This document is a consensus proposal aimed at refining the classification and terminology of mast cell leukemia (MCL) and related disorders. Novel aspects in the classification include the delineation into chronic MCL and acute MCL, and the definition of patients with aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM) who are transforming or have a high risk of transformation, into MCL, termed ASM-t.

Keywords: leukemia, mastocytosis, mast cells, KIT D816V, tryptase, prognostication

Abstract

Mast cell leukemia (MCL), the leukemic manifestation of systemic mastocytosis (SM), is characterized by leukemic expansion of immature mast cells (MCs) in the bone marrow (BM) and other internal organs; and a poor prognosis. In a subset of patients, circulating MCs are detectable. A major differential diagnosis to MCL is myelomastocytic leukemia (MML). Although criteria for both MCL and MML have been published, several questions remain concerning terminologies and subvariants. To discuss open issues, the EU/US-consensus group and the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) launched a series of meetings and workshops in 2011–2013. Resulting discussions and outcomes are provided in this article. The group recommends that MML be recognized as a distinct condition defined by mastocytic differentiation in advanced myeloid neoplasms without evidence of SM. The group also proposes that MCL be divided into acute MCL and chronic MCL, based on the presence or absence of C-Findings. In addition, a primary (de novo) form of MCL should be separated from secondary MCL that typically develops in the presence of a known antecedent MC neoplasm, usually aggressive SM (ASM) or MC sarcoma. For MCL, an imminent prephase is also proposed. This prephase represents ASM with rapid progression and 5%–19% MCs in BM smears, which is generally accepted to be of prognostic significance. We recommend that this condition be termed ASM in transformation to MCL (ASM-t). The refined classification of MCL fits within and extends the current WHO classification; and should improve prognostication and patient selection in practice as well as in clinical trials.

introduction

The proposal of the World Health Organization (WHO) divides systemic mastocytosis (SM) into indolent SM (ISM), SM with an associated hematopoietic non-mast cell (MC) lineage disease (SM-AHNMD), aggressive SM (ASM) and MC leukemia (MCL) [1–4]. A number of studies have confirmed the prognostic significance of this classification [5–8]. Patients with MCL are characterized by leukemic expansion of MCs in the bone marrow (BM) and other organ systems [1–4, 9–12]. In a subgroup of patients, circulating MCs are detected. In the classical ‘leukemic’ variant of MCL, MCs comprise at least 10% of all nucleated blood cells [9–12]. In the ‘aleukemic’ variant of MCL, circulating MCs account for <10% [1–4, 13]. In both groups of patients, MCs represent at least 20% of all nucleated cells on BM smears, which remains the primary diagnostic criterion of MCL [1–5].

MCs in MCL are usually immature, sometimes with bi- or multi-lobed nuclei, also termed promastocytes [5]. Metachromatic blasts are also found in these patients. In a very few patients with MCL, more mature forms represent the predominant type of MCs on BM smears. The phenotype of MCs in MCL is similar to that found in patients with ASM [1–4, 10, 14–16]. Notably, MCs in MCL usually express CD9, CD25, CD33, CD44 and CD117 (KIT) [1–4, 14–16]. The CD2 antigen (LFA-2) may also be detected on MCs in MCL [10]. However, the percentage of ‘CD2-positive’ cases is low, and if detected, the levels of CD2 on MCs are usually lower in MCL compared with ISM, suggesting that CD2 expression decreases during malignant progression [14–18]. Tryptase and FcεRI expression may also be decreased in MCs in MCL.

Other markers, like CD52, HLA-DR or CD123, may be expressed at higher levels on MCs in MCL compared with ISM [15, 16]. The Ki-1 antigen (CD30) is usually also expressed more abundantly in MCs in MCL [19, 20]. However, in contrast to CD52, the difference in CD30 expression is only seen in the cytoplasm, but not on the surface of neoplastic MCs [19–21].

With regard to genetic abnormalities, the molecular biology of MCL is similar to that of other SM variants. In many cases, the KIT mutation D816V is detectable in neoplastic cells. However, in contrast to ISM, the frequency of this mutation is lower in MCL (typical ISM: >90% of patients versus MCL: 50%–80% of cases). MCs in patients with MCL may also exhibit other mutations at codon 816 of KIT or mutations in other critical regions of KIT [22–27]. In a subset of patients with MCL, no KIT mutations are found [12, 24].

Despite the rarity of the condition, MCL is known to manifest in different forms and variants. Apart from the above-mentioned ‘leukemic’ and ‘aleukemic’ variants of MCL, the following aspects reflect disease heterogeneity. First, MCL may or may not present with an AHNMD, often in the form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [28–30]. These cases (MCL–AML) exhibit a substantial increase (>20%) in myeloblasts and have to be distinguished from patients with myelomastocytic leukemia (MML) where an AML may also be diagnosed, but criteria to diagnose SM are not met. In patients with MCL, a prephase of ASM or MC sarcoma may or may not be recognized [31, 32]. Finally, whereas the course of MCL is usually aggressive, a few patients with MCL present with a more indolent, stable clinical course, sometimes even without C-Findings in the initial phase.

As has been stated, an important differential diagnosis to MCL is MML [33–35]. In these MML patients, an underlying advanced myeloid neoplasm (usually with a blast cell excess) is found and is accompanied by a leukemic spread of immature atypical MCs. The criteria to diagnose SM and thus MCL are not fulfilled [33–35]. By definition, MCs in MML account for at least 10% of all nucleated cells in BM or peripheral blood smears [33–35]. In other patients with advanced myeloid neoplasms, MCs also represent a significant population of neoplastic cells, but criteria to diagnose MML are not met (<10% MCs).

