Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the usefulness of three-dimensional (3D) shear-wave elastography (SWE) in assessing the liver ablation volume after radiofrequency (RF) ablation.

METHODS: RF ablation was performed in vivo in 10 rat livers using a 15-gauge expandable RF needle. 3D SWE as well as B-mode ultrasound (US) were performed 15 min after ablation. The acquired 3D volume data were rendered as multislice images (interslice distance: 1.10 mm), and the estimated ablation volumes were calculated. The 3D SWE findings were compared against digitized photographs of gross pathological and histopathological specimens of the livers obtained in the same sectional planes as the 3D SWE multislice images. The ablation volumes were also estimated by gross pathological examination of the livers, and the results were then compared with those obtained by 3D SWE.

RESULTS: In B-mode US images, the ablation zone appeared as a hypoechoic area with a peripheral hyperechoic rim; however, the findings were too indistinct to be useful for estimating the ablation area. 3D SWE depicted the ablation area and volume more clearly. In the images showing the largest ablation area, the mean kPa values of the peripheral rim, central zone, and non-ablated zone were 13.1 ± 1.5 kPa, 59.1 ± 21.9 kPa, and 4.3 ± 0.8 kPa, respectively. The ablation volumes depicted by 3D SWE correlated well with those estimated from gross pathological examination (r2 = 0.9305, P = 0.00001). The congestion and diapedesis of red blood cells observed in histopathological examination were greater in the peripheral rim of the ablation zone than in the central zone.

CONCLUSION: 3D SWE outperforms B-mode US in delineating ablated areas in the liver and is therefore more reliable for spatially delineating thermal lesions created by RF ablation.

Keywords: Radiofrequency ablation, Liver, Ultrasound, Shear-wave elastography, Three-dimensional

Core tip: Three-dimensional shear-wave elastography is a reliable noninvasive technique that may be useful for the real-time assessment of treatment efficacy immediately after radiofrequency ablation procedures. It is superior to B-mode ultrasound in delineating the ablated areas in the liver. The threshold value for determining remaining cell viability was found to be 13.1 ± 1.5 kPa.

INTRODUCTION

Radiofrequency (RF) ablation has recently been reported to be useful for the treatment of malignant liver tumors[1,2]. Because of its ease of use, widespread availability, potential for repeated use in solitary or multifocal hepatic disease, and low cost compared with laparoscopic and open surgical approaches, the range of applications of RF ablation has been expanding to include the treatment of malignancies in a variety of organs.

On the other hand, a notable disadvantage of RF ablation is its lower success rate for complete local tumor eradication compared with more invasive surgical methods[3]. The ability to perform evaluation during or immediately after ablation procedures would therefore be very helpful, making it possible to determine the completeness of ablation in real time and to perform further intervention if remaining viable tumor is found.

In recent decades, there has been an increasing interest in assessing the viscoelastic properties of tissues using ultrasound (US) elastography. Among the various techniques employed in US elastography, shear-wave elastography (SWE) is a highly reproducible method for measuring the propagation speed of shear waves within tissues to locally quantify tissue stiffness in kilopascals (kPa) or meters per second[4]. Three-dimensional (3D) SWE has also recently been developed. This method can provide 3D color-coded elasticity maps of tissue stiffness and quantitative 3D elastography volume images in a single acquisition[5].

Moreover, elastography has recently been shown to be useful for monitoring the effects of ablative therapies on tumors. Early investigations at other laboratories as well as a number of clinical studies suggest that US elastography may be superior to conventional US for monitoring the lesions created by RF ablation[6]. If this is found to be the case, US elastography may prove to be a more useful method for precisely assessing ablated areas. As additional advantages, the administration of contrast agent is not required and real-time observation is possible.

