ABSTRACT

A 9-month-old intact female Yorkshire terrier dog was presented with episodic partial seizure-like cramping of the limbs. The patient’s episodes began six months previously; the interval between episodes became shorter, and the duration of the episodes increased. Various tests including neurologic examination, blood examination, abdominal radiography, ultrasonographic examination, angiographic computed tomography (CT) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detected no remarkable changes. After these tests were conducted, the patient’s condition was suspected to be canine epileptoid cramping syndrome (CECS), which could be a form of paroxysmal dyskinesia (PD), and as a trial therapy, Science Diet k/d (Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Topeka, KS, U.S.A.) was prescribed. The clinical signs were dramatically reduced after diet therapy, and we diagnosed the patient with CECS. This is the first case report of CECS in a Yorkshire terrier dog.

Keywords: CECS, cramping, k/d, paroxysmal dyskinesia, Yorkshire terrier

Muscle cramps are briefly prolonged, involuntary, forceful and painful muscle contractions lasting from seconds to mins [10, 11, 13, 14] that could be accompanied by palpable knotting of muscle with abnormal bending of the affected joint [14]. Cramps are associated with high rates of repetitive firing of motor units in a muscle and produce action potentials of nerve terminals; only a few muscle fibers are involved during cramping, while many fiber bundles are involved in voluntary muscle contraction [6, 9]. This electronic activity has been referred to as “cramp discharge” [8]. Most cramps occur in patients with hyperactivity of the peripheral nerve terminals or central nervous system (CNS) rather than in patients with primary muscle disease in dogs [13]. Lower motor neuron disorders (peripheral neuropathies, nerve root compression, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and polio), electrolyte and fluid abnormalities (hepatic cirrhosis, hemodialysis and high ambient temperatures) and metabolic disorders (pregnancy, hypothyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism and diabetes mellitus) are commonly reported as causes of muscle cramping in human medicine [8, 12, 13]. In veterinary medicine, muscle cramping most likely occurs with the same features and clinical signs as those described in human medicine, but the animal cannot complain of painful muscle cramps; therefore, it has rarely been documented as a presenting clinical sign [2, 13, 15].

Hypertonicity syndromes characterized by clinically, sudden and reversible episodes of limb hypertonicity, possible cramping, and, in some cases, muscle rippling have been observed [13]. This hypertonicity syndrome was first observed in young Scottish terriers and was called “Scottie cramps” [2]. Previous studies showed similar clinical signs in Cavalier King Charles spaniels, springer spaniels and wheateon terriers [7, 13, 16]. The term “canine epileptoid cramping syndrome” (CECS) was first used for Border terriers in 2012 and is characterized by a paroxysmal cramping or hypertonicity syndrome [1, 3]. Still, few cases have been reported in veterinary medicine, and CECS is currently being researched [3]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of a Yorkshire terrier that showed the same spectrum of clinical signs described in CECS.

A 9-month-old intact female Yorkshire terrier dog, weighing 2.5 kg, presented with episodic partial seizure-like cramping of the limbs. The patient’s history revealed that these episodes began six months previously. The interval between episodes became shorter, and the duration of the episodes decreased. The patient showed clinical signs four times a day, and the duration of each episode was slightly over 30 min just before visiting the clinic. Partial seizure was suspected based on the clinical signs at first presentation. However, all characteristics including gait were normal between episodes, and the dog was conscious and responsive to the owners during the episodes. The patient’s muscle tone was hypertonic, and showed sustained and painful involuntary contractions with bending of the affected joint. The general features of the episodes were similar to those of cramping syndrome (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical appearance of episodes (A, B and C). Muscle contraction and stiffness started from the hind limbs (A) and involved in the forelimbs (B). The patient was conscious and responsive to the owner (B). Arching of the lumbar spine was detected (C).

