Abstract

Background

Minocycline, a semi-synthetic tetracycline antibiotic, is an effective neuroprotective agent in animal models of cerebral ischemia when given in high doses intraperitoneally. The aim of this study was to determine if minocycline was effective at reducing infarct size in a Temporary Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion model (TMCAO) when given at lower intravenous (IV) doses that correspond to human clinical exposure regimens.

Methods

Rats underwent 90 minutes of TMCAO. Minocycline or saline placebo was administered IV starting at 4, 5, or 6 hours post TMCAO. Infarct volume and neurofunctional tests were carried out at 24 hr after TMCAO using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) brain staining and Neurological Score evaluation. Pharmacokinetic studies and hemodynamic monitoring were performed on minocycline-treated rats.

Results

Minocycline at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg IV was effective at reducing infarct size when administered at 4 hours post TMCAO. At doses of 3 mg/kg, minocycline reduced infarct size by 42% while 10 mg/kg reduced infarct size by 56%. Minocycline at a dose of 10 mg/kg significantly reduced infarct size at 5 hours by 40% and the 3 mg/kg dose significantly reduced infarct size by 34%. With a 6 hour time window there was a non-significant trend in infarct reduction. There was a significant difference in neurological scores favoring minocycline in both the 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg doses at 4 hours and at the 10 mg/kg dose at 5 hours. Minocycline did not significantly affect hemodynamic and physiological variables. A 3 mg/kg IV dose of minocycline resulted in serum levels similar to that achieved in humans after a standard 200 mg dose.

Conclusions

The neuroprotective action of minocycline at clinically suitable dosing regimens and at a therapeutic time window of at least 4–5 hours merits consideration of phase I trials in humans in view of developing this drug for treatment of stroke.

Background

Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic with demonstrated anti-inflammatory [1-3], glutamate antagonist [3,4], and anti-apoptotic actions [5-8] in many models of brain injury [2,3,9-11]. These properties, along with its superior human safety and blood-brain-barrier penetration make it an ideal candidate for clinical trials in stroke and other neurological diseases [12]. In focal cerebral ischemia, minocycline has been shown to reduce infarct size by more than 50% when administered up to 4 hours after the onset of ischemia in a rodent model [3,11,13]. However, the minocycline doses used in these studies were almost 30 times the weight-based dose routinely administered to humans for anti-infective and anti-inflammatory purposes [14].

Before translation of experimental stroke results to clinical trials in stroke patients can occur, a better understanding of the effective intravenous doses and the therapeutic window of minocycline must be obtained. The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether doses of minocycline which result in serum levels compatible with human administration, are effective in experimental cerebral ischemia. In addition, this study explored whether such dosing regimens of minocycline could confer neuroprotection at a therapeutic window of at least 4 hours after the onset of ischemia.

Methods

All the procedures were performed according to an institutional protocol and adhered to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) guidelines.

Temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (TMCAO) model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 270 to 330 gm were used for our studies. Rats were anesthetized with gas inhalation composed of 30% oxygen (0.3 L/ min) and 70% nitrous oxide (0.7 L/min) mixture. The gas was passed through an isoflurane vaporizer set to deliver 3% to 4% isoflurane during initial induction and 1.5% to 2% during surgery. An incision of the skin was made on top of the right common carotid artery region. The fascia was then blunt dissected until the bifurcation of the external carotid artery and internal carotidartery was isolated. A small incision was made on the external carotid artery, and a 19 to 22 mm long segment (depending on the weight of the animals) of 3–0 monofilament Nylon suture with a round tip was threaded into the internal carotid artery via the external carotid artery. The suture was advanced toward the middle cerebral artery (MCA) region to create focal ischemia. The suture was maintained in the vessel for 90 min then removed for reperfusion. Body temperature was maintained with a heating pad during surgery and during recovery from anesthesia.

Intravenous (IV) administration of minocycline

A volume of 1 ml solution per 100 g body weight was given intravenously to all animals. Three solutions used in the study were: minocycline 1 mg/ml in saline, minocycline 0.3 mg/ml in saline, and saline alone. The corresponding dosages were 10 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg minocycline hydrochloride (Sigma, USA) or saline alone respectively. The solutions were administered and repeated slowly through jugular vein injection (lasting for 5 min) at three different administration protocols after TMCAO: for the 4 hour post TMCAO protocol 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg was given at 4, 8, and 12 hr; for the 5 hour post-TMCAO protocol at 5, 9, and 13 hr; and for the 6 hour post TMCAO protocol at 6, 10, and 14 hr.

