Abstract

Childhood obesity affects approximately 20% of US preschool children. Early prevention is needed to reduce young children’s risks for obesity, especially among Hispanic preschool children who have one of the highest rates of obesity. Vida Saludable was an early childhood obesity intervention designed to be culturally appropriate for low-income Hispanic mothers with preschool children to improve maternal physical activity and reduce children’s sugar sweetened beverage consumption. It was conducted at a large southwestern United States urban health center. Presented here are the methods and rationale employed to develop and culturally adapt Vida Saludable, followed by scoring and ranking of the intervention’s cultural adaptations. An empowered community helped design the customized, culturally relevant program via a collaborative partnership between two academic research institutions, a community health center, and stakeholders. Improved health behaviors in the participants may be attributed in part to this community-engagement approach. The intervention’s cultural adaptations were scored and received a high comprehensive rank. Post-program evaluation of the intervention indicated participant satisfaction. The information presented provides investigators with guidelines, a template, and a scoring tool for developing, implementing, and evaluating culturally adapted interventions for ethnically diverse populations.

Keywords: community engagement, culturally adapted, Hispanics, obesity intervention, preschool children

Approximately one in five U.S. preschool children are overweight or obese (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). Mexican-American preschool children have a disproportionately higher prevalence of obesity (33.3%) than their non-Hispanic Black (28.9%), and non-Hispanic White counterparts (23.8%). Children from low-income families are at higher risk for obesity than children from more affluent backgrounds (Singh, Siahpush, & Kogan, 2010). Childhood obesity often continues into adulthood with consequent obesity-related co-morbidities (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, and psychosocial problems) and increased risk for premature death (Franks et al., 2010).

Early prevention is needed to reduce young children’s risks for developing obesity, especially among at-risk Hispanic preschool children. Health care directives recommend a multi- factorial approach for early childhood obesity prevention that addresses environmental influences and cultural factors in ethnically diverse populations (White House Task Force On Childhood Obesity, 2010). Multiple obesity intervention studies have focused on school-age children and adolescents, but few have been directed to preschool children, and fewer still to low-income high-risk ethnic populations (Bluford, Sherry, & Scanlon, 2007; Small, Anderson, & Melnyk, 2007).

In response to the paucity of obesity interventions studies focused on ethnically diverse preschool children at risk for obesity, we conducted a pilot study to test the feasibility of a culturally appropriate obesity intervention – Vida Saludable – for low-income Hispanic mothers with preschool children. A community engagement approach was used to develop an intervention relevant for the target community supported through a collaborative partnership between two academic research institutions, a community health center, and stakeholders. This may have been an important factor in the study’s findings of improved nutrition and physical activity behaviors. This article presents the methods and rationale used to culturally adapt the intervention, followed by the scoring and ranking of the intervention’s cultural adaptation. To evaluate and rank the intervention’s cultural adaptations, a published scoring system was used. This information provides investigators and community health personnel with guidelines and a template for developing and implementing culturally relevant health promotion interventions for ethnically diverse populations.

Rationale for Cultural Adaptation

Hispanics are the youngest, and fastest growing ethnic group in the United States, experiencing lower incomes and education levels than non-Hispanic whites (Johnson & Lichter, 2008). Thus, many Hispanics have limited English proficiency, low literacy, and low health literacy (limited capacity to obtain and comprehend basic health information) (Cauce & Domenech-Rodrigues, 2002). They also encounter health disparities including limited access to medical insurance, healthcare resources, and culturally appropriate health promotion programs.

To help reduce health disparities, culturally appropriate and relevant health promotion programs are needed for ethnically diverse populations to improve health behaviors and promote participant recruitment, engagement, and retention (Bender & Clark, 2011). Culturally appropriate obesity and diabetes interventions are shown to be effective in improving health behaviors within Hispanic communities (Deitrick et al., 2010; Haire-Joshu et al., 2008). In contrast, culturally inappropriate interventions can be ineffective, perplexing, or offensive (Marin, 1993). For example, focusing on obesity may be offensive and counterproductive within the Hispanic culture, which perceives plump children as healthy (Bender & Clark, 2011). Instead, focusing on raising strong healthy children may be more acceptable and congruent with Hispanic cultural beliefs (Cauce & Domenech-Rodrigues, 2002).

