Abstract

Whole genome sequencing studies have recently identified a quarter of cases of the rare childhood brainstem tumour diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) to harbour somatic mutations in ACVR1. This gene encodes the type I BMP receptor ALK2, with the residues affected identical to those which, when mutated in the germline, give rise to the congenital malformation syndrome fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), resulting in the transformation of soft tissue into bone. This unexpected link points towards the importance of developmental biology processes in tumorigenesis, and provides an extensive experience in mechanistic understanding and drug development hard-won by FOP researchers to paediatric neuro-oncology. Here we review the literature in both fields and identify potential areas for collaboration and rapid advancement for patients of both diseases.

Keywords: Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, ACVR1, ALK2, development, BMP

INTRODUCTION

Recent sequencing of the whole genome or coding regions (exome) of cancer cells has provided an unprecedented level of insight into the biological processes underlying the development of numerous tumour types(1, 2). Such approaches have shown a remarkable ability to spring surprises, few more so than in the field of paediatric neuro-oncology. Numerous childhood brain tumours have been found to be driven by a diverse series of unexpected genetic and epigenetic processes which differ substantively from adult cancers, with medulloblastoma(3-5), ependymoma(6, 7) and glioma(8, 9) now known to comprise a varied series of sub-entities defined by age, anatomical location, and biology. These insights likely reflect unique origins of these tumours, and highlight the important interface of developmental biology and cancer. Here we discuss a novel link between these processes suggested by the remarkable discovery of mutations present somatically in a subset of lethal childhood brainstem tumours, which when found in the germline give rise to a rare congenital malformation syndrome of soft tissue. What can cancer researchers studying diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma learn from the experience of the fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva field?

DIFFUSE INTRINSIC PONTINE GLIOMA (DIPG)

Although considerably less frequent than histologically similar lesions occurring in adults, high grade gliomas in children represent a major unmet need in clinical neuro-oncology(10). The identification of specific molecular subgroups of these tumours linked to anatomical location and age of incidence(11), and marked by specific gene mutations(8), has strengthened the contention from earlier molecular profiling studies(12) that they harbour unique biology and disease origin(13). An unusual high grade glioma variant restricted to the paediatric setting is diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a brainstem lesion arising in the ventral pons at a peak age of incidence of 6-7 years (Figure 1A). These tumours are universally fatal, with a median overall survival of 9-12 months(10). DIPGs are diffusely infiltrating, and although may harbour regions of lower grade histology, are largely indistinguishable from WHO grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) of the cerebral cortex. Efforts to improve survival in these children have thus far failed – surgical resection of these tumours is not possible due to their anatomical location and clinical trials based upon promising targets from the adult GBM literature have shown no benefit(14).

