results. I: IL-6 secretion in Atg7 siRNA silencing MH-S cells after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge. LPS was derived from Kp. Cells were treated with different doses of LPS (10 and 100 μg/ml) for 2 h, and then the medium was collected to detect cytokine secretion by ELISA (Student's t-test, *P < 0.05).

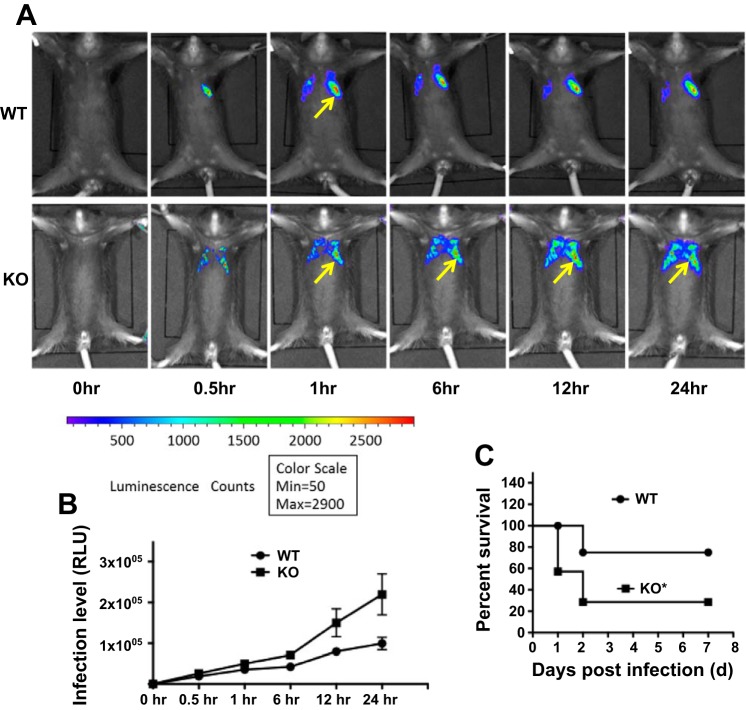

atg7 KO mice exhibited decreased survival rates upon Kp infection.

To investigate the physiological relevance of Atg7 in Kp infection, we employed atg7 KO mice to examine outcomes following bacterial invasion. After intranasally instilling luminescence emitting Kp (5 × 105 CFU/mouse), we noted increased bacterial retention and dispersion in the lung of atg7 KO mice compared with that of wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 2, A and B) by a small animal imaging system (IVIS XRII; Caliper). The powerful in vivo imaging enabled the determination of accumulated bacteria in a spatiotemporal manner without killing animals. We found that atg7 KO mice exhibited quicker spread, wider distribution (both left and right lung lobes vs. only left lung lobes), and longer persistence than those in WT mice, confirming the critical role of Atg7 in host defense against Kp infection. In addition, atg7 KO mice exhibited increased lethality (40% atg7 KO mice died within 24 h postinfection) as shown in Fig. 2C. At 48 h, 80% of KO mice died, whereas 80% of WT control mice remained alive (n = 6). This result is analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves (P < 0.05, log rank test). Taken together, these findings indicate that Atg7 is critically required for host defense against Kp infection in acute pneumonia models.

Fig. 2.

atg7 knockout (KO) mice displayed an increased susceptibility to Kp infection. A: in vivo imaging (whole body) of Kp infection in mice. atg7 KO mice and wild-type (WT) mice were intranasally challenged with 5 × 105 CFU/mouse. Images showing bioluminescence of different time points using IVIS XRII small animal imaging machine (Caliper) (arrows indicating Kp spread region). Imaging shown is representative of 6 mice for each group. B: quantification of Kp infection process represented by the bacterial luminescence intensity over time of A. Data are presented as means ± SE. C: survival of atg7 KO and WT mice was represented by Kaplan-Meier survival curves (n = 6, P = 0.0195; 95% confidence interval, log rank test).

