Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the hepatotoxicity of timosaponin A3 (TA3), a steroidal saponin from Anemarrhena asphodeloides, in rats.

Methods:

Male SD rats were administered TA3 (100 mg·kg−1·d−1, po) for 14 d, and the blood and bile samples were collected after the final administration. The viability of a sandwich configuration of cultured rat hepatocytes (SCRHs) was assessed using WST-1. Accumulation and biliary excretion index (BEI) of d8-TCA in SCRHs were determined with LC-MS/MS. RT-PCR and Western blot were used to analyze the expression of relevant genes and proteins. ROS and ATP levels, and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were measured. F-actin cytoskeletal integrity was assessed under confocal microscopy.

Results:

TA3 administration in rats significantly elevated the total bile acid in serum, and decreased bile acid (BA) component concentrations in bile. TA3 inhibited the viability of the SCRHs with an IC50 value of 15.21±1.73 μmol/L. Treatment of the SCRHs with TA3 (1–10 μmol/L) for 2 and 24 h dose-dependently decreased the accumulation and BEI of d8-TCA. The TA3 treatment dose-dependently decreased the expression of BA transporters Ntcp, Bsep and Mrp2, and BA biosynthesis related Cyp7a1 in hepatocytes. Furthermore, the TA3 treatment dose-dependently increased ROS generation and HO-1 expression, decreased the ATP level and MMP, and disrupted F-actin in the SCRHs. NAC (5 mmol/L) significantly ameliorated TA3-induced effects in the SCRHs, whereas mangiferin (10–200 μg/mL) almost blocked TA3-induced ROS generation.

Conclusion:

TA3 triggers liver injury through inducing ROS generation and suppressing the expression of BA transporters. Mangiferin, an active component in Anemarrhena, may protect hepatocytes from TA3-induced hepatotoxicity.

Keywords: timosaponin A3, hepatotoxicity, cholestasis, bile acid, transporter, Cyp7a1, ROS, N-acetyl-L- cysteine, mangiferin

Introduction

Hepatotoxicity is a significant adverse event in drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Cholestasis represents a frequent manifestation of DILI in humans, and it has an important function during the pathologic process. It is characterized by impaired hepatocellular secretion of bile and results in the accumulation of bile acids (BAs), bilirubin, and cholesterol in the liver1. In many cases, cholestasis is due to alterations in hepatobiliary transporter system, particularly the sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (Ntcp or Slc10a1) and the bile salt export pump (Bsep or Abcb11), which are the most essential transporters of BA2. The hepatic uptake and efflux of BAs are also mediated by other transporters, such as the organic anion transporting polypeptide (Oatp) and the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (Mrp2), which are responsible for taking up conjugated and unconjugated BAs into hepatocytes and pumping divalent BAs into the bile canaliculi, respectively3,4.

