Abstract

Objective

Staphylococcus aureus is a significant cause of infection in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Colonization with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a risk factor for subsequent S. aureus infection. However, MRSA-colonized patients may have more co-morbidities than methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA)-colonized, or non-colonized patients and therefore more susceptible to infection on that basis.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

A 24-bed surgical ICU (SICU) and 19-bed medical ICU (MICU) of a 1252-bed, academic hospital.

Patients

Patients had nasal swab cultures for S. aureus performed upon ICU admission from December 2002 to August 2007

Methods

Patients in the ICU for > 48 hours were examined for an ICU-acquired S. aureus infection, defined as development of S. aureus infection > 48 hours after ICU admission.

Results

One thousand four hundred thirty-three (27.8%) of 5,161 patients had S. aureus colonization at admission [674 (47.0%) with MRSA; 759 (53.0%) with MSSA]. An ICU-acquired S. aureus infection developed in 113 (2.2%) patients. 75 (66.4%) of 113 had an infection due to MRSA. Risk factors associated with an ICU-acquired S. aureus infection included MRSA colonization at admission [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR), 4.70; 95% confidence interval (CI), 3.07–7.21] and MSSA colonization at admission (aHR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.52–4.01).

Conclusion

ICU patients colonized with S. aureus were at greater risk of developing a S. aureus infection in the ICU. Even after adjusting for patient-specific risk factors, MRSA-colonized patients were more likely to develop S. aureus infection compared to MSSA-colonized or non-colonized patients.

Staphylococcus aureus infection is a common cause of healthcare associated infection worldwide. The proportion of S. aureus infection due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains has been increasing over the past decades. MRSA accounts for more than 60% of S. aureus intensive care unit (ICU)-related infections in the U.S.1, 2 The prevalence of MRSA infections in U.S. hospitals is approximately 34 cases per 1,000 admissions.3 MRSA carriage is an important predisposing factor for developing MRSA infection. Approximately 15 to 25 % of MRSA-colonized inpatients developed a subsequent MRSA infection during their hospitalization or within 18 months.4, 5

Previous studies reported that MRSA infections were associated with higher morbidity and mortality compared to infections caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).6, 7 Reduced vancomycin susceptibility and emergence of the community associated genotype have complicated the management of MRSA infections.8, 9

Given the significant impact of MRSA infection, earlier identification of high risk patients (i.e., MRSA-colonized patients) is considered essential for reducing the frequency of overall S. aureus infection. However, MRSA colonization might be a marker of individuals with substantial co-morbidities compared to individuals with MSSA colonization or without S. aureus colonization. Therefore, MRSA-colonized patients may be more susceptible to S. aureus infection on the basis of patient risk factors alone.10 Moreover, previous risk factor studies to examine the role of MRSA colonization and subsequent infection were limited by the sample size or limited patient population.11

The purpose of this study was to determine if MRSA-colonized patients, admitted to medical and surgical ICUs were more likely to develop any S. aureus infection in the ICU, compared to patients colonized with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus or not colonized with S. aureus, independent of predisposing patient risk factors.

METHODS

A prospective cohort study was performed in the 19-bed medical ICU and the 24-bed surgical ICU of Barnes- Jewish Hospital (BJH), a 1,252-bed, academic, tertiary care center in St. Louis, Missouri. The study was conducted between December 2002 and August 2007. This study included a 57-month observation period (2002–2007) in the surgical ICU and a 32-month observation in the medical ICU (2005–2007). An active surveillance program to detect MRSA colonization was implemented in the surgical ICU in December 2002, and then expanded to the medical ICU in January 2005. Nasal cultures for S. aureus were performed for all patients admitted to the ICUs. MRSA surveillance cultures were done as part of routine infection control policy in the hospital. Contact precautions were implemented for ICU patients with MRSA detected by nasal culture or other clinical cultures. Colonized ICU patients did not undergo MRSA decolonization therapy (e.g., mupirocin nasal ointment) and patients at Barnes-Jewish Hospital did not undergo pre-operative MRSA decolonization therapy during the study period.

