ABSTRACT

Astroviruses and kobuviruses are frequently found in mammalian feces, including that of humans. The present study examined fecal samples from 91 Korean dogs suffering from diarrhea. Canine astroviruses (CAstVs) and canine kobuviruses (CKoVs) were identified in 2 (2.1%) and 46 (50.6%) dogs, respectively. Nucleotide sequence analysis coupled with phylogenetic analysis using the neighbor-joining method showed that CAstVs clustered into four genetically diverse groups. Two Korean CAstVs belonged to group 2 alongside strains isolated in Italy and France. Twelve of the Korean CKoVs belonged to a single clade, along with strain UK003 identified in the UK and six CKoVs identified in the USA. Thus, the results suggest that the Korean strain of CAstV is closely related to strains isolated in Europe. Surely, CKoV in South Korea could identify the circulation among dogs population.

Keywords: canine astrovirus, canine kobuvirus, phylogeny, South Korea

Astroviruses (AstVs) are small non-enveloped RNA viruses that were first identified in 1975 in samples taken from children suffering from diarrhea [1, 18]. In 1980, astrovirus-like particles (subsequently named canine astrovirus (CAstV)) were observed electron microscopically in diarrhea samples taken from beagle puppies [29] and in the feces of asymptomatic dogs [14]. Since then, there have been reports of CAstV in dogs in the U.S.A., Germany, Austria, Italy, China, France and Brazil [4, 7, 14, 27,28,29, 31]; however, little is known about the clinical symptoms associated with CAstV infection.

Human Aichi virus (AiV) is a prototype kobuvirus, which was first identified in 1989 as the cause of an outbreak of human gastroenteritis in Aichi Prefecture, Japan [30]. Kobuviruses, which belong to the family Picornaviridae, are non-enveloped viruses that contain a single-stranded RNA genome; these viruses have been identified in sheep, goats, wild boar, rodents, dogs and cats [2, 3, 10, 12, 22, 24, 25]. In 2011, canine kobuvirus (CKoV) was identified in dogs in the U.S.A. [10, 13], showing for the first time that domestic pets can be infected by members of this genus.

Previous studies have reported a significant association between the onset and severity of astrovirus infections and age in young puppies (5–7 weeks old) [7], mink (3 weeks old) [6] and children (under 2 years old) [20].

Sequence analysis of the complete CKoV genome revealed that the virus shows greatest sequence similarity to a recently identified murine kobuvirus, strain M-5/USA/2010 (84.0% identical at the amino acid (aa) level) [22] and to human AiVs (80.0% identical at the aa level) [21]. Few studies have examined astroviruses and kobuviruses in dogs, and little information is available regarding their prevalence, genetic diversity and pathogenicity.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were to examine the prevalence, genetic diversity and geographical relationships between CAstVs and CKoVs in Korean dogs.

Between February and December 2010, samples of dog feces (n=91) were collected from two animal shelters and three animal hospitals located in Seoul and the Gyeonggi region of South Korea. All dogs were aged between 1 and 24 months and were suffering from diarrhea. Infection with canine parvovirus (CPV) and canine coronavirus (CCoV) was diagnosed by PCR using previously described primer sets [9, 23].

Viral RNA was extracted with TRIzol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA. U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR and random hexamers (Invitrogen; Cat. No. 18080-051). The primers used to amplify part of the CAstV ORF2 gene were modified from those described previously [31]: forward primer, 5′-TGGCTGGACCACGTGAA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-TCACGTTTAGGTCGAGA-3′. The primers used to amplify a partial sequence from CKoV RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) were also modified from those previously published [10]: forward primer, 5′-CTCCCCTCAGCTGCCTTCTC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GAGGATCTGAAATTTGGAAG-3′. The PCR conditions used to amplify CAstV were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 53°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR conditions used to amplify CKoV were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 52°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The resulting PCR products (196 bp for CAstV and 252 bp for CKoV) were separated on a 1% agarose gel, isolated and then cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.; Cat. No. A1360). The cloned fragments were sequenced on an ABI Prism 3730 × i DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) at the Macrogen company (Seoul, Korea) using T7 and SP6 universal primers.

