Abstract

Introduction:

Lower concentrations of serum bilirubin, an endogenous antioxidant, have been associated with risk of many smoking-related diseases, including lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, and current smokers are reported to have lower bilirubin levels than nonsmokers and past smokers. This study evaluates the effects of smoking cessation on bilirubin levels.

Methods:

In a secondary analysis of a 6-week placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation, indirect and total bilirubin concentrations were evaluated at baseline and following smoking cessation. Individuals who were continuously abstinent for 6 weeks (n = 155) were compared to those who were not (n = 193). Participants reported smoking ≥20 cigarettes daily at baseline and received smoking cessation counseling, 21mg nicotine patch daily, and either placebo or 1 of 3 doses of naltrexone (25, 50, or 100mg) for 6 weeks. Change in indirect and total bilirubin following the quit date was measured at Weeks 1, 4, and 6 compared to baseline.

Results:

Individuals who were continuously abstinent from smoking, independent of naltrexone condition, showed a significantly greater mean increase in indirect (~unconjugated) bilirubin (0.06mg/dl, SD = 0.165) compared to those who did not (mean = 0.02, SD = 0.148, p = .015). Similar results were obtained for total bilirubin (p = .037).

Conclusions:

Smoking cessation is followed by increases in bilirubin concentration that have been associated with lower risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.

INTRODUCTION

Although it is widely known that unconjugated bilirubin can be elevated in hemolytic diseases and can be neurotoxic at very high levels in newborns (Watchko & Tiribelli, 2013), unconjugated bilirubin, the primary form of bilirubin circulating in healthy individuals, is also a powerful antioxidant (Rizzo et al., 2010; Stocker, Yamamoto, McDonagh, Glazer, & Ames, 1987) at levels within the normal reference range. Thus, while seemingly counterintuitive, bilirubin has been inversely associated with risk of a number of disorders, including pulmonary disease (Horsfall et al., 2011), cardiovascular disease (Hopkins et al., 1996; Madhavan, Wattigney, Srinivasan, & Berenson, 1997), diabetes (Cheriyath et al., 2010), rheumatoid arthritis (Fischman et al., 2010), colon cancer risk (Zucker, Horn, & Sherman, 2004), and all-cause and cancer mortality (Temme, Zhang, Schouten, & Kesteloot, 2001). Of note, bilirubin concentrations recently emerged from metabolic profiling as the strongest predictor of lung cancer risk in smokers following a multiphase validation study (Zhang et al., 2013).

The concordance between the negative health consequences of smoking, including those recently highlighted by the Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014) and those associated with lower bilirubin concentrations, is striking. Numerous studies have found that smokers have lower bilirubin levels than nonsmokers (Hopkins et al., 1996; Madhavan et al., 1997; Merz, Seiberling, & Thomann, 1998; Van Hoydonck, Temme, & Schouten, 2001; Zucker et al., 2004). The possibility that smoking leads to reductions in bilirubin, which in turn may contribute to smoking-related disease though diminished availability of this endogenous antioxidant, is intriguing. One possible mechanism for bilirubin reduction among smokers that has been suggested (van der Bol et al., 2007), but not proven (Zevin & Benowitz, 1999), is that of induction of UGT 1A1 by nicotine and/or other constituents of tobacco smoke. UGT 1A1 is the uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform, which catalyzes conjugation of bilirubin, the major metabolic pathway responsible for its disposition. A report of reduced toxicity of the chemotherapeutic agent irinotecan in smokers, in association with reduced concentrations of its active metabolite, SN-38 (Benowitz, 2007; van der Bol et al., 2007), provides conceptual support for this mechanism. The disposition of irinotecan’s active metabolite is, like bilirubin, mediated by UGT 1A1. With smoking cessation, enzyme induction may dissipate leading to increase in bilirubin concentrations.

Considering the established link between bilirubin levels and health, modest increases in bilirubin within the reference range following smoking cessation may contribute to some of the health benefits of quitting smoking, possibly through its documented antioxidant effects. Epidemiological studies have found that past smokers have higher bilirubin concentrations than current smokers (Jo, Kimm, Yun, Lee, & Jee, 2012; Schwertner, 1998; Van Hoydonck et al., 2001), suggesting that smoking cessation may lead to increases in bilirubin. Despite this provocative finding, no one has yet examined the temporal relationship between smoking cessation and changes in bilirubin in a longitudinal analysis.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that smoking cessation leads to increases in bilirubin. Specifically, we compared change in bilirubin concentration for smokers who successfully quit smoking for 6 weeks to those who failed to maintain abstinence in a secondary analysis of a clinical trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation (O’Malley et al., 2006).