The goal of the present study was to investigate in detail how closely the boundaries of thermal lesions observed by 3D SWE correspond to the actual boundaries of tissue ablation determined by histopathological examination. Specifically, we first determined a threshold kPa value that is correlated with the presence of viable cells indentified in histopathological specimens. Next, based on this threshold value, we compared the volumes of the thermal lesions depicted by 3D SWE with those estimated by gross pathological examination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The Animal Care and Use Committee of Tokyo Medical University (TMU) approved the use of animals in this study. Ten male Wistar rats weighing 300-400 g at the time of purchase were studied. All rats received appropriate care from properly trained professional staff in compliance with both the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of TMU.

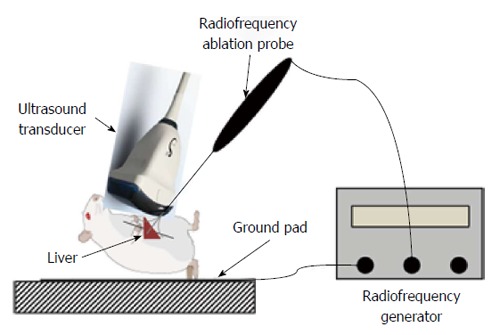

Before RF ablation, the rats were anesthetized by the intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (10 mg/kg body weight). The liver was accessed via open laparotomy with packing to ensure adequate hepatic exposure. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup employed in this study. Radiofrequency ablation of the liver was performed in 10 rats under laparotomy.

RF ablation system

An electrosurgical device (RITA Medical Inc., Mountain View, CA, United States) was used for the RF ablation procedures. The RF ablation electrode of this device consists of a 15-gauge shaft through which multiple sharp tines, each with a diameter of 0.053 cm (0.021 inches, 25 gauge), can be deployed. Fully extended, the tines assume an “umbrella” configuration with the tines spaced at 45º intervals. The electrode was inserted into the liver to a depth of 5 mm and the tines were then deployed, taking care to ensure that the tines remained within the liver parenchyma. RF ablation of the target tissue was performed for 3 min, with the tissue heated to a set temperature of 90 °C using a maximum power level of 10 W (Figure 1).

US examinations

US examinations were performed using an Aixplorer US system equipped with a 4-15-MHz linear-array transducer (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France) by one hepatologist with 10 years of experience in abdominal US. Fifteen minutes after RF ablation, 3D B-mode US and SWE were performed with a 5-16-MHz dedicated volume transducer. Volume imaging was automatically performed by slow-tilt movement of the mechanical sector transducer with a sweep angle of 30º. After the US examination was completed, the acquired 3D volume data were rendered and saved in the US system console as a multislice display (interslice distance: 1.10 mm) for off-line analysis, including ablation volume measurement.

Tissue collection and histological analysis

The animals were sacrificed after completion of the US examinations, and the livers were harvested. To permit radiologic-pathologic correlation, US was used to guide cutting of the livers in the proper sectional planes along the course of the ablation electrode. After formalin fixation, the livers were cut by total segmentation and digitized photographs of the cut surfaces were obtained. The photographs were used to estimate the volume of the 10 thermal lesions. For histopathological examination, the liver specimens were embedded in paraffin and cut with a microtome to obtain 3-μm sections. The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) or an anti-heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) antibody (sc-24; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

SWE and pathological volume measurements

The estimated volumes of the 10 thermal lesions were used to assess the correlation between SWE findings and the digitized photographs of the gross pathological specimens. The estimated volume of each lesion in the gross pathological specimens was calculated by summing the values obtained by multiplying the area of the thermal lesion in each section by the section thickness (3 mm). For SWE, the volume of each lesion was automatically calculated by summing the values obtained by multiplying the area of the thermal lesion in each 2D SWE image by the scan plane interval (1.10 mm). All RF ablation areas in the SWE images as well as in the digitized photographs of the gross pathological sections were manually delineated based on the consensus of two observers.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. The differences in the detectability of RF ablation lesion boundaries between SWE and B-mode US imaging were evaluated using the McNemar test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between the groups. The accuracy of the various volume measurements was compared with the reference standard (pathological findings) using multiple linear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 11.0 computer software package (SPSS, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