Demographic and clinical data, including co-morbid conditions and outcomes were obtained for the study population. Skin ulcer was defined as the development of a stage two or greater decubitus ulcer during ICU stay. Nasogastric or Dobhoff tube was defined as a nasoenteric tube. A percutaneous feeding tube was defined as either a gastrostomy, jejunostomy, or gastrojejunostomy tube. All clinical cultures positive for S. aureus were evaluated to determine whether or not these positive cultures were associated with ICU-acquired S. aureus infection.

National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) definitions were used to define ICU-acquired S. aureus infections.12 ICU-acquired S. aureus infection was defined as the development of S. aureus infection (either MRSA or MSSA) > 48 hours after ICU admission and < 48 hours after ICU discharge. The incidence of S. aureus infection was reported per 1,000 ICU-days.1

Exclusion criteria included patients who were < 18 years old, stayed in the ICU < 48 hours, had a known S. aureus infection at ICU admission, or developed S. aureus infection during the first 48 hours of their ICU stay.

S. aureus surveillance swab specimens were collected from both anterior nares of each patient, transported and stored at room temperature and inoculated directly onto Mannitol salt agar plates (Becton Dickinson). The Mannitol salt agar plates were incubated at 35 °C and examined for growth after 24–48 hours. Strains that produced yellow colonies on the screening Mannitol salt agar plates were confirmed as S. aureus by Gram staining, 3% catalase testing, and coagulase testing with the Staph Latex agglutination assay (LifeSign). Confirmed S. aureus isolates were subcultured in Trypase soy broth with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson) and then on oxacillin screening agar containing 6.0 mg/mL of oxacillin (Becton Dickinson) for determining methicillin resistance. Plates were incubated at 35 °C for 18–24 hours and examined for the evidence of growth. Strains showing distinct growth were considered to be methicillin-resistant.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Risk factors for time to first infection after ICU admission were assessed using Cox proportional hazards models. Non-infected patients were also censored on 48 hours after discharge from the ICU. Potential risk factors were first assessed in bivariate analysis. The multivariable model was developed in forward, stepwise fashion. Candidate variables were those with P < .10 in bivariate analysis. Variables were retained in the model if P < .05 or if the variable was a confounder. Two-way interactions were assessed after selection of the main effects. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed via −ln(−ln) survival curves, time-dependent covariates, and Shoenfeld residuals13, 14

The dates of initiation and discontinuation were known for central venous catheterization and mechanical ventilation; thus, these variables were first assessed as time-dependent variables using the counting process approach.15 Because use of these devices have previously been documented to be associated with MRSA infection,16–18 a multivariable model was also constructed and stratified by presence of central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, and per tube nutrition. The Washington University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

