Abstract

Background and Aims:

The potentiating effect of short acting lipophilic opioid fentanyl and a more selective α2 agonist dexmedetomidine is used to reduce the dose requirement of bupivacaine and its adverse effects and also to prolong analgesia. In this study, we aimed to find out whether quality of anaesthesia is better with low dose bupivacaine and fentanyl or with low dose bupivacaine and dexmedetomidine.

Methods:

This prospective randomised double-blinded study was carried out in a tertiary health care centre on 150 patients by randomly allocating them into two groups using a computer generated randomisation table. Group F (n = 75) received bupivacaine 0.5% heavy (0.8 ml)+fentanyl 25 μg (0.5 ml) + normal saline 0.3 ml and Group D (n = 75) received bupivacaine 0.5% heavy (0.8 ml) + dexmedetomidine 5 μg (0.05 ml) + normal saline 0.75 ml, aiming for a final concentration of 0.25% of bupivacaine (1.6 ml), administered intrathecally. Time to reach sensory blockade to T10 segment, peak sensory block level (PSBL), time to reach peak block, time to two segment regression (TTSR), the degree of motor block, side-effects, and the perioperative analgesic requirements were assessed.

Results:

There were no significant differences between the groups in the time to reach T10 segment block (P > 0.05) and TTSR (P > 0.05);time to reach PSBL (P < 0.05) and modified Bromage scales (P < 0.05) were significant. PSBL (P = 0.000) and time to first analgesic request (P = 0.000) were highly significant. All patients were haemodynamically stable and no significant difference in adverse effects was observed.

Conclusion:

Both groups provided adequate anaesthesia for all lower abdominal surgeries with haemodynamic stability. Dexmedetomidine is superior to fentanyl since it facilitates the spread of the block and offers longer post-operative analgesic duration.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, low dose bupivacaine, opioids, spinal anaesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Spinal anaesthesia is a simple technique with rapid onset of action. However, a commonly used anaesthetic like lidocaine has neurotoxic effects and this has been been largely replaced by other agents such as bupivacaine. The routine doses of bupivacaine are associated with prolonged and intense sensory and motor block and significant sympathetic block, which may not be desirable in some patients. Low dose diluted bupivacaine limits the distribution of spinal block and yield a comparably rapid recovery, but may not provide an adequate level of sensory block.[1] The potentiating effect of short acting lipophilic opioid fentanyl and a more selective α2 agonist dexmedetomidine is used to reduce the dose requirement of bupivacaine and its adverse effects. These spinal adjuncts are used not only to reduce side-effects of local anaesthetics, but also to prolong analgesia.

For lipophilic opioids like fentanyl and sufentanil, the risk of respiratory depression is predominantly limited to the first 2 h after intrathecal injection.[2] Since fentanyl is more lipid soluble than morphine, the risk of delayed respiratory depression due to rostral spread of intraspinally administered narcotic to respiratory centres is greatly reduced.[3]

Intrathecal α2 receptor agonists have antinociceptive action for both somatic and visceral pain. Dexmedetomidine shows more specificity towards α2 receptor (α2/α1 1600:1) compared with clonidine (α2 /α1 200:1).[4] Several studies have shown that α2 receptor agonists when administered intrathecally will enhance the analgesia provided by subtherapeutic doses of local anaesthetics like bupivacaine due to synergistic effects with minimal haemodynamic effects.[4,5,6] We aimed to find out whether quality of anaesthesia is better with low dose bupivacaine and fentanyl or with low dose bupivacaine and dexmedetomidine.

METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Ethical Committee approval, this prospective randomised double-blinded study was carried out in a tertiary health care centre on 150 patients of both sex aged between 18 and 60 years, belonging to American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Grade I and II undergoing elective lower abdominal surgeries (viz. urological and general surgical procedures) under spinal anaesthesia. Patients with a history of spine surgery, infection at the injection site, coagulopathy, hypovolemia, increased intracranial pressure, indeterminate neurologic disease, spinal deformities, communication problems, known hypersensitivity to local anaesthetics, opioids or dexmedetomidine were excluded from the study.

