Abstract

Transgenic (Tg) mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been extensively used to study the pathophysiology of this dementia and to test the efficacy of drugs to treat AD. The 5XFAD Tg mouse, which contains two presenilin-1 and three amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutations, was designed to rapidly recapitulate a portion of the pathologic alterations present in human AD. APP and its proteolytic peptides, as well as apolipoprotein E and endogenous mouse tau, were investigated in the 5XFAD mice at 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months. AD and nondemented subjects were used as a frame of reference. APP, amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides, APP C-terminal fragments (CT99, CT83, AICD), β-site APP-cleaving enzyme, and APLP1 substantially increased with age in the brains of 5XFAD mice. Endogenous mouse tau did not show age-related differences. The rapid synthesis of Aβ and its impact on neuronal loss and neuroinflammation make the 5XFAD mice a desirable paradigm to model AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, transgenic mice, presenilin, amyloid precursor protein, BACE1, AICD, tau

Introduction

Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (SAD), the most common neurodegenerative disorder, is neuropathologically defined by amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT). The discovery of mutations in three genes that produce familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD), amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2), led to the development of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. This hypothesis contends that both SAD and FAD are caused by an excessive accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides as amyloid plaques in the extracellular space of the brain parenchyma and in cerebrovascular walls.

APP is a type 1 transmembrane protein whose gene is located on chromosome 21. This molecule is sequentially cleaved by β-site APP-cleaving enzyme (BACE)-1 and γ-secretase to generate Aβ peptides that accumulate in the brains of AD patients.1 Presently, 33 APP mutations are known to result in amyloid accumulation (http://www.molgen.vib-ua.be/AD Mutations). APP is ubiquitously expressed in cells throughout the body and its proteolytic products are thought to be involved in many functions such as the modulation of neuroprotection, neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation and migration, cell adhesion, synapse formation, neurite outgrowth, regulation of transcription, axonal transport,2 and regulation of the coagulation cascade.3–5

Gamma-secretase is a unique intramembrane protease complex responsible for amyloidogenic APP processing and is composed of PSEN1 or PSEN2, nicastrin, anterior pharynx-defective 1 (Aph-1), and presenilin enhancer-2 (Pen- 2).6 One hundred and eighty-five mutations have been described for the PSEN1 gene, located on chromosome 14, while 13 have been described for the PSEN2 gene, located on chromosome 1 (http://www.molgen.vib-ua.be/ADMutations). Importantly, there is evidence that PSEN has additional functions unrelated to γ-secretase activity, such as controlling the levels of the epidermal growth factor receptor, neuronal survival promotion, neuronal protection, inhibition of apoptosis, and regulation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3 pathway.7 Approximately 90 substrates for γ-secretase are known, and most are type 1 transmembrane signaling proteins that modulate a large number of cellular activities.8

The discovery of FAD mutations enabled the development of multiple lines of APP and PSEN transgenic (Tg) mice9 that have been extensively used for the development and testing of therapeutic interventions intended to modify the clinical course of SAD.10 However, only a minority of dementia patients (less than 2%) suffer from genetically-determined early-onset FAD. Expression of specific FAD mutations produces strikingly diverse pathogenic consequences in the Tg animals. Transgenic mice overexpressing APP mutations result in extensive amyloid plaque deposition, while PSEN Tg mice do not accumulate amyloid plaques, despite the presence of greatly elevated levels of Aβ42.11 However, PSEN Tg mice exhibit a broad range of neurodegeneration such as loss of neurons and synapses, as well as vascular pathology.11 Combining PSEN mutations with APP mutations in Tg mice results in a more severe amyloid plaque deposition compared to APP alone.11

An example of an enhanced amyloid pathology model is the 5XFAD Tg mouse.12 This Tg mouse line contains five FAD mutations: PSEN1 M146L, PSEN1 L286V, APP K670N/M671L (Swedish), APP I716V (Florida), and APP V717I (London).12–17 Detectable levels of Aβ42 are seen in these mice as young as 1.5 months, and the levels rapidly increase with age, resulting in the formation of amyloid plaques by 2 months.12,13,18 Aβ40 is also detected in these mice and increases with age, but not to the same magnitude as Aβ42.12,17 The 5XFAD Tg mice exhibit cognitive deficits starting at about 4 months of age.12–17 The appearance of aggregated intraneuronal Aβ immediately prior to amyloid plaque emergence suggests that amyloid plaques originate from intraneuronal Aβ deposits in these animals.12,19 In 5XFAD Tg mice, intraneuronal Aβ42 colocalizes with markers of both endosomes and lysosomes.18,20

APP and its C-terminal (CT) proteolytic peptide CT99, are sharply increased in the brains of 5XFAD Tg mice compared to wild type (wt) controls.17,21 In parallel with APP, the levels of BACE1 protein sharply increase with age in 5XFAD Tg mice, but without apparent changes in BACE1 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels.21–24 BACE1 localizes within dystrophic presynaptic neuron terminals that surround the amyloid plaques,22,25 as does PSEN1 and APP.23 The 5XFAD Tg mice express three fold more human APP molecules than endogenous mouse APP, and at 4–6 months, harbor enhanced levels of soluble Aβ oligomers compared to wt mice.13