Hemodynamic monitoring

Intensive monitoring of hemodynamic parameters was measured in animals undergoing TMCAO. The arterial blood pressure and heart rate were measured through a right femoral artery PE50 tubing using a PowerLab/400 data acquisition system and analyzed using PowerLab software (ADInstruments, CO, USA) according to the manufacturer's specification.

Femoral arterial blood samples of 0.3 ml each were directly drawn into a 1 ml syringe with a #25 gauge needle and analyzed for pH, oxygen (pO2) and carbon dioxide (pCO2) using a Roche OPTI CCA E-Glu Cassette (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, IN, USA) and an OPTI Critical Care Analyzer (AVL Scientific Corporation, Georgia, USA). These parameters and rectal temperature (using Homeothermic Blanket Systems, Harvard Apparatus, MA, USA) were studied at 10 min before TMCAO, 90 min, 240 min, and 360 min after reperfusion in rats with 90 min TMCAO and Minocycline (10 mg/kg, IV, at 4 hr after TMCAO) or saline (3 ml, iv, at 4 hr after TMCAO) treatments.

Pharmacokinetic studies

In 18 animals that did not undergo TMCAO, (6 animals received either 3, 10, or 20 mg/kg of minocycline intravenously), blood samples (1 mL) were drawn from the jugular vein at 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes and 180 minutes after minocycline administration for assessment of maximum serum concentration (Cmax). After the samples were allowed to clot, serum was aspirated and frozen at -20 degrees Celsius until assayed.

Assay procedures

Minocycline was assayed using a reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatographic method based on that developed by Orti et al[15]. Sensitivity of the method was 1 mg/L. Standard curves were linear over the range of 1 to 75 mg/L.

Infarct size

Infarct volume was measured using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) stained brain slices (24 hr after TMCAO). This method provides an overall measure of cell injury presented by depleted NADPH and hence the inability to reduce TTC to its colored form.

Neurological score

Neurological deficits were examined at 24 hr after TMCAO just prior to sacrificing the animals using a 5-point scale adapted and modified from Zhang et al [16]. Specifically, no neurological deficit, 0 point; right Horner's syndrome, failure to extend left forelimb, hindlimb, turning to left and circling to left, each scored 1 point.

Statistical analyses

Two-group, repeated measures ANOVA were used to examine differences in seven physiologic measurements: blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, pH, PO2, PCO2, and glucose. Six animals were used in each of two treatment groups: Minocycline or saline at 4 hours following TMCAO. Measurements were made for each physiologic parameter at 10 minutes before TMCAO, and 90, 240 and 360 minutes following reperfusion. In each ANOVA model, animal nested within treatment group was considered a random effect. Fixed effects included the treatment group and time of measurement. As well, the two-factor interaction between treatment group and time was included in each model.

Two-factor ANOVA was used to examine differences between treatment groups and administration times for the proportion infarct size and neurological score. In each model, treatment group (3 mg/kg minocycline, 10 mg/kg minocycline, or saline) and administration time (4, 5, or 6 hours) follow TMCAO were considered as fixed effects. The two-factor interaction between treatment group and administration time was also included in each model. All statistical significance was assessed using an alpha level of 0.05. Post hoc tests comparing the 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg to saline within each administration time (i.e. 6 comparisons) were conducted using a Bonferroni correction to the overall alpha level.

Results

Pharmacokinetic

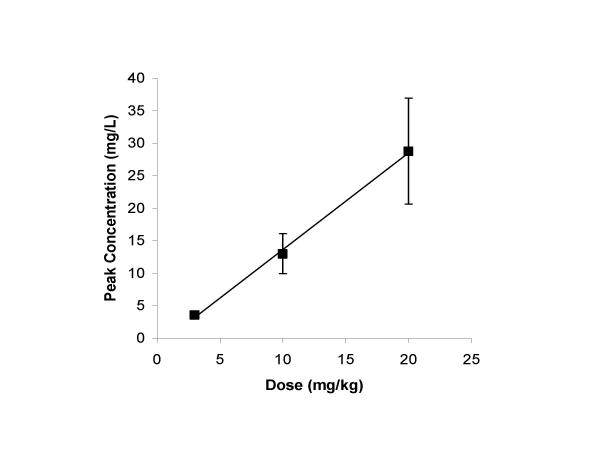

A linear relationship was observed between peak concentration and dose over the dose range studied (r = 0.998, Figure 1). Peak concentrations averaged 3.6, 13.0 and 28.8 mg/L with 3, 10 and 20 mg/kg doses respectively. The serum levels of MC at a 3 mg/kg dose (3.6 mg/L) were similar to that reported in humans after a standard 200 mg dose [14].