Of the 91 samples tested, CAstV, CKoV, CPV and CCoV were identified in 2 (2.2%), 46 (50.5%), 49 (53.8%) and 61 (67.0%), respectively. The partial CAstV ORF2 nucleotide sequences from two Korean strains and from 13 strains identified in other countries were aligned using the CLUSTAL X [26] and BIOEDIT programs [8]. Based on these sequence alignments, 15 CAstV strains were divided into four groups; the level of sequence similarity between the four groups was<80% (Table 1). The level of sequence similarity within groups, however, was higher. The SH8 strain (China), the 4255-239 strain (France) and strains 1068, 915, 905 and 1093 (Brazil) belonged to group 1, and all showed a high level of sequence similarity at the nucleotide level (91.3–93.4%). Seven strains (8/05, 6/05, 3/05, 4255–299, 4255–93, CAstV-K47 and CAstV-K48) belonged to group 2 and also showed high sequence homology (94.9–99.5%) at the nucleotide level (data not shown). The sequence homology between CAstVs and AstVs isolated from other animal species (mink, pig, rabbit, mouse, duck and human) was low (45.9–63.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Nucleotide sequence similarities among the partial ORF2 gene sequences derived from different astrovirus strains.

| Species | Dog |

Mink | Pig | Rabbit | Mouse | Duck | Human | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | 1068 | CAstV-K47 | GI.E | 4255-280 | Astrovirus | Tokushima 83-74 | TN rabbit 10-2208 | STL 1 | C-NGB | ITA/2002/PA65R/type2c | |

| Dog | 1068 | - | 76.0 | 73.5 | 79.1 | 57.7 | 60.2 | 63.3 | 50.0 | 48.5 | 48.5 |

| CAstV-K47 | 76.0 | - | 75.0 | 78.1 | 60.2 | 63.3 | 61.7 | 51.0 | 47.4 | 50.0 | |

| GI.E | 73.5 | 75.0 | - | 77.0 | 58.7 | 60.7 | 60.2 | 53.6 | 48.9 | 48.9 | |

| 4255-280 | 79.1 | 78.1 | 77.0 | - | 61.7 | 62.8 | 58.7 | 56.1 | 45.9 | 46.4 | |

A previous study showed that AstVs circulating in French kennels showed a higher level of genetic diversity (nucleotide sequence similarity ranging from 72.5–99.5%) than those identified in puppies presenting at a clinic in China (nucleotide sequence similarity ranging from 96.7–99.8%) [31]. The discrepancy between these levels of nucleotide sequence similarity may explain the genetic diversity of the French CAstVs examined in the present study; the French CAstVs belonged to groups 1, 2 and 4, while all of the Chinese CAstVs belonged to group 1.

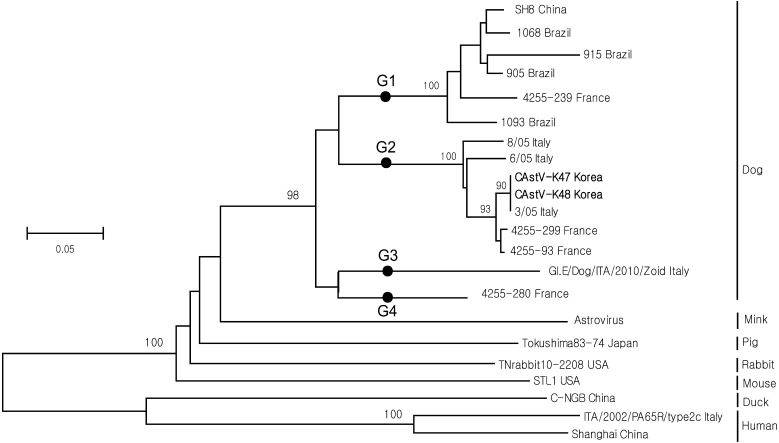

We next constructed a phylogenetic tree for the partial CAstV ORF2 gene using the Mega 4.1 program [11]. As shown in Fig. 1, the sequences clustered into four genetically diverse groups. Six CAstV strains belonged to group 1, seven strains belonged to group 2, and one strain (GI.E/Dog/ITA/2010/Zoid) from Italy and one strain (4255-280) from France belonged to groups 3 and 4, respectively. A previous study suggested that a closer examination of the phylogenetic tree revealed that CAstV sequences appeared to cluster according to their place of origin (e.g., country or kennel) [7]. Another study showed that CAstVs are both genetically and antigenically heterogeneous, showing levels of variation similar to those in human GI.A AstV types 1 to 8 [16, 19]. The Korean CAstVs belonging to genotype G2 may be more related to viruses isolated from Europe than to viruses isolated from China; however, further studies are needed to confirm this.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships between canine astroviruses (CAstVs) and astroviruses from other animal species (based on partial ORF2 sequences). The tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method within Mega 4.1 software using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values>70% are shown at the branch points. Korean CAstVs are marked in bold.