Sample size was calculated based on previous study,[1] using the standard deviation of time to first analgesic request (TFAR). To detect a mean difference of 2 h between the groups in terms of TFAR with α = 5% and 1− β = 90%, 74 patients per study group were needed. Hence, 75 patients were included in each group.

A randomisation list was computer generated and patients were randomly allocated to two groups, (Group F – fentanyl group and Group D – dexmedetomidine group) 75 patients in each group and informed consent was obtained. Patients received no premedication and no preloading was undertaken. The age, sex, weight and height of the patients were recorded. Vital parameters were monitored using electrocardiogram, non-invasive arterial pressure, and peripheral oxygen saturation. Intrathecal drugs were prepared by an anaesthesiologist not involved in the study and were administered by another anaesthesiologist who was blinded and performed spinal anaesthesia. Volume of the drug, size of the syringe and colour of the drug of interest were similar in both groups.

Spinal anaesthesia was performed in all patients in the lateral decubitus position with operating table tilted 5-10° in Trendelenberg position. Trendelenberg position was maintained throughout the surgery. Under strict aseptic precautions, using 25G Quincke needle mid-line spinal puncture was performed at L2-L3 level.

In Group F, injection bupivacaine 0.5% (0.8 ml) + fentanyl 0.5 ml (25 μg) + normal saline 0.3 ml, (for a final concentration of 0.25% and volume of 1.6 ml of bupivacaine) was administered intrathecally. In Group D, dexmedetomidine was first diluted in normal saline to obtain a dose of 5 μg in 0.5 ml. Then, injection bupivacaine 0.5% (0.8 ml) + dexmedetomidine 0.5 ml (5 μg) + normal saline 0.3 ml (for a final concentration of 0.25% and volume of 1.6 ml of bupivacaine) was administered intrathecally. Drug was administered over 10 seconds (s) using 2 cc syringes with cephalad orientation of the spinal needle bevel. The patients were turned supine immediately after the injection of the drug. The completion of the injection was taken as zero time of the induction of anaesthesia.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR) were recorded every 5 min up to 15 min and then every 15 min up to 90 min irrespective of the duration of surgery. Hypotension, defined as SBP <90 mm Hg or >30% fall from the baseline value was treated by injection mephentermine 3 mg intravenous (i.v) and i.v crystalloids. Bradycardia was defined as HR <60 beats/min or >30% decrease from the baseline value and was treated with i.v atropine 0.3 mg increments. We assessed time to reach T10 block level, peak sensory block level (PSBL), time to reach peak block level, time to two segment regression (TTSR) and degree of motor blockade.

Sensory block level which was defined as the loss of pain sensation to pin prick test in the midclavicular line, was measured every 1 min until it reached T10 level, and the surgeons were asked to start and then every 2 min until it reached PSBL. Peak block level was defined as the level that remained same during four consecutive tests. TTSR was noted by checking every 10 min after the peak block level was reached. The degree of motor blockade at the time of peak sensory block was scored using a modified Bromage scale (MBS)[1] - (1) Complete motor block, (2) Almost complete motor block, patient is able to move only feet, (3) Partial motor block, patient is able to move the knees, (4) Detectable weakness of hip flexion, patient is able to raise the leg but is unable to keep it raised, (5) No detectable weakness of hip flexion, patient is able to keep the leg raised for 10s at least, (6) No weakness at all). The quality of anaesthesia was assessed as excellent (no discomfort or pain), good (mild pain or discomfort and no need for additional analgesics), fair (pain that required analgesics), poor (severe pain that required analgesics). Tramadol 100 mg IV supplemented by intramuscular diclofenac 75 mg were administered on request as rescue analgesic. Supplemental analgesic use, TFAR (in hours) post-operatively and side-effects such as hypotension, bradycardia, pruritus, vomiting, respiratory depression were also monitored. Pruritus was managed with i.v chlorpheniramine maleate.

