Abstract

Background

Limited data are available on interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviors and increase knowledge of HIV vaccine trial concepts in high risk populations eligible to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials.

Methods

The UNITY Study was a two-arm randomized trial to determine the efficacy of enhanced HIV risk reduction and vaccine trial education interventions to reduce the occurrence of unprotected vaginal sex acts and increase HIV vaccine trial knowledge among 311 HIV-negative non-injection drug using women. The enhanced vaccine education intervention using pictures along with application vignettes and enhanced risk reduction counseling consisting of three one-on-one counseling sessions were compared to standard conditions. Follow-up visits at one week and one, six and twelve months after randomization included HIV testing and assessment of outcomes.

Results

During follow up, the percent of women reporting sexual risk behaviors declined significantly, but did not differ significantly by study arm. Knowledge of HIV vaccine trial concepts significantly increased but did not significantly differ by study arm. Concepts about HIV vaccine trials not adequately addressed by either condition included those related to testing a vaccine for both efficacy and safety, guarantees about participation in future vaccine trials, assurances of safety, medical care, and assumptions about any protective effect of a test vaccine.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to boost educational efforts and strengthen risk reduction counseling among high-risk non-injection drug using women.

Keywords: HIV, vaccines, behavioral intervention, women, substance use

In 2006, more than 56,000 new HIV infections occurred in the United States1. Women comprised 27% of new HIV diagnoses, with 80% of these attributed to high-risk heterosexual contact2. Black and Latino women had the highest incidence of infection attributed to heterosexual transmission2. Although early in the epidemic injection drug use emerged as a risk factor for women, the role of non-injection drug use in heterosexual HIV risk among women is increasingly important. Non-injection drug use, including crack cocaine and inhaled heroin and cocaine, has been associated with higher HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviors, such as unprotected sex, increased number of partners and exchange of sex for drugs and money3–5.

A preventive HIV vaccine is one biomedical prevention strategy being developed and tested among populations at risk. While significant challenges exist in the search for a safe and effective HIV vaccine6, an important part of the discovery process is testing in humans for safety and immunogenicity, as well as for efficacy. To measure vaccine efficacy, trials of HIV vaccines must be conducted among participants who are at high risk for acquiring HIV. At the same time, it is ethically imperative that efficacy trials also include HIV risk reduction counseling to help reduce risk behaviors and behavioral disinhibition, i.e., increases in risk behavior based on assumption of receiving vaccine rather than placebo or misplaced assumptions about any protective effect of the vaccine being studied7;8. However, there is no general agreement on the type of behavioral risk reduction counseling that could be effective in conjunction with an HIV vaccine efficacy trial9.

Most behavioral HIV risk reduction interventions shown to be effective in reducing sexual risk among at-risk women have been group-based and multi-session10;11. These intervention characteristics may make integration into vaccine trials challenging as, ideally, HIV risk reduction counseling within the context of a vaccine trial (with study visits that are often long due to the extent of study procedures) would be a series of brief, one-on-one intervention sessions designed to be delivered concurrently with a vaccine schedule. Effective behavioral interventions for populations, including non-injection drug using women, that can be delivered within the context of a vaccine trial have yet to be tested.

Another important issue for HIV vaccine efficacy trials is ensuring that participants are knowledgeable about HIV vaccines and trial conduct so that they may make informed choices about participating. In addition to concepts related to any research participation (e.g., purpose of trial, what is expected, risks and benefits, alternatives to trial participation, ability to withdraw)12, there are several concepts important to the conduct of vaccine efficacy trials, such as placebo, blinding, randomization, vaccine-induced seropositivity, the potential for social harms and the possibility of adverse events13–15. Previous studies indicate that women who were non-injection drug users had the lowest levels of knowledge about HIV vaccine trial concepts compared to other at-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug users15;16. With ongoing education, vaccine knowledge among the women who were non-injection drug users increased, but was still below the knowledge levels of MSM16. A limited number of studies have been conducted to examine education about HIV vaccine trials in the context of the informed consent process17–20. New modalities for vaccine education and the informed consent process are particularly relevant for conducting vaccine trials with participants characterized by poverty, low education and unfamiliarity with the research process21.

The UNITY Study was a two-arm randomized trial to determine the efficacy of enhanced HIV risk reduction and vaccine trial education interventions to 1) reduce the occurrence of unprotected vaginal sex acts; and 2) increase HIV vaccine trial knowledge among HIV-negative, high-risk non-injection drug using women. This paper presents the trial design, baseline characteristics of participants, and primary study outcomes of the UNITY Study.

METHODS

Study population

From March 2005 to June 2006, women in New York City (predominately in the South Bronx area) were recruited for the UNITY Study through street outreach by trained outreach workers; flyers distributed in the neighborhood; and referrals from community agencies, clinics, and participants in current and previous studies. The goal of the recruitment and eligibility criteria was to recruit women who would be similar to those who would be recruited for an HIV vaccine trial focused on preventing sexual transmission of HIV, rather than a representative or generalizable sample. The criteria also excluded women who had a recent history of injection drug use since most HIV vaccines under development are being tested for sexual rather than parenteral exposure. Thus, we used the following eligibility criteria: tested HIV antibody negative by the study; 18 years of age or older; reported non-injection use of heroin, cocaine or crack cocaine in the previous six months; no reported injection drug use in the previous 3 years; at least one instance of vaginal sex without a condom in the previous three months; and not currently pregnant with no intent to become pregnant in the next 12 months. Eligibility was determined by interviewer-administered questions22. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the New York Blood Center and The New York Academy of Medicine.