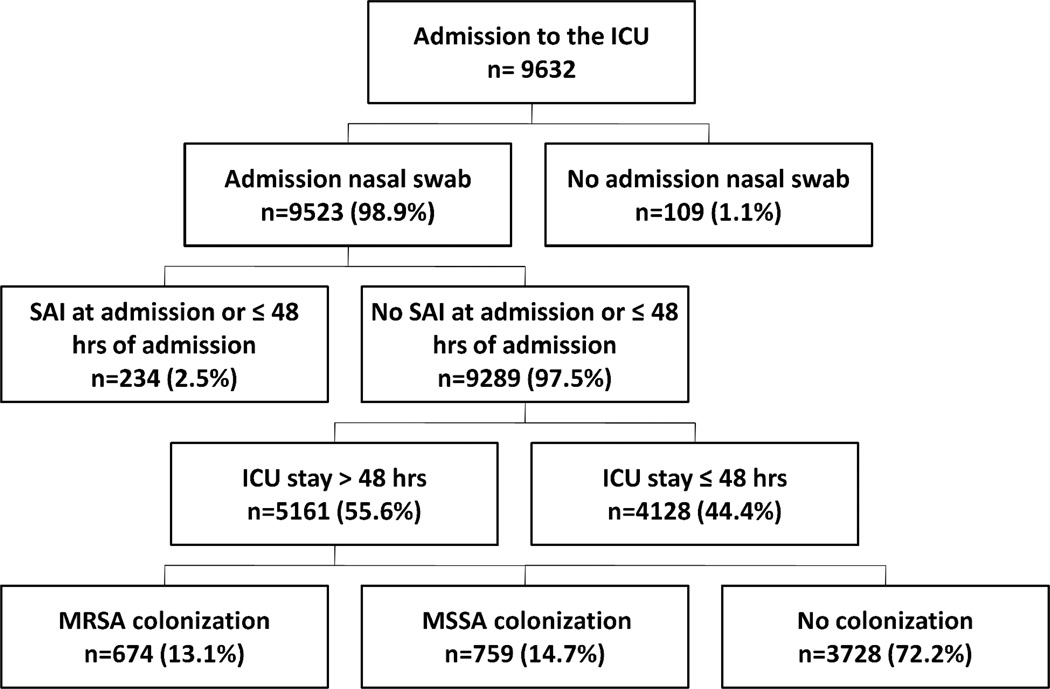

A total of 9,632 patients ≥ 18 years old were admitted to the ICUs during the study period. (6,419 in the surgical ICU and 3,213 in the medical ICU) (Figure 1). Nine thousand five hundred and twenty-three (98.9 %) patients had an admission S. aureus nasal swab culture. Among the 9,523 patients, 234 had a S. aureus infection at ICU admission or within 48 hours of admission. Patients with S. aureus infection at admission or within 48 hours of ICU admission and patients who stayed in the ICU ≤ 48 hours (n = 4,128) were excluded. Of the remaining 5,161 patients, 1,433 (27.8%) had a positive nasal culture for S. aureus [674 (47.0%) patients were MRSA-colonized and 759 (53.0%) were MSSA-colonized].

Figure 1.

Description of the study population

NOTE. Data are no. (%) of patients. ICU, intensive care unit; SAI, Staphylococcus aureus infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA; methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus.

Comparison of patient characteristics based on nasal colonization at ICU admission is shown in Table 1. MRSA-colonized patients were older than either MSSA-colonized or non-colonized patients (median age = 63, 55, and 61 years, respectively). Compared with either MSSA-colonized or non-colonized patients, MRSA-colonized patients were more likely to have multiple co-morbidities including congestive heart failure, malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus, systemic corticosteroid use, skin ulcer, and chronic renal insufficiency. MRSA colonized patients were also more likely to have a recent history of multiple drug-resistant organisms and recent exposure to healthcare facilities. Surgical ICU admission was less common in MRSA-colonized patients compared to MSSA-colonized or non-colonized patients.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients with Colonization Status on Admission to the Intensive Care Units

| Variable | MRSA colonization (n = 674) |

MSSA colonization (n = 759) |

No colonization (n = 3728) |

Colonization MRSA vs. MSSA P |

Colonization MRSA vs. None P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age, median, years (range) | 63 (18–95) | 55 (18–94) | 61 (18–97) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Female | 304 (45.1) | 351 (46.2) | 1661 (44.6) | .665 | .792 |

| White race | 444 (65.9) | 535 (70.5) | 2582 (69.3) | .061 | .081 |

| Surgical ICU admission | 365 (54.2) | 491 (64.7) | 2422 (65.0) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Any BJH admission in the past 12 months | 385 (57.1) | 213 (28.1) | 1343 (36.0) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Location prior to hospital admission | |||||

| Home | 407 (60.4) | 611 (80.5) | 2650 (71.1) | Ref.a | Ref.a |

| Long term care facility | 128 (19.0) | 24 (3.2) | 237 (6.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Outside hospital | 139 (20.6) | 124 (16.3) | 841 (22.6) | <.001 | .488 |

| Condition present at the time of admission | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 154 (22.8) | 76 (10.0) | 488 (13.1) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 197 (29.1) | 104 (13.7) | 692 (18.6) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Malignancy (current diagnosis) | 87 (12.9) | 97 (12.8) | 608 (16.3) | .942 | .026 |

| HIV | 8 (1.2) | 4 (0.5) | 34 (0.9) | .171 | .499 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 264 (39.2) | 207 (27.3) | 1051 (28.2) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Systemic corticosteroid use in past 28 days | 150 (22.3) | 82 (10.8) | 649 (17.4) | <.001 | .003 |

| Skin ulcer | 146 (21.7) | 125 (16.5) | 678 (18.2) | .012 | .033 |

| Baseline renal function | |||||

| Normal renal function | 521 (77.3) | 684 (90.1) | 3098 (83.1) | Ref.a | Ref.a |

