Abstract

We have investigated the effect of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) on the production of extracellular matrix-degrading proteases in skeletal muscles. Using microarray, quantitative PCR, Western blotting, and zymography, we found that TNF-α drastically increases the production of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 from C2C12 myotubes. In vivo administration of TNF-α in mice increased the transcript level of MMP-9 in skeletal muscle tissues. Although TNF-α activated all the three MAPKs (i.e. ERK1/2, JNK, and p38), inhibition of ERK1/2 or p38 but not JNK blunted the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 from myotubes. Inhibition of Akt also inhibited the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9. TNF-α increased the activation of transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 but not SP-1 in myotubes. Overexpression of a dominant negative inhibitor of NF-κB or AP-1 blocked the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in myotubes. Similarly, point mutations in AP-1- or NF-κB-binding sites in MMP-9 promoter inhibited the TNF-α-induced expression of a reporter gene. TNF-α increased the activity of transforming growth factor-β-activating kinase-1 (TAK1). Furthermore, overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of TAK1 blocked the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 and activation of NF-κB and AP-1. Our results also suggest that TNF-α induces MMP-9 expression in muscle cells through the recruitment of TRAF-2, Fas-associated protein with death domain, and TNF receptor-associated protein with death domain but not NIK or TRAF-6 proteins. We conclude that TAK1-mediated pathways are involved in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 production in skeletal muscle cells.

Skeletal muscle wasting or atrophy is a debilitating complication of several conditions, including immobilization, zero gravity space travel, and many chronic diseases such as cancer, heart failure, diabetes, AIDS, and sepsis (1,2). In vivo, skeletal muscle fibers are surrounded by a layer of extracellular matrix (ECM)2 material called the basement membrane, which is composed of an internal basal lamina directly linked to sarcolemma and an external fibrillar lamina (3). The main components of basal lamina are type IV collagen, laminin, and proteoglycans rich in heparin sulfate. Genetic studies of muscular dystrophy patients and animal models of muscular dystrophy have provided strong evidence that the components of ECM are critical for maintaining structure and normal function of skeletal muscle (4-7). ECM is not only required to maintain tensile strength and elasticity in skeletal muscle tissues, it is also important for the assembly of neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions and for the regeneration of myofibers after injury or excessive exercise (3). Thus, the degradation of ECM would result in structural and functional deterioration and loss of skeletal muscle fibers.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of calcium- and zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes that function mainly in the extracellular matrix (8). Genetic and pharmacological studies have provided compelling evidence that although MMPs are required for normal development and functioning, excessive production of MMPs leads to pathology of a wide range of tissues (9). Accumulating evidence suggests that increased expression of MMPs could lead to loss of skeletal muscle mass in different physiological and pathophysiological conditions (10). Increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 has been reported in the atrophic soleus and gastrocnemius muscles with a concomitant decrease in the levels of collagen I and collagen IV, two major ECM components present in skeletal muscle (11,12). MMP-2 and MMP-9 are strongly up-regulated in experimental ischemia/reperfusion injury leading to degradation of basal lamina in skeletal muscle (13). Furthermore, increased expression of MMPs has also been reported in atrophying skeletal muscle after nerve injury (14), heart failure (15,16), and in the pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies (17-19).

Several lines of evidence suggest that TNF-α plays a major role in the development of muscular abnormalities resulting in a loss of skeletal muscle mass and function (20). Increased levels of TNF-α have been observed under conditions that lead to skeletal muscle atrophy such as cachexia induced by bacteria, human immunodeficiency virus, chronic heart failure, and cancer (21). TNF-α transduces its biological activities by binding to two 55- and 75-kDa receptors (22,23). Trimeric occupation of TNF receptors by the ligand results in the recruitment of receptor-specific proteins and promotes the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and AP-1 (activator protein-1) through activation of a cascade of upstream kinases, including IκB kinase (IKK), the MAPKs, and Akt (22,24). Recent reports also suggest that transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase1 (TAK1), a member of the MAP3K family, is critical for TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, especially p38 (25-27). Although the precise role of various signaling proteins and transcription factors in TNF-α-induced skeletal muscle atrophy remains to be established, some of these molecules may serve as important molecular targets for the prevention of skeletal muscle loss in future therapies. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the inhibition of NF-κB, a transcription factor that is also activated by TNF-α, can prevent skeletal muscle loss in conditions known to exacerbate muscle-wasting (28-30).

We hypothesize that one of the mechanisms by which TNF-α can induce loss of skeletal muscle mass and function is through augmenting the production of ECM-degrading enzymes from skeletal muscle cells. To test this hypothesis, we have performed a genome-wide microarray analysis using RNA isolated from control and TNF-α-treated cultured C2C12 myotubes. Among others, we have identified MMP-9, a type IV collagenase, as one of the highly up-regulated ECM proteases in TNF-α-treated C2C12 myotubes. In this study, for the first time we demonstrate that TNF-α causes spurious expression and production of MMP-9 from skeletal muscle cells both in vitro and in vivo. We have also delineated the molecular pathways that lead to enhanced expression of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes in response to TNF-α treatment. Our data suggest that TAK1, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, NF-κB, and AP-1 transcription factors constitute the biochemical signaling pathway(s) that leads to the enhanced production of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes in response to TNF-α.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum were obtained from Invitrogen. Horse serum was purchased from Sigma. LY294002, wortmannin, PD98059, SP600125, and SB203580 were obtained from Calbiochem. Poly(dI·dC) was from GE Healthcare. [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity, 3000 (111 TBq) Ci/mmol) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Protein A-Sepharose beads were obtained from Pierce. Recombinant mouse TNF-α protein was from BioVision (Mountain View, CA). Effectene transfection reagent was obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). NF-κB consensus oligonucleotides and luciferase assay kits were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Phospho-specific rabbit polyclonal anti-p44/42 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), anti-p38 (Thr-180/Tyr-182), anti-Akt (Ser-473), anti-IκBα (Ser-32), and anti-TAK1 (Ser-412) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against JNK1, p50, p65, c-Rel, Bcl3, TAK1, and c-Jun proteins and AP-1 and SP-1 consensus oligonucleotides were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against mouse MMP-9 and MMP-2 proteins were obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Mice

C57BL6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed and fed in stainless steel cages on a 10-h on and 14-h off lighting schedule. Prior approval was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jerry L. Pettis Memorial VA Medical Center, Loma Linda, CA, for conducting experiments with mice. All procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the Public Health Service and Department of Veterans Affair animal welfare policy.

Cell Culture

C2C12 and L6 myoblastic cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). These cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. C2C12 myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in differentiation medium (DM, 2% horse serum in DMEM) for 96h as described (31,32). Myotubes were maintained in DM, and medium was changed every 48 h. L6 myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in 0.5% fetal bovine serum for 48–72 h.

Plasmid Constructs

Full-length mouse c-Jun was isolated from cDNA made from C2C12 myoblasts. Briefly, total RNA was isolated, and first strand cDNA was generated using oligo(dT) primer (from Ambion) and OmniScript reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). c-Jun construct was prepared by amplifying the murine c-Jun cDNA (GenBank™ accession number NM_010591) with the following primers: sense 5′-CGT TCT ATG ACT GCA AAG ATG G-3′ (c-Jun forward), and antisense, 5′-CAG CCC TGA CAG TCT GTT CT-3′ (c-Jun reverse). A dominant negative mutant of c-Jun, called TAM-67 (33), was generated by removal of the transactivational domain (amino acids 3–122) of wild-type c-Jun by PCR using the following primers: sense 5′-ATG ACT AGC CAG AAC ACG CTT CCC A-3′ (TAM67 forward) and antisense, 5′-CAG CCC TGA CAG TCT GTT CT-3′ (c-Jun reverse). All PCR amplifications were performed using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). PCR products were cloned into pCR®Blunt II TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and the authenticity of cDNA was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing. Finally, c-Jun or TAM67 cDNA was excised from pCR®Blunt II TOPO vector using HindIII and XbaI restriction enzymes and inserted into pcDNA3 plasmid (Invitrogen) at HindIII and XbaI sites. The expression of proteins from plasmid constructs was confirmed using T7 based on the in vitro translation kit (Promega).

The pcDNA3-FLAG-IκBαΔN plasmid has been described in one of our recent publications (34). Plasmid constructs encoding murine wild-type HA-TAK1 or a dominant negative mutant (HA-TAK1K63W) and His-MKK6 as described (35) were kindly provided by Dr. Jun Ninomiya-Tsuji, North Carolina State University. The 0.67-kb fragment of the MMP-9 promoter construct, together with two deletions (-599 and -73) and three mutation constructs (AP-1 mutant, TGAGTCA to TTTGTCA; NF-κB mutant, GGAATTCCCC to TTAATTCCCC; Sp-1 mutant, CCGCCC to CCAACC) ligated to the firefly luciferase reporter gene (36) were a gift from Dr. ShouWei Han, of Emory University School of Medicine. Dominant negative constructs for TRADD, FADD, TRAF2, TRAF6, and NIK were kindly provided by Prof. Bharat B. Aggarwal of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. pTAL-SEAP and pNF-κB-SEAP plasmids were purchased from Clontech.

Transient Transfection and Reporter Assays

C2C12 myoblasts plated in either 6-well or 24-well tissue culture plates were transfected with different plasmids using Effectene transfection reagent according to the protocol suggested by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Transfection efficiency was controlled by cotransfection of myoblasts with pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid. When >90% confluent, the cells were differentiated by changing medium to DM. After appropriate treatments, specimens were processed for luciferase and β-galactosidase expression using the luciferase and β-galactosidase assay systems with reporter lysis buffer per the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase measurements were made using a luminometer (model 3010, Analytic Scientific Instrumentation). Alkaline phosphatase activity in culture supernatants was measured by a standard assay using para-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate.

