Abstract

Atrioesophageal fistula is a rare yet devastating complication of trans-catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. This condition requires urgent intervention, but the optimal treatment strategy has not been defined. Reported therapies range from endoscopic stenting to direct atrial repair or reconstruction on cardiopulmonary bypass. Here we describe the successful management of an atrioesophageal fistula via cervical esophageal ligation and decompression along with gastric drainage.

Keywords: Esophageal injury/perforation, Esophageal surgery, Fistula (Atrioesophageal), Ablative therapy

Atrioesophageal fistula is a rare but potentially fatal complication of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. It is the second most frequent fatal complication (after cardiac tamponade) with a reported incidence of 0.03 – 1% [1, 2] and a mortality of 71 – 83% [1, 3]. Causes of death include cerebral air embolism, massive gastrointestinal bleeding, and septic shock. There is no consensus regarding the best treatment. We report a patient with a left atrioesophageal fistula successfully managed with cervical esophageal diversion and gastric drainage.

A 59 year old man with a history of chronic atrial fibrillation underwent percutaneous, trans-septal left atrial ablation with a ThermoCool® radiofrequency catheter. Atrial ablation included circumferential burns around the four pulmonary veins, the atrial roof, and mitral isthmus lines. Six weeks later he presented with chest pain, diaphoresis, headache, fever, and altered mental status. Blood cultures revealed bacteremia with multiple streptococcal species. Subsequent echocardiograms were unable to identify any evidence of endocarditis. He improved with antibiotics, but then became acutely aphasic with a right hemiplegia. An MRI of the brain showed pneumocephalus and areas of ischemia in multiple vascular distributions. A thin barium esophagram followed by a computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a retrocardiac esophageal-atrial fistula tract (Figure 1A), and air in the left atrium (Figure 1B). Atrial repair was considered; however, it was felt that the degree of fragility of a large portion of the left atrial wall and probable lack of healthy tissue for adequate closure precluded primary repair. He had no evidence of mediastinitis. To reduce the amount of soilage of the fistula and to optimize healing, we performed esophageal ligation and decompression via a cervical approach, gastrostomy, and jejunostomy.

Figure 1.

A) CT of the chest demonstrating oral contrast within fistulous tract between esophagus and left atrium. B) Air within left atrium

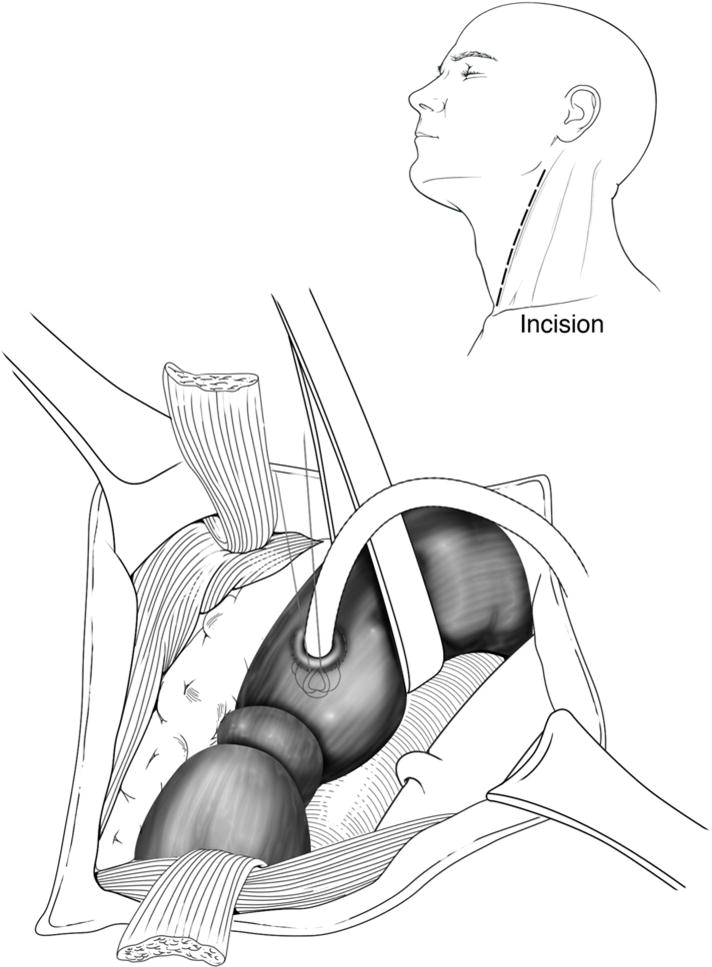

An incision was made in the left neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid to expose the esophagus. Two Prolene sutures were tied around the distal-most esophagus and tagged with metal clips for later identification. The esophagus was decompressed with an 18-French Malecot drain through a separate stab incision (Figure 2). A Stamm gastrostomy and feeding jejunostomy were then performed. The postoperative course was remarkable for transient atrial fibrillation. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on post-operative day #10 with intravenous antibiotics for 4 weeks, and enteral nutrition.

