Abstract

Introduction

Molecular and morphological alterations related to carcinogenesis have been found in terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), the microscopic structures from which most breast cancer precursors and cancers develop, and therefore, analysis of these structures may reveal early changes in breast carcinogenesis and etiologic heterogeneity. Accordingly, we evaluated relationships of breast cancer risk factors and tumor pathology to estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression in TDLUs surrounding breast cancers.

Methods

We analyzed 270 breast cancer cases included in a population-based breast cancer case-control study conducted in Poland. TDLUs were mapped in relation to breast cancer: within the same block as the tumor (TDLU-T), proximal to tumor (TDLU-PT), or distant from (TDLU-DT). ER/PR was quantitated using image analysis of immunohistochemically stained TDLUs prepared as tissue microarrays.

Results

In surgical specimens containing ER-positive breast cancers, ER and PR levels were significantly higher in breast cancer cells than in normal TDLUs, and higher in TDLU-T than in TDLU-DT or TDLU-PT, which showed similar results. Analyses combining DT-/PT TDLUs within subjects demonstrated that ER levels were significantly lower in premenopausal women vs. postmenopausal women (odds ratio [OR]=0.38, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.19, 0.76, P=0.0064) and among recent or current menopausal hormone therapy users compared with never users (OR=0.14, 95% CI=0.046–0.43, Ptrend=0.0006). Compared with premenopausal women, TDLUs of postmenopausal women showed lower levels of PR (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.83–0.97, Ptrend=0.007). ER and PR expression in TDLUs was associated with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in invasive tumors (P=0.019 for ER and P=0.03 for PR), but not with other tumor features.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that TDLUs near breast cancers reflect field effects, whereas those at a distance demonstrate influences of breast cancer risk factors on at-risk breast tissue. Analyses of mapped TDLUs may provide information about the sequence of molecular changes occurring in breast carcinogenesis.

Keywords: terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, breast cancer, risk factors, tumor characteristics

Introduction

Breast cancer is an etiologically and biologically heterogeneous disease that can be classified into different molecular subtypes, which likely reflect differences in pathogenesis [1–5]. Multiple studies show that invasive breast cancer tissues and the pre-invasive lesions that surround them often demonstrate similar molecular alterations, suggesting that the latter represent early, more widespread carcinogenic events characteristic of “field effects” [6–9]. Furthermore, molecular and morphological alterations that may be related to carcinogenesis have also been found in terminal ductal units (TDLUs), the “normal” structures from which cancers and their precursors arise [10–11].

Analysis of mRNA expression profiles of microdissected TDLUs surrounding ER positive (ER+) and ER negative (ER−) breast cancers demonstrate characteristic differences similar to those found in ER+ and ER- invasive cancers, suggesting early divergence in the pathogenesis of these tumor types [10]. Similarly, studies have found that ER expression is higher in TDLUs in breasts containing cancers compared with those that are benign [12–13]. In addition, retrospective cohort data demonstrate that the degree of TDLU involution in biopsies diagnosed as benign breast disease is inversely related to risk of developing breast cancer [14]. Finally, we have shown in age-adjusted analyses that levels of TDLU involution in tissues surrounding luminal cancers are greater than those associated with basal-like cancers [15], suggesting that morphological appearances of benign tissues represent markers of etiological heterogeneity. Thus, we hypothesize that morphological and molecular changes in TDLUs may represent intermediate endpoints along one or more pathways of breast carcinogenesis.

In this study, we assessed whether relationships between breast cancer risk factors and pathological characteristics of invasive breast cancers were related to ER and PR expression in TDLUs surrounding breast cancers included in a population-based case-control study conducted in Poland. We hypothesize that analysis of TDLUS will provide insights into early carcinogenic events, which might be obscured in invasive breast cancer tissues secondary to complex molecular alterations occurring after tumor development.

Methods

Study population

The current analysis was conducted using data and specimens collected in a population-based breast cancer case-control study conducted in Warsaw and Łodz, Poland from 2000 to 2003, as previously described [16]. Briefly, the study included 2,386 cases between the ages of 20 and 74 years diagnosed pathologically with incident in situ or invasive breast carcinoma and 2,502 randomly selected population-based control subjects, frequency-matched to cases on city and age in 5-year categories. The study was approved by the National Cancer Institute and local Institutional Review Boards in Poland.

Risk Factor Assessment

Breast cancer risk factor data was collected through a personal interview [16–17]. Factors evaluated included education, age at menarche, age at menopause, parity, breastfeeding, measured body mass index (BMI), age at first full-term birth, smoking, alcohol drinking, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) use among postmenopausal women; and family history of breast cancer. Serum estradiol and progesterone levels were measured in a subset of Polish cases who donated blood prior to treatment and were not currently using exogenous hormones using standard procedures (Quest Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA). Among premenopausal women, the phase in the menstrual cycle (follicular [<day 11], periovulatory [day 11–16], luteal (day>17]) at blood collection and tissue removal was determined for a subset of cases when the date of the last or start of the next menstrual period was available.

Tissue samples

At the time of routine pathological processing, up to three tissue samples for research were collected and routinely prepared as formalin fixed paraffin embedded blocks, including a sample of tumor (T) and two samples of “grossly” benign tissues from peritumoral (PT; adjacent to but not touching the tumor) and distant aspects of the surgical specimens (DT; at the periphery of the specimen). To prepare a TDLU tissue microarray, we microscopically identified TDLUs in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections, avoiding TDLUs that were extremely small, intermingled with adipose tissue or near the edge of the tissue within the block. Prior work showed that these TDLUs are difficult to array [18]. TDLUs showing luminal dilatation, ductal hyperplasia or calcifications were classified as benign breast disease, and therefore, were not targeted. Tumor size, histologic type, grade, and axillary lymph node status was assessed via clinical reports and independent review (M.E.S) [16].