METHODS

Participants

Smokers were identified from a large placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation (O’Malley et al., 2006). Three hundred and eighty-five participants who reported smoking at least 20 cigarettes daily with an expired carbon monoxide (CO) > 10 ppm were enrolled and provided data post-randomization. The 348 individuals who at baseline had total bilirubin within the reference range (≤1.2mg/dl) and data on both total and indirect bilirubin at baseline and during treatment are the subject of these analyses.

Participants were enrolled between November 2000 and April 2003. The Institutional Review Boards of Yale University, the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, and University of Connecticut approved the study, and participants gave written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included significantly elevated serum aminotransferase activities; current serious neurological, psychiatric, or medical illness; current substance use disorder excluding nicotine dependence; and history of opiate dependence or current use. Women who were pregnant, nursing, or unwilling to use reliable contraception were excluded.

Procedures

Detailed methods are in the original report (O’Malley et al., 2006). As part of eligibility determination, participants received a physical examination and routine laboratory testing including serum bilirubin levels. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or three doses of naltrexone (25, 50, or 100mg daily) for 6 weeks; all received smoking cessation counseling and 21mg nicotine patch. At weekly appointments, smoking was assessed by self-report and expired CO. Blood samples were obtained for liver function tests, including bilirubin, at 1, 4, and 6 weeks following the quit date. Assays were performed by Quest Laboratories on the Beckman Coulter automated analyzer using a variation of the diazo reaction, with caffeine and a surfactant as accelerators for total bilirubin. Assay coefficients of variation for total and direct (~conjugated) bilirubin were 5.3% and 5.5%, respectively. Indirect (~unconjugated) bilirubin was computed as [total − direct bilirubin]; if total = direct (11 samples), indirect was set to 0.01.

Participants were classified as having quit smoking based on self-reported abstinence after the quit date, confirmed by expired CO levels < 10 ppm.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics, including bilirubin levels, were compared for those who were continuously abstinent (n = 155) and those who were not (n = 193) using chi-square tests or analysis of variance. Change in indirect (~unconjugated) bilirubin from baseline (e.g., Week X − baseline) was computed for Weeks 1, 4, and 6 and was compared using General Linear Mixed Models. The models included quit status, week (1, 4, 6), and the interaction of quit status and week. Medication condition and gender were included as covariates. Because epidemiological studies often report total bilirubin (the sum of direct plus indirect bilirubin), we also examined the effects of quitting on total bilirubin.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Quitters were older and had lower expired CO levels at baseline (Table 1). There were no differences in other baseline variables, including bilirubin and aspartate and alanine aminotransferase (AST and ALT) values. Although unable to maintain continuous abstinence for 6 weeks, the nonquitters showed substantial reductions in smoking. During treatment, they reported smoking 25% (SD = 30.94) of days with a mean of 3.6 (SD = 5.75) cigarettes/day compared to 26 at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Who Quit Smoking for 6 Weeks (Quit) Versus Those Who Did Not (Smoked)

| Variable | Quita (n = 155) | Smoked (n = 193) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 47.8 (10.62) | 45.1 (11.36) | .03 |

| Female, no. (%) | 74 (47.7) | 98 (50.8) | .57 |

| Race, White, no. (%) | 137 (88.4) | 167 (86.5) | .60 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 27.9 (4.57) | 27.7 (5.22) | .75 |

| Education, no. (%) | .35 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 52 (34.4) | 77 (42.1) | |

| Some college | 60 (39.7) | 66 (36.1) | |

| College graduate or more | 39 (25.8) | 40 (21.9) | |

| Cigarettes smoked/day, mean (SD) | 26.0 (8.56) | 26.9 (8.92) | .31 |

| Years smoking, mean (SD) | 30.5 (10.76) | 28.8 (10.94) | .16 |

| Expired CO, mean (SD), ppm | 23.5 (13.29) | 26.2 (10.49) | .03 |

| Serum cotinine, mean (SD), ng/ml | 301.8 (120.34) | 308.2 (119.51) | .63 |

| Percent days abstinent from alcohol, mean (SD) | 80.3 (27.66) | 80.4 (29.89) | .96 |

| Drinks per drinking day, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.85) | 1.9 (2.05) | .72 |

| Bilirubin total, mean (SD), mg/dlb | 0.45 (0.167) | 0.44 (0.164) | .67 |

| Bilirubin indirect (~unconjugated), mean (SD), mg/dlb | 0.29 (0.139) | 0.29 (0.132) | .66 |

| AST, mean (SD), units/Lc | 19.4 (7.47) | 19.2 (6.39) | .79 |

| ALT, mean (SD), units/Lc | 22.7 (15.96) | 20.4 (10.29) | .10 |

Note. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; CO = carbon monoxide.

aQuit status was defined by self-report of no smoking over 6 weeks of treatment and expired CO < 10 ppm.

bConversion factor to SI units = 17.1.

cConversion factor to SI units = 1.0.