Recent molecular studies indicate that CAstVs are widespread among the canine population, occurring either as single infections or as co-infections with other viral pathogens [17]. This suggests that CAstVs may be enteric pathogens in young dogs. CAstVs are associated with outbreaks of enteritis in puppies infected with CAstV alone or co-infected with CAstV and either CCoV or CPV [15]. Two Korean CAstVs detected in samples from shelter dogs were found in conjunction with CCoV and CKoV; however, the clinical characteristics of enteric infection by CAstVs are unknown.

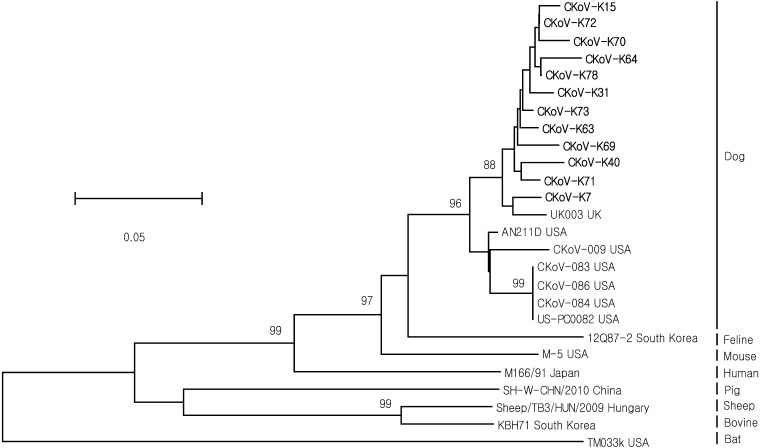

Of the 46 Korean CKoV strains examined, 34 had the same partial RdRp nucleotide sequence as 12 strains (Fig. 2). Twelve Korean CKoV strains showed 95.2–96.8% similarity at the nucleotide level. CKoV-K7 showed the closest relationships with UK003 (97.2%) from the U.K. and with CKoV-009 (92.8%) from the U.S.A. (Table 2). In addition, CKoVs and kobuviruses identified in three animal species (mouse, cat and human) showed a high level of sequence similarity (80.9–87.6%) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the partial RdRp region from different kobuvirus strains. The bootstrap percentages (supported by at least 70% of the 1,000 replicates) are shown above the nodes. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Canine kobuvirus strains identified in South Korea are shown in bold.

Table 2. Nucleotide sequence similarities among the partial RdRp gene sequences derived from different kobuvirus strains.

| Species | Dog |

Cat | Mouse | Human | Cow | Sheep | Pig | Bat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | UK003 | 009 | 12Q87-2 | M-5 | M166/91 | KBH71 | TB3 | SH-W | TM003k | |

| Dog | K7 | 97.2 | 94.4 | 87.6 | 87.6 | 82.5 | 71.0 | 69.4 | 71.4 | 55.9 |

| K15 | 96.0 | 93.2 | 87.6 | 87.3 | 81.3 | 70.2 | 70.2 | 71.4 | 69.8 | |

| K31 | 96.0 | 92.8 | 86.5 | 87.6 | 80.9 | 70.6 | 71.0 | 71.4 | 59.5 | |

| K40 | 96.0 | 94.4 | 87.3 | 86.9 | 82.1 | 69.4 | 69.4 | 71.8 | 55.5 | |

| K63 | 96.4 | 92.8 | 88.0 | 87.6 | 81.7 | 70.6 | 69.4 | 72.2 | 55.1 | |

| K64 | 95.6 | 92.8 | 87.3 | 86.9 | 80.9 | 69.8 | 69.0 | 71.8 | 55.1 | |

| K69 | 96.0 | 93.6 | 86.5 | 86.5 | 81.3 | 69.4 | 69.4 | 70.6 | 55.9 | |

| K70 | 96.4 | 93.6 | 86.9 | 86.9 | 82.1 | 69.8 | 70.6 | 72.6 | 55.5 | |

| K71 | 96.8 | 93.6 | 86.1 | 87.3 | 81.3 | 70.6 | 70.6 | 72.2 | 55.9 | |

| K72 | 96.8 | 94.0 | 87.6 | 87.3 | 82.1 | 70.2 | 70.2 | 72.2 | 55.5 | |

| K73 | 96.4 | 93.2 | 86.5 | 86.9 | 80.9 | 71.0 | 70.2 | 71.0 | 55.5 | |

| K78 | 96.4 | 93.6 | 86.5 | 86.9 | 80.9 | 71.0 | 69.8 | 71.8 | 55.1 | |

Based on sequence analysis of the complete genome, CKoV showed the closest genetic relationship with a recently identified mouse kobuvirus, M-5/USA/2010 (84.0% identical at the aa level) [22], and with a human AiV (80.0% identical at the aa level) [5].