Construction of tissue microarrays (TMAs) and assessment of ER and PR levels in TDLUs and cancers

Using the location of TDLUs in H&E stained sections as a guide, we removed target TDLUs with a 1.5-mm-diameter core from donor blocks obtained at various distances from the breast cancers: within the same block as the tumor (T); within a tumor-free block adjacent to the tumor (PT) or within a block distant from the tumor (DT). Within a single tissue block (DT, PT, or T), up to three areas containing TDLUs were cored and transferred to a recipient paraffin block as previously described to create the TDLU TMA [18]. TMAs constructed for 270 cases were immunohistochemically stained for ER and PR as previously described [18] and digitized via whole-slide scanning with 20× objective using an Aperio CS instrument (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). We assessed marker expression using two approaches. First, the percentage (0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 20%…100%) of tumor cells with positive staining and the average staining intensity (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, and 3 = strong) were recorded for each marker by visual review (M.E.S.). Combined scores were obtained by multiplying the percentage of cells stained by intensity (ranging from 0 to 3). Second, ER and PR levels were assessed via interactive image analysis of visually demarcated TDLUs (Aperio Technologies) to obtain a quantitative score for each marker using an algorithm designed to approximate visual interpretations. The algorithm was developed to provide a more continuous, standardized objective measure of immunohistochemical staining. Since the staining intensity of ER or PR was highly correlated between TDLU cores (median Spearman correlation coefficient=0.66, p<0.0001), we averaged results across TDLUs within a single tissue block. We used a weighted average to combine scores across multiple TDLUs on each core by multiplying the percentage of nuclei stained with each intensity category (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, and 3 = strong) by intensity score. Scores obtained from the pathologist’s reading and image analysis (ranging from 0 to 3) showed strong correlation (r>0.7, P < 0.0001 for all tissue blocks and both markers), therefore, we used the image analysis derived scores in subsequent analyses.

Breast cancer tissues from women with identifiable TDLUs were included in the same TMAs and scored using identical approaches to facilitate comparisons. This analysis includes a subset of tumors that have been previously evaluated for expression of multiple immunohistochemical markers [17, 19].

Statistical analyses

We used Spearman correlation (overall comparison) and Wilcoxon signed-rank test (paired samples) to assess whether ER/PR expression in TDLUs varied by whether the TDLU was identified in a T, PT or DT block. ER/PR levels in TDLUs in the T block differed from those in the other blocks of the same cases, whereas expression levels in TDLUs within PT and DT blocks did not differ significantly. Therefore we averaged ER and PR scores for PT and DT blocks in cases in which both blocks were available. We categorized average ER/PR expression levels in TDLUs in PT and DT blocks into tertiles, based on the image analysis scores using the product of intensity and percentage of cells stained. To evaluate relationships between breast cancer risk factors and tumor characteristics and the ER/PR levels in TDLUs, we evaluated Chi-square (for categorical variables), Kruskal-Wallis (for continuous variables) tests, and unconditional logistic regression models with ER/PR expression in tertiles as the outcome variable and risk factors/tumor characteristics as the explanatory variables, adjusting for age, specific site in Poland, menopausal status, and phase of the cycle for premenopausal women. We also compared continuous ER/PR expression scores in TDLUs to ER, PR, HER2, EGFR, and CK5 in invasive tumors (dichotomous) using the Kruskal-Wallis test. We used SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) software for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

Our analysis is restricted to 270 women who had identifiable TDLUs that were adequately represented in TMAs. Compared to other Polish cases in the original study, cases included in this analysis were younger (55% <50 years vs. 26% among other Polish cases, P<0.0001), more often premenopausal (59% vs. 22%, P<0.0001), more frequently parous (92% vs. 85%, P=0.002), more frequently used MHT (38% vs. 14%, P<0.0001), and were less often obese (BMI≥30,10% vs. 29%, P<0.0001).