Gelatin Zymography

C2C12 myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in DM for 96 h. Myotubes were treated with TNF-α for 14 h in serum-free medium, and the conditioned medium collected was subjected to gelatin zymography as described (37). Unconditioned medium was used as a negative control. In brief, conditioned media samples were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg/ml gelatin B (Fisher) under nonreducing conditions. Gels were washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation in reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, and 0.02% sodium azide) for 16 h at 37 °C. To visualize gelatinolytic bands, gels were stained with Coomassie Blue at room temperature followed by extensive washing in destaining buffer (10% methanol and 10% acetic acid in distilled water). The gels were dried and scanned under a densitometer for determination of gelatinolytic activity.

Kinase Assays

The detailed protocol for assaying the JNK1 and IKK has been described previously (31,38). For measuring the TAK1 activity, 800 μg of protein was immunoprecipitated using rabbit polyclonal TAK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and the immune complex was collected using protein A-Sepharose beads. After washing two times with lysis buffer and two times with kinase buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol), the beads were suspended in 20 μl of kinase assay mixture containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 20 mm MgCl2, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, 1 μm unlabeled ATP, and 2 μg of His-MKK6 as substrate. After incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, the reaction was terminated by boiling with 20 μl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer for 3 min. Finally, the protein was resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gel; the gel was dried, and the radioactive bands were visualized by exposing to a PhosphorImager screen and quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Western Blotting

Western blot was performed to measure the levels of different proteins using a standard protocol as described previously (32,39). The dilution for all the primary antibodies was 1:100.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The activation of NF-κB, AP-1, and SP-1 transcription factors was measured by EMSA. The detailed method for preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts and EMSA has been described in detail in our recent publications (31,40).

Gene Expression Analysis Using Microarray Techniques

Total RNA was isolated from C2C12 myotubes 18 h after TNF-α treatment, using the Agilent total RNA isolation kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Each experiment was performed with a minimum of five replicates. The total RNA concentration was determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and RNA quality was determined by 18 S/28 S ribosomal peak intensity on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. For microarray expression profiling and real time PCR, RNA samples were used only if they showed little to no degradation. Custom cDNA slides were spotted with Oligator “MEEBO” mouse genome set with 38,467 cDNA probes (Illumina, Inc., San Diego), which allows interrogation of 25,000 genes. A Q-Array2 robot (Genetix) was used for spotting. The array includes positive controls, doped sequences, and random sequence to ensure correct gene expression values were obtained from each array. A total of 250 ng of RNA was used to synthesize double-stranded cDNA using the low RNA input fluorescent linear application kit (Agilent). The microarray slides were scanned using a GSI Lumonics ScanArray 4200A Genepix scanner (Axon). The image intensities were analyzed using the ImaGene 5.6 software (Biodiscovery, Inc., El Segundo, CA). Expression analysis of microarray experiments was performed with GeneSpring 7.1 (Silicon Genetics, Palo Alto, CA) using the raw intensity data generated by the ImaGene software. Local background-subtracted total signal intensities were used as intensity measures, and the data were normalized using per spot and per chip LOWESS normalization. The changes in transcript levels were analyzed utilizing a t test with Benjamini and Hochberg Multiple Testing Correction.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real Time-PCR

RNA isolation and QRT-PCR was performed to measure the mRNA level of different MMPs and TIMPs following a method described recently (31,32). The sequence of the primers was as follows: MMP-2, 5′-ACA GCC AGA GAC CTC AGG GT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAG CAC AGG ACG CAG AGA AC-3′ (reverse); MMP-9, 5′-GCG TGT CTG GAG ATT CGA CTT G-3′ (forward) and CAT GGT CCA CCT TGT TCA CCT C (reverse); MMP-14, 5′-ATT TGC TGA GGG TTT CCA CG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCG GCA GAA TCA AAG TGG GT-3′ (reverse); TIMP-1, 5′-TTG CAT CTC TGG CAT CTG GCA T-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAT ATC TGC GGC ATT TCC CAC A-3′ (reverse); TIMP-2, 5′-GTGACTTCATTGTGCCCTGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGG GAC AGC GAG TGA TCT TGC-3′ (reverse); and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 5′-ATG ACA ATG AAT ACG GCT ACA GCA A-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCA GCG AAC TTT ATT GAT GGT ATT-3′ (reverse). Data normalization was accomplished using the endogenous control gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and the normalized values were subjected to a 2-ΔΔCt formula to calculate the fold change between the control and experiment groups. The formula and its derivations were obtained from the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system user guide.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. The Student's t test or analysis of variance was used to compare quantitative data populations with normal distributions and equal variance. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Results

Here we have investigated the effects of TNF-α on the expression of ECM-degrading proteases, especially MMPs in C2C12 myotubes. We have also delineated the molecular pathways that lead to increased expression of MMP-9 in response to TNF-α in C2C12 myotubes. The concentrations of TNF-α and various pharmacological inhibitors used in this study are within physiological range and have been widely used in different cell types, including skeletal muscle.

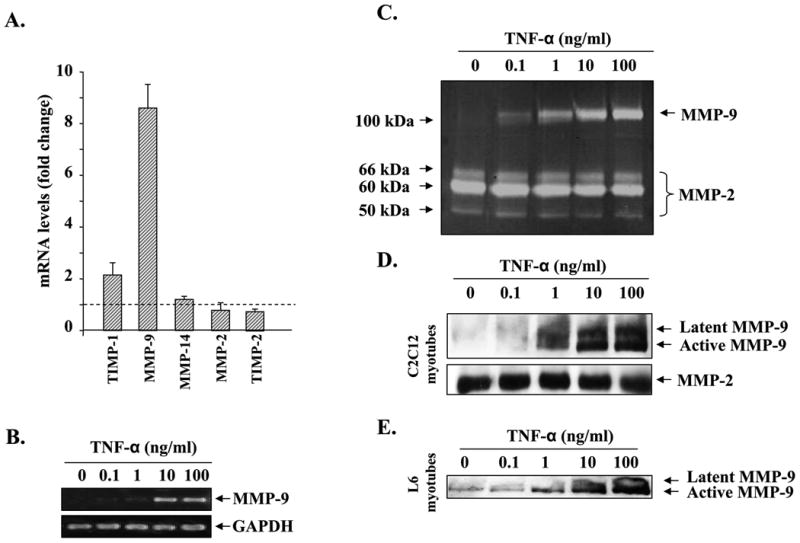

TNF-α Modulates the Expression of MMPs and Their Inhibitors in Cultured Myotubes

We employed a microarray approach to determine how TNF-α affects the expression of various MMPs and their inhibitors in cultured C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in differentiation medium for 96 h. The myotubes were then treated with recombinant mouse TNF-α protein (10 ng/ml) for 18 h. The total RNA isolated from control or TNF-α-treated myotubes was subjected to microarray analysis for the expression of MMP family genes. Interestingly, among 40 genes of the MMP family present in our microarray slides (supplemental Table 1S), the expression of only a few MMPs and TIMPs was significantly altered in TNF-treated myotubes compared with controls (Table 1). In particular, the expression of MMP-9, MMP-14, and TIMP-1 was significantly increased, whereas the expression of TIMP-2 and MMP-2 was reduced.

Table 1.

List of matrix metalloproteinase-related genes significantly affected in TNF-treated myotubes.

| Gene Name | Fold Change | p-value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timp1 | 1.6 | < 0.001 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 |

| Mmp9 | 1.5 | 0.006 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| Mmp14 | 1.1 | 0.010 | Matrix metalloproteinase 14 |

| Mmp2 | 0.9 | 0.003 | Matrix metalloproteinase 2 |

| Timp2 | 0.8 | 0.027 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 |

To validate the microarray data for the expression of MMPs and TIMPs, we performed QRT-PCR using their specific primers and RNA samples used in the microarray experiments. Interestingly, the mRNA level of MMP-9 was found to be drastically higher (>8-fold) in TNF-α-treated myotubes compared with untreated control myotubes (Fig. 1A). Indeed, in several other independent experiments, we found that the mRNA level of MMP-9 was increased up to 50-fold within 24 h of treatment of myotubes with TNF-α (data not shown). On the other hand, the increase in the mRNA level of TIMP-1, an inhibitor of MMP-9, was only ∼2-fold in QRT-PCR (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, QRT-PCR analysis also confirmed that the changes in the mRNA levels of MMP-2, MMP-14, and TIMP-2 were significant but not drastic (Fig. 1A). These data provide the first evidence that TNF-α can affect the expression of various MMP-related genes in C2C12 myotubes.

Fig. 1. TNF-α modulates the expression of MMPs and TIMPs in skeletal muscle cells.

