Abstract

We developed an alternative approach to teach diabetes mellitus in our practical classes, replacing laboratory animals. We used custom rats made of cloth, which have a ventral zipper that allows stuffing with glass marbles to reach different weights. Three mock rats per group were placed into metabolic cages with real food and water and with test tubes containing artificial urine, simulating a sample collection of 24 h. For each cage, we also provided other test tubes with artificial blood and urine, simulating different levels of hyperglycemia. The artificial “diabetic” urine contained different amounts of anhydrous glucose and acetone to simulate two different levels of glycosuria and ketonuria. The simulated urine of a nondiabetic rat was prepared without the addition of glucose or acetone. An Accu-Chek system is used to analyze glycemia, and glycosuria and ketonuria intensity were analyzed by means of a Urocolor bioassay. In the laboratory classroom, students were told that they would receive three rats to find out which one has type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. To do so, they had to weigh the animals, quantify the water and food ingestion, and analyze the artificial blood and urine for glycemia, glycosuria, and ketonuria. Only at the end of class did we reveal that the urine and blood were artificial. Students were instructed to plot the data in a table, discuss the results within their group, and write an individual report. We have already used this practical class with 300 students, without a single student refusing to participate.

Keywords: alternative physiology class, insulin effects, diabetes types, ethical concerns

diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disease identified by the medical community as a major problem due to its high prevalence worldwide. Currently, it is estimated that 381 million people have DM, and the number of cases will presumably increase ∼55% through 2035 (8). Furthermore, studies have shown that 45.8% of all DM cases are undiagnosed, with developing countries accounting for the largest portion of this rate (3). In addition, DM represents a powerful economic burden all over the world, with estimated annual costs reaching up US$ 174 billion (12). The direct costs (including inpatient cost) may also attain US$ 14,060 per patient per year (12).

There are two forms of DM: type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent). Although there are different etiologies, both DM types cause hyperglycemia, polyphagy, polydipsia, poliuria, ketonuria, weight loss, and long-term complications, such as retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, artherosclerosis, and impaired cicatrization (1, 14). In addition to its well-known systemic effects, DM can also cause several oral alterations, particularly in patients with poor glycemic control. For example, there is a bidirectional relationship with periodontal disease, in which DM is a risk factor for the onset and development of periodontal disease, and this, in turn, may exacerbate the systemic condition (11, 14). Plausible biological mechanisms underlying this interrelation have been described, emphasizing the importance of diagnosis, monitoring, clinical laboratory tests, and medication to control the disease (9, 13). This makes it a requirement that DM be addressed under several aspects and in various disciplines of biomedical sciences courses, including dentistry and pharmacy.

To teach aspects of DM in our physiology course, we usually have a practical class after a lecture on pancreas function to emphasize the role of insulin and the changes observed during the disease. In this way, we can provide scientific explanations for these changes as well as create space for discussion about diagnostic, clinical, and laboratory examinations and treatments as well as also current research on the disease. Until recently, practical classes were taught using alloxan-induced diabetic rats through intravenous injection. At that time, during the practical class, animals were presented to students in a metabolic cage, and, after a brief explanation, animals were weighed, overnight food and water consumption were determined, and animals had a blood sample taken from a small incision in the tail to determine glucose levels by means of a spectrophotometer. Insulin was administered, and, 1 h later, blood was again collected for glycemic analysis. During the class, the odor of diabetic animals, which normally have diarrhea, was very unpleasant, and the animals' discomfort during blood collection was evident. This actually distracted students from the central focus of the class, which was to understand DM, and we experienced discussions among students who often wondered about the necessity of using animals in such classes. To understand the level of discomfort, we then decided to analyze the perceptions of students of pharmacy and dentistry courses about the use of animals in practical classes (15). The results showed that although some students found it important to use diabetic animals for learning, most experienced discomfort during the class and were in favor of replacing the animals with alternative material. Recently, some colleagues reported that they successfully used small stuffed rats in practical classes to teach thyroid function in a simulated detective case (10). These findings prompted us to develop teaching material using artificial animals and artificial blood and urine as an alternative method for use in our DM practical classes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol.