US findings after RF ablation

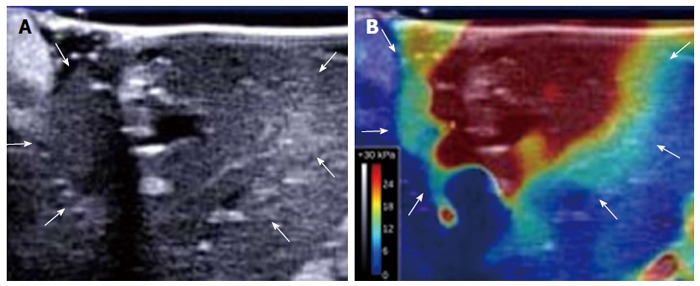

For each SWE image, the tissue stiffness of each pixel was displayed as a semitransparent color overlay with a range from dark blue, indicating the lowest stiffness (just over 0 kPa), to red, indicating the highest stiffness (set at 30 kPa). SWE images after RF ablation clearly delineated the ablated area, which is seen as a red area surrounded by a yellow-green area (Figure 2B). The surrounding yellow-green area, which exhibited sinusoidal dilatation accompanied by congestion in the H-E sections, was observed in all RF-ablated lesions. On the other hand, B-mode US after RF ablation showed a poorly defined hypoechoic lesion with a hyperechoic rim (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

B-mode ultrasound image and shear-wave elastography image of a thermal lesion. A: B-mode ultrasound image of the liver obtained 15 min after ablation shows a poorly defined hypoechoic lesion with a hyperechoic rim (arrows); B: Corresponding shear-wave elastography image of the liver clearly delineates the ablated area (arrows).

All RF ablation areas in the maximal plane of the SWE images as well as in the B-mode images were manually delineated based on the consensus of two observers. Table 1 shows a comparison of the detectability of RF ablation lesion boundaries between SWE and B-mode images. The boundaries of all 10 thermal lesions (100%) were completely delineated by SWE, while only 3 lesions (30%) could be completely delineated in the B-mode images. The other 7 lesions (70%) could only be partially delineated in the B-mode images. The difference in lesion detectability between the two techniques was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Boundary detection of thermal lesions using B-mode ultrasound and shear wave elastography n (%)

| Boundary detection | B-mode (n = 10) | SWE (n = 10) |

| Complete | 3 (30) | 10 (100) |

| Partial | 7 (70) | 0 (0) |

All radiofrequency (RF) ablation lesions visualized by shear-wave elastography (SWE) and B-mode ultrasound were manually delineated based on the consensus of two observers. Complete: Complete delineation of RF ablation lesion boundaries; Partial: Partial delineation of RF ablation lesion boundaries.

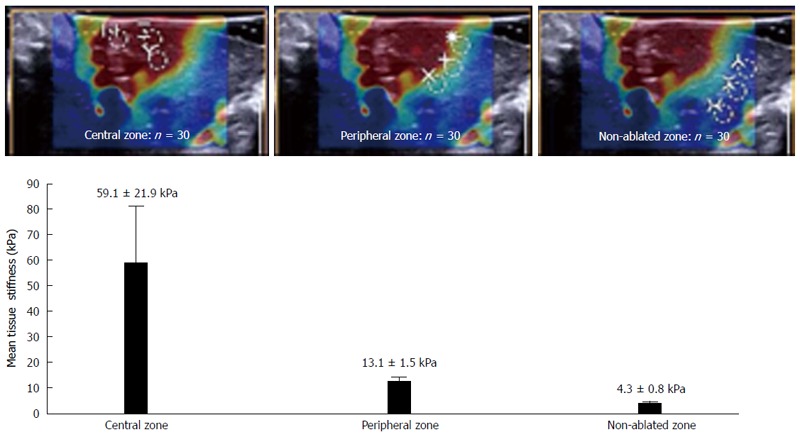

In each shear-wave image of the RF ablation area, circular regions of interest (ROIs) measuring 3 mm in diameter were specified in the central red zone, the surrounding yellow-green zone, and the non-ablated zone (3 ROIs in each zone). The mean tissue stiffness values of the central zone, the peripheral zone, and the non-ablated zone were 59.1 ± 21.9 kPa, 13.1 ± 1.5 kPa, and 4.3 ± 0.8 kPa, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Liver tissue stiffness values of the thermal lesions. Mean tissue stiffness of the central zone, peripheral zone, and non-ablated zone of the livers after radiofrequency ablation. The images at the top show examples of how the regions of interest in each zone were selected.

