Abstract

AIM: To identify risk factors for surgical failure after colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery in left-sided malignant colonic obstruction.

METHODS: The medical records of patients who underwent stent insertion for malignant colonic obstruction between February 2004 and August 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with malignant colonic obstruction had overt clinical symptoms and signs of obstruction. Malignant colonic obstruction was diagnosed by computed tomography and colonoscopy. A total of 181 patients underwent stent insertion during the study period; of these, 68 consecutive patients were included in our study when they had undergone stent placement as a bridge to surgery in acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction due to primary colon cancer.

RESULTS: Out of 68 patients, forty-eight (70.6%) were male, and the mean age was 64.9 (range, 38-89) years. The technical and clinical success rates were 97.1% (66/68) and 88.2% (60/68), respectively. Overall, 85.3% (58/68) of patients underwent primary tumor resection and primary anastomosis. Surgically successful preoperative colonic stenting was achieved in 77.9% (53/68). The mean duration, defined as the time between the SEMS attempt and surgery, was 11.3 d (range, 0-26 d). The mean hospital stay after surgery was 12.5 d (range, 6-55 d). On multivariate analysis, the use of multiple self-expanding metal stents (OR = 28.872; 95%CI: 1.939-429.956, P = 0.015) was a significant independent risk factor for surgical failure of preoperative stenting as a bridge to surgery. Morbidity and mortality rates in surgery after stent insertion were 4.4% (3/68) and 1.5% (1/68), respectively.

CONCLUSION: The use of multiple self-expanding metal stents appears to be a risk factor for surgical failure.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Endoscopy, Intestinal obstruction, Risk factors, Stents

Core tip: When self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) is used as a bridge to surgery, the goal is a successful surgical outcome. When surgical results are not good after colonic stenting in patients with malignant colonic obstruction (MCO), many physicians have wondered about the risk factors of surgical failure and wanted to improve their results. Our results show that the use of multiple SEMS was an independent risk factor for surgical failure on multivariate analysis. The identification of this risk factor might help physicians make decisions regarding an appropriate modality for patients with acute left-sided MCO and should provide a foundation for establishing a consensus on treatment strategies in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 8%-29% of colon cancer patients present with obstructive symptoms on diagnosis[1]. Malignant colonic obstruction (MCO) requires urgent decompression because it may result in colonic necrosis and perforation due to colonic mucosal friability, which is the result of massive colon distension[2].

Conventionally, MCO has been managed by emergency surgical procedures, including loop colostomy followed by colostomy reversal. The formation of a stoma is known to have a negative impact on aspects of health-related quality of life in patients, and the stoma is eventually left unclosed in many patients[1,3,4]. Furthermore, emergency colonic surgery in this setting often leads to higher mortality (8%-24%), morbidity (46%-62%), and incidence of stoma retention than elective surgery due to the poor general condition and lack of bowel preparation of the patient[2,3,5,6].

It is necessary, therefore, to identify other alternatives for MCO decompression in order to avoid emergency surgery. One effective method is the use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) in patients with MCO. Previous reports have offered strong evidence of their advantages, such as high effectiveness and fewer complications[7-10]. Recently, however, increased emphasis has been placed on using colonic stents as a bridge to surgery (BTS). Additionally, there is an increasing controversy regarding the efficacy and long-term outcomes of stenting as a BTS compared to emergency surgery for MCO[3,11].

When a SEMS is used as a BTS, the goal is the achievement of a successful surgical outcome. However, there has been no report on the predictors of poor surgical outcomes after stenting as a BTS. The aim of this study was to identify the risk factors for surgical failure after colonic stenting as a BTS in patients with acute left-sided MCO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The medical records of patients who underwent SEMS placement for MCO at Gachon University Gil Medical Center (Incheon, Korea) from February 2004 to August 2012 were retrospectively reviewed.

SEMS as a BTS was attempted in eligible patients with acute left-sided MCO. Patients with MCO had overt clinical symptoms and signs of obstruction. MCO was diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) and colonoscopy, whereas CT confirmed the presence of obstructive lesions by identifying upstream colonic dilatation, with colonoscopic confirmation if an inability to pass the endoscope proximally was noted.