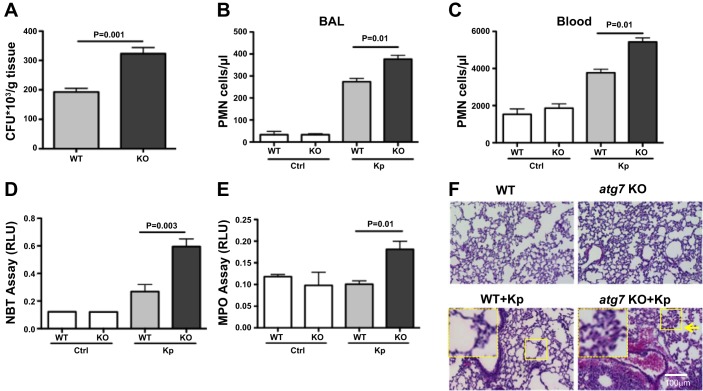

atg7 KO mice showed increased bacterial burdens and oxidation.

atg7 KO mice showed significantly increased CFU of Kp in the lung tissue (P = 0.001, Fig. 3A) compared with WT mice, indicating more severe pneumonia occurring in atg7 KO mice. We found increased polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration in both BAL fluid and serum of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 3, B and C).

Fig. 3.

Increased bacterial burdens, polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) penetration, and oxidative injury in the lungs of atg7 KO mice following Kp infection. A: atg7 KO mouse lungs showed significantly increased bacterial burdens after infection with Kp compared with those of WT mice. atg7 KO mice and WT mice were infected with 5 × 105 CFU Kp/mouse. Tissues were homogenized in PBS (n = 6). The same amounts of tissue were evaluated for bacterial colonies for CFU/g of tissue. B and C: increased PMN infiltration was observed in the lung and serum of atg7 KO mice compared with that of WT mice. After HEMA-3 staining, PMN cell percentages were calculated vs. total nuclear cells. D: superoxide production of alveolar macrophage (AM) cells was significantly increased in atg7 KO mice compared with WT mice using a nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) assay (1 μg/ml). AM cells were seeded in 96-well plates and infected with Kp at MOI of 10:1 for 1 h. The optical density for NBT was determined at 560 nm. E: increased myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in atg7 KO mouse lungs compared with WT mice. Absorbance was read at 460 nm. F: increased lung injury and inflammation as detected by histology evaluation. atg7 KO mice and WT mice were infected 5 × 105 CFU/mouse for 24 h. Inset shows the enlarged area for tissue injury. Mice were dissected, and lungs were embedded in formalin. Sections were analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The data were representative of 6 mice/group. RLU, relative luciferase units. Error bars represent SDs.

Kp infection has been previously shown to induce the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), whose accumulation may compromise lung injury and eventually lead to lung breakdown (11). Superoxide production in AM cells of atg7 KO mice showed increased oxidative stress vs. those of WT mice 24 h postinfection assessed by an NBT assay (Fig. 3D). To verify the data, a more quantitative dihydrodichlorofluorescein diacetate assay was used to further confirm the superoxide increase in atg7 KO AM cells following Kp infection (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that increased ROS may hamper cell survival by increasing apoptosis and may significantly damage the lung and other vital organs. We next evaluated myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the lung tissue of atg7 WT and KO mice to reflect neutrophil penetration, since MPO is a widely recognized influx for oxidation in physiological context. As expected, we noted increased MPO levels in the lung of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 3E). We also found that lipid peroxidation was significantly increased in the Kp-infected lungs of atg7 KO mice vs. those of WT mice (data not shown), which was consistent with the MPO assay and superoxide detection. Taken together, atg7 KO mice exhibit much greater lung injury than WT mice, indicating that loss of Atg7 results in inflammatory responses that may aggravate tissue injury.

As a direct measure of lung injury, we examined lung histology 24 h postinfection. We found that both atg7 KO mice and WT mice exhibited signs of pneumonia while exposed to Kp, whereas histological alterations and PMN infiltration were further intensified in the lungs of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that the loss of Atg7 in mice exacerbated the lung tissue injury after infection.

