Abstract

While there are several tools to study learning styles of students, the visual-aural-read/write-kinesthetic (VARK) questionnaire is a simple, freely available, easy to administer tool that encourages students to describe their behavior in a manner they can identify with and accept. The aim is to understand the preferred sensory modality (or modalities) of students for learning. Teachers can use this knowledge to facilitate student learning. Moreover, students themselves can use this knowledge to change their learning habits. Five hundred undergraduate students belonging to two consecutive batches in their second year of undergraduate medical training were invited to participate in the exercise. Consenting students (415 students, 83%) were administered a printed form of version 7.0 of the VARK questionnaire. Besides the questionnaire, we also collected demographic data, academic performance data (marks obtained in 10th and 12th grades and last university examination), and self-perceived learning style preferences. The majority of students in our study had multiple learning preferences (68.7%). The predominant sensory modality of learning was aural (45.5%) and kinesthetic (33.1%). The learning style preference was not influenced by either sex or previous academic performance. Although we use a combination of teaching methods, there has not been an active effort to determine whether these adequately address the different types of learners. We hope these data will help us better our course contents and make learning a more fruitful experience.

Keywords: visual-aural-read/write-kinesthetic, learning style, sex, academic performance

that students differ in their preferences of various modalities of learning is a fact unlikely to surprise any teacher. Yet, the utilization of this knowledge in a formal way to enhance the teaching process or learning environment has been almost absent until recently. In medical education, the emphasis on covering a fixed syllabus, often extensive, in a limited time period with the time-tested method of didactic lecture provided little scope for assessment of learning styles and modification of teaching styles. However, with the growing interest in newer teaching and learning methods worldwide, which is reflected in current Medical Council of India directives for undergraduate medical education, it is an opportune moment to change the age-old teaching styles with due diligence (10). While there are several tools to study learning styles of students, the visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic (VARK) questionnaire is a simple, freely available, easy to administer tool that encourages students to describe their behavior in a manner they can identify with and accept (7). The aim is to understand the preferred sensory modality (or modalities) of students for learning. The questionnaire is designed to identify the following four sensory modalities: visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic (8) (hence the acronym VARK). Teachers can use this knowledge to facilitate student learning. Moreover, students themselves can use this knowledge to change their learning habits.

Kasturba Medical College in Mangalore is a constituent college of Manipal University in Karnataka, India. It caters to the medical education needs of students from all over the country. Excellence in medical education is a constant endeavor rather than a milestone. Newer teaching learning techniques are being tried with a gradual shift of emphasis away from passive to active learning. Hence, a formal attempt was made to study the learning styles of two consecutive batches of second-year undergraduate medical students. Data from earlier studies have shown a possible influence of sex and academic performance on learning styles. However, the results have been conflicting, with some studies suggesting a sex difference in learning style preference, whereas others failed to demonstrate any difference (3, 10, 11). Also, differing sensory modality preferences for learning among students would likely be assumed to result in differing academic performance in a teaching environment that is not diverse and hence does not adequately address all types of learners. However, studies have failed to uniformly demonstrate an effect of learning style preference on academic performance (1, 2, 4). To the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted in India that addresses the issue of sex and academic performance with regard to learning style preference. Students of Kasturba Medical College have diverse geographic and cultural backgrounds. The study of learning style preferences among this student population using the VARK questionnaire and determining the influence of sex and academic performance is likely to add on to our knowledge of these factors that potentially influence learning style.