The primary outcome of the study was to assess which group produced a longer duration of analgesia measured in terms of the first request for analgesia post-operatively. The secondary outcome was to compare the two groups in terms of time of onset of analgesia (T10 block level assessed by pin prick), peak sensory level, and time to reach peak block, TTSR, degree of motor blockade and haemodynamic profile of the two groups.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 16.0 software, Chicago, SPSS Inc. Student's t-test was used to analyse age, weight, height, pulse rate, SBP, DBP, time to T10 block, time to PSBL, TTSR, and TFAR. Chi-square was used to analyse sex, ASA, PSBL, maximum motor blockade and side-effects. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

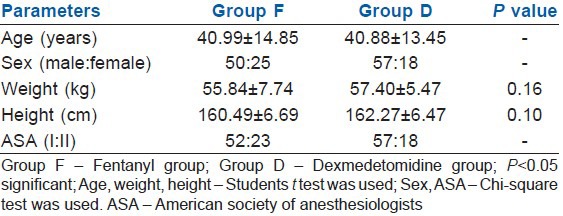

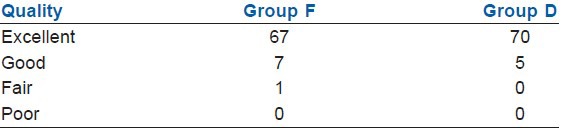

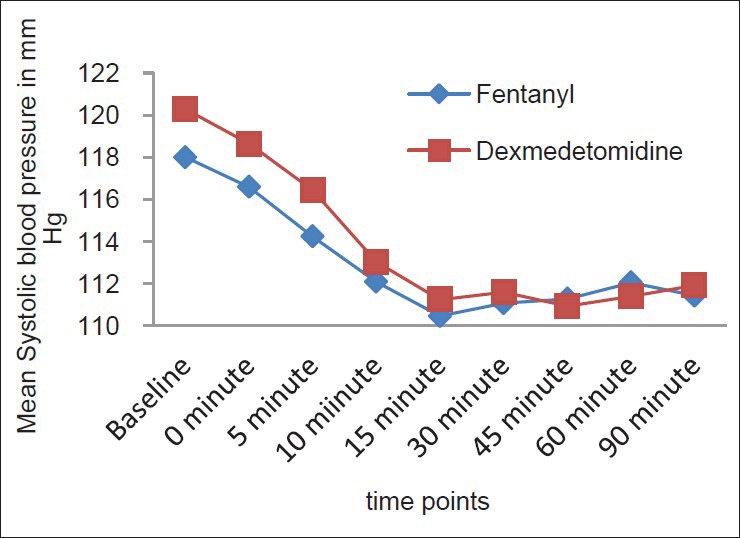

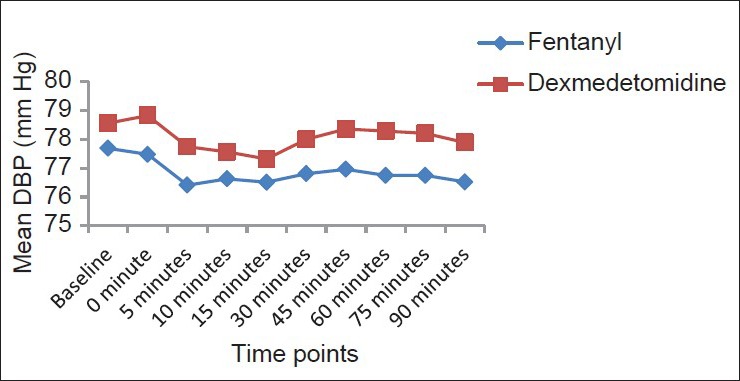

Spinal anaesthesia was successfully accomplished in all patients. The demographic profile, which included patients age, sex, weight, height and ASA grading were similar and no significant difference was observed between the groups [Table 1]. The overall quality of anaesthesia was also similar in both groups [Table 2]. The SBP showed a decreasing trend during the initial 15 min intra-operatively in both groups and thereafter it was stable [Figure 1], but these changes were statistically not significant when compared at corresponding time intervals. No significant changes were observed in case of HR and DBP [Figure 2].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

Table 2.