All in all, several open questions remain concerning the diagnosis and classification of MCL and MML. To address these questions, the EU/US consensus group and the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) were involved in a series of collaborative meetings and workshops in the years 2011, 2012 and 2013. Outcomes from these discussions and resulting consensus statements are provided in this article.

basic definitions and diagnostic criteria to separate MCL from MML

Based on generally accepted criteria, MCL is defined by (i) SM criteria, namely at least one major and one minor or at least three minor SM criteria and (ii) the presence of at least 20% MCs on BM smears [1–4]. Most patients with MCL present with the major SM criterion, namely multifocal sheets and clusters of MCs in BM sections; and in a subgroup of patients, circulating MCs are detectable. If <10% of circulating leukocytes are MCs or no MCs are detected in the blood, the diagnosis is ‘aleukemic MCL’ [1–4]. Clinical signs and symptoms of organ damage caused by MC infiltration (C-Findings) are usually present. In addition, mediator-related symptoms are often recorded. In most MCL patients, the serum tryptase levels are markedly elevated (>200 ng/ml, often >500 ng/ml) and may increase rapidly (Table 1). MCL may involve several different organ systems. Organ damage is usually found at diagnosis or develops within a short time. Splenomegaly may be present or develops over time. The skin is the only organ spared in MCL. Thus, in the vast majority of MCL cases, no typical maculopapular skin lesions are identified. However, these patients may still experience MC mediator-related skin symptoms such as flushing.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and laboratory features typically identified in patients with MCL or MML

| Feature | Mast cell leukemia (MCL) | Myelomastocytic leukemia (MML) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||

| Skin lesions | Usually absent | Absent |

| Splenomegaly | Found in a subset (terminal stage) | Usually present at diagnosis |

| Liver involvement with ascites | Often found | Usually not found |

| Mediator symptoms | Frequent | Frequent |

| Laboratory (blood) | ||

| Serum tryptase (ng/ml) | >200 (often >500) | <100 (often <50) |

| Circulating MCs | In a subset of patients | In a subset of patients |

| Circulating blasts | No (except MCL–AML) | In a subset of patients |

| Bone marrow (BM) findings | ||

| Underlying non-MC myeloid neoplasms | No (except MCL-AHNMD) | Yes |

| Increase in myeloblasts | Usually not found (except MCL–AHNMD) | Almost always seen |

| Clusters and sheets of MCs in BM histology | Yes | No |

| Diffuse BM MC infiltrate | Yes | Yes |

| MCs in BM smears | ≥20% | ≥10% |

| Karyotype | Normal or abnormal with a few lesionsa | Usually complexa |

| MC express CD25 | Yes | No |

| KIT D816V or other codon 816 mutation | Present | Not found |

| KIT mutations in non-816-codons | Found in a subset | Found in a subset |

aIn MML, the karyotype usually reflects the nature of the underlying disease, whereas no recurrent chromosome abnormalities are known for patients with MCL.

AHNMD, associated clonal hematopoietic non-MC-lineage disease; MCs, mast cells.

Myelomastocytic leukemia (MML) is a term applied to advanced myeloid (non-MC) neoplasms in which MC differentiation is prominent, but SM criteria are not fulfilled, thereby distinguishing MML from MCL [33, 35]. These patients may suffer from an advanced myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), usually refractory anemia with an excess of blasts, AML, an accelerated phase of a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) with or without eosinophilia or an MDS/MPN overlap syndrome [33–37]. In MML, MCs comprise at least 10% of all nucleated cells in peripheral blood or/and BM smears. Leukemic MCs in MML are usually immature or are recognized as metachromatic blasts with very low expression of cytoplasmic enzymes (tryptase) and absent or low surface FcεRI. Peripheral blood and BM cells exhibit major signs of dysplasia [33–37]. The major diagnostic criterion of SM (aggregates of >15 MCs in tissue sections) is absent in MML, although a diffuse interstitial increase in MCs is noted. In a vast majority of cases, a complex karyotype is found [33–37]. A KIT mutation may also be detected in these patients (PV, unpublished observation), but codon 816-mutations are typically not detectable in MML [34, 35]. However, MCs in MML may exhibit other clonal lesions typically found in the underlying myeloid neoplasm [33–37]. As in MCL, skin lesions are usually absent. Splenomegaly is found at diagnosis in most MML patients [33–37]. In addition, patients with MML often suffer from mediator-related symptoms or a coagulation disorder associated with major episodes of blood loss [37]. The serum tryptase level is also elevated in MML, but is usually below 100 ng/ml (often <50 ng/ml). Table 1 shows typical features of MML and MCL.

