Abstract

Background

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT) is most commonly caused by transplacental passage of maternal human platelet-specific alloantigen (HPA)-1a antibodies that bind to fetal platelets (PLTs) and mediate their clearance. SZ21, a monoclonal antibody (MoAb) directed against PLT glycoprotein IIIa, competitively inhibits the binding of anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies to PLTs in vitro. The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments might be therapeutically effective in inhibiting or displacing maternal HPA-1a antibodies from the fetal PLT surface and preventing their clearance from circulation.

Study Design and Methods

Resting human PLTs from HPA-1ab heterozygous donors were injected into nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodefi-cient (NOD/SCID) mice. Purified F(ab′)2 fragments of SZ21 or control immunoglobulin G (IgG) were injected intraperitoneally 30 minutes before introduction of HPA-1a antibodies. Blood samples were taken periodically and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of circulating human PLTs.

Results

Anti-HPA-1a IgG from NAIT cases were able to efficiently clear HPA-1a–positive PLTs from murine circulation. Administration of SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments not only inhibited binding of HPA-1a antibodies to circulating human PLTs, preventing their clearance, but also displaced bound HPA-1a antibodies from the PLT surface.

Conclusion

F(ab′)2 fragments of HPA-1a–selective MoAb SZ21 effectively inhibit anti-HPA-1a–mediated clearance of human PLT circulating in an in vivo NOD/SCID mouse model. These results suggest that agents that inhibit binding of anti-HPA-1a to PLTs may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of NAIT.

Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT) results from maternal alloimmunization to paternally inherited human platelet-specific alloantigens (HPA) expressed on the surface of fetal platelets (PLTs)1. The transplacental passage of maternal HPA-1a antibodies leads to destruction of fetal PLTs. Of the 16 alloantigen systems identified to date, HPA-1a antibodies are the most frequent cause of severe thrombocytopenia in Caucasian persons2,3. A single Leu33Pro amino acid polymorphism is responsible for the HPA-1a alloimmunization4. The manifestations of NAIT range from subclinical thrombocytopenia to intracranial hemorrhage, the latter of which occurs in 10 to 20 percent of the NAIT cases1. Although most intracranial hemorrhage cases are reported to occur in utero, NAIT-affected newborns are also at risk to develop cerebral hemorrhage, especially in the first 24 to 48 hours postpartum1.

Owing to the absence of a routine screening program to predict maternal HPA alloimmunization, first-pregnancy NAIT cases are usually identified postnatally. These cases require immediate management of severe thrombocytopenia to achieve a rapid correction of PLT count to prevent intracranial hemorrhage in the neonates. Currently, HPA-1a–negative PLT transfusion is the treatment of choice1. Because only 2.5 percent of Caucasian persons are HPA-1bb, the availability of HPA-1a–negative PLTs is restricted to major transfusion centers3. Other therapeutic options such as high-dose intravenous globulin and random PLT transfusion have some limitations, like delay of action and refractoriness1,5,6. Therefore, there is a need for novel therapeutic approaches that might efficiently prevent clearance of newborn PLTs.

SZ21, a monoclonal antibody (MoAb) directed against PLT glycoprotein (GP) IIIa, binds at or near the HPA-1a epitope7-9. Recently, we developed an in vivo model system in which human PLTs are injected into nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice and allowed to circulate for up to 24 hours10. Using this model, it is possible to investigate the fate of human PLTs in the presence of PLT-reactive antibodies and to examine the potential for novel therapeutics to prevent PLT clearance. In this study, we show that coinjection of divalent F(ab′)2 fragments of SZ21 prevents anti-HPA-1a– mediated human PLT clearance from the circulation.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) fractions were isolated from three different anti-HPA-1a serum samples implicated in NAIT cases using an IgG purification gel as described by the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, IL). F(ab′)2 fragments of SZ21 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) were prepared using a F(ab′)2 preparation kit (Pierce). The purity and the binding capacity of the IgG and F(ab′)2 preparation were assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and flow cytometry. Isotype-matched F(ab′)2 was obtained from Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). AP2, which recognizes a complex-dependent epitope on GPIIb-IIIa, was provided by Dr Robert R. Montgomery (Blood Research Institute, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI)11.

