Abstract

Objective

Determine if employment-based reinforcement can increase methadone treatment engagement and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users.

Method

This study was conducted from 2008–2012 in a therapeutic workplace in Baltimore, MD. After a 4-week induction, participants (N=98) could work and earn pay for 26 weeks and were randomly assigned to Work Reinforcement, Methadone & Work Reinforcement, and Abstinence, Methadone & Work Reinforcement conditions. Work Reinforcement participants had to work to earn pay. Methadone & Work Reinforcement, and Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants had to enroll in methadone treatment to work and maximize pay. Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples to maximize pay.

Results

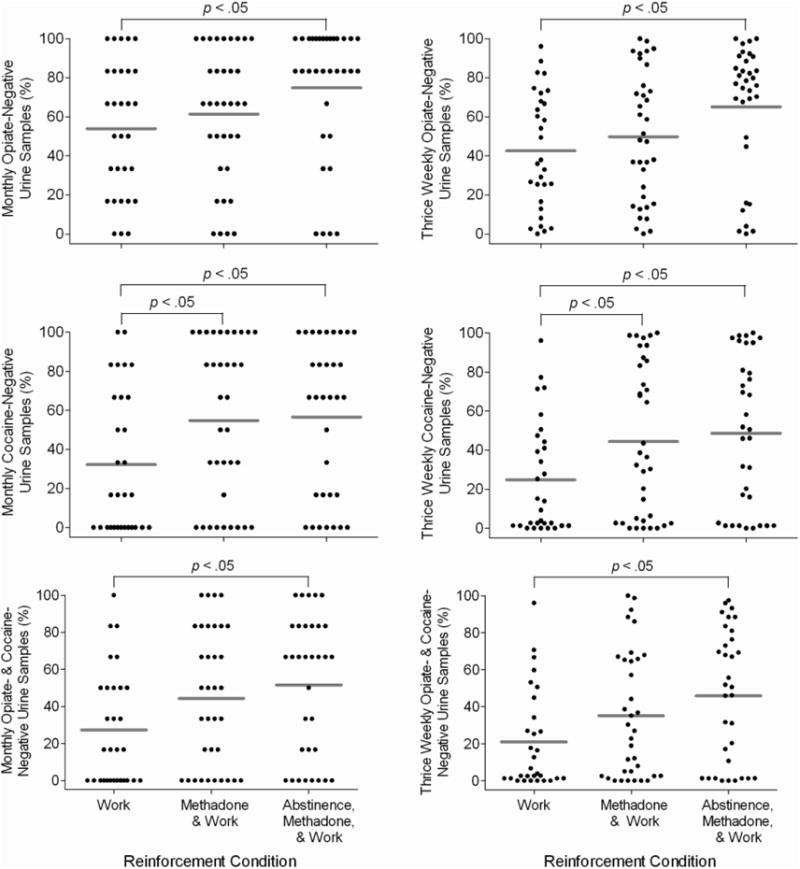

Most participants (92%) enrolled in methadone treatment during induction. Drug abstinence increased as a graded function of the addition of the methadone and abstinence contingencies. Abstinence, Methadone & Work Reinforcement participants provided significantly more urine samples negative for opiates (75% versus 54%) and cocaine (57% versus 32%) than Work Reinforcement participants. Methadone & Work Reinforcement participants provided significantly more cocaine-negative samples than Work Reinforcement participants (55% versus 32%).

Conclusion

The therapeutic workplace can promote drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users.

Keywords: methadone, contingency management, financial incentives, cocaine, opiate, employment, injection drug use, out-of-treatment injection drug user

Injection drug use remains a common mode of HIV transmission (Mathers, Degenhardt, and Phillips, 2008; Vlahov, Robertson, and Strathdee, 2010). The prevalence of HIV among injection drug users is due, in part, to the sharing of unsterile injection equipment (Abdala, Stephens, Griffith, and Heimer, 1999; Degenhardt et al., 2010). Because of this, a central approach to HIV prevention has been the reduction of injection drug use.

Methadone maintenance can reduced opioid use (Ball, Lange, Myers, and Friedman, 1988; Hubbard, Craddock, Flynn, Anderson, and Etheridge, 1997; Sullivan, Metzger, Fudala, and Fiellin, 2005), lower rates of opioid injection and injection-related HIV risk behaviors (Booth, Crowley, and Zhang, 1996; Caplehorn, and Ross, 1995; Farrell, Gowing, Marsden, Ling, and Ali, 2005; Kwiatkowski and Booth, 2001), and lower rates of HIV incidence and prevalence (Barthwell, Senay, Marks, and White, 1989; Friedman, Jose, Deren, Des Jarlais, and Neaigus, 1995; Metzger et al., 1993). Despite methadone's efficacy in decreasing opioid use and HIV transmission, methadone remains a treatment option that most opioid-addicts do not use (Al-Tayyib and Koester, 2011; Kleber, 2008; Peterson et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2008; Zaller, Bazazi, Velazquez, and Rich, 2009).

Strategies to increase treatment entry among injection drug users have met with some success. These include the removal of intake delays (Dennis, Ingram, Burks, and Rachal, 1994; Schwartz et al., 2006), providing coupons for free treatment (Booth, Corsi, and Mikulick, 2003; Bux, Iguchi, Lidz, Baxter, and Platt, 1993; Sorensen, Constantini, Wall, and Gibson, 1993), case management (Mejta, Bokos, Mickenberg, Maslar, and Senay, 1997; Robles et al., 2004; Strathdee et al., 2006), addressing the lack of available treatment slots (Peterson et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2006), combining motivational interviewing with incentives (Kidorf et al., 2009; Kidorf, King, Gandotra, Kolodner, & Brooner, 2012), and eliminating treatment fees (Booth, Kwiatkoswki, Iguchi, Pinto, and John, 1998). Although these methods have increased treatment enrollment, about half or more of injection drug users exposed to these interventions remain outside of treatment. Furthermore, many individuals who enter methadone treatment continue to use opiates and cocaine (Grella, Anglin, Wugalter, 1997; Hartel et al., 1995; Magura, Kang, Nwakeze, & Demsky, 1998). Additional measures may be necessary to engage out-of-treatment injection drug users and to promote abstinence in individuals who do enroll in treatment.

