Abstract

Metopic craniosynostosis is a common growth disturbance in the infant cranium, second only to sagittal synostosis. Presenting symptoms are usually of a clinical nature and are defined by an angular forehead, retruded lateral brow, bitemporal narrowing, and a broad-based occiput. These changes create the pathognomonic trigonocephalic cranial shape. Aesthetic in nature, these morphological changes do not constitute the only developmental issues faced by children who present with this malady. Recent studies and anecdotal evidence have also demonstrated that children who present with metopic synostosis may face issues with respect to intellectual and/or psychological development. The authors present an elegant approach to the surgical reconstruction of the trigonocephalic cranium using an in situ bandeau approach.

Keywords: craniosynostosis, metopic, trigonocephaly, suture

In the annals of craniofacial and neurosurgical care, sagittal synostosis is recognized as the most commonly treated synostotic phenomenon. However, for those who see a broad range and high volume of pediatric patients, the early closure of the metopic suture presents as an even more common event. The reason that metopic synostosis is seen as the second (incidence 1:5200)1 most common craniosynostosis2 rests in the fact that the majority of metopic patients present “late” with a small forehead ridge and/or a closed anterior fontanel. As such, these patients do not require any intervention other than parental reassurance. However, there are those patients who do present with significant cranial asymmetry secondary to early closure of the metopic suture. Some of these patients present with an obvious trigonocephalic head shape, while others have more subtle asymmetries due to a combination of early metopic closure combined with significant positional plagiocephaly. In either of these situations, surgical intervention can serve as an effective means of correcting the cranial asymmetries driven by inappropriate growth. Given social and cultural pressures that emphasize beauty, sameness, and symmetry, “looks” may be a sufficient reason to undergo cranial vault remodeling. In the case of metopic synostosis, there exists a slowly growing body of knowledge which seems to indicate that expanding the anterior cranial vault directly enhances cognitive function and ability.3 4 5 6 Although skepticism may exist regarding our ability to assess intellectual development in the first few months of life and the effects that surgery may have on a growing brain, the hallways of medicine and indeed our own offices are rife with anecdotal/clinical evidence of marked intellectual improvement shortly after frontal cranial vault remodeling. Embracing the plastic surgery edict that we, as craniofacial surgeons, are asked to restore form (cranial symmetry) and function (cognitive ability), it is obvious that a clear understanding with regards to the diagnosis and management of metopic synostosis is essential to the health and well-being of our patients.

Clinical Presentation of Trigonocephaly

The severity of the cranial deformity associated with early closure of the metopic is directly predicated upon the timing of suture closure. In general, the earlier the closure of the metopic suture, the more severe is the resultant cranial deformity. To understand the forces at work one must recall that skull growth is driven by brain growth and that up to 70% to 80% of brain/skull growth occurs during the first 18 months of life.7 With this in mind, it is clear that the cranial sutures must accommodate a prodigious amount of growth in a very short period. Thus, any compromise to the growth potential of metopic suture early on in life will have a significant effect on head size and shape because the active growth phase of this suture is very limited. In fact, the metopic suture exhibits an even more limited growth period than the other cranial sutures with some studies demonstrating that the metopic suture is routinely done with growth by 8 months.8 This may account for the frequent presentation of small forehead ridges with little cranial vault asymmetry.

The issue of early closure of the metopic suture is not the sole cause of the classic trigonocephalic or triangular head shape noted in this case of arrested development. Although early closure of the metopic will limit lateral growth of the forehead and create the associated hypotelorism and retruded lateral orbital anatomy, it is the compensatory hypergrowth of the remaining skull sutures that leads to the widened and flattened appearance of the occipital skull. Thus, it is the combined lack of lateral anterior growth and the posterior overgrowth that results in the classic trigonocephalic shape (Figs. 1 2 3 4).

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional computed tomography, apical view, demonstrating the classic trigonocephalic shape of metopic synostosis. Note the anterior ridging indicative of early metopic closure.

Fig. 2.

Planar computed tomography image demonstrating the triangular shape of the cranium.

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional computed tomography, frontal view. Note the bitemporal narrowing and the associated pinching of the lateral supraorbital brow. The orbits are elongated in the craniocaudal dimension.