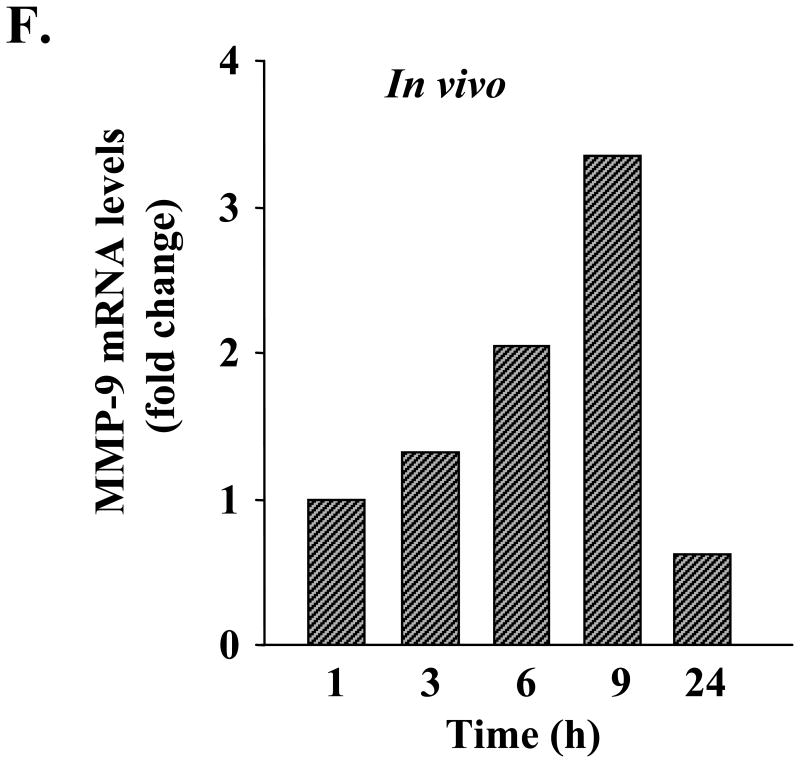

A, RNA samples (same as used in microarray experiments) from control and TNF-α-treated C2C12 myotubes were subjected to quantitative real time PCR for the expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2. Data presented here show that TNF-α drastically increases the expression of MMP-9 in myotubes. B, C2C12 myotubes were treated with increasing concentrations of TNF-α for 14 h, and the expression of MMP-9 was studied by the semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR method. Data presented here show that TNF-α augments the expression of MMP-9 in myotubes in a dose-dependent manner. C, culture supernatants from TNF-α-treated myotubes were analyzed for the production of MMP-9 using gelatin zymography. Data presented here demonstrate that TNF-α augments the secretion of MMP-9 in culture supernatants without affecting the production of MMP-2. D, culture supernatants of TNF-α-treated C2C12 myotubes were subjected to Western blot analysis for MMP-9 and MMP-2 proteins. A representative immunoblot presented here shows that TNF-α increases the amount of MMP-9 protein in culture supernatants in a dose-dependent manner without affecting MMP-2 levels. E, L6 myotubes were treated with different concentrations of TNF-α protein, and the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants was measured by Western blotting. Data presented here show that TNF-α augments the production of MMP-9 in L6 myotubes as well. F, 6-week-old C57BL6 mice were given intraperitoneal injections of recombinant TNF-α protein (100 ng/g body weight), and the expression of Mmp-9 in gastrocnemius muscle at different time intervals was studied by QRT-PCR. Data presented here show that in vivo administration of TNF-α increases the expression of MMP-9 in muscle tissues.

TNF-α Augments the Production of MMP-9 in Skeletal Muscle Cells Both in Vitro and in Vivo

Because MMP-9 is one of the major ECM-degrading enzymes (8) and its transcript level was increased on treatment of myotubes with TNF-α, we investigated whether the increased expression of MMP-9 was associated with increased secretion of MMP-9 in culture supernatants. C2C12 myotubes were incubated in serum-free medium with increasing amounts of TNF-α for 14 h, and the expression of MMP-9 was studied by semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, and the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants was measured by zymography. Treatment of myotubes with TNF-α increased the mRNA levels of MMP-9 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Analysis of culture supernatants by gelatin zymography showed that the increased expression of MMP-9 was associated with increased production of MMP-9 protein in culture supernatants (Fig. 1C). Western blot analysis of culture supernatants of C2C12 myotubes showed that there was a drastic increase in the levels of MMP-9 protein on treatment with TNF-α. Interestingly, Western blot analysis also showed that culture supernatants from TNF-treated myotubes contain predominantly the active form of MMP-9 protein (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, by performing immunohistochemistry in control and TNF-α-treated myotubes using MMP-9 antibody, we confirmed that MMP-9 was produced mainly by myotubes and not by a few undifferentiated myoblasts that were present in C2C12 cultures even after 96 h of incubation in DM (supplemental Fig. 1S).

To understand if the increased production of MMP-9 in response to TNF-α was specific to C2C12 myotubes or other types of skeletal muscle cells also respond similarly to TNF-α with respect to MMP-9 production, we investigated the effect of TNF-α on the production of MMP-9 in L6 myotubes. As shown in Fig. 1E, treatment of L6 myotubes with TNF-α increased the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants in a dose-dependent manner. In another experiment, we also investigated whether TNF-α can induce Mmp-9 gene expression in vivo. Six-week-old mice were given a single intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α protein (100 ng/g body weight), and the expression of MMP-9 in gastrocnemius muscle was studied by QRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1F, in vivo administration of TNF-α increased the transcript level of MMP-9 (maximally at 9 h) in skeletal muscle tissues. Collectively, these data suggest that TNF-α augments the expression and secretion of MMP-9 from muscle cells and tissues.

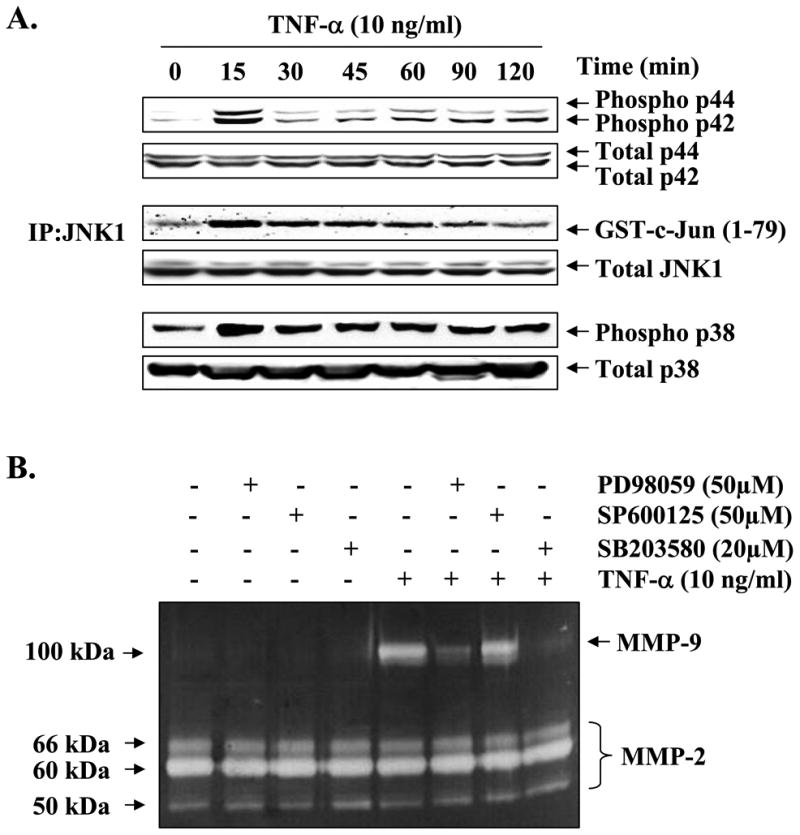

ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK Are Involved in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 Production in Myotubes

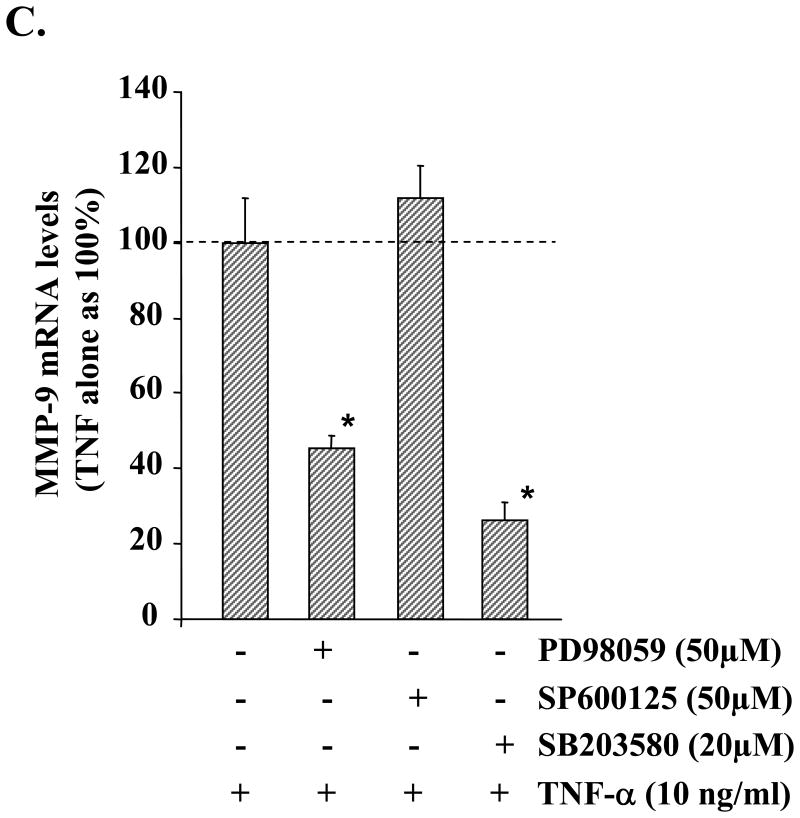

To understand the molecular pathways that lead to increased expression/production of MMP-9 in muscle cells in response to TNF-α, we investigated the role of MAPKs. C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α for different time intervals ranging from 0 to 120 min. The activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK was studied by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies, and the activation of JNK1 was studied by immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay. Treatment of C2C12 myotubes with TNF-α led to a significant increase in the activation of ERK1/2, JNK1, and p38 MAPK (Fig. 2A). To understand if the activation of MAPKs in response to TNF-α was responsible for TNF-α-induced Mmp-9 gene expression, C2C12 myotubes were preincubated with PD98059 (MEK1/2 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK1 inhibitor), or SB203580 (p38 kinase inhibitor) followed by addition of TNF-α. The secretion of MMP-9 in culture supernatants was studied by gelatin zymography. As shown in Fig. 2B, pretreatment of C2C12 myotubes with PD98059 or SB203580 blocked the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants. Similarly, the mRNA level of MMP-9 in myotubes was also significantly reduced in the presence of PD98059 or SB203580 on treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, JNK inhibitor SP600125 did not have any significant effect on MMP-9 production in TNF-α-treated C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 2, B and C). These data indicate that TNF-α augments the production of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes through the activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK.

Fig. 2. Role of MAPK in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in skeletal muscle cells.