The therapeutic workplace, an intervention that targets drug addiction and chronic unemployment, may be a viable approach to promote enrollment in methadone treatment and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users. The therapeutic workplace integrates voucher-based reinforcement contingencies that have been considerably effective in the treatment of drug addiction (Higgins et al., 1991; Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger and Higgins, 2006) into an employment program (Silverman, 2004). In this program, unemployed, drug-addicted adults are hired and paid as employees in a model workplace. To access the workplace and maintain maximum pay, participants are required to engage in behavior change, such as providing drug-negative urine samples and adhering to medication treatment. Because many unemployed adults with histories of drug addiction lack skills to obtain employment, therapeutic workplace participants initially receive skills training to prepare them for employment. Participants who become skilled and abstinent then can perform real jobs. Because the therapeutic workplace could simultaneously address unemployment and drug addiction, it could be an ideal intervention for out-of-treatment injection heroin users, many of whom are unemployed (Kidorf et al., 2005; Kwiatkowski et al., 2000; Strathdee et al., 2006). In a number of clinical trials, the therapeutic workplace has initiated and maintained abstinence from opiates, cocaine, and alcohol and has promoted adherence to oral and extended-release naltrexone treatment (Everly et al., 2011; DeFulio et al., 2012; DeFulio, Donlin, Wong, and Silverman, 2009; Donlin, Knealing, Needham, Wong, Silverman, 2008; Dunn et al., 2013; Silverman et al., 2007; Silverman, DeFulio and Sigurdsson, 2012; Silverman, Svikis, Robles, Stitzer, and Bigelow, 2001; Silverman, Svikis, Wong, Hampton, Stitzer, and Bigelow, 2002). The present randomized controlled trial was conducted to examine whether the therapeutic workplace could promote enrollment in methadone treatment and abstinence from opiates and cocaine in out-of-treatment injection drug users.

Methods

Setting and participant selection

The present study was conducted at the therapeutic workplace at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (Baltimore, MD). The workplace contained a urinalysis laboratory and three workrooms equipped with computers (see Silverman et al., 2007 for details of the therapeutic workplace). The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and is a registered clinical trial (NCT01416584).

Recruitment began in December 2008 and the study ended in December 2012. During this time, waiting lists for methadone treatment in Baltimore were common. One study indicated that the waiting list for a methadone treatment slot was approximately 3 months (Peterson et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2007). However, interim methadone treatment was available if a methadone maintenance treatment slot was not open.

Participants were recruited through agencies that served the target population, street outreach, and a respondent-driven sampling referral system in which study participants were paid for successfully referring others to the study. Interested individuals completed a brief screening interview that gauged study eligibility. Applicants were invited to participate in a full screening interview if they were 18 years or older, lived in Baltimore, were unemployed, were not receiving substance abuse treatment, and reported injecting heroin.

Full screening interview

Participants completed a full screening interview to determine study eligibility. The screening included urine samples collected under observation and tested for opiates, cocaine, methadone, buprenorphine, benzodiazepines, and amphetamines using an Abbott AxSYM® (Abbott Park, IL, USA); the Addiction Severity Index–Lite (ASI–Lite; McLellan et al., 1985) for evaluating drug use, educational, employment, family, medical, and legal histories; the heroin and cocaine sections of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview–2nd edition (CIDI2; Compton, Cottler, Dorsey, Spitznagel, and Mager, 1996), to assess drug dependence; the Wide Range Achievement Test–4th edition (WRAT4; Wilkinson, 1993) to assess math, reading, and spelling skills; the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB; Navaline et al., 1994) for evaluating HIV risk behaviors; the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to measure global self-esteem and personal worthlessness (Rosenberg, 1989); and a questionnaire that asked participants to rate their interest in methadone (adapted from Booth et al., 2003). Additional exploratory measures were collected but are not reported here. Participants were paid $30 in vouchers for completing the full screening interview.

Individuals were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, reported injection drug use in the past 30 days, met the DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), reported using heroin at least 21 out of the past 30 days, provided an opiate-positive urine sample, showed visible signs of injection drug use (i.e., track marks), reported not receiving substance abuse treatment in the past 30 days, lived in Baltimore, and were unemployed. Participants were excluded if they had current severe psychiatric disorders or chronic medical conditions that would interfere with their ability to participate in the workplace, reported current suicidal or homicidal ideation, had physical limitations that would prevent them from using a keyboard, had medical insurance coverage (as this would disqualify them from receiving interim methadone treatment), were pregnant or breastfeeding, or were currently considered a prisoner. Eligible participants were invited to participate in a 4-week induction.

Induction

During induction, participants were invited to attend the therapeutic workplace. Participants were asked if they would like to schedule an intake appointment for methadone treatment. If a participant expressed interest in an appointment, study staff scheduled the appointment and provided the participant with an appointment card. Additionally, every Monday participants were asked if they were in methadone treatment. If participants indicated that they were in treatment, their methadone program was contacted to confirm enrollment. If participants indicated that they were not in treatment, participants were asked if they would like to schedule an appointment.

The induction period provided exposure to the workplace prior to imposing any contingencies. Participants could attend the workplace for four hours every weekday for four weeks and could earn $8 per hour in base pay plus about $2 per hour for their performance on training programs. Participants were paid in vouchers that were exchangeable for goods and services. Urine samples were collected and tested for opiates and cocaine prior to work on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Participants who attended the workplace for at least five minutes on two out of five workdays in the last week of induction were randomly assigned to one of three conditions and were invited to attend the workplace for an additional 26 weeks. The maximum possible amount of vouchers participants could earn for 30 weeks of participation was $6,000.

Experimental design and conditions

Stratification and random assignment

Participants were randomly assigned, via a computer program operated by a study coordinator who did not have direct contact with participants to a Work Reinforcement, Methadone & Work Reinforcement, or Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition using a stratification procedure that evenly distributed participants across conditions based on three stratification variables: (1) enrolled in methadone treatment during induction, (2) self-reported interest in methadone treatment, and (3) provided more than 50% cocaine-negative urine samples during induction. The rules according to which participants were allowed access to the workplace and could maintain their base pay rate during the 26-week intervention evaluation period varied based on condition assignment.

Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition

For Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants, access to the workplace and the opportunity to earn vouchers was contingent on their methadone treatment status and urinalysis results. A methadone contingency was implemented one week after randomization. Every Monday, participants were asked if they were in methadone treatment. If participants indicated that they were in treatment, their methadone program was contacted to confirm enrollment. If a participant was not enrolled, the participant was not allowed to work the next day or any day thereafter until methadone treatment was initiated or resumed. Additionally, the participant's base pay was reset from $8 to $1 per hour. After the reset, the participant's base pay could increase by $1 per hour to the maximum of $8 per hour for every day that the participant was enrolled in methadone treatment and attended the workplace for at least five minutes. Once an Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participant was enrolled in methadone treatment for three consecutive weeks, opiate and cocaine abstinence requirements were introduced sequentially. Specifically, an opiate abstinence contingency was implemented in which urinary morphine concentrations had to be less than 300 ng/ml or at least 20% lower per day since the last sample that was submitted. Failure to meet the abstinence requirement or to provide a urine sample on mandatory urine days (typically Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays) resulted in a base pay reset from $8 to $1 per hour. After the reset, the participant's base pay increased by $1 per hour to the maximum of $8 per hour for every day that the participant provided an opiate-negative sample and worked for 5 minutes. After three consecutive weeks of meeting the opiate abstinence requirement, the abstinence contingency was expanded to cocaine (i.e., urinary benzoylecgonine and morphine concentrations had to be less than 300 ng/ml or at least 20% lower per day since the last sample submitted).

Methadone & Work Reinforcement condition

For Methadone & Work Reinforcement participants, access to the workplace and the opportunity to earn vouchers was contingent on their methadone treatment status. Procedures for verifying methadone enrollment and consequences for not being enrolled were the same as those for the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition.

Work Reinforcement condition

Work Reinforcement participants could work and earn vouchers independent of their methadone treatment status and independent of whether their urine samples tested positive for opiates or cocaine.

Therapeutic workplace training programs

Participants worked on computer-based typing and keypad programs and the Individual Prescription for Achieving State Standards (iPASS) program (“iLearn,” 2013) while attending the therapeutic workplace. The typing and keypad programs taught participants to type characters using a QWERTY keyboard and numeric keypad (see Koffarnus et al., 2013 for details of the typing and keypad programs). The iPASS program provided individual math instruction based on specific skill deficits of the participant.

Major and monthly assessments

Major assessments were conducted immediately prior to random assignment and 6 months after the end of the 26-week intervention evaluation period (6-month follow-up). Monthly assessments were conducted every 30 days throughout the 26-week intervention evaluation period. Independent of attendance at the workplace, participants were contacted and offered $30 in vouchers for the completion of an assessment, except for the follow-up assessment for which they were offered $50. These assessments included the collection of urine samples, as well as the administration of some of the questionnaires collected at intake by a staff member who was blind to participants' conditions.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the percentage of participants enrolled in methadone treatment (based on participant self-report and confirmations from the methadone clinics) and the percentage of urine samples negative for opiates and cocaine. Urine samples were negative for opiates and cocaine if the concentration of the metabolite, morphine or benzoylecgonine, respectively, was ≤ 300 ng/ml. Additional analyses included self-reported HIV risk behaviors, workplace attendance, voucher earnings, and total hours worked.

Data analyses

Participant characteristics at intake were analyzed using Fisher's exact or Chi-square tests for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variances for continuous variables. Methadone enrollment and HIV risk behavior analyses were from the major and monthly assessments. Analyses of urine samples were based on the major and monthly assessments, as well as the thrice-weekly urine samples. Dichotomous outcome measures assessed at single time-points (e.g., at randomization) were analyzed with logistic regression. Dichotomous outcome measures assessed repeatedly over time were analyzed using general estimating equations (GEE). Results of these analyses are reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were performed in which the three stratification variables were and were not used as covariates. Unless otherwise specified, missing urine samples were coded as positive for opiates and cocaine (missing-positive). An alternative method of handling missing urine samples was analyzed in which missing samples were not replaced (missing-missing). All analyses were intent-to-treat, considered significant if p ≤ .05, and conducted using Stata software version 11.