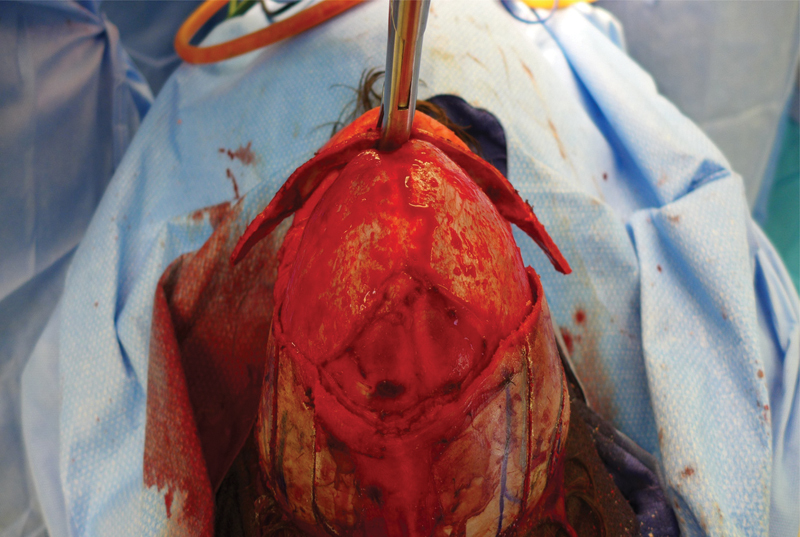

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative presentation of the skull from an apical view.

The classic, triangular head shape associated with early metopic synostosis is fairly easy to identify. Bitemporal narrowing, hypotelorism, and a broad occiput reflect asymmetries that even the novice physician can readily appreciate. Cases can be classified as severe (angulation < 89 degrees), moderate (90–95 degrees), and mild (between 96–103 degrees).9 More difficult to assess is the patient who presents with a mixed diagnosis that we describe as a partially compensated trigonocephaly. This subset of patients presents with two distinct pathological issues. First, is the standard metopic craniosynostosis with the associated limitations of anterior cranial growth and lateral osseous hypoplasia with exposure of the upper lateral orbital contents. The second issue this unique group carries is the additional finding of positional plagiocephaly. The positional plagiocephaly causes one occiput to be pushed forward. The ipsilateral ear and the ipsilateral forehead are also pushed anteriorly. In this setting, the patient presentation is one of hemi-trigonocephaly because the plagiocephalic side is partially compensated by the anterior push associated with the positional plagiocephaly. In many instances, the severity of the unilateral supraorbital retrusion, temporal hollowing, and metopic ridging will necessitate surgical correction of this deformity even though the classic anterior V and cranial triangle are not in evidence.

Clinical Management and Indications for Correction

Single suture craniosynostosis can lead to significantly abnormal head shapes. However, the premature closure of a single suture is generally not associated with microcephaly and/or raised intracranial pressure. With this in mind, no family should be coerced into a surgical solution. Parents should be apprised of the anatomy and pathology involved. A clear overview regarding the shape of the head at initial presentation and the potential for change must be described. If surgery is indicated and the family decides to move forward, an intervention is scheduled in a timely fashion. If the clinical course warrants a more conservative approach, then at a minimum the child should be followed until 12 months of age to ensure satisfactory cranial growth and development. During this time, routine follow-up consisting of comprehensive clinical evaluations and in-depth family discussions regarding cranial development is entertained. In mild cases, reassurance is all that is needed. However, in cases demonstrating significant trigonocephaly, most parents will advocate for early surgical intervention due to concerns related to possible psychological and social issues related to the “different” appearance of the cranium.

Surgical Interventions

Surgical management of craniosynostosis has its origins in the field of neurosurgery. Initial approaches embraced the concept of open strip craniectomy prior to one year of age, after which no further intervention was employed. Although this approach successfully “solved” the sutural growth issue, it did nothing to correct the secondary deformities associated with the abnormal growth patterns that were inherent to the disease.

Today's management of craniofacial anomalies finds its roots in France, where Dr. Paul Tessier daringly pushed past the perceived surgical limitations presented by the craniofacial skeleton. Divining that the skull and the facial bones could be skeletonized, cut, moved, and fixated in any of the three anatomical dimensions, Tessier created a new field of surgery in which art and aesthetics hold an advanced place with respect to managing craniofacial anomalies.10 11 Isolated strip craniectomies were no longer adequate therapy when practitioners such as Marchac, McCarthy, Salyer, and Whittaker1 12 13 14 could do so much more. Conscious of aesthetics, these surgeons endeavored to advance and remodel the supraorbital bar while reshaping the forehead in an effort to solve both the sutural growth issues and to restore normal anatomical form by reshaping the forehead. Although open techniques predicated on bandeau advancement and reshaping became the new standard, the “strip” craniectomy was to see a resurgence due to the efforts of Vicari in 1991,15 and subsequently Jimenez and Barone.16 17 The Jimenez/Barone approach brought two new twists to cranial vault surgery: Jimenez performed the strip using an endoscope and he employed a postoperative molding helmet in an effort to direct the released growth potential into a more appropriate skull shape. The technique shortened operating room time, decreased blood loss, and shortened length of hospitalization, while it yielded better aesthetic results compared with strip craniectomy alone. A relevant caveat, however, is that the approach is age dependent and is best employed prior to 3 to 4 months of age.