METHODS

This study was initiated following the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee. It was performed at the Department of Pharmacology at Kasturba Medical College. Five hundred undergraduate students belonging to two consecutive batches in their second-year of graduate medical training (after having completed the physiology, biochemistry, and anatomy courses in their first year) were invited to participate in the exercise. No incentive was given for participation. The purpose of the study was explained to the students, and written informed consent was obtained before the VARK questionnaire was administered. Besides the questionnaire, we also collected demographic data, self-reported academic performance data (marks obtained in 10th and 12th grades of high school and first-year university medical examination), and self-perceived learning style preferences. The self-perceived learning style preference was identified along with demographic and academic performance data. Participants were asked to describe their learning style(s) by choosing from the following options: 1) visual (learning from graphs, charts, flow diagrams, and demos); 2) aural (learning from speech, lectures, and discussions); 3) reading/writing (learning from reading and writing); and 4) kinesthetic (learning from performing an activity, touch, hearing, smell, taste, and sight). Version 7.0 of the VARK questionnaire in a printed form was used (8). It consisted of 16 questions with 4 options for each. Each option correlates to a particular sensory modality preference. Hence, the modality that received the highest marks was the preferred sensory modality. Since students were free to select more than one option, multiple modalities of varying combinations could be obtained. The questions describe situations of common occurrence in daily life, thereby relating to an individual's learning experience. Students were instructed to choose the answer that best explained their preference and circle the letter(s) next to it. They could choose more than one option or leave blank any question that they felt was not applicable to them. Questionnaires were evaluated on the basis of previously validated scoring instructions and a chart (8). Since each of the answers represents a sensory modality preference, the same was calculated for an individual participant by adding up the responses for all 16 questions. The score for each VARK component for the entire study sample was added up and divided by the total number of study participants to obtain mean scores. The entire exercise was completed in 15–20 min, after which the students were asked to return the questionnaire with demographic data and other details.

Statistical analyses.

Sensory modality preferences/VARK mode distributions are expressed as percentages of students in each category. Scores of individual VARK components are expressed as means ± SD. Comparison of VARK scores based on sex and academic performance was done using an independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, respectively. Comparison of unimodal sensory modality preference and VARK mode distribution among both sexes was done using a χ2-test. SPSS (version 11.5) was used for statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 500 undergraduate students invited to participate in the exercise, 415 students (83%) consented to provide demographic details and answer the VARK questionnaire. Of these, 236 students (56.9%) were women.

Overall learning style preferences.

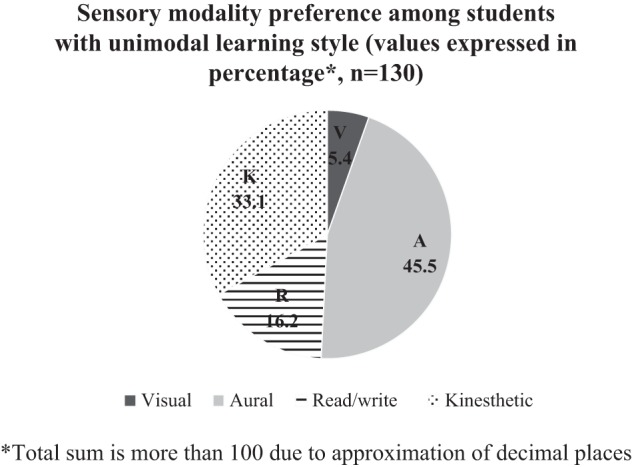

One hundred thirty students (31.3%) showed a unimodal learning style preference. Among the unimodal group, 45.5% of the students were auditory learners and 33.1% were kinesthetic learners. Preferred sensory modalities among unimodal learners are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sensory modality preferences among students with a unimodal learning style, as assessed by the visual-aural-read/write-kinesthetic (VARK) questionnaire. Values are expressed as percentages.