Changes in Bilirubin Associated With Smoking Cessation

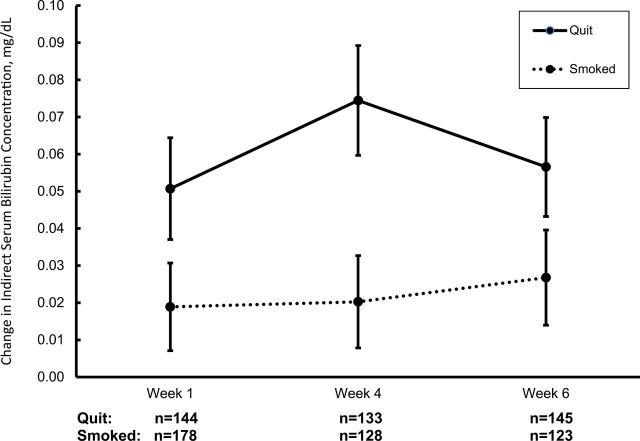

Quitting was a significant predictor of change of indirect (~unconjugated) bilirubin (F(1,342) = 6.01, p = .015). Individuals who were continuously abstinent had a greater average increase at all three timepoints (0.06mg/dl, SD = 0.165) than those who were not abstinent (0.02mg/dl, SD = 0.148). The change in indirect bilirubin from baseline was unrelated to week (p = .427), the interaction of quit status and week (p = .614), naltrexone condition (p = .267), or sex (p = .307). Adding the interaction of naltrexone and quit status (F(1,339) = 1.41, p = .239) did not modify the relationship between quit status and indirect bilirubin change. Change in total bilirubin showed similar findings to indirect bilirubin with quitting being significantly predictive (F(1,342) = 4.39, p = .037; mean change = 0.05mg/dl, SD = 0.181 for quitters and mean = 0.02, SD = 0.178 for nonquitters). Figure 1 presents the mean change in indirect bilirubin for quitters and nonquitters by week and illustrates that the increase in bilirubin occurred as early as 1 week after quitting. Multivariate adjustment for other baseline variables that differed between quitters and nonquitters did not alter the findings. Post-cessation changes in AST and ALT did not differ by quit status (p values > .65).

Figure 1.

Mean change in indirect (~unconjugated) bilirubin from baseline at Weeks 1, 4, and 6 by quit status. Means and standard errors by quit status and week. The main effect of quit status was significant (p = .015). The effect of week (p = .427) and the interaction of week and quit status (p = .614) were not significant.

DISCUSSION

Our data establish the temporal relationship between quitting smoking and increases in serum bilirubin concentrations using a longitudinal design. Increases of the magnitude observed (e.g., 0.06mg/dl), within normal levels of bilirubin (up to 1.2mg/dl), have been associated with clinical benefits. For example, a meta-analysis of the association of bilirubin and cardiovascular disease in men found that an increase of 0.06mg/dl was associated with a 6.5% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease (Novotny & Vitek, 2003). Similarly, a 0.1mg/dl increase in total bilirubin was associated with an 8% and an 11% decrease in lung cancer risk for men and women, respectively (Horsfall et al., 2011).

In our study, the mean increase in indirect bilirubin following smoking cessation reached 0.06mg/dl, whereas those who were not abstinent had a significantly lower average increase (0.02mg/dl). The increase with quitting is consistent with the differences in bilirubin levels observed between past and current smokers in cross-sectional epidemiological studies. For example, in a Belgian population (Van Hoydonck et al., 2001), the mean total bilirubin level was 0.06mg/dl higher for former smokers (mean = 0.47, SD = 0.25) compared to current smokers (mean = 0.41, SD = 0.19). Our findings demonstrate that this benefit occurs with short-term abstinence. Indeed, the mean differences observed in our study may be an underestimation since participants who were not continuously abstinent reduced their smoking. The half-lives of tobacco-associated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites, which may have mediated the hypothesized enzyme induction, are less than 10hr (St. Helen et al., 2012). Thus, a bilirubin increase as early as 1 week seems plausible.