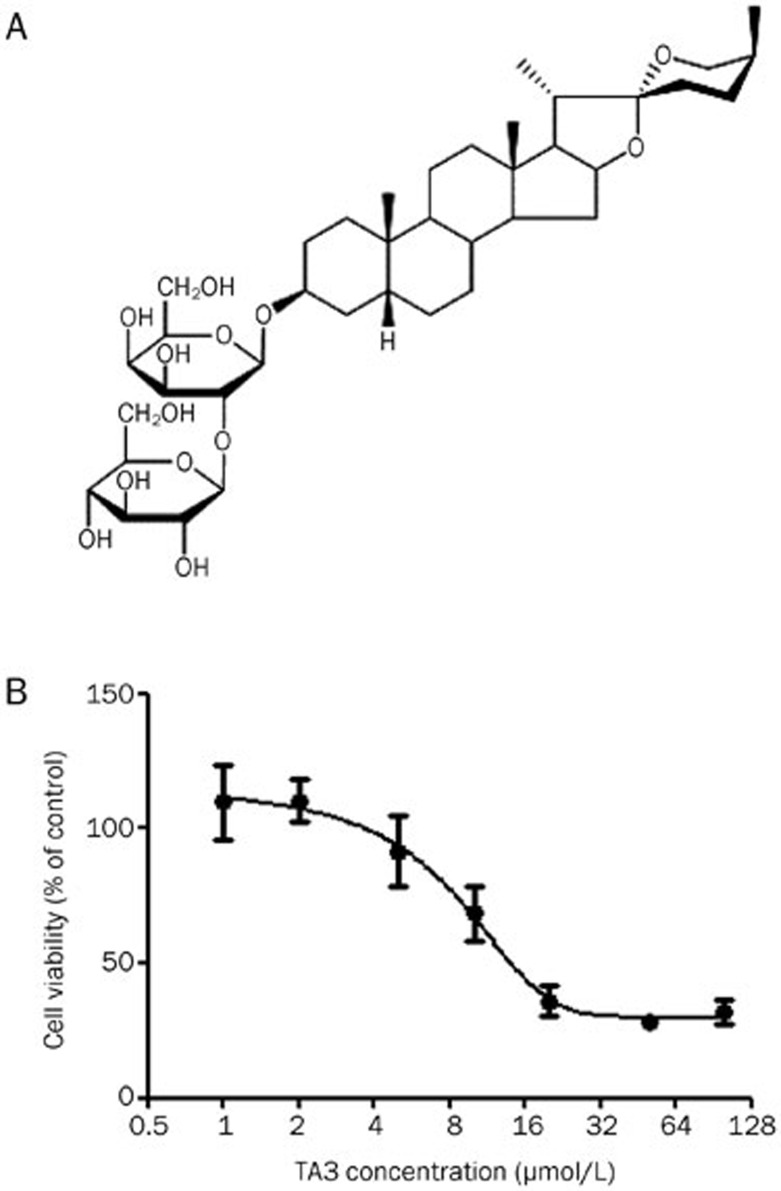

Timosaponin A3 (TA3, Figure 1A), one of the major steroidal saponin components isolated from Anemarrhena asphodeloides, displays promising pharmacological activity in improving learning, memory, and antineoplastic activity5,6. Our group recently found that TA3 had a very high concentration in rat liver after a single oral administration7, and in an acute toxicity study, rat liver showed extensive ballooning degeneration and vacuolization (Figure S1). This acute toxicity may prevent the efforts to develop TA3 into a drug candidate if the mechanism of toxicity remains unclear. Although Anemarrhena asphodeloides and its extractions have been widely used medically for thousands of years, there have been no reports of its hepatoxicity8. Additionally, no previous studies have detailed the toxicity of the Anemarrhena asphodeloides extract in rats. To assess the significance of this observation and understand the mechanism of potential liver damage induced by TA3, we examined the connections between TA3-induced hepatotoxicity and cholestasis.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of TA3 and TA3-induced cytotoxicity. (A) The chemical structure of TA3. (B) Cell viability in sandwich-cultured rat hepatocytes (SCRHs) after TA3 treatment. The hepatocytes were treated with TA3 or vehicle for 24 h. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=6).

Transporters play a critical role in cholestasis; our group has reported that toxicants may induce cholestasis by inhibiting BA transporter functions in sandwich-cultured rat hepatocytes (SCRHs)9. The same strategy was employed here to investigate the hepatotoxicity of TA3.

In the present study, we investigated the cholestatic effect of TA3 in rats and SCRHs. The impact of TA3 on essential transporters and the integrity of hepatocytes was assessed. The protective role of antioxidants NAC and mangiferin (one of the active compounds of Anemarrhena asphodeloides) against TA3-induced oxidative stress in hepatocytes was also examined.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

TA3 (purity ≥97%) and mangiferin (purity ≥95%) were extracted and purified at the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the reagents used in cell culture were obtained from GIBCO, unless otherwise stated.

Rat hepatocyte isolation and culture

Rat hepatocytes were obtained via a two-step collagenase digestion method with modification10. In brief, cell viability was >85%, as determined by trypan blue exclusion. Isolated hepatocytes were seeded in culture plates coated with collagen-I and allowed to attach for 4 h in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 before the medium was changed. After 24 h, cells were overlaid with 0.25 mg/mL Matrigel (Palo Alto, CA, USA) in FBS-free, ice-cold medium. A sandwich configuration was formed during the following culture period as previously described11. All the following cell experiments were conducted using the sandwich culture system at 24 h after coating with Matrigel, unless otherwise stated.

