Abstract

The complex three-dimensional anatomy of the craniofacial skeleton creates a formidable challenge for surgical reconstruction. Advances in computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing technology have created increasing applications for virtual surgical planning in craniofacial surgery, such as preoperative planning, fabrication of cutting guides, and stereolithographic models and fabrication of custom implants. In this review, the authors describe current and evolving uses of virtual surgical planning in craniofacial surgery.

Keywords: virtual surgical planning, craniofacial surgery, craniosynostosis, cranial vault remodeling, distraction osteogenesis

The complex three-dimensional (3D) anatomy of the craniofacial skeleton increases the complexity of reconstructing this region and creates a challenge when attempting to achieve excellent aesthetic outcomes. Traditionally, reconstructive surgery for conditions such as craniosynostosis and complex facial malformations has relied on the surgeon's subjective assessment of form and aesthetics preoperatively and intraoperatively, with intraoperative decision making based on such factors as the location of bone cuts and the shape of bone segments for craniofacial reconstruction. Although good outcomes can and are often achieved, the highly subjective nature of this process results in variable surgeon-specific outcomes and can also lead to prolonged surgical time.

The advent of virtual surgical planning (VSP) through computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) techniques has offered an alternative workflow1 2 3 for more precise preoperative planning and a decreased necessity for intraoperative trial and error. Applications include preoperative planning through virtual surgery,4 5 fabrication of cutting guides and bone models using stereolithography techniques,6 7 and surgical navigation systems to aid in the placement of implants and to guide bone cuts.8 9

Although CAD-CAM technology has been present for decades, recent developments have made it more relevant for use in craniofacial surgery. Improvement in resolution and quality of images as well as decreased slice thickness obtained from computed tomography (CT) scans allow generation of more accurate 3D models for surgical planning and manipulation.6 Advanced surgical simulation tools allow manipulation of the 3D craniofacial model with 6 degrees of freedom,10 11 12 therefore allowing visualization of simulated osteotomies from different angles. Advances in rapid prototyping technology allow fabrication of more accurate 3D models with detailed internal contours through stereolithography techniques as well as fabrication of cutting guides for osteotomies after preoperative virtual surgery.13 14 However, there are increased costs related to VSP in some procedures that are not offset by the savings in valuable surgical time.

In this article, we review current and evolving applications of virtual surgical planning in craniofacial surgery.

Applications in Craniosynostosis Surgery

Cranial vault remodeling aims to correct abnormal cranial morphology as much as possible toward age-matched norms. Understandably, there is significant subjectivity in what is ideal or normal. The concept of CAD-CAM technology for craniosynostosis surgery was first proposed in 199615 subsequently, the technology was implemented in a patient with metopic synostosis and another with unicoronal synostosis by Mommaerts et al in 2001.16 The 3D CAD-CAM planning was converted to 2D templates that were used to plan osteotomies. The process was time-consuming due to the need to transfer a 3D plan to 2D templates. Burge and colleagues subsequently described in 201117 the use of CAD-CAM technology for fabricating age-matched templates for shaping of the fronto-orbital bandeau. However, these templates were limited to remodeling of the fronto-orbital bandeau only.

Nikoo described a mathematically averaged skull based on CT scan data of 103 infants aged 8 to 12 months.18 Based on normative data generated from measurements of radiographs from children,17 19 age-appropriate calvarial models were generated with the aid of a company specializing in virtual surgical planning, Medical Modeling Inc. (Golden, CO).