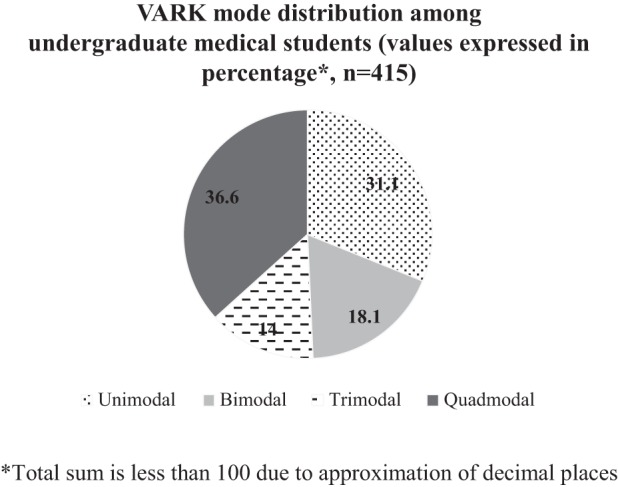

The majority of students (68.7%) preferred more than one sensory modality for learning. The percentages of students who preferred two, three, and four sensory modalities of learning are shown in Fig. 2. The most common VARK mode distribution among students was quadmodal (36.6%) followed by unimodal (31.3%), bimodal (18.1%), and trimodal (14%). The preferred combinations of sensory modalities among the bimodal and trimodal groups are shown in Table 1. Among the quadmodal group, the commonest VARK style based on the scores obtained for individual sensory modalities was kinesthetic-aural-reading/writing-visual learning (12.5%).

Fig. 2.

VARK mode distribution among undergraduate medical students. Values are expressed as percentages.

Table 1.

VARK mode distribution among bimodal and trimodal groups

| Bimodal Group |

Trimodal Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARK style | Number of students (n = 75 total) | Percentage | VARK style | Number of students (n = 58 total) | Percentage |

| AK | 23 | 30.7 | AKR | 6 | 10.3 |

| AR | 13 | 17.3 | AKV | 5 | 8.6 |

| AV | 2 | 2.7 | ARK | 12 | 20.7 |

| KA | 12 | 16 | ARV | 1 | 1.7 |

| KR | 5 | 6.7 | AVK | 2 | 3.4 |

| RA | 3 | 4 | AVR | 2 | 3.4 |

| RK | 7 | 9.3 | KAR | 6 | 10.3 |

| RV | 2 | 2.7 | KAV | 5 | 8.6 |

| VA | 4 | 5.3 | KRA | 3 | 5.2 |

| VK | 2 | 2.7 | KVA | 3 | 5.2 |

| VR | 2 | 2.7 | RAK | 4 | 6.9 |

| RKA | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| VAK | 3 | 5.2 | |||

| VKA | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| VKR | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| VRK | 3 | 5.2 | |||

V, visual; A, aural; R, reading/writing; K, kinesthetic.

Mean VARK scores for individual sensory modalities of learning are shown in Table 2. The mean score was highest for aural learning (7.11 ± 2.72) and lowest for visual learning (4.64 ± 2.48).

Table 2.

Mean scores of individual VARK components

| VARK Component | Mean Score | SD |

|---|---|---|

| V | 4.64 | 2.48 |

| A | 7.11 | 2.72 |

| R | 5.59 | 3.18 |

| K | 6.94 | 4.15 |

Sex and VARK.