Vida Saludable’s program design was based on the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Working Group Report on Future Research Directions in Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment (NHLBI, 2007) recommendation for early childhood obesity interventions. NHLBI’s recommendations included: (a) parental involvement for improving children’s diet and physical activity (PA), (b) multi-level community-based participation, and (c) culturally appropriate interventions. Evidence supports involving parents in interventions to promote healthy behaviors in young children (Summerbell et al., 2012). Parents influence their children’s lifelong behaviors. Children are likely to mirror their parents’ nutrition and activity behaviors (Haire-Joshu et al., 2008; Ruiz, Gesell, Buchowski, Lambert, & Barkin, 2011).

Modifying obesity promoting behaviors is an important strategy for reducing child obesity incidence. Evidence suggests small, simple, manageable, and easily measureable changes in diet and PA may be effective strategies for weight control in children and adolescents (Rodearmel et al., 2007, NHLBI, 2007). Increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB, e.g., soda) and decreased physical activity has been observed in children of all ages (Rey- Lopez, Vicente-Rodriguez, Biosca, & Moreno, 2008; Wang, Bleich, & Gortmaker, 2008), particularly Hispanic preschool children. SSB consumption was found to be associated with increased weight in Mexican-American preschool children (Warner, Harley, Bradman, Vargas, & Eskenazi, 2006). Hispanic immigrant children were reported twice as likely to be physically inactive compared to native-born non-Hispanic white children (Singh, Yu, Siahpush, & Kogan, 2008). Replacing high caloric SSB with water and low-fat milk to reduce total energy intake (Wang, Ludwig, Sonneville, & Gortmaker, 2009), and encouraging PA to improve overall energy balance and reduce obesity risks are recommended (Rodearmel et al., 2007).

Cultural Adaptation Framework

Designing culturally appropriate intervention programs requires cultural sensitivity, taking into account the ethnic/cultural characteristics of the target population. This includes cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors; social dynamics and family structure; literacy and education level; and economic status and the built environment (Bender & Clark, 2011). The process of culturally adapting Vida Saludable incorporated aspects of Resnicow, Branowski, Ahluwalia, and Braithwaite’s (1999) surface versus deep structure adaptations; Kreuter and associates’ (2003) five categorical strategies for adaptation and concepts of targeting and tailoring; and Eremenco, Cella, and Arnold’s (2005) translation guidelines for program materials. Table 1 provides a description of the cultural adaptation framework.

Table 1.

Cultural Adaptation Strategies

| Adaptation Strategies | Description | Hispanic Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Surface structure | Use observed visual and audio cues or superficial characteristics of the culture | Use pictures of popular Hispanic persons, scenes, foods, and music |

| Deep structure | Use comprehensive cultural perceptions of the world that address idiosyncratic differences between groups/subgroups. Requires community assistance and more time & effort. | Formulate program around family, which is central to Hispanic identity and values; avoid conflict w/beliefs, e.g., plump children are healthy; accommodate patriarchal tradition by including father |

| Targeting | Use approaches that best communicate, influence, or reach the entire intended population. | Health promotion program facilitated by ethnically similar individuals (e.g., promotora, a trusted community health worker who knows the culture and language) |

| Tailoring | Use approaches that refine and personalize an intervention or message for an individual or subgroup. | Subgroup: Adapt surveys using visual images w/simple commonly used Spanish words for a low-literate Spanish speaking group Individual: Meet in familiar surroundings like home or family clinic |

| Kreuter et al’s Categorical Strategies | ||

| Peripheral | Same as surface structure | See example above |

| Evidential | Integrate scientific evidence pertaining to culture (e.g. specific health issues) | Incorporate education message that Hispanics are at high risk for diabetes |

| Constituent Involving | Involve community stakeholders (leaders, community members) who understand the culture’s surface and deep structure | Employ community engagement approach w/promotora & local Hispanics to develop and refine intervention (focus groups, etc.) |

| Socio-cultural | Integrate social and cultural norms, and values to create a meaningful and relevant intervention program | Supplement program with social services and childcare for low-income Hispanics participants |

| Linguistic | Develop program materials and measurement instruments that are culturally equivalent to original source constructs and concepts | Follow rigorous translation guidelines, taking into account the participant’s education and literacy levels, and regional language |

Methods

Study design

This pilot study was designed to test the feasibility of Vida Saludable – a promotora-led 9-month intervention program for Hispanic mothers with 3- to 5-year-old children. We used a sequential mixed method (qualitative to quantitative) design. A community engagement approach employed qualitative methods (focus groups, individual interviews, and stakeholder input) to culturally adapt the intervention. The study focused on mothers as the principle advocates for improving health behaviors in their children. The intervention program goals were to: (a) decrease children’s consumption of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) and increase consumption of healthy beverages (water and low-fat milk), and (b) increase maternal walking (pedometer step-counts) to role model and engage children in physical activity. This paper’s primary focus is on the methods and rationale used to adapt the intervention to be culturally appropriate for the target population; therefore, we do not focus on the quantitative findings of the study. Study results are reported elsewhere (Bender, Nader, Kennedy & Gahagan, 2013).