WST-1 assay

Hepatocytes were seeded in 96-well plates (3×104 cells/well). Cultured hepatocytes were treated with TA3 (0–100 μmol/L) for 24 h. Cytotoxicity assays were performed after drug administration according to the WST-1 protocol (Beyotime, Haimen, China).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

Intracellular ROS production was assessed by the cellular conversion of DCFDA to 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCF)12. After incubation with TA3 or TA3+NAC/mangiferin for 24 h, the medium was aspirated, and the hepatocytes (in a black 96-well microplate) were preloaded with 5 μmol/L DCFDA (dissolved in HBSS) and incubated for 1 h. After the incubation period, the cells were washed once with PBS, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using a multi-well fluorescence plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 485 and 530 nm, respectively.

ATP assay

ATP levels in hepatocytes were determined using a CellTiter-GloTM Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Bioluminescence was measured by a microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, USA).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

The MMP was monitored using tetramethylrhodamine ethylester (TMRE, 1 μmol/L), a red-orange dye, according to methods described previously13. CCCP (20 μmol/L), a mitochondrial toxin, was used as a positive control14. CCCP was added to the control samples 15 min before adding TMRE. After incubation for 20 min with TMRE, the cells were washed once with 0.2% BSA in PBS, and fluorescence readings were obtained on a microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 549 and 575 nm, respectively.

BA (d8-TCA) uptake and biliary excretion in SCRHs

The uptake and biliary clearance of deuterium-labeled sodium taurocholate (d8-TCA, Martrex, Inc, Minnesota, USA) in SCRHs were determined according to the method described previously15 with slight modification. In brief, after incubation with TA3 or TA3+NAC for specific times (15 min, 2 h, and 24 h), SCRHs were rinsed two times with 300 μL of warm standard HBSS or Ca2+-free HBSS and pre-incubated with 300 μL of the same buffer at 37 °C for 15 min. After removing the buffer, the hepatocytes were incubated for 15 min with d8-TCA (1 μmol/L) in 300 μL of standard HBSS. After incubation, the solution was aspirated from the cells, uptake was terminated by washing three times with ice-cold PBS, and the samples were frozen for analysis. The biliary excretion index (BEI) was calculated as follows: BEI=[AHBSS–AHBSS (Ca2+free)]/AHBSS×100%, which was defined as the proportion of accumulated taurocholate excreted into bile canaliculi16, where AHBSS and AHBSS (Ca2+-free) represent the amount of accumulated d8-TCA in the standard buffer treatment wells (hepatocytes+bile) and calcium-free buffer treatment wells (hepatocytes), respectively.

BA (d8-TCA) accumulation in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes

BA accumulation assays were performed as previously described17,18 with slight modifications. Isolated hepatocytes were plated in 24-well plates. Once attached (4 h), the cells were washed twice with warmed standard HBSS (Na+ condition) or Na+-free choline buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, 5 mmol/L glucose, 5.4 mmol/L KCl, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.9 mmol/L MgSO4, 10 mmol/L HEPES, and 137 mmol/L choline). Subsequently, the hepatocytes were incubated with the uptake buffer for 10 min. After aspiration of the pre-incubation buffer, taurocholate uptake was initiated by the addition of 300 μL of standard HBSS or Na+-free choline buffer containing d8-TCA and TA3 at 37 °C for 15 min. Troglitazone (10 μmol/L) was selected as the positive control, as it inhibits d8-TCA uptake18. Finally, the accumulation of d8-TCA was terminated by washing the hepatocytes two times with ice-cold PBS, and the samples were frozen for analysis.

Gene expression measured by quantitative RT-PCR

After the treatment of TA3 or TA3+NAC in SCRHs for 24 h, total RNA was isolated from the hepatocytes with TRIzol reagent (Life Technology, CA, USA), and RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a Primescript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Gene expression levels were quantified using a real-time PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Primers for the Cyp7a1, Bsep, Mrp2, Ntcp, and β-actin genes were synthesized with the sequences listed in Table 1. β-Actin was used for internal normalization. The genes of interest were amplified using a Qiagen Roter Gene Q instrument (Qiagen).