Figure 1.

Serum Levels of Minocycline. A linear relationship was observed between peak concentration and dose over the dose range studied (r = 0.998).

Physiological monitoring

The results for the repeated measures ANOVA model for each outcome are given in Table 1. For each outcome, differences between treatment groups within time period and differences between time period within treatment group were examined using the adjusted least square means of the two-factor interaction between treatment group and time. There were no statistically significant differences between the minocycline or saline groups within any time point for any of the outcome measures: blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, pH, PO2, PCO2, or glucose.

Table 1.

Adjusted least square means by treatment and time from the two-group, repeated measures ANOVA model results.

| Outcome | Minocycline | Saline | ||||||||||||||

| 10' | 90' | 240' | 360' | 10' | 90' | 240' | 360' | |||||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Blood Pressure | 102.33 | 2.68 | 102.50 | 2.68 | 102.00 | 2.68 | 100.00 | 2.68 | 113.17 | 2.68 | 102.83 | 2.68 | 101.33 | 2.68 | 98.67 | 2.68 |

| Heart Rate | 335.00 | 14.36 | 364.33 | 14.36 | 342.67 | 14.36 | 368.67 | 14.36 | 340.50 | 14.36 | 332.00 | 14.36 | 322.83 | 14.36 | 326.50 | 14.36 |

| Temperature | 36.87 | 0.07 | 37.02 | 0.07 | 37.05 | 0.07 | 37.08 | 0.07 | 37.17 | 0.07 | 37.00 | 0.07 | 36.93 | 0.07 | 37.00 | 0.07 |

| pH | 7.45 | 0.01 | 7.43 | 0.01 | 7.43 | 0.01 | 7.45 | 0.01 | 7.45 | 0.01 | 7.44 | 0.01 | 7.44 | 0.01 | 7.45 | 0.01 |

| P02 | 115.83 | 4.84 | 115.83 | 4.84 | 114.83 | 4.84 | 110.67 | 4.84 | 121.00 | 4.84 | 124.67 | 4.84 | 117.17 | 4.84 | 117.50 | 4.84 |

| PC02 | 43.17 | 0.87 | 43.66 | 0.87 | 44.50 | 0.87 | 43.17 | 0.87 | 44.17 | 0.87 | 44.00 | 0.87 | 43.83 | 0.87 | 44.17 | 0.87 |

| Glucose | 176.00 | 8.37 | 186.33 | 8.37 | 202.33 | 8.37 | 178.67 | 8.37 | 186.00 | 8.37 | 220.67 | 8.37 | 209.50 | 8.37 | 200.17 | 8.37 |

There were no statistically significant differences between the Minocycline or saline groups within any time point for any of the outcome measures

Infarct size

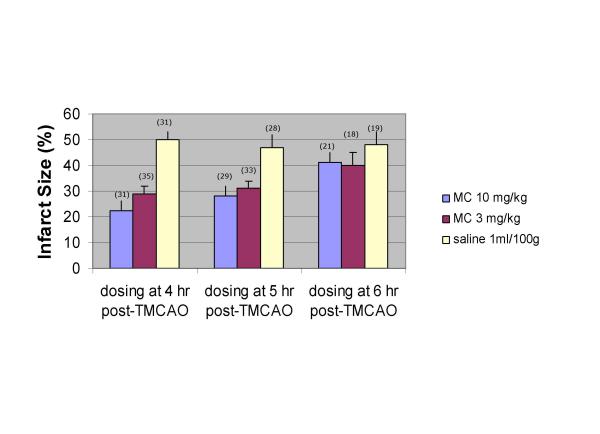

Minocycline at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg IV was effective at reducing infarct size at 4 hours post TMCAO (figure 2). At doses of 3 mg/kg, minocycline reduced infarct size by 42% while 10 mg/kg reduced infarct size by 56% at 24 hours. Minocycline at a dose of 10 mg/kg significantly reduced infarct size at 5 hours by 40% and the 3 mg/kg dose significantly reduced infarct size by 34%. With a 6 hour time window there was a non-significant trend in infarct reduction (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of MC IV dosing on infarct size at 24 hr after 90 min TMCAO. The post hoc tests for the proportion infarct size showed that within the 4-hour administration time, the 3 mg/kg (p = 0.0001) and 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0001) minocycline groups had significantly lower mean proportion infarct size than the saline group. At the 5-hour administration time, the 3 mg/kg (p = 0.0010) and 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0002) minocycline groups had significantly lower mean proportion infarct size than the saline group. There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion infarct size between treatment groups at the 6-hour administration time window * the number atop the bar figure was the animal numbers of that group.