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of California San Diego. All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human subjects were followed.

Setting

The study was conducted at a large urban health center in the southwestern United States providing health and social services to more than 60,000 low-income Hispanics. The health center functions as a resource and social center for community members. The center uses promotoras to facilitate health promotion programs (e.g., diabetes, HIV, and cardiovascular disease). Promotoras are trained local health workers who know the culture, speak the language, and are trusted members of the community (Perez and Martinez, 2008). These programs have been well received and well attended by the Hispanic community for over 30 years.

Sample and Recruitment

Potential participants were identified through the health center’s electronic database and contacted by phone. Inclusion criteria were low-income Hispanic mothers with 3- to 5-year-old children. Exclusion criteria were children on special diets or unable to swallow liquids, and mothers and children unable to walk together. Interested participants received a home visit by the promotora for study information and enrollment. A purposive sample of N=43 mother-child dyads was enrolled. Thirty-three mother-child dyads completed the intervention program. Participant dropouts were due to work schedules precluding program attendance.

All participants were Mexican. Maternal mean age was 27.0 years. Mothers spoke primarily Spanish (97%), lived at, or below the poverty level (88%), lived in the United States 7 or fewer years (88%), had 4 or fewer years of education (76%), and were medically uninsured (97%). Children’s mean age was 3.6 years and over half (52%) were female. All children were medically insured and not attending school at enrollment.

Vida Saludable Intervention

A community engagement approach was used to develop Vida Saludable. Stakeholders were involved with every aspect of the design, development, and cultural adaptation of the intervention program.

The intervention was a two-phase program. Phase 1 included four biweekly interactive group lessons for the mothers focused on healthy drinks (water and 1% low-fat milk), ways to limit SSB (soda, 100% juice, other sugary drinks) and encourage physical activities (e.g. walking), and parental modeling of healthy behaviors. The promotora first modeled mother/child physical activities (e.g., dancing and walking together). Mothers and children then practiced these activities. Healthy refreshments were served (e.g., fresh vegetables and fruit, water, and 1% low-fat milk). Mothers were also given pedometers to measure their walking steps. Instruction and practice sessions were provided on how to use and store the pedometers. Mothers were asked to walk at least 30 minutes a day with their children and bring the pedometer to all the meetings.

Following the four lessons, phase 2 included six monthly community group activities to reinforce target behaviors. Community group activities included field trips to: (a) local parks for group trail walks and games, (b) grocery stores to identify affordable healthy drinks, and (c) a fast-fast food restaurant to identify healthy food choices. A cooking class on preparing healthy cultural meals was also included.

Cultural adaptation process

Development of a culturally relevant intervention was a three-step process. First, we solicited feedback during stakeholder meetings, the pre-program focus group, and the pilot test of survey instruments. Second, stakeholders and investigators collaboratively assessed and incorporated the feedback into the intervention program. Third, following intervention implementation and study completion, post-program focus groups solicited participant evaluations of the intervention’s relevance, cultural appropriateness, and suggestions on improvements for future studies.

Pre-program adaptations

Stakeholders recommended a promotora-led intervention. To facilitate the intervention program, a promotora was recruited from the health center’s health promotion department. Investigators trained the promotora to recruit and enroll participants, conduct the lessons and group activities, provide telephone follow-up and support, and assist investigators with data collection. A Spanish-speaking investigator was present at each session to ensure appropriate implementation.

In the pre-program focus group, many participants reported knowing a family member or acquaintances diagnosed with diabetes or high blood pressure. Thus, program lessons emphasized the importance of improving health behaviors to reduce Type 2 diabetes, common among Hispanics (Caballero, 2007). To avoid any negative stigmatization related to and/or insensitivity to the cultural belief regarding the body size of children, the overall health promotion message focused on “raising strong healthy children,” rather than on obesity. During pre-program focus group interviews, participants also expressed a desire to learn about local safe walking routes, where to buy lower-cost foods, and how to prepare healthy meals. The community group activities were therefore modified to include a safe trail walk in a local park, a field trip to a local discount super market, and a cooking class using healthy cultural foods (e.g., black beans and corn tortillas).