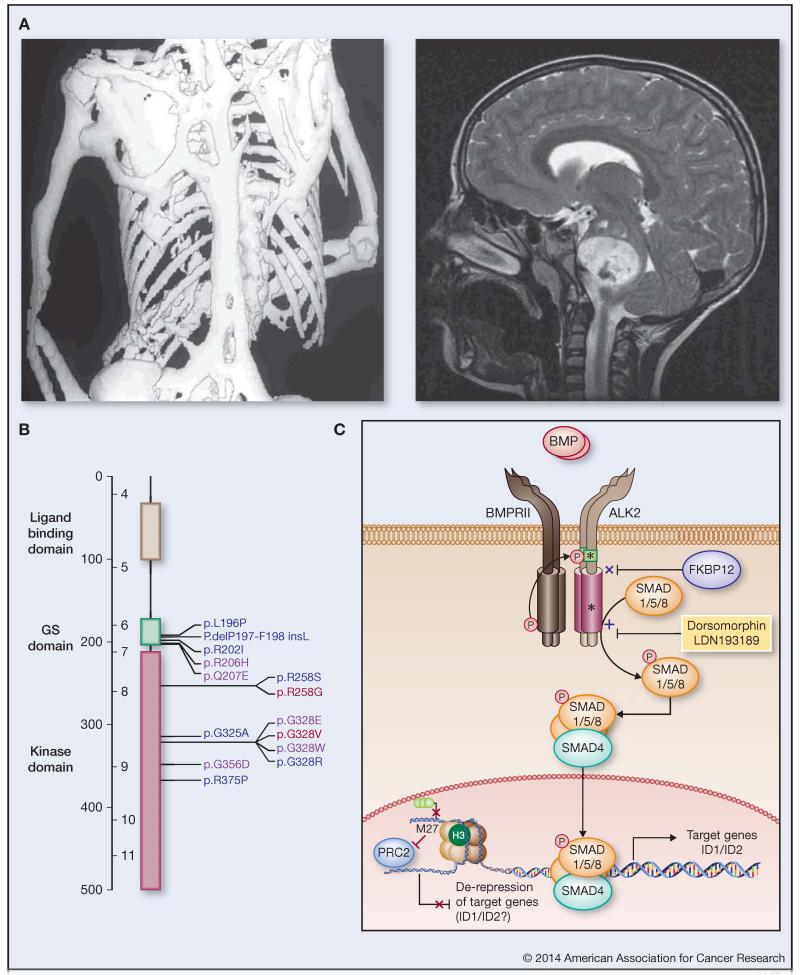

Figure 1. ACVR1 mutations link FOP and DIPG.

(A) Left: Dorso-ventral computed tomography (CT) scan image showing extensive heterotopic bone formation in the skeletal muscles of an aged individual with FOP. (Courtesy of James T. Triffitt, Martyn Cooke and Margot Rintoul). Right: T2 weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of an individual with DIPG at time of diagnosis (Courtesy of Darren Hargrave) (B) Schematic representation of ACVR1 mutations in FOP and DIPG. Protein structure is given highlighting ligand binding (grey), GS (green) and kinase (purple) domains. Amino acid substitutions identified to date in FOP (blue), DIPG (red) or both diseases (purple) are labelled. (C) Cartoon representing a simplified BMP/ALK2 signalling pathway. ALK2 is a type I BMP receptor which dimerises, and upon ligand binding forms a heteromeric complex with two type II receptors (e.g. BMPRII), which themselves phosphorylate the ALK2 GS domain. Mutations (yellow stars) in either the GS or kinase domains inhibit interactions with the negative regulator FKBP12 and enhance recruitment and phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8. Both types of mutation therefore confer constitutive pathway activation as evidenced by increased expression of transcriptional targets of the SMAD1/5/8 and SMAD4 complex in the nucleus. Small molecules such as dorsomorphin and LDN-193189 may be useful therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting the activation of this pathway. ACVR1 mutations co-segregate in DIPG with histone H3.1 K27M mutations, which enhance transcription via disruption of trimethylated lysine 27 interactions with the repressive PRC2 complex. This de-repression of gene expression may include common targets with SMAD signalling including ID1 and ID2.

In order to improve this dismal situation, efforts have focussed on collecting tumour material for detailed molecular analysis. In Europe, the reintroduction of stereotactic biopsy procedures in typical DIPG cases has been pioneered with low morbidity and mortality(15). Elsewhere, rapid autopsy protocols have been opened to obtain tumour material post-mortem(16), as Review Boards have been reluctant to allow biopsies in all but atypical cases due to the requirement only for imaging and a short clinical history for the diagnosis of DIPG(17). Use of such material has provided evidence for distinct DNA copy number and gene expression profiles of DIPG compared to non-brainstem paediatric and adult GBM(18, 19), and more recently, the identification of highly recurrent and selective mutation in genes encoding the histone variants H3.3 (H3F3A) and H3.1 (HIST1H3B)(9). These mutations were initially found in 60% and 18% of cases respectively, and resulted in an amino acid substitution conferring a change of lysine to methionine at position 27 on the histone tail (K27M). Remarkably, such mutations have not been identified in any other cancer type, but are also found in approximately 50% of thalamic GBM(8, 11), an anatomical location generally restricted to children, hinting at a common origin of these tumours and DIPG. Although targeting only one of the many genes encoding histone H3 proteins, the mutation exerts a powerful transdominant negative on cellular H3K27 trimethylation(20), a post-translational modification which usually binds the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to repress gene transcription. K27M mutant tumours consequently have distinct gene expression patterns(21) and global hypomethylation(22), in addition to a restricted age of onset and poor clinical outcome(23). Although this mutation clearly represents a fundamental genetic driver in DIPG, it is currently unclear how to directly target K27M tumours therapeutically.