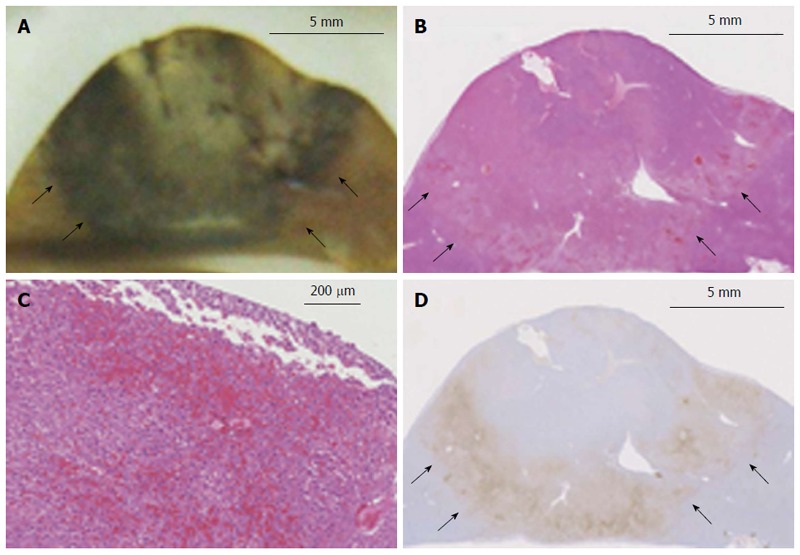

Pathological findings after RF ablation

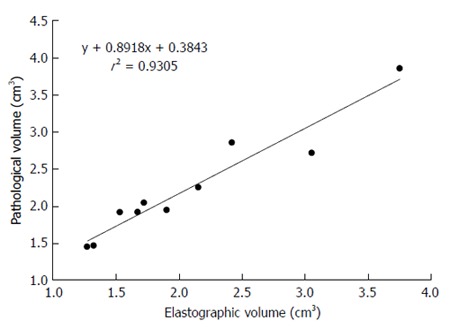

In the gross pathological specimens, the regions affected by RF ablation could be easily distinguished from unaffected liver tissue based on their colors after formalin fixation. The heat-coagulated lesions appeared light tan to gray and were consistently observed to have a dark brown rim of vascular congestion (Figure 4A). These gross pathological changes correlated well with the histopathological findings. Specifically, the rim of vascular congestion identified by gross pathological examination was histopathologically characterized by sinusoidal dilatation, hemostasis, hemorrhage, and overexpression of Hsp70 in hepatocytes, which accurately discriminated the heat-coagulated lesions from the unaffected normal liver tissue in all samples (n = 10) (Figure 4B, C, and D). A high correlation was observed between the volumes depicted by SWE and those estimated by gross pathological examination (r2 = 0.9305) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Histopathological findings of a thermal lesion. A: Gross pathological examination of a radiofrequency (RF)-ablated liver shows a core area of white coagulation and a surrounding dark rim of hemorrhagic tissue (arrows). Scale bar: 5 mm; B, C: H-E staining of an RF-ablated liver shows a hemorrhagic rim surrounding the ablated area (arrows), with sinusoidal dilatation and congestion associated with cellular dissociation. Scale bar in (B): 5 mm, and in (C): 200 μm; D: Hsp70 staining of the hemorrhagic rim in (B) shows a clearly demarcated band of Hsp70 expression (arrows), which is suggestive of the presence of thermally damaged cells within the rim. Scale bar: 5 mm.