To date, the WHO has not recognized MML as a separate entity in their classification proposal. We consider this an important open issue, since these cases and similar conditions are often called ‘unclassifiable’ or ‘not met by WHO criteria’. Therefore, we propose that the WHO should consider the inclusion of MML (as subtype of transformed MDS/AML) in their next update. An important justification is that some of these cases may easily be confused with (acute) basophilic leukemia. Therefore, the diagnosis of MML should be based on a thorough histopathological and immunophenotypic analysis of affected cells [33–37]. An overview of differential diagnoses to MCL and MML is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of differential diagnoses to consider in patients with suspected mast cell leukemia

| Differential diagnosis | Typical findings/features |

|---|---|

| Myelomastocytic leukemia (MML) | No SM criteria, MCs ≥10% in BM or PB smears, BM dysplasia, MDS or AML, or chronic myeloid leukemia in blast phase, no KIT mutation in codon 816 found |

| Chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL) | SM criteria not fulfilled, CD25+ atypical neoplastic MCs found in the BM; but no KIT mutation in codon 816 found, diagnosis=CEL, often with molecular lesions such as fusion genes involving PDGFRsa |

| Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | BCR/ABL1+, immature metachromatic cells in CML (accelerated phaseb or blast phase) are basophils by immunophenotypingc and only a few MCs are found; no mutation in codon 816 of KIT is found |

| Acute basophilic leukemia | Massive increase in immature basophils, confirmed by immunophenotypingc, no increase in mast cells, no KIT mutation in codon 816 is found |

| Chronic basophilic leukemia | Massive increase in basophils, confirmed by immunophenotypingc; no increase in mast cells found, no KIT mutation in codon 816 is found |

aTesting for the FIP1L1/PDGFRA fusion gene is carried out using PCR and FISH.

bIn a few patients with CML, a so-called basophil-crisis may develop.

cImmunophenotyping should be carried out by both flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Valuable markers for basophil-detection and enumeration include CD123 and CD203c (flow cytometry) as well as BB1 and 2D7 (immunohistochemistry).

MCs, mast cells; SM, systemic mastocytosis; BM, bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

staging and grading investigations recommended in patients with MCL and MML

A thorough investigation of the BM remains the key to a correct diagnosis in patients with suspected MCL or MML. Both biopsy material and the aspirate are required to establish a correct diagnosis [1–5, 38]. The biopsy material must undergo a detailed histomorphological, cytochemical and immunohistochemical investigation (see section below). The aspirate smear must be examined for the presence, numbers (percentage) and morphology of MCs, and this analysis is to be carried out at a fair distance from any BM particles or larger cell aggregates [5, 38]. In all patients, the BM aspirate undergoes a detailed cytogenetic analysis, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), flow cytometry and molecular studies [1–4, 38]. The FISH panel should cover major lesions detectable in MDS and secondary AML. Flow cytometry analysis should be carried out according to guidelines provided by the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) [39]. Molecular studies should include an ‘MDS and AML panel’ (major lesions otherwise found in MDS or AML without SM) as well as a mutation analysis of KIT [22, 38]. In a first step, a screen for KIT codon 816 mutations is sufficient [38]. If this analysis is negative, sequencing of the entire KIT gene should be considered. This is of importance in patients with advanced SM and MCL/MML, since several mutations outside of codon 816 may generate kinases that are responsive to treatment with imatinib and/or other KIT-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

For the future, additional assays should be considered in order to define mutation profiles, amplifications or deletions in critical genes and oncogenic pathways that can be detected and may be prognostic in MCL and other forms of advanced SM [40–42].

BM histology and immunophenotyping

A thorough histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of the BM remains an important step toward the diagnosis of SM, including MCL [1–4, 43–45]. The histologic hallmark of MCL is the excessive dense and usually mixed (diffuse and focal) infiltration of the BM by immature neoplastic MCs [1–4, 43–45]. In some patients, the diffuse component of the MC infiltrate is predominant. However, the major SM criterion will be invariably fulfilled [43–47]. In contrast, in MML, MCs are loosely scattered and form an interstitial (diffuse) BM infiltration pattern, but typically they do not cluster in larger aggregates or sheets. In other words, the major SM criterion is not fulfilled in MML.

A number of markers have been proposed as standard and are to be applied in the immunohistochemical evaluation of the BM in (suspected) MCL and MML. The basic (standard) panel consists of CD34, KIT (CD117), tryptase, CD25, CD30, a megakaryocyte marker such as CD31, CD42 or CD61, a B-cell marker and a T-cell marker [1–4, 38, 43–45, 48]. Other antigens, such as CD2 or chymase, are sometimes also applied. However, these antigens are of little if any value in routine practice. Neoplastic MCs in MCL usually express KIT, low tryptase and low FcεRI, and often also CD25 and CD30, but do not express CD34 (Table 3). In MML, MCs also express KIT and tryptase, but usually stain negative for CD25 [35–37]. Chymase and CD2 are usually not displayed by MCs in MCL and MML. These two antigens may be detected in MCs in patients with ISM and SSM [49, 50]. However, both markers are weakly expressed and therefore are not recommended for grading in daily practice. With regard to CD30, the difficulty is that MCs in ISM may also express some (low) amounts of the antigen, and that in a few patients with MCL, MCs stain negative for CD30 [19, 21]. Some markers, including CD52, HLA-DR and CD123, may also be expressed more abundantly in MCs in ASM and MCL. However, again, no absolute correlations are found, and results obtained should be interpreted with caution. Ki-67 is a well-established proliferation marker that is usually not expressed in neoplastic MCs in SM as MCs are usually non-proliferating cells. However, in MCL patients with rapidly progressing disease, the number of Ki-67-positive MCs is markedly increased [51].

Table 3.