Table 1. Sequence of primers for RT-PCR analysis. F, forward; R, reverse.

| Gene | Sequence (5′–3′) | Size (bp) | GenBank accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mrp2 F | GAAGGCATTGACCCTATCT | 318 | NM_012833.1 |

| Mrp2 R | CCACTGAGAATCTCATTCATG | ||

| Bsep F | ATGTTGGAACGGAGGAACTG | 205 | NM_031760.1 |

| Bsep R | CCTTCTCGACCCGATATTCA | ||

| Ntcp F | AGGCATGATCATCACCTTCC | 277 | NM_017047 |

| Ntcp R | AAGTGGCCCAATGACTTCAG | ||

| Cyp7a1 F | CACCATTCCTGCAACCTTTT | 170 | NM_012942.2 |

| Cyp7a1 R | GTACCGGCAGGTCATTCAGT | ||

| HO-1 F | CACGCATATACCCGCTACCT | 227 | NM_012580.2 |

| HO-1 R | AAGGCGGTCTTAGCCTCTTC |

Animal study

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (200±20 g) were obtained from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center Co, Ltd (Shanghai, China). The animals were housed in an air-conditioned room with a 12-h on and 12-h off light cycle, and they received powdered rodent chow and tap water by the bottle ad libitum. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The rats were used to isolate hepatocytes and for the following animal studies. During drug treatment, TA3 was suspended in a 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium solution (CMC-Na+) and administered by oral gavage in a volume of 10 mL/kg body weight at dose levels of 100 mg/kg for fourteen consecutive days. The controls received the same volume of vehicle. After the final administration of TA3 or vehicle, the rats were fasted overnight and anesthetized with pentobarbital. Blood samples were collected from oculi chorioideae vein, and a polyethylene tube (Clay Adams, USA) was then inserted into the common bile duct for bile collection. All of the samples were stored at -80 °C until analysis.

Blood biochemistry

Serum for biochemistry analysis was obtained from rat blood samples. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total BA (TBA) were determined using an Automatic Clinical Analyzer (7080, HITACHI Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of biological samples

The d8-TCA concentration in hepatocytes was analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (LCMS-8030; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan)9. The data were normalized to the protein amount using a BCA protein assay (Rockford, IL, USA). The analysis of bile samples was performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity UPLC coupled to an Agilent 6460 Triple-Quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a JetStreamTM ESI source (Agilent Technologies, Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to a previous report19.

Confocal microscopy

F-actin was stained with phalloidin-FITC20 using a previously described method21. In brief, hepatocytes were seeded onto glass cover slips, fixed in 3% (w/v) formaldehyde for 20 min, washed three times using PBS, and permeabilized by soaking the coverslips in 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After washing three times in PBS, the cover slips were treated with a 5 μg/mL solution of FITC-phalloidin in PBS for 20 min. The cover slips were washed three times in PBS and mounted in 90% glycerol-PBS containing 2.5% (w/v) diazabicyclo[2,2,2]octane. The specimens were examined using laser-scanning fluorescence microscopy.

Western blotting

The total protein of hepatocytes was extracted by RIPA lysis buffer containing 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime, Haimen, China). The proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE. After transferring the proteins to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the membrane was blocked, incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed, incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h, washed again, and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Millipore, USA). β-Actin was selected as the internal control.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.03 software. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using Student's t-test. A one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test were used to test statistical significance among groups. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

TA3 induced hepatotoxicity in vitro and cholestasis in vivo

SCRHs were exposed to TA3 for 24 h in a 96-well plate, and cell viability was determined by the WST-1 assay. It was found that TA3 reduced cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B), and the IC50 was 15.21±1.73 μmol/L. Based on this result, in the following in vitro experiments, we used the concentration of TA3 below the IC50.