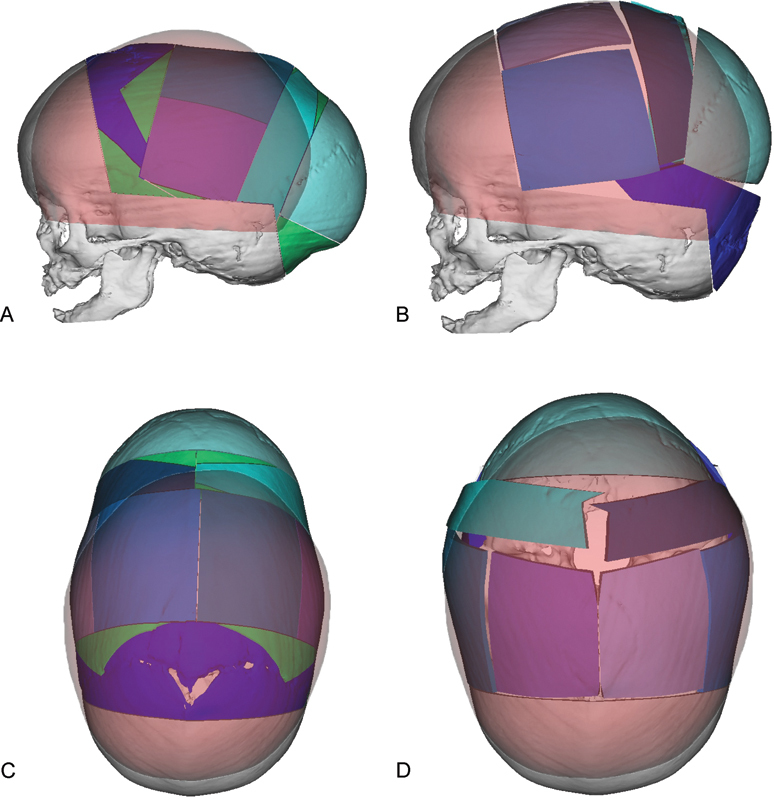

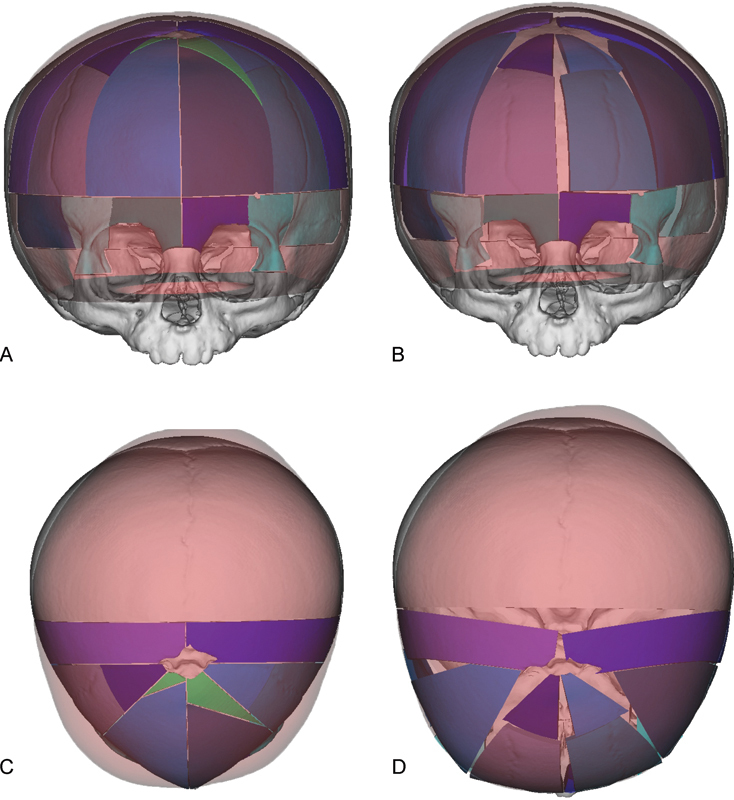

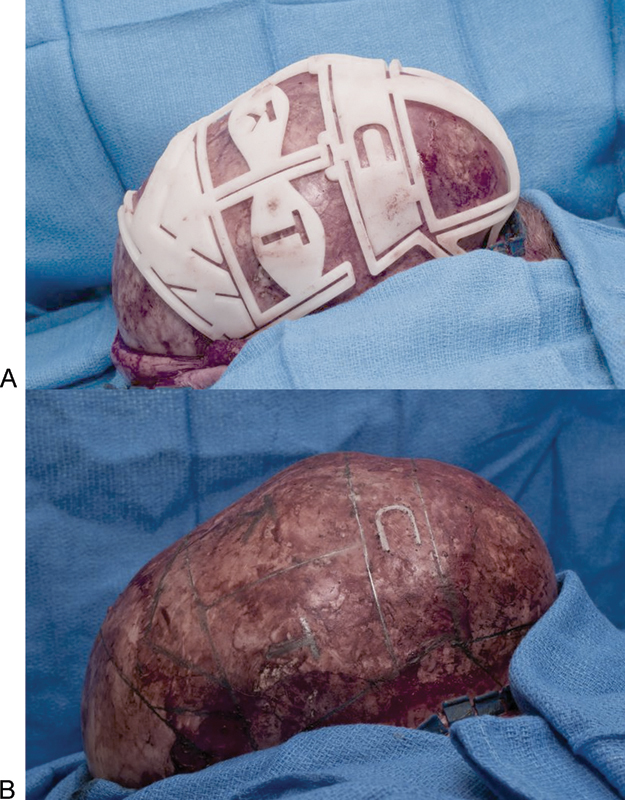

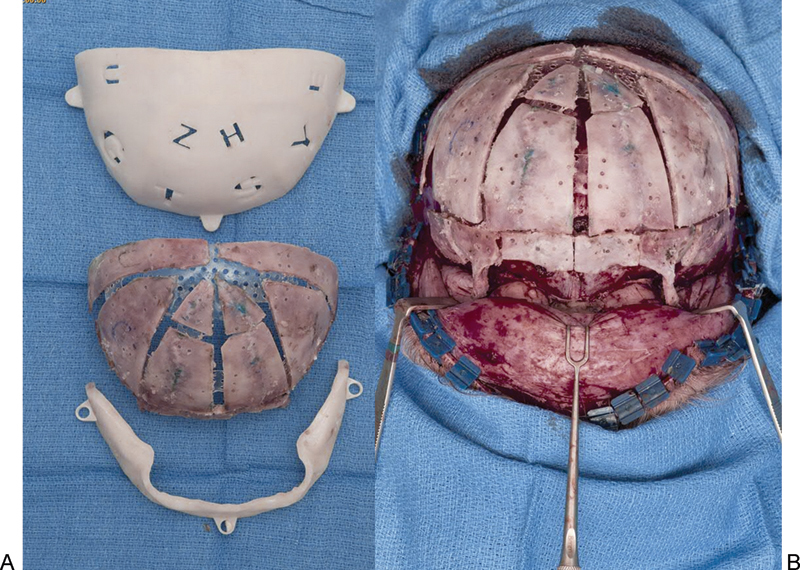

These normative calvarial models are used as an aid during virtual surgery (Figs. 1 and 2). Data obtained from CT images of the patient are used to make the first model, whereas an age-appropriate normative model is used as the second model. The two models are overlapped, and virtual osteotomies are performed to reshape the patient's skull to best fit its normative model. With the aid of virtual surgery, the planned surgical osteotomies are uploaded into the computer to allow fabrication of templates for use in the actual surgery. The cutting guides (Fig. 3) show where osteotomies should be made on the calvarium; the positioning guides (Fig. 4) help to guide placement of individual bone segments to best approximate an age-appropriate normal calvarial shape.

Fig. 1.

Virtual surgical planning is used to simulate osteotomies and repositioning of bone segments during cranial vault remodeling for correction of sagittal synostosis. “Normal” age matched skull is colored red. Virtual osteotomized segments are shown in blue, green, and purple. (A) Preoperative lateral view showing planned osteotomies based on overlapping a “normal” age matched skull onto the patient's skull. (B) Projected postoperative lateral view following re-shaping of the cranial vault to match the “normal” skull. (C) Preoperative view from the top of the skull showing planned osteotomies. (D) View following re-shaping of the cranial vault to match as age matched “normal”.

Fig. 2.

Virtual surgical planning is used to simulate osteotomies and repositioning of bone segments during cranial vault remodeling for correction of metopic synostosis. “Normal” age matched skull is colored red. Virtual osteotomized segments are shown in blue, green, and purple. (A) Preoperative AP view showing planned osteotomies. (B) Projected postoperative AP view following re-shaping of the cranial vault. (C) Preoperative overhead view showing planned osteotomies. (D) Projected postoperative overhead view following re-shaping of the cranial vault shows correction of trigonocephaly.

Fig. 3.

Cutting template allows exact placement of osteotomies and labeling of individual bone segments in a patient with sagittal synostosis. (A) Placement of the template on the calvarium after elevation of the scalp flaps. (B) Marking of planned osteotomies on the calvarium.

Fig. 4.