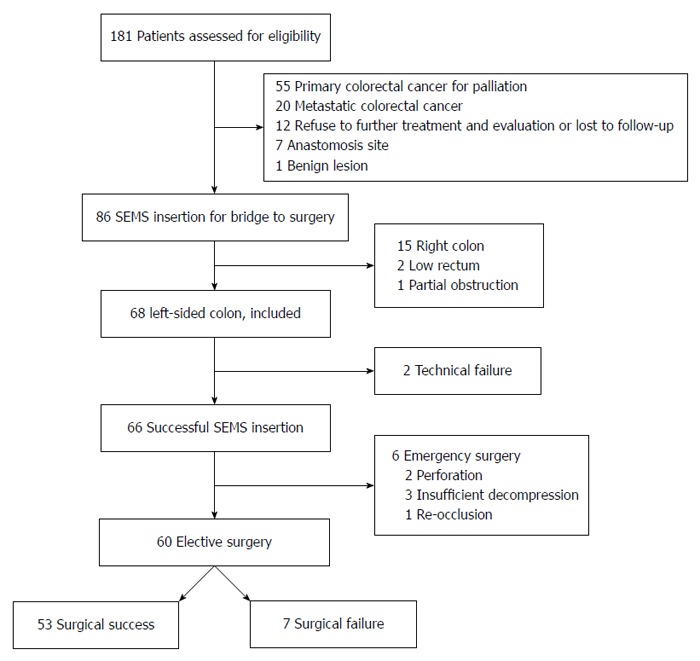

A total of 181 patients underwent SEMS insertion under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance during the study period. Patients were excluded if they fell within any of the following categories: stenting for palliation (n = 55) or for obstruction caused by metastatic colon cancer (n = 20) or a benign disease (n = 1); anastomosis site stenosis (n = 7); refusal of further treatment and evaluation or loss during follow-up (n = 12); right colonic obstruction (n = 15); distal tumor margin of less than 10 cm from the anal verge (n = 2); and partial obstruction allowing endoscopic passage (n = 1). A total of 68 consecutive patients were included in our study after having undergone SEMS placement as a BTS in acute left-sided MCO due to primary colon cancer (Figure 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University Gil Medical Center (IRB No. GDIRB2013-09).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing patient selection in this study. SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents.

Procedure details

Informed consent was obtained from patients after an adequate explanation of the procedure. Enema was performed in all patients several hours before the procedure. A two-channel therapeutic endoscope (GIF-2T240; Olympus Optical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) or colonoscope (CF-Q240L; Olympus) was used. For stenting, ComVi Enteral Colonic Stents (Taewoong Medical Co., Seoul, South Korea) and Niti-S Enteral Colonic Stents (Taewoong Medical Co.) were used.

As previously reported[7,10,12], SEMS were inserted by the following process. The colonoscope was first introduced to the obstruction site, followed by the passage of a guidewire through the stricture under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance. After measuring the length of the stricture with CT and/or barium enema and/or fluoroscopy using water soluble contrast, a stent at least 3 cm longer than the stricture was chosen to adequately bridge the stricture. Covered or uncovered stents were selected depending on the endoscopists’ preference. To confirm the appropriate stent positioning and expansion, repeated simple radiograms were made during hospitalization. Balloon dilatation of the stricture was not performed.

After SEMS insertion as a BTS, a pre-operative evaluation was performed, and the time of elective surgery was determined by the attending surgeon following an assessment of the patient’s bowel function and clinical condition. Two surgeons specializing in coloproctology performed the operations, and the type of procedure was determined by the surgeon depending on the location of the primary disease and the intraoperative conditions of the patient. Patients with successful SEMS placement were deemed eligible for elective surgery and received a bowel preparation using 2-4 liters of polyethylene glycol in the evening before surgery and a single dose of first-generation cephalosporin for antibiotic prophylaxis 30 min before anesthetic induction. At the surgeons’ discretion, continuous antibiotic therapy was employed as deemed necessary. Primary tumor resection and primary anastomosis (PTRPA) were performed when possible.

Definition

The technical success rate was defined as the ratio of patients with correctly placed SEMS upon stent deployment across the entire stricture length to the total number of patients. The clinical success rate was defined as the ratio of patients with technical success and successful maintenance of stent function before elective surgery, regardless of the number of SEMS deployed to the total number of patients.