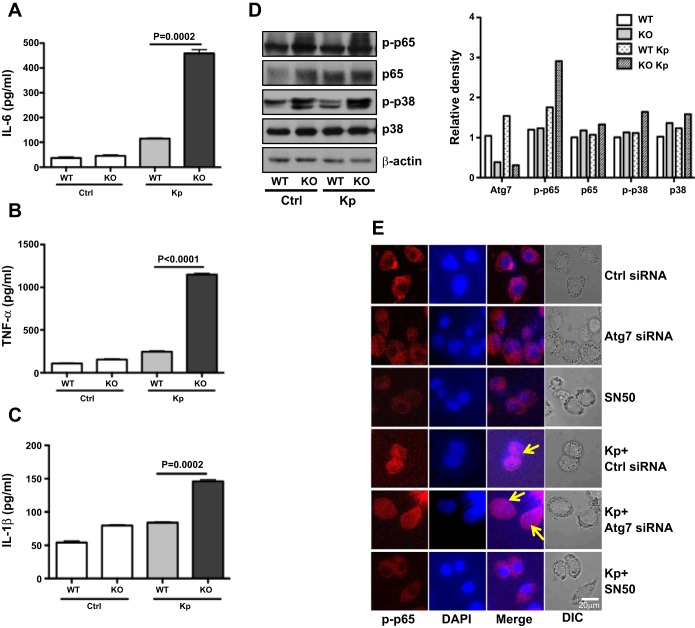

atg7 KO mice manifested altered inflammatory responses.

Atg7 has been implicated in bacterial-induced inflammatory responses. To reveal the inflammatory profile in our model, we determined some critical proinflammatory cytokines, an indicator of inflammatory responses, in BAL fluids and lungs at 24 h postinfection. BAL fluids of atg7 KO mice showed no significant change in inflammatory responses compared with those of WT mice. However, in atg7 KO mouse lungs, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were significantly elevated compared with those of WT mice as assayed by ELISA (P < 0.01, Fig. 4, A-C). To validate these data, protein levels of these quantified cytokines were also measured by Western blot analysis, and expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β protein was also found to be upregulated, especially TNF-α and IL-1β, with >10-fold increase (data not shown). Collectively, these data point out that atg7 KO mice manifested more intense proinflammatory responses following Kp infection than WT mice.

Fig. 4.

Kp infection induced intense inflammatory responses in atg7 KO mice. A–C: increased inflammatory cytokines in BALF of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice as assessed by ELISA. Mice (n = 6) were infected with 5 × 105 CFU/mouse Kp for 24 h. BAL fluid was collected, and cytokines were measured. Data were representative of three experiments with similar results. D: increased phosphor (p)-p38 and p-nuclear factor (NF)-κB (p65) of atg7 KO mice compared with WT mice as assessed by Western blotting. Frozen lung tissue of atg7 KO mice and WT mice at 24 h postinfection was lysed for protein assays. Gel data were quantified using densitometry with Image J software. Expression levels of the proteins were quantified relative to β-actin. The data were representative of two experiments. E: decreased nuclear translocation of NF-κB in Atg7 siRNA-transfected MH-S cells. Cells were transfected with Atg7 siRNA or control siRNA. After 24 h, cells were infected with Kp at MOI of 10:1 for 1 h. The localization of NF-κB was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence staining (arrows show the nuclear translocation). SN-50 (1.8 μM) was used to pretreat the cells for 0.5 h before infection. The data were representative of three experiments.

atg7 KO mice exhibited activated NF-κB and p38 MAPK by Kp infection.