A, C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time intervals, and the activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK was studied by immunoblotting with phospho-ERK1/2 or phospho-p38 antibody. JNK1 activity was determined by immunoprecipitation (IP) with JNK1 antibody followed by in vitro kinase assay using GST-c-Jun-(1–79) as substrate. Representative data presented here show that TNF-α activates ERK1/2, JNK1, and p38 MAPK in myotubes. B, C2C12 myotubes were preincubated in serum-free medium with either PD98059 (50 μm), SP600125 (50 μm), or SB203580 (20 μm) for 2 h followed by addition of TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and incubation for additional 14 h. A representative gelatin zymography gel from three independent experiments presented here show that PD98059 and SB203580 inhibit the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants in response to TNF-α treatment. C, QRT-PCR analyses of the RNA samples isolated from PD98059, SP600125, or SB203580-treated myotubes showed that PD98059 and SB203580 inhibits the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in myotubes. *, p < 0.05, values significantly different from myotubes incubated in TNF-α alone. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

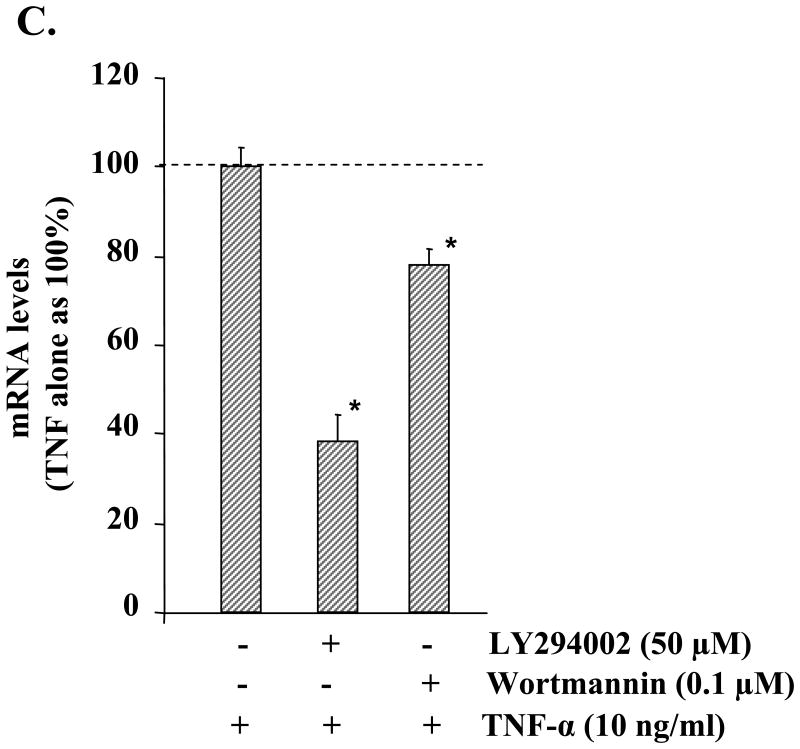

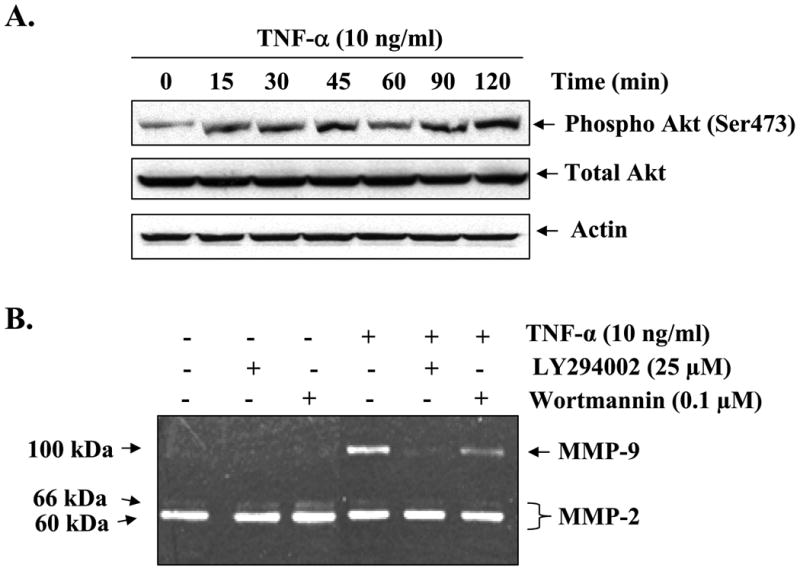

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Akt Are Involved in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 Production in C2C12 Myotubes

Accumulating evidence suggests that the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway contributes to the production of MMP-9 in some cell types under specific conditions (36). We investigated whether TNF-α can activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and if the activation of this pathway contributes to the increased production of MMP-9 in myotubes. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment of myotubes with TNF-α resulted in sustained activation of Akt, a central kinase of the PI3K/Akt pathway. To investigate the involvement of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9, we used LY294002 and wortmannin, pharmacological inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt pathway. As shown in Fig. 3B, pretreatment with LY294002 or wortmannin significantly inhibited the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants of TNF-α-treated myotubes. Consistent with the amounts of MMP-9 in culture supernatants, the transcript levels of MMP-9 were also found to be considerably lower in LY294002 or wortmannin-treated myotubes in response to TNF-α (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Involvement of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in C2C12 myotubes.

A, C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time intervals, and the activation of Akt was studied by immunoblotting with phospho-Akt (Ser-473) antibody. A representative immunoblot presented here shows that TNF-α augments the activation of Akt kinase in C2C12 myotubes without affecting the total cellular level of Akt or the unrelated protein actin. B, C2C12 myotubes were preincubated with either LY294002 (25 μm) or wortmannin (0.1 μm) for 2 h followed by treatment with TNF-α for an additional 14 h. Production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants was measured by gelatin zymography. Representative data from three independent experiments presented here show that both LY294002 and wortmannin inhibit the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants. C, measurement of mRNA levels by QRT-PCR showed that LY294002 or wortmannin inhibits the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in muscle cells. *, p < 0.05, values significantly different from myotubes incubated with TNF-α alone.

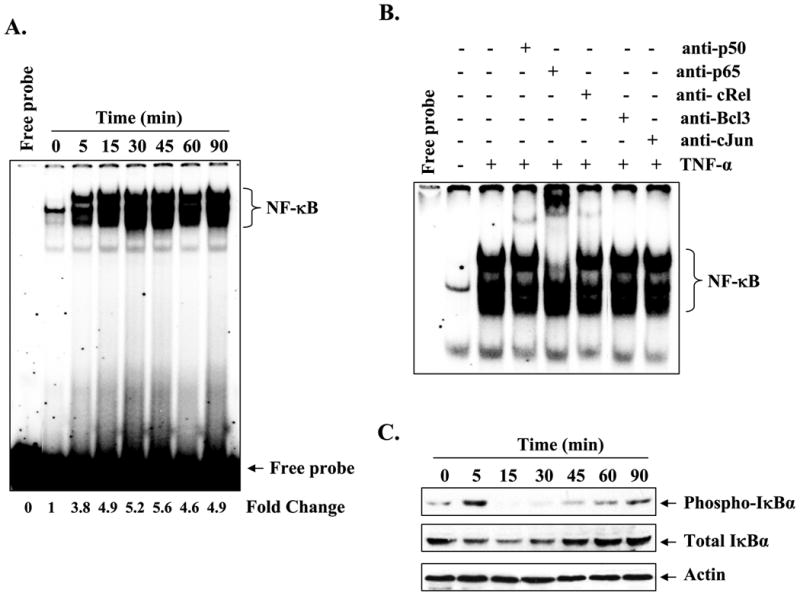

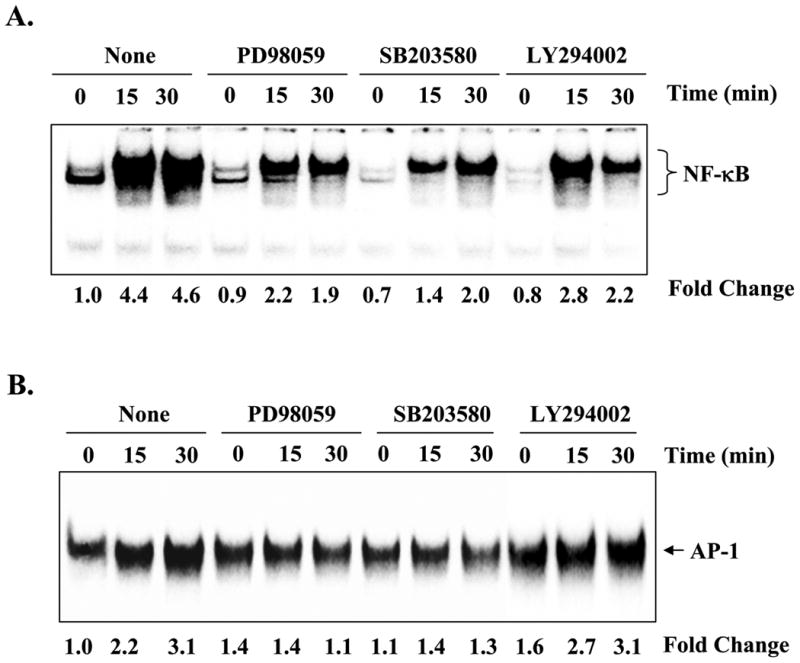

TNF-α Activates NF-κB and AP-1 Transcription Factors in Cultured Myotubes

Mmp-9 gene promoter contains consensus sequence for NF-κB, AP-1, and SP-1 transcription factors that are conserved in human and mouse (41,42). We first investigated whether TNF-α can cause the activation of NF-κB, AP-1, and SP-1 in myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α for different time intervals, and the activation of NF-κB was studied by EMSA. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment with TNF-α drastically increased the DNA binding activity of NF-κB in myotubes.

Fig. 4. TNF-α activates NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors in C2C12 myotubes.