Antibody binding studies

Whole blood was drawn from HPA-1ab or HPA-1bb donors into acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD), supplemented with 50 ng per mL prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 minutes. PLT-rich plasma was collected and supplemented with 50 ng per mL PGE1 and centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 minutes. The PLT pellet was resuspended with modified Tyrodes-HEPES (Tyrode-N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid) buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.4], 12 mol/L NaHCO3, 137 mol/L NaCl, 2.7 mol/L KCl, 5 mol/L glucose, 0.25% bovine serum albumin), and the PLT concentration was adjusted to 2.0 × 108 per mL. Fifty microliters of PLT suspension from both allotypes was incubated with the indicated concentrations of SZ21 F(ab′)2. Binding of SZ21 F(ab′)2 was detected using anti-mouse F(ab′) (goat anti-mouse F(ab), 1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). In experiments designed to examine the ability of SZ21 F(ab′)2 to block anti-HPA-1a binding, PLTs were obtained from an HPA-1ab, blood group O donor and incubated with SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments at concentrations ranging from 0.25-12 μg per mL for 30 minutes at 25°C. After washing, PLTs were incubated with anti-HPA-1a or control IgG (500 μg/mL, 1 hr, at 37°C), washed with 1 mL of HEN buffer (100 mmol/L HEPES, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetate, 50 mol/L NaCl, pH 7.4), centrifuged at 720 × g for 3 minutes, resuspended in 50 μL of donkey anti-human Fc-fragment antibody (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), and analyzed by flow cytometry. To investigate whether SZ21 F(ab′)2 could displace prebound HPA-1a antibodies from the PLT surface, HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with anti-HPA-1a for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT). Thereafter, 10 mg per mL SZ21 F(ab′)2 was added for 15, 30, 45, or 60 minutes at RT. PLTs were washed with 1 mL of HEN buffer, incubated with 50 μL of a mixture of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled donkey anti-human Fc-fragment (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) and PE-labeled goat anti-mouse F(ab)-fragment (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Introduction of human PLTs into NOD/SCID mice

Human PLTs from HPA-1ab donors were prepared as previously described12. Briefly, blood was drawn into ACE and supplemented with PGE1 at 50 ng per mL. After 10 minutes at RT, blood was centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 minutes. Washed PLTs were prepared as described previously, resuspended in autologous human plasma at 2.0 × 109 per mL, supplemented with PGE1 to 50 ng per mL, allowed to rest for 30 minutes, and injected into the retroorbital plexus of age- and sex-matched NOD/SCID mice (Stock No. complexes, 001303; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Thirty micrograms of SZ21 or control F(ab′)2 fragments in 200 μL of sterile Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline was injected intraperitoneally (IP) immediately after introducing the human PLTs. After a blood sample was taken to establish baseline human PLT counts, 800 μg of maternally derived anti-HPA-1a or control IgG was injected IP. Blood samples of 20 to 50 μL were taken periodically via tail tip amputation into 1 mL of a 1:9 mixture of 3.8 percent sodium citrate/Tyrodes-HEPES buffer containing PGE1 at 50 ng per mL. The blood mixture was layered onto 2 mL of Fico/Lite PLTs (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 350 × g, and the PLT layer (1 mL) added to 3.0 mL Tyrodes-HEPES buffer supplemented with 67 ng per mL PGE1. PLTs were washed by centrifugation at 750 × g for 10 minutes, resuspended in 50 μL Tyrodes-HEPES buffer and the percentage of circulating human PLTs was determined by flow cytometry using FITC-labeled AP2.

Results and Discussion

SZ21 F(ab′)2 binds preferentially to HPA-1a-positive PLTs and inhibits anti-HPA-1a binding in vitro

