Abstract

Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of the gallbladder is a rare subtype of gallbladder tumor. Here, we report two cases of NEC in two patients initially suspected to have gallbladder carcinoma. No specific symptoms or abnormal blood test results were observed preoperatively. Abdominal computed tomography scans indicated intraluminal masses in the gallbladder and lymph node enlargement in the hepatic hilum. Radical cholecystectomy and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. The first patient also presented with liver invasion and therefore underwent resection of liver segment IV. A diagnosis of NEC was made upon postoperative pathological examination and immunohistochemical staining according to the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System (2010). One tumor was identified as poorly differentiated NEC and the other as poorly differentiated mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining data from both tumors showed positivity for chromogranin A and synaptophysin. The first patient received 4 cycles of chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and etoposide. No metastases or recurrence were observed 12 mo following surgery. The second patient refused chemotherapy and presented with tumor recurrence 4 mo after surgery. In conclusion, NEC of the gallbladder is an aggressive tumor and the identification of a standardized optimal treatment still requires further research. Our experience together with published studies suggests that radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy may improve the prognosis.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine carcinoma, Tumor, Gallbladder, Chemotherapy, Carcinoid

Core tip: The authors report two cases of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder, which is an extremely rare disease. Both patients received radical surgery and showed responses to chemotherapy. The authors discuss possible approaches to improving prognosis including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and biological targeted therapy in the context of their experience and previously published studies.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are neoplasms originating from neuroendocrine cells located throughout the body, most commonly in the lung and gastrointestinal tract[1,2]. NETs are generally subclassified by site of origin and histological characteristics including tumor differentiation and grade. Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) often refers to tumors with poor differentiation and high grade. Well differentiated tumors are defined as carcinoid and can further be divided into typical and atypical, based on the grade or biological behavior[3]. NETs of the gallbladder are rare and account for only 0.5% of all NETs[4] and 2% of all gallbladder tumors, as reported by Yao et al[2]. Among 278 cases of NETs of the gallbladder reported in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, only five well-differentiated NETs were registered[5]. Almost all patients with NEC of the gallbladder are diagnosed incidentally on the basis of pathological examination and postoperative immunohistochemical staining[6]. Because of the relative paucity of cases, the clinicopathological characteristics and prognoses for NEC of the gallbladder remain largely undetermined. Here we report two cases of gallbladder tumor, one case of NEC and one of mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC). Both patients underwent radical surgery and showed good responses to chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and etoposide.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