Neurological score

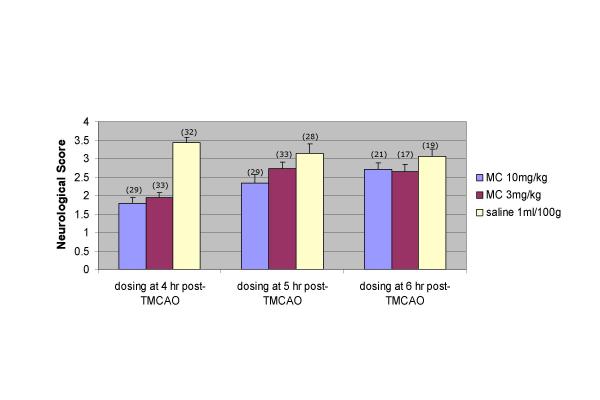

Examination of neurological function indicated that there was a significant amelioration of neurological deficits in animals that received 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg Iv minocycline at 4 hours post TMCAO compared to animals that received saline placebo. A signficant improvement in neurological scores was evident in the 10 mg/kg but not the 3 mg/kg dose compared to placebo at 5 hours. No significant differences in the neurological scores were seen at the 6 hour time windows (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of MC IV dosing on neurofunction at 24 hr after 90 min TMCAO. For the neurological score a statistically significant interaction between treatment group and administration time was detected. Within the 4-hour time window, the saline group had significantly higher neurological scores than the 3 mg/kg (p = 0.0001) and 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0001) minocycline groups. Within the 5-hour time window, the saline group had significantly higher neurological scores than the 10 mg/kg minocycline group (p = 0.0003), but the 3 mg/kg minocycline group was not statistically different (p = 0.0669). There were no statistically significant differences in neurological scores at the 6-hour administration window. * the number atop the bar figure was the animal numbers of that group.

Discussion

Minocycline has been shown to be neuroprotective in a variety of animal models of both chronic neurodegeneration and acute CNS injury. Besides acute ischemic stroke, minocycline is effective in rodent models of intracerebral hemorrhage [17] and spinal cord injury [18]. However, the doses used in the acute CNS injury studies have been high (44–90 mg/kg) and it is not clear if lower doses that have been shown to be safe in humans will have a similar neuroprotective effect. Moreover, in all the studies published to date, minocycline has been administered by intraperitoneal (IP) or oral route. We have recently shown that IP administration of minocycline in rodents leads to delayed and erratic absorption and peritoneal irritation [19].

While oral dosing is preferred in chronic neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the intravenous route is preferred to rapidly achieve targeted serum and CNS levels in acute neurological disorders such as ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, spinal cord injury, and traumatic brain injury. In this study, IV minocycline at doses that likely are safe in humans (3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg) reduced infarct size in a TMCAO model. The dose of 3 mg/kg resulted in serum levels similar to those reported in humans given a corresponding dose [14]. The standard human dose of minocycline is 200 mg, roughly equivalent to the 3 mg/kg dose found to reduce infarct size with a time window of 4 hours in our TMCAO model. Doses of 400 mg of minocycline appear to be safe in humans but there is limited safety data available on higher doses. Moreover, there is also no safety data on minocycline administered to patients with acute ischemic stroke. Minocycline did not have an effect on important physiological variables such as blood pressure, pO2, pCO2 or glucose in our animals undergoing TMCAO.

Clinical trials of neuroprotective agents in acute stroke have failed [20]. One of the important reasons for these failures is administering a drug in humans beyond the time window when it is effective in rodents. Importantly, the therapeutic time window for both 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg of minocycline was 4–5 hours. This time window would extend a potential therapeutic benefit to many stroke patients. Since it is relatively easy to administer, minocycline could be administered to stroke patients in smaller community hospitals and even by Emergency Medical Personnel in the field. Our studies and the known favorable safety profile of minocycline indicate that minocycline may be an effective agent in acute ischemic stroke and supports initiation of phase I trials of minocycline.

Conclusion

Minocycline at a dose of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg IV is effective at reducing infarct size with a 5 hour therapeutic time window after TMCAO. With a dose of 10 mg/kg the window to ameliorate neurological deficits is extended to 5 hours. Phase I trials of IV minocycline in acute ischemic stroke should be initiated.