To illustrate the underlying mechanism of the dysregulated inflammatory responses in atg7 KO mice, we analyzed the cell signaling proteins in the lung tissue by Western blotting assay (Fig. 4D). Our data showed that infection significantly increased the protein expression and phosphorylation (ser536) of NF-κB p65 subunit. We then attempted to identify the upstream regulator of NF-κB and found that p-p38 MAPK was greatly increased in atg7 KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4D) after Kp infection. Hence, these results indicate that the activation of p38/NF-κB signaling in atg7 KO mice may be a contributing factor for the intensified inflammatory responses. To further confirm the critical role of Atg7 in NF-κB activation, we used Atg7 siRNA-transfected MH-S cells to determine nuclear translocation. We found that Atg7 siRNA transfection markedly increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB vs. control siRNA (Fig. 4E). To validate this observation, NF-κB inhibitor SN-50 (1.8 μM) was used to pretreat the cells, which also abolished NF-κB translocation (Fig. 4E) and proinflammatory cytokine levels (data not shown). Our findings demonstrate that NF-κB activity is modulated by Atg7.

AM cells from atg7 KO mice manifested intensified inflammatory responses.

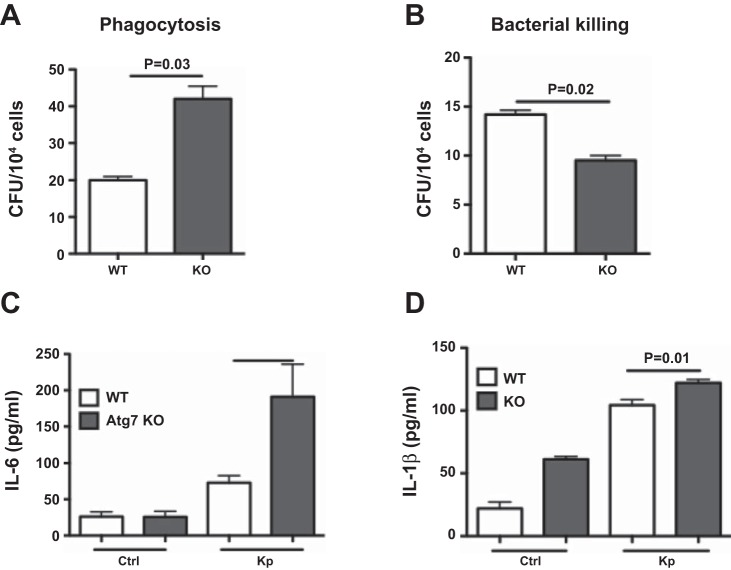

We further confirm the role of Atg7 in bacterial killing and inflammatory responses by primary macrophage cells. Bacterial Burden Assay demonstrated increased bacterial phagocytosis and decreased killing in AM cells of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice (Fig. 5, A and B). Bacterial killing in primary AM was similar to MH-S cells, whereas Kp phagocytosis in AM cells was not (Fig. 1D). These differences may be due to different characteristics of cell lines vs. primary cells, and indeed our recent studies showed that knocking down of another autophagy protein (FIP-200) also reduced MH-S cell phagocytosis (30). To examine the effect of Atg7 on inflammation, we measured cytokine levels and found that AM cells of atg7 KO mice had increased cytokine secretion (IL-6 and IL-1β) compared with that of WT mice using ELISA (Fig. 5, C and D). Collectively, atg7 deficiency significantly altered macrophage host defense in mouse models, which may contribute to the worsened phenotype.

Fig. 5.

Host defense of AM cells from atg7 KO mice is impaired. A and B: AM cells of atg7 KO mice showed increased bacterial phagocytosis and decreased killing after Kp infection, respectively. CFU assay was used to evaluate survived bacteria inside of the cells following polymyxin B treatment to kill surface bacteria. C and D: increased inflammatory cytokines in primary AM cells isolated from atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice after Kp infection as assessed by ELISA. Data were representative of three experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a typical phenotype of Kp infection in atg7 KO mice, including decreased survival, increased inflammatory response, and more severe lung injury compared with WT mice. Despite a variety of virulence factors that cause varying tissue abnormalities, we proposed that severely dysregulated cytokine responses and increased superoxide release contribute to this serious pathophysiology. Previously, similar phenotypes (increased susceptibility, increased production of cytokines, and elevated bacterial burdens) have been observed in atg7 KO mice infected with other pathogens, such as fungi and viruses (15, 27, 38). The current study suggests that Atg7 may contribute to critical host immune defense against Kp infection.