The surgical success rate of SEMS as a BTS was defined as the ratio of patients with successful surgical outcomes, such as successful PTRPA, to the total number of patients. Unsuccessful surgical outcomes were defined as the failure of PTRPA or subtotal/total colectomy due to insufficient colonic decompression. Surgical failure was thus inclusive of technical failure, unplanned surgery, and total/subtotal colectomy due to insufficient decompression.

PTRPA was defined as the surgical procedure used to reconnect two sections of the colon following primary resection of the tumor. Multiple SEMS was defined as having at least two stents deployed at the first session or undergoing more than two stenting sessions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 12.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) for MS Windows®. Continuous data are presented as means (range) and categorical data as absolute numbers and percentages. For univariate analysis, continuous data were analyzed using the independent t-test, and other categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis by logistic regression was performed using the statistically significant variables found in the univariate analysis. Two-tailed P-values of 0.05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The baseline data for the patients are summarized in Table 1. Out of 68 patients, forty-eight (70.6%) were male, and the mean age was 64.9 years (range, 38-89 years). None had received prior chemotherapy, and each first presented as acute obstruction due to primary colon cancer. The most commonly obstructed site was the rectosigmoid junction (25/68, 36.8%), and the second most common site was the sigmoid colon (22/68, 32.4%). Covered SEMS were used in 50.0% (33/66) of patients with technical success. The mean duration, defined as the time between SEMS attempts and surgery, was 11.3 d (range, 0-26 d). The mean hospital stay after surgery was 12.5 d (range, 6-55 d).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients n (%)

| Total (n = 68) | |

| Age (yr) | 64.9 (38-89) |

| Male/female | 48 (70.6)/20 (29.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 (17.7-31.9) |

| Previous IA surgery | 19 (27.9) |

| Laboratory findings | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.4 (7.2-17.3) |

| White blood cells (/mm3) | 8471.7 (3050-19850) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 (2.5-5.2) |

| ASA classification | |

| 1 | 11 (16.2) |

| 2 | 50 (73.5) |

| 3 | 7 (10.3) |

| TNM Stage of tumor | |

| II | 22 (32.4) |

| III | 26 (38.2) |

| IVA | 20 (29.4) |

| Histology | |

| WD | 8 (11.8) |

| MD | 57 (83.8) |

| PD | 3 (5.6) |

| Location of obstruction | |

| Sigmoid flexure | 5 (7.4) |

| Descending colon | 7 (10.3) |

| Sigmoid-descending area | 9 (13.2) |

| Sigmoid colon | 22 (32.4) |

| Recto-sigmoid area | 25 (36.8) |

BMI: Body mass index; IA: Intra-abdominal; ASA: American society of anesthesiologists; WD: Well-differentiated cancer; MD: Moderate-differentiated cancer; PD: Poorly-differentiated cancer.

Success rate

In the first attempt, 66 of 68 patients (97.1%) achieved a technically successful placement of SEMS. SEMS insertion was not successful in two patients, in one due to failure of guide wire passage through the completely obstructed stricture (descending colon), and in the other, due to acute angulation of the colonic flexure, which caused difficulty in guide wire passage (rectosigmoid junction) (Table 2). They eventually underwent emergency surgery.

Table 2.

Etiology of surgical failure in patients undergoing stenting as a bridge to surgery n (%)

|

Emergency surgery (n = 8) |

Elective surgery (n = 60) |

Total (n = 68) | |||

| PTRPA(-) (n = 5) | PTRPA(+) (n = 3) | PTRPA(-) (n = 5) | PTRPA(+) (n = 55) | ||

| Surgical failure | |||||

| Technical failure | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.9) |

| Stent-related complications | |||||

| Perforation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.9) |

| Re-obstruction | 11 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 2 (2.9) |

| Insufficient decompression | 2 | 1 | 21 | 0 | 5 (7.4) |

| Unsatisfactory surgical results | |||||

| PTRPA not feasible | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 (4.4) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (1.5) |

| Surgical success | |||||

| Stent-related complications | |||||

| Insufficient decompression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 (1.5) |

| Migration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (2.9) |

| Satisfactory surgical results | 50 | 50 (73.5) | |||

Multiple SEMS was defined as a number of stent ≥ 2 at the first session or a session number ≥ 2;

Patients undergoing subtotal colectomy. PTRPA: Primary tumor resection and primary anastomosis.

