Abstract

Background: Patient’s rights are worldwide considerations. Saudi Patient’s Bill of Rights (PBR) which was established in 2006 contained 12 items. Lack of knowledge regarding the Saudi PBR limits its implementation in health facilities. This study aimed to investigate the knowledge of health professions’ students at College of Applied Medical Sciences (CAMS) Riyadh Saudi Arabia regarding the existence and content of Saudi PBR as well as their attitude toward its ineffectiveness.

Methods: A 3-parts survey was used to collect data from 239 volunteer students participated in the study. Data were analyzed by descriptive and analytical statistics using SPSS.

Results: Results showed that although the majority of students (96.7%) believe in the ineffectiveness of patient’s rights, half (52.3%) of them had perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of Saudi PBR and only 7.9% of them were knowledgeable about some items (1–4 items) of the bill. Privacy and confidentiality of patient was the most common known patient’s rights. Students’ academic level was not correlated to neither their knowledge regarding the bill existence or its content nor to their attitude toward the bill. The majority of the students (93%) reported that only one course within their curriculum was patient’s rights-course related. About one quarter (23.4%) of the students reported that teaching staff used to mention patient’s rights in their teaching sessions.

Conclusion: The Saudi health professions students at CAMS have positive attitude toward the ineffectiveness of patient’s rights nevertheless they showed limited knowledge regarding the existence of Saudi PBR and its contents. CAMS curriculums do not support the subject of patient’s rights.

Keywords: Patient’s Rights, Saudi Patient’s Bill of Rights (PBR), Knowledge, Attitude, Bioethics, Saudi Health Profession Program Curriculum, Saudi Health Professions Student

Introduction

Deliberating the Patient’s Bill of Rights (PBR) is one of the major human ethical and legal principles (1). Since the introduction of the human rights by the United Nations in 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) generated PBR as part of the human rights and legislations on PBR have been passed all over the world (2,3). The PBR are listed guarantees for those receiving medical care (3) emphasizing on care and treatment rights (1). The PBR are generated to ensure the ethical treatment of all patients, to help patients feel more confident in the healthcare system, to assure that the healthcare system is fair and it works to meet patients’ needs, to encourage patients to take an active role in staying or getting healthy, to stress the importance of a strong relationship between patients and their healthcare providers, and to provide high quality healthcare (3–6). On the other hand, lack of respect to PBR may lead to hazards for security and health situation of patients, may decreases efficiency, effectiveness, and suitable care of patients (3). Patient’s rights vary in different countries often depending upon prevailing cultural and social norms but there is growing international consensus that they include privacy, confidentiality of medical information, treatment refusal, proper information on healthcare services, consultation on medical emergencies, and acknowledgment of relevant risk of medical procedures (1–3). They may take the form of a law or a non-binding declaration (3,4). In 2006, the Saudi Ministry of Health defined the patient’s rights as the policies and rules that must be preserved and protected by the health facility toward patients and their families and it declared the PBR (6,7). The Saudi PBR is composed of 12 items related to knowing patient and family rights and responsibilities, getting healthcare, privacy and confidentiality, safety and protection, respect and appreciation, participation in healthcare plan, treatment refusal, participation in research study, organ and tissue donation, health insurance and financial policies, clear and comprehensive declaration forms, and complains and suggestions policies and procedures (7–10). The objectives of PBR are very noble but its success will depend greatly on how healthcare providers know about it and how well it is implemented. Unfortunately, little is known about the implementation of the PBR in Saudi Arabia (6). Before the PBR implementation by healthcare providers, the health professions’ students should be knowledgeable about the existence and content of the bill and have positive attitude toward its importance. This study aimed to investigate the knowledge of health professions’ students at College of Applied Medical Sciences (CAMS) Riyadh, Saudi Arabia regarding the existence and content of Saudi PBR as well as their attitude toward its ineffectiveness.