Health promotion coordinators, clinic providers, and promotoras reviewed pictures of Hispanic children (surface structure) and typical cultural beverages (e.g. fresh pineapple drink with added sugar) used in program materials, then helped translate program materials, such as consent forms, handouts, and surveys, following published guidelines. To accommodate Spanish-speaking participants with low-literacy skills and limited English proficiency, the program materials were further tailored to incorporate simple Spanish words commonly used by this population.

Most of our low-income participants could not afford childcare and wanted access to their children during the program meetings. Therefore, we developed a children’s program focused on healthy beverages and PA to run concurrently with the mothers’ lessons. Lessons were conducted in a large meeting room with a sliding partition kept slightly open so mothers and children could see one another.

Mid-program adaptations

We made several program modifications during the course of the intervention. Extended family members (e.g. grandparents and aunts) accompanied many mother-child dyads to meetings. We understood that the Hispanic culture views family as important (deep structure) and central to their identity (Cauce & Domenech-Rodrigues, 2002; Elder et al., 2009). The program was therefore modified to allow extended family members to attend. Two fathers arranged their days off to coincide with the community group activities in order to participate, and several other fathers started walking with the mothers and children. For PA, we initially planned a one-time mother-child dancing lesson to Mexican music. All participants reported enjoying dancing so much that we modified the program, providing a music CD to promote this physical activity at home, with the entire family.

During meetings, many participants reported needing assistance with non-program health and social services (e.g., clinic and social service appointments). To address these important needs, we arranged for auxiliary services following the meetings.

Survey instrument adaptations

Community stakeholders and four research experts in childhood obesity and ethnically diverse populations reviewed several validated survey instruments (Cullen, Watson, & Zakeri, 2008; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 2009; National Institutes of Health, 2008) measuring nutrition and PA, but found them to be culturally and linguistically unsuitable for our study population. Using these validated instruments as a foundation, the experts developed two customized survey instruments, the Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ) and a Program Evaluation Survey (PES). The research experts and stakeholders provided content validity with special attention to culture, low literacy, and education levels. The surveys were forward and back translated into Spanish using independent translators following published guidelines (Eremenco et al., 2005). Both surveys were pilot tested in a community population similar to our target audience. Comprehensive interviews regarding the constructs and concepts of each question were conducted with a non-study homogenous population. Based on the pilot test results, individual comprehensive interviews, and stakeholder input, the surveys were further adapted and linguistically tailored. More psychometric testing is needed to extensively validate the survey instruments.

Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ)

This 17-item survey measured children’s consumption of SSB (e.g., soda [not diet or sugar-free], 100% fruit juice, other sugary drinks [e.g., punch, sports drinks, and flavored juices]), water, and low-fat milk. Measures included amount (ounces per day) and frequency (servings per day). Mothers were trained to accurately report children’s beverage consumption.

Program Evaluation Survey (PES)

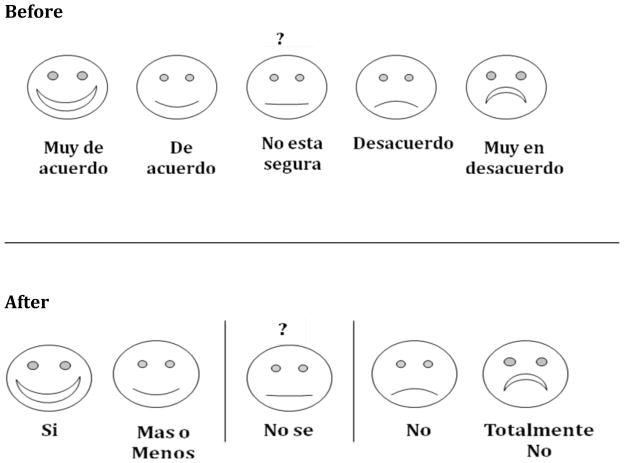

This 17-item tool measured maternal beliefs and knowledge regarding beverage consumption and PA and self-efficacy in modeling health behaviors. The PES uses a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 0-strongly agree to 5-strongly disagree). Comprehensive interviews with participants during the pre-program pilot test of surveys lead to an innovative adaptation of the Likert scale appropriate for a Mexican population with low education and literacy skills. Based on the input, we incorporated very simple, commonly used Spanish words and pictures of faces for the range of responses. Figure 1 presents the evolution of the linguistically tailored Likert scale. Participants and the promotora reported they liked and understood the linguistically tailored Likert scale better than the initial version. This was validated by fewer missing data elements in subsequent surveys.