Figure 2.

Ligation and decompression technique used for treatment of atrioesophageal fistula.

The patient was readmitted one month later due to mental status changes and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. He was again found to be bacteremic, and was placed on another course of antibiotics. The GI bleeding resolved with cessation of therapeutic anticoagulation (Lovenox) which had been started for transient ischemic attack-like symptoms. The neurologic symptoms were found to be due to seizures, and resolved with anti-seizure medication. A repeat esophagram demonstrated minimal contrast traversing the occluded esophagus. Despite this re-canalization of the esophagus, there was no atrioesophageal fistula identified.

Two months after the initial diversion the patient’s ambulation and speech were dramatically improved, and imaging studies showed only a diverticulum at the site of the previous fistula. The esophageal ligatures were removed via a local neck exploration, and he was discharged on clear liquids the same day. One week later, a follow-up esophagram showed free passage of contrast into the stomach with minimal stenosis at the esophageal ligature site. The small diverticulum persisted at the site of the previous fistula, but there was no evidence of a remnant tract or fistula. Currently, he is tolerating a regular diet with no dysphagia.

Comment

Patients with atrioesophageal fistula typically present 3 to 38 days after cardiac ablation [4], with a mean of 12 days (range, 10 to 16 days) [5]. Presenting symptoms usually include fever, malaise, dysphagia, chest pain, neurologic symptoms, gastrointestinal bleeding, and sepsis. A high level of suspicion for atrioesophageal fistula should exist for patients with these symptoms and a recent atrial ablative procedure. Esophagram with thin barium or water-soluble contrast may show extravasation of material in communication with the atrium. This should be followed immediately by CT of the chest, which may be diagnostic if air is visualized in the mediastinum or heart, or if intravenous contrast enters the esophagus from the left atrium. Transthoracic echocardiography is typically non-diagnostic, but is important to exclude endocarditis. Endoscopy and transesophageal echocardiography should be avoided, as they may increase fistula size and/or increase the risk of food or air embolism secondary to instrumentation and insufflation. [6]

Urgent intervention is necessary after diagnosis of an atrioesophageal fistula, but there is currently no standard treatment. Management options previously reported include esophageal stenting, and direct intracardiac or transthoracic extracardiac repair with or without cardiopulmonary bypass [4, 7, 8]. This typically involves variations of a left or right thoracotomy, atrial and esophageal repair with interposition of a muscle flap or pericardium, and mediastinal drainage. No mortality rates from these procedures have been reported, but hospital stays have been as long as 5 weeks [4]. There is only one case report of successful esophageal stenting [7]. In another report, the patient rapidly deteriorated during a transesophageal echocardiogram [6], demonstrating the dangers of esophageal instrumentation in the presence of an atrioesophageal fistula.

Our therapeutic strategy included a short operative time (3 hours), the avoidance of cardiopulmonary bypass or manipulation of an air-filled atrium, and access for gastric drainage and enteral nutrition. It also avoided any esophageal manipulation that would occur during esophagoscopy and stent placement. The patient had a short length of stay, and no major complications. He has had near complete restoration of neurologic function, and is eating a regular diet. In appropriately selected patients without mediastinitis, this approach should be considered to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with more aggressive procedures. More experience with this procedure and its outcomes is needed to more accurately define its role in the treatment algorithm of atrioesophageal fistulas, but the results of this case are encouraging. Cervical diversion and gastric drainage should be in the armamentarium of the thoracic surgeon, and considered in patients with an atrioesophageal fistula and a high likelihood for cerebral air embolus.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by: Vanderbilt Physician Scientist Development Award (E.L.G.)

References

- 1.Ghia KK, Chugh A, Good E, et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of atrioesophageal fistula after left atrial radiofrequency catheter ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009;24(1):33–6. doi: 10.1007/s10840-008-9307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilcrease GW, Stein JB. A delayed case of fatal atrioesophageal fistula following radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21(6):708–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, et al. Prevalence and causes of fatal outcome in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(19):1798–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazavet A, Muscari F, Marachet MA, Leobon B. Successful surgery for atrioesophageal fistula caused by transcatheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(3):e43–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Brief communication: atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):572–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonmez B, Demirsoy E, Yagan N, et al. A fatal complication due to radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: atrio-esophageal fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(1):281–3. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunch TJ, Nelson J, Foley T, et al. Temporary esophageal stenting allows healing of esophageal perforations following atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(4):435–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khandhar S, Nitzschke S, Ad N. Left atrioesophageal fistula following catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: off-bypass, primary repair using an extrapericardial approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):507–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]