Quality of anaesthesia

Figure 1.

Intergroup comparison of systolic blood pressure

Figure 2.

Intergroup comparison of diastolic blood pressure

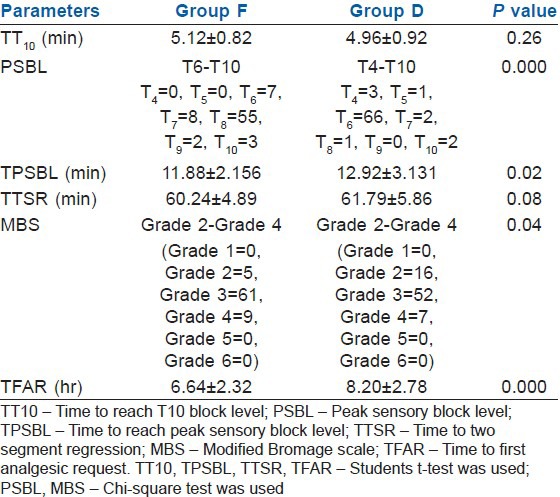

The mean time to reach T10 (TT10) segment (Group F/group D = 5.12/4.96 min) was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). PSBL ranged from T6 to T10 in Group F and T4–T10 in Group D, which was highly significant (P = 0.000). The mean time to reach peak sensory block level (Group F/group D = 11.88/12.92 min) was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The mean TTSR (Group F/Group D = 60.24/61.79 min) was not significant statistically. In both groups, the degree of motor block assessed by MBS ranged from Grade 2 to Grade 4. But, the number of patients achieved Grade 2 block in Group D were more compared with Group F (16 vs. 5) with P = 0.035 which was statistically significant. A highly significant statistical value was achieved (P = 0.000) regarding the mean TFAR: It was 6.64h in Group F and 8.20 h in group D. A summary of sensory and motor block parameters is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of sensory and motor block parameters

DISCUSSION

In this study, it was found that addition of dexmedetomidine to low dose bupivacaine increased the level of sensory block and post-operative analgesic efficacy without significant adverse effects, but with a significant motor blockade. Since almost all lower abdominal surgeries that can be done in the supine position were included, we need an appropriate block level to provide an optimal patient comfort. The cephalad spread of analgesia after spinal block was found to be higher in head tilt group (10° Trendelenberg position) than the horizontal group (supine position) in a previous study.[7] Hence, we decided to tilt the table 5-10° in Trendelenberg position to achieve a desired level.

The use of low dose diluted anaesthetic can shorten recovery time from spinal anaesthesia in addition to limiting the distribution of the block. However, it may not provide an adequate level of sensory block.[2] The addition of fentanyl (25 μg) to low dose bupivacaine (4 mg) has been reported to increase the perioperative quality of spinal blocks with fewer cardiovascular changes,[1,8,9] as has the addition of dexmedetomidine (3 μg) in combination with low dose bupivacaine (6 mg).[10]

Kim et al.[1] observed that fentanyl beyond 25 μg intrathecally produced no benefit in regard to the duration of analgesia. However, fentanyl 25 μg intrathecally with low dose bupivacaine improves post-operative analgesia and haemodynamic stability.[11] At the same time, fentanyl 20μg with bupivacaine 4 mg intrathecally provides spinal anaesthesia with less hypotension[8]; TFAR is also reported to be longer in groups where fentanyl 25 μg was added to low dose bupivacaine.[9]