Figure 1.

Cultural adaptation of Likert scale before and after stakeholder feedback

Based on participant requests, the surveys were administered in Spanish along with instruction on taking the survey. To assist those with low-literacy skills, each question was projected overhead and read aloud by the promotora along with individual assistance.

Post-program evaluation

Following completion of the 9-month study, we conducted a post-program focus group interview for participants to evaluate the program. Overall, participants enjoyed the program, bonded well with other participants, and continued to meet informally to socialize, exchange recipes, or walk. Many requested additional health promotion programs, including a family-oriented program and more community group activities, particularly park-outings, trail walks, and field trips to local grocery stores. Participants were highly complimentary of the promotora who facilitated the program and the support she provided, particularly her ability to answer their many questions about the surveys, educational materials, and program activities. They particularly liked using the pedometers to measure their walking progress. Participants reported organizing their own walking groups and friendly walking competitions. For future programs, they recommended having pedometers for the children. Overall, participants reported satisfaction with the program.

Cultural Adaptation Scoring System

Bender’s scoring system (Bender & Clark, 2011) was employed to analyze, score, and rank the intervention’s cultural adaptations for the target population. Table 2 provides a blueprint for the Bender scoring system. Scores are based on use of the following components: (a) the five cultural adaptation strategies categories: peripheral, evidential, constituent-involving, socio- cultural, and linguistic adaptation strategies; (b) surface and deep structure concepts; and (c) target versus tailoring approaches. Component scores were generated and summed for a total adaptation score. The total score was normalized and the intervention was assigned a relative cultural adaptation rank (minimal ≤50%, moderate >50% and ≤75%, comprehensive >75%).

Table 2.

Bender Cultural Adaptation Scoring System Tool

| Adaptation Strategy Category | Scoring Method and Strategy Examples | Category Base Score (Max) | Category Tailored Score (Max) | Category Total Score (Max) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | Base Score = 1 if strategy used | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ethnic food models | |||||

| Visual aids/colorful pictures | |||||

| Puppet food characters | |||||

| Tailored Score* | |||||

| Evidential | Base Score = 1 if strategy used | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Risk of Type 2 diabetes for obese Hispanic children | |||||

| Risk of sexual transmitted disease for sexually active teens | |||||

| Tailored Score * | |||||

| Constituent-involving | Base Score = 2 if strategy used | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Lay health care workers, culturally sensitive staff | |||||

| Focus groups of target group members | |||||

| Bilingual/bicultural interviewers, educators, etc. | |||||

| Community participatory approach | |||||

| Tailored Score * | |||||

| Socio-Cultural | Base Score = 2 if strategy or concept used | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Incorporating input from stakeholders | |||||

| Incorporating feedback from pilot-tests | |||||

| Child care | |||||

| Reflecting culture (e.g., norms, beliefs, values and SES) | |||||

| Tailored Score * | |||||

| Linguistic |

|

2 Mat. | 1 | 5 | |

|

|

2 Instr. | ||||

| Tailored Score * | |||||

| Category Total Score = Base Score + Tailored Score | |||||

| Total Adaptation Score = Σ Category Total Scores | _____ | _____ | _____ | ||

| Max | Max | Max | |||

| 10 | 5 | 15 |

Tailored Score: None = 0, Group = .33, Subgroup = 0.67, Individual = 1

V & R = valid and reliable Σ = Sum Mat. = Program materials Instr. = Instrument

Bender MS, Clark M. Cultural Adaptation for Ethnic Diversity: A Review of Obesity Intervention for Preschool Children. California Journal of Health Promotion. 2011 Dec;9(2):40–60.

Scoring Results

Table 3 presents Vida Saludable’s individual adaptation component scores, total score, and rank. The intervention received a normalized score of 89%, falling into the “comprehensive” rank for overall cultural adaptation; and scored particularly high for socio-cultural and linguistic strategies and moderate to high in the remaining three strategy categories.

Table 3.