Recently, four independent studies have been published which apply whole genome or exome sequencing to a collectively large series of DIPG biopsy and autopsy specimens, and have begun to shed light on the wider genetic background against which these H3 K27M mutations are found, providing novel targets for desperately needed treatments. These data, from groups in Paris/London(24), Toronto/Duke(25), St Jude(26) and Montreal/Boston(27) comprise data from a total of 195 DIPGs, representing a remarkable series of collaborative efforts worldwide in this rare disease. Common themes to emerge from these studies include a relatively low mutation rate for such an aggressive tumour (0.8-0.9 mutations per megabase)(24, 26); recurrent alterations in the PI3-kinase (40-68% cases) and p53 pathways (57-76% cases); and a prevalence of mutations in genes encoding chromatin modifiers (26-30% cases)(24-27).

Most strikingly, however, was the unexpected identification of the most recurrently mutated gene in DIPG after the histone variants, ACVR1. This gene, encoding the receptor serine/threonine kinase ALK2, was found to harbour non-synonymous heterozygous somatic mutations in 46/195 (24%) cases at five specific residues(24-27) (Figure 1B). Patients harbouring ACVR1 mutations were predominantly female (approx. 2:1), and had a younger age of onset (approx. 5 years) and longer overall survival time (approx. 15 months) compared with wild-type tumours(24, 26, 27). ACVR1 mutations also strongly co-segregated with K27M mutations in the gene encoding histone H3.1 (HIST1H3B), which themselves are now reported to represent an accumulated 22% of DIPG(24-27). These tumours were also largely TP53 wild-type (90%), and harboured additional alterations in the PI3-kinase pathway (56%)(24-27). The specific base changes in ACVR1 conferred seven different amino acid substitutions, namely R206H (9/46, 20%), Q207E (1/46, 2%), R258G (6/46, 13%), G328E (11/46, 24%), G328V (13/46, 28%), G328W (2/46, 4%) and G356D (4/46, 9%)(24-27). These mutations are located in the glycine-serine rich (GS) (R206H, Q207E) or protein kinase (R258G, G328E/V/W, G356D) domains, with more than half (26/46, 57%) occurring at the glycine at position 328. These mutations appear to be remarkably specific for DIPG – the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database(28) version 68, lists only 18 confirmed somatic ACVR1 mutations in 9170 tumours (0.2%), with only a single amino acid substitution in common with DIPG (a case of hepatocellular carcinoma with G328V). It is worth noting however a further series of three endometrial carcinomas with R206H mutations for whom no matched normal DNA sequence was available. These specific alterations are important, as most remarkably of all, the somatic mutations observed in DIPG are the same as those found in the germline of patients with the congenital malformation syndrome fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP).

FIBRODYSPLASIA OSSIFICANS PROGRESSIVA (FOP)

FOP is an autosomal dominant disorder of skeletal malformation and disabling heterotopic ossification (Figure 1A) that arises in 1 in 1,500,000 live births due to sporadic germline mutations in ACVR1(29). All five sites of mutation newly described in DIPG are also found in cases of FOP, as well as a further five sites across the GS and kinase domains of the encoded ALK2 protein (Figure 1B)(30, 31). Some 95% of FOP cases harbour the recurrent GS domain mutation R206H (c.617G>A), in contrast to the high proportion of ALK2 kinase domain mutations in DIPG(31). Perhaps as a result of this bias, two specific amino acid substitutions found in DIPG samples, R258G and G328V, have yet to be observed in FOP patients(24, 25, 27, 32).