| CRF | 103 (15.3) | 56 (7.4) | 403 (10.8) | <.001 | .098 |

| CRF with hemodialysis | 50 (7.4) | 19 (2.5) | 227 (6.1) | .258 | .437 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 48 (7.1) | 62 (8.2) | 261 (7.0) | .457 | .910 |

| History of intravenous drug use | 13 (1.9) | 19 (2.5) | 44 (1.2) | .463 | .114 |

| Solid organ or bone marrow transplant | 21 (3.1) | 15 (2.0) | 149 (4.0) | .169 | .275 |

| Surgical procedure | |||||

| < 90 days prior to ICU admission | 129 (19.1) | 49 (6.5) | 548 (14.7) | <.001 | .003 |

| During current admission | 342 (50.7) | 432 (56.9) | 2212 (59.3) | .019 | <.001 |

| Presence of resistant organism | |||||

| MRSA isolated in the past 6 months | 137 (20.3) | 4 (0.5) | 76 (2.0) | <.001 | <.001 |

| C.difficile infection in the past 3 months | 43 (6.4) | 9 (1.2) | 90 (2.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| VRE isolated in the past 3 months | 74 (11.0) | 15 (2.0) | 168 (4.5) | <.001 | <.001 |

NOTE.

Data are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise specified. ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; BJH, Barnes-Jewish Hospital; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CRF, chronic renal failure; C. difficile, Clostridium difficile; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; Ref, reference category.

Obtained from univariate logistic regression analysis.

One hundred and thirteen (2.2%) patients developed a total of 128 ICU-acquired S. aureus infections during their ICU stay; 11(9.7%) of 113 patients developed multiple ICU-acquired S. aureus infections. MRSA accounted for 66.4% of ICU-acquired S. aureus infections. Median time to development of S. aureus infection from ICU admission was 7 days. Among 128 ICU-acquired S. aureus infections, the most common infection was ventilator-associated pneumonia (39;30.5%). The remaining ICU-acquired S. aureus infections were central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection (19;14.8%), primary bloodstream infection without central venous catheter (16;12.5%), surgical site infection (11;8.6%), hospital acquired pneumonia (without ventilator) (11;8.6%), skin and soft tissue infection (excluding surgical site infection) (9;7.0%), secondary bloodstream infection 7;5.5%), intra-abdominal infection (7;5.5%), musculoskeletal infection (3;2.3%), and other (6;4.7%).

The overall incidence of ICU-acquired S. aureus infection was 2.19 per 1,000 ICU-days. All ICU-acquired S. aureus infections among MRSA-colonized patients were caused by MRSA. The proportion of infections due to MRSA among MSSA-colonized patients and non-colonized patients were 30.8% and 60.0%, respectively (Table2).

Table 2.

Incidence of ICU-acquired S. aureus Infection, by the Nasal Colonization Status on Admission (per 1,000 ICU-days)

| Variable (incidence density) | Colonization status at ICU admission | Risk ratio (95%CI) Colonization MRSA vs. MSSA |

P | Risk ratio (95%CI) Colonization MRSA vs. None |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA (n=674) |

MSSA (n=759) |

None (n=3728) |

|||||

| Any ICU-acquired SAI | 7.00 | 4.40 | 1.71 | 1.59 (1.00–2.53) | .050 | 4.10 (2.47–6.78) | <.001 |

| ICU-acquired MSSA infection | 0 | 3.05 | 0.68 | NA* | _____ | NA* | ____ |

| ICU-acquired MRSA infection | 7.00 | 1.35 | 1.03 | 5.18 (2.74–9.77) | <.001 | 6.83(4.00–11.64) | <.001 |

NOTE.

ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin- susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, CI; Confidence interval, SAI; Staphylococcus aureus infection.

The risk ratio and P value were not calculated for MSSA infection because none of the patients colonized with MRSA on admission developed an ICU-acquired MSSA infection.

Risk factors independently associated with ICU-acquired S. aureus infections were MRSA colonization on admission [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR), 4.70; 95% confidence interval (CI), 3.07–7.21], MSSA colonization on admission (aHR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.52–4.01), skin ulcer (aHR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.11–2.54), surgical procedure during the hospitalization (aHR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.02–2.50), mechanical ventilation during ICU stay (aHR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.06–2.51) (time dependent variable), and younger age at ICU admission (aHR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98–1.00) (Table 3). Stratified multivariate models based on the presence or absence of a central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, and per tube enteral nutrition were also constructed. Results in stratified models were similar to that in non-stratified model (data not shown)

Table 3.