Atg7 is widely expressed in alveolar epithelial and lung macrophage cells (39). Previous studies have implicated the involvement of Atg7 in host responses to pathogen virulence factors (3, 18, 42); however, the role of Atg7 in inflammatory responses has not been elucidated. Our laboratory previously showed that Atg7 could influence the phagocytosis activity of another Gram-negative bacterium (P. aeruginosa) in macrophage cells (51). In the present study, using animal and cell culture models, we showed for the first time that Atg7 is indispensable in host defense against Kp infection, and autophagy defect could lead to a worsened outcome of Kp infection due to dysregulated inflammatory responses. Thus our studies indicate that Atg7 may have broad immunity against Gram-negative bacterial infection.

We found a differential role of Atg7 in bacterial phagocytosis killing by macrophages, showing increased bacterial phagocytosis and decreased killing in primary AM cells of atg7 KO mice compared with those of WT mice. Interestingly, Kp phagocytosis by primary AM was contradictory to cell line data (Figs. 5A and 1D). However, these results are in agreement with our recent studies in MH-S cells showing that knocking down of another critical autophagy protein (FIP-200) also reduced phagocytosis (30). Similarly, a previous study showed that knocking down Atg7 in monocytes showed decreased phagocytosis activity after challenging with CSF-1 (17). siRNA strategies may not completely and stably deplete the protein expression, whereas KO mice may exhibit complex phenotypes resulting from compensatory activities. Nevertheless, combination of these two models generates relatively unbiased data, thus closely modeling physiological relevance of our observations.

To probe the underlying mechanism, we determined the change in ROS that may be responsible for bacterial clearance by phagocytes. Previous studies have shown that Atg7 in tetrandrine-induced autophagy is ROS dependent during human hepatocellular carcinogenesis (8). Our results also showed significantly increased ROS levels in AM cells of atg7 KO mice, which may impair mitochondrial membrane potential compared with those in WT mice. These data argue that Atg7 may act as a downregulator in superoxide production and release, whereas an elevated oxidative stress in atg7 KO mice may be associated with lung injury and systemic bacterial infection. We also detected the superoxide production in MH-S cells and MLE-12 cells after silencing Atg7 with siRNA, and the superoxide production was increased along with an increased bacterial burden under Atg7 knockdown conditions, which is consistent with the animal AM data (data not shown). Together, these observations demonstrate that machinery in bacterial clearance is markedly impaired in atg7-deficient mice in the case of Kp infection. However, Atg7's role in human cells has not been described and warrants future investigations. Because we have relevant experience in human lung epithelial cells, we will further evaluate the relevant pathway in cell lines such as A549 (10) and primary human lung epithelial cells.

Another major contributing factor to lung injury and mortality is a heightened inflammatory response. Significantly, lungs and BAL fluid of atg7 KO mice exhibited an increase in proinflammatory cytokines. We found that, although IL-1β was also increased, the change of IL-6 was more significant, suggesting that an IL-6 dominant inflammatory response may be related to Atg7 function. Indeed a previous study also revealed that IL-6 is involved in the Atg7 pathway (37). Previously, similar results (increased proinflammatory cytokines) have also been observed in the intestine in atg7 KO mice (16). It has been increasingly recognized that lung epithelial cells can contribute to the production of cytokines (2, 43), which may be a further topic. Furthermore, phagocytes (e.g., macrophages and neutrophils) are traditionally regarded as the main players of inflammatory responses (35). Thus intensified superoxide or cytokines in both epithelia and phagocytes together led to exceedingly heightened inflammatory responses in atg7 KO mice, which warrants further investigations.