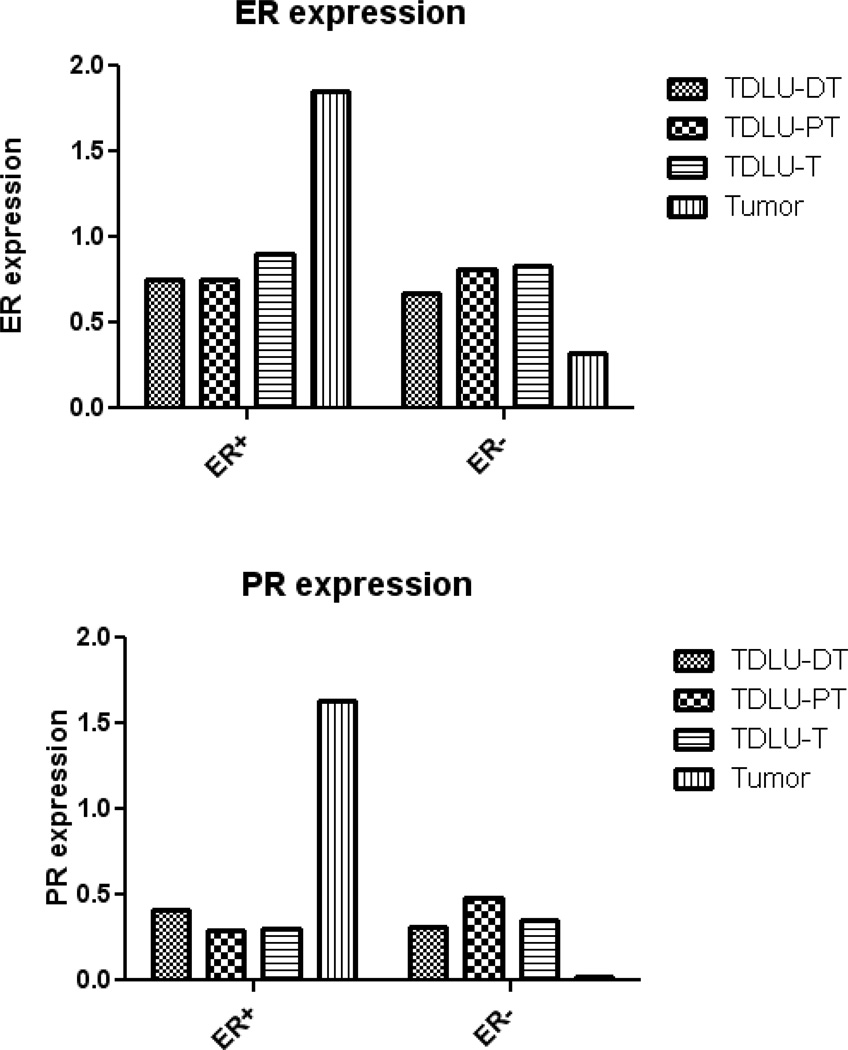

ER/PR expression in TDLUs by proximity to breast cancer across subjects

Since the staining intensity of ER or PR was highly correlated between TDLU cores (median Spearman correlation coefficient=0.66, p<0.0001), we averaged results across TDLUs within a single tissue block. To assess whether ER or PR expression levels in TDLUs varied by distance from an associated breast cancer, we evaluated TDLUs across subjects grouped by location DT (n=117), PT (n=121), and T (n=120) blocks, respectively. In cases with ER-positive tumors, ER expression level in TDLUs was significantly lower in non-tumor blocks (median=0.75 in TDLU-DT and TDLU-PT) compared to TDLU-T blocks (median=0.90) (p=0.03) (Figure 1). Patterns of PR expression in TDLUs of T, PT and DT blocks were similar. In ER positive cases, tumor cells demonstrated higher ER/PR expression than TDLU cells, irrespective of the distance of the TDLU from the tumor (P<0.0001 for ER and PR, Figure 1). In contrast, in cases with ER-negative tumors, ER/PR expression levels were lower in cancer cells compared with luminal cells in TDLUs at any distance from the tumor. ER and PR expression in TDLUs of T, PT and DT blocks were similar (Figure 1). Given that ER/PR expression levels in TDLUs did not differ significantly by the ER status of the associated cancer, we combined data for TDLUs in subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

ER/PR expression in normal terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) in different tissue blocks and in invasive tumors by ER status in associated cancers. DT: tumor-free block distant from the tumor; PT: tumor-free block adjacent to but not touching the tumor; T: tumor block.

Intra-person comparison of ER/PR levels in TDLUs by distance from breast cancer

In contrast to the analysis above in which we combined results by location across subjects, we also compared intra-person ER/PR levels in pairs of TDLUs located at variable distances from the cancers (43 DT and PT pairs, 26 DT and T pairs). ER/PR levels in TDLUs located in different blocks within a single subject showed significant correlations, but only TDLU-T ER expression was significantly correlated with that of invasive cancers (Table 1). Levels of both ER and PR were significantly higher in TDLUs in T compared to DT blocks (P=0.025 for ER and P=0.009 for PR), whereas expression levels were similar in DT and PT blocks for both markers (P=0.90 for ER and P=0.44 for PR). Therefore, we assessed relationships of risk factors and tumor characteristic to levels of ER and PR in TDLUs by combining data for TDLU-DT and TDLU-PT.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation of ER and PR expression levels in TDLUs in different blocks and in invasive cancers.

| All subjects (N=270) | Premenopausal (N=159) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | PR | ER | PR | |||||||||

| TDLU-PT | TDLU-T | Cancer | TDLU-PT | TDLU-T | Cancer | TDLU-PT | TDLU-T | Cancer | TDLU-PT | TDLU-T | Cancer | |

| TDLU-DT | 0.72* | 0.56† | 0.09 | 0.57* | 0.66† | 0.29 | 0.64* | 0.52‡ | 0.11 | 0.52† | 0.68† | 0.32‡ |

| TDLU-PT | 0.59† | 0.11 | 0.63* | −0.12 | 0.57† | 0.08 | 0.46‡ | −0.14 | ||||

| TDLU-T | 0.35† | 0.15 | 0.35‡ | 0.13 | ||||||||

P<0.0001;

P<0.01;

P<0.05.

Relationships of age and breast cancer risk factors to ER/PR expression in TDLU-PT and TDLU-DT