A, C2C12 myotubes were incubated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time intervals, and the activation of NF-κB was measured by EMSA. A representative EMSA gel presented here shows that TNF-α activates NF-κB transcription factor in myotubes. B, supershift analysis of the NF-κB-DNA complex from 30-min treated myotubes showed that it contains mainly p50, p65, and c-Rel subunits of NF-κB. C, Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic extracts from TNF-α-treated myotubes revealed that increased activation of NF-κB was associated with the phosphorylation (upper panel) and degradation (middle panel) of the IκBα protein. The level of an unrelated actin protein did not change on treatment of myotubes with TNF-α (bottom panel). D, measurement of IKK activity in cytoplasmic extracts revealed that TNF-α augments the activation of IKK in myotubes (top panel). There was no effect on the cellular level of either IKKα (middle panel) or IKKβ (bottom panel) on treatment of myotubes with TNF-α. E, representative EMSA gels presented here show that TNF-α also increases the activation of the AP-1 transcription factor in myotubes without affecting the activation of the SP-1 transcription factor.

Because different combinations of Rel/NF-κB proteins can constitute an active NF-κB dimer that binds to specific sequences in DNA (43), we performed a supershift assay to determine which subunits of NF-κB are activated in response to TNF-α treatment. Incubation of nuclear extracts from TNF-α-treated myotubes with antibodies against p50, p65, and c-Rel proteins of NF-κB family shifted the band to higher levels of molecular weight, indicating that the NF-κB-DNA complex analyzed by EMSA constitutes these proteins (Fig. 4B).

Because in the canonical NF-κB pathway the activation of NF-κB generally precedes the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα (43), we also studied the effect of TNF-α on the phosphorylated and total IκBα protein levels in myotubes. As shown in Fig. 4C, treatment of myotubes with TNF-α augmented both phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα protein. Furthermore, the activation of IKK, an upstream activator of NF-κB pathway that phosphorylates IκBα protein (43), was also increased in C2C12 myotubes in response to TNF-α (Fig. 4D). Because Mmp-9 gene promoter also contains a binding site for AP-1 and SP-1 transcription factors, we also measured the activation of AP-1 and SP-1 in TNF-α-treated myotubes using EMSA. The DNA binding activity of AP-1 was enhanced in response to TNF-α treatment (Fig. 4E, upper panel). On the other hand, the activation of SP-1 was not affected in TNF-α-treated myotubes (Fig. 4E, lower panel).

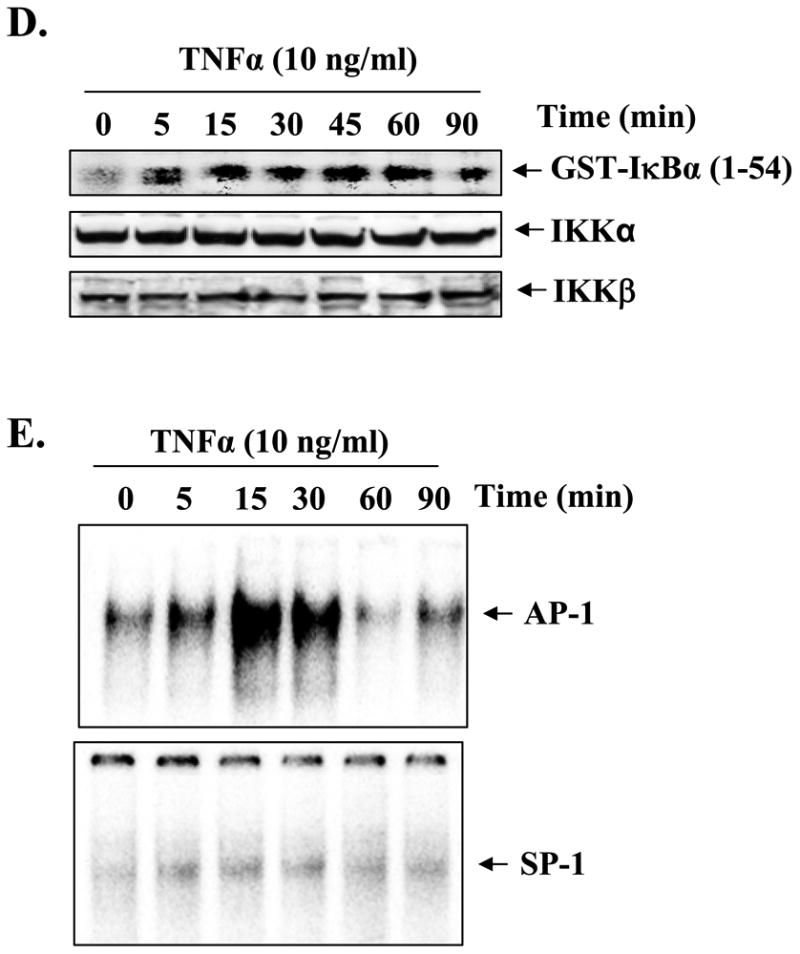

Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 Is Required for the TNF-α-induced Production of MMP-9 in C2C12 Myotubes

We next investigated whether TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 was responsible for the production of MMP-9 in myotubes. C2C12 myoblasts were transiently transfected with pcDNA3-FLAG-IκBαΔN (a dominant negative inhibitor of NF-κB) or pcDNA3-TAM-67 (a dominant negative mutant of c-Jun (33)). The myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in DM for 96 h followed by treatment with TNF-α. Interestingly, overexpression of either FLAG-IκBαΔN or TAM-67 protein blocked the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 from myotubes (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5. Role of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in muscle cells.

C2C12 myoblasts were transiently transfected with endotoxin-free pcDNA3 alone or FLAG-IκBαΔN-pcDNA3 or TAM-67-pcDAN3 plasmid followed by the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes by incubation in differentiation medium for 96 h. The myotubes were then treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) in serum-free medium for 14 h, and the production of MMP-9 in culture supernatants was measured by gelatin zymography. Data presented here show that overexpression of IκBαΔN (A) or TAM-67 (B) inhibits the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 in myotubes. C, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either wild-type human MMP-9 promoter-luciferase reporter construct (-670/+34) or with the promoter in which either AP-1 (-670/+34 AP-1m) or NF-κB (-670/+34 NF-κBm)-binding sites were mutated. The transfected myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in DM for 96 h. The myotubes were then treated with TNF-α for 18 h, and the activity of luciferase enzyme in cytoplasmic extracts was measured using a luciferase activity kit. Data presented here show that mutation in either AP-1- or NF-κB-binding sites inhibit the MMP-9 promoter-dependent expression of luciferase gene upon treatment with TNF-α. *, p < 0.05, values significantly different from TNF-treated myotubes transfected with wild-type construct (-670/+34).

The role of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors in TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in myotubes was also studied using a reporter gene (luciferase) assay in which the conserved AP-1- or NF-κB-binding sites in the human MMP-9 gene promoter were mutated (36). As shown in Fig. 5C, the MMP-9-promoter-dependent expression of the luciferase gene in response to TNF-α was significantly inhibited upon mutation of either AP-1- or NF-κB-binding sites.

Involvement of MAPK and PI3K/Akt Pathways in TNF-α-induced Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in Myotubes

Because inhibition of ERK1/2, p38, or PI3K/Akt kinases and AP-1 and NF-κB transcription factors blocked the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in myotubes, we investigated whether ERK1/2, p38, or PI3K/Akt constitute the molecular pathways that lead to the activation of NF-κB or AP-1 and hence the expression of Mmp-9 in myotubes in response to TNF-α. As shown in Fig. 6A, pretreatment of myotubes with PD98059 (MEK1/2 inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), or LY294002 (PI3K/Akt inhibitor) blocked the TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB. Similarly, the TNF-α-induced activation of AP-1 was also suppressed in the presence of PD98059 or SB203580 (Fig. 6B) but not LY294002. These data suggest that ERK1/2, p38, and PI3K/Akt are involved in TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB, whereas ERK1/2 and p38 mediates the TNF-α-induced activation of AP-1 in myotubes.

Fig. 6. Role of MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathway in activation of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors.

C2C12 myotubes were preincubated for 2 h with either PD98059 (50 μm), SB203580 (20 μm), or LY294002 (50 μm) followed by addition of TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 15 or 30 min. A, representative EMSA gel from two independent experiments presented here show that PD98059, SB203580, and LY294002 inhibits the TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κBin myotubes. B, activation of AP-1 in response to TNF-α was also inhibited in the presence of either PD98059 or SB203580 but not LY294002.