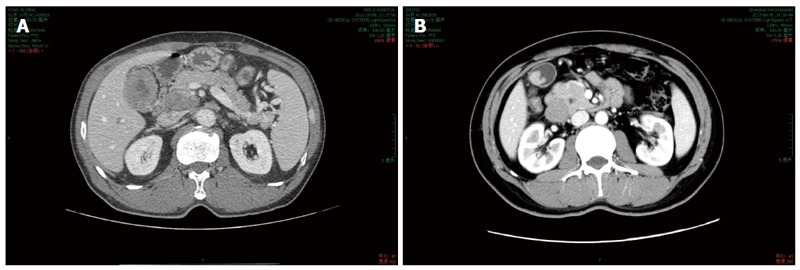

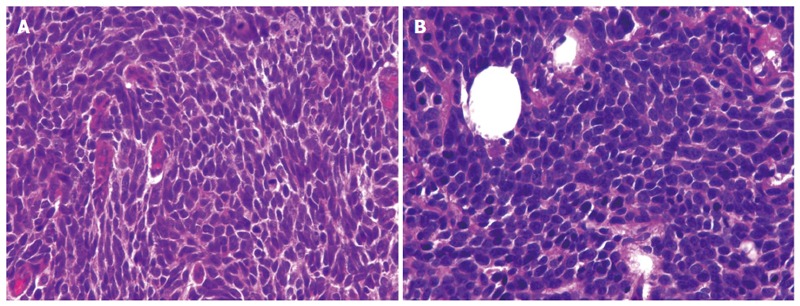

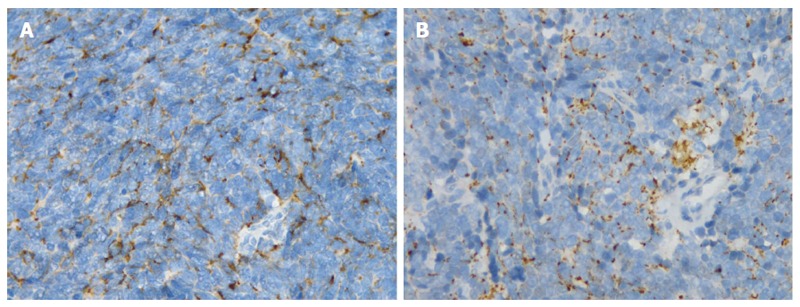

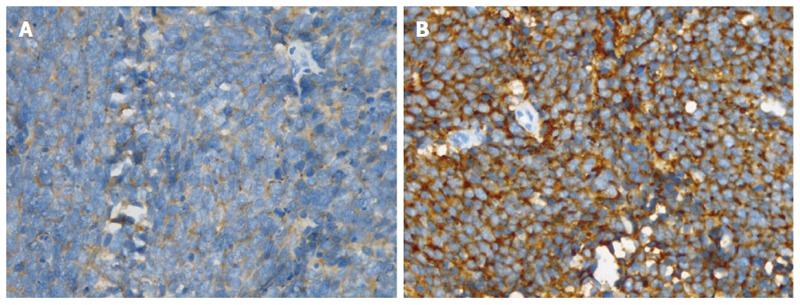

A 62 year-old male presented to our hospital with a history of nausea and vomiting for 2 wk. He had no abdominal pain, jaundice, weight loss or other complaints. The physical examination was normal. Full blood count, renal and liver function tests were within normal ranges. Because of vomiting, his serum sodium and chlorine concentrations were moderately decreased to 122 mmol/L and 85 mmol/L, respectively. Levels of tumor markers were as follows: AFP 2.88 ng/mL (normal range 0-7 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 81.23 μg/L (normal range 0-4.8 μg/L), 19-9 carbohydrate antigen (CA19-9) 31.52 μg/mL (normal range 0-33 μg/mL). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) depicted a thick-walled gallbladder with local infiltration to the adjacent liver and no gallstones (Figure 1A). There were no signs of distal metastases in CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. The patient had a 3 year history of hypertension and denied any family history of cancer. He had undergone appendectomy 12 years before and endoscopicpolypectomy of the colon 2 years before. A solid mass of 4 cm × 4 cm × 2.5 cm in size was found in the body of the gallbladder, infiltrating the liver parenchyma for about 1 cm. En bloc cholecystectomy, resection of liver segment IV and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. Postoperative pathological findings (Figure 2A) were poorly differentiated NEC with serosal invasion and liver invasion. Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of chromogranin A (CGA) (Figure 3A), synaptophysin (SYN) (Figure 4A), cytokeratin (CK) and cluster of differentiation (CD) 56. Furthermore, the Ki-67 index was over 80%. The level of CEA decreased to the normal range one week after surgery and the levels of other tumor makers were maintained within normal ranges. The patient made an uneventful recovery and received combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide. The regimen consisted of cisplatin 25 mg/m2 given intravenously on days 1-3 and etoposide 120 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1-3, repeated every 4 wk. After 4 cycles of this regimen, treatment was discontinued due to serious neutropenia. Twelve months following surgery, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was normal and levels of tumor markers were well within normal ranges.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of the gallbladder carcinoma. A: A thick-walled gallbladder with local infiltration to the adjacent liver; B: A polypoid intra-luminal lesion about 4 cm in diameter.

Figure 2.

Pathological examination, HE, × 400. A: Postoperative pathological findings were poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with serosal invasion and liver invasion; B: No transitional areas were observed between the two different parts.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for chromogranin A. A: Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of chromogranin A (CGA); B: Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for CGA.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin. A: Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of synaptophysin (SYN); B: Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for SYN.

Case 2

A 34 year-old male presented to our hospital with a history of dull pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen for over 2 mo. There was no relationship between the pain and eating. The patient had no symptoms of dyspepsia or jaundice and the physical examination was normal. Full blood count, urea analysis, liver function tests and levels of tumor markers were within normal ranges. Two hyperecho masses in the gallbladder (27 mm × 14 mm, 31 mm × 16 mm) and dilation of the portal vein and common bile duct were revealed by abdominal ultrasonography. No stones were detected in the gallbladder. A CT scan of the abdomen revealed a polypoid intra-luminal lesion about 4 cm in diameter within the gallbladder and lymph node enlargement around the hepatic hilum and pancreas (Figure 1B). En bloc cholecystectomy and lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilum and pancreas were performed. No distal metastasis or ascites was observed during the operation. Postoperative pathological findings showed MANEC of the gallbladder with serosal and lymph nodes invasion. No transitional areas were observed between the two different parts (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for CGA (Figure 3B), SYN (Figure 4B), CD56, HER2, CK and mucin (MUC) 1. Furthermore, the Ki-67 index was over 50%. The patient was discharged without complications, but he refused adjuvant chemotherapy. He returned 4 mo later, presenting with back pain. An abdominal CT scan showed lymph node enlargement in the retroperitoneum and hepatic hilum. Intraarterial chemotherapy was performed and the pain was relieved. The patient is now receiving the first cycle of chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and etoposide.