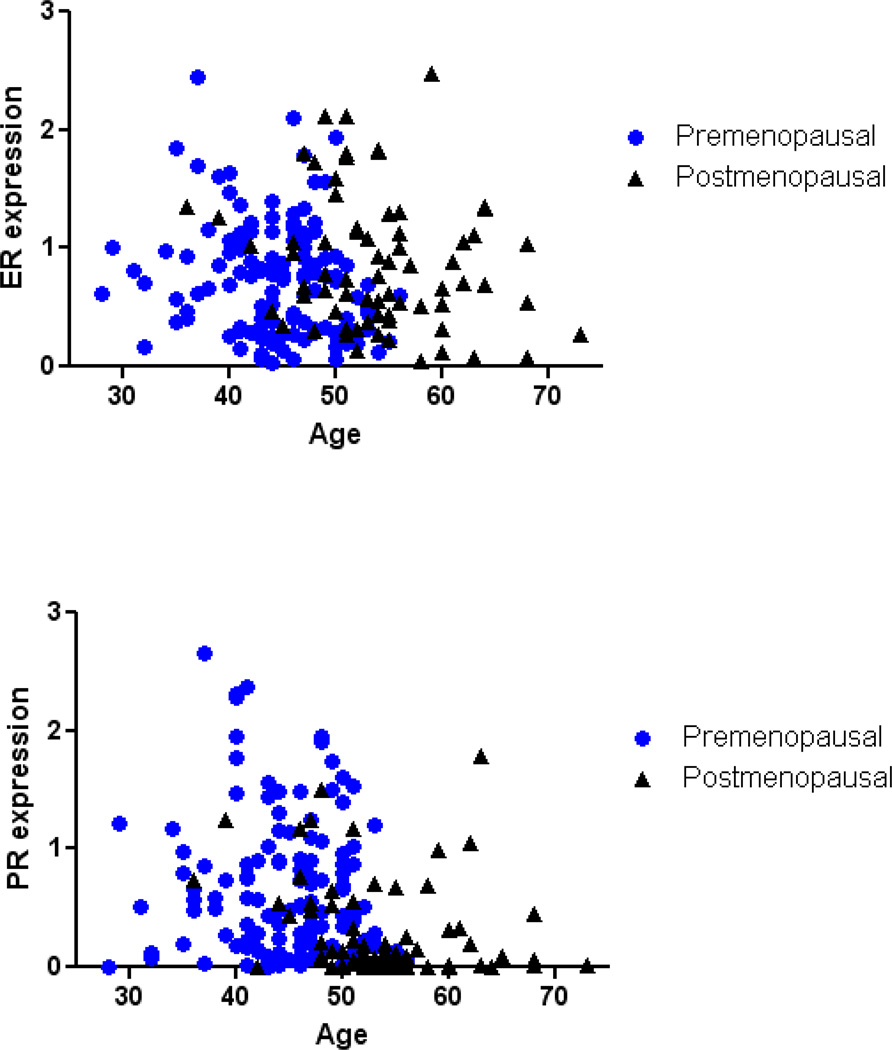

We assessed exposure relationships with ER and PR levels in DT/PT TDLUs in 198 cases. Among all women, age was not significantly related to ER expression in TDLUs (Figure 2, Table 2); however, when both age and menopausal status were included in the model, age was associated with lower ER levels overall (odds ratios [OR]=0.95, 95% confidence intervals [CI]=0.91–0.99, Ptrend=0.026, comparing higher to lower tertiles), among premenopausal women only (OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.89–1.00, Ptrend=0.059), and among postmenopausal women only (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.90–1.02, Ptrend=0.22). However, ER expression in TDLUs was significantly lower in premenopausal than in postmenopausal women (OR=0.38, 95%CI=0.19– 0.76, P=0.0064, Figure 2). Menstrual phase was determined for 88 (55%) of 159 premenopausal cases. ER expression did not vary significantly by cycle phase, although levels were slightly lower in the luteal than in the follicular phase (OR=0.48, 95%CI=0.18, 1.28, P=0.14). Recent or current MHT users had significantly lower ER expression in TDLUs (n= 24 exposed; P=0.0024) and the association remained significant after adjusting for age and study site (OR=0.14, 95% CI=0.046–0.43, Ptrend=0.0006; Table 2).

Figure 2.

ER/PR expression in TDLUs in benign tissue blocks in relation to age and menopausal status.

Table 2.

Relationships of breast cancer risk factors to ER and PR expression in TDLUs among breast cancer cases.

| ER* | PR* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Low (N=65) |

Intermediate (N=66) |

High (N=64) |

P | Low (N=66) |

Intermediate (N=66) |

High (N=66) |

P | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 0.47 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| <50 | 34 | 29.3 | 39 | 33.6 | 43 | 37.1 | 23 | 20.0 | 44 | 38.3 | 48 | 41.7 | ||

| 50–60 | 26 | 41.3 | 21 | 33.3 | 16 | 25.4 | 32 | 48.5 | 18 | 27.3 | 16 | 24.2 | ||

| ≥60 | 5 | 31.3 | 6 | 37.5 | 5 | 31.3 | 11 | 64.7 | 4 | 23.5 | 2 | 11.8 | ||

| Menopausal status | 0.27 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| Pre-menopausal | 45 | 36.0 | 44 | 35.2 | 36 | 28.8 | 25 | 20.2 | 46 | 37.1 | 53 | 42.7 | ||

| Post-menopausal | 20 | 28.6 | 22 | 31.4 | 28 | 40.0 | 41 | 55.4 | 20 | 27.0 | 13 | 17.6 | ||

| Age at menarche | 0.36 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| ≤12 | 18 | 29.0 | 22 | 35.5 | 22 | 35.5 | 13 | 19.7 | 23 | 35.4 | 25 | 38.5 | ||

| 13–14 | 39 | 36.8 | 31 | 29.3 | 36 | 34.0 | 40 | 60.6 | 33 | 50.8 | 34 | 52.3 | ||

| ≥15 | 8 | 32.0 | 12 | 48.0 | 5 | 20.0 | 13 | 19.7 | 9 | 13.8 | 6 | 9.2 | ||

| MHT | 0.002 | 0.38 | ||||||||||||

| No | 3 | 11.1 | 6 | 22.2 | 18 | 66.7 | 14 | 48.3 | 10 | 58.8 | 6 | 75.0 | ||

| Current/recent use | 11 | 45.8 | 8 | 33.3 | 5 | 20.8 | 15 | 51.7 | 7 | 41.2 | 2 | 25.0 | ||

| Serum estradiol (pg/mL) | Mean (N=28) 138.2 | Mean (N=30) 123.0 | Mean (N=25) 85.9 | 0.029 | Mean (N=17) 87.9 | Mean (N=29) 111.6 | Mean (N=39) 126.4 | 0.04 | ||||||

P values were obtained by comparing ER/PR expression in tertiles against variables listed in the table using chi-square test (for categorical variables) and Kruskal-Wallis test (for serum estradiol levels).

Averaged ER and PR expression levels in TDLUs identified from DT and PT blocks.

PR expression in TDLUs was significantly higher among premenopausal women compared to postmenopausal women; 43% of premenopausal women demonstrated the highest tertile of PR in TDLUs versus 18% in postmenopausal women (P<0.0001, Table 2, Figure 2). Older age was associated with significantly lower PR expression in TDLUs overall (OR=0.92, 95% CI=0.89–0.96, Ptrend<0.0001) and among postmenopausal women (OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.83–0.97, Ptrend=0.007) but not among premenopausal women (Figure 2). PR expression in TDLUs among premenopausal women did not vary significantly by the phase of the menstrual cycle; premenopausal women in all cycle phases had significantly higher PR expression compared to postmenopausal women (follicular: OR=3.10, 95%CI=1.26, 7.60, P=0.014; preovulatory: OR=5.51, 95%CI=1.47, 20.70, P=0.011; luteal: OR=2.71, 95%CI=1.07, 6.85, P=0.035). PR expression was inversely related to increasing age at menarche (P=0.019), but this result was not significant after controlling for age and other covariates.