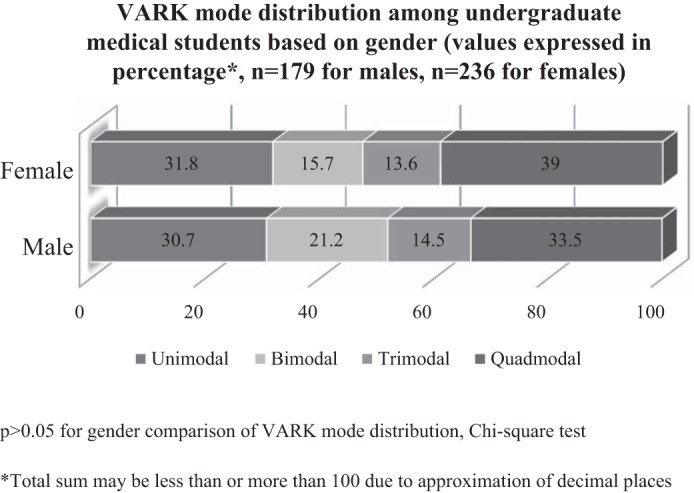

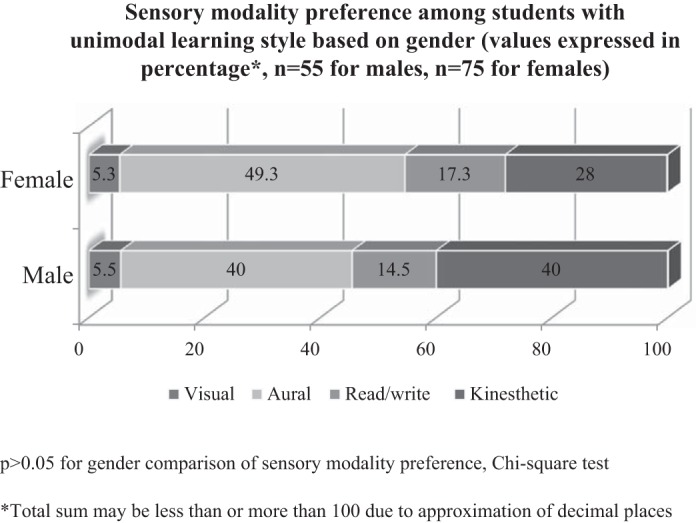

No significant sex difference was seen in terms of unimodal or multimodal learning preferences (Fig. 3). There was also no difference in individual sensory modality preference among unimodal learners (Fig. 4). Mean VARK scores for individual sensory modalities were also not significantly different (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

VARK mode distribution among undergraduate medical students based on sex. Values are expressed as percentages.

Fig. 4.

Sensory modality preferences among students with a unimodal learning style based on sex. Values are expressed as percentages.

Table 3.

Mean scores of individual VARK components based on sex

| VARK Component | Mean Score* | SD |

|---|---|---|

| V | ||

| Men | 4.59 | 2.41 |

| Women | 4.68 | 2.54 |

| A | ||

| Men | 7.17 | 2.92 |

| Women | 7.06 | 2.57 |

| R | ||

| Men | 5.40 | 3.96 |

| Women | 5.72 | 2.43 |

| K | ||

| Men | 7.21 | 5.69 |

| Women | 6.74 | 2.39 |

P > 0.05 for sex comparison in all groups by an independent samples t-test.

Academic performance and VARK.

Self-reported marks obtained in the 10th and 12th grades as well as last university examination were combined, and mean marks were divided into four categories (≤60%, >60% to ≤70%, >70% to ≤80%, and >80%). These were compared with individual VARK styles to determine the influence of academic performance on preference for a particular learning style. Comparison of the academic performance grade to individual sensory modality preference did not show any correlation. Table 4 shows mean scores of individual VARK components based on academic performance.

Table 4.

Mean scores of individual VARK components based on academic performance

| VARK Component* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance, % | V | A | R | K |

| ≤60 | 5.33 ± 3.21 | 4.67 ± 3.51 | 5.00 ± 2.65 | 4.00 ± 3.00 |

| >60 to ≤70 | 5.00 ± 2.58 | 6.59 ± 2.73 | 5.00 ± 2.61 | 6.08 ± 2.13 |

| >70 to ≤80 | 4.33 ± 2.51 | 7.26 ± 2.72 | 5.61 ± 2.70 | 7.47 ± 6.25 |

| >80 | 4.78 ± 2.45 | 7.10 ± 2.72 | 5.64 ± 3.49 | 6.76 ± 2.32 |

Values are means ± SD.

P > 0.05 for comparison of sensory modality of learning and academic performance by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey's post hoc test.

Perceived sensory modality and VARK.