Phenotypic heterogeneity of mast cells (MCs) in MC disorders

| Marker | Markers expressed in MCs in |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal BM | ISM | SSM | ASM | MCL | MML | |

| CD34/HPCA-1 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CD117/KIT | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tryptase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD33/Siglec-3 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD123/IL-3RA | − | − | − | +/− | +/− | − |

| CD2/LFA-2 | − | +/− | +/− | −/+ | −/+ | −a |

| CD25/IL-2RA | − | + | + | + | + | −a |

| CD30/Ki-1 | − | −/+ | + | + | + | n.k. |

| FcϵRI | + | + | + | + | −/+ | − |

aIn a few cases, one of the two markers, either CD2 or CD25 may be expressed in neoplastic MCs in MML. +, expressed in MCs in almost all (>90% of) SM patients, +/−, expressed in a majority of MCs in a considerable subset of SM patients; −/+, expressed in a minority of MCs in a smaller subset of SM patients; −, not expressed in neoplastic MCs in SM patients.

BM, bone marrow; HPCA-1, human precursor cell antigen-1; IL-3, interleukin-3; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; SSM, smouldering SM; ASM, aggressive SM; MCL, mast cell leukemia; MML, myelomastocytic leukemia; n.k., not known.

the BM smear: recommended standards and caveats

Major pre-analytical pitfalls include a ‘dry tap’ (punctio sicca), a major ‘contamination’ of the aspirate sample with peripheral blood cells and a suboptimal quality of the smear. With regard to aspiration, it is sometimes difficult to perform a marrow-rich aspirate in advanced SM because of BM fibrosis or densely packed cells (high infiltration grade). Therefore, the consensus group recommends that for all patients with (suspected) advanced SM, a touch-preparation is to be carried out from the BM biopsy material. Even if a smear is prepared, the ‘touch-prep-slides’ should also be sent to all involved diagnostic laboratories. In the case of a major blood contamination, which is usually seen immediately on the smears (none to few BM particles on the slides), a second aspiration from a different location and with a new needle is recommended. The smears should always be checked to guarantee optimal quality after aspiration and should then be air-dried before being processed and stained. It is mandatory that the staff of each involved laboratory, including the flow cytometry-team and the pathologist, receives unstained good-quality BM aspirate smears (at least two slides) together with the BM sample(s) that should be processed and analyzed. In some cases, a second BM biopsy or/and aspirate may be required.

morphologically identifiable stages of MC differentiation/maturation

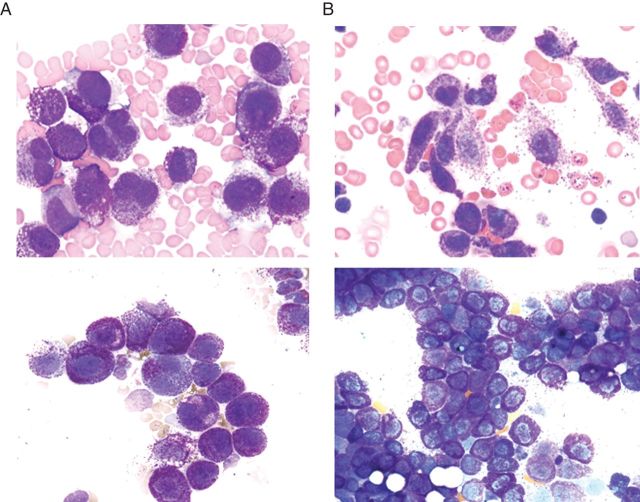

A morphologic classification of neoplastic MCs has been published and is a generally accepted standard of evaluation of BM smears in SM [5]. The classification is based on distinct stages of maturation of normal MCs and corresponding morphological stages of MC maturation detectable in BM smears in SM [5]. Based on these morphologies, the following subtypes of MCs have been defined: (i) typical mature tissue MCs with a round central nucleus, (ii) atypical MCs type I, (iii) atypical MCs type II and (iv) metachromatically granulated blast cells (metachromatic blasts) (Figure 1). Morphologic criteria defining the various types of MCs are depicted in Table 4. It is important that these criteria are applied in all patients using a ‘good-quality BM smear’ in order to grade MC populations correctly [5, 38]. In addition, it is important to define the numbers of MCs in BM smears accurately. A total of at least 200–400 nucleated cells should be counted as the basis of enumeration and grading of MCs in BM smears, and such enumeration should be carried out in areas in which no packed cells or BM particles are observed [38]. An increase in immature atypical MCs or metachromatic blasts over 10% of all MCs on a BM smear must be regarded as ‘high grade morphology’. Flow cytometry is usually helpful to confirm the numbers and percentage of MCs in the BM and to determine the degree of maturation of MCs and MC-committed precursor cells [52].

Figure 1.

Morphologically defined subsets of mast cells in bone marrow smears. Wright–Giemsa staining may reveal metachromatically granulated blast cells (A), atypical mast cells type II, also referred to as promastocytes (B), atypical, spindle-shaped mast cells type I (C) or mature (normal) tissue mast cells. Note the bi-lobed nuclei in promastocytes.

Table 4.