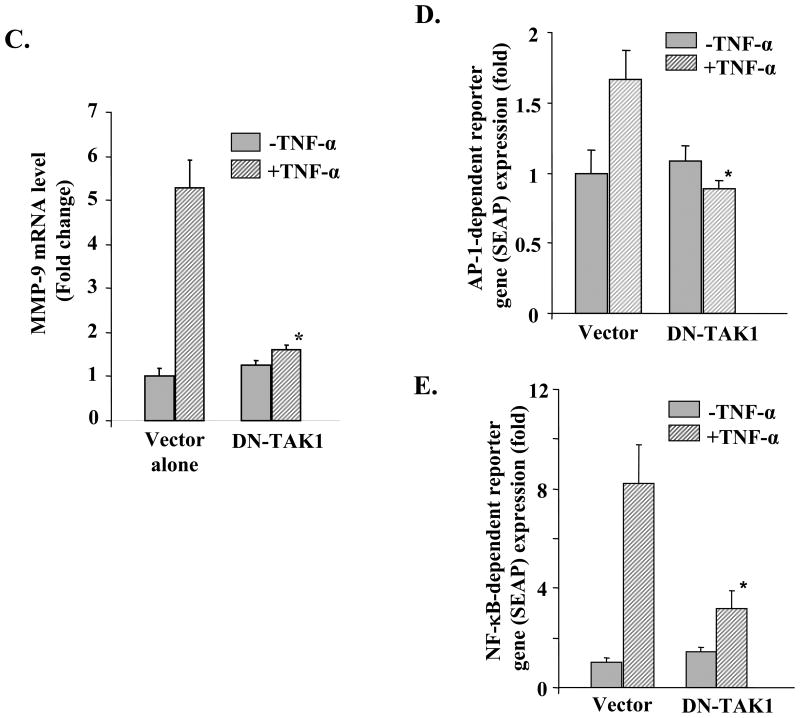

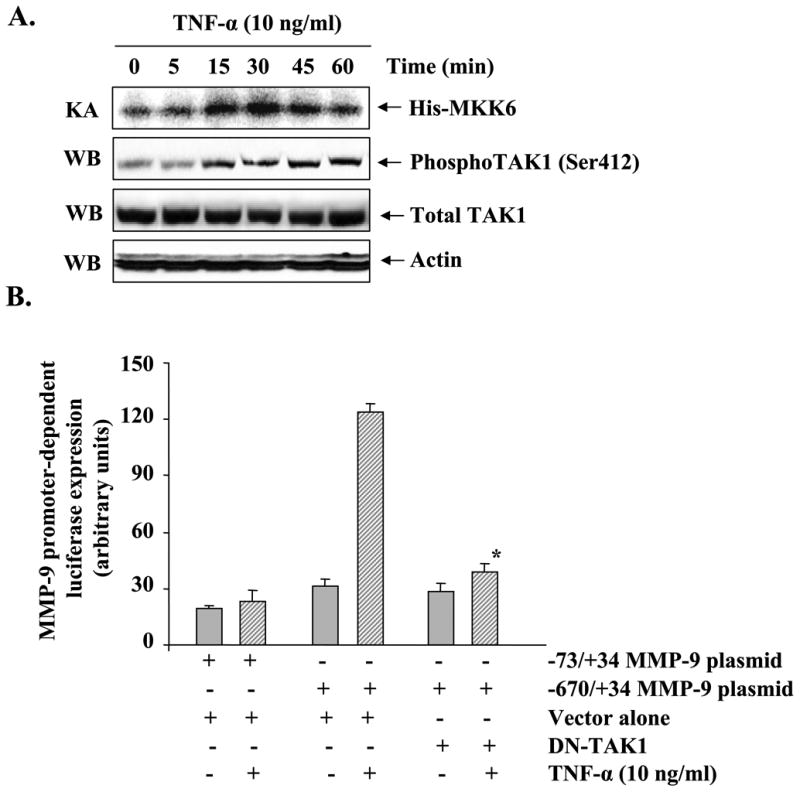

TAK1 Is Involved in TNF-α-induced Expression of MMP-9 in Myotubes

Accumulating evidence suggests that TAK1 plays the important role of second messenger in the activation of MAPK and NF-κB in response to several cytokines and endotoxins (26,44). To understand the upstream signaling mechanisms, we investigated whether TNF-α activates TAK1 in muscle cells and whether the activation of TAK1 is required for TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in cultured myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α for different time intervals, and the TAK1 activity was measured by immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay using His-MKK6 as substrate. Interestingly, treatment with TNF-α significantly enhanced the activation of TAK1 in myotubes (Fig. 7A, top panel). Furthermore, the level of phosphorylated TAK1 was also increased in response to TNF-α (Fig. 7A, 2nd panel). On the other hand, the total cellular level of TAK1 or an unrelated protein actin did not change on treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 7A, bottom panels). Taken together, these data indicate that TNF-α activates TAK1 in C2C12 myotubes.

Fig. 7. Involvement of TAK1 in TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes.

A, C2C12 myotubes were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for indicated time intervals. Measurement of kinase activity (KA) using His-MKK6 as a substrate showed that TNF-α increases the activation of TAK1 in myotubes (top panel). Western blot (WB) analysis using phospho-TAK1 antibody revealed that TNF-α increases the phosphorylation of TAK1 in myotubes (2nd panel from top). TNF-α did not affect cellular level of either TAK1 (3rd panel from top) or an unrelated protein actin (bottom panel) in C2C12 myotubes during this treatment time. B, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either vector alone or a dominant negative mutant of TAK1 (HA-TAK1K63W or DN-TAK1) along with MMP-9 reporter plasmid (i.e. -670/+34) in 1:10 ratio. The cells were differentiated into myotubes and incubated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 18 h followed by measurement of luciferase activity in cell extracts. Data presented here show that overexpression of DN-TAK1 inhibits the activation of the MMP-9 promoter in response to TNF-α. C, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either vector alone or DN-TAK1 plasmid and differentiated into myotubes by incubation in differentiation medium for 96 h. The myotubes were then treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 14 h and the expression of MMP-9 was studied by QRT-PCR. Data presented here show that overexpression of DN-TAK1 inhibits the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in myotubes. D and E, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either vector alone or DN-TAK1 plasmid along with a AP-1 (pAP-1-SEAP) or NF-κB (pNF-κB-SEAP) reporter plasmid in a 1:10 ratio followed by their differentiation into myotubes. These myotubes were then treated with TNF-α for additional 18 h, and the production of SEAP in culture supernatants was measured. Data presented here show that DN-TAK1 inhibits the TNF-α-induced transcriptional activation of AP-1 and NF-κB transcription factors in myotubes. *, p < 0.05 values significantly different from corresponding TNF-α-treated myotubes transfected with vector alone.

To understand the role of TAK1 in TNF-α-induced activation of MMP-9 promoter, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with a dominant negative TAK1 mutant (DN-TAK1 i.e. TAK1K63W) along with a human MMP-9 promoter reporter construct (-670/+34) in a 1:10 ratio. The myoblasts were then differentiated into myotubes and treated with TNF-α, and the reporter gene (luciferase) activity was assayed in cell extracts. As shown in Fig. 7B, overexpression of DN-TAK1 protein significantly inhibited the TNF-α-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter in myotubes. Furthermore, we also determined the effect of overexpression of DN-TAK1 on the mRNA levels of MMP-9. Consistent with MMP-9 promoter activity, overexpression of DN-TAK1 protein significantly inhibited the TNF-α-induced expression of the Mmp-9 gene in myotubes (Fig. 7C).

In another experiment, we also investigated whether TAK1 is involved in TNF-α-induced activation of AP-1 and NF-κB in myotubes. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with DN-TAK1 along with either pNF-kB-SEAP or pAP1-SEAP plasmid (in a 1:10 ratio) followed by differentiation into myotubes and treatment with TNF-α. Interestingly, overexpression of DN-TAK1 significantly blocked the TNF-α-induced transcriptional activation of AP-1 and NF-κB in myotubes (Fig. 7, D and E). These results indicate that TNF-α induces the expression of the Mmp-9 gene via TAK1-dependent activation of AP-1 and NF-κB transcription factors in skeletal muscle cells.

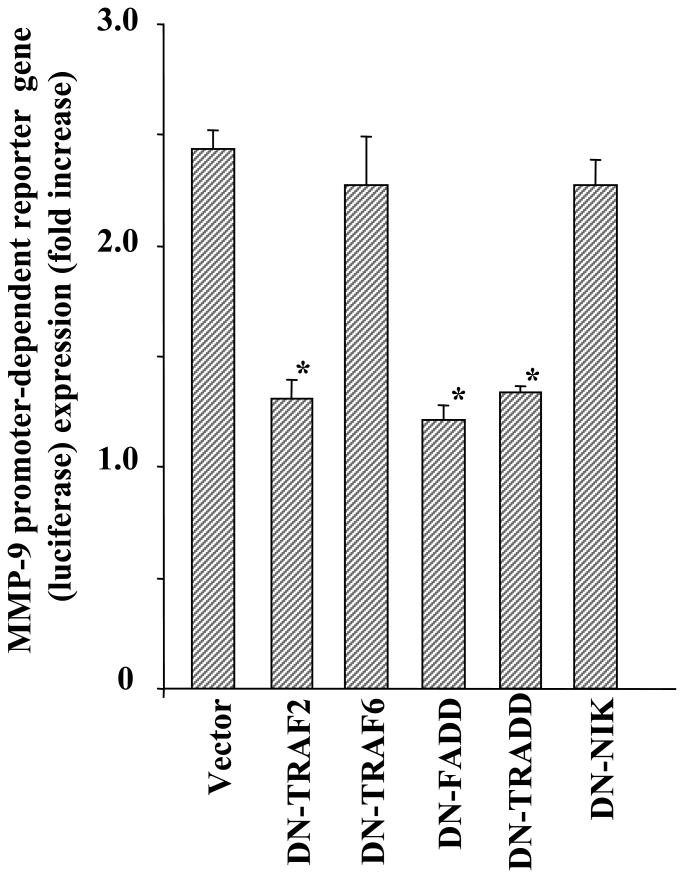

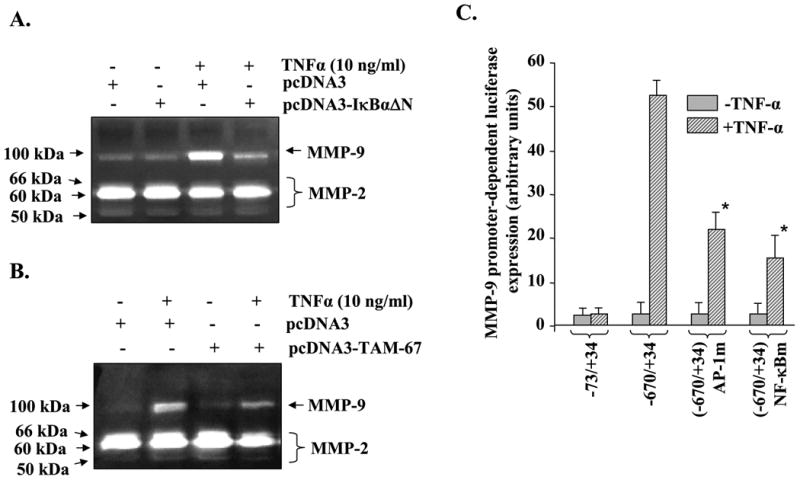

TRAF-2, TRADD, and FADD but Not TRAF-6 or NIK Are Involved in TNF-α-induced Activation of MMP-9 Promoter in Myotubes

TNF-α activates downstream signaling pathways through the sequential recruitment of a number of adaptor proteins such as TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) and the death domain homologues to TNF receptors (23,24). Accumulating evidence also suggests that TNF-α can activate NF-κB through NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)-dependent or -independent mechanisms (43,45,46). By overexpressing the dominant negative mutant of TRAF-2 (DN-TRAF2), dominant negative TRAF-6 (DN-TRAF6), dominant negative TRADD (DN-TRADD), dominant negative FADD (DN-FADD), and dominant negative NIK (DN-NIK) in myotubes, we investigated the role of these specific signaling proteins in TNF-α-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter. Interestingly, overexpression of DN-TRAF-2, DN-TRADD, and DN-FADD but not DN-TRAF-6 or DN-NIK inhibited the TNF-α-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter in skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 8). These data thus indicate that TRAF-2, TRADD, and FADD are the important components of a signaling pathway that leads to the expression of MMP-9 in skeletal muscle cells. Furthermore, these data also suggest that NIK is not involved in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in C2C12 myotubes.