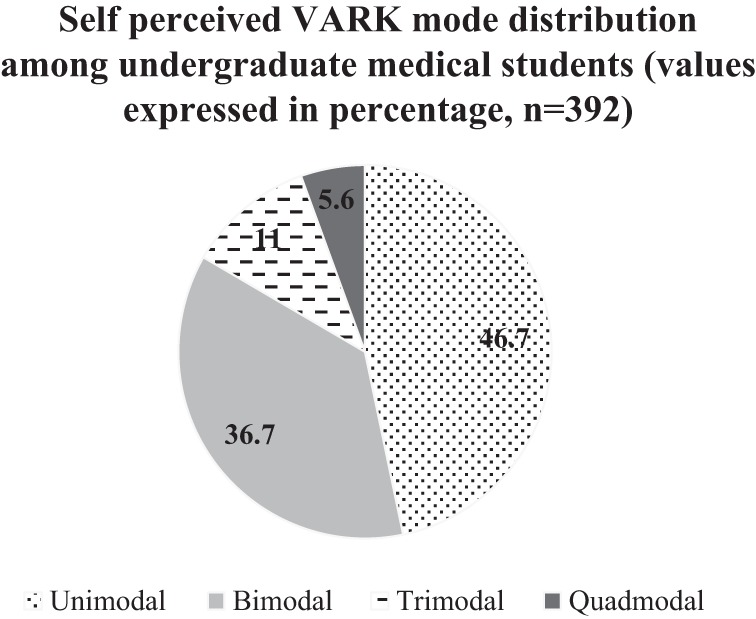

The majority of the students considered themselves to be unimodal (44.1%) or bimodal (34.7%) learners (Fig. 5). Twenty-three students did not indicate their VARK mode preference. Thus, Fig. 5 shows data from 392 students. Contrary to the assessed VARK style, self-perceived learning styles of students were reading/writing (42.1%) followed by visual (30.1%). Kinesthetic and aural learning styles constituted 15.8% and 12%, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Self-perceived VARK mode distribution among undergraduate medical students. Values are expressed as percentages.

DISCUSSION

Our study used the VARK questionnaire to determine the learning preferences of undergraduate medical students and the influence of sex and academic performance on learning styles. The majority of the students in our study had multiple learning preferences (68.7%). Similar results have been reported by authors from different geographic locations (2, 9, 11). The predominant sensory modality of learning among unimodal learners was aural (45.5%) followed by kinesthetic (33.1%). The same was reflected by mean scores for the various VARK components. Contrary to the assessed learning preference, the self-perceived preference was predominantly unimodal and bimodal (46.7% and 36.7%, respectively). This highlights the self-utility of the VARK questionnaire. Students can understand their own learning preferences, which can be contrary to their own perception. This helps them to actively engage in a learning environment that they would have otherwise perceived to be unsuitable.

Teaching in pharmacology in our institution predominantly consists of lecture classes using PowerPoint presentations and, to some extent, chalkboard teaching. Practical classes are predominantly small-group teaching/demonstrations. Those who predominantly are kinesthetic learners are least targeted in our current teaching methods. Also important is the fact that kinesthetic learning was an important component in the majority of the multimodal learners (Table 1). Moreover, mere presentation of a PowerPoint slide might not stimulate the visual learners unless the slide content is organized in a manner that it can be read and understood during the limited time it is projected even if the student was not listening to the lecture. The same is true for the other sensory modalities. Multimodal learning does help at least to some extent in overcoming some of the deficiencies.

The influence of sex on learning styles is an area of active research. Previous studies have not yielded any uniform results in that the learning preference of female students has ranged from being predominantly unimodal to predominantly multimodal (3, 13, 14). In our study, most of the female undergraduate medical students (68.3%) preferred more than one modality of learning. Among those with unimodal preferences, female students were predominantly aural (49.3%), whereas an equal number of male students preferred aural and kinesthetic (40%). Unlike a previous study (13) that showed that among students with multimodal learning preferences female students had a more diverse combination of sensory modalities, our study showed diverse sensory modality combinations in both sexes. Hence, in our study sample, sex did not significantly influence the learning style preference. Considering the differing results from various studies, no generalizations can be made regarding the influence of sex.

Our study also assessed the influence of academic performance on learning style preference. No correlation was found between the academic performance of students and their preferred VARK style. Few previous studies have addressed the same issue. No definite conclusions can be drawn from these studies. A study among nurses showed a correlation between good performance and multimodal learning (1). However, a similar study among dental students showed no statistical association (2). Two studies among physiology students showed a relatively poor performance by students who preferred the kinesthetic modality (3, 4). Similar to the influence of sex, no generalized conclusions could be drawn with regard to the influence of academic performance. The VARK questionnaire does not provide for a complete assessment of learning style, nor was it intended to. Learning is influenced by multiple components, such as psychological, social, physical, and environmental elements (5). For example, nurses and lawyers require different skill sets, which would influence their learning style, including adopting or getting used to a learning style that one may not be comfortable with at the beginning (13). Similarly, translating the effects of an improved teaching method that caters to all types of learners into improved academic performance or learning has been difficult to demonstrate considering the lack of a definition for learning and methods to measure it (6).