DISCUSSION

NETs are classified into three broad histological categories based on tumor differentiation and grade according to the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System in 2010: well-differentiated, low-grade (G1); well-differentiated, intermediate-grade (G2); and poorly differentiated, high-grade (G3). Tumor differentiation and grade often correlate with mitotic count and Ki-67 proliferation index. NETs are staged according to the AJCC tumor (T), node (N) and metastasis (M) staging system. Carcinoids of the stomach, duodenum/ampulla/jejunum/ileum, colon/rectum, and appendix have separate staging systems, but NETs of the gallbladder do not[7].

NEC is frequently combined with other histological carcinoma elements, such as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. MANEC is diagnosed only when both portions are more than 30% in the pathological examination[8].

The clinical presentations of most patients are non-specific, and vague abdominal pain is the most common initial symptom[9]. Radiological tests including ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging and PET-CT can reveal gallbladder masses indicative of gallbladder cancer. It is almost impossible, however, to preoperatively differentiate the NEC from other subtypes of gallbladder carcinomas. Pathological examination and immunohistochemical staining such as for CGA and SYN are required for the diagnosis of NEC.

As with other gallbladder carcinomas, NEC can readily invade the adjacent liver parenchyma and later cause biliary obstruction, making it challenging to detect at an early stage. Due to the aggressiveness of the tumor and lack of early symptoms, patients are often diagnosed at an advanced stage with lymph node invasion or liver invasion, and accordingly have a poor prognosis[5,10]. Both of the two patients in our report had no hormone-related symptoms, such as diarrhea, flushing or hyperglycaemia. Previous reports show that most NETs of the gallbladder had no carcinoid syndrome[11]. The proportion of carcinoid, which should be classified as well differentiated and lower grade neuroendocrine tumor, is much lower in the gallbladder than any other site in the gastrointestinal system. This may be another factor which contributes to the poor prognosis of NET of the gallbladder.

If the gallbladder specimen reveals only mucosal involvement on microscopic examination (Tis), or a pathologic report returns with identification of an incidental cancer with only submucosal or muscular invasion (T1), a simple cholecystectomy is adequate[12]. But for patients in advanced stages without distal metastasis, radical cholecystectomy and lymphadenectomy combined with hepatic resection should be performed to obtain adequate margins[5]. Improved outcomes have been realized with aggressive radical operative therapy in gallbladder carcinoma, and some reports have shown that patients with a locally invasive NEC of the gallbladder may benefit from aggressive surgical treatment, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy[13]. In patients with unresectable tumors, systemic chemotherapy is the treatment of choice[14].

Until now, there has been no standard indication for adjuvant therapy in patients with biliary neuroendocrine tumor and decisions on adjuvant therapy were made on the basis of clinical situations such as dissemination state, resection margin and histological classification[9].

For patients with poorly differentiated NEC, cisplatin or carboplatin and etoposide are generally recommended as the primary treatment, representing one of the standard regimens employed for the treatment of small cell lung cancer[15]. Iwasa et al[15] concluded that the use of the cisplatin and etoposide combination as a first-line chemotherapy for hepatobiliary or pancreatic poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma had only marginal antitumor activity and relatively severe toxicity compared with previous studies on extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma treated with the same regimen. Evolving data suggest that patients with small cells or extremely high Ki-67 index have a better response. Iype collected 29 cases of poorly differentiated NEC and concluded that the large-cell subtype had a worse prognosis than the small-cell variety and chemotherapy was more effective for the small-cell subtype[16]. Other regimens have also proved to be effective for NEC of the gallbladder. Taniguchi et al[17] reported a case of adenoendocrine cell carcinoma of the gallbladder which exhibited a partial response to the combined use of docetaxel and cisplatin, following the emergence of gemcitabine resistance.

Shimono et al[18] reported one case of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder in a 64-year-old woman who survived for 69 mo after the initial diagnosis due to the use of multimodal treatment, consisting of intraarterial chemotherapy, three-dimensional radiation therapy, right trisegmentectomy, and γ-knife irradiation (for brain metastases). This result proves that radiation therapy can be a useful modality for neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy in achieving local control.

Biological targeted therapies (like SST analogs) have proved effective in controlling symptoms in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs)[19]. Unfortunately however, no similar cases for the gallbladder have been reported to date.

With regard to prognosis, tumor invasion of adjacent structures is an important negative predictor of outcome, compared to the presence of localized gallbladder wall tumors which show better prognosis[8,20]. Evidence of elevated Ki67 and high mitotic index is also likely to be predictive of poor outcome much as has been described in other NETs[5].