The phylogenetic tree derived from partial RdRp gene sequences from various animal species showed that CKoVs clustered into a single clade, which contained 12 CKoVs from Korea, one CKoV (UK003) from the U.K., and six CKoVs from the U.S.A. CKoVs were also closely related to a feline kobuvirus (12Q87-2) and a murine kobuvirus (M-5). Previous studies have shown that CKoVs are not geographically restricted to the North American continent on which they were first identified [10, 13]. The present study did not find evidence of genetic diversity between viruses identified in the U.S.A., U.K. and Korea, which are representative of three different continents.

Of the CKoV-positive dogs, 2.34% (6/256) presented with diarrhea and were either infected by CKoV alone or were co-infected with CCoV and/or CPV-2 [5]. Although it is difficult to directly associate CKoV infection with clinical signs of enteric disease [13], we did find that some Korean dogs were co-infected with CKoVs and other viral pathogens that are known to cause enteric disease. For example, 18 dogs were infected with CCoV+CKoV, 10 with CPV+CKoV, 14 with CCoV+CPV+CKoV and 2 with CCoV+CAstV+CKoV (data not shown). Infection by CKoVs was more prevalent in samples from shelters than in samples from animal hospitals (Table 3).

Table 3. Association between sample collection site and prevalence of infection by Canine Kobuvirus.

| Collection place of fecal samples | Total | Canine Kobuvirus |

ORa) | 95% CIb) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| Shelter | 38 | 25 | 13 | 2.99 | 1.23–6.98 | 0.02 |

| Animal Hospital | 53 | 21 | 32 | |||

Data were evaluated using Fishers exact test. P values<0.05 were considered significant. a) OR, Odds ratio; b) CI, Confidential interval.

In conclusion, of the four genetically diverse groups identified by phylogenetic analysis, Korean CAstVs were classified into group 2 and were closely related to strains identified in Europe. CKoVs do not yet show evidence of genetic diversity, and Korean CKoVs could identify the circulation with viral pathogens that associated to enteric diseases among dogs population.