Clinical success was achieved in 88.2% (60/68) of patients. Clinical failure occurred in 8, who then required emergency surgery (Figure 1 and Table 2). Six patients, not counting the two who experienced technical failures, encountered clinical failure due to complications: two with perforation, one with re-obstruction, and three with insufficient decompression. The mean time from stent placement to surgery was 2.1 d (range, 0-8 d) in patients with clinical failure and 12.6 d (range, 4-26 d) in those with clinical success.

Successful PTRPA was achieved in 85.3% (58/68) of patients, including one following technical failure and 57 following technical success. In detail, failure in PTRPA occurred in five patients (5/8, 62.5%) following clinical failure and five (5/60, 8.3%) following clinical success.

In patients with clinical success, 7 patients did not achieve surgical success. In three, stent-related complications were the cause of surgical failure. The remaining four failed surgically due to unsuccessful surgical outcomes. The surgical success rate of SEMS as a BTS was 77.9% (53/68).

Complication and surgical outcomes

Complications were observed during the first 60 d after SEMS placement, including both stent-related and surgery-related complications (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Types of and complications due to operations after colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery n (%)

| Complications | Value |

| Type of operation (n = 68) | |

| Anterior resection | 27 (39.7) |

| Left hemicolectomy | 13 (19.1) |

| Low anterior resection | 12 (17.6) |

| Hartmann’s operation | 7 (10.3) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 3 (4.4) |

| Stoma creation | 1 (1.5) |

| Quadrantectomy | 1 (1.5) |

| Anterior resection with ileostomy | 1 (1.5) |

| Total colectomy | 1 (1.5) |

| Low anterior resection with ileostomy | 1 (1.5) |

| Segmental resection en bloc | 1 (1.5) |

| Surgery-related complications (n = 68) | |

| Wound infection | 1 (1.5) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (1.5) |

| Anastomosis leakage | 1 (1.5) |

Procedure-related complications were observed in 12 cases. Of these, two patients experienced perforation and underwent emergency surgery. The stent was observed to be in situ during elective surgery, except in two patients in whom clinically silent migration had occurred; they both underwent successful PTRPA. Another two patients with re-obstruction due to stool impaction underwent a second stent placement 1 and 3 d after the first stent insertion, respectively. One of the patients with re-obstruction was successfully re-stented 1 d after the first stent insertion; an emergency Hartmann’s operation was subsequently required due to insufficient decompression. The other patient, who underwent stent reinsertion 3 d after the first stent insertion, received an elective operation; however, subtotal colectomy was required due to inadequate colonic decompression 13 d after the first stent placement. The remaining six patients with insufficient decompression included three who underwent emergency operations and three who underwent elective surgery.

Postsurgical complications occurred in 3/68 of patients; these patients underwent elective surgery (Table 3). These three patients experienced anastomosis leakage, wound infection, or pneumonia. The patient who underwent a segmental resection en bloc after successful stenting developed anastomotic leakage three days after surgery and had to undergo a re-operation for colostomy of the transverse colon. The patient with wound infection recovered after antibiotic treatment and was discharged 10 d after surgery. The patient who had pneumonia eventually passed away 6 d after elective surgery (left hemicolectomy); he had underlying medical conditions including hypertension and previous subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for overall stent failure

Comparisons between patients with surgical failures and successes following technical success are summarized in Table 4. There were no differences between the two groups in terms of age, gender, or history of previous intra-abdominal surgery. Anemia (male < 13 g/dL, female < 12 g/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 3.5 g/dL) were more common in the surgical failure group, and leukocytosis (> 10000/mm3) was more common in the surgical success group, although there were no significant differences. Body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2 was significantly more common in the failure group (23.1% vs 1.9%, P = 0.004).

Table 4.

Comparison of factors related to surgical failure and success in patients achieving technical success n (%)

| Surgical failure (n = 13) | Surgical success (n = 53) | P value | |

| Patient-related factor | |||

| Age > 70 yr | 6 (46.2) | 20 (37.7) | 0.578 |

| Male | 10 (76.9) | 36 (67.9) | 0.727 |

| BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 | 3 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.004 |

| Previous IA surgery | 3 (23.1) | 16 (30.2) | 0.612 |

| Anemia | 9 (69.2) | 28 (52.8) | 0.286 |

| Leukocytosis | 2 (15.4) | 14 (26.4) | 0.406 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 6 (46.2) | 11 (20.8) | 0.061 |