A key phenotypic feature of the 5XFAD Tg mouse is the generation of neuronal loss, an attribute that is demonstrated in few other FAD Tg mice. By 9–12 months of age, the 5XFAD Tg mice have significant neuronal loss,12,18,26 which may begin to develop as early as 6 months.18 The observed neuronal deficits coincide with the areas of most intense Aβ42 deposits.18,26 Starting at 4 months of age, these mice also have increased activity of the apoptosis marker caspase-3 in areas of neuronal loss, intraneuronal Aβ42, and amyloid plaques.18 In addition, these mice exhibit motor and memory impairments, as well as reduced anxiety, related to neuronal loss and intraneuronal Aβ in layer 5 of some areas of the cerebral cortex, but sparing the hippocampus and the frontal cortex.26 A transcriptome analysis of frontal cortex and cerebellum from 7-week-old 5XFAD Tg mice, prior to amyloid plaque appearance, revealed alterations in the expression of genes related to cardiovascular disease and mitochondrial dysfunction, which were not observed in wt mice.27 The 5XFAD Tg mice also developed extensive astrogliosis and signs of neuroinflammation.12,28

Human AD patients exhibit a complex suite of specific biochemical pathologies and consequential global reactions that culminate in dementia. The construction of multigene Tg models has been driven by the desire to produce animals that recreate a broad array of the characteristic pathological alterations and deleterious reactions of SAD. We investigated Aβ accumulation, as well as the changes in APP/CT-APP in three different age groups of 5XFAD Tg mice. In addition, we examined the levels of BACE1, PSEN1, amyloid precursor-like protein 1 (APLP1), Fe65, apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and endogenous mouse tau in 5XFAD Tg mice. Human SAD and nondemented control (NDC) subjects were employed in this study to provide a frame of reference.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

Gray matter from the frontal cortex was obtained from neuropathologically confirmed SAD (n = 3) and NDC (n = 3) subjects provided by the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program.29 All operations have been approved by the Banner Health Institutional Review Board, and all subjects that enrolled in the Brain and Body Donation Program signed an informed consent form, approved by the Banner Health Institutional Review Board. All cases were male and ranged in age from 65–86 years.

Animals and brain harvest

The Tg6799 transgenic line of the 5XFAD mouse model of amyloidosis has been described previously,12 and was maintained on a B6/SJL F1 hybrid background. For brain harvest, mice of 3 months, 6 months, or 9 months of age were transcardially perfused with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, including 20 mg/mL of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 500 ng/mL of leupeptin (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA), 20 mM of sodium orthovanadate (MP Biomedicals), and 10 mM of dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich). A hemibrain from each mouse was dissected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C until used for biochemical analysis. Procedures were performed with Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Aβ40, Aβ42, and tau ELISA quantification

The following steps were all performed at 4°C. One hemisphere of Tg mouse cerebral cortex was gently homogenized with a Teflon tissue grinder (Sigma-Aldrich) in 800 μL of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 7.8, with a protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The mixture was then centrifuged at 430,000 × g for 20 minutes in a Beckman TLA 120.2 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Inc, Fullerton, CA, USA) and the soluble Aβ supernatant was collected. The remaining insoluble pellets were rehomogenized in 800 μL of 5 M guanidine hydrochloride (GHCl), 50 mM of Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 with an Omni TH electric grinder (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA, USA), shaken for 4 hours, centrifuged at 430,000 × g for 20 minutes in a Beckman TLA 120.2 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Inc) and the supernatant was collected. Total protein for the Tris-soluble and GHCl-soluble supernatants was determined with a Micro BCA™ Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Human Aβ1-40 and human Aβ1-42 were measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from Life Technologies Corporation (Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total mouse tau was also measured with an ELISA kit from Life Technologies Corporation, which utilizes antibodies that capture and detect total tau, regardless of the protein’s phosphorylation state.

Western blot analysis

All steps were completed at 4°C. Approximately 100 mg of human gray matter from the frontal lobe or one hemisphere of mouse cerebral cortex (all males) was homogenized in 1,000 μL of radioimmuno precipitation assay buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a PIC (Roche Diagnostics) and PhosSTOP (phosphatase inhibitor cocktail; Roche Diagnostics) using an Omni TH electric grinder. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes in a Beckman 22R centrifuge, the supernatant was collected and total protein determined with a Micro BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology). The proteins were heated for 10 minutes at 80°C in NuPage 2XLDS sample buffer (Life Technologies) with 50 mM of dithiothreitol and a total of 40 μg of protein was then separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) with NuPage 1XMES-SDS run buffer (Life Technologies) containing NuPage antioxidant (Life Technologies). A prestained molecular weight marker (Kaleidoscope; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was loaded onto each gel. After transferring the proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm pore) with NuPage transfer buffer (Life Technologies) and 20% methanol, the membranes were blocked in 5% Quick-Blocker (G-Biosciences, Maryland Heights, MO, USA) in PBS and 0.5% Tween 20. The primary and secondary antibodies used for Western blots are detailed in Table 1. All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in the same blocking buffer.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in Western blots.

| PRIMARY ANTIBODY | ANTIGEN SPECIFICITY OR IMMUNOGEN | SECONDARY ANTIBODY | COMPANY/CATALOG # |

|---|---|---|---|

| BACE1 | 3D5 clone, aa 46–460 | M | Provided by R. Vassar22 |

| PSEN1 | synthetic peptide, aa 25–50 of the N-terminus of human PSEN1 | R | Genscript/A00881 |

| 22C11 | APP aa 66–81 | M | Millipore/MAB348 |

| APLP1 | Mouse myeloma cell line ns0-derived recombinant human APLP1 | M | R&D Systems/MAB3908 |

| Fe65 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to residues of human Fe65 | R | Thermo Scientific/PA5–17432 |

| mCT20APP | C-terminal 20 aa of APP | M | Covance/SIG-39152 |

| pCT20APP | C-terminal 20 aa of APP | R | EMD Millipore/171610 |

| ApoE | Recombinant human ApoE | G | Millipore/AB947 |

| Actin Ab-5 | Clone C4 | M | BD Transduction Laboratories/A65020 |

| Actin | N-terminus of human α-actin | R | Abcam/Ab37063 |

Abbreviations: BACE, β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme; aa, amino acid; PSEN, presenilin; m, monoclonal; p, polyclonal; CT, C-terminal; APP, amyloid precursor protein; APLP1, amyloid precursor-like protein 1; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; M, HRP conjugated AffiniPure goat-anti mouse immunoglobulin G (catalog # 111-035-144, Jackson Laboratory); R, HRP conjugated AffiniPure goat-anti rabbit immunoglobulin G, (catalog # 111-035-146 Jackson Laboratory); G, HRP conjugated AffiniPure bovine-anti goat immunoglobulin G (catalog # 805-035-180).