Serum estradiol and progesterone levels were available in 83 cases with ER/PR expression in TDLUs from PT or DT. The overall correlation between estradiol level and marker expression was negative for ER (P=0.029, Kruskal-Wallis test) and positive for PR (P=0.04) (Table 2), however, relationships were not significant after controlling for age and other covariates. Progesterone levels and other breast cancer risk factors assessed were not significantly related to ER/PR expression levels in TDLUs (data not shown).

Relationships of breast cancer pathological features and ER/PR expression in TDLUs

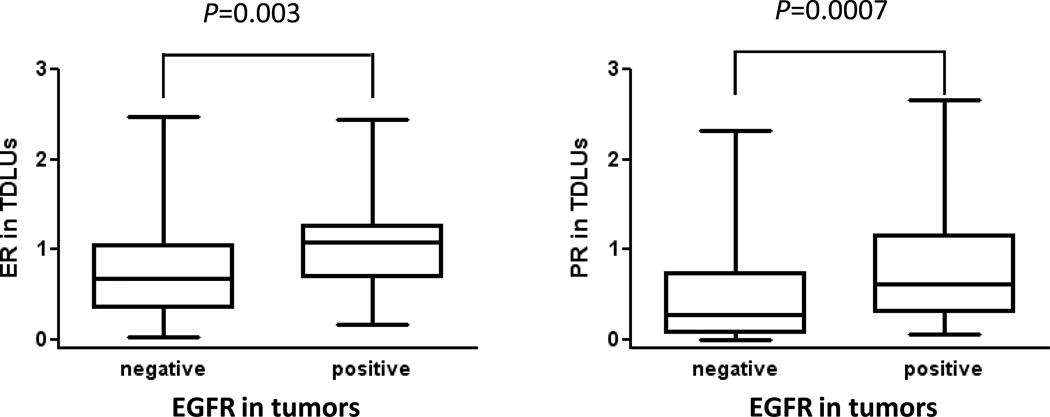

Tumor size, histology, grade, nodal status, and ER/PR status were not significantly associated with ER expression in TDLUs. Larger tumor size (P=0.033) was significantly associated with PR expression in TDLUs, which became borderline significant after the adjustment for age, study site, menopausal status, and other tumor characteristics (OR=1.70, 95% CI=0.93–3.10, Ptrend=0.084, comparing higher to lower tertiles; Table 3). EGFR expression in invasive tumors was directly related to ER and PR expression in TDLUs (P=0.019 for ER and P=0.03 for PR). The association between ER expression in TDLUs and EGFR in tumors remained significant after adjusting for age, study site, menopausal status, and cycle phase (OR=3.50, 95% CI=1.40–8.76, Ptrend=0.0075, comparing higher to lower tertiles). Results from analyses comparing continuous ER/PR expression in TDLUs to EGFR expression in tumors were similar (Kruskal-Wallis test, P=0.003 for ER, P=0.0007 for PR, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Relationships of tumor characteristics and markers to ER and PR expression in TDLUs among breast cancer cases.

| Clinical variables | ER* | PR* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (N=65) |

Intermediate (N=66) |

High (N=64) |

P | Low (N=66) |

Intermediate (N=66) |

High (N=66) |

P | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Histology, N(%) | 0.07 | 0.16 | ||||||||||||

| Ductal | 43 | 33.6 | 37 | 28.9 | 48 | 37.5 | 40 | 30.8 | 46 | 35.4 | 44 | 33.9 | ||

| Lobular | 9 | 39.1 | 10 | 43.5 | 4 | 17.4 | 10 | 40.0 | 6 | 24.0 | 9 | 36.0 | ||

| Mixed | 11 | 36.7 | 10 | 33.3 | 9 | 30.0 | 8 | 26.7 | 13 | 43.3 | 9 | 30.0 | ||

| Other | 2 | 15.4 | 9 | 69.2 | 2 | 15.4 | 8 | 66.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 3 | 25.0 | ||

| Axillary node metastases, N(%) | 0.87 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 35 | 32.1 | 38 | 34.9 | 36 | 33.0 | 34 | 31.2 | 43 | 39.5 | 32 | 29.4 | ||

| Positive | 30 | 35.3 | 27 | 31.8 | 28 | 32.9 | 32 | 36.4 | 23 | 26.1 | 33 | 37.5 | ||

| Tumor grade | 0.18 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 11 | 34.4 | 13 | 40.6 | 8 | 25.0 | 15 | 50.0 | 11 | 36.7 | 4 | 13.3 | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 37 | 37.0 | 35 | 35.0 | 28 | 28.0 | 33 | 31.7 | 33 | 31.7 | 38 | 36.5 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 16 | 26.7 | 17 | 28.3 | 27 | 45.0 | 18 | 29.5 | 20 | 32.8 | 23 | 37.7 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.96 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 35 | 33.0 | 36 | 34.0 | 35 | 33.0 | 40 | 37.0 | 40 | 37.0 | 28 | 25.9 | ||

| > 2 cm | 30 | 34.5 | 28 | 32.2 | 29 | 33.3 | 24 | 27.6 | 25 | 28.7 | 38 | 43.7 | ||

| ER | 0.90 | 0.32 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 26 | 34.2 | 24 | 31.6 | 26 | 34.2 | 21 | 28.0 | 29 | 38.7 | 25 | 33.3 | ||

| Positive | 38 | 33.0 | 40 | 34.8 | 37 | 32.2 | 45 | 37.8 | 36 | 30.3 | 38 | 31.9 | ||

| PR | 0.24 | 0.86 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 23 | 28.0 | 27 | 32.9 | 32 | 39.0 | 30 | 36.1 | 27 | 32.5 | 26 | 31.3 | ||

| Positive | 41 | 37.6 | 37 | 33.9 | 31 | 28.4 | 36 | 32.4 | 38 | 34.2 | 37 | 33.3 | ||