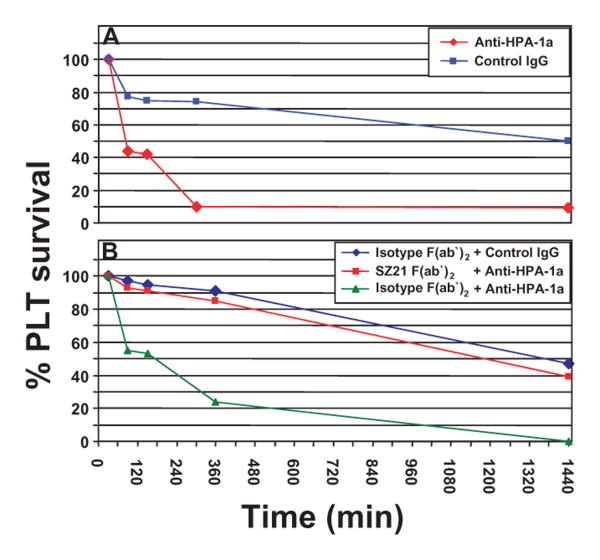

To confirm the selective binding of SZ21 to the HPA-1a, rather than 1b, allelic form of GPIIIa, we assessed the binding of SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments to HPA-1ab and HPA-1bb PLTs. As shown in Fig. 1A, SZ21 F(ab′)2 binds selectively to the HPA-1a epitope. To determine whether SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments might be able to competitively inhibit binding of maternal anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies to PLTs in vitro, HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with 5 μg per mL SZ21 or control F(ab′)2 for 30 minutes at RT before incubation with 500 μg per mL IgG from NAIT sera. While no inhibition was observed using an isotype-matched control, pretreatment of PLTs with SZ21 F(ab′)2 resulted in a significant reduction in anti-HPA-1a binding to PLTs (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrate that SZ21 competitively inhibits binding of human HPA-1a antibodies.

Fig. 1.

SZ21 F(ab′)2 inhibits maternal anti-HPA-1a binding to PLTs in vitro. (A) SZ21 F(ab′)2 preferentially binds HPA-1a-PLTs. PLTs from HPA-1ab (black line) and -bb (green line) donors were incubated with 5 μg per mL SZ21 F(ab′)2, and binding was detected using an antibody specific for mouse F(ab) fragment. Median fluorescence values are indicated. Note that SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments preferentially bind HPA-1a-positive PLTs. (B) SZ21 F(ab′)2 inhibits human anti-HPA-1a binding to PLTs. HPA-1ab PLTs were coated with SZ21 F(ab′)2 (green line) or isotype-matched F(ab′)2 (black line; 5 μg/mL, 30 min, RT) before the incubation with IgG from maternal HPA-1a-serum. (C) SZ21 F(ab′)2 disassociates prebound HPA-1a antibodies from human PLT surface in vitro. HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with IgG isolated from maternal HPA-1a serum (500 μg/mL, 30 min, RT). SZ21 F(ab′)2 was then added (10 μg/mL) and the PLTs were incubated at RT for an additional 15, 30, 45, or 60 minutes. Binding of SZ21 F(ab′)2 and anti-HPA-1a was detected using antibodies specific for mouse F(ab) and human Fc-fragment, respectively. Note that addition of SZ21 F(ab′)2 causes a measurable reduction of anti-HPA-1a binding in as little as 15 minutes and the removal of anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies from the PLT surface was essentially complete within 1 hour.

To investigate whether SZ21 F(ab′)2 might be able to displace prebound HPA-1a alloantibodies from the PLT surface, HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with anti-HPA-1a for 30 minutes at RT. Next, SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments were added, and the amount of HPA-1a antibodies remaining on the PLT surface was determined by two-color flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1C, SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments were able to effectively displace HPA-1a alloantibodies from the PLT surface in a time-dependent manner. Removal of anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies began in as little as 15 minutes after addition of SZ21 F(ab′)2 and was essentially complete within 1 hour. No decrease in bound HPA-1a antibodies was observed using the isotype-matched GPIIb/IIIa-specific MoAb AP2 (data not shown). These results demonstrate that SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments are able to disassociate HPA-1a antibodies from the human PLT surface in vitro and provide a rationale for examining the potential of SZ21 F(ab′)2 to protect antigen-positive PLTs from maternal anti-HPA-1a–mediated clearance in vivo.

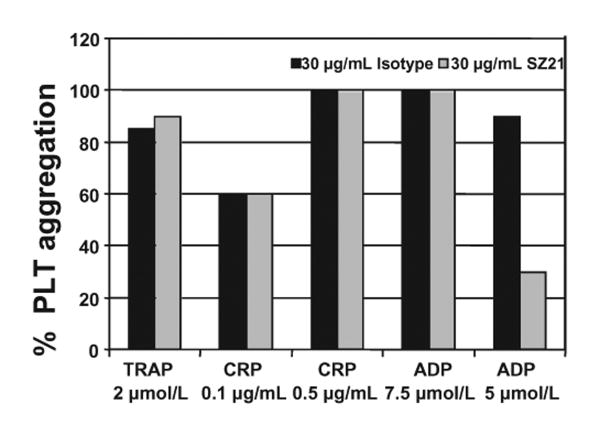

SZ21 F(ab′)2 efficiently inhibits anti-HPA-1a-mediated clearance of human antigen-positive PLTs from circulation