On the other hand, dexmedetomidine 3 μg with bupivacaine produced a shorter onset of motor blockade, prolonged duration of motor and sensory block with haemodynamic stability and lack of sedation.[12] Gupta et al.[13] observed that 5 μg dexmedetomidine with ropivacaine provided excellent quality of post-operative analgesia with minimal side-effects; and 5 μg dexmedetomidine seems to be an attractive alternative as adjuvant to spinal bupivacaine.[14] Intrathecal dexmedetomidine in doses of 10 μg and 15 μg significantly prolong the anaesthetic and analgesic effects of spinal bupivacaine in a dose dependent manner.[15] Based on the above studies, we had concluded that fentanyl 25 μg and dexmedetomidine 5 μg would be safe and appropriate for our study.

Intrathecally fentanyl exerts its effects by combining with opioid receptors in the dorsal horn of spinal cord and may have a supraspinal spread and action. Intrathecal fentanyl when added to spinal local anaesthetics reduces visceral and somatic pain.[14] Intrathecal α2 receptor agonists have antinociceptive actions for both somatic and visceral pain. Intrathecal dexmedetomidine when combined with spinal bupivacaine prolongs the sensory block by depressing the release of C fibres transmitters and by hyperpolarisation of post synaptic dorsal horn neurons.[13,14]

The density of compounds is believed to be a major determinant in controlling the extent of neural block.[1] Dexmedetomidine is denser than fentanyl and the density of sodium chloride (0.9%) is higher than that of fentanyl and dexmedetomidine. In our study, fentanyl group consisted of bupivacaine 0.8 ml, fentanyl 0.5 ml and normal saline 0.3 ml and dexmedetomidine group consisted of bupivacaine 0.8 ml, dexmedetomidine 0.05 ml and normal saline 0.75 ml. Therefore, the solution with dexmedetomidine was denser and this could be an explanation for the increased level of blockade in dexmedetomidine group as compared with the fentanyl group.

Regarding haemodynamics, no significant difference was observed which is consistent with studies by Ben-David et al.[16] and Atallah et al.[17] where fentanyl was used. In another study where the same dose like our study (fentanyl group) was used for ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery, no incidence of significant hypotension and HR changes were reported.[9] Ben-David et al.[8] found that fentanyl 20 μg with 4 mg bupivacaine provided complete and satisfactory spinal anaesthesia with dramatically less hypotension.

In our study, the time to reach peak sensory block (in min) was higher in Group D (12.92 ± 3.131 vs. 11.88 ± 2.156: P < 0.05) compared to Group F. Since, there was no significant difference in time to reach T10 (in min) (Group F = 5.12 ± 0.82; Group D = 4.96 ± 0.92: P > 0.05) and there was a significant difference in PSBL (Group F = T6-T10; Group D = T4–T10: P =0.000), the significant difference in time to reach PSBL can be accepted.

The higher motor blockade seen in Group D (P = 0.04) may be because of the tendency of α2 receptor agonists to bind with motor neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.[13,14] The TTSR (in min) was not statistically significant among the groups (Group F = 60.24 ± 4.89; Group D = 61.79 ± 5.86: P >0.05). Gurbet et al.[18] reported a two segment regression time of 36 ± 11 min, at a lower dose of bupivacaine (2.5 mg) than that used in the present study. The TFAR (in hours) was longer in Group D than Group F (8.20 ± 2.78 vs. 6.64 ± 2.32; P = 0.000). Gupta et al.[13] report TFAR of 8 h with 5 μg dexmedetomidine and 3 ml ropivacaine 0.75%, Lee[10] found a duration of 8 h with dexmedetomidine 3 μg and Jain et al.[19] reported duration of 5.55 h with 20 μg fentanyl. Al-Ghanem et al.[14] found that 10 mg plain bupivacaine supplemented with dexmedetomidine 5 μg produced prolonged motor and sensory block compared with 25 μg fentanyl similar to the present study.