Positioning guides used for placement of individual bone segments to best achieve an age-matched normal calvarial morphology in a patient with metopic synostosis. (A) In this case, bone segments are placed on the internal surface of the template and secured with resorbable plates internally. This can be performed with the bone segments placed on the outside of a positioning guide and plating on the outside. This depends on the preference of the surgeon and the planning of each particular surgery. (B) The reconstructed calvarium is transferred to the patient and further secured with resorbable plates on the external aspect.

In cranial vault distraction, virtual surgical planning allows preoperative determination of the distance and vector of distraction, as well as the best position for the osteotomies. Additionally, the bone can be analyzed preoperatively to determine where solid bone exists for optimal placement of the distractors. Potential use in some situations is based on the determination of the thickness of the calvarial bone, which can aid in determining the length of the screws to be used.

Virtual surgical planning has been used successfully by our group7 and others20 21 to aid reconstruction in infants with craniosynostosis. This technique allows reproducible objective results that improve outcomes. The surgeon begins the surgery knowing the final outcome. Other benefits include a better understanding of the pathology and surgical steps by parents and families through visual 3D images obtained through the VSP process. While planning the surgery, the surgeon is able to visualize exactly where the planned cuts will be made in relation to critical structures around the brain, therefore avoiding potential complications. In the planning process, the bioengineer shows axial and coronal cuts that correspond to the 3D model where these cuts will end up in relation to the structures around the brain and skull base. The use of VSP requires a CT scan within 1 or 2 months of the surgery to perform proper planning. The timing is dependent on the age of the patient at the time of surgery. After the period of rapid cranial growth, an older CT scan may be used. The craniofacial surgeon must balance the advantage of increased precision obtained from VSP, with the disadvantage of possible increased cost and exposure to radiation when deciding whether to use VSP in their craniosynostosis practice. The use of VSP is illustrated by two case examples below.

Case 1: Metopic Synostosis

A 2-month-old boy presented with abnormal head shape and was diagnosed with metopic synostosis (Fig. 5). After virtual surgical planning, he underwent cranial vault remodeling at 12 months of age. Approximately 1 week after surgery, he bumped his head and developed a subdural fluid collection that required surgical evacuation. He has had good results 9 months after surgery. To achieve optimal shape, the supraorbital bandeau and frontal bones were segmented into many pieces. This is not optimal and should be avoided whenever possible to avoid desorption. Also, plating on the inside versus outside is dependent on the surgeon's preference and on the location of the plates. The planning allows the surgeon to produce positioning guides that place the bone segments on the inside with plating on the inside (as seen in this case), or positioning guides that allow placement of the bone segments on the outside with plates on the outside.

Fig. 5.

Virtual surgical planning for cranial vault remodeling in a patient with metopic synostosis. (A,B) Preoperative frontal and lateral view of a child with metopic synostosis. (C,D) Oblique views of cutting guides based on VSP of this patients surgery. (E) Cutting guide in place after elevation of the anterior scalp flap. (F) Marking of planned osteotomies on the calvarium. (G) Positioning guide used to reshape bone segments on the back table. (H) Reconstructed anterior cranial vault and supraorbital bar in place. (I,J) Postoperative frontal and lateral view.

Case 2: Coronal Synostosis

A 3-month-old girl with Crouzon syndrome presented with bicoronal synostosis and hydrocephalus (Fig. 6). She underwent posterior cranial vault distraction at 14 months of age. Postoperative photos were obtained 3 months after completion of distraction; they show a good surgical result.

Fig. 6.

Virtual surgical planning for posterior cranial vault distraction in a syndromic patient with bilateral coronal synostosis. (A,B) Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral view. (C) Overlap of patient's skull with normal age-matched skull (red). (D) Distracted segment (in blue) positioned where it needs to be to achieve normal morphology. (E) Distractors in place in positions that allow for distracting in the planned vector. (F) Cutting guide placed over a three-dimensional model of the patient's abnormal skull. (G) Distractors in placed after osteotomy is performed. (H,I,J) Postoperative views of the patient after 30 mm of distraction performed and prior to removal of distractors.