| ASA 1-2 | 12 (92.3) | 47 (88.7) | 0.703 |

| Tumor-related factor | |||

| WD and MD cancer | 13 (100) | 50 (94.3) | 0.380 |

| TNM stage III-IVA | 12 (92.3) | 32 (60.4) | 0.029 |

| Obstructive site | 0.511 | ||

| Sigmoid flexure | 0 (0) | 5 (9.4) | |

| Descending colon | 0 (0) | 6 (11.3) | |

| Sigmoid-descending area | 2 (15.4) | 7 (13.2) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 5 (38.5) | 17 (32.1) | |

| Recto-sigmoid colon | 6 (46.2) | 18 (34.0) | |

| Flexure area | 8 (61.5) | 30 (56.6) | 0.747 |

| Stent-related factor | |||

| Uncovered | 6 (46.2) | 27 (50.9) | 0.757 |

| Diameter ≤ 22 (mm) | 9 (62.5) | 34 (64.2) | 0.731 |

| Length ≥ 10 (cm) | 8 (61.5) | 27 (50.9) | 0.493 |

| Multiple SEMS | 4 (30.8) | 1 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Interval from SEMS to surgery (d) | 9.8 (0-26) | 12.1 (4-26) | 0.354 |

| Hospital stay after surgery (d) | 15.4 (7-44) | 11.7 (6-55) | 0.151 |

BMI: Body mass index; IA: Intra-abdominal; ASA: American society of anesthesiologists; WD: Well-differentiated cancer; MD: Moderate-differentiated cancer; SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents.

Advanced stages, defined as stages III and IVA, were significantly more common in the surgical failure group than in the surgical success group (92.3% vs 60.4%, P = 0.029). The flexure area was more frequently obstructed in the surgical failure group than in the success group, but there was no significant difference.

Variables related to stent characteristics, including length or diameter of stent and stent type, were not identified as risk factors for surgical failure. However, the use of multiple SEMS was significantly more common in the surgical failure group (30.8% vs 1.9%, P < 0.001).

On multivariate analysis, only multiple SEMS was a significant risk factor correlating to surgical failure (OR = 28.872; 95%CI: 1.939-429.956, P = 0.015) (Table 5). In five patients who underwent multiple SEMS, only one patient (1/5, 20%) who received two SEMS in the first session due to insufficient decompression met with surgical success (Table 2). Two of the remaining patients who underwent elective surgery received two SEMS in the first session due to insufficient decompression and eventually underwent Hartmann’s operation. The remaining two patients underwent a second stenting session due to re-obstruction; one underwent emergency surgery, and the other, a subtotal colectomy.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for surgical failure in patients achieving technical success

| OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| BMI | |||

| ≥ 18.5 | 1 (reference) | ||

| < 18.5 | 9.759 | 0.784-121.527 | 0.077 |

| TNM stage | |||

| II | 1 (reference) | ||

| III and IVA | 7.685 | 0.666-88.722 | 0.102 |

| Multiple SEMS | |||

| No | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 28.872 | 1.939-429.956 | 0.015 |

BMI: Body mass index; SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the technical success rate was 97.1%, which is comparable to the rates of previous studies, which range from 70.7% to 96.2%, according to systematic reviews and pooled/meta-analyses[2,9,13]. The definition of a clinically successful stent deployment differed slightly among these studies. Several of the previous studies defined clinical success based on intestinal transit or flatus/stool passage within 1-3 d after the procedure[13-15]. In this study, clinical success was defined as the achievement of colonic decompression with stool passage between stent placement and elective surgery, which conforms to the intention of deploying colonic stents as a BTS. Based on this definition, the clinical success rate was 88.2% in this study, which is consistent with the reported rates of 69.0%-92.0%[2,16].

When a SEMS is used as a BTS, the purpose is to obtain a successful surgery that facilitates optimal outcomes and permits PTRPA. Therefore, unlike in other studies, surgical success, defined as the feasibility of PTRPA as elective surgery except for subtotal/total colectomy caused by poor bowel decompression, was also assessed. BTS stenting allowed for surgical success in 77.9% of all patients; this result is relatively high compared to the rates in the range of 55.3%-64.9% that have been reported in previous studies[17,18]. The reason for this may be that the denominator in the success rate of the SEMS group (defined as patients with SEMS insertion as a BTS) included patients with technical failure (who actually underwent emergency surgery) for analysis on an intention-to-treat basis, and the technical failure rates in other prospective studies were higher than in this study.