Limitations of the present study were speed of injection could not be uniform, no preloading was undertaken and hence improper rehydration also might have contributed to reduction in blood pressure. Different types of surgeries were included in this study and no sedation assessment was done.

CONCLUSION

Fentanyl and dexmedetomidine along with low dose bupivacaine provided adequate anaesthesia for all lower abdominal surgeries with haemodynamic stability. However, the clinical advantage of dexmedetomidine over fentanyl is that it facilitates the spread of the block and offers prolonged post-operative analgesia compared to fentanyl.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim SY, Cho JE, Hong JY, Koo BN, Kim JM, Kil HK. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and sufentanil in low-dose dilute bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia for transurethral prostatectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:750–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fournier R, Van Gessel E, Weber A, Gamulin Z. A comparison of intrathecal analgesia with fentanyl or sufentanil after total hip replacement. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:918–22. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200004000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutstein HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Gilman AG, Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2001. pp. 595–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reves JG, Glass PS, Lubarsky DA, McEvoy MD, Martinez-Ruiz R. Intravenous anesthetics. In: Miller RD, editor. Miller's Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone; 2010. pp. 751–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlgren G, Hultstrand C, Jakobsson J, Norman M, Eriksson EW, Martin H. Intrathecal sufentanil, fentanyl, or placebo added to bupivacaine for cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:1288–93. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajwa SJ, Arora V, Kaur J, Singh A, Parmar SS. Comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl for epidural analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:365–70. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyabe M, Namiki A. The effect of head-down tilt on arterial blood pressure after spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:549–52. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199303000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-David B, Frankel R, Arzumonov T, Marchevsky Y, Volpin G. Minidose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anesthesia for surgical repair of hip fracture in the aged. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:6–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unal D, Ozdogan L, Ornek HD, Sonmez HK, Ayderen T, Arslan M, et al. Selective spinal anaesthesia with low-dose bupivacaine and bupivacaine+fentanyl in ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WK. Dresden, Germany: 2011. Sep 7-10, The effects of intrathecal dexmedetomidine on spinal anesthesia using low-dose bupivacaine for transurethral resection of prostate in the elderly. Poster Session Presented at 30th Annual ESRA Congress. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chavda H, Mehta PJ, Vyas AH. A comparative study of intrathecal fentanyl and sufentanil with bupivacaine heavy for postoperative analgesia. [Last accessed on 2012 Mar 20];Internet J Anesthesiol. 2009 20 Available from: http://ispub.com/IJA/20/2/7190 . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanazi GE, Aouad MT, Jabbour-Khoury SI, Al Jazzar MD, Alameddine MM, Al-Yaman R, et al. Effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine or clonidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:222–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R, Bogra J, Verma R, Kohli M, Kushwaha JK, Kumar S. Dexmedetomidine as an intrathecal adjuvant for postoperative analgesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:347–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.84841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Ghanem SM, Massad IM, Al-Mustafa MM, Al-Zaben KR, Qudaisat IY, Qatawneh AM, et al. Effect of adding dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl to intrathecal bupivacaine on spinal block characteristics in gynaecological procedures: A double blind controlled study. Am J Appl Sci. 2009;6:882–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eid HE, Shafie MA, Youssef H. Dose related prolongation of hyperbaric bupivacaine spinal anesthesia by dexmedetomidine. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol. 2011;4:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben-David B, Miller G, Gavriel R, Gurevitch A. Low-dose bupivacaine-fentanyl spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:235–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atallah MM, Shorrab AA, Abdel Mageed YM, Demian AD. Low-dose bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: The suitability and impact of adding intrathecal fentanyl. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:798–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurbet A, Turker G, Girgin NK, Aksu H, Bahtiyar NH. Combination of ultra-low dose bupivacaine and fentanyl for spinal anaesthesia in out-patient anorectal surgery. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:964–70. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain K, Grover VK, Mahajan R, Batra YK. Effect of varying doses of fentanyl with low dose spinal bupivacaine for caesarean delivery in patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]