Materials and methods

The present descriptive-analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted on female section of CAMS, King Saud University. CAMS includes 6 departments offering health professions programs as rehabilitation health sciences, radiological sciences, and laboratory skills sciences. These programs are offered through 9 educational levels. The first 2 levels are university requirement levels while the 3rd level is college core level. The student joins her health profession program from the 4th level. Data gathering tool was a questionnaire designed by authors and based on the Saudi PBR as well as on the literature (1,4–6,8). The questionnaire is categorized in 3 parts; the first part contained the demographic information including the student’s department, program, and educational level. The second part is about the students’ knowledge regarding the existence and contents (12 items) of the Saudi PBR and their attitude toward its importance. The third part is about the inclusion of PBR within the program curriculum. The questionnaire included closed-ended questions with three-point scale for student’s perceived responses. The three points are “Yes”, “to some extend”, and “No”. The three points were coded as following; yes= 2, to some extended= 1, and no= 0. In addition the students were asked to list as many items as they recognize from the 12 items of Saudi PBR. Moreover, they were asked about the existence of courses that are designed for or include topics related to the PBR. All necessary approvals for the study were obtained from CAMS vice dean, no additional review or approval is required at the college. Convenient sampling was applied to enroll students into the study. Inclusion criteria included registration of the students in level 4 or higher, agreement of the students to participate in the study, and completion of the questionnaire. Out of the 831 registered students during the academic year 2011–2, 600 (72.2%) were at level 4 or higher, 400 (48.1%) of them agreed to participate and 239 (28.8%) of them completed the questionnaire and participated in the study. Students were informed of the study aim, ensured that questionnaire is anonymous, and assured that their participation is voluntary with no consequences at all for non-participation. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 descriptive analysis, Chi-Square test, and two-tailed Spearman correlation test were used. A P< 0.05 level was considered statistically significant.

Results

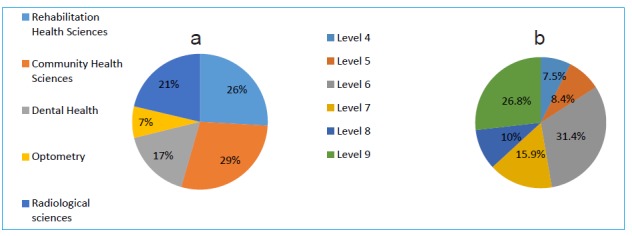

Out of the 831 students enrolled in CAMS at the academic year 2011–2, 239 students were eligible to participate in the study with a response rate of 28.8%. The frequency distribution of participating students from each department and each level are presented in Figure 1a and Figure 1b .

Figure 1 .

a) Frequency distribution of participating students’ departments (N= 239). b) Frequency distribution of participating students’ academic level (N= 239).

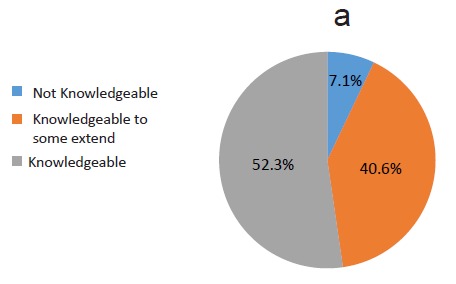

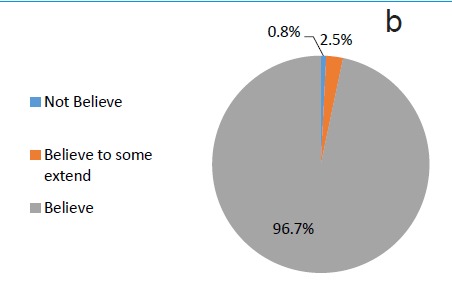

Junior students (levels 4–6) were 47.3% while senior students (levels 7–9) were 52.7%. About half (52.3%) of the students perceived that they are knowledgeable regarding the existence of Saudi PBR (Figure 2a). Meanwhile, the majority of students (96.7%) showed perceived believe in the importance of patient’s rights (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

a) Level of perceptual CAMS students’ knowledge about the existence of the Saudi PBR (N= 239). b) Levels of perceptual CAMS students’ attitude regarding the importance of PBR (N= 239).

a) .

b) .

Only 7.9% of the students were knowledgeable about some items (1–4 items) of the 12 items of Saudi PBR (Table 1). Out of the 19 students knowledgeable about the items of Saudi PBR, 13 of them were knowledgeable about the patient’s privacy and confidentiality and 9 of them were knowledgeable about patient’s right of getting healthcare (Table 2).