To illustrate the mechanism for the dysregulated inflammatory responses in atg7 KO mice, we assessed potential cell-signaling pathways in the lung tissue following infection. Interestingly, we observed marked activation of NF-κB, which has been widely recognized as a major transcription factor for cytokine production in alveolar epithelial cells.

p38 MAPK is one of the major signaling molecules that plays a pivotal role in most types of cytokine production in various cells and different conditions (1, 49). In the Kp model, we also found that p38 and NF-κB were significantly activated in atg7 KO mice following Kp infection. Atg7 has been shown to interact with NF-κB directly through molecular interactions, and Atg7 deficiency may impact NF-κB activity (7). To date, no studies have linked Atg7 with the NF-κB pathway in response to any respiratory pathogen. To this end, we used Atg7 siRNA to determine the nuclear translocation and found that Atg7 knockdown markedly increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB vs. controls (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, NF-κB inhibitor SN-50 (1.8 μM) also reduced NF-κB translocation (Fig. 4E). Our findings indicate that NF-κB activity may be modulated by Atg7, which may be relevant to the altered inflammatory response. The detailed mechanism is unclear and is worth further study.

In our present study, we focused on the potential role of Atg7 in Kp infection and revealed its regulatory mechanism in Kp-induced inflammatory response. However, we cannot exclude the contribution of other autophagy-related genes to this mechanism during Kp infection. It has been reported that mouse cells lacking Atg5 or Atg7 can still form autophagosomes/autolysosomes and perform autophagy-mediated protein degradation after challenging with certain stressors (34). Similarly, we noted that other autophagy-related genes are involved in Kp infection, which is currently under investigation. Furthermore, other mechanisms rather than inflammatory responses may also contribute to Atg7's role in immune defense against infection.

In conclusion, we present the first disease phenotype of Kp infection in atg7 KO mice, and our data identify an important role for Atg7 in innate immunity against Gram-negative bacterium Kp in KO mice. atg7 deficiency impaired the phagocytic ability in AM and other immune functions, resulting in sustained infiltration of PMN cells into the lung and an intense inflammatory response through the p38/NF-κB pathway. Collectively, these observations provide new insight into the role of Atg7 in innate immunity against Kp, indicating a novel target for potential therapeutic interventions.