Cytomorphologic criteria of mast cell (MC) types detected in the BM smear in patients with MCL, other variants of systemic mastocytosis (SM) or myelomastocytic leukemia (MML)

| Type of MC | Criteria | Typically found in patients with |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MML | Acute MCL | Chronic MCL | ASM | ISM | ||

| Typical MC | Round cells, well granulated, central round nucleus | − | − | −/+a | − | −/+a |

| Atypical MC type I | (a) Elongated surface projections, often spindle-shaped cells, (b) hypogranulated cytoplasm, (c) oval decentralized nucleus. → 2 or 3 of a/b/c | − | − | +/− | +/− | + |

| Atypical MC type II = promastocyte | Mostly immature, with bi- or multi-lobed nuclei | + | + | +/− | +/− | −/+ |

| Metachromatic blast | Myeloblast with few or several metachromatic granules | + | + | −/+ | −/+ | − |

aIn patients with well-differentiated SM (WDSM), mast cells are mostly round and well-granulated cells. In some of these patients, the disease may progress to chronic MCL with round MCs.

MC(s), mast cell(s); ASM, aggressive SM; ISM, indolent SM.

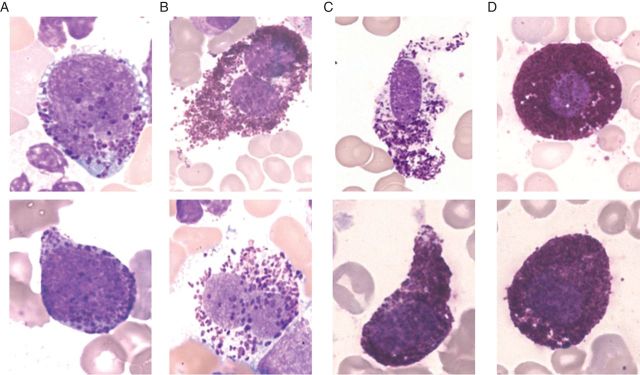

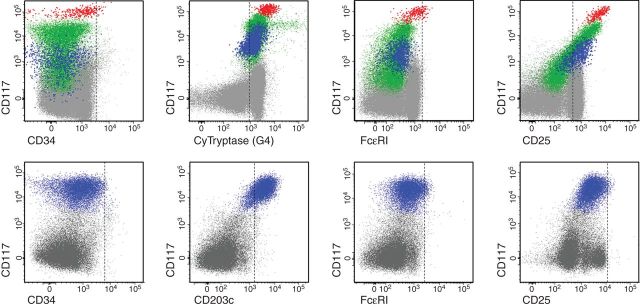

clinical significance of cytological staging and grading

In most patients with MCL, MCs are rather immature. These cells often represent metachromatic blasts or atypical MCs type II (promastocytes) (Table 4). However, there are a few patients with MCL, in whom most MCs represent more mature cells (Figure 2). A number of previous studies have shown that the percentage of MCs in BM smears recorded in SM is of prognostic significance [5]. In MCL, MCs comprise at least 20% of all nucleated cells on BM smears. However, even an increase to ≥5% may be prognostically unfavorable compared with patients with <5% MCs in BM smears. These patients (5%–19% MC) are usually suffering from ASM with rapid progression, and several of these patients may progress to overt MCL within a relatively short time (usually within several months). Therefore, the consensus group judged it appropriate to propose defining these patients (5%–19% MCs in BM smears) as a separate category of ASM, namely ASM in transformation (ASM-t). Another important aspect is the morphology of MCs and their immunophenotype. As mentioned, MCs in patients with MCL may be more mature or more immature cells. Since the morphology of MCs in SM has been considered to be of prognostic significance in SM patients [5], the consensus group was not surprised to learn that a more mature morphology of MCs in MCL (>90% mature MCs) is a more favorable prognostic sign. Indeed, a few patients with MCL present with mostly mature MCs, and particularly these patients may have a less aggressive clinical course, sometimes even without C-Findings, compared with the majority of MCL patients with a high-grade MC morphology. Figure 2 shows examples for high- and low-grade morphologies in MCL. These cells may either be round cells or predominantly spindle-shaped MCs. An interesting observation is that some of the patients with the so-called well-differentiated type of SM (WDSM) may progress to MCL with a mature MC morphology (round MCs) and a less aggressive clinical course (Figure 2). It is also noteworthy that rapidly progressing MCL usually shows a high proliferation rate (>50% Ki-67-positive MCs), whereas slowly progressing (chronic) MCL shows a low proliferation rate of MCs (<10% of MCs are Ki-67-positive). Finally, it is important to note that the phenotype of neoplastic MCs in MCL and the stage of maturation can be determined by flow cytometry (Figure 3). In patients with acute MCL, at least subsets of MCs appear to be very immature. However, even in these cases as well as in MML, neoplastic MCs lack CD34 [33–35].

Figure 2.

Typical morphological features of mast cells observed in patients with acute or chronic mast cell leukemia (MCL). Wright–Giemsa-stained bone marrow smears obtained from two patients with acute MCL (A) and two patients with chronic MCL (B). Note the immature morphology of several of the mast cells (MCs) in the patients with acute MCL (A). Some of these MCs exhibit bi-lobed nuclei. In contrast, in patients with chronic MCL, most MCs exhibit a mature morphology, either with spindle-shaped forms (upper panel in B) or with round and well-granulated MCs (lower panel in B), whereas immature forms are very rare or even not detectable in these patients.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of mast cell differentiation profiles in the bone marrow of patients with MCL. Bone marrow aspirate samples were obtained from a patient with acute MCL (upper panels; the same case shown in the lower left panel of Figure 2) and chronic MCL (lower panels; case shown in the lower right panel of Figure 2). Expression of cell surface antigens on KIT+ (CD117+) mast cells (events colored blue, green and red) was determined by monoclonal antibodies and multicolor flow cytometry. Mast cells in MCL typically express KIT and lack CD34 (left panels). Mast cells usually also express tryptase and CD203c. However, mast cells in MCL express only low levels of (or no detectable) high-affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI) and only low levels of CD2, whereas CD25 is often expressed on mast cells in MCL.