Screening visit

After informed consent for screening was obtained, audio-computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) was used to collect data, including demographic characteristics, sexual behaviors, alcohol and drug use, reproductive history, depression, potential for domestic violence, childhood abuse and attitudes about safer sex. Data were also collected on knowledge about HIV vaccine trials, willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials and barriers and motivators to participating in such trials. Following baseline data collection, participants received HIV and hepatitis B pre-test counseling and education. Blood specimens were collected and tested for HIV antibody and markers of HBV infection22.

Randomization

Approximately two weeks after screening, participants received their HIV and HBV marker test results and post-test counseling. Participants with positive test results were referred for medical and social services. Women who were negative for HIV antibodies were invited to enroll in the trial. Enrolled women who were found to be susceptible to HBV infection by serologic testing were offered hepatitis B vaccine to be administered at that visit, with subsequent doses at one and six months later.

The study statistician (DRH) generated the allocation sequence to randomize participants to enhanced or standard intervention in a 1:1 ratio, using block sizes of 6 and 4. From these lists, opaque, sealed envelopes were prepared and kept in a locked file with access only by the project coordinator (DL). Participant eligibility and consent were verified before the assignment was revealed.

Enhanced and standard conditions

To inform the development of the materials for the enhanced conditions, four focus groups were conducted among women who met the study eligibility criteria to explore HIV vaccine trial concepts and sexual risks23. Two groups were held among African American women and two among Latina women. The women’s perceptions and understanding about the following vaccine trial concepts were explored: how vaccines affect the immune system, how vaccines are developed, vaccine trial concepts, risks and benefits of participating in a trial, and importance of following the protocol of a vaccine trial. For sexual risk reduction, the groups discussed sexual relationships, characteristics of close relationships, self-perception of HIV risk, meaning of condoms and condom negotiation skills.

The intervention materials and ACASI assessment were piloted among women from the target population and based on the results of the pilot, we refined the intervention materials, redesigned parts of the ACASI assessment and repeated the pilot. Women who participated in the focus groups and pilot were not eligible for the trial.

In the trial, all materials on vaccine trial concepts were introduced to the participants at the randomization visit and reviewed one week later. Sexual risk reduction counseling occurred at randomization and at 1-month and 6-month visits. All manuals are available from the principal investigator (BAK).

Enhanced HIV vaccine education

Education on vaccine trial concepts was adapted from the combined work of Coletti et al.17 and Murphy et al20. The vaccine trial concepts included basics of how vaccines are made and how they work, the purpose of vaccine trials, vaccine-induced seropositivity, placebo, randomization, blinding, and procedures involved in a vaccine trial. These concepts were presented using standardized flipcharts with pictures and diagrams. Interspersed in the presentation were “application vignettes” that encouraged the participant to cognitively process the information by applying it to a what-if situation. For example, randomization was described as “like flipping a coin” and “nobody knows in advance whether the coin will fall heads up or tails up”, followed by two questions: “What would you say to a friend who told you, ‘You can choose which group you are in.’ and ‘I’m high risk so there is a good chance I’ll get into the group that gets the experimental vaccine.’?”. Besides engaging the participants to process the information, these vignettes allowed the counselor to assess the participant’s comprehension and correct errors. A 7-minute video that included testimonials by a number of women who had participated in vaccine trials was then presented. The first session ended with the counselor giving the participant a sample consent form which was illustrated with the drawings from the flipchart to cue recall of the information that had just been presented. Participants returned one week later and met with the counselor to revisit vaccine trial concepts and receive answers to any further questions they may have had.

Standard HIV vaccine education

The standard vaccine education condition was based on the two-session informed consent process outlined by Coletti et al17. Content included definitions of placebo, randomization and blinding, information about vaccine trial procedures, plus discussion of risks (e.g., vaccine-induced seropositivity) and benefits of participating in an HIV vaccine trial.

Enhanced risk reduction counseling

The enhanced counseling arm was informed by Social Cognitive Theory24 and the intervention was designed to help participants deal with their social environment (e.g., partner’s behavior, drug use), optimize personal processes (e.g., self-efficacy, intention), and develop behavioral strategies (e.g., negotiation skills, condom use) to reduce sexual risk. The first session at the enrollment visit began with a five minute video that showed women at different stages of readiness to reduce risk. Its purposes were to heighten risk sensitization, foreshadow the topics to be covered, normalize various stages of readiness for prevention behavior, assist the counselor in rapidly identifying existing beliefs that impede the participant from reducing risk, and model how women successfully initiate safer-sex strategies within their own relationships. After the video, the counselor identified the participant’s individual pattern of risk through asking the participant a series of standardized questions about her sexual behavior with steady partners, exchange partners, and casual partners; the level of risk she associated with those behaviors; and her rationale for engaging in risk. Strategies for reducing risk were tailored to the participant’s behavior, including substance use, and beliefs about HIV transmission and delivered using flip-charts and application vignettes. For example, if the participant said that using condoms with her steady partner would imply lack of trust, the counselor used seatbelts as an analogy to differentiate between protection and trust, and followed up by asking, “What are some things you can do to help your steady guy see condoms as simple protection and not as a big issue of trust?” A number of strategies were offered to reduce HIV risk related to drug use and trading sex. Following this was a demonstration of how to apply male and female condoms; questions, answers and suggestions for how to introduce condom use to one’s partner; and a participant-initiated personal risk reduction plan.

The second counseling session, conducted one month after the first, began with a review of progress toward the participant-initiated risk reduction plan for using male and female condoms. The counselor addressed misunderstandings that impede condom use through an exercise in which the participant created a sexual encounter scenario by selecting among cards that depicted partner types, types of sex and reason for sex. The counselor asked if the encounter was risky, and corrected mistakes with educational messages that emphasized that risk is associated with sexual behavior rather than reason for sex. At the third and final counseling session, participants watched the video they had viewed at the first session and discussed whether they related to a different woman than they had identified with at the first session. The prior session’s risk reduction goals were reviewed and a short problem-solving exercise engaged the participant to identify her successful strategies for safer sex and obstacles to full adherence to those strategies.