Results

Participant characteristics and flow through the study

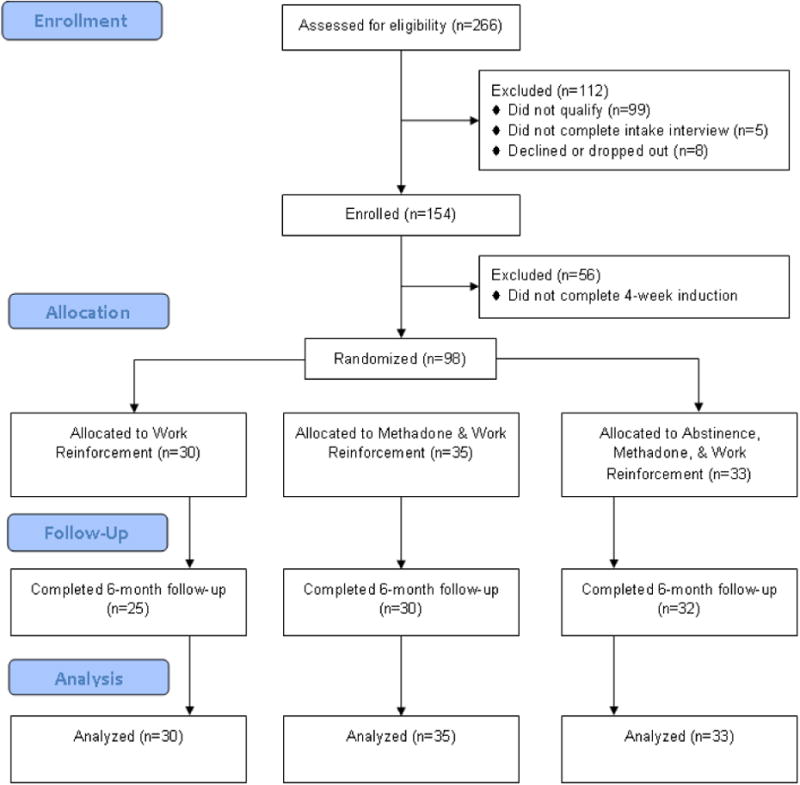

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the study. Enrolled participants were randomly assigned to the Work Reinforcement (n = 30), Methadone & Work Reinforcement (n = 35), or Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement (n = 33) conditions. Total enrollment fell short of the 162 participants called for by a power analysis conducted prior to the study because of time and funding limitations. Table 1 shows participant characteristics at intake. The conditions differed significantly on self-reported days of cocaine use in the past 30 days (p = .02). No additional condition differences were observed.

Figure 1.

The flow of participants through the study. The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at intake.

| Characteristic | Work Reinforcement (n=30) | Methadone & Work Reinforcement (n=35) | Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement (n=33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 44 (9) | 44 (10) | 44 (9) |

| Female, % | 33 | 23 | 45 |

| Black/white/other, % | 63/33/3 | 71/29/0 | 73/27/0 |

| Married, % | 37 | 17 | 27 |

| High school diploma or GED, % | 57 | 51 | 61 |

| HIV positive, % | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Injection drug use, past 30 days, % | |||

| Injected speedball | 67 | 74 | 61 |

| Injected heroin | 97 | 97 | 100 |

| Injected cocaine | 63 | 54 | 55 |

| Past 30 days income, mean (SD), $ | |||

| Employment | 4 (19) | 16 (46) | 14 (35) |

| Welfare | 104 (143) | 119 (133) | 130 (149) |

| Pension, benefits, social security | 56 (223) | 57 (189) | 70 (229) |

| Mate, family, friends | 213 (414) | 183 (410) | 142 (293) |

| Illegal | 963 (1343) | 1028 (1598) | 494 (846) |

| Living in poverty, % | 97 | 100 | 97 |

| Opioid dependent, % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Cocaine dependent, % | 80 | 74 | 55 |

| Days used, past 30 days, mean (SD) | |||

| Heroin | 30 (1) | 30 (1) | 29 (2) |

| Cocaine* | 19 (13) | 13 (12) | 10 (11) |

| $ spent on drugs, mean (SD), past 30 days | 1355 (1316) | 1352 (1304) | 785 (903) |

| Currently on parole/probation, % | 20 | 23 | 15 |

| Lifetime felony conviction, % | 83 | 89 | 85 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, mean (SD) | 18 (6) | 18 (4) | 18 (4) |

| Any Prior treatment, % | 72 | 74 | 76 |

| Desire methadone treatment, % | |||

| Yes | 80 | 94 | 94 |

| No | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Unsure | 17 | 3 | 6 |

| WRAT4 Grade levels, mean (SD) | |||

| Reading | 9 (3) | 9 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Spelling | 7 (3) | 8 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Arithmetic | 6 (2) | 7 (3) | 6 (3) |

Note. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale ranges from 0-30. Higher values indicate more self-esteem.

Significant at the p < .05 level. The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

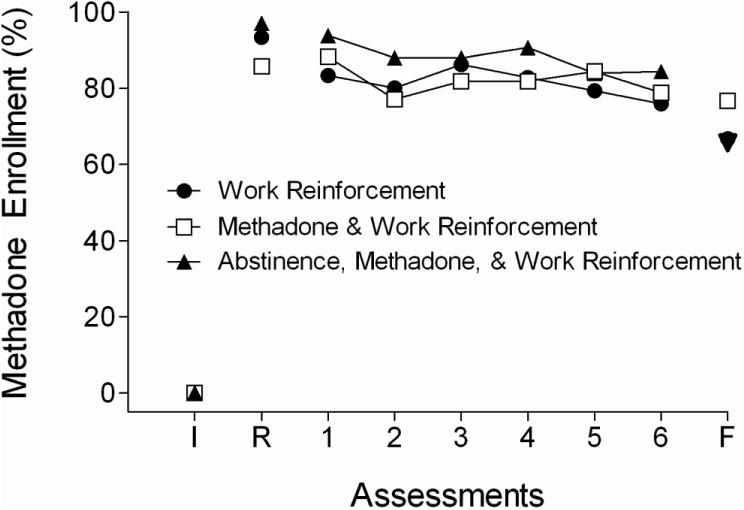

Methadone enrollment and retention

At intake, none of the participants were enrolled in methadone treatment (Figure 2 and Table 2). Some participants reported the use of diverted methadone, which is reflected in the percentage of methadone-positive urine samples at intake. By randomization, methadone enrollment rates were high and similar across conditions–92% of all participants were enrolled in methadone treatment. Although enrollment decreased slightly across the 26-week intervention evaluation period, about 80% of participants were still enrolled at the end of the study and about 70% were enrolled at the follow-up. There were no significant between condition differences in methadone enrollment at any of the assessment time-points.

Figure 2.

The percentage of participants enrolled in methadone treatment (based on participant self-report and confirmations by phone calls to the methadone clinics) at intake (I), randomization (R), the six monthly assessments collected across the 6-month intervention evaluation period, and at the 6-month follow-up (F). The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

Table 2.