SEMS as a BTS showed conflicting outcomes in a recent meta-analysis and in randomized trials[2,14,18-20]. The endoscopists who participated in these trials had some differences in their levels of experience and skill[21,22]. Low technical success in SEMS placement might have been the main cause of their negative results for the deployment of SEMS. It would not be reasonable, therefore, to generalize the conclusions of some of the reports that SEMS is not advantageous as a BTS because an endoscopist’s experience and skill are important factors in colonic stenting. For patients in whom SEMS placement was attempted as a BTS in MCO, previous studies have reported that the factors associated with technical failure included the severity of obstruction, the extra-colonic origin of tumor, the proximal colonic obstruction, and the presence of carcinomatosis[14,23]. In this study, the factors associated with technical failure could not be analyzed because the incidence of technical failure (2 cases) was too low.

In patients undergoing emergency surgery without SEMS insertion before surgery (the surgery group), the previously published stoma formation rates are 32%-57%[4,15,24]. When the SEMS group included patients with technical failure, the initial stoma formation rates for the SEMS group were 40%-53%[4,15]. No difference is apparent between the two groups. However, the primary stoma formation rate in the present study was 14.7% (10/68), with only 5 patients (5/60, 8.3%) requiring a diverting stoma in patients with clinical success. The remaining 5 patients (5/8, 62.5%) with clinical failure underwent stoma creation due to stent-related complications (n = 4) and technical failure (n = 1). This result suggests that BTS stenting is advantageous if SEMS insertion is technically successful and if function is well-maintained up to surgery[5,15].

The focus of this study was to identify risk factors for surgical failure in patients with technical success. The use of multiple SEMS was an independent risk factor for surgical failure on multivariate analysis. Currently, when strictures are not adequately covered or decompressed by a single SEMS or in a single session, the option is to immediately place a second stent or to undergo another session, as needed[25]. In the present study, out of the five patients who had undergone multiple SEMS placement, clinical success was achieved in four, allowing for elective surgery. However, only one patient achieved surgical success. Repeated attempts at colonic decompression using SEMS increased the clinical success rate, but the surgical success, the essential purpose of BTS stenting, was unachieved. Although the present study has found that the use of multiple SEMS is an independent risk factor for surgical failure, this may not necessarily mean that, upon the clinical failure of a single SEMS, surgery should be immediately considered as the next course of action. There is still no consensus in the literature regarding this relationship and further data is required to establish it.

When using stents for palliation of MCO, the stent length (≥ 10 cm) and diameter (≤ 22 mm) are reported to be risk factors for poor long-term outcomes of SEMS[26,27]. Patient- and tumor-related factors and characteristics of SEMS were not identified as risk factors for surgical failure in the present study. BTS stenting differs from palliative stenting in that, for the former, the functionality of the SEMS must be maintained until elective surgery.

In this study, one case (1/68, 1.5%) of intra-procedural complications and eleven cases (11/68, 16.2%) of post-procedural complications were observed, which is comparable to the results of other studies on colonic stenting as a BTS with rates of 7%-24%[14,24,27]. Two patients in whom covered stents were inserted experienced migration. This may have been due to the smooth surface of the stent and their less severe colonic obstruction. Although the potential for tumor cell dissemination due to perforation is unclear, perforation is the most significant complication of SEMS[15] .Balloon dilation, specifically designed stents, and chemotherapy are considered contributing factors associated with stent-related perforation[8,28]. Two cases of perforation occurred in 68 patients in the present study. This result is lower than the 3%-9% reported in previously published studies[16,24,27,29], most likely because none of the patients in this study were associated with these factors.

Morbidity and mortality rates in surgery after SEMS insertion were 3/68 (4.4%) and 1/68 (1.5%), respectively, and are comparable to the respective reported rates of 0%-36% and 0%-9% from other studies on colonic stenting as a BTS[5,6,17,24]. All of these data represent patients who underwent elective surgery. However, it is difficult to analyze the contributing factors because of the small sample size and rarity of such events in this study.