proposed categories of MCL

Based on WHO criteria [1–5], MCL is divided into a leukemic variant (circulating MCs ≥10%) and an aleukemic variant of MCL (circulating MCs <10%). In both categories, the outcome is poor. During the past few years, additional information concerning the biology of MCL has been discussed at expert meetings. One important concept is that MCL may develop as either a de novo disease or as a secondary leukemia following ASM or MC sarcoma. Based on these observations, we believe it justified to separate a primary (de novo) variant of MCL from secondary MCL (Table 5). Finally, as mentioned above, in a few cases of MCL, the course of the disease may be less aggressive and more chronic even if circulating MCs are detectable. These cases may later progress and the overall outcome may be limited. However, the overall prognosis may still be better than in the acute variant of MCL, especially when no C-Findings are detectable.

Table 5.

Delineation between various forms of mast cell leukemia (MCL)

| MCL variants | Defining features/criteria |

|---|---|

| Leukemic MCL | At least 10% circulating MCs |

| Aleukemic MCL | Less than 10% of blood leukocytes are MCs |

| Acute MCLa | C-Finding(s)a present, mostly immature MCs |

| Chronic MCL | C-Findings usually absent, less aggressive course, mature MCs usually predominate |

| Primary MCL | No antecedent SM or other myeloid neoplasm |

| Secondary MCL | Transformation of SM (usually ASM) or MC sarcoma |

aOne C-Finding is sufficient to call the condition acute MCL.

MCs, mast cells.

We therefore propose to differentiate between chronic MCL without C-Findings and acute MCL with C-Findings (Table 5). In the final diagnosis, one, two or all three defining features should be considered, depending on available information and the clinical situation and laboratory findings. Likewise, a patient could suffer from secondary acute aleukemic MCL or from primary chronic MCL.

proposed variants of MML

As mentioned above, MML has to be separated from any type of SM, including MCL. Rather, in patients with MML, another underlying (advanced) myeloid neoplasm is identified and serves as a major diagnostic criterion of MML. Therefore, MML can be naturally divided into subcategories based on the type of the underlying myeloid neoplasm. In addition, patients with MML could also be split into leukemic and aleukemic variants, similar to MCL, although the clinical implication of these subtypes remains unknown. Otherwise, MML should always be regarded as a secondary condition. Also, as mentioned above, MML should not be regarded as a subvariant of MCL or SM.

imminent prephases of MCL and MML: definition and proposed terminology

The group also discussed potential imminent prephases of MCL and MML. In the case of MCL, it is important to note that the prognosis clearly correlates with the numbers of atypical immature MCs recorded in BM smears, even when MCs comprise <20%. Although this correlation was described in 2001 [5], the related conditions have not been addressed by any nomenclature to date. The prognosis may be particularly poor if the percentage of MCs in the BM smear increases to 5% or more of all nucleated BM cells. In many of these cases, ASM may progress to overt MCL within a relatively short time (months). To address this important point, the group considered to define this special situation and to introduce the term ‘ASM in transformation’ (ASM-t) for these patients. In other words, the condition ASM-t is defined by SM criteria, C-Findings and a MC percentage of 5%–19% of all nucleated cells in BM smears.

In MML, the situation is similar, but the prognostic implications of an increased MC percentage in the range of 5%–9% have not been established in the same way as for ASM-t, although the condition has been described [53, 54]. After a thorough discussion through several meetings, the group concluded that it is too early to define this condition using a special term, such as myelomastocytosis (MM) or ‘myelomastocytic’ transformation. For the moment, the condition should thus be described as a secondary clonal increase in immature atypical MCs (metachromatic cells) neither meeting the criteria of SM/MCL nor criteria of MML. Finally, several differential diagnoses have to be considered in patients with apparently unclassifiable myeloid neoplasm and an increase in immature metachromatic cells [46, 53, 55] (Table 2).

follow-up and associated parameters

In an early phase of diagnosis, it is essential to monitor several disease-specific parameters, especially if the diagnosis is in question or a (potential) prephase of MCL (ASM-t) or MML has been diagnosed. In these patients, it is important to record the serum tryptase level and the blood counts (in close time intervals) in order to recognize transformation into MCL and to delineate between more chronic and acute disease variants. The standard assay for measurement of tryptase has a maximum value of 200 ng/ml. However, patients with MCL usually show levels well above this maximum value. Therefore, careful dilution of serum samples may be necessary for accurate measurement of tryptase levels. A rapid increase in MCs in the BM or blood; and rapid increase in serum tryptase (e.g. by 100 ng/ml within a few weeks) are indicative of acute MCL. Progression or occurrence of one or more C-Finding(s) is also indicative of acute MCL. Treatment response criteria are available [11, 38, 56] and work for MCL, and similar criteria can also be applied for MML, although the value of these criteria in MML has not been formally proven yet. The serum tryptase level remains a key follow-up and treatment-response parameter in MCL. Other useful parameters in MCL may be alkaline phosphatase (if initially elevated), eosinophil counts and MC numbers in the blood and BM.

conclusions and future perspectives

Because of the rarity and complexity of the disease, immaturity of clonal cells, and absence of skin involvement, the diagnosis of MCL and MML is a challenge in clinical hematology. Although criteria for MCL and MML are available, several questions remain concerning subvariants, criteria, the diagnostic interface, prephases of disease and the differential diagnoses. To address these questions, the EU/US consensus group and the ECNM have initiated a discussion-forum in which updated recommendations, refined criteria and classification proposals have been developed. The resulting refinements and updated classification should facilitate diagnostic studies and help in reaching a correct final diagnosis in patients with these disorders. For the future, we hope that the WHO will consider these proposals and implement these refinements in the updated classification of hematopoietic malignancies.