Methadone enrollment and opiate, cocaine, and methadone urinalysis results for participants in the Work Reinforcement (Work), Methadone & Work Reinforcement (Methadone), and Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement (Abstinence) conditions.

| Observed condition means (%) | Work vs. Methadone | Work vs. Abstinence | Methadone vs. Abstinence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Work | Methadone | Abstinence | p | OR(95% CI) | p | OR(95% CI) | p | OR(95% CI) | |

| Enrolled in methadone treatment | |||||||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Randomization | 93 | 86 | 97 | 0.33 | 0.43 (0.08-2.39) | 0.51 | 2.28 (0.20-26.58) | 1.12 | 0.19 (0.02-1.69) |

| 30-day assessments | 81 | 82 | 88 | 0.60 | 1.40 (0.40-4.83) | 0.88 | 1.10 (0.32-3.73) | 0.64 | 1.27 (0.36-4.46) |

| 6-month follow-up | 67 | 77 | 66 | 0.42 | 1.64 (0.50-5.45) | 0.94 | 0.96 (0.31-2.92) | 0.57 | 1.72 (0.56-5.24) |

| Methadone positive | |||||||||

| Intake | 13 | 23 | 27 | 0.34 | 1.62 (0.60-4.34) | 0.15 | 2.05 (0.78-5.39) | 0.56 | 0.79 (0.26-2.36) |

| Randomization | 93 | 91 | 94 | 0.77 | 0.76 (0.12-4.89) | 0.93 | 1.11 (0.15-8.39) | 0.95 | 0.69 (0.11-4.45) |

| 30-day assessments | 90 | 84 | 89 | 0.45 | 0.53 (0.10-2.77) | 0.40 | 0.49 (0.09-2.59) | 0.69 | 1.28 (0.41-4.00) |

| 6-month follow-up | 71 | 77 | 72 | 0.63 | 1.35 (0.40-4.59) | 0.93 | 1.05 (0.33-3.39) | 0.58 | 1.08 (0.28-4.19) |

| Opiate negative | |||||||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Randomization | 53 | 51 | 52 | 0.88 | 1.08 (0.41-2.87) | 0.89 | 1.08 (0.40-2.90) | 0.99 | 1.00 (0.38-2.58) |

| 30-day assessments | 54 | 61 | 75 | 0.39 | 0.73 (0.34-1.57) | 0.02* | 0.39 (0.38-0.41) | 0.10 | 1.86 (1.53-2.26) |

| 6-month follow-up | 63 | 57 | 52 | 0.61 | 1.30 (0.39-4.30) | 0.35 | 1.63 (0.83-3.21) | 0.64 | 0.79 (0.23-2.80) |

| Cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Intake | 27 | 23 | 27 | 0.72 | 1.23 (0.40-3.80) | 0.96 | 0.97 (0.32-2.96) | 0.68 | 1.27 (0.42-3.80) |

| Randomization | 40 | 43 | 36 | 0.82 | 0.89 (0.33-2.39) | 0.77 | 1.17 (0.42-3.23) | 0.59 | 1.31(0.49-3.48) |

| 30-day assessments | 32 | 55 | 57 | 0.02* | 0.39 (0.38-0.41) | 0.02* | 0.37 (0.36-0.38) | 0.85 | 1.07 (0.20-5.66) |

| 6-month follow-up | 43 | 43 | 42 | 0.97 | 1.02 (0.15-6.82) | 0.94 | 1.04 (0.16-6.60) | 0.97 | 0.98 (0.15-6.57) |

| Opiate & cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Randomization | 33 | 31 | 24 | 0.87 | 1.09 (0.38-2.09) | 0.43 | 1.56 (0.52-4.69) | 0.51 | 1.43 (0.49-4.17) |

| 30-day assessments | 27 | 44 | 52 | 0.05* | 0.47 (0.43-0.52) | 0.01* | 0.35 (0.35-0.36) | 0.41 | 1.34 (0.60-2.97) |

| 6-month follow-up | 43 | 37 | 30 | 0.61 | 1.30 (0.39-4.30) | 0.29 | 1.75 (1.00-3.06) | 0.55 | 0.73 (0.25-2.16) |

| Assessments collected | |||||||||

| Intake | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Randomization | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 30-day assessments | 89 | 94 | 97 | 0.27 | 1.87 (0.62-5.71) | 0.06 | 3.88 (0.94-16.06) | 0.77 | 0.48 (0.11-2.18) |

| 6-month follow-up | 80 | 83 | 97 | 0.77 | 1.21 (0.34-4.23) | 0.06 | 8.00 (0.90-70.93) | 0.11 | 0.15 (0.12-0.19) |

Note. All missing samples were considered positive. Bold values indicate statistical significance. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between conditions in analyses adjusted for the three stratification variables (i.e., enrolled in methadone treatment, greater than 50% cocaine negative urine samples, and interested in methadone treatment). The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

Participants entered eight different methadone programs, although most (83%) entered treatment on the medical campus where the therapeutic workplace was located. The programs provided an individually determined dose of methadone (about 100 mg) and take-home policies that were consistent with federal regulations. On average, participants enrolled in methadone treatment after 4.6 days of induction (SD = 7.9).

Opiate and cocaine use

Although self-reports of drug use at intake suggest that the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants may have been less severely affected by cocaine use (Table 1), the percentage of opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples from intake, immediately prior to randomization, and during induction were similar across the three conditions (Tables 2 and 3). The Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition provided significantly more urine samples negative for opiates, cocaine and both opiates and cocaine than the Work Reinforcement condition (Figure 3; Tables 2 and 3). The Methadone & Work Reinforcement condition provided significantly more cocaine-negative urine samples than the Work Reinforcement condition. There were no other significant differences between conditions. At the follow-up, there were no significant between-condition differences in opiate and cocaine use.

Table 3.

Opiate and cocaine thrice-weekly urinalysis results and workplace attendance for participants in the Work Reinforcement (Work), Methadone & Work Reinforcement (Methadone), and Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement (Abstinence) conditions during the 4-week induction and the intervention evaluation period.