The mean duration between successful stenting and elective surgery [12.1 d (range, 4-26 d)] was relatively longer than that reported in other studies[14,24], and the increase in the complication rates may have been due to this short interval (5-16 d). A sufficient interval between SEMS placement and surgery is required to allow for optimal decompression and improvement of the patient’s clinical condition[14,24]. However, there is no consensus on the optimal stent-to-surgery duration for bowel decompression and improvement under clinical conditions.

The beneficial efficacy of the SEMS as a BTS on right-sided colon cancer is obviously controversial. Obstructive right sided colon cancers can be treated by PTRPA, even in emergency settings, which is why we did not include right-sided obstructions in our study[30].

This is a retrospective study at a single tertiary center, and thus the possibility of selection bias cannot be ruled out. In addition, patients with severe obstruction would have been more likely to receive emergency surgery than stent insertion as a BTS. The confidence interval was so wide that the statistical power was not high enough to interpret and generalize the study results. Additionally, the use of multiple SEMS most likely suggests a difficult, severe stricture. This may be explained by the fact that the number of patients included in this study was relatively small. Despite these limitations, this study suggests that the use of SEMS is an effective BTS with an acceptable complication rate in most patients.

In conclusion, the finding that the use of multiple SEMS is an independent risk factor for surgical failure may aid in therapeutic decision-making between surgery and endoscopic stenting in patients with acute left-sided MCO. Larger, prospective studies on the clinical impact of multiple SEMS as a BTS appear to be necessary to confirm the findings presented in this report.

COMMENTS

Background

It is necessary to identify other alternatives for the decompression of malignant colonic obstruction (MCO) in order to avoid emergency surgery. One effective method is using self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) in patients with MCO. Previous reports have offered strong evidence of their advantages, such as high effectiveness and fewer complications. However, there has been no report on the predictors of poor surgical outcomes after stenting as a bridge to surgery (BTS).

Research frontiers

Most of the previous studies have been focused on the technical and clinical success of SEMS. However, when SEMS are used as a BTS, the goal is a successful surgery that enables the optimal outcome to be achieved and permits primary tumor resection and primary anastomosis (PTRPA). Therefore, unlike other studies, the aim of this study was to identify risk factors for surgical failure after colonic stenting as a BTS in patients with MCO.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The focus of this study was to identify the risk factors for surgical failure in patients with technical success. In this study, repeated attempts at colonic decompression using SEMS increased the clinical success rate, but surgical success, the essential purpose of BTS stenting, remained unachieved. These results constitute very important and interesting findings. Still, although the present study has found the use of multiple SEMS to be an independent risk factor for surgical failure, this may not necessarily mean that, upon the clinical failure of single SEMS, surgery should immediately be entertained as the next course of action.

Applications

The use of multiple SEMS was an independent risk factor for surgical failure, upon multivariate analysis. Currently, when strictures are not adequately covered or decompressed by a single stent or in a single session, the option is to immediately place a second stent or to undergo another session, as needed. These findings may aid in the therapeutic decision-making between surgery and endoscopic stenting in patients with acute left-sided MCO.

Terminology

The surgical success rate of SEMS as a BTS was defined as the ratio of patients with successful surgical outcomes, such as successful PTRPA, to the total number of patients. Unsuccessful surgical outcomes were defined as the failure of PTRPA or subtotal/total colectomy due to insufficient colonic decompression. Surgical failure was thus inclusive of technical failure, unplanned surgery, and total/subtotal colectomy due to insufficient decompression. Multiple SEMS was defined as having at least two stents deployed at the first session or undergoing more than two stenting sessions.

Peer review

This is a very interesting paper that looked into an important problem in the clinical field, taking an original stance. Multiple SEMS, as concluded in the multivariate analysis, seems to be a significant independent risk factor of surgical failure.

Footnotes

Supported by A grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Fare, Republic of Korea, No. HI13C-1602-010013; grants of the Gachon University Gil Medical Center, No. 2013-01 and 2013-37