Risk Factors for S. aureus Infection in the Intensive Care Units

| Characteristics | ICU-acquired S. aureus infection | Crude Hazard Ratio* (95%CI) |

P | Adjusted Hazard Ratio┼ (95%CI) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n= 113) | No (n=5048) | |||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age, median, years (range) | 56 (20–94) | 60 (18–97) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | .075 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | .031 |

| Female | 45 (39.8) | 2271 (45.0) | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | .553 | ||

| White race | 74 (65.5) | 3487 (69.1) | 0.78 (0.53–1.15) | .210 | ||

| Surgical ICU admission | 82 (72.6) | 3196 (63.3) | 1.18 (0.78–1.78) | .442 | ||

| Location prior to hospital admission | ||||||

| Home | 82 (72.6) | 3586 (71.0) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Long term care facility | 5 (4.4) | 384 (7.6) | 0.62 (0.25–1.53) | .299 | ||

| Outside hospital | 26 (23.0) | 1078 (23.1) | 0.95 (0.61–1.47) | .802 | ||

| Any BJH admission in the past 12 months | 28 (24.8) | 1913 (37.9) | 0.63 (0.41–0.96) | .033 | ||

| Condition present at ICU admission | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 10 (8.8) | 708 (14.0) | 0.65 (0.34–1.25) | .198 | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 (13.3) | 977 (19.4) | 0.65 (0.38–1.12) | .119 | ||

| Malignancy (current diagnosis) | 17 (15.0) | 775 (15.4) | 1.14 (0.68–1.91) | .618 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (34.5) | 1483 (29.4) | 1.24 (0.84–1.83) | .273 | ||

| Systemic corticosteroid use in past 28 days | 20 (17.7) | 861 (17.1) | 0.98 (0.60–1.59) | .926 | ||

| Skin ulcer | 58 (51.3) | 891 (17.7) | 1.98 (1.34–2.93) | <.001 | 1.68 (1.11–2.54) | .014 |

| Baseline renal function | ||||||

| Normal renal function | 105 (92.9) | 4198 (83.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| CRF | 7 (6.2) | 555 (11.0) | 0.53 (0.25–1.13) | .101 | ||

| CRF with hemodialysis | 1 (0.9) | 295 (5.8) | 0.16 (0.02–1.12) | .065 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 9 (8.0) | 362 (7.2) | 1.23 (0.62–2.43) | .556 | ||

| History of intravenous drug use | 3 (2.7) | 73 (1.4) | 1.89 (0.60–5.96) | .277 | ||

| Surgical procedure | ||||||

| < 90 days prior to ICU admission | 13 (10.6) | 714 (14.1) | 0.68 (0.38–1.24) | .213 | ||

| During hospitalization | 86 (76.1) | 2900 (57.4) | 1.61 (1.04–2.49) | .033 | 1.60 (1.02–2.50) | .040 |

| ICU related event | ||||||

| Central venous catheter present during | 95 (84.1) | 3509 (69.5) | 0.77 (0.52–1.15) | .201 | ||

| ICU stay* - time dependent | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation during ICU | 103 (91.2) | 3457 (68.5) | 1.96 (1.31–2.92) | .001 | 1.63 (1.06–2.51) | .026 |

| stay* - time dependent | ||||||

| Enteral nutrition during ICU stay* | ||||||

| None | 27 (23.9) | 3295 (65.3) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Via naso-enteric feeding tube | 60 (53.1) | 1311 (26.0) | 1.86 (1.14–3.05) | .014 | ||

| Via percutaneous feeding tube | 11 (9.7) | 299 (5.9) | 1.80(0.87–3.70) | .112 | ||

| Via both | 15 (13.3) | 143 (2.8) | 2.58 (1.30–5.10) | .007 | ||

| Presence of resistant organism | ||||||

| MRSA isolated in the past 6 months | 5 (4.4) | 212 (4.2) | 1.12 (0.46–2.75) | .801 | ||

| C.difficile infection in the past 3 months | 1 (0.9) | 141 (2.8) | 0.28 (0.04–2.07) | .217 | ||

| VRE isolated in the past 3 months | 4 (3.5) | 253 (5.0) | 0.70 (0.26–1.89) | .479 | ||

| Colonization status at ICU admission | ||||||

| No colonization on admission | 50 (44.2) | 3678 (72.9) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| MSSA colonization on admission | 26 (23.0) | 733 (14.5) | 2.58 (1.61–4.15) | <.001 | 2.47 (1.52–4.01) | <.001 |

| MRSA colonization on admission | 37 (32.7) | 637 (12.6) | 4.37 (2.85–6.68) | <.001 | 4.70 (3.07–7.21) | <.001 |

NOTE.