On physical examination, the patient’s body condition score (BCS) was 5 out of 9. No remarkable signs were observed. The results of a complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry and electrolyte analysis were within normal ranges, and the patient’s pre- and postprandial bile acid concentrations were normal (Table 1). The patient was normal in a neurologic examination, and no remarkable changes were found in abdominal radiographic and ultrasonographic examinations. To rule out other diseases, such as brain disease and portal vasculature abnormality, angiographic computed tomography (CT) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed. No evidence of portosystemic shunt or brain disease was observed (Figs. 2 and 3). After the tests were conducted, the patient’s condition was suspected to be CECS, and as a trial therapy, Science Diet k/d (Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Topeka, KS, U.S.A.) was prescribed. The clinical signs were dramatically reduced after diet therapy, and no recurrence has been observed until the present time (13 months). After the trial diet therapy, we diagnosed the patient with CECS.

Table 1. Laboratory liver panel analysis of the dog with CECS.

| Reference range | Initial examination | Recheck | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALP (U/l) | 20–150 | 46 | 42 |

| GGT (U/l) | 0–7 | 7 | 6 |

| ALT (U/l) | 10–118 | 45 | 83 |

| TBIL (mg/dl) | 0.1–0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Bile acid (µmol/l) | 0–25 | ||

| Pre prandial | 15 | 16 | |

| Post prandial | 10 | 5 | |

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase, GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, ALT: Alanine transaminase, TBIL: Total bilirubin.

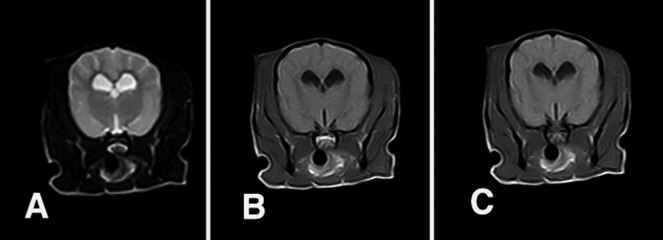

Fig. 2.

T2-weighted (A), T1-weighted (B) and T1-weighted transverse post-contrast images (C) of the brain. There were no specific findings from the MRI examination.

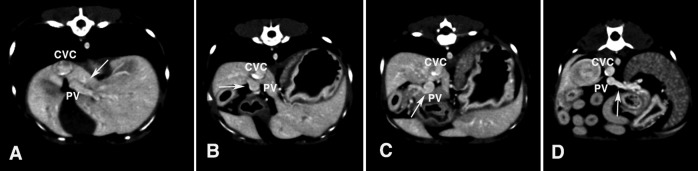

Fig. 3.

Post-contrast computed tomographic images of the portal vein. (A) Left portal branch (arrow) of the portal vein. (B) Short right branch (arrow) of the portal vein. (C) Gastroduodenal tributary (arrow) of the portal vein. (D) Splenic tributary (arrow) of the portal vein. There are no specific findings for the portal vasculature. CVC, caudal vena cava; PV, portal vein.