Applications in Maxillofacial Reconstruction

Virtual surgical planning has proven to be very useful in complex maxillofacial reconstruction. In the area of mandibular reconstruction, VSP has been used in the shaping of free fibular flaps.22 23 With data obtained from high-resolution CT scans of the maxillofacial skeleton and lower extremity, stereolithographic models can be fabricated, whereas virtual surgery allows fabrication of mandible and fibular cutting guides and a plate-bending template for shaping the fibula to best approximate the desired shape of the reconstructed mandible. With VSP, intraoperative time is decreased as bending and shaping of the plate and fibula can now be done with precision to match the dimensions of the defect,24 and not freehand as is the traditional technique. This is extremely valuable in decreasing ischemia time; the accuracy of the fibular osteotomies allows better shape and optimizes the position of the bones for eventual dental rehabilitation.

The use of VSP in mandibular reconstruction consists of a planning phase, modeling phase, and surgical phase.25 High-resolution CT scans of the craniofacial skeleton and lower extremities are obtained. These images are forwarded to a company specializing in VSP. After an online meeting to discuss the case, a virtual resection of the mandible is performed. The 3D image of the fibula is superimposed on the defect and virtual osteotomies are performed. In the modeling phase, a stereolithographic model is fabricated, as well as cutting guides for the mandible and fibula. Finally, in the surgical phase, the mandible cutting guides are used to guide resection of the lesion. A temporary external fixator may be placed to ensure that the remaining segments are kept in proper position. Otherwise, more commonly, a reconstruction plate and drilling of holes at appropriate locations on the remaining mandible are placed prior to performing the osteotomies. The reconstruction plate is removed and the cutting guides are placed in preparation for the osteotomies. The fibula is shaped using the fibular cutting guide, prior to or after division of the pedicle. The shaped fibula is used to reconstruct the mandible.

Virtual surgical planning with stereotactic navigation has been used for midface reconstruction with free fibular flaps.26 Physical models are created using rapid prototyping techniques. Titanium plates are then bent to match the contours of the fibular flap and facial skeleton. In addition, custom cutting guides are fabricated for the fibular osteotomies. Navigation is performed with fiducial markers on the patient's forehead, subsequently replaced by a navigation array fixed to the patient's calvaria at the time of surgery. Virtual surgical planning has also been used for complex reconstruction of the midface and mandible with two separate free fibular flaps.27 In extensive defects, where the native anatomy of the face is distorted by trauma or irradiation, the amount of bone required for reconstruction can be underestimated. Virtual surgical planning obviates this problem by allowing the visualization of the preinjury 3D anatomy to aid planning of osteotomies preoperatively, saving valuable surgical time.

Another application of VSP allows immediate prosthodontic rehabilitation in mandibular reconstruction.28 29 Dental implants are placed in the fibula in the first stage to allow for osseointegration, followed by free fibular transfer in the second stage, allowing immediate implant-supported prosthetic rehabilitation with dentures.

In addition to midface reconstruction using free fibular flaps, a group used VSP's cutting guides to aid in their completion of osteotomies in vascularized iliac crest bone grafts for zygoma reconstruction.30 The same group used VSP for preoperative planning and fabrication of cutting guides for vascularized iliac crest bone grafts in mandibular reconstruction, and found that surgical time was decreased and the iliac crest donor site defect was downsized when VSP was used.31

Other Applications of Virtual Surgical Planning

Virtual surgical planning has been used in planning mandibular distraction osteogenesis in a neonate32 with Pierre Robin syndrome. Three-dimensional models are fabricated based on CT scan data of the craniofacial skeleton and distractors. Virtual surgery is performed to ensure that the planned osteotomies would allow achievement of the planned distraction vector. Cutting guides for the mandible are then fabricated to allow accurate cuts intraoperatively. Virtual surgical planning also allows preplanning of screw position and lengths to ensure bicortical screw placement, away from the inferior alveolar nerve. The cutting guides allow sliding of the actual distractors over K wires to improve efficiency and accuracy of placement of the distractors.