Vida Saludable’s Cultural Adaption Score and Rank

| Peripheral Score B+T |

Evidential Score B+T |

Constituent-involving Score B+T |

Socio-cultural Score B+T |

Linguistic Score Mat. B + Instr. B +T |

Total Score | Normalized Score (Total score/Total Max score = %) | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation** | Adaptation** | Adaptation** | Adaptation** | Adaptation** | |||

| Pictures Foods Music | Type 2 diabetes | promotora participants focus group | child program auxiliary services | all Mat. 2 surveys | |||

| 1 + .67 | 1 + .33 | 2 + .67 | 2 + 1 | 2 + 2 + .67 | 13.34 | 89% | Comprehensive |

B + T = Base + Tailored scores

Mat. = program materials

Instr. = instruments

Total Max score = 15

Comprehensive = normalized score > 75%

Adaptations tailored to subgroup

Vida Saludable was culturally adapted and tailored for a Hispanic subgroup. All five cultural adaptation strategy categories were employed. Peripheral strategies included pictures of Hispanic children and families in program materials. Tailoring involved incorporating common cultural foods and meeting at familiar and accessible community locations. Evidential strategies incorporated education on prevention of Type 2 diabetes (common in Hispanic populations) (Caballero, 2007) to motivate health behavior change. Constituent involvement strategies solicited stakeholder input and focus group feedback. Recommendations were collaboratively assessed and incorporated. Socio-cultural strategies addressed cultural values by extending program attendance to family members. Cultural tailoring, per participant request, included childcare and supplemental health and social services assistance. Linguistic strategies followed published translation guidelines. Surveys were linguistically tailored to more effectively address participant education and literacy levels.

Discussion

Vida Saludable incorporated multiple cultural adaptation strategies including a tailored program for a primarily Spanish-speaking Mexican immigrant population with low literacy, education, and socioeconomic levels. There are several indications the efforts to adapt and tailor this intervention were effective, including a high retention rate (77%), high levels of satisfaction, requests for similar programs with additional community activity, and high comprehensive rank.

A recent systematic review of interventions to improve PA among African Americans found culturally adapted interventions had higher participant satisfaction, engagement, and retention rates compared to non-culturally adapted interventions (Whitt-Glover & Kumanyika, 2009). Cultural modifications applied to Vida Saludable may have influenced high levels of satisfaction demonstrated by the excellent participant retention and program completion rate of 77%. Many non-enrolled community members also wanted to participate in the program, attracted by the positive reports circulating through the community grapevine. Dumak and colleagues noted, in order to be effective and beneficial, parenting interventions for low- acculturated, -educated, and -literate Hispanic groups required more extensive cultural adaptation (Dumka, Lopez, & Carter, 2002). Comprehensive efforts to make Vida Saludable understandable, appealing, and relevant were validated by participant post-program evaluations demonstrating high program satisfaction, requests for more similar programs with additional community activities, and approval of the linguistically tailored surveys.

When stakeholder input and feedback are followed with immediate intervention modifications, recipient satisfaction can be achieved (Dumka et al., 2002). For example, we suspect incorporating a promotora-facilitated program may have enhanced the relevance of the health promotion messages in fostering improved health behaviors and encouraged participant retention and engagement. Likewise, provisions for auxiliary services such as child-care and health and social services may have eliminated barriers to participation and improved satisfaction.

Limitations and strengths

Specific program adaptations and linguistic tailoring made to Vida Saludable may not be generalizable to other populations or community settings. However, the cultural adaptation process and strategies used are generic and globally applicable to other ethnic populations and contexts. Using Krueter and colleagues’ (2003) five generic cultural adaptation categories improved program fit for our population while maintaining the study’s core theoretical health behavior change constructs based on social cognitive learning theory (Bandura, 1989) and the health promotion model (Pender & Pender A, 1987).

Implications for policy

Currently there are multiple published guidelines for culturally adapting programs and materials. National organizations, such as the Institute of Medicine and National Institutes of Health should endorse standardized guidelines for culturally adapting interventions and instruments. One suggestion is for funding agencies to require grantees to provide a detailed outline of the plan to culturally adapt their intervention and program materials for the intended ethnic groups. This would help emphasize the importance of culturally adapting intervention programs to reduce health disparities for ethnically diverse populations.