P- Reviewer: Figueiredo PN, Ladas SD, Jeon SW S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Deans GT, Krukowski ZH, Irwin ST. Malignant obstruction of the left colon. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan CJ, Dasari BV, Gardiner K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of self-expanding metallic stents as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for malignant left-sided large bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2012;99:469–476. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Santos C, Lobato RF, Fradejas JM, Pinto I, Ortega-Deballón P, Moreno-Azcoita M. Self-expandable stent before elective surgery vs. emergency surgery for the treatment of malignant colorectal obstructions: comparison of primary anastomosis and morbidity rates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:401–406. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight AL, Trompetas V, Saunders MP, Anderson HJ. Does stenting of left-sided colorectal cancer as a “bridge to surgery” adversely affect oncological outcomes? A comparison with non-obstructing elective left-sided colonic resections. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1509–1514. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho KS, Quah HM, Lim JF, Tang CL, Eu KW. Endoscopic stenting and elective surgery versus emergency surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:355–362. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cennamo V, Luigiano C, Coccolini F, Fabbri C, Bassi M, De Caro G, Ceroni L, Maimone A, Ravelli P, Ansaloni L. Meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing endoscopic stenting and surgical decompression for colorectal cancer obstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:855–863. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1599-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee JJ, Chung JW, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim JH, Hahm KB. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for colorectal obstruction with unresectable stage IVB colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2472–2476. doi: 10.5754/hge12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khot UP, Lang AW, Murali K, Parker MC. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1096–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2051–2057. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Ku YS, Jeon TJ, Park JY, Chung JW, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim YJ. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for malignant colorectal obstruction by noncolonic malignancy with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1228–1232. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a411e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JS, Hur H, Min BS, Sohn SK, Cho CH, Kim NK. Oncologic outcomes of self-expanding metallic stent insertion as a bridge to surgery in the management of left-sided colon cancer obstruction: comparison with nonobstructing elective surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:1281–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee WS, Baek JH, Kang JM, Choi S, Kwon KA. The outcome after stent placement or surgery as the initial treatment for obstructive primary tumor in patients with stage IV colon cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;203:715–719. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung HY, Chung CC, Tsang WW, Wong JC, Yau KK, Li MK. Endolaparoscopic approach vs conventional open surgery in the treatment of obstructing left-sided colon cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1127–1132. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA, Oldenburg B, Marinelli AW, Lutke Holzik MF, Grubben MJ, Sprangers MA, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P. Colonic stenting versus emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:344–352. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirlet IA, Slim K, Kwiatkowski F, Michot F, Millat BL. Emergency preoperative stenting versus surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1814–1821. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watt AM, Faragher IG, Griffin TT, Rieger NA, Maddern GJ. Self-expanding metallic stents for relieving malignant colorectal obstruction: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2007;246:24–30. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000261124.72687.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye GY, Cui Z, Chen L, Zhong M. Colonic stenting vs emergent surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5608–5615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Listorti C, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Sagar J. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery in the management of intestinal obstruction due to left colon and rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagar J. Colorectal stents for the management of malignant colonic obstructions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD007378. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007378.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Shi J, Shi B, Song CY, Xie WF, Chen YX. Self-expanding metallic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for obstructive colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:110–119. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song LM, Baron TH. Stenting for acute malignant colonic obstruction: a bridge to nowhere? Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:314–315. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung DY, Lee YK, Yang CH. Status and literature review of self-expandable metallic stents for malignant colorectal obstruction. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:65–73. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon JY, Jung YS, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for technical and clinical failures of self-expandable metal stent insertion for malignant colorectal obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiménez-Pérez J, Casellas J, García-Cano J, Vandervoort J, García-Escribano OR, Barcenilla J, Delgado AA, Goldberg P, Gonzalez-Huix F, Vázquez-Astray E, et al. Colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery in malignant large-bowel obstruction: a report from two large multinational registries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2174–2180. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Ross WA, Davila R, Chang G, Lin E, Dekovich A, Davila M. Self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) can serve as a bridge to surgery or as a definitive therapy in patients with an advanced stage of cancer: clinical experience of a tertiary cancer center. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3530–3536. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung MK, Park SY, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Kim GC, Ryeom HK. Factors associated with the long-term outcome of a self-expandable colon stent used for palliation of malignant colorectal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:525–530. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small AJ, Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron TH. Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal stents for malignant colonic obstruction: long-term outcomes and complication factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Hooft JE, Fockens P, Marinelli AW, Timmer R, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Bemelman WA. Early closure of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgery for stage IV left-sided colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40:184–191. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meisner S, Hensler M, Knop FK, West F, Wille-Jørgensen P. Self-expanding metal stents for colonic obstruction: experiences from 104 procedures in a single center. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, Brouquet A, Cervantes A. Primary colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v70–v77. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]