Classical cases of FOP harbouring the R206H mutation may be diagnosed at birth by a signature malformation of the great toes(31). Ectopic bone formation in muscle, tendons and ligament is typically observed by 5 years and progresses to restrict joint movement, such that most individuals are confined to a wheelchair by their third decade of life(31). Episodic flare-ups are additionally precipitated by soft tissue injury, viral infection and inflammation which induce painful localised swellings that may resolve or harden into bone(31). Tissue metamorphosis first involves the catabolism of soft tissue before an anabolic phase involving the differentiation of osteogenic progenitor cells. Unfortunately, flare-ups in children are too often misdiagnosed as malignancy, resulting in harmful surgery and devastating post-operative ossification. FOP may ultimately become life threatening in middle age due to thoracic insufficiency(31).

All FOP-associated mutations activate the canonical BMP pathway to varying degrees to promote osteogenic differentiation and endochondral bone formation(30). BMP ligands belonging to the TGF-beta superfamily bind to heteromeric complexes containing two type II receptors and two type I receptors(33). Type II receptors in this complex activate the type I receptors by phosphorylating their intracellular GS domain, which in turn allows the type I receptors to recruit and phosphorylate the substrate proteins SMAD1/5/8(33) (Figure 1C). These receptor-associated SMADs (R-SMADs) then assemble with SMAD4 and migrate to the nucleus where they bind the promoters of BMP target genes, including ID1-3, SMAD6, SMAD7, SNAIL and HEY1(33). The crystal structure of the GS and kinase domains of ALK2 in complex with the inhibitory protein FKBP12 shows that the disease mutations will break critical side chain interactions that normally stabilise the inactive conformation of the kinase domain(30). The mutant type I receptor therefore partially escapes the normal mechanisms of regulation by FKBP12 and becomes weakly active in the absence of ligand(30). This activation appears sufficient to drive endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), potentially explaining the origin of progenitor cells in FOP lesions with a Tie2+ lineage(34). Furthermore, an Acvr1R206H/+ knock-in mouse displays classical FOP demonstrating that this single mutation is the causative factor(35).

In contrast to FOP, the assessment of the functional significance of ACVR1 in the context of DIPG has thus far been limited(24-27). The early consensus is of these somatic mutations conferring, to varying degrees, a weakly activated BMP signalling pathway, as assessed by transfecting normal human astrocytes and DIPG patient-derived cultures in vitro, with evidence for increased levels of phospho-SMAD1/5/8 and ID1/ID2 mRNA expression(24-27). It is reported that ACVR1 mutant-transduced Tp53-null mouse astrocytes re-implanted to the mouse pons failed to produce tumours in vivo, suggesting that the additional genetic aberrations found in the human disease (e.g. H3.1 K27M, PI3-kinase) may be required for gliomagenesis(26). Importantly, there appear to be no reported cases of DIPG in FOP patients, although numerous neurological symptoms such as neuropathic pain are observed(36), as well as imaging lesions that are linked to dysmyelination and delayed oligodendroglial commitment, seen in both patients and ACVR1 R206H mouse models(37). Hints at a direct oncogenic role are provided by evidence of ACVR1 mutations conferring an enhanced proliferative capacity(25), and selective ALK2 inhibitors reducing cell viability in vitro(24). The specific association of ACVR1 with mutations in histone H3.1, rather than H3.3, seems to point to the likely differing neurodevelopmental contexts from which these tumours arise. BMPs play a crucial role in brain development(38), and BMP signalling in the context of neural stem cells plays an important role in stem cell maintenance and cell fate, and is known to drive progenitor cells towards an astrocytic differentiation(39). DIPGs with predominantly astrocytic features are reported to have an extended survival compared to the remaining subgroup with pronounced oligodendroglial differentiation(19), and this appears likely to be driven by activated BMP signalling via ACVR1 mutation. Indeed in adult glioblastoma, BMPs have been suggested to act as a pro-differentiation regulator of tumour-initiating, stem-like cells(40). It remains unclear whether the modest pathway activation observed in DIPG cells is playing a similar role in these tumours, or whether non-canonical roles for these mutations can be found in the context of cancer development.