| Observed condition means (%) | Work vs. Methadone | Work vs. Abstinence | Methadone vs. Abstinence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Work | Methadone | Abstine nce | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | |

| Induction period | |||||||||

| Opiate negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 32 | 30 | 22 | 0.78 | 1.10 (0.57-2.13) | 0.16 | 1.66 (0.82-3.35) | 0.24 | 1.51 (0.76-2.99) |

| Missing missing | 37 | 34 | 26 | 0.72 | 1.13 (0.58-2.21) | 0.16 | 1.67 (0.82-3.40) | 0.27 | 1.48 (0.74-2.95) |

| Cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 33 | 35 | 31 | 0.86 | 0.93 (0.41-2.10) | 0.80 | 1.11 (0.48-2.58) | 0.66 | 1.20 (0.54-2.67) |

| Missing missing | 38 | 39 | 36 | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.43-2.30) | 0.75 | 1.15 (0.49-2.73) | 0.72 | 1.16 (0.51-2.66) |

| Opiate & cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 19 | 17 | 11 | 0.72 | 1.16 (0.51-2.68) | 0.21* | 1.81 (0.72-4.55) | 0.34 | 1.55 (0.62-3.87) |

| Missing missing | 22 | 19 | 13 | 0.71 | 1.18 (0.51-2.73) | 0.22* | 1.79 (0.71-4.51) | 0.37 | 1.52 (0.61-3.79) |

| Days in attendance | 75 | 86 | 83 | 0.14 | 0.65 (0.87-2.72) | 0.03* | 0.52 (1.08-3.48) | 0.46 | 0.80 (0.69-2.31) |

| Collected samples | 86 | 89 | 86 | 0.52 | 0.79 (0.63-2.54) | 0.93 | 1.03 (0.49-1.91) | 0.45 | 1.30 (0.39-1.52) |

| Intervention evaluation period | |||||||||

| Opiate negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 43 | 50 | 65 | 0.37 | 0.75 (0.36-1.55) | 0.01* | 0.40 (0.39-0.40) | 0.05 | 0.53 (0.28-1.00) |

| Missing missing | 57 | 65 | 78 | 0.25 | 0.73 (0.44-1.19) | 0.01* | 0.37 (0.37-0.37) | 0.03* | 0.51 (0.28-0.93) |

| Cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 25 | 44 | 48 | 0.03* | 0.41 (0.39-0.44) | 0.01* | 0.35 (0.34-0.35) | 0.63 | 0.84 (0.42-1.69) |

| Missing missing | 35 | 55 | 56 | 0.04* | 0.45 (0.42-0.48) | 0.04* | 0.44 (0.41-0.48) | 0.96 | 0.98 (0.48-2.02) |

| Opiate & cocaine negative | |||||||||

| Missing positive | 21 | 35 | 46 | 0.07* | 0.49 (0.43-0.56) | 0.01* | 0.31 (0.31-0.32) | 0.19 | 0.64 (0.33-1.25) |

| Missing missing | 29 | 44 | 51 | 0.08* | 0.52 (0.45-0.61) | 0.01* | 0.39 (0.38-0.40) | 0.42 | 0.76 (0.39-1.48) |

| Days in attendance | 68 | 70 | 70 | 0.78 | 0.90 (0.53-2.33) | 0.88 | 0.95 (0.51-2.19) | 0.89 | 1.05 (0.46-1.95) |

| Collected samples | 72 | 74 | 77 | 0.81 | 0.91 (0.51-2.38) | 0.51 | 0.76 (0.59-2.92) | 0.66 | 0.84 (0.55-2.60) |

Note. Bold values indicate statistical significance. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between conditions in analyses adjusted for the three stratification variables (i.e., enrolled in methadone treatment, greater than 50% cocaine negative urine samples, and interested in methadone treatment). For the “missing positive” analyses, missing urine samples were coded as positive for opiates and cocaine. For the “missing missing” analyses, urine samples were not replaced. The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

Figure 3.

The percentage of urine samples negative for opiates (top graphs), cocaine (middle graphs), and both opiates and cocaine (bottom graphs) during the monthly (left panel) and thrice-weekly (right panel) assessments. The data points represent individual participants and the horizontal lines indicate condition means. The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

HIV risk behaviors

At intake, participants reported engaging in various HIV risk behaviors (Table 4). During the intervention evaluation period, reports of sharing needles or works, trading sex for drugs or money, going to a shooting gallery or crack house, and injecting drugs were very low and comparable for the three conditions. These remained at low levels at the follow-up.

Table 4.

HIV risk behaviors for participants in the three study conditions.

| Characteristic | Work Reinforcement | Methadone & Work Reinforcement | Methadone, Abstinence, & Work Reinforcement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared needles or works | |||

| Intake | 17 | 20 | 33 |

| Randomization | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| 30-day assessments | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Traded sex for drugs or money | |||

| Intake | 27 | 14 | 21 |

| Randomization | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 30-day assessments | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Been to a shooting gallery | |||

| Intake | 30 | 37 | 18 |

| Randomization | 3 | 11 | 21 |

| 30-day assessments | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| 6-month follow-up | 8 | 7 | 3 |

| Been to a crack house | |||

| Intake | 20 | 23 | 15 |

| Randomization | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| 30-day assessments | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 6-month follow-up | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Injected anything | |||

| Intake | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Randomization | 77 | 74 | 67 |

| 30-day assessments | 43 | 30 | 36 |

| 6-month follow-up | 32 | 27 | 31 |

Note. The study was conducted in Baltimore, MD from December 2008 to December 2012.

Voucher earnings and attendance

During the intervention evaluation period, Work Reinforcement, Methadone & Work Reinforcement, and Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants earned about the same amount in vouchers [M (SD) = $3370 ($1474), $3638 ($1694), $3073 (1593), respectively] and worked for a similar number of hours [M (SD) = 119 (90), 130 (94), 121 (91), respectively]. There were no significant between-condition differences in the percentage of workdays attended (Table 3).

Discussion

The study was designed to assess whether employment-based reinforcement delivered via the therapeutic workplace could promote enrollment in methadone treatment and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users. The study showed that the therapeutic workplace can promote abstinence from opiates and cocaine. However, direct examination of the effect of employment-based reinforcement in promoting engagement in methadone treatment was precluded because most participants enrolled in methadone treatment during induction, before employment-based reinforcement contingencies were arranged for two of the conditions to enroll in methadone treatment. Participants in all three groups continued methadone treatment throughout and after participation in the therapeutic workplace ended (Figure 2; Table 2).