Standard risk reduction counseling

Participants assigned to the control condition received a three-session HIV counseling and testing program, based upon the Project RESPECT model25.

Enhanced and standard arm sessions were conducted by experienced HIV counselors who completed four hours of training in the study intervention materials. Sessions were audio-taped and a planned 10% random sample of tapes was selected for review by raters at The New York Academy of Medicine (ML, SB). The sessions were scored on numerous items specific to the session. The quality assurance (QA) scores were percentages of the total possible score and sessions with scores above 80% were considered to follow the protocol and therefore, acceptable. Regular feedback was provided to the counselors during the study.

Follow-up visits and collection of outcome data

In order to mimic a typical schedule of a vaccine trial and to correspond to the standard vaccination schedule for hepatitis B vaccine26, follow-up visits were scheduled at one week, and one, six and twelve months after randomization for all women. At these visits, participants completed a follow-up survey by ACASI technology prior to any enhanced or standard intervention materials. Blood specimens were collected for testing for HIV antibody testing.

HIV antibodies were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA). Sera that were reactive on first testing were re-tested in duplicate. Repeatedly reactive samples were confirmed by Western blot assay. Participants with a positive test result at any follow-up visit were referred for medical and social services.

Measures

For these analyses, a subset of measures was used as described below.

Demographic characteristics

These variables included age, race/ethnicity, place of birth, years of education, employment and income, health insurance, usual living situation, incarceration history and staying overnight in a shelter or group home, jail, drug treatment or on the street at least once in the past year. Since the age distribution was skewed to older ages (only 8.8% were 30 years of age or less), age groups were constructed by subdividing the sample approximately into thirds (18–40, 41–45 and 46+ years).

HIV vaccine trial knowledge measures

Adapted from previous studies of HIV vaccine trial knowledge15, participants were asked 18 knowledge questions about HIV vaccine trials for which they could respond “agree” (the statement was true), “disagree” (the statement was false) or “not sure” (e.g., “In a vaccine study, the study nurse will decide who gets the real vaccine and who gets the placebo.”).

Sexual risk behavior measures

Participants were asked about three types of male partners with whom they had vaginal or anal intercourse in the previous 3 months: steady partner (a man you had sex with that you feel closest to in your heart), exchange partners (men you had sex with who gave you money or drugs or other services for having sex with them) and casual partners (non-steady and non-exchange partners). For each type of partner, participants were asked about numbers of times they had had vaginal and anal intercourse and number of times a condom was used. Unprotected vaginal or anal sex was defined as not using a condom at least once for that activity. We also calculated the log transformed Vaginal Episode Equivalent (VEE) which is the sum of all unprotected vaginal sex episodes + 2*number of anal sex episodes + 0.1*number of unprotected oral sex activities27.

Substance use measures

Participants were asked the frequency of non-injection use of specific drugs in the previous three months on a seven-point scale (never to every day). The drugs included in these analyses were crack cocaine, cocaine, and non-injection heroin. Alcohol use was defined as none, light use (3 or less drinks/day on no more than 1–2 days per week), moderate use (4–5 drinks per day on no more than 1–2 days per week or 1–5 drinks per day on 3–6 days per week or 1–3 drinks per day on a daily basis) or heavy use (4 or more drinks every day or 6 or more drinks on a typical day when drinking)28.

Statistical analysis

This study was originally planned to have 180 subjects in each arm which, based on the outcome measures of HIV vaccine knowledge and VEE, would have 80 percent power to detect an effect size (ratio of mean treatment arm differences / standard deviation) of 0.30 with a two sided t-test with alpha=0.05. However, with the 154 subjects in the intervention arm and 157 subjects in the standard arm, the study still had 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.32.

Intent-to-treat comparisons were made between the participants randomized to the enhanced arm and those to the standard arm. The percent of women reporting unprotected vaginal sex at each study visit was compared using contingency tables and exact tests. For the HIV vaccine knowledge outcome, we calculated the mean number of items correct on the knowledge questions. The mean log VEE and the mean number of items correct at each study visit were compared by study arm using t-tests.

For the total study sample combined, changes in the proportion of women reporting unprotected sex between study visits was compared using McNemar’s discordant pair analysis. Changes in the mean number of vaccine knowledge items correct between study visits was compared using paired t-tests. In addition, the proportion of women correctly identifying each knowledge item was calculated and the proportion correct for each item between study visits was compared using McNemar’s discordant pair analysis.