Supported by: Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung in Österreich, grants #SFB-F46-10 and #SFB-F47-04, a research grant of The Mastocytosis Society (TMS) and in part by the NIAID Division of Intramural Research.

funding

No funding was received for this study.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgements

We like to thank Sabine Cerny-Reiterer, Barbara Peter, Ghaith Wedeh and Emir Hadzijusufovic for their helpful support and for helpful discussions.

references

- 1.Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25(7):603–625. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valent P, Horny H-P, Li CY, et al. Mastocytosis (mast cell disease) In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al., editors. World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. France: IARC Press Lyon; 2001. pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horny HP, Akin C, Metcalfe DD, et al. Mastocytosis (mast cell disease) In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, editors. World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Mast cell proliferative disorders: current view on variants recognized by the World Health Organization. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2003;17(5):1227–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(03)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperr WR, Escribano L, Jordan JH, et al. Morphologic properties of neoplastic mast cells: delineation of stages of maturation and implication for cytological grading of mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25(7):529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113(23):5727–5736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escribano L, Alvarez-Twose I, Sánchez-Muñoz L, et al. Prognosis in adult indolent systemic mastocytosis: a long-term study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis in a series of 145 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(3):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. Prognostically relevant breakdown of 123 patients with systemic mastocytosis associated with other myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114(18):3769–3772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Li CY, Hoagland HC, et al. Mast cell leukemia: report of a case and review of the literature. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1986;61(12):957–966. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalton R, Chan L, Batten E, et al. Mast cell leukaemia: evidence for bone marrow origin of the pathologic clone. Br J Haematol. 1986;64(2):397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis and related mast cell disorders: current treatment options and proposed response criteria. Leuk Res. 2003;27(7):635–641. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgin-Lavialle S, Lhermitte L, Dubreuil P, et al. Mast cell leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(8):1285–1295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baghestanian M, Bankl HC, Sillaber C, et al. A case of malignant mastocytosis with circulating mast cell precursors: biologic and phenotypic characterization of the malignant clone. Leukemia. 1996;10(1):159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escribano L, Díaz-Agustín B, Bellas C, et al. Utility of flow cytometric analysis of mast cells in the diagnosis and classification of adult mastocytosis. Leuk Res. 2001;25(7):563–570. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teodosio C, García-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, et al. Mast cells from different molecular and prognostic subtypes of systemic mastocytosis display distinct immunophenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(3):719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teodosio C, García-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, et al. Gene expression profile of highly purified bone marrow mast cells in systemic mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escribano L, Orfao A, Díaz-Agustin B, et al. Indolent systemic mast cell disease in adults: immunophenotypic characterization of bone marrow mast cells and its diagnostic implications. Blood. 1998;91(8):2731–2736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escribano L, Orfao A, Villarrubia J, et al. Sequential immunophenotypic analysis of mast cells in a case of systemic mast cell disease evolving to a mast cell leukemia. Cytometry. 1997;30(2):98–102. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970415)30:2<98::aid-cyto4>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sotlar K, Cerny-Reiterer S, Petat-Dutter K, et al. Aberrant expression of CD30 in neoplastic mast cells in high-grade mastocytosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(4):585–595. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valent P, Sotlar K, Horny HP. Aberrant expression of CD30 in aggressive systemic mastocytosis and mast cell leukemia: a differential diagnosis to consider in aggressive hematopoietic CD30-positive neoplasms. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(5):740–744. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.550072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgado JM, Perbellini O, Johnson RC, et al. CD30 expression by bone marrow mast cells from different diagnostic variants of systemic mastocytosis. Histopathology. 2013;63:780–787. doi: 10.1111/his.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arock M, Valent P. Pathogenesis, classification and treatment of mastocytosis: state of the art in 2010 and future perspectives. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3(4):497–516. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mital A, Piskorz A, Lewandowski K, et al. A case of mast cell leukaemia with exon 9 KIT mutation and good response to imatinib. Eur J Haematol. 2011;86(6):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joris M, Georgin-Lavialle S, Chandesris MO, et al. Mast cell leukaemia: c-KIT mutations are not always positive. Case Rep Hematol. 2012;2012:517546. doi: 10.1155/2012/517546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Georgin-Lavialle S, Lhermitte L, Suarez F, et al. Mast cell leukemia: identification of a new c-Kit mutation, dup(501–502), and response to masitinib, a c-Kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Eur J Haematol. 2012;89(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spector MS, Iossifov I, Kritharis A, et al. Mast-cell leukemia exome sequencing reveals a mutation in the IgE mast-cell receptor β chain and KIT V654A. Leukemia. 2012;26(6):1422–1425. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstovsek S. Advanced systemic mastocytosis: the impact of KIT mutations in diagnosis, treatment, and progression. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(2):89–98. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beghini A, Cairoli R, Morra E, et al. In vivo differentiation of mast cells from acute myeloid leukemia blasts carrying a novel activating ligand-independent C-kit mutation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1998;24(2):262–270. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotlib J, Berubé C, Growney JD, et al. Activity of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412 in a patient with mast cell leukemia with the D816V KIT mutation. Blood. 