Implications for nursing practice

Nurses in the public health arena can be particularly effective in helping to prevent childhood obesity and reduce health disparities for at risk ethnic population through advocacy, clinical practice, and research/administration. In collaboration with community organizations at all levels (schools, health. and government) nurses can advocate for policies that (a) improve community programs providing access to healthy food and promoting physical activities to reduce obesity risks; and (b) insure health services, health promotion programs, and education materials are culturally appropriate and relevant for ethnically diverse populations. In clinical practice, nurses can develop and augment their cultural sensitivity skills for patient care through cultural competence continuing education courses, professional meetings, and practice evaluations designed to measure cultural sensitivity. Nurse scientists have the opportunity to move to the forefront of research related to early childhood obesity. As members of multidisciplinary community-based research teams, nurse scientists can play a significant role to help develop, implement, and evaluate culturally appropriate obesity prevention intervention programs. They can also provide recommendations to promote the relavancy of programs for target ethnic groups to improve the quality of the health promotion program for these populations.

Future research

Currently, there are studies on the effectiveness of culturally appropriate and promotora-led interventions (Ayala et al., 2010; Elder, Ayala, Parra-Medina, & Talavera, 2009). Nonetheless, it is still not known which types of adaptation strategies contribute most to efficacy and efficiency. Although our study’s quantitative results (reported elsewhere and under journal review) provided evidence for improving health behaviors in a Mexican population, a comparative study with a non-culturally adapted intervention should be conducted to help identify which types of cultural adaptation strategies contribute most to the efficacy and efficiency of the intervention. Finally, a future larger, longer, randomized control trial should be conducted to further test the feasibility of the Vida Saludable intervention in sustaining long- term health behavior change.

Conclusion

We proffer two observations regarding the cultural adaptation of Vida Saludable – one on the process and another on effectiveness. The process for culturally adapting, linguistically tailoring, and evaluating Vida Saludable provides a useful template for other intervention studies. To this end, the Bender scoring system (Bender & Clark, 2011) is a helpful and practical tool. First, it provides a road map for the development and implementation of culturally adapted intervention programs. Second, it provides a systematic method for evaluating the level of an intervention’s cultural adaptation appropriateness.

Vida Saludable exemplified a community engagement approach to successfully culturally adapt and linguistically tailor a childhood obesity intervention program for low-income Hispanic mother-child dyads. It can be argued the term “successful” is somewhat arbitrary. However, Evans (2003) proposed a hierarchy of evidence focusing on three dimensions of success for a study intervention: effectiveness, appropriateness, and feasibility. Vida Saludable’s intervention effectiveness is evidenced by positive participant evaluations of the program and statistically significant findings of improved outcomes (Bender et al., In press). Intervention appropriateness is supported in diligent compliance with multiple evidence-based guidelines for cultural adaptations and the high, comprehensive ranking on the Bender adaptation scoring system. Finally, feasibility of the intervention program is supported by the strong subjective and objective evaluation findings as well as the extent and character of the adaptations made.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UC San Diego Comprehensive Research Center in Health Disparities, [Grant Number 5 P60 MD 0002200] National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Manuscript preparation was supported by the University of California San Francisco, Family and Community Health Nursing Post-doctoral Fellowship, Nursing Research Training Program in Symptom Management, Institutional National Research Service Award (NRSA) from the National Institute of Nursing Research at NIH, [#2 T32 NR07088-16].

Our deepest gratitude goes to our community partners, Vista Community Clinic, and the stakeholders, for their invaluable contribution to this research project. We thank Philip R. Nader, MD, Professor Emeritus, Anita Hunter, RN, PhD, PNP, FAAN and Kathy S. James RN, DNSc, FNP, FAAN for their invaluable assistance with the development of Vida Saludable; and to Daniel M. Bender for editing and technical support.

Contributor Information

Melinda S. Bender, Email: melinda.bender@ucsf.edu, University of California San Francisco, Department Family Health Care Nursing, 2 koret Way. N411Y, Box 0606, San Francisco, CA 94143-0606, Ph: (415) 466-6082, Fax: (415) 466-6082.

Mary Jo Clark, Email: clark@sandiego.edu, University of San Diego, School of Nursing, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA 92110-8492, Ph (619) 260-4574.

Sheila Gahagan, Email: sgahagan@ucsd.edu, University of California San Diego, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Child Development and Community Health, 9500 Gilman Drive, #0927, La Jolla, CA 92093-0927, Ph: (619) 681-0673, Fax: (619) 681-0666.