RESULTS

Study population

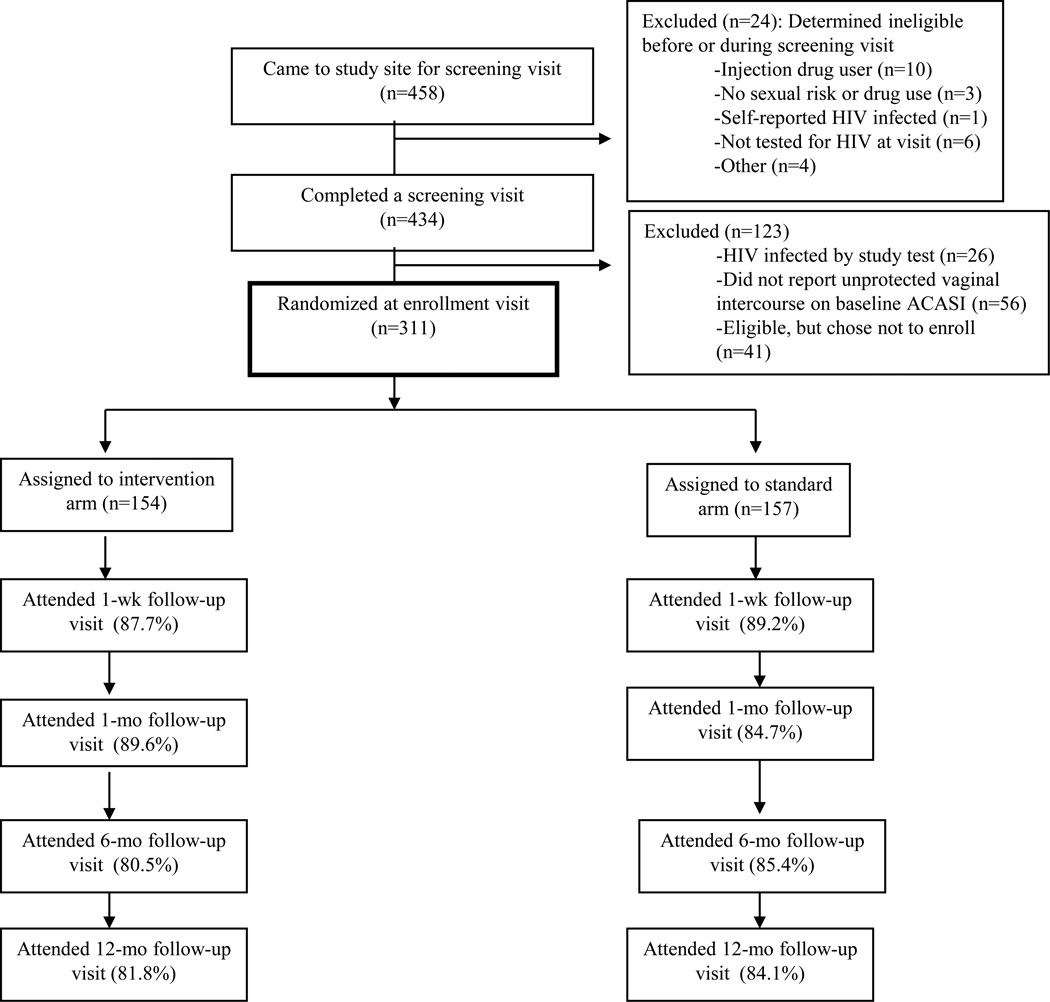

From March 2005 through June 2006, 458 women came to the research site, of whom 434 (94.8%) completed a screening visit (Figure 1). Of those, 311 (71.7%) returned for an enrollment visit and were randomized. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between those randomized and not randomized. The mean age of the randomized participants was 42.3 years; most of the women were either African American (65.8%) or Latina (24.1%), and most (67.0%) had less than a high school education. Over half (54.3%) of the women were frequent users of crack cocaine in the prior three months, 26.8% were heavy alcohol users and 27.8% used cocaine frequently. With regard to sexual risk behaviors in the three months before the visit, 35.6% of women reported having ten or more male partners and 85.7% reported having at least one male partner from whom they received money or drugs for sex (exchange partner). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics by arm of the study (Table 1). During follow-up, two HIV infections occurred with an estimated HIV incidence rate of 0.7 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 0.2, 2.7).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of trial, UNITY Study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by arm of study, UNITY Study, 2005-2007

| Characteristic | Interventing | Standard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p-value | |

| Age | |||||

| 18–40 | 61 | 40.1 | 46 | 29.7 | 0.137 |

| 41–45 | 40 | 26.3 | 52 | 33.6 | |

| 46+ | 51 | 33.6 | 57 | 36.8 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 98 | 64.5 | 104 | 67.1 | 0.604 |

| Latina | 36 | 23.7 | 38 | 24.5 | |

| Mix/white/other | 18 | 11.8 | 13 | 8.4 | |

| Place of birth | |||||

| In NYC area | 123 | 80.9 | 123 | 79.4 | 0.921 |

| Somewhere else in US | 18 | 11.8 | 19 | 12.3 | |

| Other | 11 | 7.2 | 13 | 8.4 | |

| Unemployed | 145 | 96.0 | 143 | 93.5 | 0.317 |

| Annual income <$12,000 | 132 | 90.4 | 131 | 90.3 | >0.999 |

| Educational level (years) | |||||

| Less than 9 years | 14 | 9.3 | 17 | 11.1 | 0.709 |

| 9–11 years | 87 | 58.0 | 85 | 55.6 | |

| High school graduate | 34 | 22.7 | 40 | 26.1 | |

| Some college + | 15 | 10.0 | 11 | 7.2 | |

| Had health insurance | 133 | 87.5 | 130 | 84.4 | 0.511 |

| Current living situation | |||||

| Living with someone | 71 | 50.7 | 78 | 54.6 | 0.576 |

| Homeless | 41 | 29.3 | 34 | 23.8 | |

| Living in multiple places | 28 | 20.0 | 31 | 21.7 | |

| Ever in jail | 91 | 60.3 | 92 | 59.4 | 0.871 |

| Locations where stayed overnight at least once in last year* | |||||

| Shelter or welfare residence | 63 | 41.5 | 58 | 37.4 | 0.486 |

| Jail or prison | 32 | 21.1 | 30 | 19.4 | 0.777 |

| Drug treatment | 28 | 18.4 | 28 | 18.1 | >0.999 |

| No fixed address (street, park etc) | 12 | 7.9 | 17 | 11.0 | 0.436 |

| Group home or halfway house | 2 | 1.3 | 7 | 4.5 | 0.173 |

| In last three months… | |||||

| No. of male partners | |||||

| 0–1 | 18 | 11.8 | 15 | 9.9 | 0.857 |

| 2–5 | 50 | 32.9 | 46 | 30.5 | |

| 6–9 | 33 | 21.7 | 33 | 21.9 | |

| 10+ | 51 | 33.6 | 57 | 37.8 | |

| Had a steady partner | 112 | 73.7 | 108 | 69.7 | 0.450 |

| Among those with a steady partner, unprotected vaginal sex with steady | 81 | 89.0 | 80 | 92.0 | 0.613 |