To detect the APP intracellular domain (AICD), the methods of Pimplikar and Suryanarayana30 were employed. In brief, Western blots were performed as described above with the following changes: 1) 65 μg of total protein was loaded per lane; 2) proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes; 3) after transfer, antigen retrieval was performed by completely drying the membranes then boiling them in 1XPBS for 5 minutes; and 4) oversaturation of polyclonal CT20APP (pCT20APP; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and monoclonal CT20APP (mCT20APP, Covance) antibody concentration (1:1,000).

The proteins under study were visualized with Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology), CL-Xpose film (Pierce Biotechnology), and Kodak GBX developer and fixer (Sigma-Aldrich). All membranes were stripped with Restore™ Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce Biotechnology) and reprobed with anti-actin antibodies (Table 1) as a total protein-loading control. A GS-800 calibrated densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to digitize the films. The trace quantity feature in Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was implemented to determine the density of each band with the units being reported in intensity × mm.

Statistical analyses

Statistical calculations for ELISA data were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Group comparisons were analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskall–Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparison test. This method was used given the small sample size.

Results and Discussion

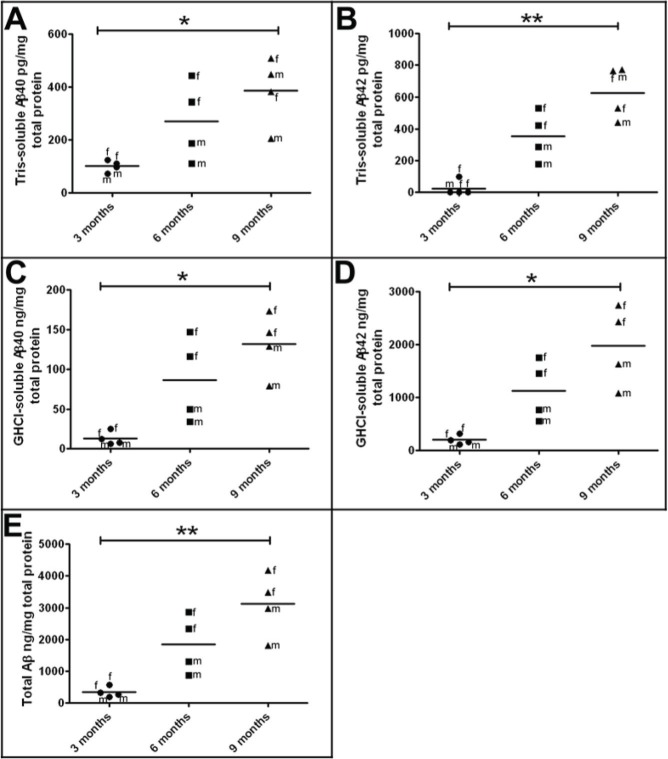

ELISA quantification of Tris-soluble and GHCl-soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 pools in whole brain homogenates of 5XFAD Tg mice revealed relatively low quantities of these peptides at 3 months of age, which increased sharply at 6 months and reached higher levels at 9 months (Fig. 1; Table 2). As previously reported,12 female 5XFAD Tg mice had higher Aβ levels than males, and this gender trend became more apparent as the mice aged (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Levels of soluble and insoluble human Aβ as quantified by ELISA in 3-month-old, 6-month-old, and 9-month-old 5XFAD Tg mice.

Notes: (A) Tris-soluble Aβ40 in pg/mg total protein. (B) Tris-soluble Aβ42 in pg/mg total protein. (C) GHCl-soluble Aβ40 in ng/mg total protein. (D) GHCl-soluble Aβ42 in ng/mg total protein. (E) Total Aβ (Tris-soluble and GHCl-soluble Aβ40 + Aβ42) in ng/mg total protein. Statistical analysis was performed using a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (*P = 0.05–0.01; **P = 0.01–0.001). The horizontal bars represent the mean of the four cases from each age group. For further details see Table 2.

Formulations: Tris = 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.8 buffer; GHCl = 5 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 buffer.

Abbreviations: f, female; m, male; Aβ, amyloid-beta; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FAD, familial Alzheimer’s disease; GHCI, guanidine hydrochloride; EDTA, ethylenediaminetraacetic acid.

Table 2.