Fig. 8. Role of TRAF-2, TRAF-6, TRADD, FADD, and NIK in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 production in myotubes.

C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either vector alone or with a dominant negative TRAF-2 (DN-TRAF-2), TRAF6 (DN-TRAF-6), FADD (DN-FADD), TRADD (DN-TRADD), or NIK (DN-NIK) plasmid along with the wild-type MMP-9 (-667/+32) reporter construct in a 1:10 ratio. The myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes by incubation in DM for 96 h. The myotubes were then treated with TNF-α for 18 h, and the luciferase activity in cell extracts was measured. Data presented here show that overexpression of DN-TRAF-2, DN-FADD, or DN-TRADD but not DN-TRAF-6 or DN-NIK significantly inhibits the TNF-α-induced activation of MMP-9 promoter in myotubes. *, p < 0.05, values significantly different from vector alone-transfected myotubes.

Discussion

MMPs are key modulators of many biological processes during pathophysiological events such as angiogenesis, cellular migration, inflammation, wound healing, coagulation, lung and cardiovascular diseases, arthritis, and cancer (47). Furthermore, clinical trials and studies in animal models of diseases have suggested that the inhibition of MMPs could be a potential strategy to prevent tissue degradations in various pathological conditions (48). However, the expression of MMPs and their tissue inhibitors in skeletal muscle and their potential role in the structural and physiological deterioration that occurs during many pathological conditions remain largely unknown. Because TNF-α is one of the most important cytokines that has been implicated in the induction of skeletal muscle atrophy in many chronic diseases (e.g. cancer, chronic heart failure, etc.), we investigated whether TNF-α could affect the expression of various MMPs and their inhibitors in skeletal muscle cells. Our microarray data (Table 1) followed by quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 1A), gelatin zymography (Fig. 1C), Western blotting (Fig. 1, D and E), and in vivo studies in mice (Fig. 1F) confirmed that TNF-α drastically increases the expression and release of MMP-9 from myotubes.

Specific MMPs are expressed during remodeling of ECM in both muscle development and regeneration (10). Lewis et al. (49) used zymography to investigate the activity of MMP-2 and -9 in conditioned media of cells derived from explants of the human masseter muscle and in the murine myoblast cell line C2C12. Irrespective of the origin of the cultures, MMP-9 activity was secreted only by single cell and pre-fusion cultures, whereas MMP-2 was secreted at all stages as well as by myotubes (49). Another group of investigators has also demonstrated that under basal conditions skeletal muscles of adult mice constitutively express MMP-2 (50). In contrast, MMP-9 was not detected either at the protein or the mRNA levels (50). Consistent with these published reports, our results suggest that MMP-2 but not MMP-9 is constitutively produced by C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the expression and release of MMP-9 from C2C12 myotubes were considerably augmented on treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 1). Interestingly, TNF-α did not affect the production of MMP-2 by C2C12 myotubes in cultures (Fig. 1, C and D) or upon in vivo administration in mice (data not shown). Because C2C12 is a pure skeletal muscle cell line (i.e. devoid of any fibroblasts and leukocytes), our data provide the first evidence that skeletal muscle cells by themselves can produce a large amount of MMP-9 in the extracellular environment on stimulation with TNF-α. Furthermore, because both MMP-2 and MMP-9 target similar substrates for degradation, enhanced proteolysis of ECM components in skeletal muscle tissues during pathological conditions could be attributed mainly to the increased production of MMP-9 by skeletal muscles.

Although TNF-α drastically increases the production of MMP-9 from muscle cells, it is possible that the increased expression of MMP-9 alone might not be sufficient for significant proteolysis of collagen in skeletal muscle. This is because the major components of skeletal muscle ECM are fibrillar collagen types I and III for which MMP-9 has minimum activity (51). However, increased production of MMP-9 may enhance the degradation of the skeletal muscle basement membrane that constitutes type IV collagen, a physiological substrate of MMP-9. Increased production of MMP-9 may also facilitate lymphocyte adhesion and enhance T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity by degradation of certain extracellular matrix proteins (52). Accumulating evidence also indicates that there is cooperative interaction between various MMPs to promote effective tissue degradation (8-10). Thus, MMP-9 might represent one of the many proteinases that facilitate the degradation of diverse matrix substrates leading to skeletal muscle tissue loss in various pathological conditions.

Several groups of investigators have reported that MAPKs constitute the signaling pathways that lead to the production of MMP-9. However, the role of individual MAPK (i.e. ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK) in the production of MMP-9 in response to TNF-α appears to be cell-specific. For example, ERK1/2 but not JNK or p38 MAPK was found to be involved in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in a human monocyte cell line (53). In human trophoblastic cells, TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression, secretion, and activity were completely blocked by JNK and ERK1/2 inhibitors but not by p38 MAPK inhibitors (54). On the other hand, the inhibition of ERK1/2 or p38 MAPK was sufficient to block the TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in vascular smooth muscle cells (55). However, in neutrophils, TNF-α activated both ERK1/2 and p38, but neither of these pathways was critical for MMP-9 release (56). Our data suggest that complete inhibition of either ERK1/2 or p38 alone is able to totally down-regulate MMP-9 expression in myotubes (Fig. 2, B and C). This means that when there is a complete inhibition of one pathway, activation of the other pathway is not sufficient to induce the Mmp-9 gene. Presumably, each pathway contributes to different transcription factors necessary for activation of the Mmp-9 promoter. This can explain why the absence of signal from either pathway would result in the complete inhibition of MMP-9. Similar to ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK, we observed that the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is also required for expression of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with published reports indicating a possible role for PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the production of MMP-9 in other cell types in response to specific signals (57).

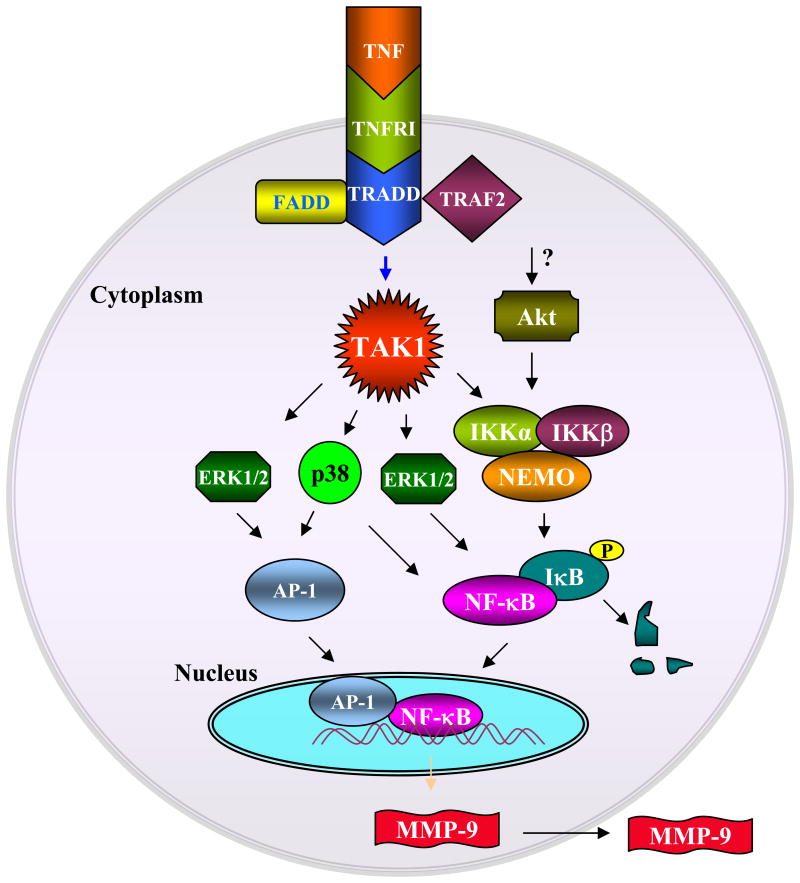

MMP-9 is highly regulated at three different levels as follows: transcriptional regulation, activation of latent MMP-9, and inhibition of MMP-9 activity by TIMPs (8). At the transcriptional level, the expression of the Mmp-9 gene is tightly controlled by the activation of specific transcription factors. Both mouse and human Mmp-9 promoters contain conserved consensus binding sequences for a number of nuclear transcription factors including AP-1, NF-κB, SP-1, Ets, and retinoblastoma-binding elements (41,42). These sites have been shown to be differentially responsive to various stimuli (58,59). Although the increased activation of NF-κB in response to TNF-α has been reported previously in skeletal muscle cells, including C2C12 myotubes (60,61), our study demonstrates that along with NF-κB TNF-α can also augment the activation of AP-1 transcription factor in myotubes (Fig. 4E and Fig. 7D). Furthermore, our results indicate that like ERK1/2, p38, and PI3K/Akt, transcriptional activation of both AP-1 and NF-κB is required for TNF-α-induced Mmp-9 gene expression in C2C12 myotubes. This contention is further supported by our experiments demonstrating that point mutations in either AP-1 or NF-κB sites were able to completely block the TNF-α-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter (Fig. 5C). In addition, we established that ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and Akt kinase are involved in TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors (Fig. 6) thus providing an important link between activation of upstream signaling pathways and expression of Mmp-9 gene in myotubes (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. A putative signaling pathway involved in the TNF-α-induced production of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes.