To examine the ability of SZ21 F(ab′)2 to prevent maternal anti-HPA-1a– mediated clearance of HPA-1ab heterozygous PLTs in vivo, we employed a recently developed NOD/SCID mouse model of human PLTs circulating in mice10. As shown in Fig. 2A, IP injection of maternal serum-derived anti-HPA1a IgG results in rapid clearance of human HPA-1ab PLTs from circulation, whereas normal human IgG has no significant effect. Notably, when mice were injected with as little as 1.5 μg per g body weight of SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments 30 minutes before introduction of human PLTs, their clearance was largely prevented (Fig. 2B). This result is representative of three independent experiments using IgG from three different anti-HPA-1a–mediated NAIT cases and demonstrates the potential for SZ21 to be used to reverse thrombocytopenia in severe cases of NAIT.

Fig. 2.

Blockade of anti-HPA-1a–mediated PLT clearance by SZ21 F(ab′)2. (A) Maternal anti-HPA-1a mediates PLT clearance in vivo. Resting human HPA-1ab PLTs were injected retroorbitally into NOD/SCID mice. Maternal anti-HPA-1a-IgG (red line) or control IgG (blue line) was injected IP, and the percentage human PLTs remaining in circulation was evaluated through periodic blood sampling by flow cytometry. (B) SZ21 F(ab′)2 inhibits anti-HPA-1a-mediated PLT clearance. SZ21 F(ab′)2 or isotype-matched F(ab′)2 (1.5 μg/g) was injected IP directly after introduction of human PLTs as described in A. Blood samples were taken immediately before the IP injection of 50 μg per g human anti-HPA-1a or normal control IgG. The percentage of circulating human PLTs was determined through mouse bleeding at 30, 90, 150, and 360 minutes and 24 hours. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments using IgG from three different anti-HPA-1a-mediated NAIT cases.