Understanding the Deformity

The goal of every plastic surgery case is to reconstruct the anatomy to restore form and function to “normal.” To accomplish this, the surgeon must have a clear understanding of the normal endpoint. Ansel Adams, the famous photographer, described the technique of previsualization when he discussed his process of getting “the shot.” His concept is key to all reconstructive surgical procedures in that the surgeon must have a mental image of what the final outcome is to be if he or she is to successfully craft a solution to the three-dimensional problem presented. In classic metopic synostosis, there are four issues that must be addressed to achieve a symmetric cranial vault.

The acutely angled supraorbital region must be realigned into a more natural “sunglasses” shape.

The acutely angled frontal bone must be reshaped to correct the metopic ridge and to flatten and round the forehead so that it matches the neo-bandeau shape. Frontal bossing, if present, must be corrected.

The anterior parietal bone must be raised cephalad and the curve that transitions the temporal bone to the parietal bone must be moved higher/cephalad on the cranium.

The temporal bone that assumes an anteriorly angled position must be bent outward to correct the unnatural inward angulation, fill the temporal fossa, and accommodate the newly widened bandeau.

Note, that in metopic synostosis the supraorbital bar/bandeau is not displaced at its central point at the nasion. As such, this portion of the bandeau does not need to be cut because it does not need to move. Unmolested by surgical trauma the nasion of the bandeau is allowed to maintain its blood supply, thus enhancing the viability of this critical structure.

Operative Technique

The patient is placed in a supine position on an outrigger headholder, and the incision line is injected with 1% Lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. A zig-zag incision is made through the skin and carried through the galea with a micropoint cautery. Pericranial flaps are raised via a midline release and then they are taken laterally and left attached to the temporalis muscle. The temporalis is dissected to a point below the zygomaticofrontal suture after which the orbits and periorbital regions are completely dissected so that full and unfettered access to the anterior cranium, temporal bone, and orbits is available. The bandeau is marked as is the frontal bone flap. The frontal bone is removed and intracranial dissection is performed. The bandeau is then cut under neurosurgical supervision/protection. The bandeau release is accomplished utilizing a reciprocating saw. The lateral arms are cut horizontally from posterior to anterior, moving up to and through the sphenoid wings. After this, the orbital roof is cut from medial to lateral while the orbital contents and brain are protected by malleable retractors. Any incomplete cuts are finished with an osteotome and the arms of the bandeau are checked for complete release and mobility. The nasion region of the bandeau is not cut and remains attached. Bleeding can be seen at the distal edges of the bandeau arms indicating continuity of the osseous vascular tree. The in situ sphenoid bone is treated with bone wax to prevent bleeding. If the bandeau is thick, demonstrating bilamellar bone, single table partial osteotomies may be made to facilitate bending of the bandeau with the Tessier bone benders. The scoring should be done so that the grooves open radially as bending pressure is applied. Specifically, the lateral arms may require outer table scoring while the nasion region may benefit from grooves placed on the inner table. Once the relaxing grooves are complete, the Tessier bone bender is used to gently flatten the bandeau at the nasion (Fig. 5). This brings the supraorbital rims forward and flares the lateral bandeau arms. Next, the arms of the bandeau are bent back toward the skull so that they form a fairly straight line from the lateral orbital rim backward toward the occiput. A useful concept to have in mind is that the bandeau should roughly assume the shape of a standard pair of sunglasses. The next step in the reconstruction focuses on the temporal region. In the trigonocephalic cranium, temporal bones are angled toward the anterior midline; they must be repositioned to accommodate the widened arms of the bandeau. In an effort to facilitate this temporal bone repositioning, an osteotomy is performed at the junction of the temporal and parietal bones. Using a guarded saw, a straight line osteotomy is made from the posterior cut edge of the frontal bone progressing posteriorly to an area just anterior to the bioccipital prominences. The osteotomy then flairs into a Y configuration around the occipital prominence (Fig. 6). The cuts are performed symmetrically on both sides of the cranium. They are designed to allow for gentle outward greenstick repositioning of the temporal bones. With these maneuvers complete, the arms of the bandeau are advanced and secured into a new wider position bilaterally. The arms are held in place with KLS resorbable plates and rivets (KLS-Martin, Jacksonville, FL).

Fig. 5.

Tessier bone benders applied to the in situ bandeau. Note the flattening of the central supraorbital bandeau and flaring of the lateral arms. The lateral arms will be bent back toward the cranium to create a more natural “sunglasses” shape.

Fig. 6.

A rendering indicating the osteotomy lines that are created at the junction of the temporoparietal bone. These cuts allow the temporal bone to be rotated outward in an effort to meet the newly positioned arms of the bandeau.