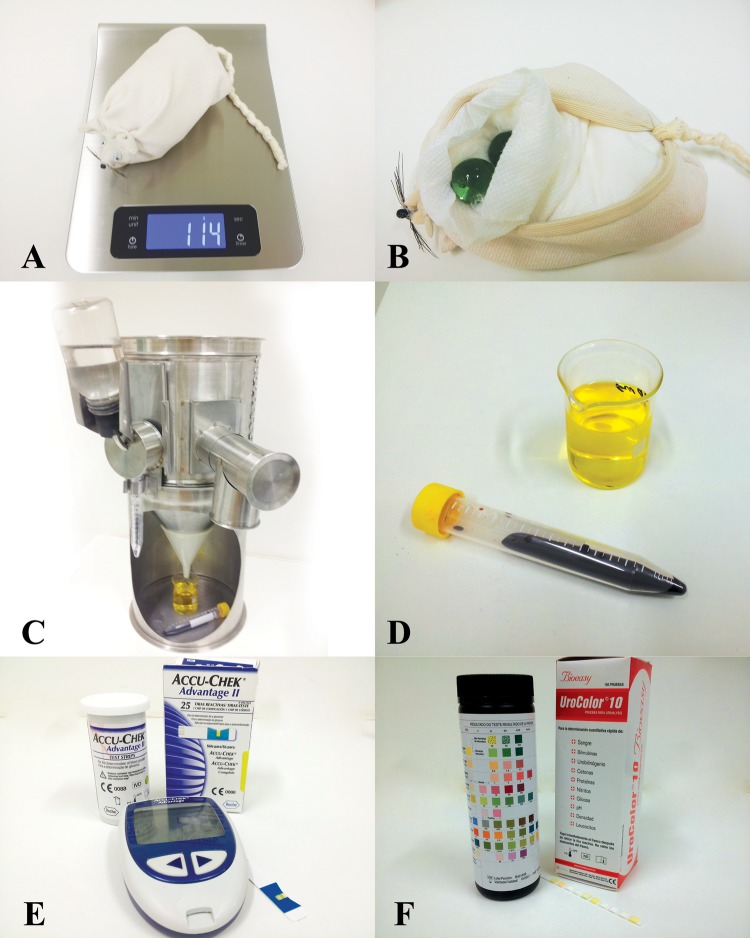

For each group of students, we prepared three small mock rats made of cloth. Mock rats had a ventral zipper that allowed stuffing with glass marbles to reach different weights (Fig. 1, A and B). To simulate a real situation, mock rats were placed inside metabolic cages (Insight Ltda E-310) with real food and water, simulating a sample collection over a 24-h period. In each cage, we placed test tubes containing artificial urine and blood (Fig. 1, C and D). After a short explanation based on the written protocol distributed to students before the practical class, students were asked to find out which rat had DM type 1 or type 2 and the rat that was normal. Before students started the data collection, we provided the initial body weights of the animals and the amount of water and food inserted in the metabolic cage in the previous 24 h. Animals and food were weighed on a balance, the water drunk was measured with a measuring cylinder, and the glycemia level was determined by an Accu-Chek advantage system (Roche). The presence of glucose and ketone in urine were detected by means of Urocolor test strips (Bioeasy Diagnóstica) (Fig. 1, E and F). Only when measurements were finished did we reveal that the urine and blood were artificial. Collected data were plotted in a table, and the results were discussed in the group. Students were asked to deliver an individual report containing the table with the data and the answer to five questions related to DM. More recently, with the acquisition of interactive devices by our institution, we analyzed the degree of students' satisfaction with this practical class.

Fig. 1.

A: a mock rat being weighed. B: a mock rat stuffed with marbles. C: metabolic cage with water and food and with artificial blood and urine in test tubes. D: artificial blood and urine in test tubes outside of the metabolic cage. E: Accu-Chek system. F: Urocolor bioassay.

Artificial blood and urine.

The artificial blood consisted of a solution containing Congo red (3.48 mg/ml), sodium fluoride (5 mg/ml), glycerol (100 μl/ml), and different amounts of anhydrous glucose to simulate normal glycemia (1.3 mg/ml), hyperglycemia (2 mg/ml), and very high hyperglycemia (3 mg/ml).The artificial urine contained water (44 ml), acetone (200 μl/ml), metanil yellow (21. 8 μg/ml), and anhydrous glucose (≥0.545 mg/ml) in different amounts to simulate two different levels of glycosuria. The simulated urine for a normal rat was prepared without the addition of glucose or acetone. The levels of glycemia and of glycosuria or ketonuria reached are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Composition of artificial blood and glycemia reached

| Rat 1 | Rat 2 | Rat 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial blood composition | |||

| Congo red, mg | 34.8 | 34.8 | 34.8 |

| Anhydrous glucose, mg | 13.0 | 20.0 | 30.0 |

| Glycerol, ml | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sodium fluoride, mg | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Distilled water, ml | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Glycemia reached, mg/dl | 80 | 150 | 250 |

Table 2.