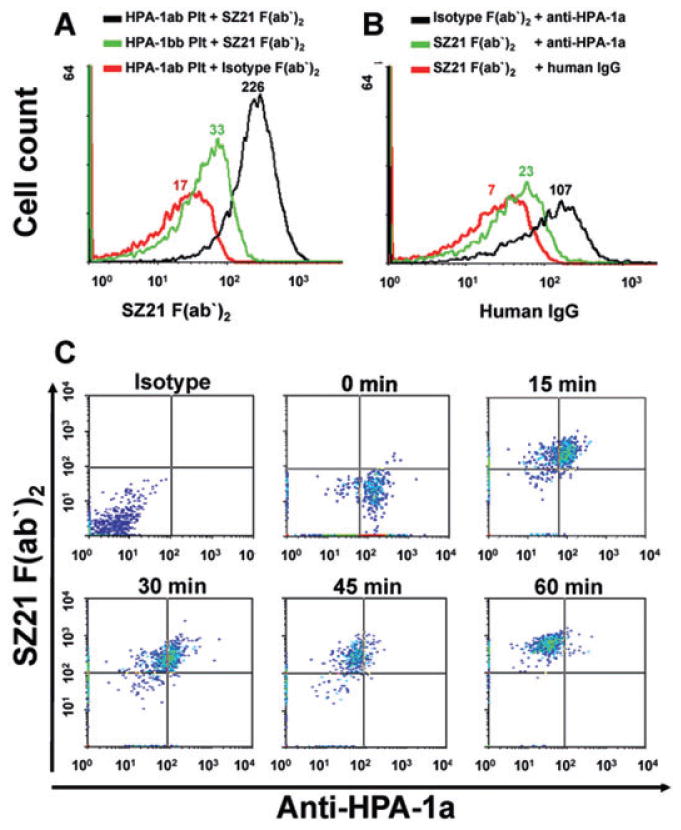

SZ21 has been previously shown to inhibit the aggregation of HPA-1aa homozygous PLTs13. Because the fetal PLTs in NAIT that serve as targets for maternal anti-HPA-1a alloantibodies are necessarily heterozygous for HPA-1, and because SZ21 at low concentrations binds poorly to the HPA-1b allelic isoform of GPIIIa (Fig. 1A), approximately 50 percent of the GPIIb-IIIa receptors on the fetal PLT surface should, in theory, remain free to mediate fibrinogen binding and PLT aggregation. To determine whether HPA-1ab PLTs coated with SZ21 might indeed remain responsive to PLT agonists, their ability to aggregate and undergo granule secretion in response to a range of different stimuli was evaluated by lumiaggregometry. As shown in Fig. 3, SZ21 had little effect on PLT aggregation induced by 2 μmol per L thrombin receptor–activating peptide, 0.1 or 0.5 μg per mL collagen-related peptide, or 7.5 μmol per L adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP). It did, however, inhibit by approximately 60 percent aggregation induced by low-dose ADP. These results demonstrate that SZ21-coated HPA-1ab heterozygous PLTs remain functional and able to participate in hemostasis.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SZ21 on the function of HPA-1ab heterozygous PLTs. PLT-rich plasma was obtained from HPA-1ab healthy donors, and the PLT count was adjusted to 3 × 108 per mL with PLT-poor plasma. PLTs were incubated with SZ21, AP2, or an isotype-matched antibody control for 10 minutes at the indicated concentrations. PLT agonists were then added, and the percentage of PLT aggregation was determined using lumiaggregometry. Note that SZ21 has little effect on the extent of PLT aggregation with the exception of low-dose ADP.

Conclusion and Future Aspects

The major finding of this work is that SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments are effective inhibitors of anti-HPA-1a binding and as such are able to efficiently prevent anti-HPA-1a– mediated PLT clearance in vivo, indicating their potential use as a therapeutic agent in preventing anti-HPA-1– mediated NAIT. MoAbs have several potential advantages over currently employed therapies for NAIT, including minimal exposure to multidonor-derived blood products, thus reducing the risk of blood-transmitted diseases. From a logistic point of view, MoAbs can also be less expensive than traditional NAIT treatment options and can be stored for long periods of time before use, making access to such therapeutic agents possible even for outlying hospitals. Furthermore, the mode of action of epitope-specific MoAbs like SZ21 does not rely upon immunosuppression of the maternal or fetal immune system, potentially avoiding side effects such as infection. SZ21 F(ab′)2 should also be able to protect autologous PLTs produced in the fetal marrow from alloantibody-mediated PLT destruction, which may further facilitate correction of fetal neonatal thrombocytopenia. Another potential benefit of SZ21 F(ab′)2 treatment could be through the disassociation of anti-HPA-1a from the surface of the HPA-1a–positive fetal PLTs (Fig. 1C).

A not-uncommon limitation in the use of mouse MoAbs in treating human disease is the potential to develop an immune response to the therapeutic Fab. Although the risk of such a side effect is less likely in neonates, humanization of SZ21 F(ab′)2 would likely be beneficial and/or necessary before undergoing clinical trials in humans.

Finally, there is growing recognition that the conserved fucosylated complex biantennary glycan attached to Asn297 of the heavy chain of IgG contributes importantly to its effector functions, including binding and activation of complement factor C1q and recognition by Fc receptors on white blood cells14-16. Because the glycan attached to Asn297 seems not to be required for the binding of IgG to the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn,15,17 it may be of future interest to evaluate the ability of intravenously administered, deglycosylated SZ21 to bind FcRn, transverse the placenta, and protect the HPA-1a–positive fetal PLTs from clearance by maternally derived anti HPA-1a alloantibodies. Similar strategies might also be effective in preventing passively transferred maternal autoantibodies from mediating destruction of fetal PLTs.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Evaluation of SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments. (A) HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments, and bound antibodies were detected using secondary antibodies specific for either the murine F(ab) (solid lines) or Fc- (dashed lines) regions of IgG. Note that SZ21 F(ab′)2 (green) reacted positively only to the F(ab)-specific secondary antibody, while intact IgG (black) reacted positively to both anti-Fc and anti-F(ab) secondary antibodies, indicating the absence of the Fc- fragment in the F(ab′)2 preparation. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of F(ab′)2 fragments. Two bands with apparent molecular weights (MW) of 27 and 25 kDa, representing the cleaved parts of the heavy and light chains under reducing conditions, are visible with Coomassie Blue staining, demonstrating the purity of the divalent F(ab′)2 fragments of MoAb SZ21 used in this study.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Acknowledgments

TB is a fellow of the German Foundation for Transfusion Medicine and Immunohematology. The technical support of Astrid Giptner and Silke Werth is acknowledged.

This work was supported by Grant HL-44612 (to PJN) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- GP

glycoprotein

- HPA

human platelet-specific alloantigens

- IP

intraperitoneal

- NAIT

neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia

- NOD/SCID

nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient

- PGE1

prostaglandin E1

- RT

room temperature

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Note Added in Proof: While this manuscript was under review, an article by Ghevaert et al. (J. Clin. Invest. 118:2929, 2008) appeared in which a recombinant anti-HPA-1a antibody was used to reduce alloimmune antibody-mediated PLT clearance of murine PLTs expressing a human β3 integrin subunit. The findings of the Ghevaert study entirely support the conclusions of our own study in that both demonstrate the ability to block alloimmune antibody-mediated clearance of PLTs in circulation using an appropriate blocking antibody.