Binding of TNF-α to its receptor causes the recruitment of TRADD, FADD, and TRAF-2 proteins and activates TAK1. Activation of TAK1 leads to the activation of downstream kinases, including ERK1/2, p38, and IKK, which in turn leads to the activation of AP-1 or NF-κB transcription factors. TNF-α also activates Akt kinase, which leads to the activation of NF-κB transcription factor possibly through the activation of IKK. Activation and nuclear translocation of AP-1 and NF-κB results in the increased expression of the Mmp-9 gene resulting in production of the MMP-9 protein in extracellular environment.

TAK1 was first identified as transforming growth factor-β-activating kinase, but later studies have shown that TAK1 is critical for both interleukin-1β and TNF-α signaling (62). Activation of TAK1 complex, which also contains TAB1 and TAB2 protein, leads to the phosphorylation of IKKβ within the activation loop resulting in the activation of IKK complex (63). Furthermore, activated TAK1 complex can also phosphorylate another kinase of the MKK family such as MKK6, leading to the activation of JNK1 and p38 kinase (64). We investigated the role of TAK1 in TNF-α-induced Mmp-9 gene expression in myotubes. We observed that TNF-α rapidly activates TAK1 in C2C12 myotubes, and the activation of TAK1 was required for the TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors and the expression of Mmp-9 genes in myotubes (Fig. 7). This suggests that TAK1 can serve as an important molecular target to regulating the activation of proinflammatory transcription factors (e.g. AP-1 and NF-κB) and gene expression (e.g. MMP-9) in skeletal muscle (Fig. 9). Our study also suggests that TNF-α induces the production of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes mainly through the activation of the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. This is because overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of NIK, which is involved in the activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway (involves p100/p52 subunit of NF-κB) (65), did not affect the TNF-α-induced activation of the MMP-9 promoter in myotubes (Fig. 8). Furthermore, our experiments provide the evidence that TRADD, FADD, and ubiquitin ligase TRAF-2 constitute the signaling pathway that leads to enhanced production of MMP-9 in myotubes (Fig. 8). Based on the results in this study, we proposed a model that describes the role of various signaling proteins and transcription factors in TNF-α-induced expression of MMP-9 in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 9).

In summary, we provide the first evidence that TNF-α can induce the production of MMP-9 in skeletal muscle cells. Although more investigations are required to establish the in vivo cause-and-effect relationship between the production of MMP-9 and muscle structure and function, our study suggests that one of the mechanisms by which TNF-α may cause deterioration of skeletal muscle in vivo is through the increased production of MMP-9 by myofibers themselves. In future studies, it will also be important to identify the specific substrates that MMP-9 degrades in the skeletal muscle microenvironment in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant RO1 AG129623. We thank Dr. ShowWei Han, Dr. Jun Ninomiya-Tsuji, and Prof. Bharat B. Aggarwal for providing several plasmid constructs used in this study.

The abbreviations use are

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- DM

differentiation medium

- DN

dominant negative

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-related kinase

- FADD

Fas-associated protein with death domain

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NIK

NF-κB inducing kinase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- SEAP

secreted alkaline phosphatase

- TAK1

transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRAF

TNF-receptor associated factor

- TRADD

TNF receptor-associated protein with death domain

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- QRT-PCR

quantitative real time-PCR

- IKK

IκB kinase

References

- 1.Jackman RW, Kandarian SC. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C834–843. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00579.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandarian SC, Jackman RW. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:155–165. doi: 10.1002/mus.20442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanes JR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12601–12604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helbling-Leclerc A, Zhang X, Topaloglu H, Cruaud C, Tesson F, Weissenbach J, Tome FM, Schwartz K, Fardeau M, Tryggvason K, et al. Nat Genet. 1995;11:216–218. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jobsis GJ, Keizers H, Vreijling JP, de Visser M, Speer MC, Wolterman RA, Baas F, Bolhuis PA. Nat Genet. 1996;14:113–115. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer U. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14587–14590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michele DE, Campbell KP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15457–15460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vu TH, Werb Z. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2123–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.815400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmeli E, Moas M, Reznick AZ, Coleman R. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:191–197. doi: 10.1002/mus.10529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannelli G, De Marzo A, Marinosci F, Antonaci S. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:99–106. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reznick AZ, Menashe O, Bar-Shai M, Coleman R, Carmeli E. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:51–59. doi: 10.1002/mus.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach DM, Fitridge RA, Laws PE, Millard SH, Varelias A, Cowled PA. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:260–269. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kherif S, Dehaupas M, Lafuma C, Fardeau M, Alameddine HS. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998;24:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho RF, Dariolli R, Justulin Junior LA, Sugizaki MM, Politi Okoshi M, Cicogna AC, Felisbino SL, Dal Pai-Silva M. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87:437–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiotz Thorud HM, Stranda A, Birkeland JA, Lunde PK, Sjaastad I, Kolset SO, Sejersted OM, Iversen PO. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R389–R394. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00067.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YC, Dalakas MC. Neurology. 2000;54:65–71. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieseier BC, Schneider C, Clements JM, Gearing AJ, Gold R, Toyka KV, Hartung HP. Brain. 2001;124:341–351. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoser BG, Blottner D, Stuerenburg HJ. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105:309–313. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.1o104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YP, Reid MB. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:483–487. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spate U, Schulze PC. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:265–269. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal BB. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baud V, Karin M. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, Goeddel DV. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Oncogene. 2007;26:3214–3226. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakurai H, Suzuki S, Kawasaki N, Nakano H, Okazaki T, Chino A, Doi T, Saiki I. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36916–36923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, Lee KY, Bussey C, Steckel M, Tanaka N, Yamada G, Akira S, Matsumoto K, Ghosh S. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2668–2681. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acharyya S, Villalta SA, Bakkar N, Bupha-Intr T, Janssen PM, Carathers M, Li ZW, Beg AA, Ghosh S, Sahenk Z, Weinstein M, Gardner KL, Rafael-Fortney JA, Karin M, Tidball JG, Baldwin AS, Guttridge DC. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:889–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI30556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai D, Frantz JD, Tawa NE, Jr, Melendez PA, Oh BC, Lidov HG, Hasselgren PO, Frontera WR, Lee J, Glass DJ, Shoelson SE. Cell. 2004;119:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mourkioti F, Kratsios P, Luedde T, Song YH, Delafontaine P, Adami R, Parente V, Bottinelli R, Pasparakis M, Rosenthal N. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2945–2954. doi: 10.1172/JCI28721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dogra C, Changotra H, Mohan S, Kumar A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10327–10336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dogra C, Changotra H, Wedhas N, Qin X, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. FASEB J. 2007;21:1857–1869. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7537com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews CP, Birkholz AM, Baker AR, Perella CM, Beck GR, Jr, Young MR, Colburn NH. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2430–2438. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar A, Murphy R, Robinson P, Wei L, Boriek AM. FASEB J. 2004;18:1524–1535. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2414com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sitaraman SV, Roman J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29614–29624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Dhawan S, Mukhopadhyay A, Aggarwal BB. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:140–144. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar A, Chaudhry I, Reid MB, Boriek AM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46493–46503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dogra C, Hall SL, Wedhas N, Linkhart TA, Kumar A. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15000–15010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608668200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar A, Boriek AM. FASEB J. 2003;17:386–396. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0542com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorda M, Olmeda D, Vinyals A, Valero E, Cubillo E, Llorens A, Cano A, Fabra A. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3371–3385. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato H, Kita M, Seiki M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23460–23468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar A, Takada Y, Boriek AM, Aggarwal BB. J Mol Med. 2004;82:434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besse A, Lamothe B, Campos AD, Webster WK, Maddineni U, Lin SC, Wu H, Darnay BG. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3918–3928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608867200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malinin NL, Boldin MP, Kovalenko AV, Wallach D. Nature. 1997;385:540–544. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solan NJ, Miyoshi H, Carmona EM, Bren GD, Paya CV. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1405–1418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu J, Van den Steen PE, Sang QX, Opdenakker G. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:480–498. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fingleton B. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:333–346. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis MP, Tippett HL, Sinanan AC, Morgan MJ, Hunt NP. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2000;21:223–233. doi: 10.1023/a:1005670507906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kherif S, Lafuma C, Dehaupas M, Lachkar S, Fournier JG, Verdiere-Sahuque M, Fardeau M, Alameddine HS. Dev Biol. 1999;205:158–170. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Light N, Champion AE. Biochem J. 1984;219:1017–1026. doi: 10.1042/bj2191017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goetzl EJ, Banda MJ, Leppert D. J Immunol. 1996;156:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim KC, Lee CH. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:1257–1262. doi: 10.1007/BF02978209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen M, Meisser A, Haenggeli L, Bischof P. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:225–232. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho A, Graves J, Reidy MA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2527–2532. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chakrabarti S, Zee JM, Patel KD. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:214–222. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee CW, Lin CC, Lin WN, Liang KC, Luo SF, Wu CB, Wang SW, Yang CM. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L799–812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Behren A, Simon C, Schwab RM, Loetzsch E, Brodbeck S, Huber E, Stubenrauch F, Zenner HP, Iftner T. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11613–11621. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ray A, Bal BS, Ray BK. J Immunol. 2005;175:4039–4048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guttridge DC, Mayo MW, Madrid LV, Wang CY, Baldwin AS., Jr Science. 2000;289:2363–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li YP, Reid MB. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1165–1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, Matsumoto K, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1087–1095. doi: 10.1038/ni1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen ZJ, Bhoj V, Seth RB. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:687–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Senftleben U, Cao Y, Xiao G, Greten FR, Krahn G, Bonizzi G, Chen Y, Hu Y, Fong A, Sun SC, Karin M. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.