2005;106(8):2865–2870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae MH, Kim HK, Park CJ, et al. A case of systemic mastocytosis associated with acute myeloid leukemia terminating as aleukemic mast cell leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33(2):125–129. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horny HP, Parwaresch MR, Kaiserling E, et al. Mast cell sarcoma of the larynx. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39(6):596–602. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.6.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krauth MT, Födinger M, Rebuzzi L, et al. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis with sarcoma-like growth in the skeleton, leukemic progression, and partial loss of mast cell differentiation antigens. Haematologica. 2007;92(12):e126–e129. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valent P, Samorapoompichit P, Sperr WR, et al. Myelomastocytic leukemia: myeloid neoplasm characterized by partial differentiation of mast cell-lineage cells. Hematol J. 2002;3(2):90–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sperr WR, Drach J, Hauswirth AW, et al. Myelomastocytic leukemia: evidence for the origin of mast cells from the leukemic clone and eradication by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6787–6792. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arredondo AR, Gotlib J, Shier L, et al. Myelomastocytic leukemia versus mast cell leukemia versus systemic mastocytosis associated with acute myeloid leukemia: a diagnostic challenge. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(8):600–606. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valent P, Spanblöchl E, Bankl HC, et al. Kit ligand/mast cell growth factor-independent differentiation of mast cells in myelodysplasia and chronic myeloid leukemic blast crisis. Blood. 1994;84(12):4322–4332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wimazal F, Sperr WR, Horny HP, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis in a case of myelodysplastic syndrome with leukemic spread of mast cells. Am J Hematol. 1999;61(1):66–77. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199905)61:1<66::aid-ajh12>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(6):435–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escribano L, Diaz-Agustin B, López A, et al. Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) Immunophenotypic analysis of mast cells in mastocytosis: When and how to do it. Proposals of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2004;58(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tefferi A, Levine RL, Lim KH, et al. Frequent TET2 mutations in systemic mastocytosis: clinical, KITD816V and FIP1L1-PDGFRA correlates. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):900–904. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson TM, Maric I, Simakova O, et al. Clonal analysis of NRAS activating mutations in KIT-D816V systemic mastocytosis. Haematologica. 2011;96(3):459–463. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.031690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwaab J, Schnittger S, Sotlar K, et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013;122(14):2460–2466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horny HP, Parwaresch MR, Lennert K. Bone marrow findings in systemic mastocytosis. Hum Pathol. 1985;16(8):808–814. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horny HP, Sillaber C, Menke D, et al. Diagnostic value of immunostaining for tryptase in patients with mastocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(9):1132–1140. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horny HP, Valent P. Diagnosis of mastocytosis: general histopathological aspects, morphological criteria, and immunohistochemical findings. Leuk Res. 2001;25(7):543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(01)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horny HP, Sotlar K, Stellmacher F, et al. The tryptase positive compact round cell infiltrate of the bone marrow (TROCI-BM): a novel histopathological finding requiring the application of lineage specific markers. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(3):298–302. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.028738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krokowski M, Sotlar K, Krauth MT, et al. Delineation of patterns of bone marrow mast cell infiltration in systemic mastocytosis: value of CD25, correlation with subvariants of the disease, and separation from mast cell hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(4):560–568. doi: 10.1309/CX45R79PCU9HCV6V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sotlar K, Horny HP, Simonitsch I, et al. CD25 indicates the neoplastic phenotype of mast cells: a novel immunohistochemical marker for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis (SM) in routinely processed bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(10):1319–1325. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138181.89743.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jordan JH, Walchshofer S, Jurecka W, et al. Immunohistochemical properties of bone marrow mast cells in systemic mastocytosis: evidence for expression of CD2, CD117/Kit, and bcl-x(L) Hum Pathol. 2001;32(5):545–552. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.24319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horny HP, Greschniok A, Jordan JH, et al. Chymase expressing bone marrow mast cells in mastocytosis and myelodysplastic syndromes: an immunohistochemical and morphometric study. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(2):103–106. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valent P, Blatt K, Eisenwort G, et al. FLAG-induced remission in a patient with acute mast cell leukemia (MCL) exhibiting t(7;10)(q22;q26) and KIT D816H. Leuk Res Reports. 2014;3:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Dongen JJ, Lhermitte L, Böttcher S, et al. EuroFlow Consortium (EU-FP6, LSHB-CT-2006-018708) EuroFlow antibody panels for standardized n-dimensional flow cytometric immunophenotyping of normal, reactive and malignant leukocytes. Leukemia. 2012;26(9):1908–1975. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prokocimer M, Polliack A. Increased bone marrow mast cells in preleukemic syndromes, acute leukemia, and lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75(1):34–38. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/75.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varma N, Varma S, Wilkins B. Acute myeloblastic leukemia with differentiation to myeloblasts and mast cell blasts. Br J Haematol. 2000;111(4):991. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiu A, Orazi A. Mastocytosis and related disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2012;29(1):19–30. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gotlib J, Pardanani A, Akin C, et al. International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) & European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) consensus response criteria in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013;121(13):2393–2401. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-458521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]