| Had 1+ casual partners | 119 | 78.3 | 123 | 79.4 | 0.819 |

| Among those with casual partners, unprotected vaginal sex with casuals | 79 | 71.2 | 86 | 76.8 | 0.363 |

| Had 1+ exchange partners | 128 | 84.2 | 135 | 87.1 | 0.517 |

| Among those with exchange partners, unprotected vaginal sex with exchange | 77 | 65.8 | 81 | 64.8 | 0.893 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex | 141 | 95.9 | 141 | 97.9 | 0.501 |

| Unprotected anal sex | 49 | 34.8 | 51 | 36.4 | 0.804 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| None | 31 | 20.8 | 35 | 22.9 | 0.726 |

| Light | 41 | 27.5 | 35 | 22.9 | |

| Moderate | 36 | 24.2 | 43 | 28.1 | |

| Heavy | 41 | 27.5 | 40 | 26.1 | |

| Crack use | |||||

| Never | 25 | 16.8 | 16 | 10.6 | 0.219 |

| Occasional | 49 | 32.9 | 47 | 31.1 | |

| Frequent | 75 | 50.3 | 88 | 58.3 | |

| Cocaine use | |||||

| Never | 58 | 38.9 | 44 | 28.8 | 0.153 |

| Occasional | 51 | 34.2 | 65 | 42.5 | |

| Frequent | 40 | 26.9 | 44 | 28.8 | |

| Heroin use | |||||

| Never | 101 | 66.9 | 89 | 57.8 | 0.261 |

| Occasional | 28 | 18.5 | 36 | 23.4 | |

| Frequent | 22 | 14.6 | 29 | 18.8 | |

| Knowledge of HIV vaccines (mean/median score) (SD) | 5.6/ 6.0 | 3.4 | 5.3/ 5.00 | 3.7 | 0.501 |

Multiple answers allowed

Adherence to intervention and standard conditions and retention

For measuring counselor adherence to the enhanced and standard HIV vaccine education sessions, 73 tapes were reviewed (42 for the enhanced; 31 for the standard). The mean percent of the total possible score was 98.8% for the enhanced vaccine education sessions and 89.3% for the standard vaccine education sessions. A total of 171 tapes were reviewed for counselor adherence to the enhanced and standard risk reduction counseling sessions. For the enhanced risk reduction counseling sessions (84 tapes), the mean percent of the total possible score was 82.5%, and for the standard risk reduction counseling sessions (87 tapes), the mean percent was 88.4%.

Completion of the intervention and standard condition sessions was high. For vaccine education, 87.7% of intervention group women and 89.2% of standard arm group women completed both vaccine education sessions. For risk reduction counseling, 75.3% of intervention group women and 76.4% of standard arm group women completed all three risk reduction sessions, with 94.8% and 93.6% of intervention and standard arm group women completing at least 2 of the 3 risk reduction sessions, respectively. Visit retention rates were above 80% in the enhanced arm and above 84% in the standard arm over the course of the follow-up period (Figure 1). There were no statistical differences in retention at each visit by arm of the study.

Outcomes

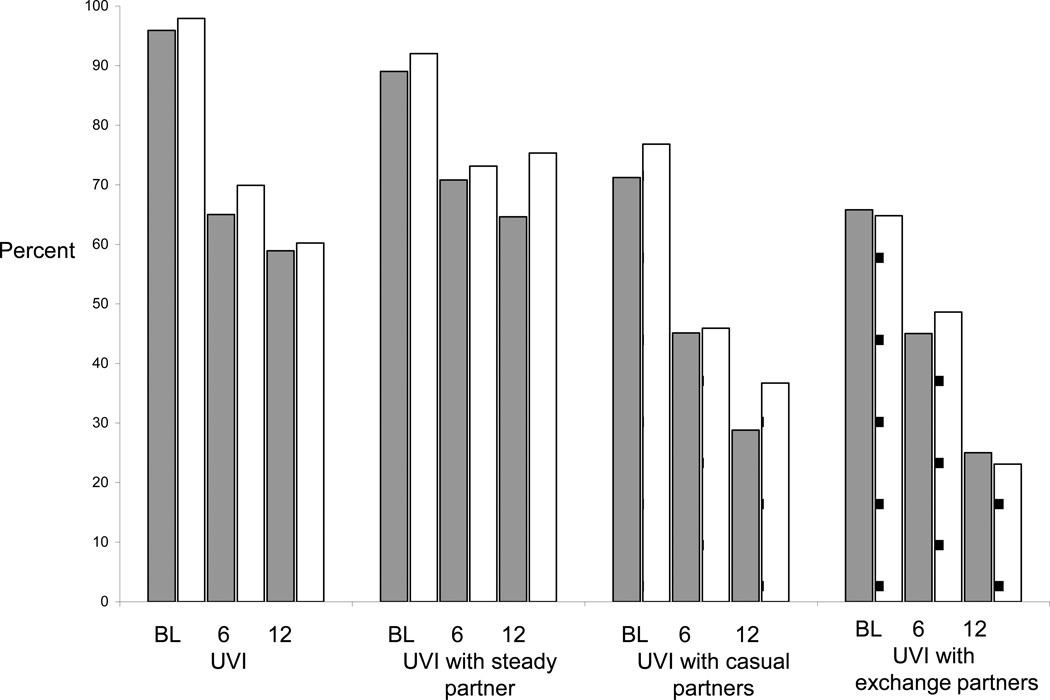

The percent of women reporting unprotected vaginal sex declined significantly from baseline to Month 12 (Figure 2) (all p-values <0.0001 comparing baseline to Month 6 and baseline to Month 12). However, no significant differences were found by study arm for any follow-up study visit. Similar findings were observed for unprotected vaginal sex with steady, casual and exchange partners. Similarly, the mean log VEE at Month 6 and Month 12 did not significantly differ by study arm (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Percent of women reporting sexual risk behaviors by study arm and visit