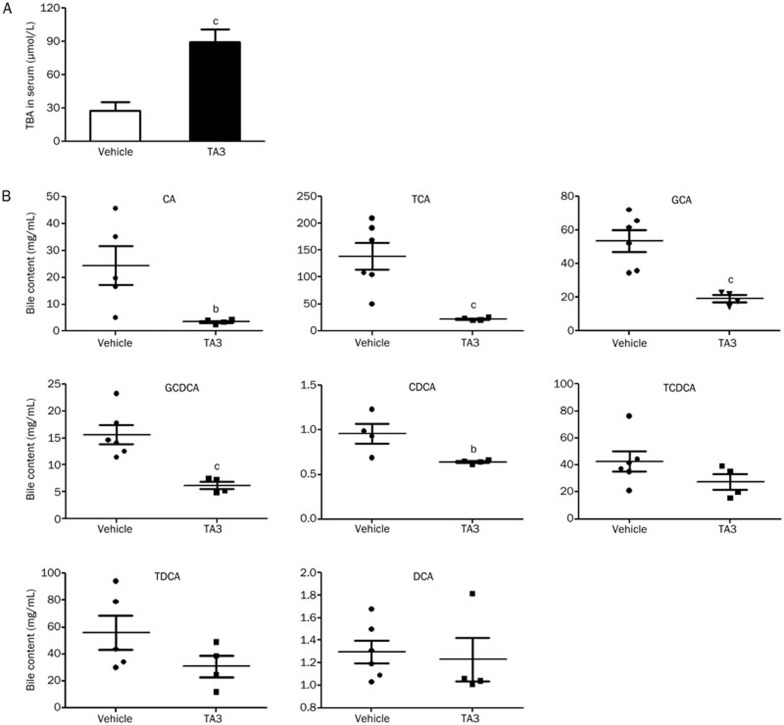

Male rats were administered 100 mg/kg TA3 daily for fourteen consecutive days (the dosage is 10% of the LD50, data not shown). Body weight loss was observed (Figure S2A), and the TBA and ALT in the serum of TA3-fed rats increased significantly compared with that in the vehicle-fed group (Figure 2A and Figure S2B). The measured concentrations of BA constituents (CA, TCA, GCA, GCDCA, CDCA, TCDCA, TDCA, and DCA) in bile decreased compared with those in the vehicle group after 14 d of TA3 administration (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

TA3-induced cholestasis and disrupted bile acids homeostasis in SD rats. (A) Changes in total BA levels in serum after TA3 administration at 100 mg/kg daily for 14 d. (B) The determination of 8 types of BA components (CA, TCA, GCA, GCDCA, CDCA, TCDCA, TDCA, and DCA) in bile. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=4–6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs vehicle.

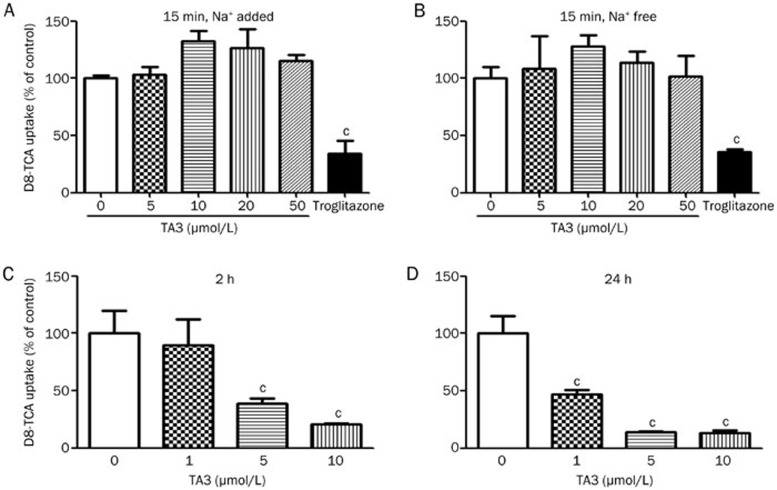

D8-TCA uptake and efflux in hepatocytes after TA3 treatment

After acute TA3 treatment (15 min), the uptake and BEI of d8-TCA in hepatocytes did not change significantly (Figure 3A, 3B, and Table 2). The uptake of d8-TCA in primary rat hepatocytes was assessed through the presence or absence of Na+ (Figure 3A, 3B). The accumulation of d8-TCA in hepatocytes was not impeded by TA3 in either case.

Figure 3.