NUCLEOTIDE SQUENCE ACCESSION NUMBERS

The nucleotide sequences of CAstV and CKoV isolated from Korean dogs were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: KF663753 to KF663754 for the partial ORF2b region sequences derived from CAstV; and KF663755 to KF663766 for the partial RdRp region sequences derived from CKoV.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (Project Code No. N-AD20-2010-19-01) from the Animal, Plant & Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency (QIA), Ministry of Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Republic of Korea, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleton H., Higgins P. G.1975. Letter: viruses and gastroenteritis in infants. Lancet 1: 1297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92581-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry A. F., Ribeiro J., Alfieri A. F., van der Poel W. H., Alfieri A. A.2011. First detection of kobuvirus in farm animals in Brazil and the Netherlands. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11: 1811–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmona-Vicente N., Buesa J., Brown P. A., Merga J. Y., Darby A. C., Stavisky J., Sadler L., Gaskell R. M., Dawson S., Radford A. D.2013. Phylogeny and prevalence of kobuviruses in dogs and cats in the UK. Vet. Microbiol. 164: 246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro T. X., Cubel Garcia R. C., Costa E. M., Leal R. M., Xavier M. daP. T., Leite J. P.2013. Molecular characterization of calicivirus and astrovirus in puppies with enterits. Vet. Rec. 172: 557. doi: 10.1136/vr.101566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Martino B., Di Felice E., Ceci C., Di Profio F., Marsilio F.2013. Canine kobuviruses in diarrhoeic dogs in Italy. Vet. Microbiol. 166: 246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund L., Chriel M., Dietz H. H., Hedlund K. O.2002. Astrovirus epidemiologically linked to pre-weaning diarrhoea in mink. Vet. Microbiol. 85: 1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grellet A., De Battisti C., Feugier A., Pantile M., Gradjean D., Cattoli G.2012. Prevalence and risk factors of astrovirus infection in puppies from French breeding kennels. Vet. Microbiol. 157: 214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall T. A.1999. BIOEDIT: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41: 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda Y., Mochizuki M., Naito R., Nakamura K., Miyazawa T., Mikami T., Takahashi E.2000. Predominance of canine parvovirus (CPV) in unvaccinated cat populations and emergence of new antigenic types of CPVs in cats. Virology 278: 13–19. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapoor A., Simmonds P., Dubovi E. J., Qaisar N., Henriquez J. A., Medina J., Shields S., Lipkin W. I., Kapoor A., Simmonds P., Dubovi E. J., Qaisar N., Henriquez J. A., Medina J., Shields S., Lipkin W. I.2011. Characterization of a canine homology of human Aichivirus. J. Virol. 85: 11520–11525. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05317-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S., Nei M., Dudley J., Tamura K.2008. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 9: 299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M. H., Jeoung H. Y., Lim J. Y., Song J. A., Song D. S., An D. J.2012. Kobuvirus in South Korean black goats. Virus Genes 45: 186–189. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0745-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li L., Pesavento P. A., Shan T., Leutenegger C. M., Wang C., Delwart E.2011. Viruses in diarrhoeic dogs include novel kobuviruses and sapoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 92: 2534–2541. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034611-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall J. A., Healey D. S., Studdert M. J., Scott P. C., Kennett M. L., Ward B. K., Gust I. D.1984. Viruses and virus-like particles in the faeces of dogs with and without diarrhoea. Aust. Vet. J. 61: 33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1984.tb07186.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martella V., Lorusso E., Decaro N., Elia G., Radogna A., D’Abramo M., Desario C., Cavalli A., Corrente M., Camero M., Germinario C. A., Bányai K., Di Martino B., Marsilio F., Carmichael L. E., Buonavoglia C.2008. Detection and molecular characterization of a canine norovirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14: 1306–1308. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martella V., Moschidou P., Catella C., Larocca V., Pinto P., Losurdo M., Corrente M., Lorusso E., Bànyai K., Decaro N., Lavazza A., Buonavoglia C.2012. Enteric disease in dogs naturally infected by a novel canine astrovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50: 1066–1069. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05018-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martella V., Moschidou P., Lorusso E., Mari V., Camero M., Bellacicco A., Losurdo M., Pinto P., Desario C., Bányai K., Elia G., Decaro N., Buonavoglia C.2011. Detection and characterization of canine astroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 92: 1880–1887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsui S. M., Greenberg H. B.1996. Astroviruses (Davis, P. M. H. and Kinipe, M. eds.), Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Méndez-Toss M., Romero-Guido P., Munguía M. E., Méndez E., Arias C. F.2000. Molecular analysis of a serotype 8 human astrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 81: 2891–2897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser L. A., Schultz-Cherry S.2005. Pathogenesis of astrovirus infection. Viral Immunol. 18: 4–10. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh D. Y., Silva P. A., Hauroeder B., Diedrich S., Cardoso D. D., Schreier E.2006. Molecular characterization of the first Aichi viruses isolated in Europe and in South America. Arch. Virol. 151: 1199–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan T. G., Kapusinszky B., Wang C., Rose P. K., Lipton H. L., Delwart E. L.2011. The fecal viral flora of wild rodents. PLoS Pathog. 7: e1002218. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pratelli A.2006. Genetic evolution of canine coronavirus and recent advances in prophylaxis. Vet. Res. 37: 191–200. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuter G., Boros A., Pankovics P., Egyed L.2010. Kobuvirus in domestic sheep, Hungary. Emerging Infect. Dis. 16: 869–870. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuter G., Nemes C., Boros A., Kapusinszky B., Delwart E., Pankovics P.2013. Porcine kobuvirus in wild boars (Sus scrofa). Arch. Virol. 158: 281–282. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1456-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G.1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toffan A., Jonassen C. M., De Battisti C., Schiviavon E., Kofstad T., Capua I., Cattoli G.2009. Genetic characterization of a new astrovirus detected in dogs suffering from diarrhoea. Vet. Microbiol. 139: 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vieler E., Herbst W.1995. Electron microscopic demonstration of viruses in feces of dogs with diarrhea. Tierarztl. Prax. 23: 66–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams F. P., Jr1980. Astrovirus-like, coronavirus-like, and parvovirus-like particles detected in the diarrheal stools of beagle pups. Arch. Virol. 66: 215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01314735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita T., Kobayashi S., Sakae K., Nakata S., Chiba S., Ishihara Y., Isomura S.1991. Isolation of cytopathic small round viruses with BS-C-1 cells from patients with gastroenteritis. J. Infect. Dis. 164: 954–957. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu A. L., Zhao W., Yin H., Shan T. L., Zhu C. X., Yang X., Hua X. G., Cui L.2011. Isolation and characterization of canine astrovirus in China. Arch. Virol. 156: 1671–1675. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1022-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]