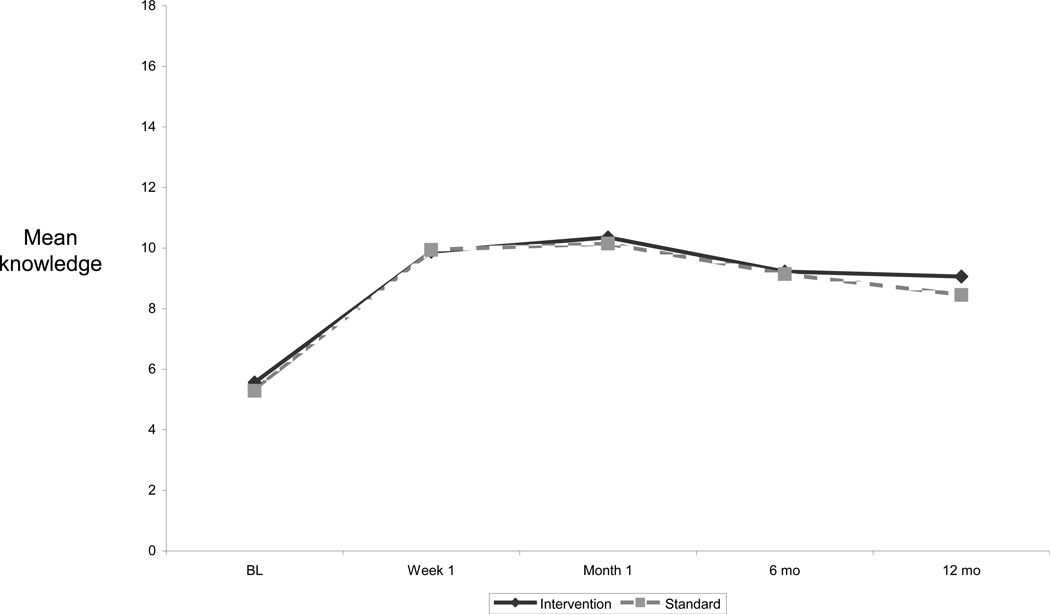

At baseline, HIV vaccine knowledge was low with a mean number of 5.4 (S.D. = 3.6) of 18 items correct. The mean number of correct items significantly increased to 9.9 (S.D. = 3.7) at Week 1 (p <0.0001), and to 10.3 (S.D. = 3.6) at Month 1 (p=0.0027 compared to Week 1) and then declined to 9.2 (S.D. = 3.8) at Month 6 (p < 0.0001 compared to Month 1) and to 8.8 (S.D. = 3.8) at Month 12 (p=0.1654 compared to Month 6) (Figure 3). The mean score was not significantly different between study arms at each study visit (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean number of HIV vaccine knowledge items correct by study arm and visit

Table 2 presents the percent of all women (both study arms) responding correctly to each knowledge item at baseline and Month 1, after receiving both vaccine education sessions. For 15 of the 18 items, there was a significant increase in the percent of women who were correct between baseline and Month 1. The three items for which there was no increase were in reference to testing a vaccine for both efficacy and safety, assurances of safety, and guarantees about participation in future vaccine trials. There were an additional two items which less than 50% of women did not identify correctly at Month 1 (medical care and assumption about any protective effect of a vaccine being tested). For half of the items, the percent correct significantly declined between Month 1 and Month 12.

Table 2.

Percent of women correct on specific HIV vaccine concepts both study arms combined: Baseline to 12 month visit, UNITY Study, 2005–2007

| Knowledge item | Baseline % |

Month 1 % |

Month 12 % |

Baseline to Month 1 p-value |

Month 1 to Month 12 p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People in the vaccine study can get free HIV testing through the study as often as they want (True) | 51.8 | 85.0 | 74.4 | <0.0001 | 0.0014 |

| A test HIV vaccine could not give people HIV (True) | 48.7 | 74.9 | 67.7 | <0.0001 | 0.0568 |

| People may mistakenly think that participants in HIV vaccine studies are HIV-infected (True) | 45.5 | 73.7 | 61.4 | <0.0001 | 0.0013 |

| People who get the vaccine in a vaccine study will be protected against HIV for at least three years (False) | 35.2 | 57.7 | 46.1 | <0.0001 | 0.0022 |

| In a vaccine study, some participants will get the real vaccine, and some will get a placebo (an inactive substance) (True) | 34.5 | 87.6 | 81.5 | <0.0001 | 0.0704 |

| People in a vaccine study can stop coming to the clinic as soon as they have gotten all their injections (False) | 34.2 | 65.2 | 52.6 | <0.0001 | 0.0046 |

| If people test HIV antibody-positive after getting a test HIV vaccine, they may really be infected with HIV, or they may just be responding to the vaccine (True) | 33.2 | 57.3 | 48.4 | <0.0001 | 0.0772 |

| A vaccine that prevents HIV is already available to use (False) | 30.9 | 70.4 | 51.6 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Vaccine studies will enroll people who already have HIV and people who do not have HIV (False) | 30.9 | 67.0 | 43.3 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| In a vaccine study, the study nurse will decide who gets the real vaccine and who gets the placebo (False) | 29.3 | 62.9 | 50.2 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 |