Data are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise specified. ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; BJH, Barnes-Jewish Hospital; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CRF, chronic renal failure; C. difficile, Clostridium difficile; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; Ref, reference category.

Variables considered but not retained in the final model were any BJH admission in the past 12 months, CRF with hemodialysis, enteral nutrition during ICU stay (via naso-enteric tube, percutaneous tube, and via both).

Follow-up days median (range):CVC 6 (2–109), no CVC 3(2–65), P <.001; MV 6 (2–109), no MV 3 (2–26), P <.001; tube EN 11 (2–109), no tube EN 3 (2–48), P <.001]

Stratified multivariate model was also constructed by central venous catheterization, mechanical ventilation and per tube enteral nutrition. Results in stratified model were similar to that in non-stratified model (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies have reported a relationship between nasal colonization status and subsequent S. aureus infection, few studies have compared nasal colonization with MSSA or MRSA and the development of ICU-acquired S. aureus infection. This study showed that nasal colonization with S. aureus was associated with a 2.5 to 4.7-fold increased risk of ICU-acquired S. aureus infection compared with non-colonized patients, even after adjusting for underlying patient risk factors.

It remains unclear why MRSA-colonized patients more frequently develop S. aureus infection compared with MSSA-colonized patients. While patient co-morbidities, presence of devices, and invasive procedures may facilitate the development of MRSA infections, our analysis controlled for these factors. Potential factors for the increased incidence rate of S. aureus infection in MRSA-colonized patients could be the presence of virulent factors and higher bacterial burden at colonized sites.19, 20 These factors might be associated with increasing tissue invasiveness and lead to incidence risk of infection. However, the relationship between virulence factors and subsequent incidence of S. aureus infection is not completely understood.

The incidence of ICU-acquired S. aureus infection in this cohort was 2.3%, which is similar to previous studies of S. aureus infection incidence in ICUs (2% to 6%).21, 22 The prevalence of MRSA colonization in this cohort was 13.1 %, and the overall prevalence of S. aureus colonization at ICU admission was 27.8 %. These findings are slightly higher than previously reported colonization rate in ICU at US hospitals, ranging from 6–9 % for MRSA and 23–24 % for S. aureus.4, 23, 24 Although the difference in nasal colonization rate between this cohort and previous studies from US hospital are not completely clear, the difference in acquisition rate of nasal swab culture at ICU admission potentially influence the overall colonization rate. Acquisition rate of nasal swab in this cohort was 98.9 %, which was significantly higher than that in previous studies (75–76%).4, 23, 24 The large prospective cohort and the high rate of nasal swab culture acquisition over the 4-year study period represent major strengths of this study.

In bivariate risk factor analysis, several risk factors, including hospital admission in the last 12 months, chronic renal failure, and chronic renal failure with hemodialysis surprisingly were protective against ICU-acquired S. aureus infection, although these variables were not statistically significant in multivariate model. After additional analysis, we found that patients with these factors were more likely to have a S. aureus infection at or within 48 hours of ICU admission, and therefore be excluded from our study (data not shown).