Composition of artificial urine and results of ketonuria and glycosuria

| Rat 1 | Rat 2 | Rat 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial urine composition | |||

| Metanil yellow, mg | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Acetone, ml | 0 | 0,5 | 1,5 |

| Anhydrous glucose, mg | 0 | 40 | 90 |

| Water, ml | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Glycosuria | None | ++ | +++ |

| Ketonuria | None | ++ | +++ |

++, strong; +++, very strong.

Glycemia, glycosuria, and ketonuria.

An Accu-Chek advantage system was used for glycemia analysis (Fig. 1E). A small drop of fake blood was placed on the test strip and shortly thereafter was introduced in the system, which is usually used by diabetic patients to monitor their glycemia. For glycosuria and ketonuria, we used test strips (Urocolor bioassay; Fig. 1F).

RESULTS

When students started the hands-on work, we provided the initial body weights of the artificial animals to the students, but we did not reveal which animal was the control, DM type 1, or DM type 2 animal. We explained that each rat had been given 150 ml of water and 100 g of food the day before the class. Students then weighed the mock animals to define the weight gain and food and water ingestion of each rat. Subsequently, they calculated the results, which were expressed per 100 g body wt.

As expected, values for blood and urine parameters were higher for the simulated DM type 1 rat (rat 3). The blood of the control rat (rat 1) had a glycemia of 80 mg/100 ml, and those of simulated DM type 2 and type 1 glycemic rats were 150 and 250 mg/dl (rats 2 and 3), respectively. Artificial urine results showed no glycosuria or ketonuria for the control rat, whereas for DM rats, glycosuria readings were 100 mg/dl (strong) and 300 mg/dl (very strong) and ketonuria levels were 50 mg/dl (strong) and 100 mg/dl (very strong) in DM type 2 and type 1 rats (rats 2 and 3), respectively. After plotting the results in a table (Table 3), students were encouraged to discuss in their group the clinical signs and symptoms of each rat and write an individual report explaining the causes of the observed hyperglycemia, polydiuresis, polydipsia, polyphagia, glycosuria, and ketonuria in the DM rats. Moreover, the fact that rat 2 simulated an obese animal gave students the opportunity to discuss the differences between DM type 1 and type 2, including results from current research done in our institution.

Table 3.

Observed results based on the initial parameters

| Rat 1 | Rat 2 | Rat 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary volume, ml·24 h−1·100 g body wt−1 | 51.70 | 30.48 | 19.80 |

| Food intake, g·24 h−1·100 g body wt−1 | 34.48 | 18.29 | 11.90 |

| Water intake, ml·24 h−1·100 g body wt−1 | 47.40 | 24.39 | 19.84 |

| Glycemia, mg/100 ml | 300 | 150 | 80 |

| Glycosuria | +++ | ++ | None |

| Ketonuria | +++ | ++ | None |

| Change in body weight, mg | 26 | 74 | 36 |

DISCUSSION

Here, we present an alternative practical class that replaced laboratory animals for teaching DM in a physiology course. This practical lesson was designed in the past using living animals, but the use of artificial rats and simulated urine and blood did not prevent students from engaging in discussions about the systemic role of insulin and consequences of an impaired insulin secretion or insulin resistance in the organism. Furthermore, students could see the difference between the aims of teaching DM syndromes in a practical class using an alternative approach. They also had an opportunity to discuss the results of ongoing research in our institution and in laboratories around the world. As in the past, when we used laboratory animals, students had the opportunity to interact with each other and discuss the results in their groups. In this way, they could connect the clinical signs and symptoms they observed in the alternative rat model to what they had learned in the theoretical class. Moreover, as we could add a mock rat with simulated obesity (not done in the earlier classes), students could also better discuss the differences between DM types. A preliminary opinion analysis using a Likert scale showed that most students were completely satisfied with this alternative practical class. Moreover, they agreed that it did not undermine their learning (anecdotal reports). Alternative approaches and models are generally developed and used to improve teaching and learning, and there are many published academic studies reporting on the use of alternative teaching tools and comparing these with traditional practical physiology lessons using laboratory animals.