References

- Ayala GX, Elder JP, Campbell NR, Arredondo E, Baquero B, Crespo NC, Slymen DJ. Longitudinal intervention effects on parenting of the Aventuras Para Ninos study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.038. S0749-3797(09)00748-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bender MS, Clark M. Cultural adaptation for ethnic diversity: A review of obesity interventions for preschool children. California Journal of Health Promotion. 2011;9(2):40–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender MS, Nader PR, Kennedy C, Gahagan S. A cultural appropriate intervention to improve health behaviors in Hispanic mother-child dyads. Child Obesity. 2013;9(2):157–163. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluford DA, Sherry B, Scanlon KS. Interventions to prevent or treat obesity in preschool children: A review of evaluated programs. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1356–1372. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.163. 15/6/1356 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero AE. Type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic or Latino population: Challenges and opportunities. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 2007;14:151–157. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32809f9531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce A, Domenech-Rodrigues M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KW, Watson K, Zakeri I. Relative reliability and validity of the Block Kids Questionnaire among youth aged 10 to 17 years. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitrick LM, Paxton HD, Rivera A, Gertner EJ, Biery N, Letcher AS, et al. Understanding the role of the promotora in a Latino diabetes education program. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20:386–399. doi: 10.1177/1049732309354281. 20/3/386 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Carter SJ. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, Talavera GA. Health communication in the Latino community: Issues and approaches. Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:227–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. 28/2/212 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Hierarchy of evidence: A framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:485–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904130. 362/6/485 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Food frequency questionnaire. 2009 Retrieved Aug. 2008 from http://sharedresources.fhcrc.org/documents/beverage-and-snack-questionnaire.

- Haire-Joshu D, Elliott MB, Caito NM, Hessler K, Nanney MS, Hale N, et al. High 5 for Kids: The impact of a home visiting program on fruit and vegetable intake of parents and their preschool children. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.016. S0091-7435(08)00159-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Lichter DT. Natural increase: A new source of population growth in emerging Hispanic destinations in the United States. Population and Development Review. 2008;34:327–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00222.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G. Defining culturally appropriate community interventions: Hispanics as a case study. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:149–161. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199304)21:2<149::AID-JCOP2290210207>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Working Group Report on Future Research Directions in Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment. Washington. DC: DHHS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. We Can! Ways to enhance children’s activity and nutrition, energize our families. Bethesda, MD: DHHS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pender NJ, Pender AR. Health promotion in nursing practice. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Perez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):11–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842. AJPH.2006.100842 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Lopez JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Biosca M, Moreno LA. Sedentary behaviour and obesity development in children and adolescents. Nutrition Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease. 2008;18:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.07.008. S0939-4753(07)00169-X [pii] doi:0.1016/j.numecd.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Stroebele N, Smith SM, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Small changes in dietary sugar and physical activity as an approach to preventing excessive weight gain: The America on the Move family study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e869–879. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2927. 120/4/e869 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz R, Gesell SB, Buchowski MS, Lambert W, Barkin SL. The relationship between Hispanic parents and their preschool-aged children’s physical activity. Pediatrics. 2011;127:888–895. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1712. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Rising social inequalities in US childhood obesity, 2003–2007. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.008. S1047-2797(09)00324-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Yu SM, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. High levels of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviors among US immigrant children and adolescents. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:756–763. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.8.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small L, Anderson D, Melnyk BM. Prevention and early treatment of overweight and obesity in young children: A critical review and appraisal of the evidence. Pediatric Nursing. 2007;33:149–152. 155–161, 127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerbell CD, Moore HJ, Vogele C, Kreichauf S, Wildgruber A, Manios Y, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the development of obesity prevention programs targeted at preschool children. Obesity Reviews. 2012;13(Suppl 1):129–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1604–1614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. 121/6/e1604 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Ludwig DS, Sonneville K, Gortmaker SL. Impact of change in sweetened caloric beverage consumption on energy intake among children and adolescents. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(4):336–343. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.23. 163/4/336[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner ML, Harley K, Bradman A, Vargas G, Eskenazi B. Soda consumption and overweight status of 2-year-old Mexican-American children in California. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1966–1974. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.230. 14/11/1966 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House Task Force On Childhood Obesity. Solving the problem of childhood obesity within a generation. In: WHTFOC, editor. Obesity. Washington, DC: Executive Office Of The President Of The United States; 2010. pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Whitt-Glover MC, Kumanyika SK. Systematic review of interventions to increase physical activity and physical fitness in African-Americans. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(6):S33–56. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.070924101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]