| CK5 | 0.15 | 0.42 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 38 | 36.9 | 32 | 31.1 | 33 | 32.0 | 41 | 38.3 | 35 | 32.7 | 31 | 29.0 | ||

| Positive | 8 | 20.0 | 15 | 37.5 | 17 | 42.5 | 12 | 30.0 | 12 | 30.0 | 16 | 40.0 | ||

| EGFR | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 42 | 35.6 | 41 | 34.7 | 35 | 29.7 | 49 | 40.5 | 28 | 30.1 | 34 | 28.1 | ||

| Positive | 4 | 15.4 | 7 | 26.9 | 15 | 57.7 | 4 | 15.4 | 10 | 40.0 | 13 | 50.0 | ||

| Tumor subtype | 0.09 | 0.16 | ||||||||||||

| Luminal A | 35 | 38.9 | 31 | 34.4 | 24 | 26.7 | 38 | 40.9 | 28 | 30.1 | 27 | 29.0 | ||

| CBP | 5 | 20.0 | 8 | 32.0 | 12 | 48.0 | 5 | 20.0 | 10 | 40.0 | 10 | 40.0 | ||

P values were obtained using chi-square test for differences in frequencies.

Averaged ER and PR expression levels in TDLUs identified from DT and PT blocks.

Figure 3.

ER/PR expression in TDLUs in benign tissue blocks in relation to tumor EGFR expression.

Analysis restricted to premenopausal women

We further restricted our analysis to 159 premenopausal women who did not differ significantly from other premenopausal women in the Polish study in risk factors and tumor characteristics. Associations were similar for ER/PR in TDLUs and different blocks (Table 1) and tumor EGFR (Table 4). Associations for ER in TDLUs and estradiol levels, PR in TDLUs and age at menarche and tumor size showed similar trends but were less significant compared to data obtained from analyses of all subjects (Table 4). ER levels in TDLUs decreased with increasing age, but PR levels were not associated with age among premenopausal women (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Relationships of breast cancer risk factors to ER and PR expression in TDLUs among breast cancer cases among premenopausal women.

| Risk factors | ER* | PR* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (N=45) |

Intermediate (N=44) |

High (N=36) |

P | Low (N=66) |

Intermediate (N=66) |

High (N=66) |

P | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 0.02 | 0.77 | ||||||||||||

| <40 | 3 | 7.2 | 8 | 19.1 | 8 | 19.5 | 5 | 12.5 | 9 | 20.9 | 5 | 12.2 | ||

| 40–50 | 25 | 59.5 | 25 | 59.5 | 31 | 75.6 | 26 | 65.0 | 25 | 58.1 | 28 | 68.3 | ||

| ≥50 | 14 | 33.3 | 9 | 21.4 | 2 | 4.9 | 9 | 22.5 | 9 | 20.9 | 8 | 19.5 | ||

| Age at menarche | 0.19 | 0.20 | ||||||||||||

| ≤12 | 12 | 28.6 | 20 | 47.6 | 15 | 36.6 | 11 | 27.5 | 20 | 46.5 | 15 | 36.6 | ||

| 13–14 | 30 | 71.4 | 22 | 52.4 | 26 | 63.4 | 29 | 72.5 | 23 | 53.5 | 26 | 63.4 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.63 | 0.28 | ||||||||||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 19 | 45.2 | 22 | 53.7 | 18 | 43.9 | 22 | 56.4 | 22 | 51.2 | 16 | 39.0 | ||

| > 2 cm | 23 | 54.8 | 19 | 46.3 | 23 | 56.1 | 17 | 43.6 | 21 | 48.8 | 25 | 61.0 | ||

| EGFR | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||||||||||

| Negative | 26 | 86.7 | 27 | 81.8 | 18 | 56.2 | 30 | 88.2 | 23 | 69.7 | 17 | 63.0 | ||

| Positive | 4 | 13.3 | 6 | 18.2 | 14 | 43.8 | 4 | 11.8 | 10 | 30.3 | 10 | 37.0 | ||

| Serum estradiol (pg/mL) | Mean (N=19) 92.4 | Mean (N=28) 117.9 | Mean (N=26) 135.3 | 0.14 | Mean (N=14) 103.9 | Mean (N=24) 117.1 | Mean (N=36) 117.6 | 0.35 | ||||||

P values were obtained by comparing ER/PR expression in tertiles against variables listed in the table using chi-square test (for categorical variables) and Kruskal-Wallis test (for serum estradiol levels).

Averaged ER and PR expression levels in TDLUs identified from DT and PT blocks.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that ER and PR expression is higher in ER positive breast cancer cells than in luminal epithelial cells of TDLUs and higher in TDLUs adjacent to to these tumors as compared with TDLUs further away. These findings suggest that ER/PR expression in TDLU-T may reflect field effects surrounding breast cancer, as has been shown for other molecular markers [6, 9, 20]. Our observations that TDLU-PT and TDLU-DT showed similar levels of ER and PR levels within a subject, and that these markers demonstrated specific relationships with age and other systemic factors, suggest that these associations may reflect the influences of these exposures on normal breast tissue prior to cancer development. Thus, we hypothesize that analyses of topographically mapped TDLUs may provide information about the sequences of events in breast carcinogenesis. However, further studies are needed to confirm these results and to determine whether various ER/PR expression levels in normal breast epithelium reflect etiologic differences pre-dating and potentially contributing to breast carcinogenesis or a secondary influence of tumor growth on surrounding benign tissues.

We found that ER levels in PT/DT TDLUs were higher among postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women, likely reflecting up-regulation of receptor expression in response to decreased levels of ligand. Similarly, prior studies showed that ER expression in TDLUs of cancer-free women was higher among older women, most likely reflecting an effect of menopause, rather than age per se [21–22]. Another study reported that circulating estradiol levels and ER expression in normal epithelium were inversely related among women with benign breast disease; however, among women with breast cancer, this relationship was not found [23]. Although we found that ER levels in TDLUs were higher after menopause when we modeled age and menopause jointly, we found that increasing age was related to lower ER levels in PT/DT TDLUs among both premenopausal and postmenopausal women, whereas TDLU-T showed the opposite association. Our observed age associations may represent a chance finding or that age, menopausal status and proximity of TDLUs to breast cancer produce complex influences on TDLU ER levels. Further analyses of this question are needed.