Table 1 . Frequency distribution of CAMS students who are knowledgeable about items of the Saudi PBR.

| Level of knowledge | Frequency | Percent |

| Knowledgeable about no items | 220 | 92.1 |

| Knowledgeable about one item | 5 | 2.1 |

| Knowledgeable about two items | 7 | 2.9 |

| Knowledgeable about three items | 5 | 2.1 |

| Knowledgeable about four items | 2 | 0.8 |

| Knowledgeable about 12 items | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 239 | 100 |

Table 2 . Frequency distribution of CAMS students and the known Items of Saudi PBR.

| Patient’s Right | Frequency | Percent |

| Knowing patient and family rights and responsibilities (patient’s bill of right # 1) | 4 | 1.7 |

| Getting healthcare (patient’s bill of right # 2) | 9 | 3.8 |

| Privacy and confidentiality (patient’s bill of right # 3) | 13 | 5.4 |

| Safety and protection (patient’s bill of right # 4) | 5 | 2.1 |

| Respect and appreciation (patient’s bill of right # 5) | 4 | 1.7 |

| Participation in healthcare plane (patient’s bill of right # 6) | 5 | 2.1 |

| Refuse treatment (patient’s bill of right # 7) | 2 | 0.8 |

| Health insurance and financial policy (patient’s bill of right # 10) | 1 | 0.4 |

Chi-Square test showed no significant association (P= 0.234) between the students’ perceptual knowledge of PBR existence and their level of knowledge of the 12 Saudi items of PBR but there was significant association (P= 0.001) between the students’ perceptual knowledge of PBR existence and their perceptual believe regarding the importance of PBR (Table 3).

Table 3 . Association between CAMS students’ perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of Saudi PBR and levels of their perceptual believe regarding importance of bill.

| Level of perceptual knowledge about the Saudi PBR existence | Level of perceptual believe regarding importance of patient rights | |||

| Not believe | Believe to some extend | Believe | Total | |

| Not knowledgeable | 2 | 1 | 14 | 17 |

| Knowledgeable to some extend | 0 | 3 | 94 | 97 |

| Knowledgeable | 0 | 2 | 123 | 125 |

| Total | 2 | 6 | 231 | 239 |

P= 0.001

Two-tailed Spearman correlation showed that there was a significant (P= 0.023) relation between the department and level of students’ perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of PBR (Table 4). Radiological sciences and optometry departments had the highest level of student’s perceptual knowledge. There were no significant correlations between the department and students’ perceptual attitude toward the importance of patient’s rights, students’ level of knowledge about the Saudi 12 items of PBR, or number of known items from the Saudi 12 items of PBR (P= 0.081, 0.752, and 0.721 respectively).

Table 4 . Correlation between the CAMS department and students’ perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of Saudi PBR.

| Items | r s | P |

| Department | 0.147* | 0.023 |

| Students' perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of PBR |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.050 level (2-tailed).

Academic level had no significant correlations with any of the following variables; students’ perceptual knowledge regarding the existence of PBR (P= 0.118), students’ perceptual attitude about the PBR importance (P= 0.893), students’ level of knowledge about the Saudi 12 items of PBR (P= 0.979), or number of recognized items from the Saudi 12 items of PBR (P= 0.948)

Students who reported that their curriculums included patient’s rights-course related were 14 (6%) students. They were almost equally distrusted among the community health sciences (21%), dental health (29%), optometry (29%), and radiological sciences (21%) departments. More than half (57%) of them were senior students. The majority of them (93%) reported that the number of patient’s rights-course related is only one course.

Very minor number (5.2.1%) of students reported that there were patient’s rights topics-related in their courses’ specifications. About one quarter (23.4%) of the students reported that although there were no patient’s rights-course related courses in their curriculums nor there were no patient’s rights topics-related in their courses’ specifications, the teaching staff used to mention patient’s rights in their teaching sessions.

Students reported that teaching staff mentioned patients’ rights in one to three courses. These courses were taught before, during, or after they started their clinical practice. These courses are mainly combined courses which included theoretical and clinical topics. Lecturers are the more frequent teaching staff who were mentioning patient’s rights during their classes.

Discussion

Results of the current study indicated that the majority (96.7%) of the CAMS health professions’ students believe in the importance of patient’s rights. Believe was mainly based on ethical and conscience issues more than knowledge. This is particularly true because only about half (52.3%) of the students were knowledgeable about the existence of Saudi PBR and very few of them (19 students, 7.9%) were able to recognize some items (1–3) of the bill. The Saudi healthcare providers’ knowledge about the existence of Saudi PBR was not better than the students’ knowledge. In the survey done by Alghanim on 242 Saudi physicians and nurses only 66.1% of them knew about the existence of the PBR and about half (48.8%) of those knew about PBR had “little or very little” knowledge about the bill contents (6). The few studies which included students had very similar situation to the Saudi students. Example is the results of survey-based study included 270 Iranian medical and paramedical students, in which 53% of the students were familiar with the patient’s rights (5). In another Iranian survey, the percentage of students knowledge about the Iranian patient’s rights charter were varied from poor (35.6%), moderate (27.7%) to good knowledge (36.7%) (11).