TARGETING ACVR1 IN FOP AND DIPG

There is a desperate need for effective treatments to manage both FOP and DIPG. Surgery is precluded for both conditions and therapeutic antibodies appear unsuitable as the activating mutations found in ALK2 affect only the cytoplasmic portion of the receptor. Much effort has therefore focussed on small molecule inhibitors that can target the intracellular kinase activity of the rogue ALK2 protein. The most advanced kinase inhibitors, including DMH1, ML347, LDN-193189 and LDN-212854, share the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine scaffold of dorsomorphin, which was first identified as a BMP inhibitor by a phenotypic screen in zebrafish(41) and later co-crystallised as an ATP-mimetic inhibitor of ALK2(30). These compounds target the BMP receptors ALK2, ALK3 and ALK6 in the low nanomolar range to inhibit SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation, without affecting the type I TGF-beta receptor ALK5 and the SMAD2/3 pathway. The 5-quinoline substituted compound LDN-212854 shows additional selectivity for ALK2 over other BMP receptors and also inhibits heterotopic ossification in mice at a twice daily intraperitoneal dose of 6mg/kg(42). Improvements in selectivity against the wider kinome have also been observed in a new inhibitor class based on the 2-aminopyridine scaffold of K02288(43). Further pre-clinical development of both compound series is required to identify ALK2 inhibitors suitable for trials in humans. As a proof of principle, specific silencing of the mutant ACVR1 c.617A allele has also been demonstrated in FOP patient cell lines using allele-specific siRNA(44).

Other molecular targets may also hold promise for FOP. Retinoic acid receptor gamma (RAR-γ) agonists inhibit chondrogenesis and thereby block heterotopic bone formation in animal models(45). Similar efficacy has also been achieved in mice using the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist, RP-67580, suggesting a disease dependence on the neuro-inflammatory factor Substance P(46). Indeed, prednisolone and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the current standard care for FOP to mitigate swelling during flare-ps. Whether flare-ups spontaneously resolve or ossify remains unpredictable. Therefore, precise natural history studies are also required in the FOP patient population to provide a statistical measure of drug efficacy.

Despite the head-start afforded by the progress made in FOP, several challenges need to be overcome in order to move forward with ALK2 inhibitors in DIPG. The first and arguably most critical is to develop small molecules with sufficient CNS penetration to reach potentially effective doses in these brainstem tumours. Although GBMs frequently show evidence of a disrupted blood-brain barrier, delivery to the pons may represent an additional hurdle, and DIPGs appear to have a relatively intact vasculature(14). With current ALK2 inhibitors lacking the chemical indicators of efficient CNS penetration, novel medicinal chemistry approaches may be necessary to produce a DIPG-specific compound, although specific models mimicking the blood-brain-tumour barrier in humans are currently lacking. Alternative forms of administration such as convection-enhanced delivery(47) may be required to take advantage of existing chemical series, and clinical trials using this technique in DIPG are still ongoing.

An additional complication is associated with the complicated genetic background present in DIPG compared to the monogenic nature of FOP. The limited in vitro preclinical work in DIPG cells has shown only modest sensitivity to ALK2 inhibitors as single agents(24), and combinatorial approaches additionally targeting other co-segregating somatic alterations such as H3.1 K27M mutations and PI3-kinase activation(24-27) will likely be required. Even then, the inherent intratumoral heterogeneity of DIPG represents a major obstacle to targeted therapy due to the subclonal diversity of these tumours providing the substrate for clonal selection and development of resistance according to evolutionary biology principles(48).

Despite these caveats, there remains optimism that a more thorough understanding of the underlying biology of these tumours afforded by genome-wide profiling will provide clinicians with an enhanced armamentarium of drugs with which to combat these tumours. Owing to the continued dire clinical outcome of children with DIPG, there are significant opportunities for rapid testing of promising approaches within first-line clinical trials, though the rarity of the disease will necessitate a co-ordinated, collaborative approach. With ACVR1 mutant tumours representing around 25% of DIPGs, predictive biomarkers will be key in guiding patients to the most suitable therapy. There is evidence of pathway activation even in the absence of ACVR1 mutation in DIPG(24-27), possibly expanding the patient population who may benefit from ALK2 inhibitors, but also complicating patient stratification. For all potential predictive markers, routine biopsies will likely need to be re-introduced in order to select patients who will most likely benefit from novel agents, a further challenge for the paediatric neuro-oncology community which the unexpected identification of ACVR1 mutations may help to overcome.