In our study, menstrual phases were determined from only a subset of cases, but our results are generally consistent with previous findings that ER expression in TDLUs is lower in the luteal than in the follicular phase, whereas PR levels are similar [24–26]. In contrast, one prior report found that ER expression differed between women with breast cancer and those with benign disease; specifically, among women with breast cancer, ER expression increased in the latter part of the menstrual cycle [13].

Our analysis showed that PR expression in PT/DT TDLUs is higher among premenopausal women with breast cancer compared to postmenopausal cases. PR levels continued to decrease with increasing age in postmenopausal women. Similarly, PR expression in random fine-needle breast aspirates is reportedly significantly lower among healthy postmenopausal women as compared with premenopausal women [27]. PR is an estrogen-responsive gene [28] and its reduced expression may reflect the decreased levels of circulating estrogen among postmenopausal women [29]. Accordingly, we also observed an expected positive correlation (or association) between serum estradiol levels and PR expression in PT/DT TDLUs, mostly in postmenopausal women who have lower circulating estradiol levels compared to premenopausal women. We found that early onset of menarche was related to higher PR expression in PT/DT TDLUs, but this association was attenuated after age adjustment. Prior data suggest that early age at menarche is associated with higher circulating estradiol levels among postmenopausal controls [29].

Elevated circulating levels of estrogens are associated with increased risk of post-menopausal breast cancer and possibly of premenopausal breast cancer, albeit based on weaker evidence [30]. Estradiol may increase breast cancer risk by binding to ER expressed in normal TDLUs, promoting proliferation and expansion of precancerous cells with unrepaired DNA damage. Data from previous studies demonstrated that high ER content in normal breast epithelium is related to increased breast cancer risk [12–13]. In our study, serum estradiol levels were inversely related to TDLU ER expression, including TDLUs adjacent to tumors. In addition, among recent or current MHT users, we observed that ER levels were lower in PT/DT TDLUs, but not in TDLU-T. Higher PR expression in TDLUs was also associated with larger tumor size, consistent with an estrogenic effect on both normal and cancerous cells.

In contrast to a prior report [31], ER/PR expression in TDLUs and cancer were not significantly related in this analysis. However, we excluded TDLUs that demonstrated proliferative changes, whereas the prior study included all benign epithelium. In fact, the earlier study found better agreement between ER levels in breast cancer and benign proliferative lesions as compared with non-proliferative lesions [31]. In addition, the prior investigation assessed expression in cancer and benign tissues on the same slide, which is most comparable to our comparisons of TDLU-T to cancer, which demonstrated a similar correlation (r2=0.35, P=0.003). Thus, the lack of a positive association between ER levels in DT/PT TDLUs and cancer itself might be expected.

We observed that ER/ PR levels in TDLUs were significantly directly associated with EGFR expression in the cancers, which is of interest given the cross-talk between hormone receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) signaling in breast cancer [32] and that ER can induce expression of EGFR ligands including TGFα and amphiregulin [33–34]. Basal-like breast cancer, in which EGFR is frequently expressed, frequently occurs among younger women [35] who have higher level of circulating estradiol compared to older women. Further studies related to this topic may provide clues about the pathogenesis of basal-like breast cancers.

Strengths of our study include analysis of normal-appearing TDLUs at varying distances from tumors, quantitative measurement of ER and PR in TDLUs and in invasive tumors, and a rich collection of epidemiologic data and tumor characteristics. Although our study is relatively small, it is among the largest exploring relationships between breast cancer risk factors, tumor characteristics and marker expression in TDLUs. However, our results may be biased by the restrictive analysis of women with identifiable TDLUs, who differ from the general study population in age, menopausal status, and parity. In addition, the evaluation of a limited number of TDLUs per block or per subject undoubtedly contributed to less accurate evaluation of marker expression than exhaustive analysis of large amounts of tissue; however, this misclassification would likely have been non-differential with respect to tumor type or risk factors and therefore would have biased results towards the null. In addition, our analysis of TDLUs that were included in tissue microarrays showed similar ER/PR expression levels in different TDLUs within a single tissue block and between TDLU-PT and TDLU-DT blocks. Another limitation of our study is that we cannot distinguish whether ER/PR expression levels in normal TDLUs influence breast cancer risk or reflect the influence of tumor on the surrounding benign breast because our analyses used surgical specimens removed from women with breast cancer. However, the similarity of the expression levels in samples proximal and distal from the tumor may weaken this argument because other field effects are more pronounced in close proximity to cancer [7].

In summary, our findings suggest that analysis of marker expression in TDLUs may provide additional information about etiologic heterogeneity, early events in breast carcinogenesis and field effects surrounding breast cancer. Future evaluations using optimized methods to assess markers related to fundamental processes in carcinogenesis such as proliferation, cell cycling and apoptosis in combination with ER/PR status may extend these findings. If fruitful, such research might contribute to identifying intermediate endpoints for breast cancer that would be useful in prevention studies and could have implications for assessing risk of local recurrences.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, DCEG (an Intramural Research Award to Dr. X.R. Yang). We thank Dr. David Rimm and Yale Pathology Tissue Service for their help in making tissue microarrays.