In the current study, the Saudi PBR number three, privacy and confidentiality was the most popular and known among the Saudi students. Out of the 19 students who were knowledgeable about the bill content, 13 of them listed privacy and confidentiality. Similarly the study of Alghanim showed that the patient’s respect, privacy, and confidentiality were the patient’s rights with high score by the Saudi healthcare providers (6). Religious and culture issues could explain this result. Saudi students are Muslims with conservative culture. Qur’an and Sunnah as the Islamic resources had emphasized on confidentiality as important and shared human value. In Islam healthcare providers are obligated to protect the confidential information of their clients (12). The Saudi conservative culture is known to stress on privacy especially for patients. That is why there was no association between students’ knowledge of Saudi PBR existence and their knowledge about its contents. Students may not be aware of the bill existence but by their cultural and moral background they perceived that keeping patients’ privacy and saving their information confidential are patient’s rights.

Saudi students showed no significant correlation between their academic level and their knowledge about the existence of the Saudi PBR or its content. The same was applied about their attitude toward the importance of the bill. The Iranian medical and paramedical students showed similar results; they showed no significant correlation between the student’s age and awareness about the patient’s rights (5). This result empowers the authors’ claimed theory of moral basis of Saudi students’ knowledge and attitude regarding the PBR. If the students’ knowledge regarding the content of the bill was related to the knowledge they get from their curriculum and programs; the students would show increase in their knowledge from junior or pre-clinical educational levels to the senior or clinical levels. Their attitude toward the importance of the bill would also increase as they engage more in the clinical practice and encounter patients in the higher educational levels but this was not the case in the current study.

Educational health professional department was not correlated with the Saudi students’ attitude toward the importance of patient’s rights or the students’ knowledge regarding the Saudi PBR 12 items. On the other hand, the department type was correlated with the students’ knowledge regarding the existence of the Saudi PBR as the students of radiological sciences and optometry departments had the highest level of knowledge. This might be explained by the fact that these two departments were among the short listed departments in which students reported that they had patient’s rights-course related. Through this course they might had tackle the concept of patient’s rights. The nature of radiological sciences department and the hazardous of radiology procedures might gave the students the chance to get close to patient’s considerations as patient’s safety and patient’s rights. It was observed also that the majority (82.2%) of optometry department students were senior students which would allow them to cover most of the curriculum and to expose most of the courses so they reported that one course was related to the concept of patient’s rights.

In general, the current curriculums of CAMS programs are not supporting the students’ knowledge regarding the patient’s rights to the satisfactory level. Majority of the students reported that there is no specific course dedicated to patient’s rights (94%) and patient’s rights are not a topic in their courses’ specifications (97.9%). Only about one quarter (23.4%) of the students reported that their teaching staff mention patient’s rights during their teaching sessions. It looks like the students encountered the medical ethics and patient’s rights in an accidental subjective approach within their programs according to the point of view of their teaching staff. How much the teaching staff are knowledgeable about patient’s rights and how is their attitude toward it would affect the delivered amount and type of information regarding patient’s rights to their students. The current study may subject to the challenge of being survey-based study in which the results are dependent on the perceived and reported data gathered from students. But the great agreement between the students’ perception and report regarding the situation of their curriculum reduces this challenge. Conducting observational study with interviewing students and teaching staff might be valuable for overcoming the above mentioned limitation of survey-based study.

Another clue that there is shortage in CAMS curriculums’ planning is that the courses in which the students reported that teaching staff mention the patient’s rights were taught before, during or after the on-site clinical practice. If the patient’s rights topic was intentionally implanted in the curriculum, it would be designed as pre-request or co-request to the clinical practice courses which is not the CAMS’ case. The most frequent teaching staff who mention the patient’s rights topics in their courses are the lecturers (MSc. holders). This may be due to the fact that lectures are mostly got their masters degrees from Western Universities in which the patient’s rights, professionalism and medical ethics are well established subjects in the under graduate and post graduate programs. Most properly the lecturers’ resources for the patient’s rights topics are their maters programs references and not the Saudi PBR.

The lack of knowledge about the bill among the Saudi healthcare providers recorded by Alghanim and said to be the main obstacle that limited the Saudi physicians and nurses to implement PBR (6) appears to be applicable as well to the Saudi students as proved by the current study results. The authors echo the deceleration of World Medical Association (WMA)in 1999 (13) that the topics of medical ethics and patient’s rights should be included in the curriculum of medical and health professions schools worldwide. Furthermore, it should be included in continuing education programs at both graduate and postgraduate programs (4). Teaching staff, as a role model, behavior with patients during clinical practice sessions is a hidden curriculum that can enhance the students’ knowledge regarding patient’s rights and can also develop a positive attitude toward it.