In conclusion, NEC of the gallbladder is a rare subtype of gallbladder tumor with aggressive behavior and poor prognosis. Radical surgery, including en bloc cholecystectomy and lymphadenectomy combined with hepatic resection plus adjuvant chemotherapy are recommended for patients in advanced stages without distal metastasis. Radiotherapy should be considered to control local recurrence or metastasis. The standardization of treatment including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and biological targeted therapy still requires further investigations.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

The two patients presented with non-specific symptoms including nausea, vomiting and dull pain.

Clinical diagnosis

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder.

Differential diagnosis

Pathological examination and immunohistochemical staining for chromogranin A (CGA) and synaptophysin (SYN) are the major methods for differential diagnosis.

Laboratory diagnosis

Preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was elevated in one patient.

Imaging diagnosis

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a gallbladder with thickened wall or an intra-luminal mass.

Pathological diagnosis

Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of CGA and SYN.

Treatment

Both patients underwent radical surgery and chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and etoposide.

Experiences and lessons

Radical surgery including en bloc cholecystectomy and lymphadenectomy, combined with hepatic resection plus adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for patients in advanced stages without distal metastasis.

Peer review

The study is a very interesting report on 2 rare cases of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder. The authors recommend radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy based on their experiences and previously published data. Immunohistochemical staining (e.g., for pancreatic polypeptide and somatostatin) should be given more attention.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Portela-Gomes G, Zhang LH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Waldum HL, Drozdov I, Chan AK, Modlin IM. Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America. Cancer. 2008;113:2655–2664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosman FT, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishigami T, Yamada M, Nakasho K, Yamamura M, Satomi M, Uematsu K, Ri G, Mizuta T, Fukumoto H. Carcinoid tumor of the gall bladder. Intern Med. 1996;35:953–956. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.35.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eltawil KM, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Modlin IM. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: an evaluation and reassessment of management strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;44:687–695. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d7a6d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mezi S, Petrozza V, Schillaci O, La Torre V, Cimadon B, Leopizzi M, Orsi E, La Torre F. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:334. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edge SB, American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging handbook: from the AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. p. 649. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deehan DJ, Heys SD, Kernohan N, Eremin O. Carcinoid tumour of the gall bladder: two case reports and a review of published works. Gut. 1993;34:1274–1276. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.9.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Lee WJ, Lee SH, Lee KB, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Kim SW, Yoon YB, Hwang JH, Han HS, et al. Clinical features of 20 patients with curatively resected biliary neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Hossain S, Henson DE, Schwartz AM. Carcinoid tumors and small-cell carcinomas of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts: a comparative study based on 221 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou YP, Li WM, Liu HR, Li N. Primary carcinoid tumor of the gallbladder: a case report and brief review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Donohue JH. Diagnosis and surgical management of gallbladder cancer: a review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DI, Seo HI, Lee JY, Kim HS, Han KT. Curative resection of combined neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Tumori. 2011;97:815–818. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuyama Y, Fukui A, Enoki Y, Morishita H, Yoshida N, Fujimoto S. A large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gall bladder: diagnosis with 18FDG-PET/CT-guided biliary cytology and treatment with combined chemotherapy achieved a long-term stable condition. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:571–574. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwasa S, Morizane C, Okusaka T, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Kondo S, Tanaka T, Nakachi K, Mitsunaga S, Kojima Y, et al. Cisplatin and etoposide as first-line chemotherapy for poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the hepatobiliary tract and pancreas. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:313–318. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iype S, Mirza TA, Propper DJ, Bhattacharya S, Feakins RM, Kocher HM. Neuroendocrine tumours of the gallbladder: three cases and a review of the literature. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:213–218. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.070649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taniguchi H, Sakagami J, Suzuki N, Hasegawa H, Shinoda M, Tosa M, Baba T, Yasuda H, Kataoka K, Yoshikawa T. Adenoendocrine cell carcinoma of the gallbladder clinically mimicking squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:167–170. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimono C, Suwa K, Sato M, Shirai S, Yamada K, Nakamura Y, Makuuchi M. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder: long survival achieved by multimodal treatment. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:351–355. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikou GC, Lygidakis NJ, Toubanakis C, Pavlatos S, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Giannatou E, Mallas E, Safioleas M. Current diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal carcinoids in a series of 101 patients: the significance of serum chromogranin-A, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and somatostatin analogues. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:731–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter JM, Kalloo AN, Abernathy EC, Yeo CJ. Carcinoid tumor of the gallbladder: laparoscopic resection and review of the literature. Surgery. 1992;112:100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]