One implication of the findings is that smoking cessation increases in bilirubin may be one mechanism for some of the short-term benefits of quitting smoking, such as improved endothelial function (Morita et al., 2006) and reduced cardiovascular risk (Rigotti, 1996). Future studies, potentially using animal models, are needed to determine if the association between bilirubin and health effects of smoking cessation is causal. Even if not causal, bilirubin change could be considered as part of a panel of biomarkers to motivate smoking cessation. Many of the health consequences of smoking are distant and uncertain (e.g., the person may or may not get lung cancer or coronary disease in the future). Having a biomarker that correlates with future consequences could help increase motivation to change by making the potential health benefits of quitting more immediately apparent. Studies in alcohol-dependent patients have documented that feedback about gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase as a marker of alcohol-related liver damage can lead to reductions in drinking (Kristenson, 1987; Nilssen, 1991). In smokers, studies have shown that reviewing arterial scanning images with patients to discuss smoking-related cardiovascular disease risk improved cessation (Hollands, Hankins, & Marteau, 2010) while another showed benefits on cessation from providing feedback about “lung age” based on spirometry results (Parkes, 2008). Since bilirubin measurements are included in standard chemistry panels, this biomarker could be translated easily to the clinic. Future research might also explore using bilirubin change to evaluate the consequences of other tobacco products.

Our study cannot disentangle the role of nicotine from other constituents in tobacco smoke on bilirubin concentrations. We suspect that non-nicotine constituents of tobacco smoke may be an important variable because increases in bilirubin occurred even though participants were using nicotine patches. Whether or not greater increases would occur in the absence of nicotine replacement or with other smoking cessation medications remains to be determined. Concurrent treatment with naltrexone, which undergoes conjugation in the liver, did not modify the findings; quitters showed larger mean increases in bilirubin than nonquitters irrespective of naltrexone dose.

As a secondary analysis of a clinical trial, there are limitations on the precision with which we were able to test our hypotheses. For example, fasting status, which affects bilirubin levels (White, Nelson, Pedersen, & Ash, 1981), was uncontrolled. In addition, our sample was composed primarily of Caucasians who reported smoking ≥20 cigarettes; thus, the findings may not generalize to lighter or minority smokers.

In conclusion, our study is the first to document that smoking cessation leads to increases in bilirubin concentrations using a longitudinal design. This finding is consistent with cross-sectional studies suggesting a direct role for smoking cessation in increasing bilirubin concentrations. Moreover, we demonstrate that these changes occur shortly after quitting and posit that these modest increases in bilirubin, an endogenous antioxidant, may contribute to some of the early benefits of quitting smoking.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addictions Services and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards K05 AA014715, P50 DA036151, P50 DA06151, and P30 CA16359. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, or Department of Mental Health and Addictions Services. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

SSO received honoraria as member of a workgroup on alcoholism clinical trial methodology sponsored by the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology/American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology funded by Alkermes, Abbott Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Ethypharm, Janssen, Schering Plough, Lundbeck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. SSO has been a consultant/advisory board member, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Inc., and Alkermes; received contracts as part of multisite studies for NABI Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly; received medication supplies, Pfizer; was a past partner, Applied Behavior Research; Scientific Panel Member, Hazelden Foundation; and inventor on an abandoned patent for naltrexone for smoking cessation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SSO and RW had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We thank D. Fiellin, MD, for reviewing the manuscript and R. Gueorguieva, PhD, for statistical advice.