Four main factors may have contributed to the high methadone enrollment rates. First, the stability and routine provided by attending the therapeutic workplace may have facilitated engagement in methadone treatment. A second key factor may be that participants could use their earnings in the workplace to pay their methadone treatment fees. Reducing treatment costs has been shown to increase treatment entry and retention (Booth et al., 2003, 2004; Jackson, Rotkiewicz, Quinones, and Passannante, 1989). Third, after study enrollment, several participants began interim methadone treatment before being transferred to methadone maintenance, which can increase treatment entry rates (Schwartz et al., 2006; Yancovitz et al., 1991). Finally, many participants in the present study (89%; Table 1) reported a desire for treatment at intake. Booth and colleagues (2003, 2004) have shown that a desire for treatment is associated with higher rates of treatment entry and retention. Future research will have to determine if access to the workplace can promote enrollment in methadone treatment without the addition of employment-based reinforcement contingencies by comparing participants offered induction in the therapeutic workplace to a control condition that is simply referred to methadone treatment.

The Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants provided the highest percentage of drug-negative urine samples, showing that the therapeutic workplace can promote drug abstinence. Although rates of drug abstinence in the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition differed significantly from the Work Reinforcement condition, they did not differ significantly from the Methadone & Work Reinforcement condition. The non-significant difference between the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement and the Methadone & Work Reinforcement conditions is most likely due to the fact that the contingencies were introduced in a sequential fashion. Because of the sequential administration, some of the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement participants were not exposed to the abstinence contingencies or were exposed for a portion of the intervention evaluation period. Specifically, while the evaluation period was 26 weeks, two participants were never exposed to the opiate abstinence contingency and the remaining participants were exposed to the contingency for 10–22 weeks; seven participants were never exposed to the cocaine abstinence contingency and the remaining participants were exposed for 11–19 weeks. An analysis within the Abstinence, Methadone, & Work Reinforcement condition based on participants actually exposed to the abstinence reinforcement contingencies showed that the opiate and cocaine contingencies significantly and selectively increased abstinence from opiates and cocaine, respectively (analyses not shown). Thus, the ability to detect effects of the abstinence reinforcement contingencies in the intent-to-treat analysis appears limited by the sequential administration of those contingencies.

Methadone & Work Reinforcement participants provided significantly more cocaine-negative urine samples than Work Reinforcement participants, despite the fact that there was not a contingency on cocaine use for either condition. We do not fully understand why cocaine use differed between the two conditions. Methadone & Work Reinforcement and Work Reinforcement participants were retained in the study and attended the workplace at a similar rate, thus it is unlikely that the significant difference in cocaine use is due to differences in treatment engagement. Although detailed methadone dosing records were not available for all participants, analysis of the records that were available did not reveal any between-condition differences in the methadone dose nor the percentage of doses accepted.

At the follow-up, there were no between-condition differences in rates of drug abstinence. While some studies have shown that voucher-based abstinence reinforcement can produce increases in drug abstinence that persist after abstinence reinforcement is discontinued (Higgins, Badger, and Budney, 2000; Higgins, Wong, Badger, Ogden, and Dantona, 2000), relapse is common after treatment ends (Dennis and Scott, 2007; Galai et al., 2003; Hser et al., 2001, 2007, 2008; McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien, and Kleber, 2000). Employment-based abstinence reinforcement can maintain drug abstinence over extended periods of time (Silverman et al., 2002; DeFulio et al., 2009); however, it has not reliably promoted abstinence after the intervention is discontinued. The present results support the notion that long-term exposure to abstinence reinforcement is necessary to produce sustained drug abstinence (Silverman et al., 2012).

A few limitations should be noted. First, only participants who completed induction were randomized to a study condition. As noted in Figure 1, 56 participants were excluded due to failure to complete induction. Because access to the workplace was used to reinforce methadone enrollment, only participants who demonstrated that the workplace functioned as a reinforcer were randomized into the study. This may have resulted in a sampling bias in which only participants amenable to methadone treatment attended the workplace and could limit the generality of the results. Second, detailed records of the procedures used at the different methadone clinics were not examined and, therefore, it is unknown to what degree the context in which participants received methadone treatment impacted the study outcomes.

While treatment engagement and drug use were targeted in the present study, participants displayed several other factors relevant to the problem of health disparities. Participants had histories of chronic unemployment, poverty, educational and skill deficits, and criminal behavior in addition to their persistent illicit drug use and failure to access the treatment system. Although some of the results of this study are not fully understood, the high rates of methadone treatment enrollment, the increase in drug abstinence, and the decrease in HIV risk behaviors are highly encouraging. The present study shows that the therapeutic workplace can be attractive to and effective in many out-of-treatment injection drug users, a population in desperate need of effective interventions to address their persistent drug use, HIV risk behaviors, unemployment and poverty.

Highlight.

Most heroin-dependent injection drug users are not enrolled in methadone treatment

Therapeutic workplace participants enrolled in methadone treatment at high rates

Employment-based reinforcement increased abstinence from opiates and cocaine

The therapeutic workplace participants remained in methadone treatment at follow-up

Employment-based reinforcement may need to be sustained long-term to sustain abstinence

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01DA023864, K24DA023186, and T32DA07209 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank Jeanne Harrison for her assistance with data management and study coordination, Jackie Hampton for participant recruitment and assessment, and David Pierce for his help with data analyses.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT01416584