Human Aβ and mouse endogenous tau ELISA results in the 5XFAD Tg mice.

| PROTEIN | MEAN CONCENTRATION | SEM | p = |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-soluble Aβ40 (pg/mg total protein) | 0.0296 | ||

| 3 months | 101 | 11 | |

| 6 months | 271 | 75 | |

| 9 months | 386 | 66 | |

| Tris-soluble Aβ42 (pg/mg total protein) | 0.0091 | ||

| 3 months | 25 | 25 | |

| 6 months | 354 | 77 | |

| 9 months | 627 | 84 | |

| GHCl-soluble Aβ40 (ng/mg total protein) | 0.0183 | ||

| 3 months | 13 | 4 | |

| 6 months | 87 | 27 | |

| 9 months | 132 | 20 | |

| GHCl-soluble Aβ42 (ng/mg total protein) | 0.0154 | ||

| 3 months | 199 | 42 | |

| 6 months | 1133 | 281 | |

| 9 months | 1971 | 376 | |

| Total Aβ (ng/mg total protein) | 0.0125 | ||

| 3 months | 338 | 80 | |

| 6 months | 1844 | 459 | |

| 9 months | 3114 | 500 | |

| Tris-soluble tau (ng/mg total protein) | 0.2866 | ||

| 3 months | 52 | 10 | |

| 6 months | 76 | 10 | |

| 9 months | 70 | 11 | |

| GHCl-soluble tau (ng/mg total protein) | 0.6939 | ||

| 3 months | 200 | 21 | |

| 6 months | 180 | 16 | |

| 9 months | 197 | 11 | |

| Total tau (ng/mg total protein) | 0.7788 | ||

| 3 months | 252 | 31 | |

| 6 months | 255 | 12 | |

| 9 months | 267 | 21 |

Formulations: Tris = 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.8 buffer; GHCl = 5 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 buffer. Total tau is the sum of Tris- and GHCl-soluble tau. Statistical analyses were performed using a Kruskal–Wallis test. Total Aβ is the sum of Aβ40 and Aβ42 for both Tris- and GHCl-soluble fractions.

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid-beta; SEM, standard error of the mean.

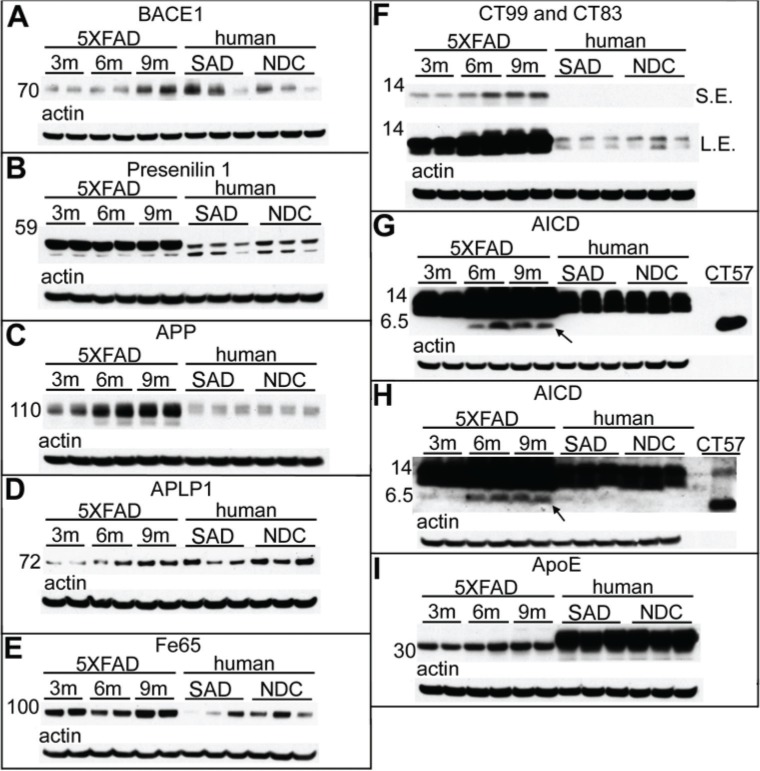

In agreement with previously published observations,21–24 BACE1 levels increased with age among the 5XFAD Tg mice, with an average 3.3-fold elevation observed between 3 months to 9 months of age (Fig. 2A; Table 3). The mean amount of BACE1 in the 9-month-old Tg mice was similar to the mean observed in the SAD cohort (Fig. 2A; Table 3). PSEN1, a doublet band at 55 kDa on Western blots, was overexpressed in 5XFAD Tg mice in comparison to human SAD and NDC subjects, but they exhibited no further change in levels in the 5XFAD aging brain (Fig. 2B; Table 3).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of male 5XFAD Tg mice at 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months of age, as well as human SAD and NDC gray matter from the frontal cortex.

Notes: (A) The mature form of BACE1 shown at ~70 kDa. (B) Full-length presenilin-1 (~55 kDa). (C) Full-length APP as detected by 22C11. (D) Full-length APLP1. (E) The adaptor protein Fe65. (F) CT99 and CT83 of APP as detected by mCT20APP. SE and LE are both shown. The putative AICD (denoted by an arrow) can be detected in older mice by antigen retrieval and by greatly increasing the antibody concentration and total protein per lane as detected with mCT20APP (G) and pCT20APP (H) antibodies. A purified CT–APP peptide of 57 amino acids (rPeptide, Athens, GA, USA) is shown on the right side of the blots in (G) and (H). (I) Full-length ApoE is observed at ~34 kDa. All blots were stripped and reprobed with actin (shown below each primary antibody) as quantitative protein loading control. A total of 40 μg of total protein was loaded into each lane for (A–F) and (I), while 65 μg of total protein was loaded into each lane for (G) and (H). For antibody details, see Table 1. The molecular weight markers are shown to the left of each blot and are reported in kDa. For further details, see Table 3.

Abbreviations: BACE, β-site APP-cleaving enzyme; APLP, amyloid-precursor-like protein; CT, C-terminal; APP, amyloid precursor protein; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; SAD, sporadic Alzheimer’s disease; NDC, nondemented controls; m, months; SE, short exposure; LE, long exposure.

Table 3.