Custom alloplastic total joint replacement implants of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) have been used for treatment of TMJ ankylosis33 in a single-stage surgery. Similar to the workflow for other applications in VSP, fine-cut CT scans of the TMJ and maxillomandibular complex are obtained, followed by the creation of 3D models by a company experienced in VSP. Through an interactive online meeting, virtual surgery is performed, consisting of the resection of the ankylosed segment. The joint replacement is then designed, first with planning of the fossa component with a custom-made flange to fit the patient's zygomatic arch, followed by design of the mandibular ramus component. Accurate visualization of the 3D anatomy of the mandible ensures that the prosthesis and fixation avoid the inferior alveolar nerve and tooth roots. Finally, a virtual 3D prosthesis is designed. Screw holes can be placed away from vital structures such as the inferior alveolar nerve and maxillary artery and over the best bone thickness for fixation. In addition, measurement of screw depth is obtained to ensure that screw placement is bicortical for all holes. Bone-cutting guides are also fabricated to fit the posterior border of the mandible and/ or glenoid fossa and aid the resection phase of the surgery.

Virtual surgical planning in surgery for TMJ ankylosis allows performance of the surgery in a single stage, compared with traditional multiple-stage surgeries that involve resection of the ankylosis, followed by reconstruction. The accuracy of implant fabrication and placement is increased, with decreased micro-movement under loading compared with standard implants, while morbidity related to multiple surgeries is avoided.

Virtual surgical planning has also been used for single-stage resection and reconstruction of the TMJ using stock prostheses from Biomet.34 In these cases, cutting guides aid in the performance of osteotomies intraoperatively, while stereolithographic models allow the selection of appropriately sized prosthesis components prior to surgery to ensure the best fit. In these situations, where the complex bony anatomy of the TMJ prevents easy selection of prosthesis size and placement, VSP has a role in preoperative visualization and planning to decrease surgical time.

Virtual surgical planning has a clear role in facial transplantation where bone is a necessary component in the completion of the reconstruction.35 36 If a Lefort III segment is planned, cutting guides and templates are fabricated for the recipient and for the donor at the appropriate times. Additionally, VSP can be used in surgical navigation. The use of VSP for this indication ensures a more accurate outcome while minimizing ischemia time.

Conclusion

The use of VSP can lead to increased accuracy in reconstructing the craniofacial skeleton. Its applications and practicality continue to be explored as new technology becomes available and as experience with the current technology increases.