Ethical standards:

The study was approved by the National Cancer Institute and local Institutional Review Boards in Poland. All experiments comply with the current US laws.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, Deng S, Johnsen H, Pesich R, Geisler S, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, Speed D, Lynch AG, Samarajiwa S, Yuan Y, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hazra A, Baer HJ, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Marotti J, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Traditional breast cancer risk factors in relation to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:159–167. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1702-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham K, de las Morenas A, Tripathi A, King C, Kavanah M, Mendez J, Stone M, Slama J, Miller M, Antoine G, et al. Gene expression in histologically normal epithelium from breast cancer patients and from cancer-free prophylactic mastectomy patients shares a similar profile. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1284–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan PS, Venkataramu C, Ibrahim A, Liu JC, Shen RZ, Diaz NM, Centeno B, Weber F, Leu YW, Shapiro CL, et al. Mapping geographic zones of cancer risk with epigenetic biomarkers in normal breast tissue. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6626–6636. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trujillo KA, Hines WC, Vargas KM, Jones AC, Joste NE, Bisoffi M, Griffith JK. Breast field cancerization: isolation and comparison of telomerase-expressing cells in tumor and tumor adjacent, histologically normal breast tissue. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1209–1221. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heaphy CM, Griffith JK, Bisoffi M. Mammary field cancerization: molecular evidence and clinical importance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:229–239. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham K, Ge X, de Las Morenas A, Tripathi A, Rosenberg CL. Gene expression profiles of estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast cancers are detectable in histologically normal breast epithelium. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:236–246. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKian KP, Reynolds CA, Visscher DW, Nassar A, Radisky DC, Vierkant RA, Degnim AC, Boughey JC, Ghosh K, Anderson SS, et al. Novel breast tissue feature strongly associated with risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5893–5898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan SA, Rogers MA, Obando JA, Tamsen A. Estrogen receptor expression of benign breast epithelium and its association with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:993–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan SA, Rogers MA, Khurana KK, Meguid MM, Numann PJ. Estrogen receptor expression in benign breast epithelium and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:37–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milanese TR, Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, Pankratz VS, Degnim AC, Vachon CM, Reynolds CA, et al. Age-related lobular involution and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang XHR, Figueroa JD, Falk RT, Zhang H, Pfeiffer RM, Hewitt SM, Lissowska J, Peplonska B, Brinton L, Garcia-Closas M, Sherman ME. Analysis of terminal duct lobular unit involution in luminal A and basal breast cancers. Breast Cancer Research. 2012:14. doi: 10.1186/bcr3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Closas M, Brinton LA, Lissowska J, Chatterjee N, Peplonska B, Anderson WF, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Bardin-Mikolajczak A, Zatonski W, Blair A, et al. Established breast cancer risk factors by clinically important tumour characteristics. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:123–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang XR, Sherman ME, Rimm DL, Lissowska J, Brinton LA, Peplonska B, Hewitt SM, Anderson WF, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Bardin-Mikolajczak A, et al. Differences in risk factors for breast cancer molecular subtypes in a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:439–443. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang XR, Charette LA, Garcia-Closas M, Lissowska J, Paal E, Sidawy M, Hewitt SM, Rimm DL, Sherman ME. Construction and validation of tissue microarrays of ductal carcinoma in situ and terminal duct lobular units associated with invasive breast carcinoma. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2006;15:157–161. doi: 10.1097/01.pdm.0000213453.45398.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman ME, Rimm DL, Yang XR, Chatterjee N, Brinton LA, Lissowska J, Peplonska B, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Zatonski W, Cartun R, et al. Variation in breast cancer hormone receptor and HER2 levels by etiologic factors: a population-based analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1079–1085. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripathi A, King C, de la Morenas A, Perry VK, Burke B, Antoine GA, Hirsch EF, Kavanah M, Mendez J, Stone M, et al. Gene expression abnormalities in histologically normal breast epithelium of breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1557–1566. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker RA, Cowl J, Dhadly PP, Jones JL. Oestrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor and oncoprotein expression in non-involved tissue of cancerous breasts. The Breast. 1992:2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shoker BS, Jarvis C, Sibson DR, Walker C, Sloane JP. Oestrogen receptor expression in the normal and pre-cancerous breast. J Pathol. 1999;188:237–244. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199907)188:3<237::AID-PATH343>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan SA, Sachdeva A, Naim S, Meguid MM, Marx W, Simon H, Halverson JD, Numann PJ. The normal breast epithelium of women with breast cancer displays an aberrant response to estradiol. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:867–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battersby S, Robertson BJ, Anderson TJ, King RJ, McPherson K. Influence of menstrual cycle, parity and oral contraceptive use on steroid hormone receptors in normal breast. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:601–607. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markopoulos C, Berger U, Wilson P, Gazet JC, Coombes RC. Oestrogen receptor content of normal breast cells and breast carcinomas throughout the menstrual cycle. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1349–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6633.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soderqvist G, von Schoultz B, Tani E, Skoog L. Estrogen and progesterone receptor content in breast epithelial cells from healthy women during the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:874–879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee O, Helenowski IB, Chatterton RT, Jr, Jovanovic B, Khan SA. Prediction of menopausal status from estrogen-related gene expression in benign breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:1067–1076. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz KB, Koseki Y, McGuire WL. Estrogen control of progesterone receptor in human breast cancer: role of estradiol and antiestrogen. Endocrinology. 1978;103:1742–1751. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-5-1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Roddam AW, Helzlsouer KJ, Alberg AJ, Rollison DE, Dorgan JF, Brinton LA, Overvad K, et al. Circulating sex hormones and breast cancer risk factors in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of 13 studies. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:709–722. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hankinson SE, Eliassen AH. Circulating sex steroids and breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. Horm Cancer. 2010;1:2–10. doi: 10.1007/s12672-009-0003-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith FB, Puerto CD, Sagerman P. Relationship of estrogen and progesterone receptor protein levels in carcinomatous and adjacent non-neoplastic epithelium of the breast: a histopathologic and image cytometric study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;65:241–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1010637106174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R. Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:217–233. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saeki T, Cristiano A, Lynch MJ, Brattain M, Kim N, Normanno N, Kenney N, Ciardiello F, Salomon DS. Regulation by estrogen through the 5'-flanking region of the transforming growth factor alpha gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1955–1963. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-12-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;19:183–232. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00144-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narod SA. Breast cancer in young women. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:460–470. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]