| A test HIV vaccine may affect a participant’s HIV antibody test results (True) | 27.6 | 55.1 | 51.6 | <0.0001 | 0.4865 |

| People in a vaccine study will know whether or not they got placebo (False) | 24.1 | 64.0 | 59.8 | <0.0001 | 0.0568 |

| In a vaccine study, the researchers are testing the vaccine only to see if it works (False) | 21.4 | 11.2 | 18.9 | 0.0008 | 0.0001 |

| People in a vaccine study will know whether or not they got the placebo because only the vaccine will cause side effects (False) | 20.4 | 73.8 | 66.1 | <0.0001 | 0.5472 |

| People in a vaccine study are guaranteed a chance to be in any future vaccine studies (False) | 19.7 | 23.2 | 24.0 | 0.7389 | 0.7815 |

| Once a large-scale HIV vaccine study begins, we can be sure the vaccine is completely safe (False) | 19.4 | 27.4 | 23.2 | 0.0620 | 0.5151 |

| People in a vaccine study will receive health care for any medical problems they have, whether or not the problems are related to the study (False) | 18.2 | 29.6 | 27.6 | 0.0023 | 0.7893 |

| Only vaccines that are known to be at least 50% effective at preventing HIV will be tested in vaccine studies (False) | 18.1 | 39.7 | 26.9 | <0.0001 | 0.0105 |

DISCUSSION

The results of the UNITY Study are disappointing in terms of the designed interventions and clearly point to areas for future research. In reference to knowledge of HIV vaccine trial concepts, overall, it was reassuring that women increased their knowledge of almost all HIV vaccine concepts after receiving two sessions of vaccine education. However, even with the increase in knowledge overall, there were a number of concepts that were not adequately addressed in either the standard or enhanced conditions, as illustrated by at least 50% of the women incorrectly answering concepts related to testing a vaccine for both efficacy and safety, guarantees about participation in future vaccine trials, assurances of safety, medical care, and assumptions about any protective effect of a vaccine being tested. Furthermore, there was no apparent advantage of using pictures, diagrams and application vignettes for increasing knowledge over the standard condition. This lack of difference between study conditions may have been due to the success of the standard condition in increasing vaccine knowledge, as illustrated by the initial randomized studies by Coletti et al17 and Murphy et al20. In the study by Coletti et al17, the mean number correct of ten items increased from 4.7 at baseline to 7.0 at the 6-month visit in the group that received similar vaccine education as was in the standard arm of the UNITY Study.

Other studies have examined the consent process for HIV-related studies and aids to improve the process using educational videos, posters, flipcharts, multiple sessions and non-medical personnel to enhance understanding19;29;30. Most of these studies were not randomized trials or did not have a comparison group. Systematic reviews of informed consent interventions have not found approaches which clearly are significantly better31;32. Furthermore, there is a limited literature concerning the informed consent process related to HIV, and even fewer related to HIV vaccine efficacy trials.

In actual HIV vaccine efficacy trials, vaccine trial education is incorporated in the informed consent process and a sufficient level of understanding must be demonstrated by participants before enrollment can occur33. The results of this study suggest that some high-risk individuals may be excluded from trials due to a lack of understanding of certain vaccine trial concepts. Thus, these results suggest that more research is needed in this area to assure adequate representation of subgroups of at-risk populations, while meeting the ethical obligation of soliciting truly informed consent.

In the UNITY Study, a decline in sexual risk behaviors was observed in both arms, in particular with casual and exchange partners. These results suggest that a Project Respect-based intervention is as effective as the alternative approach tested here which included interactive modules that approached sexual risk reduction from a variety of strategies and that a Project Respect-based risk reduction counseling model may be appropriate for vaccine trials. The lack of difference between study conditions may, again, be due to the effectiveness of the control condition. Furthermore, the women recruited had significant life stressors, such as substance use and homelessness that, while addressed individually in the counseling, may have made the effects of an intervention more difficult to realize given that HIV prevention may not have been the most important issue for immediate attention34. Even with the significant declines in reported risk behaviors, attention needs to be directed towards strengthening interventions within the context of vaccine trials to help women reduce their risk with their steady partners, in particular if those partners are characterized by risk factors such as high levels of concurrency and incarceration, important factors in the heterosexual spread of HIV in the United States35;36.

There are limitations to the study which should be acknowledged. The results could have been affected by loss to follow up. However, retention was not significantly related to treatment assignment. Self-reported sexual risk behavior data may not have been an accurate reflection of the actual risk behavior practiced by the participant. However, ACASI was used as the data collection method for all study outcomes, which tends to reduce socially desirable responding. Furthermore, the finding that the least amount of risk reduction occurred with steady partners is consistent with other studies37. Blinding of the counselor and study participants was not possible and could have led to observer bias. However, we carefully trained counselors in this respect and delivery of the intervention was divorced from data collection in order to minimize the potential for socially-desirable responding selectively among participants in the intervention arm. Since counselors were trained to deliver both conditions, there is the possibility of cross-contamination. However, reviews of session tapes indicated high adherence to the intervention and control manuals. The sample was not of sufficient size to use a biologic outcome, such as incident HIV infection, as a measure of intervention effect. The measurement of HIV vaccine trial concept knowledge was based on a true/false ‘test’ and thus, may have overestimated knowledge levels38. Finally, the sample may not be fully representative of non-injection drug using women since we recruited them using a variety of outreach strategies and with specific eligibility criteria. However, similar eligibility may be used to enroll women enrolling in vaccine trials, and thus our sample may be more generalizable to such a group.

In summary, the results of the UNITY Study suggest that further research is needed to boost vaccine educational efforts to assure inclusion of subgroups of high-risk individuals and to strengthen risk reduction interventions in targeted areas of need.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nikki Englert, Sean Lawrence, and Evelyn Rivera for their work and devotion in conducting this study, the Project ACHIEVE Community Advisory Board for their advice and contributions, and the study participants who gave their time and effort.