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdala N, Stephens PC, Griffith BP, Heimer R. Survival of HIV-1 in syringes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:73–80. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199901010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tayyib AA, Koester S. Injection drug users' experience with and attitudes toward methadone clinics in Denver, CO. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ball JC, Lange WR, Myers CP, Friedman SR. Reducing the risk of AIDS through methadone maintenance treatment. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29:214–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthwell A, Senay E, Marks R, White R. Patients successfully maintained with methadone escaped human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:957–958. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Corsi KF, Mikulich SK. Improving entry to methadone maintenance among out-of-treatment injection drug users. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:305–311. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Corsi KF, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK. Factors associated with methadone maintenance treatment retention among street-recruited injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Crowley TJ, Zhang Y. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention and effectiveness: out-of-treatment opiate injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski C, Iguchi MY, Pinto F, John D. Public Health Rep. Vol. 113. Washington, D.C.: 1998. Facilitating treatment entry among out-of-treatment injection drug users; pp. 116–128. 1974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bux DA, Iguchi MY, Lidz V, Baxter RC, Platt JJ. Participation in an outreach based coupon distribution program for free methadone detoxification. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:1066–1072. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.11.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplehorn JR, Ross MW. Methadone maintenance and the likelihood of risky needle-sharing. Int J Addiction. 1995;30:685–698. doi: 10.3109/10826089509048753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Dorsey KB, Spitznagel EL, Mager DE. Comparing assessments of DSM-IV substance dependence disorders using CIDI-SAM and SCAN. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41:179–187. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Donlin WD, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement as a maintenance intervention for the treatment of cocaine dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104:1530–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Everly JJ, Leoutsakos JMS, et al. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to an FDA approved extended release formulation of naltrexone in opioid-dependent adults: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Guarinieri M, et al. Meth/amphetamine use and associated HIV: implications for global policy and public health. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Ingram PW, Burks ME, Rachal JV. Effectiveness of streamlined admissions to methadone treatment: a simplified time-series analysis. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26:207–216. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1994.10472268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlin WD, Knealing TW, Needham M, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Attendance rates in a workplace predict subsequent outcome of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in methadone patients. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41:499–516. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Defulio A, Everly JJ, et al. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to oral naltrexone treatment in unemployed injection drug users. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:74–83. doi: 10.1037/a0030743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everly JJ, DeFulio A, Koffarnus MN, et al. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to depot naltrexone in unemployed opioid-dependence adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2011;106:1309–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Gowing L, Marsden J, Ling W, Ali R. Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in HIV prevention. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Jose B, Deren S, Des Jarlais DC, Neaiqus A. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among out-of-treatment drug injectors in high and low seroprevalence cities. The national AIDS research consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:864–874. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galai N, Safaeian M, Vlahov D, Bolotin A, Celentano DD. Longitudinal patterns of drug injection behavior in the ALIVE study cohort, 1988–2000: description and determinants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:695–704. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Anglin MD, Wugalter SE. Patterns and predictors of cocaine and crack use by clients in standard and enhanced methadone maintenance treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:15–42. doi: 10.3109/00952999709001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartel DM, Schoenbaum EE, Selwyn PA, Kline J, Davenny K, Klein RS, Friedland GH. Heroin use during methadone maintenance treatment: the importance of methadone dose and cocaine use. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:83–88. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, et al. A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1218–1224. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Budney AJ. Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:377–386. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Ogden DE, Dantona RL. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Huang D, Chou CP, Anglin MD. Trajectories of heroin addiction: growth mixture modeling results based on a 33-year outcome study. Eval Rev. 2007;31:548–563. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Huang D, Brecht ML, Li L, Evans E. Contrasting trajectories of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use. J Addict Dis. 2008;27:13–21. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge RM. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychol Addict Behav. 1997;11:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- iLearn. 2013 Retrieved October 4, 2013, from http://www.ilearn.com/web/ipass.html.

- Jackson JF, Rotkiewicz LG, Quinones MA, Passannante MR. A coupon program–drug treatment and AIDS education. Int J Addict. 1989;24:1035–1051. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, King VL, Gandotra N, Kolodner K, Brooner RK. Improving treatment enrollment and re-enrollment rates of syringe exchangers: 12-month outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, King VL, Neufeld K, Peirce J, Kolodner K, Brooner RK. Improving substance abuse treatment enrollment in community syringe exchangers. Addiction. 2009;104:786–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber HD. Methadone maintenance 4 decades later: Thousands of lives saved but still controversial. JAMA. 2008;300:2303–2305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Fingerhood M, Svikis DS, Bigelow GE, Silverman K. Monetary incentives to reinforce engagement and achievement in a job- skills training program for homeless, unemployed adults. J Appl Behav Anal. 2013;46:582–591. doi: 10.1002/jaba.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE. Methadone maintenance as HIV risk reduction with street-recruited injecting drug users. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:483–489. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Kang SY, Nwakeze PC, Demsky S. Temporal patterns of heroin and cocaine use among methadone patients. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33:2441–2467. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers B, Degenhardt L, Phillips B. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372:1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejta CL, Bokos PJ, Mickenberg J, Maslar ME, Senay E. Improving substance abuse treatment access and retention using a case management approach. J Drug Issues. 1997;27:329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaline H, Snider E, Petro C, et al. Automated version of the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB): Enhancing the assessment of risk behaviors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:S281–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, et al. Why don't out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programmes? Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles RR, Reyes JC, Colon HM, et al. Effects of combined counseling and case management to reduce HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic drug injectors in Puerto Rico: a randomized control study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image Revised edition. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Highfield DA, Jaffe JH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interim methadone maintenance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:102–109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O'Grady KE, et al. Attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone among opioid dependent individuals. Am J Addictions. 2008;17:396–401. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K. Exploring the limits and utility of operant conditioning in the treatment of drug addiction. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:209–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03393181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO. Maintenance of reinforcement to address the chronic nature of drug addiction. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: six-month abstinence outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:14–23. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Svikis D, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: three-year abstinence outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:228–240. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, et al. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. J Appl Behav Anal. 2007;40:387–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Costatini MF, Wall TL, Gibson DR. Coupons attract high-risk untreated heroin users into detoxification. Drug and Alcohol Depend. 1993;31:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90007-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Ricketts EP, Huettner S, et al. Facilitating entry into drug treatment among injection drug users referred from a needle exchange program: results from a community based behavioral intervention trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, Fiellin DA. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Roberston AM, Strathdee SA. HIV prevention among injection drug users in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:S114–121. doi: 10.1086/651482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. WRAT-3: Wide Range Achievement Test Administration Manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yancovitz SR, Des Jarlais DC, Peyser NP, et al. A randomized trial of an interim methadone maintenance clinic. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1185–1191. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.9.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller ND, Bazazi AR, Velazquez L, Rich JD. Attitudes toward methadone among out-of-treatment minority injection drug users: implications for health disparities. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2009;6:787–797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]