A paroxysmal cramping or hypertonicity syndrome in Border terriers has recently been recognized as a condition known as canine epileptoid cramping syndrome (CECS, also known as Spike’s disease) [1, 3, 13]. Paroxysmal dyskinesias are a group of movement disorders in human medicine [1]. This group is characterized by involuntary movement and sudden occurrence with normal motor function and no neurologic deficits between episodes [1]. CECS or Spike’s disease in Border terrier has been reported over the last 10 years and suspected to be a breed-related paroxysmal dyskinesia [1]. Signs shown by affected individuals are very diverse. Gait abnormalities ranging from ataxia to inability to stand result from muscle hypertonicity that may be apparent in the mounding of muscles over the back and limb rigidity [3, 13]. Affected dogs may fall over and remain recumbent. In severe cases, cramping of the intestinal muscles may occur and can be detected based on audible borborygmi and abdominal pain [3]. All characteristics, including gait, are normal between episodes. Unlike during seizure, dogs are conscious and responsive to owners [1, 13]. The age of onset is usually 2 to 6 years, but is sometimes as early as 4 months of age [1, 13]. In most cases, an episode lasts from a few sec to several min and is self-limiting, but an episode could last significantly longer [1, 13]. Some dogs may experience only one or 2 episodes during their lives, while others have episodes throughout their lives with the frequency of episodes varying from daily to monthly [3]. This variety of patterns of frequency suggest that CECS waxes and wanes [1]. Similar to hypertonicity disorders, CECS can be controlled with diazepam, but diet therapy with a low-protein food, such as Science Diet k/d or a hypoallergenic diet, can be an effective treatment option [13]. As a possible cause of CECS, metabolic disease and hepatic microvascular dysplasia have been suspected, but it is mainly thought to be hereditary [13]. Therefore, genetic research to identify a marker for CECS is underway [3]. In a previous study, a canine BCAN microdeletion was found as a genetic problem related to episodic falling syndrome (EFS), which is a canine paroxysmal hypertonicity disorder found in Cavalier King Charles spaniels [4]. In the case of metabolic myopathies, electrically silent muscle cramps may occur with strenuous or ischemic exercise due to a lack of glycolysis or glycogenolysis [13]. Physiological cramps are a common condition in normal individuals after voluntary contractions or during sleep or rest and can be relieved by passive muscle stretching and local massage [12, 13]. In fact, some affected patients show elevated bile acid levels, which indicates the possibility of hepatic microvascular dysplasia as an underlying disease [13]. Although no specific findings were observed on computed tomographic images of the portal vasculature in this case, liver biopsy or scientigraphy will be needed to rule out microvascular dysplasia completely. However, in the current case, the patient showed normal liver panels including bile acid levels, so a liver biopsy was not performed. In this case, partial seizure was suspected based on the clinical signs at the first physical examination. However, the features of seizure activity were not typical. According to Black et al., paroxysmal dyskinesia is distinguished from partial seizure by movement observation, duration of episode, absence of urination or defecation and hypersalivation [1]. In this case, the patient did not show urination, defecation or hypersalivation. In the case of seizure activity, autonomic signs could be observed [1]. The patient was conscious during episodes and did not show postictal behavior. In the case of partial seizure, seizure activity could be recorded on ictal EEG, and this would aid in distinguishing between seizure and cramping [1]. However, we could not perform an EEG examination in this case due to a lack of equipment. In this case, we could not find any evidence of pre-ictal, ictal or post-ictal phase activity, such as barking, hypersalivation and restless. The episodes started without any warning. After the episodes, the patient was totally normal. During the episodes, the patient’s muscle tone was hypertonic with lumbar and limb muscle contractions and showed sustained and involuntary contractions with bending of the left elbow and knee joint. The general features of the episodes were similar to those of cramping syndrome. Because animals cannot complain of painful muscle cramps, we cannot know whether the episodes were accompanied by pain, which makes it difficult for veterinary medicine clinicians to recognize cramps. Accompanying clinical signs, such as anorexia after episodes and increased abdominal borborygmi sounds, may imply that intestinal muscle cramping occurred.

Channelopathies are ion-channel abnormalities in human medicine, and periodic paralyses were found on distal exercise muscles asymmetrically [5]. Hypokalemic periodic paralysis, which is one of the channelopathies, was brought on by a period of exercise followed by rest or carbohydrate loading, and a carbohydrate meal on the previous evening could make it worse in the early morning on the next day [5]. Therefore, a change in diet change can be helpful in management of channelopathies [5]. The periodic paralyses and change in diet are similar to those in our case, but channelopathies are accompanied by muscle weakness. Our patient did not show muscle weakness, but instead showed muscle rigidity. Regarding diet therapy, we changed the patient’s diet to Science Diet k/d (Hill’s Pet Nutrition), which is a protein-restricted but not carbohydrate-restricted diet, and there was no history of feeding the patient a carbohydrate enriched diet, such as one containing sweet potato or rice. In the present case, the patient was referred with the chief complaint of partial seizure-like cramping, and other diseases, including metabolic and brain diseases, were ruled out by neurologic examination, blood panel, MRI and CT results. We presumed the possibility of CECS, and Science Diet k/d was prescribed as a trial therapy. The exact mechanism of diet therapy in CECS has not been found, but the clinical signs in the present case dramatically disappeared after applying the diet therapy, so we diagnosed the patient as having CECS. This is the first case report of CECS in a Yorkshire terrier.