Our study has limitations. The academic performance data was based on self-reported marks obtained in the various examinations. This could have led to recall bias or inaccurate reporting. Our study does not address whether altering the teaching methods according to student learning styles improves academic performance. It only tells us that differing past academic performance did not significantly influence the learning style preference of students. Although our study showed no influence of sex on learning style preferences, a larger study sample might have shown a statistically significant difference considering that our study sample showed more kinesthetic learners among men, which was not statistically significant (40% vs. 28% for men vs. women, respectively). While collecting data on self-perceived learning style preferences, students were allowed to select multiple preferences. Hence, we were unable to determine the self-perceived dominant learning modality.

In conclusion, our study was an attempt to describe the learning styles of undergraduate medical students in our institution. Based on the questions raised by previous studies, we also studied the influence of sex and previous academic performance on learning style preference. Most of the students were multimodal learners, which is good from both a teaching as well as learning perspective. Aural and kinesthetic were the preferred sensory modalities of learning. Neither sex nor previous academic performance had any relation to learning style preference. Although we use a combination of teaching methods, there has not been an active effort to determine whether these adequately address the different types of learners. We hope these data will help us better our course contents and make learning a more fruitful experience.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.P.U., S.U., A.K.S., N.S., and L.A.U. conception and design of research; R.P.U. and S.U. performed experiments; R.P.U. and A.K. analyzed data; R.P.U. and A.K. interpreted results of experiments; R.P.U., A.K., S.U., A.K.S., N.S., and L.A.U. edited and revised manuscript; R.P.U., S.U., A.K.S., N.S., and L.A.U. approved final version of manuscript; A.K. prepared figures; A.K. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Neil D. Fleming for permission to use the VARK questionnaire [copyright version 7.0 (2006) held by Neil D. Fleming, Christchurch, New Zealand, and Charles C. Bonwell, Green Mountain Falls, CO 80819].

REFERENCES

- 1. Alkhasawneh IM, Mrayyan MT, Docherty C, Alashram S, Yousef HY. Problem-based learning (PBL): assessing students' learning preferences using VARK. Nurs Educ Today 28: 572–579, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baykan Z, Nacar M. Learning styles of first-year medical students attending Erciyes University in Kayseri, Turkey. Adv Physiol Educ 31: 158–160, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dobson JL. A comparison between learning style preferences and sex, status and course performance. Adv Physiol Educ 34: 197–204, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dobson JL. Learning style preferences and course performance in an undergraduate physiology class. Adv Physiol Educ 33: 308–314, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felder RM, Brent R. Understanding student differences. J Eng Educ 94: 57–72, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fleming ND. The Case Against Learning Styles: “There Is No Evidence . . .” (online). http://www.vark-learn.com/documents/The%20Case%20Against%20Learning%20Styles.pdf (1 May 2014).

- 7. Fleming ND, Mills C. Not Another Inventory, Rather a Catalyst for Reflection (online). http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1245&context=podimproveacad (1 May 2014).

- 8. Fleming ND. VARK: a Guide to Learning Styles (online). http://www.vark-learn.com (1 May 2014).

- 9. Lujan H, DiCarlo S. First-year medical students prefer multiple learning styles. Adv Physiol Educ 30: 13–16, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medical Council of India. Medical Council of India Regulations on Graduate Medical Education, 1997 (online). http://www.mciindia.org/Rules-and-Regulation/GME_REGULATIONS.pdf (1 May 2014).

- 11. Nuzhat A, Salem RO, Quadri MSA, Al-Hamdan N. Learning style preferences of medical students: a single-institute experience from Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Educ 2: 70–73, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slater JA, Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. Does gender influence learning style preferences of first-year medical students? Adv Physiol Educ 31: 336–342, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Academic Learning Centre, University of Manitoba. Learning Styles (online). https://umanitoba.ca/student/academiclearning/media/Learning_Styles_NEW.pdf [1 May 2014].

- 14. Wehrwein EA, Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. Gender differences in learning style preferences among undergraduate physiology students. Adv Physiol Educ 31: 153–157, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]