Having set the bandeau and temporoparietal regions, the forehead is brought back onto the field. The frontal bone is split into two halves and relaxing osteotomies are performed a la the techniques described by Hendel and Nadell in their seminal paper on projection geometry and stress-reduction.18 Small triangles are then removed from the posterolateral inferior borders of the frontal bones to rock the bone back and correct any frontal bossing that may be present. The two halves are then independently reshaped using bone benders. They are then matched to the neo-bandeau and secured to the construct utilizing 2.0 PDS sutures tied in a figure-of-eight configuration. The osseous reconstruction complete, a high-speed bur is used to reshape the orbits and remove any bony prominences.

The temporalis muscles and pericranium are resuspended with sutures in the pericranium and in the superficial temporal fascia. These fascial stitches have been instrumental in reducing the incidence of postoperative temporal hollowing. The entire construct is irrigated with antibiotic impregnated saline and the incision is closed in layers with absorbable suture.

Conclusion

Metopic synostosis does not garner the volumetric fanfare associated with early sagittal suture closure, but the aesthetic and intellectual risks involved with poor management of this sutural anomaly may be more profound. In modern society, the face plays a critical role in the realm of social interaction and acceptance. Thus, a natural facial form is important, if not critical to personal development. On a parallel and perhaps more important track, our brain, the amazing computer that makes us who we are, may not be able to reach its full potential in the trigonocephalic cranium. Alone, either one of these issues seems sufficient to warrant a surgical intervention. Taken together, it is difficult to ascertain a reason why one would not put forth effort to ameliorate the potential pitfalls associated with no treatment. The in situ bandeau approach presented here is an easily reproducible, highly successful surgical intervention that yields exceptional results (Figs. 7 and 8). Over the past 5 years, we have used this technique in over 80 cases and parents have uniformly been pleased with the aesthetic and intellectual gains garnered with this technique.

Fig. 7.

Pre- and postoperative vertex view; note the rounding of the forehead and the natural line of the temporal region.

Fig. 8.

Pre- and postoperative frontal view; the midline ridge is gone, the forehead is rounded, and the temporal region is full.

References

- 1.Kweldam C F, van der Vlugt J J, van der Meulen J J. The incidence of craniosynostosis in the Netherlands, 1997-2007. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(5):583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Meulen J. Metopic synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28(9):1359–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson F M. Treatment of coronal and metopic synostosis: 107 cases. Neurosurgery. 1981;8(2):143–149. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shillito J Jr, Matson D D. Craniosynostosis: a review of 519 surgical patients. Pediatrics. 1968;41(4):829–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collmann H, Sörensen N, Krauss J. Consensus: trigonocephaly. Childs Nerv Syst. 1996;12(11):664–668. doi: 10.1007/BF00366148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy J G, Epstein F, Sadove M, Grayson B, Zide B. Early surgery for craniofacial synostosis: an 8-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73(4):521–533. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nellhaus G. Head circumference from birth to eighteen years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics. 1968;41(1):106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vu H L, Panchal J, Parker E E, Levine N S, Francel P. The timing of physiologic closure of the metopic suture: a review of 159 patients using reconstructed 3D CT scans of the craniofacial region. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12(6):527–532. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oi S, Matsumoto S. Trigonocephaly (metopic synostosis). Clinical, surgical and anatomical concepts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1987;3(5):259–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00271819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tessier P. [Total facial osteotomy. Crouzon's syndrome, Apert's syndrome: oxycephaly, scaphocephaly, turricephaly] Ann Chir Plast. 1967;12:273–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tessier P, Guiot G, Rougerie J, Delbet J P, Pastoriza J. Ostéotomies cranio-naso-orbito-faciales. Hypertélorisme. Ann Chir Plast. 1967;12(2):103–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchac D. Radical forehead remodeling for craniostenosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61(6):823–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salyer K E. Personal contributions to craniofacial surgery. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg Suppl. 1995;27:19–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitaker L A, Bartlett S P, Schut L, Bruce D. Craniosynostosis: an analysis of the timing, treatment, and complications in 164 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80(2):195–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicari F A Zukowski M Endoscopic assisted craniofacial surgery In Marchac D, ed. Craniofacial Surgery 6. Proceedings of the Sixth Inter- national Congress of the International Society of Craniofacial Surgery. Monduzzi Editore: Bologna, Italy; 199577–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez D F, Barone C M. Endoscopic craniectomy for early surgical correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1998;88(1):77–81. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barone C M Jimenez D F Endoscopic craniectomy for early correction of craniosynostosis Plast Reconstr Surg 199910471965–1973., discussion 1974–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendel P M, Nadell J M. Projection geometry and stress-reduction techniques in craniofacial surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(2):217–227. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]