This work was supported by a grant to the New York Blood Center from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH (R01 DA017482).

Clinical Trials Number: NCT00150098

Footnotes

All authors contributed to the study conception, design and implementation.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer R, Kaplan EH, McKenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system--United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gollub EL. A neglected population: drug-using women and women’s methods of HIV/STI prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20:107–120. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross MW, Hwang LY, Zack C, Bull L, Williams ML. Sexual risk behaviours and STIs in drug abuse treatment populations whose drug of choice is crack cocaine. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:769–774. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW. Who’s getting the message? Intervention response rates among women who inject drugs and/or smoke crack cocaine. Prev Med. 2003;37:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston MI, Fauci AS. An HIV vaccine--challenges and prospects. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:888–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartholow BN, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Goli V, Koblin B, Para M, Marmor M, Novak RM, Mayer K, Creticos C, Orozco-Cronin P, Popovic V, Mastro TD. HIV sexual risk behavior over 36 months of follow-up in the world’s first HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:90–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143600.41363.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. Ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine research. Geneva: 2000. Ref Type: Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Methodologic challenges in biomedical HIV prevention trials. 2008. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22:1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, Flores SA, Peersman G, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Review and meta-analysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(Suppl 1):S106–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of human subjects. Code of Federal Regulations. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariner WK. Taking informed consent seriously in global HIV vaccine research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:117–123. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindegger G, Richter LM. HIV vaccine trials: critical issues in informed consent. S Afr J Sci. 2000;96:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koblin BA, Heagerty P, Sheon A, Buchbinder S, Celum C, Douglas JM, Gross M, Marmor M, Mayer K, Metzger D, Seage G. Readiness of high-risk populations in the HIV Network for Prevention Trials to participate in HIV vaccine efficacy trials in the United States. AIDS. 1998;12:785–793. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koblin BA, Holte S, Lenderking B, Heagerty P. Readiness for HIV vaccine trials: changes in willingness and knowledge among high-risk populations in the HIV network for prevention trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:451–457. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coletti AS, Heagerty P, Sheon AR, Gross M, Koblin BA, Metzger DS, Seage GR., III Randomized, controlled evaluation of a prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:161–169. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200302010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy DA, Hoffman D, Seage GR, III, Belzer M, Xu J, Durako SJ, Geiger M. Improving comprehension for HIV vaccine trial information among adolescents at risk of HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19:42–51. doi: 10.1080/09540120600680882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joseph P, Schackman BR, Horwitz R, Nerette S, Verdier RI, Dorsainvil D, Theodore H, Ascensio M, Henrys K, Wright PF, Johnson W, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. The use of an educational video during informed consent in an HIV clinical trial in Haiti. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:588–591. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229998.59869.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy DA, O’Keefe ZH, Kaufman AH. Improving comprehension and recall of information for an HIV vaccine trial among women at risk for HIV: reading level simplification and inclusion of pictures to illustrate key concepts. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindegger G, Slack C, Vardas E. HIV vaccine trials in South Africa--some ethical considerations. S Afr Med J. 2000;90:769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koblin BA, Xu G, Lucy D, Robertson V, Bonner S, Hoover DR, Fortin P, Latka M. Hepatitis B infection and vaccination among high-risk noninjection drug-using women: baseline data from the UNITY study. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:917–922. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3180ca8f12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latka M, Bonner S, Koblin B, Brown-Peterside P, Lucy D, Fortin P. A report from the UNITY Trial. Philadelphia, PA: American Public Health Association Meeting; 2005. How well do high-risk women who are candidates for HIV vaccine efficacy trials understand HIV vaccine trial procedures and risk? Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Malotte CK, Iatesta M, Kent C, Lentz A, Graziano S, Byers RH, Peterman TA. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Update on adult immunization. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Susser E, Desvarieux M, Wittkowski KM. Reporting sexual risk behavior for HIV: a practical risk index and a method for improving risk indices. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:671–674. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Celum C, Chesney M, Huang Y, Mayer K, Bozeman S, Judson FN, Bryant KJ, Coates TJ. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald DW, Marotte C, Verdier RI, Johnson WD, Jr., Pape JW. Comprehension during informed consent in a less-developed country. Lancet. 2002;360:1301–132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sastry J, Pisal H, Sutar S, Kapadia-Kundu N, Joshi A, Suryavanshi N, Bharucha KE, Shrotri A, Phadke MA, Bollinger RC, Shankar AV. Optimizing the HIV/AIDS informed consent process in India. BMC Med. 2004;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004;292:1593–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agre P, Campbell FA, Goldman BD, Boccia ML, Kass N, McCullough LB, Merz JF, Miller SM, Mintz J, Rapkin B, Sugarman J, Sorenson J, Wirshing D. Improving informed consent: the medium is not the message. IRB. 2003;(Suppl 25):S11–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.HIV Vaccine Trials Network. HVTN Manual of Operations, II. HVTN Policies and Procedures, Informed Consent. 2008 www.hvtn.org. 1-9-0009. Ref Type: Electronic Citation.

- 34.Kalichman SC, Adair V, Somlai AM, Weir SS. The perceived social context of AIDS: study of inner-city sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7:298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Bonas DM, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR. Concurrent sexual partnerships among women in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban M. Sexual Partner Concurrency among STI Clinic Patients with a Steady Partner: Correlates and Associations with Condom Use. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindegger G, Milford C, Slack C, Quayle M, Xaba X, Vardas E. Beyond the checklist: assessing understanding for HIV vaccine trial participation in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:560–566. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000247225.37752.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]