References

- 1.Bly R A, Chang S H, Cudejkova M, Liu J J, Moe K S. Computer-guided orbital reconstruction to improve outcomes. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15(2):113–120. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley B D, Thayer W P, Honeybrook A, McKenna S, Press S. Mandibular reconstruction using computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing: an analysis of surgical results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(2):e111–e119. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hierl T, Arnold S, Kruber D, Schulze F P, Hümpfner-Hierl H. CAD-CAM-assisted esthetic facial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(1):e15–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikkhah D, Ponniah A, Ruff C, Dunaway D. Planning surgical reconstruction in Treacher-Collins syndrome using virtual simulation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):790e–805e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a48d33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tepper O M, Sorice S, Hershman G N, Saadeh P, Levine J P, Hirsch D. Use of virtual 3-dimensional surgery in post-traumatic craniomaxillofacial reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(3):733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao L, Patel P K, Cohen M. Application of virtual surgical planning with computer assisted design and manufacturing technology to cranio-maxillofacial surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39(4):309–316. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.4.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mardini S, Alsubaie S, Cayci C, Chim H, Wetjen N. Three-dimensional preoperative virtual planning and template use for surgical correction of craniosynostosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(3):336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma S N, Schow S R, Stone B H, Triplett R G. Applications of surgical navigational systems for craniofacial bone-anchored implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010;25(3):582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowinski D, Messo E, Hedlund A, Hirsch J M. Computer-navigated contouring of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia involving the orbit. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(2):469–472. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182074312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cynthia D B, Steven S, Anil M. et al. A survey of interactive mesh-cutting techniques and a new method for implementing generalized interactive mesh cutting using virtual tools. J Visual Comput Animat. 2002;13:21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachow S, Gladilina E, Saderb R. et al. Draw and cut: intuitive 3D osteotomy planning on polygonal bone models. Int Congr Ser. 2003;1256:362–369. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westermark A, Zachow S, Eppley B L. Three-dimensional osteotomy planning in maxillofacial surgery including soft tissue prediction. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(1):100–104. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200501000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGurk M, Amis A A, Potamianos P, Goodger N M. Rapid prototyping techniques for anatomical modelling in medicine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79(3):169–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joffe J M, McDermott P J, Linney A D, Mosse C A, Harris M. Computer-generated titanium cranioplasty: report of a new technique for repairing skull defects. Br J Neurosurg. 1992;6(4):343–350. doi: 10.3109/02688699209023793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vander Sloten J, Degryse K, Gobin R, Van der Perre G, Mommaerts M Y. Interactive simulation of cranial surgery in a computer aided design environment. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24(2):122–129. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(96)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mommaerts M Y, Jans G, Vander Sloten J, Staels P F, Van der Perre G, Gobin R. On the assets of CAD planning for craniosynostosis surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12(6):547–554. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burge J, Saber N R, Looi T. et al. Application of CAD/CAM prefabricated age-matched templates in cranio-orbital remodeling in craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(5):1810–1813. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31822e8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saber N R, Phillips J, Looi T. et al. Generation of normative pediatric skull models for use in cranial vault remodeling procedures. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28(3):405–410. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1630-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira I MR, Filho A AB, Alvares B R, Palomari E T, Nanni L. Radiological determination of cranial size and index by measurement of skull diameters in a population of children in Brazil. Radiol Bras. 2008;41:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seruya M, Borsuk D E, Khalifian S, Carson B S, Dalesio N M, Dorafshar A H. Computer-aided design and manufacturing in craniosynostosis surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(4):1100–1105. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31828b7021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khechoyan D Y, Saber N R, Burge J. et al. Surgical outcomes in craniosynostosis reconstruction: the use of prefabricated templates in cranial vault remodelling. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moro A, Cannas R, Boniello R, Gasparini G, Pelo S. Techniques on modeling the vascularized free fibula flap in mandibular reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(5):1571–1573. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181b0db5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antony A K, Chen W F, Kolokythas A, Weimer K A, Cohen M N. Use of virtual surgery and stereolithography-guided osteotomy for mandibular reconstruction with the free fibula. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(5):1080–1084. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roser S M, Ramachandra S, Blair H. et al. The accuracy of virtual surgical planning in free fibula mandibular reconstruction: comparison of planned and final results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2824–2832. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.06.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch D L, Garfein E S, Christensen A M, Weimer K A, Saddeh P B, Levine J P. Use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing to produce orthognathically ideal surgical outcomes: a paradigm shift in head and neck reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(10):2115–2122. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanasono M M, Jacob R F, Bidaut L, Robb G L, Skoracki R J. Midfacial reconstruction using virtual planning, rapid prototype modeling, and stereotactic navigation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):2002–2006. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f447e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saad A, Winters R, Wise M W, Dupin C L, St Hilaire H. Virtual surgical planning in complex composite maxillofacial reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(3):626–633. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829ad299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohner D, Jaquiéry C, Kunz C, Bucher P, Maas H, Hammer B. Maxillofacial reconstruction with prefabricated osseous free flaps: a 3-year experience with 24 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(3):748–757. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000069709.89719.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schepers R H, Raghoebar G M, Vissink A. et al. Fully 3-dimensional digitally planned reconstruction of a mandible with a free vascularized fibula and immediate placement of an implant-supported prosthetic construction. Head Neck. 2013;35(4):E109–E114. doi: 10.1002/hed.21922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modabber A, Gerressen M, Ayoub N. et al. Computer-assisted zygoma reconstruction with vascularized iliac crest bone graft. Int J Med Robot. 2013;9(4):497–502. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayoub N, Ghassemi A, Rana M. et al. Evaluation of computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction with vascularized iliac crest bone graft compared to conventional surgery: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Trials. 2014;15:114. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doscher M E, Garfein E S, Bent J, Tepper O M. Neonatal mandibular distraction osteogenesis: converting virtual surgical planning into an operative reality. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(2):381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haq J, Patel N, Weimer K, Matthews N S. Single stage treatment of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint using patient-specific total joint replacement and virtual surgical planning. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(4):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandran R, Keeler G D, Christensen A M, Weimer K A, Caloss R. Application of virtual surgical planning for total joint reconstruction with a stock alloplast system. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(1):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown E N, Dorafshar A H, Bojovic B. et al. Total face, double jaw, and tongue transplant simulation: a cadaveric study using computer-assisted techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(4):815–823. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f2c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chim H, Amer H, Mardini S, Moran S L. Vascularized composite allotransplantation in the realm of regenerative plastic surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]