Several patient-related factors were independently associated with developing an ICU-acquired S. aureus infection, including surgical procedure during the ICU stay, the development of skin ulcer, and mechanical ventilation during ICU stay. Surgical patients are at increased risk of developing S. aureus infections. Risk factors for S. aureus infections in surgical patients include undergoing emergent surgery, clean-contaminated surgery, or prolonged duration of surgery.25 We found the presence of a skin ulcer was associated with developing a subsequent S. aureus infection as have others.26 Impairment of skin integrity may result in increased burden of S. aureus, leading to subsequent infection. Mechanical ventilation is associated with ventilator associated S. aureus pneumonia. MRSA is one of the most common cause of ventilator associated pneumonia.27 Interestingly, older patients had lower risk for developing S. aureus infection. Previous studies have variable association between age and S. aureus infection in healthcare settings. Some studies reported S. aureus infection increased with older age, or showed no association with age.4, 5 One study reported that S. aureus infection was more commonly seen in younger patients, however the authors concluded that this finding was associated with poor functional status in an age-stratified model.28 A potential explanation for the relationship between age and ICU-acquired S. aureus infection in our cohort could be that younger S. aureus infected patients in our study tended to have severe traumatic injury (e.g., motor vehicle accident and assault). Trauma patients are at higher risk for S. aureus infection.29

Nasal colonization with MRSA at ICU admission was the strongest independent predictor for the development of S. aureus infection. These findings support strategies such as decolonization of MRSA-colonized patients in the ICU to try to reduce subsequent S. aureus infection in the ICU. Currently, few interventions for reducing MRSA colonization prevalence have been assessed in healthcare settings. The use of intranasal mupirocin ointment, oral antimicrobials, and chlorhexidine bathing, either alone or in combination, may prevent subsequent MRSA infection.30–34 However, the ideal strategies to prevent MRSA colonization and infection in healthcare settings remain unclear at this time. Eliminating S. aureus colonization may not be easily achieved by antibiotic-based regimens given the emergence of mupirocin resistance, the high rate of re-colonization, and cost and labor issues to implement comprehensive decolonization strategies.35, 36

This study has some limitations. As with any observational study, even after adjusting for known predisposing factors, other unmeasured factors may still cause ICU-acquired S. aureus infection. Another limitation was the lack of molecular typing of the S. aureus isolates to determine the original sources of infection (i.e., endogenous or exogenous source). However, von Eiff et al. reported a high genotypic correlation between nasal S. aureus isolates and subsequent S. aureus bloodstream isolates, pointing to the patient’s own flora as the primary source of S. aureus infection.37 In our cohort, both MRSA- and MSSA-colonized patients tended to develop infection with the same phenotypic strain of S. aureus suggesting endogenous sources, however that was less likely to occur among MSSA-colonized individuals. Transmission of MRSA could occur despite use of contact precaution for known MRSA carriers.16 It was undetermined whether the source of MRSA infection among non-colonized or MSSA-colonized patients were extra-nasal endogenous source or exogenous source in this cohort. Further studies using molecular typing with a larger sample size may improve our understanding of the relationship between S. aureus transmission and acquisition in the ICU. Due to costs and labor constraints, we only obtained anterior nares surveillance culture, which may underestimate the prevalence of S. aureus-colonized patients. Nasal swab cultures alone can miss 15% of MRSA carriers.38 Detection of extranasal colonized individual might be important especially community-acquired MRSA genotype strains.39

This study demonstrates that S. aureus nasal colonization is independently associated with ICU-acquired S. aureus infection and that MRSA-colonized ICU patients are more likely to become infected even after adjusting for patient co-morbidites and ICU process of care. While many issues regarding the detection, eradication, and prevention of S. aureus infection remain unresolved, it is necessary to assess the benefits of focused and comprehensive decolonization interventions to reduce the overall rate of S. aureus infection in the ICU. Our results suggest developing effective methods of MRSA decolonization and preventing MRSA colonization should be a major component of these strategies.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Mrs. Cherie Hill for the management of study data, and Ms. Sondra Seiler, who assisted in data collection

Financial support: Funded by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Epicenters (1U01CI0000333-01) and M.J.K is funded by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research(UL1 RR024992).

Footnotes

Presented in part : 19th Annual Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