Scanning densitometry results from Western blot experiments.

| 5XFAD Tg MOUSE AGE | FIGURE 2 LANE # | BACE1 | PRESENILIN 1 | APP | APLP1 | Fe65 | ApoE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 m | 1 | 0.388 | 3.743 | 0.960 | 0.217 | 1.702 | 1.740 |

| 3 m | 2 | 0.407 | 4.008 | 1.376 | 0.188 | 1.988 | 1.510 |

| Mean | 0.398 | 3.876 | 1.168 | 0.203 | 1.845 | 1.625 | |

| 6 m | 3 | 0.462 | 3.500 | 2.380 | 0.378 | 0.846 | 2.040 |

| 6 m | 4 | 0.502 | 3.446 | 3.179 | 0.872 | 1.309 | 2.693 |

| Mean | 0.482 | 3.473 | 2.780 | 0.625 | 1.078 | 2.367 | |

| 9 m | 5 | 1.085 | 3.645 | 3.256 | 1.387 | 2.522 | 2.911 |

| 9 m | 6 | 1.541 | 3.561 | 3.250 | 1.144 | 2.229 | 2.556 |

| Mean | 1.313 | 3.603 | 3.253 | 1.266 | 2.376 | 2.734 | |

| Human subjects | |||||||

| SAD | 7 | 1.781 | 0.623 | 0.411 | 1.636 | 0.000 | 9.187 |

| SAD | 8 | 1.153 | 0.460 | 0.481 | 0.460 | 0.199 | 9.570 |

| SAD | 9 | 0.266 | 0.339 | 0.575 | 0.785 | 0.970 | 10.234 |

| Mean | 1.067 | 0.474 | 0.489 | 0.960 | 0.390 | 9.664 | |

| NDC | 10 | 0.911 | 1.027 | 0.575 | 1.737 | 0.608 | 11.039 |

| NDC | 11 | 0.534 | 0.630 | 0.460 | 1.151 | 1.378 | 9.885 |

| NDC | 12 | 0.194 | 0.698 | 0.554 | 2.193 | 0.043 | 10.964 |

| Mean | 0.546 | 0.785 | 0.530 | 1.694 | 0.676 | 10.629 | |

Data from Western blots shown in Figure 2. Films were scanned with a GS-800 calibrated densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the trace quantity feature in Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to determine the density of each band. The units are reported in intensity × mm.

Abbreviations: m, months; SAD, sporadic Alzheimer’s disease; NDC, nondemented control; BACE, β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme; APP, amyloid precursor protein; APLP, amyloid precursor-like protein; ApoE, apolipoprotein E.

Western blots confirmed that APP levels increased with age in the 5XFAD Tg mice (Fig. 2C). The 9-month-old Tg mice overexpressed APP 6.4-fold above the mean levels observed in human SAD and NDC subjects (Fig. 2C; Table 3). Even at 3 months, the 5XFAD Tg mice had 2.3 times more APP than the human subjects (Fig. 2C; Table 3). Likewise, APLP1, also a substrate of γ-secretase,31–33 increased with age in the 5XFAD Tg cohort (Fig. 2D). There was a 6.2-fold increase in APLP1 levels among mice between 3 months and 9 months of age (Fig. 2D; Table 3). The human cases (mean of NDC and SAD) contained similar quantities of APLP1 as the 9-month-old 5XFAD Tg mice (Fig. 2D; Table 3). Although APLP1 may not be directly altered by the transfected genes in this Tg model, the observed elevation of APLP1 with age may affect transcription of other APP family members since APLP1, by sequestering the adaptor protein Fe65, regulates the nuclear translocation of the intracellular domains of APP and APLP2.34 In the 5XFAD Tg mice the Fe65 molecule is modestly elevated at 9 months of age compared to 3- and 6-month-old mice (Fig. 2E) but, intriguingly, at 9 months of age, the 5XFAD Tg mice had, on average, about 4.5-fold more Fe65 than the mean amount detected in SAD and NDC (Fig. 2E; Table 3), although there is considerable variation in the levels of this protein in human subjects.

CT–APP fragments were dramatically increased in 5XFAD Tg mice relative to humans (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, production of the amyloidogenic precursor of Aβ peptides, the APP-CT99 fragment, increased with Tg mouse age (Fig. 2F). In addition, in the 5XFAD Tg mice, CT99 production was enhanced relative to the level of CT83, the precursor of the nonamyloidogenic P3 fragment (Aβ17-40/42) (Fig. 2F). Modifications to the Western blot technique, such as increased total protein, overloading of antibody concentration and antigen retrieval, allowed for the detection of the elusive AICD in 6-and 9-month-old Tg mice, which was detected by both mCT20 APP (Fig. 2G) and pCT20 APP (Fig. 2H) antibodies, following the increasing age-related pattern of Aβ, CT99, and CT83 production. The AICD was below the limit of detection in our human samples (Fig. 2G and Fig. 2H) and most likely requires a massive overproduction of APP and PSEN by genetic manipulations to be observed in Western blots. Difficulties in the detection of the AICD may be due to its short half-life35 or to its interaction with about 20 known proteins, as reviewed by Pardossi-Piquard and Checler,36 which could mask the AICD antigenic determinants required for antibody detection. As mentioned above, the AICD is a transcription factor that binds to Fe65. This interaction may be responsible for controlling the proteolytic processing of APP, since increases in the levels of Fe65 also increase the levels of Aβ.37