References

- 1.Bussel JB, Primiani A. Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: progress and ongoing debates. Blood Rev. 2008;22:33–52. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller-Eckhardt C, Kiefel V, Grubert A, Kroll H, Weisheit M, Schmidt S, Mueller-Eckhardt G, Santoso S. 348 cases of suspected neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Lancet. 1989;1:363–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91733-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson LM, Hackett G, Rennie J, Palmer CR, Maciver C, Hadfield R, Hughes D, Jobson S, Ouwehand WH. The natural history of fetomaternal alloimmunization to the platelet-specific antigen HPA-1a (PlA1, Zwa) as determined by antenatal screening. Blood. 1998;92:2280–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman PJ, Derbes RS, Aster RH. The human platelet alloantigens, PlA1 and PlA2 are associated with a leucine33/proline33 amino acid polymorphism in membrane glycoprotein IIIa, and are distinguishable by DNA typing. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1778–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI114082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan C. Foetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopaenia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakchoul T, Sachs UJ, Wittekindt B, Sclosser R, Bein G, Santoso S. Treatment of fetomaternal neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia with random platelets. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1293–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xi X, Zhao Y, Jiang H, Wu Q, Li P, Ruan C. Competitive binding of a monoclonal antibody SZ-21 with anti-PlA1 antibodies and its potential for clinical application. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1992;34:239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss EJ, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Grigoryev D, Jin Y, Kickler TS, Bray PF. A monoclonal antibody (SZ21) specific for platelet GPIIIa distinguishes PlA1 from PlA2. Tissue Antigens. 1995;46:374–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1995.tb03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorel N, Brabant S, Christiaens L, Brizard A, Mauco G, Macchi L. A rapid and specific whole blood HPA-1 phenotyping by flow cytometry using two commercialized monoclonal antibodies directed against GP IIIa and GP IIb-IIIa complexes. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:221–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boylan B, Berndt MC, Kahn ML, Newman PJ. Activation-independent, antibody-mediated removal of GPVI from circulating human platelets: development of a novel NOD/SCID mouse model to evaluate the in vivo effectiveness of anti-human platelet agents. Blood. 2006;108:908–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pidard D, Montgomery RR, Bennett JS, Kunicki TJ. Interaction of AP-2, a monoclonal antibody specific for the human platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex, with intact platelets. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12582–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boylan B, Chen H, Rathore V, Paddock C, Salacz M, Friedman KD, Curtis BR, Stapleton MA, Newman DK, Kahn ML, Newman PJ. Anti-GPVI-associated ITP: an acquired platelet disorder caused by autoantibody-mediated clearance of the GPVI/FcRγ-chain complex from the human platelet surface. Blood. 2004;104:1350–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An G, Dong N, Shao B, Zhu M, Ruan C. Expression and characterization of the ScFv fragment of antiplatelet GPIIIa monoclonal antibody SZ-21. Thromb Res. 2002;105:331–7. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(02)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:21–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collin M, Shannon O, Bjorck L. IgG glycan hydrolysis by a bacterial enzyme as a therapy against autoimmune conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4265–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711271105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin WL, West AP, Jr, Gan L, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure at 2.8 A of an FcRn/heterodimeric Fc complex: mechanism of pH-dependent binding. Mol Cell. 2001;7:867–77. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Evaluation of SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments. (A) HPA-1ab PLTs were incubated with SZ21 F(ab′)2 fragments, and bound antibodies were detected using secondary antibodies specific for either the murine F(ab) (solid lines) or Fc- (dashed lines) regions of IgG. Note that SZ21 F(ab′)2 (green) reacted positively only to the F(ab)-specific secondary antibody, while intact IgG (black) reacted positively to both anti-Fc and anti-F(ab) secondary antibodies, indicating the absence of the Fc- fragment in the F(ab′)2 preparation. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of F(ab′)2 fragments. Two bands with apparent molecular weights (MW) of 27 and 25 kDa, representing the cleaved parts of the heavy and light chains under reducing conditions, are visible with Coomassie Blue staining, demonstrating the purity of the divalent F(ab′)2 fragments of MoAb SZ21 used in this study.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.