Potential conflict of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calfee DP, Salgado CD, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent transmission of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S62–S80. doi: 10.1086/591061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(8):470–485. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvis WR, Schlosser J, Chinn RY, Tweeten S, Jackson M. National prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in inpatients at US health care facilities, 2006. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(10):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):776–782. doi: 10.1086/422997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang SS, Platt R. Risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection after previous infection or colonization. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):281–285. doi: 10.1086/345955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, Colardyn FA. Outcome and attributable mortality in critically Ill patients with bacteremia involving methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2229–2235. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(1):53–59. doi: 10.1086/345476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soriano A, Marco F, Martinez JA, et al. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(2):193–200. doi: 10.1086/524667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller LG, Diep BA. Clinical practice: colonization, fomites, and virulence: rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):752–760. doi: 10.1086/526773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safdar N, Maki DG. The commonality of risk factors for nosocomial colonization and infection with antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, enterococcus, gram-negative bacilli, Clostridium difficile, and Candida. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(11):834–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safdar N, Bradley EA. The risk of infection after nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Med. 2008;121(4):310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(5):309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival Analysis: A self-learning text. Second Edition. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards model. Biometrika. 1982;69:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen PK, Gill RD. Cox regression model for counting processes: A large sample study. Annals of Statistics. 1982;(10):1100–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren DK, Guth RM, Coopersmith CM, Merz LR, Zack JE, Fraser VJ. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in a surgical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(10):1032–1040. doi: 10.1086/507919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oztoprak N, Cevik MA, Akinci E, et al. Risk factors for ICU-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trouillet JL, Chastre J, Vuagnat A, et al. Ventilator associated pneumonia caused by potentially drug-resistant bacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:531–539. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9705064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, Gray PJ, Murray CK. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(7):971–979. doi: 10.1086/423965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wertheim HF, Vos MC, Ott A, et al. Risk and outcome of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in nasal carriers versus non-carriers. Lancet. 2004 Aug 21–27;364(9435):703–705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.arrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Kallel H, et al. Colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in ICU patients: morbidity, mortality, and glycopeptide use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(11):687–692. doi: 10.1086/501846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbella X, Dominguez MA, Pujol M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage as a marker for subsequent staphylococcal infections in intensive care unit patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16(5):351–357. doi: 10.1007/BF01726362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keene A, Vavagiakis P, Lee MH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and the risk of infection in critically ill patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(7):622–628. doi: 10.1086/502591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Paule SM, et al. Universal surveillance for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 affiliated hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 18;148(6):409–418. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harbarth S, Huttner B, Gervaz P, et al. Risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(9):890–893. doi: 10.1086/590193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roghmann MC, Siddiqui A, Plaisance K, Standiford H. MRSA colonization and the risk of MRSA bacteraemia in hospitalized patients with chronic ulcers. J Hosp Infect. 2001;47(2):98–103. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kollef MH, Morrow LE, Niederman MS, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment patterns among patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129(5):1210–1218. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson DJ, Chen LF, Schmader KE, et al. Poor functional status as a risk factor for surgical site infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(9):832–839. doi: 10.1086/590124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agbaht K, Lisboa T, Pobo A, et al. Management of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit: does trauma make a difference? Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(8):1387–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perl TM, Cullen JJ, Wenzel RP, et al. Intranasal mupirocin to prevent postoperative Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(24):1871–1877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh TJ, Standiford HC, Reboli AC, et al. Randomized double-blinded trial of rifampin with either novobiocin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization: prevention of antimicrobial resistance and effect of host factors on outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(6):1334–1342. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wendt C, Schinke S, Wurttemberger M, Oberdorfer K, Bock-Hensley O, von Baum H. Value of whole-body washing with chlorhexidine for the eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(9):1036–1043. doi: 10.1086/519929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simor AE, Phillips E, McGeer A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of chlorhexidine gluconate for washing, intranasal mupirocin, and rifampin and doxycycline versus no treatment for the eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):178–185. doi: 10.1086/510392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buehlmann M, Frei R, Fenner L, Dangel M, Fluckiger U, Widmer AF. Highly effective regimen for decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(6):510–516. doi: 10.1086/588201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones JC, Rogers TJ, Brookmeyer P, et al. Mupirocin resistance in patients colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a surgical intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(5):541–547. doi: 10.1086/520663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harbarth S, Dharan S, Liassine N, Herrault P, Auckenthaler R, Pittet D. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial to evaluate the efficacy of mupirocin for eradicating carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(6):1412–1416. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coello R, Jimenez J, Garcia M, et al. Prospective study of infection, colonization and carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an outbreak affecting 990 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13(1):74–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02026130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang ES, Tan J, Eells S, Rieg G, Tagudar G, Miller LG. Body site colonization in patients with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other types of S. aureus skin infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009 Aug 18; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02836.x. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]