List of abbreviations

Intravenously (IV); Temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (TMCAO);

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

XL carried out all in vivo studies, participated in the design of the study and contributed to manuscript preparation. SCF assisted in the design of the study, reviewed all data, and assisted in writing the manuscript. JW performed all the statistical analyses. DJE performed all the pharmacokinetic studies. CB assisted in the design of the trial and in the animal protocols. JZ assisted with the analysis of the infarct size and the neurological testing. WDH helped with design and manuscript preparation. GF assisted in the design of the trial, reviewed the data, and provided consultation. DCH helped design the study and participated in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Funded by:

This work was supported by grants from NINDS (1U01NS43127-01 and RO1NS044216-01 – SF) and the American Heart Association Southeast Affiliate (SCF and CVB) and from VA Merit Review (DCH) and VA Career Development Award (CVB)

Marc Handelsman, Ankur Arora, and Berthia Gainer provided technical assistance

Contributor Information

Lin Xu, Email: lxu@mail.mcg.edu.

Susan C Fagan, Email: sfagan@mail.mcg.edu.

Jennifer L Waller, Email: jwaller@mail.mcg.edu.

David Edwards, Email: aa1344@wayne.edu.

Cesar V Borlongan, Email: cborlongan@mail.mcg.edu.

Jianqing Zheng, Email: jzheng@mail.mcg.edu.

William D Hill, Email: whill@mail.mcg.edu.

Giora Feuerstein, Email: giora_feuerstein@merck.com.

David C Hess, Email: dhess@mail.mcg.edu.

References

- Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Tieu K, Teismann P, Vadseth C, Choi DK, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S. Blockade of microglial activation is neuroprotective in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1763–1771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01763.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yrjanheikki J, Keinanen R, Pellikka M, Hokfelt T, Koistinaho J. Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global brain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15769–15774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yrjanheikki J, Tikka T, Keinanen R, Goldsteins G, Chan PH, Koistinaho J. A tetracycline derivative, minocycline, reduces inflammation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia with a wide therapeutic window. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13496–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikka TM, Koistinaho JE. Minocycline provides neuroprotection against N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglia. J Immunol. 2001;166:7527–7533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvin KL, Han BH, Du Y, Lin SZ, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Minocycline markedly protects the neonatal brain against hypoxic-ischemic injury. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:54–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander RM. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu S, Drozda M, Zhang W, Stavrovskaya IG, Cattaneo E, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits caspase-independent and -dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways in models of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10483–10487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832501100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, Sarang S, Liu AS, Hartley DM, Wu du C, Gullans S, Ferrante RJ, Przedborski S, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz J, Nguyen MD, Julien JP. Minocycline slows disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:268–278. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Yune TY, Kim SJ, Park do W, Lee YK, Kim YC, Oh YJ, Markelonis GJ, Oh TH. Minocycline reduces cell death and improves functional recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1017–1027. doi: 10.1089/089771503770195867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CX, Yang T, Shuaib A. Effects of minocycline alone and in combination with mild hypothermia in embolic stroke. Brain Res. 2003;963:327–329. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)04045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravina BM, Fagan SC, Hart RG, Hovinga CA, Murphy DD, Dawson TM, Marler JR. Neuroprotective agents for clinical trials in Parkinson's disease: a systematic assessment. Neurology. 2003;60:1234–1240. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058760.13152.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CX, Yang T, Noor R, Shuaib A. Delayed minocycline but not delayed mild hypothermia protects against embolic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2002;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saivin S, Houin G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of doxycycline and minocycline. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;15:355–366. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198815060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orti V, Audran M, Gibert P, Bougard G, Bressolle F. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay for minocycline in human plasma and parotid saliva. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2000;738:357–365. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(99)00547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RL, Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q, Ewing JR. A rat model of focal embolic cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1997;766:83–92. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Henry S, Del Bigio MR, Larsen PH, Corbett D, Imai Y, Yong VW, Peeling J. Intracerebral hemorrhage induces macrophage activation and matrix metalloproteinases. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:731–742. doi: 10.1002/ana.10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JE, Hurlbert RJ, Fehlings MG, Yong VW. Neuroprotection by minocycline facilitates significant recovery from spinal cord injury in mice. Brain. 2003;126:1628–1637. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan SC, Edwards DJ, Borlongan CV, Xu L, Arora A, Feuerstein G, Hess DC. Optimal delivery of minocycline to the brain: implication for human studies of acute neuroprotection. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell CS, Liebeskind DS, Starkman S, Saver JL. Trends in acute ischemic stroke trials through the 20th century. Stroke. 2001;32:1349–1359. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]