In conclusion, although the Saudi health professions students at CAMS have positive attitude toward the importance of patient’s rights they showed very limited knowledge regarding the existence of Saudi PBR and its contents. Respecting patient’s privacy and keeping the confidentiality are the most popular patient’s rights among the Saudi students. CAMS curriculums do not support the subject of patient’s rights.

Redesign the CAMS curriculums are highly recommended to carefully implant the patient’s rights within a course of the curriculum in the suitable academic level particularly pre-request to the clinical practice courses. Re-do this study to investigate the effect of curriculum reconstruction. Use of observational design and qualitative approach with structured or semi structured interview and including both students and teaching staff would also enrich this recommended study. Conducting the study in more different cities than Riyadh would introduce clearer picture about the Saudi situation.

Ethical issues

The study proposal was approved by the college vice dean. Students were voluntarily participating in the study with no any negative consequences to those who did not participate.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SBE and AA initiated the study idea. All authors participated in data collection and reviewing literature. SBE treated the collected data statistically and wrote the manuscript.

Authors’ affiliations

1Department of Rehabilitation Health Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 2Department of Community Health Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Saudi health colleges are encouraged to assess their students’ knowledge and attitude regarding the PBR. This would help them to plan remedy actions for curriculum development in a way to support the patient’s rights.

Policy-makers at the ministry of higher education along with ministry of health are recommended to ask all health programs to offer a mandatory course that covers the health professions’ ethics including Patient’s Bill of Rights (PBR). This course could be offered in the programs preclinical levels.

Implications for public

Patients are seeking qualified health services and implementation of Patient’s Bill of Rights (PBR) by the healthcare providers. Today’s students are tomorrow’s healthcare providers. Introducing the PBR in the health professions’ programs would assure future healthcare providers who are knowledgeable about the PBR, have positive attitude toward it, and are able to implement it.

Citation: El-Sobkey SB, Almoajel AM, Al-Muammar MN. Knowledge and attitude of Saudi health professions’ students regarding patient’s bill of rights. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 3: 117–122. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.73

References

- 1.Tabei SZ, Azar MR, Mahmoodian F, Mohammadi N, Farhadpour H, Ghahramani Y. et al. Investigation of the Awareness of the Students of Shiraz Dental School Concerning the Patients’ Rights and the Principles of Ethics in Dentistry. J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Scien. 2013;14:20–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Patient rights [internet]. [cited 2013 December 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/genomics/public/patientrights/en/

- 3.Mastaneh Z, Mouseli L. Patients’ Awareness of Their Rights: Insight from a Developing Country. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1:143–6. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakan O, Ozgür C, Ergönen AA, Onder M, Meral D. Midwives and nurses awareness of patients’ rights. Midwifery. 2009;25:756–65. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghodsi Z, Hojjatoleslami S. Knowledge of students about Patient Rights and its relationship with some factors in Iran. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;31:345. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alghanim SA. Assessing knowledge of the patient bill of rights in central Saudi Arabia: a survey of primary health care providers and recipients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:151–5. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of health portal. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Health tips: Patient’s Bill of Rights and responsibilities [internet]. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/healthawarness/educationalcontent/healthtips/pages/tips-2011-1-29-001.aspx

- 8.Almoajel AM. Hospitalized patients awareness of their rights in Saudi governmental hospitals. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research. 2012;11:329–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saleh HA, Khereldeen MM. Physicians’ perception towards patients’ rights in two governmental hospitals in Mecca, KSA. Int J Pure Appl Sci Technol. 2013;17:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habib FM, Al-Siber HS. Assessment of awareness and source of information of patients’ rights: a cross-sectional survey in Riyadh Saudi Arabia. American Journal of Research Communication. 2013;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranjbar M, Samiehzargar A, Dehghani A. Evaluation of clinical training of students in teaching hospitals of Yazd Patient Rights. Journal on Medical Ethics, Special Patient Rights. 2010;3:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alahmad G, Dierickx K. What do Islamic institutional fatwas say about medical and research confidentiality and breach confidentiality? Dev World Bioeth. 2012;12:104–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peeling RW, Saxena A. Books & Electronic MediaMedical Ethics Manual. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:159–60. [Google Scholar]