In conclusion, muscle hypertonicity syndromes, such as CECS, have a similar spectrum of clinical signs to that of partial seizure, and it is difficult to determine whether they are accompanied by pain. These difficulties prevent the clinician from recognizing cramping syndrome in veterinary medicine. Therefore, clinicians must consider the possibility of cramping syndrome in cases presenting with apparent partial seizure episodes, and a trial diet therapy could be the initial treatment option before administration of antiepileptic drugs. Furthermore, we found that CECS can occur in Yorkshire terriers. Therefore, further genetic studies including other breeds are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Chungnam National University in the form of research funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black V., Garosi L., Lowrie M., Harvey R. J., Gale J.2014. Phenotypic characterization of canine epileptoid cramping syndrome in the Border terrier. J. Small Anim. Pract. 55: 102–107. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemmons R. M., Peters R. I., Meyers K. M.1980. Scotty cramp: a review of cause, characteristics, diagnosis and treatment. Compend. Contin. Educ. Vet. 2: 285–390 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garosi L., Harvey R. J.2012. Scottie cramp and canine epileptoid cramping syndrome in Border terriers. Vet. Rec. 170: 186–187. doi: 10.1136/vr.e1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill J. L., Tsai K. L., Krey C., Noorai R. E., Vanbellinghen J. F., Garosi L. S., Shelton G. D., Clark L. A., Harvey R. J.2012. A canine BCAN microdeletion associated with episodic falling syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 45: 130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graves T. D., Hanna M. G.2005. Neurological channelopathies. Postgrad. Med. J. 81: 20–32. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.022012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawke F., Chuter V., Burns J.2013. Factors associated with night-time calf muscle cramps: a case-control study. Muscle Nerve 47: 339–343. doi: 10.1002/mus.23531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers K. M., Padgett G. A., Dickson W. M.1970. The genetic basis of a kinetic disorder of Scottish terrier dogs. J. Hered. 61: 189–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller T. M., Layzer R. B.2005. Muscle cramps. Muscle Nerve 32: 431–442. doi: 10.1002/mus.20341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minetto M. A., Holobar A., Botter A., Farina D.2013. Origin and development of muscle cramps. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 41: 3–10. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3182724817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley J. D., Antony S. J.1995. Leg cramps: differential diagnosis and management. Am. Fam. Physician 52: 1794–1798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts D. D., Hitt M. E.1986. Methionine as a possible inducer of Scotty cramp. Canine Pract. 13: 29–31 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito M., Olby N. J., Obledo L., Gookin J. L.2002. Muscle cramps in two standard poodles with hypoadrenocorticism. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 38: 437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelton G. D.2004. Muscle pain, cramps and hypertonicity. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 34: 1483–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2004.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanhaesebrouck A. E., Bhatti S. F., Franklin R. J., Van Ham L.2013. Myokymia and neuromyotonia in veterinary medicine: a comparison with peripheral nerve hyperexcitability syndrome in humans. Vet. J. 197: 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods C. B.1977. Hyperkinetic episodes in two Dalmatian dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 13: 255–257 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright J. A., Brownile S. E., Smyth J. B., Jones D. G., Wotton P.1986. Muscle hypertonicity in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel-myopathic features. Vet. Rec. 118: 511–512. doi: 10.1136/vr.118.18.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]