These studies provide evidence that students using alternative methods learn equally well, or sometimes better, than those using laboratory animals (2, 4, 6, 17). In fact, teaching models that do not involve harmful animal experimentation or death during class seem to be beneficial to student learning (18). When we used laboratory rats in the past, many of the students were worried about the pain or discomfort that the animals would experience during the practical class. This usually distracted them from the main objective, which was to discuss DM, and they would instead to get involved in discussions about ethical issues. Although we think that ethical issues are important and should be incorporated within a physiology course, we believe that the appropriate way to do so would be to offer specific lectures on this topic. Despite their importance, a recent survey showed that in 45 universities around the world with an undergraduate medical course, there is a paucity of formal ethical teaching in the physiology curriculum (7). To overcome the need for classes on this subject, our institution recently incorporated a bioethical discipline in the dentistry course curriculum. We now have the opportunity to teach students about ethical issues involving animal use for research or learning. By teaching about replacement, reduction and refinement (16), we can increase students' perceptions of the need to improve animal welfare and where and how to refine, replace, and reduce the number of animals used for research and teaching (19). The other advantage of this class is that it can easily be adapted in any institution, especially those with fewer resources, because it does not require technical support, equipment, and adequate physical space when working with animals. Even if an institution does not have a metabolic cage (although we consider that it would be better to show how animals are actually kept in a real experiment), the class can be performed by just presenting the artificial animal in an ordinary animal holding cage and with artificial blood and urine with different levels of glucose or ketones and with real food and water. Moreover, to motivate students even more, we can vary the identity of the rats that are assigned to the groups so that it doesn't become obvious which rat is diabetic or control. Therefore, we conclude that this practical class fully meets all teaching objectives, besides being beneficial to the students and institutions. Moreover, by having no distracting discomfort, students can experience excitement and joy in this class, a very important component in learning (5).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: P.J.B. and M.J.A.R. conception and design of research; P.J.B., L.F.T., M.F.S., and M.J.A.R. performed experiments; P.J.B., L.F.T., and M.J.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; L.F.T. and M.J.A.R. prepared figures; L.F.T. and M.J.A.R. approved final version of manuscript; M.F.S. and M.J.A.R. analyzed data; M.F.S. and M.J.A.R. interpreted results of experiments; M.J.A.R. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the students who participated for the first time in this laboratory class.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 36: 67–74, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balcombe J. The Use of Animals in Higher Education. Problems, Alternatives & Recommendations. Washington, DC: The Humane Society Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beagley J, Guariguata L, Weil C, Motala AA. Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103: 150–160, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dewhurst DG, Hardcastle J, Hardcastle PT, Stuart E. Comparison of a computer simulation program and a traditional laboratory practical class for teaching the principles of intestinal absorption. Adv Physiol Educ 12: 95–104, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DiCarlo SE. Too much content, not enough thinking, and too little FUN! Adv Physiol Educ 33: 257–264, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diniz R, Duarte AL, Oliveira CA, Romiti M. Animais em aulas práticas: podemos substituí-los com a mesma qualidade de ensino? Revista Brasileira Educ Méd 30: 31–40, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goswami N, Batzel JJ, Hinghofer-Szalkay H. Assessing formal teaching of ethics in physiology: an empirical survey, patterns, and recommendations. Adv Physiol Educ 36: 188–191, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103: 137–149, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, Cox CE, Duker P, Edwards L, Fisher EB, Hanson L, Kent D, Kolb L, McLaughlin S, Orzeck E, Piette JD, Rhinehart AS, Rothman R, Sklaroff S, Tomky D, Youssef G; 2012 Standards Revision Task Force. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care 36: 100–108, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lelis-Santos C, Giannocco G, Nunes MT. The case of thyroid hormones: how to learn physiology by solving a detective case. Adv Physiol Educ 35: 219–226, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc 137: 26–31, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ng CS, Lee JY, Toh MP, Ko Y. Cost-of-illness studies of diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract; 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oppermann RV, Weidlich P, Musskopf ML. Periodontal disease and systemic complications. Braz Oral Res 26: 39–47, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rocha MJ, Taba M, Jr, Costa PP. Influência da insulina/diabetes mellitus nas estruturas bucomaxilofaciais. In: Hormônios Sistêmicos e as Estruturas Bucomaxilofaciais, edited by Motta AC, Rocha MJ, Taba M., Jr Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil: TOTA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rochelle AB, Silva RH, Rocha MJ. Students' perception about the use of animals during practical classes (Abstract). Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil: 47th Annual Meeting of Sociedade Brasileira de Fisiologia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Russell WM, Burch RL. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. London: Methuen, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith A, Fosse R, Dewhurst D, Smith K. Educational simulation models in the biomedical sciences. ILAR J 38: 82–88, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Valk J, Dewhurst D, Hughes I, Atkinson J, Balcombe J, Braun H, Gabrielson K, Gruber F, Miles J, Nab J, Nardi J, van Wilgenburg H, Zinko U, Zurlo J. Alternatives to the use of animals in higher education the report and recommendations of Ecvam workshop 33. Altern Lab Anim 27: 30–52, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whittall H. Information on the 3Rs in animal research publications is crucial. Am J Bioethics 9: 60–61, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]