GRANTS

This project was supported by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Grant No. 103007 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants AI-101973-01 and AI-097532-01A1 to M. Wu.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.Y. and M.W. conception and design of research; Y.Y., X.L., W.W., K.C.O., Y.L., C.G., S.T., and X.Z. performed experiments; Y.Y., C.G., and X.Z. analyzed data; Y.Y., Y.L., S.T., and M.W. interpreted results of experiments; Y.Y. prepared figures; Y.Y. drafted manuscript; Y.Y. and M.W. edited and revised manuscript; Y.Y. and M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Rolling of UND imaging core for help with confocal imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adcock IM, Chung KF, Caramori G, Ito K. Kinase inhibitors and airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol 533: 118–132, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano H, Morimoto K, Senba M, Wang H, Ishida Y, Kumatori A, Yoshimine H, Oishi K, Mukaida N, Nagatake T. Essential contribution of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/C-C chemokine ligand-2 to resolution and repair processes in acute bacterial pneumonia. J Immunol 172: 398–409, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amer AO, Byrne BG, Swanson MS. Macrophages rapidly transfer pathogens from lipid raft vacuoles to autophagosomes. Autophagy 1: 53–58, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler B, Cerami A. The biology of cachectin/TNF–a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol 7: 625–655, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Hui L, Geiger NH, Haughey NJ, Geiger JD. Endolysosome involvement in HIV-1 transactivator protein-induced neuronal amyloid beta production. Neurobiol Aging 34: 2370–2378, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng X, Weerapana E, Ulanovskaya O, Sun F, Liang H, Ji Q, Ye Y, Fu Y, Zhou L, Li J, Zhang H, Wang C, Alvarez S, Hicks LM, Lan L, Wu M, Cravatt BF, He C. Proteome-wide quantification and characterization of oxidation-sensitive cysteines in pathogenic bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 13: 358–370, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujishima Y, Nishiumi S, Masuda A, Inoue J, Nguyen NM, Irino Y, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Kutsumi H, Azuma T, Yoshida M. Autophagy in the intestinal epithelium reduces endotoxin-induced inflammatory responses by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation. Arch Biochem Biophys 506: 223–235, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong K, Chen C, Zhan Y, Chen Y, Huang Z, Li W. Autophagy-related gene 7 (ATG7) and reactive oxygen species/extracellular signal-regulated kinase regulate tetrandrine-induced autophagy in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biol Chem 287: 35576–35588, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haranaga S, Yamaguchi H, Ikejima H, Friedman H, Yamamoto Y. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection of alveolar macrophages: a model. J Infect Dis 187: 1107–1115, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He YH, Wu M, Kobune M, Xu Y, Kelley MR, Martin WJ., 2nd. Expression of yeast apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APN1) protects lung epithelial cells from bleomycin toxicity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 25: 692–698, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickman-Davis JM, O'Reilly P, Davis IC, Peti-Peterdi J, Davis G, Young KR, Devlin RB, Matalon S. Killing of Klebsiella pneumoniae by human alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L944–L956, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui L, Chen X, Bhatt D, Geiger NH, Rosenberger TA, Haughey NJ, Masino SA, Geiger JD. Ketone bodies protection against HIV-1 Tat-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem 122: 382–391, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui L, Chen X, Geiger JD. Endolysosome involvement in LDL cholesterol-induced Alzheimer's disease-like pathology in primary cultured neurons. Life Sci 91: 1159–1168, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui L, Chen X, Haughey NJ, Geiger JD. Role of endolysosomes in HIV-1 Tat-induced neurotoxicity. ASN Neuro 4: 243–252, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang S, Maloney NS, Bruinsma MW, Goel G, Duan E, Zhang L, Shrestha B, Diamond MS, Dani A, Sosnovtsev SV, Green KY, Lopez-Otin C, Xavier RJ, Thackray LB, Virgin HW. Nondegradative role of Atg5-Atg12/Atg16L1 autophagy protein complex in antiviral activity of interferon gamma. Cell Host Microbe 11: 397–409, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue J, Nishiumi S, Fujishima Y, Masuda A, Shiomi H, Yamamoto K, Nishida M, Azuma T, Yoshida M. Autophagy in the intestinal epithelium regulates Citrobacter rodentium infection. Arch Biochem Biophys 521: 95–101, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacquel A, Obba S, Boyer L, Dufies M, Robert G, Gounon P, Lemichez E, Luciano F, Solary E, Auberger P. Autophagy is required for CSF-1-induced macrophagic differentiation and acquisition of phagocytic functions. Blood 119: 4527–4531, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia K, Thomas C, Akbar M, Sun Q, Adams-Huet B, Gilpin C, Levine B. Autophagy genes protect against Salmonella typhimurium infection and mediate insulin signaling-regulated pathogen resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 14564–14569, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia W, Pua HH, Li QJ, He YW. Autophagy regulates endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and calcium mobilization in T lymphocytes. J Immunol 186: 1564–1574, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones RN. Microbial etiologies of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 51, Suppl 1: S81–S87, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannan S, Audet A, Huang H, Chen LJ, Wu M. Cholesterol-rich membrane rafts and Lyn are involved in phagocytosis during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Immunol 180: 2396–2408, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannan S, Pang H, Foster DC, Rao Z, Wu M. Human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase increases resistance to hyperoxic cytotoxicity in lung epithelial cells and involvement with altered MAPK activity. Cell Death Differ 13: 311–323, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3: 452–460, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 169: 425–434, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432: 1032–1036, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawlor MS, Hsu J, Rick PD, Miller VL. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence determinants using an intranasal infection model. Mol Microbiol 58: 1054–1073, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenz HD, Vierstra RD, Nurnberger T, Gust AA. ATG7 contributes to plant basal immunity towards fungal infection. Plant Signal Behav 6: 1040–1042, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 6: 463–477, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132: 27–42, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Gan CP, Zhang S, Zhou XK, LIXF, Wei YQ, Yang JL, Wu M. FIP200 is involved in murine pseudomonas infection by regulating HMGB1 intracellular translocation. Cell Physiol Biochem 33: 1733–1744, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, Dipaola RS, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell 137: 1062–1075, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mbawuike IN, Herscowitz HB. MH-S, a murine alveolar macrophage cell line: morphological, cytochemical, and functional characteristics. J Leukoc Biol 46: 119–127, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizgerd JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med 358: 716–727, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, Komatsu M, Otsu K, Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461: 654–658, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozaki T, Maeda M, Hayashi H, Nakamura Y, Moriguchi H, Kamei T, Yasuoka S, Ogura T. Role of alveolar macrophages in the neutrophil-dependent defense system against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in the lower respiratory tract. Amplifying effect of muramyl dipeptide analog. Am Rev Respir Dis 140: 1595–1601, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan J, Pei DS, Yin XH, Hui L, Zhang GY. Involvement of oxidative stress in the rapid Akt1 regulating a JNK scaffold during ischemia in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 392: 47–51, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pastore N, Blomenkamp K, Annunziata F, Piccolo P, Mithbaokar P, Maria Sepe R, Vetrini F, Palmer D, Ng P, Polishchuk E, Iacobacci S, Polishchuk R, Teckman J, Ballabio A, Brunetti-Pierri N. Gene transfer of master autophagy regulator TFEB results in clearance of toxic protein and correction of hepatic disease in alpha-1-anti-trypsin deficiency. EMBO Mol Med 5: 397–412, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pei Y, Chen ZP, Ju HQ, Komatsu M, Ji YH, Liu G, Guo CW, Zhang YJ, Yang CR, Wang YF, Kitazato K. Autophagy is involved in anti-viral activity of pentagalloylglucose (PGG) against Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 405: 186–191, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy in the lung. Proc Am Thorac Soc 7: 13–21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sha WC. Regulation of immune responses by NF-kappa B/Rel transcription factor. J Exp Med 187: 143–146, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shrivastava S, Raychoudhuri A, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Knockdown of autophagy enhances the innate immune response in hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes. Hepatology 53: 406–414, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanida I, Fukasawa M, Ueno T, Kominami E, Wakita T, Hanada K. Knockdown of autophagy-related gene decreases the production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Autophagy 5: 937–945, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorley AJ, Goldstraw P, Young A, Tetley TD. Primary human alveolar type II epithelial cell CCL20 (macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha)-induced dendritic cell migration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 262–267, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vooijs M, Jonkers J, Berns A. A highly efficient ligand-regulated Cre recombinase mouse line shows that LoxP recombination is position dependent. EMBO Rep 2: 292–297, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu M, Audet A, Cusic J, Seeger D, Cochran R, Ghribi O. Broad DNA repair responses in neural injury are associated with activation of the IL-6 pathway in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Neurochem 111: 1011–1021, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.Wu M, Huang H, Zhang W, Kannan S, Weaver A, McKibben M, Herington D, Zeng H, Gao H. Host DNA repair proteins in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in lung epithelial cells and in mice. Infect Immun 79: 75–87, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu M, Hussain S, He YH, Pasula R, Smith PA, Martin WJ., 2nd. Genetically engineered macrophages expressing IFN-gamma restore alveolar immune function in scid mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14589–14594, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu M, Pasula R, Smith PA, Martin WJ., 2nd. Mapping alveolar binding sites in vivo using phage peptide libraries. Gene Ther 10: 1429–1436, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshizumi M, Kimura H, Okayama Y, Nishina A, Noda M, Tsukagoshi H, Kozawa K, Kurabayashi M. Relationships between cytokine profiles and signaling pathways (IkappaB kinase and p38 MAPK) in parainfluenza virus-infected lung fibroblasts (Abstract). Front Microbiol 1: 124, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan K, Huang C, Fox J, Gaid M, Weaver A, Li G, Singh BB, Gao H, Wu M. Elevated inflammatory response in caveolin-1-deficient mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection is mediated by STAT3 protein and nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB). J Biol Chem 286: 21814–21825, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan K, Huang C, Fox J, Laturnus D, Carlson E, Zhang B, Yin Q, Gao H, Wu M. Autophagy plays an essential role in the clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by alveolar macrophages. J Cell Sci 125: 507–515, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]