Figure 5.

Correlation between shear-wave elastography and gross pathological findings. The correlation between the volume of liver ablation depicted by 3D shear-wave elastography and that estimated by gross pathological examination was 0.9305, which is highly significant.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study using normal rat livers demonstrate that the depiction of thermal lesions by SWE agrees closely with the findings of gross pathological examination. SWE is therefore expected to be useful for clearly visualizing thermal lesions and obtaining quantitative volume estimates. Comparison between the ablation volumes depicted by SWE and those estimated by gross pathological examination showed a high correlation (r2 = 0.9305). These findings suggest that 3D SWE may prove to be an accurate and convenient tool for monitoring early treatment effects after RF ablation.

At present, contrast-enhanced US[7], contrast-enhanced computed tomography[8], and magnetic resonance imaging[9] are considered to be suitable methods for depicting ablation zones by demonstrating the absence of contrast enhancement when performed at an appropriate time after the ablation procedure. However, in order to perform virtual real-time monitoring of an ablation procedure, repeated contrast injection is required because there is only a short time frame in which the lesion is detectable before equilibrium is reached. These modalities are therefore unsuitable for real-time monitoring during RF ablation procedures, making it difficult to precisely evaluate the ablation zone at the time of treatment. Moreover, an enhanced rim is usually observed in contrast images, which may be difficult to differentiate from an enhanced rim indicating an area of residual untreated tumor. For these reasons, SWE may prove to be a more useful method for real-time monitoring in RF ablation procedures.

The H-E staining technique relies on visual examination of the cell membranes and intracellular structures to assess cell viability. Morimoto et al[8] have shown that H-E staining provides inconsistent results regarding the extent, or completeness, of tissue necrosis when performed less than 24 h after the application of the necrosis-inducing agent. Therefore, histochemical staining methods, such as those employing lactate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) diaphorase, are thought to be superior to H-E staining for identifying irreversible cellular damage after RF ablation. Accordingly, Morimoto et al[8] also evaluated heat-coagulated lesions after RF ablation by analyzing cell viability within the lesions using histochemical staining (lactate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase, and NADPH diaphorase). They found that the regions of heat coagulation (i.e., the central areas of the ablated lesions) were not stained in any of the samples, suggesting 100% cellular destruction within the lesion. Moreover, the surrounding hemorrhagic rim (i.e., the peripheral part of the ablated lesion) was also not histochemically stained in any of the samples, suggesting the disappearance of viable cells from the rim as well. Based on these findings, we also assumed that viable cells were absent from the surrounding narrow rim of vascular congestion observed in our study. Interestingly, a thick rim of Hsp70 staining, which is a marker of thermal damage, was noted in the area peripheral to the ablation zone, which corresponded to the congestive rim. Hsp70 may therefore be a useful biomarker for assessing cell viability after thermal damage[10].

In our study, the mean tissue stiffness of the hemorrhagic rim was 13.1 ± 1.5 kPa, and our findings suggest that this may be an appropriate threshold value for determining irreversible cellular destruction. This value may also be of clinical significance because an incompletely ablated area should be softer (i.e., less than 13.1 kPa) and show higher contrast than surrounding completely ablated areas, which may provide useful information for guiding a second round of RF ablation to treat the incompletely ablated area.

It should be noted that our study suffers from a number of limitations. First, the study was performed in normal rat livers. Similar studies should be performed in a liver tumor model or in cirrhotic livers to increase the clinical relevance of the findings. Second, cell viability was assessed only by H-E staining and by immunohistochemical analysis of Hsp70. Assessment of cell viability using more reliable methods should be performed in future studies. Third, at present, contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are considered to be suitable methods for depicting ablation zones by demonstrating the absence of contrast enhancement, but we did not compare SWE against these modalities in our study. Nevertheless, SWE has been shown to be an effective, safe, and cost-efficient tool for evaluating tumor treatment in the interventional suite immediately after ablation.