REFERENCES

- Benowitz N. L. (2007). Cigarette smoking and the personalization of irinotecan therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 2646–2647. 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyath P., Gorrepati V. S., Peters I., Nookala V., Murphy M. E., Srouji N., Fischman D. (2010). High total bilirubin as a protective factor for diabetes mellitus: An analysis of NHANES data from 1999–2006. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 2, 201–206. 10.4021/jocmr425w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman D., Valluri A., Gorrepati V. S., Murphy M. E., Peters I., Cheriyath P. (2010). Bilirubin as a protective factor for rheumatoid arthritis: An NHANES study of 2003–2006 data. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 2, 256–260. 10.4021/jocmr444w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollands G. J., Hankins M., Marteau T. M. (2010). Visual feedback of individuals’ medical imaging results for changing health behaviour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD007434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins P. N., Wu L. L., Hunt S. C., James B. C., Vincent G. M., Williams R. R. (1996). Higher serum bilirubin is associated with decreased risk for early familial coronary artery disease. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vascular Biology, 16, 250–255. 10.1161/01.ATV.16.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall L. J., Rait G., Walters K., Swallow D. M., Pereira S. P., Nazareth I., Petersen I. (2011). Serum bilirubin and risk of respiratory disease and death. Journal of the American Medical Association, 305, 691–697. 10.1001/jama.2011.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., Kimm H., Yun J. E., Lee K. J., Jee S. H. (2012). Cigarette smoking and serum bilirubin subtypes in healthy Korean men: The Korea Medical Institute study. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 45, 105–112. 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.2.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristenson H. (1987). Methods of intervention to modify drinking patterns in heavy drinkers. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, 5, 403–423. 10.1007/978-1-4899-1684-6_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan M., Wattigney W. A., Srinivasan S. R., Berenson G. S. (1997). Serum bilirubin distribution and its relation to cardiovascular risk in children and young adults. Atherosclerosis, 131, 107–113. 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)06088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz M., Seiberling M., Thomann P. (1998). Laboratory values and vital signs in male smokers and nonsmokers in phase I trials: A retrospective comparison. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 38, 1144–1150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K., Tsukamato T., Naya M., Noryasu K., Inubushi M., Shiga T., … Tamaki N. (2006). Smoking cessation normalizes coronary endothelial vasomotor response assessed by 15O-water and PET in healthy young smokers. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 47, 1914–1920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilssen O. (1991). The Tromsö Study: Identification of and a controlled intervention on a population of early stage risk drinkers. Preventative Medicine, 20, 518–528. 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90049-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny L., Vitek L. (2003). Inverse relationship between serum bilirubin and atherosclerosis in men: A meta-analysis of published studies. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 228, 568–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley S. S., Cooney J. L., Krishnan-Sarin S., Dubin J. A., McKee S. A., Cooney N. L., … Jatlow P. (2006). A controlled trial of naltrexone augmentation of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 667–674. 10.1001/archinte.166.6.667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes G. (2008). Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: The Step2quit randomized controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 336, 598–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti N. A. (1996). Cigarette smoking and coronary heart disease: Risks and management. Cardiology Clinics, 14, 51–68. 10.1016/S0733-8651(05)70260-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo A. M., Berselli P., Zava S., Montorfano G., Negroni M., Corsetto P., Berra B. (2010). Endogenous antioxidants and radical scavengers. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 698, 52–67. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7347-4_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwertner H. A. (1998). Association of smoking and low serum bilirubin antioxidant concentrations. Atherosclerosis, 136, 383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Helen G., Goniewicz M. L., Dempsey D., Wilson M., Jacob P., III, Benowitz N. L. (2012). Exposure and kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in cigarette smokers. Chemical Research and Toxicology, 25:952–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R., Yamamoto Y., McDonagh A. F., Glazer A. N., Ames B. N. (1987). Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science, 235, 1043–1046. 10.1126/science.3029864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temme E. H., Zhang J., Schouten E. G., Kesteloot H. (2001). Serum bilirubin and 10-year mortality risk in a Belgian population. Cancer Causes & Control, 12, 887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health [Google Scholar]

- van der Bol J. M., Mathijssen R. H., Loos W. J., Friberg L. E., van Schaik R. H., de Jonge M. J., … de Jong F. A. (2007). Cigarette smoking and irinotecan treatment: Pharmacokinetic interaction and effects on neutropenia. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 2719–2726. 10.1200/jco.2006.09.6115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoydonck P. G., Temme E. H., Schouten E. G. (2001). Serum bilirubin concentration in a Belgian population: The association with smoking status and type of cigarettes. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 1465–1472. 10.1093/ije/30.6.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watchko J. F., Tiribelli C. (2013). Bilirubin-induced neurologic damage--mechanisms and management approaches. The New England Journal of Medicine, 369, 2021–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G. L., Jr., Nelson J. A., Pedersen D. M., Ash K. O. (1981). Fasting and gender (and altitude?) influence reference intervals for serum bilirubin in healthy adults. Clinical Chemistry, 27, 1140–1142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zevin S., Benowitz N. L. (1999). Drug interactions with tobacco smoking. An update. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 36, 425–438. 10.2165/00003088-199936060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Wen C. P., Liang D., Skinner H., Gu J., Chow W.-H., … Wu X. (2013). Metabolomic profiling identifies bilirubin as a novel serum marker of lung cancer. Cancer Research, 73(Suppl. 1), 10 [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S. D., Horn P. S., Sherman K. E. (2004). Serum bilirubin levels in the U.S. population: Gender effect and inverse correlation with colorectal cancer. Hepatology, 40, 827–835. 10.1002/hep.20407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]