The preferential production of the APP-CT99 fragment may reflect the fact that BACE1 levels also increased with advancing age (Fig. 2A), there by favoring the generation of amyloidogenic Aβ peptides. Although the BACE1 protein increases with age in 5XFAD Tg mice, BACE1 mRNA levels have been reported to remain unchanged.21–24 This may be due to an increase in the efficiency of RNA translation or to enhanced BACE1 stability or activity. Nevertheless, production of CT99 (Fig. 2F), Aβ (Fig. 1), and AICD (Figs. 2G and 2H) concomitantly increase. When 5XFAD Tg mice were crossed with BACE1−/− mice, Aβ40, Aβ42, and soluble oligomeric Aβ levels decreased to levels typically seen in wt mice, while the APP and PSEN1 amounts remained high.13 Interestingly, 5XFAD Tg mice crossed with BACE1−/− did not exhibit neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, memory difficulties, or amyloid plaque deposition, suggesting that Aβ contributes directly to neuron loss and other deleterious cellular events in this model.28

Although SAD is classically linked to abnormal amyloid accumulation, additional evidence suggests that the induction of neurotoxicity may be mediated by the direct participation of both Aβ and CT–APP fragments operating through alternative pathophysiological mechanisms.38 The neurotoxic effects in 5XFAD Tg mice may reflect the increased production of free or membrane-bound toxic CT99 species (Fig. 2F), the main precursor of the AICD.39 This gross disturbance of the APP processing equilibrium may have the additional dual consequence of enhancing production of the AICD (Figs. 2G and 2H), which may directly induce the expression of genes leading to apoptosis,40–43 or favoring the generation of neurotoxic peptides such as the proapoptotic APP-CT31, released by caspase proteolysis.44–46

The levels of ApoE were modestly increased with age (1.7-fold) between the 3- and 9-month-old 5XFAD Tg mice (Fig. 2I; Table 3). In AD, as well as in other APP Tg mice models, endogenous ApoE colocalizes with amyloid plaques and substantially increases with age as Aβ accumulates in these lesions.47 The dynamic coexistence of these molecules suggests that ApoE is an essential component for Aβ accumulation and may act as a transporter and/or inducer of amyloid fibrillar polymerization. In the absence of ApoE in general or, specifically ApoEε4, some APP Tg mice exhibit a significant delay in Aβ deposition, an observation that lends support to these contentions.48–50

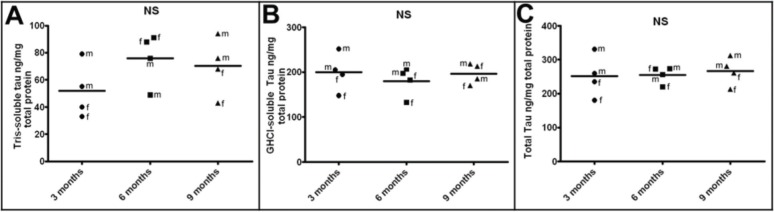

One hypothesis relating to the neurodegenerative etiology and evolution of SAD is that excessive amyloid deposition induces tau hyperphosphorylation, which results in NFT accumulation.51–53 Intriguingly, no corresponding elevations in Tris-soluble (Fig. 3A; Table 2) or GHCl-soluble (Fig. 3B; Table 2) mouse endogenous tau were observed in 5XFAD Tg mice with increasing age. Although, no NFT or p-tau staining was observed in 5XFAD Tg brain sections using the AT8 antibody,12 the presence of other p-tau epitopes by either immunohistochemistry or Western analysis has not been investigated in this model. The inability of massive Aβ loads to cause NFT in 5XFAD Tg mice may reflect species differences in tau or in the induction of NFT. Alternatively, it is possible that amyloid plaques and NFT simply form independently of each other and therefore do not accumulate in a sequential manner in the 5XFAD Tg mice.54–57

Figure 3.

ELISA quantification of endogenous mouse tau at 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months of age.

Notes: (A) Tris-soluble tau in ng/mg total protein. (B) GHCl-soluble tau in ng/mg total protein. (C) Total tau (Tris + GHCl soluble fractions) in ng/mg total protein. Statistical analysis was performed using a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. The horizontal bars represent the mean of the 4 cases from each age group. For further details see Table 2.

Formulations: Tris = 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.8 buffer; GHCl = 5 M guanidine hydrochloride 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 buffer.

Abbreviations: NS, not significant; f, female; m, male; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GHCI, guadinine hydrochloride; EDTA, ethylenediaminetraacetic acid.

Conclusions

The 5XFAD Tg mice rapidly recapitulate a portion of the pathologic alterations present in human SAD and FAD. In particular, the putative Aβ-reactive phenotypes in these mice make them desirable models to assess the rapid synthesis of Aβ and its impact on neuronal loss and neuroinflammation. These mice utilize a combination of well-characterized genes present in early-onset FAD to induce a specific and swift upsurge in amyloidogenic APP processing, leading to increased Aβ and CT-APP peptide production, including the AICD, with potential pathologic activities. The 5XFAD Tg mice exhibit a range of behavioral and biochemical phenotypes associated with AD (importantly, neuronal loss). However, these mice do not mimic all facets of human AD, most notably exhibiting a lack of NFT.12 Although it seems likely that the FAD genes utilized in these mice partially duplicate key molecular cascades observed in AD, the biochemical pathways may have been profoundly perturbed. For example, the 5XFAD model exhibit unusual responses such as intracellular and extracellular Aβ in the spinal cord,26 and alterations of genes related to cardiovascular disease and mitochondrial dysfunction as early as 7 weeks.27 In particular, the PSEN/γ-secretase activities impact an extraordinarily broad range of substrates,8 with potentially grave pleiotropic interactions on vital neuronal, glial, and vascular functions.11,58–60