In conclusion, 3D SWE is a reliable noninvasive technique that may allow the real-time assessment of treatment efficacy immediately after RF ablation procedures. The threshold value for determining remaining cell viability was found to be 13.1 ± 1.5 kPa.

COMMENTS

Background

The ability to assess the completeness of radiofrequency (RF) ablation during or immediately after the procedure would be of great clinical value. If three-dimensional (3D) shear-wave elastography (SWE) is found to be superior for precise assessment of the ablation area, it would be a better method for assessing the completeness of RF ablation because the administration of contrast agent is not required and both 3D assessment and real-time observation are possible.

Research frontiers

To the best of our knowledge, no other investigators have reported on the usefulness of 3D SWE for evaluation of the ablated area after RF ablation procedures.

Innovations and breakthroughs

3D SWE is a reliable noninvasive technique that may allow the real-time assessment of treatment efficacy immediately after RF ablation procedures. It is superior to B-mode ultrasound (US) in delineating ablated areas in the liver.

Applications

By providing a clearer understanding of how closely the boundaries of thermal lesions visualized by 3D SWE correspond to the actual boundaries of tissue ablation determined by histological examination, this study may lead to improved local ablation therapy in patients with hepatic malignancies.

Terminology

Among the various techniques employed in US elastography, SWE is a highly reproducible method that allows measurement of the propagation speed of shear waves within tissues for the local quantification of tissue stiffness in kilopascals or meters per second.

Peer review

The manuscript titled “Radiologic-pathologic correlation of three-dimensional shear-wave elastographic findings after radiofrequency ablation” regards the evaluation of RF ablation with the SWE compared to simple B mode, which is a generally well-written paper focused on an important topic.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Rossi RE, Ruzzenente A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Livraghi T, Goldberg SN, Lazzaroni S, Meloni F, Solbiati L, Gazelle GS. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with radio-frequency ablation versus ethanol injection. Radiology. 1999;210:655–661. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99fe40655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, Asaoka Y, Sato T, Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:569–577; quiz 578. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, Wu H, Du L, Wang J, Xu Y, Zeng Y. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg. 2010;252:903–912. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181efc656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraioli G, Tinelli C, Dal Bello B, Zicchetti M, Filice G, Filice C. Accuracy of real-time shear wave elastography for assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: a pilot study. Hepatology. 2012;56:2125–2133. doi: 10.1002/hep.25936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youk JH, Gweon HM, Son EJ, Chung J, Kim JA, Kim EK. Three-dimensional shear-wave elastography for differentiating benign and malignant breast lesions: comparison with two-dimensional shear-wave elastography. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1519–1527. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2736-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolokythas O, Gauthier T, Fernandez AT, Xie H, Timm BA, Cuevas C, Dighe MK, Mitsumori LM, Bruce MF, Herzka DA, et al. Ultrasound-based elastography: a novel approach to assess radio frequency ablation of liver masses performed with expandable ablation probes: a feasibility study. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:935–946. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue T, Kudo M, Hatanaka K, Arizumi T, Takita M, Kitai S, Yada N, Hagiwara S, Minami Y, Sakurai T, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography to evaluate the post-treatment responses of radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with dynamic CT. Oncology. 2013;84 Suppl 1:51–57. doi: 10.1159/000345890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto M, Sugimori K, Shirato K, Kokawa A, Tomita N, Saito T, Tanaka N, Nozawa A, Hara M, Sekihara H, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with radiofrequency ablation: radiologic-histologic correlation during follow-up periods. Hepatology. 2002;35:1467–1475. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koda M, Tokunaga S, Miyoshi K, Kishina M, Fujise Y, Kato J, Matono T, Okamoto K, Murawaki Y, Kakite S. Assessment of ablative margin by unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging after radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2730–2736. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faroja M, Ahmed M, Appelbaum L, Ben-David E, Moussa M, Sosna J, Nissenbaum I, Goldberg SN. Irreversible electroporation ablation: is all the damage nonthermal? Radiology. 2013;266:462–470. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]