CONCLUSIONS

It is becoming increasingly apparent that paediatric brain tumours have their origins during neurodevelopment, and that cross-disciplinary approaches will be necessary to fully understand and leverage the wealth of data from whole genome sequencing studies into improved outcomes for these patients. The surprising link between the seemingly unrelated diseases of DIPG and FOP suggested by common mutations in ACVR1 represents a unique opportunity for collaboration between researchers in disparate fields to fast-track drug development for both entities. Although each disease has its own requirements and obstacles, we ought to be optimistic that our shared experiences, insights and approaches can lead to synergies in tackling the desperate unmet clinical needs of two groups of children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The SGC is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, Genome Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly Canada, the Novartis Research Foundation, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, Takeda, and the Wellcome Trust [092809/Z/10/Z]. KRT, MV and CJ acknowledge funding by the Cancer Research UK Genomics Initiative (A14078), the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Abbie’s Army, The Lyla Nsouli Foundation, the Royal Marsden Hospital Childrens Department Fund and NHS funding to the National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Centres. The authors would like to thank Alan Mackay for informative discussions relating to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1113–20. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones DT, Jager N, Kool M, Zichner T, Hutter B, Sultan M, et al. Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488:100–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, Pomeranz Krummel DA, Auclair D, Bochicchio J, et al. Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations. Nature. 2012;488:106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson G, Parker M, Kranenburg TA, Lu C, Chen X, Ding L, et al. Novel mutations target distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488:43–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, Gu L, Zuyderduyn S, Stutz AM, et al. Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. 2014;506:445–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506:451–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482:226–31. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, et al. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nature genetics. 2012;44:251–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones C, Perryman L, Hargrave D. Paediatric and adult malignant glioma: close relatives or distant cousins? Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2012;9:400–13. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer cell. 2012;22:425–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, Adamowicz-Brice M, Zhang J, et al. Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease. Journal of clinical oncology. 2010;28:3061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturm D, Bender S, Jones DT, Lichter P, Grill J, Becher O, et al. Paediatric and adult glioblastoma: multiform (epi)genomic culprits emerge. Nature reviews Cancer. 2014;14:92–107. doi: 10.1038/nrc3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren KE. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: poised for progress. Frontiers in oncology. 2012;2:205. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roujeau T, Machado G, Garnett MR, Miquel C, Puget S, Geoerger B, et al. Stereotactic biopsy of diffuse pontine lesions in children. Journal of neurosurgery. 2007;107:1–4. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/07/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broniscer A, Baker JN, Baker SJ, Chi SN, Geyer JR, Morris EB, et al. Prospective collection of tissue samples at autopsy in children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cancer. 2010;116:4632–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albright AL, Packer RJ, Zimmerman R, Rorke LB, Boyett J, Hammond GD. Magnetic resonance scans should replace biopsies for the diagnosis of diffuse brain stem gliomas: a report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:1026–9. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199312000-00010. Discussion 9-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paugh BS, Broniscer A, Qu C, Miller CP, Zhang J, Tatevossian RG, et al. Genome-wide analyses identify recurrent amplifications of receptor tyrosine kinases and cell-cycle regulatory genes in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Journal of clinical oncology. 2011;29:3999–4006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puget S, Philippe C, Bax DA, Job B, Varlet P, Junier MP, et al. Mesenchymal transition and PDGFRA amplification/mutation are key distinct oncogenic events in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. PloS one. 2012;7:e30313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, Cordero F, Lin S, Banaszynski LA, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science. 2013;340:857–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1232245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjerke L, Mackay A, Nandhabalan M, Burford A, Jury A, Popov S, et al. Histone H3.3 Mutations Drive Pediatric Glioblastoma through Upregulation of MYCN. Cancer discovery. 2013 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, Hovestadt V, Jones DT, Kool M, et al. Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of gene expression in K27M mutant pediatric high-grade gliomas. Cancer cell. 2013;24:660–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Bouffet E, et al. K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;124:439–47. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0998-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor KR, Mackay A, Truffaux N, Butterfield YS, Morozova O, Philippe C, et al. Recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nature genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buczkowicz P, Hoeman C, Rakopoulos P, Pajovic S, Letourneau L, Dzamba M, et al. Genomic analysis of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas identifies three molecular subgroups and recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations. Nature genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL, Ju B, Li Y, et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nature genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fontebasso AM, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Schwartzentruber J, Nikbakht H, Gerges N, Fiset PO, et al. Recurrent somatic mutations in ACVR1 in pediatric midline high-grade astrocytoma. Nature genetics. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:D945–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Cho TJ, Choi IH, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nature genetics. 2006;38:525–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaikuad A, Alfano I, Kerr G, Sanvitale CE, Boergermann JH, Triffitt JT, et al. Structure of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK2 and implications for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:36990–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, Connor JM, Glaser DL, Carroll L, et al. Classic and atypical fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Human mutation. 2009;30:379–90. doi: 10.1002/humu.20868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital-Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nature genetics. 2014;46:444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmierer B, Hill CS. TGFbeta-SMAD signal transduction: molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:970–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medici D, Shore EM, Lounev VY, Kaplan FS, Kalluri R, Olsen BR. Conversion of vascular endothelial cells into multipotent stem-like cells. Nature medicine. 2010;16:1400–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakkalakal SA, Zhang D, Culbert AL, Convente MR, Caron RJ, Wright AC, et al. An Acvr1 R206H knock-in mouse has fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Journal of bone and mineral research. 2012;27:1746–56. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitterman JA, Strober JB, Kan L, Rocke DM, Cali A, Peeper J, et al. Neurological symptoms in individuals with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Journal of neurology. 2012;259:2636–43. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6562-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kan L, Kitterman JA, Procissi D, Chakkalakal S, Peng CY, McGuire TL, et al. CNS demyelination in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Journal of neurology. 2012;259:2644–55. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furuta Y, Piston DW, Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) as regulators of dorsal forebrain development. Development. 1997;124:2203–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bond AM, Bhalala OG, Kessler JA. The dynamic role of bone morphogenetic proteins in neural stem cell fate and maturation. Developmental neurobiology. 2012;72:1068–84. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, Lamorte G, Binda E, Broggi G, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;444:761–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu PB, Hong CC, Sachidanandan C, Babitt JL, Deng DY, Hoyng SA, et al. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohedas AH, Xing X, Armstrong KA, Bullock AN, Cuny GD, Yu PB. Development of an ALK2-biased BMP type I receptor kinase inhibitor. ACS chemical biology. 2013;8:1291–302. doi: 10.1021/cb300655w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanvitale CE, Kerr G, Chaikuad A, Ramel MC, Mohedas AH, Reichert S, et al. A new class of small molecule inhibitor of BMP signaling. PloS one. 2013;8:e62721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan J, Kaplan FS, Shore EM. Restoration of normal BMP signaling levels and osteogenic differentiation in FOP mesenchymal progenitor cells by mutant allele-specific targeting. Gene therapy. 2012;19:786–90. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimono K, Tung WE, Macolino C, Chi AH, Didizian JH, Mundy C, et al. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-gamma agonists. Nature medicine. 2011;17:454–60. doi: 10.1038/nm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kan L, Lounev VY, Pignolo RJ, Duan L, Liu Y, Stock SR, et al. Substance P signaling mediates BMP-dependent heterotopic ossification. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2011;112:2759–72. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souweidane MM. Editorial: Convection-enhanced delivery for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Journal of neurosurgery Pediatrics. 2014;13:273–5. doi: 10.3171/2013.10.PEDS13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–13. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]