Transgenic mice have been successfully utilized in the exploration of specific disease mechanisms to examine protein interactions and to define unique biochemical pathways associated with AD pathology. However, mouse models have demonstrated limitations in their ability to successfully predict drug efficacy in humans.61–63 Specifically, many Aβ-targeted therapies rescue amyloid pathology and memory deficits in AD Tg mouse models, but do not translate to humans for the treatment of AD. Potentially, APP Tg mice may recapitulate an early stage of AD, while humans with AD have much more advanced and complicated disease conditions and, thus, are refractory to Aβ-targeted therapy. In addition, this conundrum could be a consequence of the vast phylogenetic distance that separates humans from rodents in terms of anatomy, physiology, and life span, and the immense complexity of the human brain that culminated in the creation of our culture. Therefore, being aware of the strengths and limitations of Tg mice models will significantly aid in the interpretation of data resulting from these important paradigms.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Jointly developed study design, structure and arguments for the paper: AER, CLM, RV. Data collection: CLM, RV, MNS, TGB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: CLM, AER, RV, TAK, TGB, MNS, CMW, MPM, WMK. All authors reviewed and approved the final conclusions of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

FUNDING: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grants R01 AG019795 (AER), R01 AG022560 (RV), and R01 AG030142 (RV). The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS0702026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium), and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS: CLM, TAK, CMW, MPM, WMK and AER have no conflicts of interest. MNS receives grant/contract support from Pfizer, Eisai, Neuronix, Lilly, Avid, Piramal, GE, Avanir, Elan, Functional Neuromodulation and is on the advisory board for Biogen, Lilly, Piramal, Eisai and receives royalties from Wiley and Tenspeed (RandomHouse). TGB is a consultant for GE Healthcare and receives research funding from AVID-Radiopharmaceuticals, Schering-Bayer Pharmaceuticals, GE Healthcare, Piramal Radiopharmaceuticals and Navidea. RV is a consultant for Eisai, Lilly, and Vitae Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Müller UC, Pietrzik CU, Deller T. The physiological functions of the β-amyloid precursor protein APP. Exp Brain Res. 2012;217:3–4. 325–329. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou ZD, Chan CH, Ma QH, Xu XH, Xiao ZC, Tan EK. The roles of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in neurogenesis: Implications to pathogenesis and therapy of Alzheimer disease. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5(4):280–292. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.4.16986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Nostrand WE, Schmaier AH, Farrow JS, Cunningham DD. Platelet protease nexin-2/amyloid beta-protein precursor. Possible pathologic and physiologic functions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;640:140–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahdi F, Van Nostrand WE, Schmaier AH. Protease nexin-2/amyloid beta-protein precursor inhibits factor Xa in the prothrombinase complex. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(40):23468–23474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry A, Li QX, Galatis D, et al. Inhibition of platelet activation by the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein. Br J Haematol. 1998;103(2):402–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spasic D, Annaert W. Building gamma-secretase: the bits and pieces. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 4):413–420. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neve RL. Alzheimer’s disease sends the wrong signals—a perspective. Amyloid. 2008;15(1):1–4. doi: 10.1080/13506120701814608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haapasalo A, Kovacs DM. The many substrates of presenilin/γ-secretase. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25(1):3–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall AM, Roberson ED. Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duff K, Suleman F. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: how useful have they been for therapeutic development? Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2004;3(1):47–59. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/3.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder GA, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Dickstein DL, Hof PR. Presenilin transgenic mice as models of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:2–3. 127–143. doi: 10.1007/s00429-009-0227-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(40):10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohno M, Chang L, Tseng W, et al. Temporal memory deficits in Alzheimer’s mouse models: rescue by genetic deletion of BACE1. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(1):251–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura R, Ohno M. Impairments in remote memory stabilization precede hippocampal synaptic and cognitive failures in 5XFAD Alzheimer mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33(2):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohno M. Failures to reconsolidate memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92(3):455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girard SD, Baranger K, Gauthier C, et al. Evidence for early cognitive impairment related to frontal cortex in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(3):781–796. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura R, Devi L, Ohno M. Partial reduction of BACE1 improves synaptic plasticity, recent and remote memories in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2010;113(1):248–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eimer WA, Vassar R. Neuron loss in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease correlates with intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation and Caspase-3 activation. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon M, Hong HS, Nam DW, et al. Intracellular amyloid-β accumulation in calcium-binding protein-deficient neurons leads to amyloid-β plaque formation in animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(3):615–628. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youmans KL, Tai LM, Kanekiyo T, et al. Intraneuronal Aβ detection in 5xFAD mice by a new Aβ-specific antibody. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devi L, Ohno M. Genetic reductions of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 and amyloid-beta ameliorate impairment of conditioned taste aversion memory in 5XFAD Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31(1):110–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J, Fu Y, Yasvoina M, et al. Beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 levels become elevated in neurons around amyloid plaques: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27(14):3639–3649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4396-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XM, Cai Y, Xiong K, et al. Beta-secretase-1 elevation in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease is associated with synaptic/axonal pathology and amyloidogenesis: implications for neuritic plaque development. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30(12):2271–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor T, Sadleir KR, Maus E, et al. Phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2alpha increases BACE1 levels and promotes amyloidogenesis. Neuron. 2008;60(6):988–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandalepas PC, Sadleir KR, Eimer WA, Zhao J, Nicholson DA, Vassar R. Erratum to: The Alzheimer’s β-secretase BACE1 localizes to normal presynaptic terminals and to dystrophic presynaptic terminals surrounding amyloid plaques. Acta Neuropathol. 2013 Sep 5; doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1152-3. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jawhar S, Trawicka A, Jenneckens C, Bayer TA, Wirths O. Motor deficits, neuron loss, and reduced anxiety coinciding with axonal degeneration and intraneuronal Aβ aggregation in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(1):196.e29–196.e40. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim KH, Moon M, Yu SB, Mook-Jung I, Kim JI. RNA-Seq analysis of frontal cortex and cerebellum from 5XFAD mice at early stage of disease pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(4):793–808. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohno M, Cole SL, Yasvoina M, et al. BACE1 gene deletion prevents neuron loss and memory deficits in 5XFAD APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26(1):134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, et al. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9(3):229–245. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pimplikar SW, Suryanarayana A. Detection of APP intracellular domain in brain tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;670:85–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-744-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheinfeld MH, Ghersi E, Laky K, Fowlkes BJ, D’Adamio L. Processing of beta-amyloid precursor-like protein-1 and -2 by gamma-secretase regulates transcription. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(46):44195–44201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh DM, Fadeeva JV, LaVoie MJ, et al. gamma-Secretase cleavage and binding to FE65 regulate the nuclear translocation of the intracellular C-terminal domain (ICD) of the APP family of proteins. Biochemistry. 2003;42(22):6664–6673. doi: 10.1021/bi027375c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eggert S, Paliga K, Soba P, et al. The proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein gene family members APLP-1 and APLP-2 involves alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and epsilon-like cleavages: modulation of APLP-1 processing by n-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18146–18156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gersbacher MT, Goodger ZV, Trutzel A, Bundschuh D, Nitsch RM, Konietzko U. Turnover of amyloid precursor protein family members determines their nuclear signaling capability. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cupers P, Orlans I, Craessaerts K, Annaert W, De Strooper B. The amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cytoplasmic fragment generated by gamma-secretase is rapidly degraded but distributes partially in a nuclear fraction of neurones in culture. J Neurochem. 2001;78(5):1168–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardossi-Piquard R, Checler F. The physiology of the β-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain AICD. J Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bórquez DA, González-Billault C. The amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain-fe65 multiprotein complexes: a challenge to the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease? Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:353145. doi: 10.1155/2012/353145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang KA, Suh YH. Pathophysiological roles of amyloidogeniccarboxy-terminal fragments of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97(4):461–471. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flammang B, Pardossi-Piquard R, Sevalle J, et al. Evidence that the amyloid-β protein precursor intracellular domain, AICD, derives from β-secretase-generated C-terminal fragment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(1):145–153. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passer B, Pellegrini L, Russo C, et al. Generation of an apoptotic intracellular peptide by gamma-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta protein precursor. J Alzheimers Dis. 2000;2:3–4. 289–301. doi: 10.3233/jad-2000-23-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakayama K, Ohkawara T, Hiratochi M, Koh CS, Nagase H. The intracellular domain of amyloid precursor protein induces neuron-specific apoptosis. Neurosci Lett. 2008;444(2):127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozaki T, Li Y, Kikuchi H, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Nakagawara A. The intracellular domain of the amyloid precursor protein (AICD) enhances the p53–mediated apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinoshita A, Whelan CM, Berezovska O, Hyman BT. The gamma secretase-generated carboxyl-terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein induces apoptosis via Tip60 in H4 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(32):28530–28536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu DC, Rabizadeh S, Chandra S, et al. A second cytotoxic proteolytic peptide derived from amyloid beta-protein precursor. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):397–404. doi: 10.1038/74656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galvan V, Chen S, Lu D, et al. Caspase cleavage of members of the amyloid precursor family of proteins. J Neurochem. 2002;82(2):283–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu DC, Soriano S, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Caspase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein modulates amyloid beta-protein toxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;87(3):733–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuo YM, Crawford F, Mullan M, et al. Elevated A beta and apolipoprotein E in A beta PP transgenic mice and its relationship to amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med. 2000;6(5):430–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bales KR, Verina T, Dodel RC, et al. Lack of apolipoprotein E dramatically reduces amyloid beta-peptide deposition. Nat Genet. 1997;17(3):263–264. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bales KR, Verina T, Cummins DJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E is essential for amyloid deposition in the APP(V717F) transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(26):15233–15238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holtzman DM, Bales KR, Tenkova T, et al. Apolipoprotein E isoform-dependent amyloid deposition and neuritic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(6):2892–2897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050004797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12(10):383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Tseng BP, LaFerla FM. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(8):1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Götz J, Schild A, Hoerndli F, Pennanen L. Amyloid-induced neurofibrillary tangle formation in Alzheimer’s disease: insight from transgenic mouse and tissue-culture models. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22(7):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schönheit B, Zarski R, Ohm TG. Spatial and temporal relationships between plaques and tangles in Alzheimer-pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(6):697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(3):358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. Mechanism of Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration and the formation of tangles. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2(3):178–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wegiel J, Bobinski M, Tarnawski M, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta affects neurofibrillary changes but only in neurons already involved in neurofibrillary degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101(6):585–590. doi: 10.1007/s004010000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gama Sosa MA, Gasperi RD, Rocher AB, et al. Age-related vascular pathology in transgenic mice expressing presenilin 1-associated familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(1):353–368. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong PC, Zheng H, Chen H, et al. Presenilin 1 is required for Notch1 and DII1 expression in the paraxial mesoderm. Nature. 1997;387(6630):288–292. doi: 10.1038/387288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen J, Bronson RT, Chen DF, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, Tonegawa S. Skeletal and CNS defects in presenilin-1-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89(4):629–639. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geerts H. Of mice and men: bridging the translational disconnect in CNS drug discovery. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(11):915–926. doi: 10.2165/11310890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, et al. Inflammation and Host Response to Injury, Large Scale Collaborative Research Program. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(9):3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kokjohn TA, Roher AE. Amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models and Alzheimer’s disease: understanding the paradigms, limitations, and contributions. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(4):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]