The effects of TA3 on the accumulation of d8-TCA in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes and SCRHs. D8-TCA (1 μmol/L) uptake by rat hepatocytes at 15 min, 37 °C, co-incubated with TA3 (5, 10, 20, and 50 μmol/L) in Na+-added (A) and Na+-free (B) buffer. Troglitazone (10 μmol/L) was used as a positive control. SCRHs were incubated with d8-TCA (1 μmol/L) for 15 min after TA3 (1, 5, and 10 μmol/L) treatment for 2 h (C) and 24 h (D), and the concentration of d8-TCA was measured. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=4). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs vehicle.

Table 2. Effect of TA3 on the biliary excretion index (BEI) of d8-TCA in SCRHs. Data are expressed as the percentage of the control. Mean±SD. n=3. bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with the control.

| Treatment time | TA3 (μmol/L) | BEI (%) of d8-TCA | % of Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 0 | 60.0±6.0 | 100 |

| 1 | 60.6±7.8 | 101 | |

| 5 | 55.7±10.4 | 92 | |

| 10 | 56.6±2.0 | 95 | |

| 2 h | 0 | 72.3±4.0 | 100 |

| 1 | 71.5±6.0 | 99 | |

| 5 | 53.9±10.2b | 75 | |

| 10 | 17.8±2.1c | 25 | |

| 24 h | 0 | 74.4±3.2 | 100 |

| 1 | 64.7±4.3 | 87 | |

| 5 | 28.1±9.6c | 38 | |

| 10 | 15.1±11.0c | 20 |

After 2 and 24 h of incubation with TA3, the accumulation and biliary excretion of d8-TCA in SCRH significantly decreased (Figure 3C, 3D, and Table 2). The decrease in d8-TCA accumulation and biliary excretion after 24 h of TA3 treatment was greater than the reduction after 2 h.

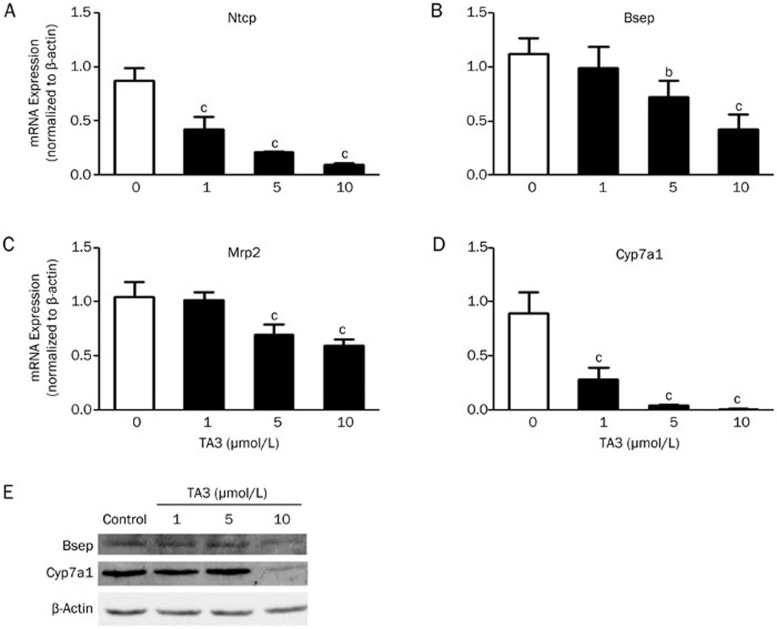

Effect of TA3 on BA-related transporters and synthesizing enzyme expression in SCRHs

TA3 significantly decreased the mRNA levels of the influx transporter Ntcp and efflux transporters Bsep and Mrp2. The BA-synthesizing enzyme Cyp7a1 was also downregulated by TA3 (Figure 4A–4D). Western blot analysis showed that the expression levels of Bsep and Cyp7a1 decreased (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

The mRNA and protein levels of genes involved in BA transport and synthesis measured by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis after TA3 (1, 5, and 10 μmol/L) treatment for 24 h. The expression levels of each gene were expressed as values normalized to β-actin expression. (A) Ntcp mRNA expression; (B) Bsep mRNA expression; (C) Mrp2 mRNA expression; (D) Cyp7a1 mRNA expression; (E) Expression of protein levels of Bsep and Cyp7a1. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs vehicle.

ROS generation and hepatotoxicity in TA3-treated SCRHs

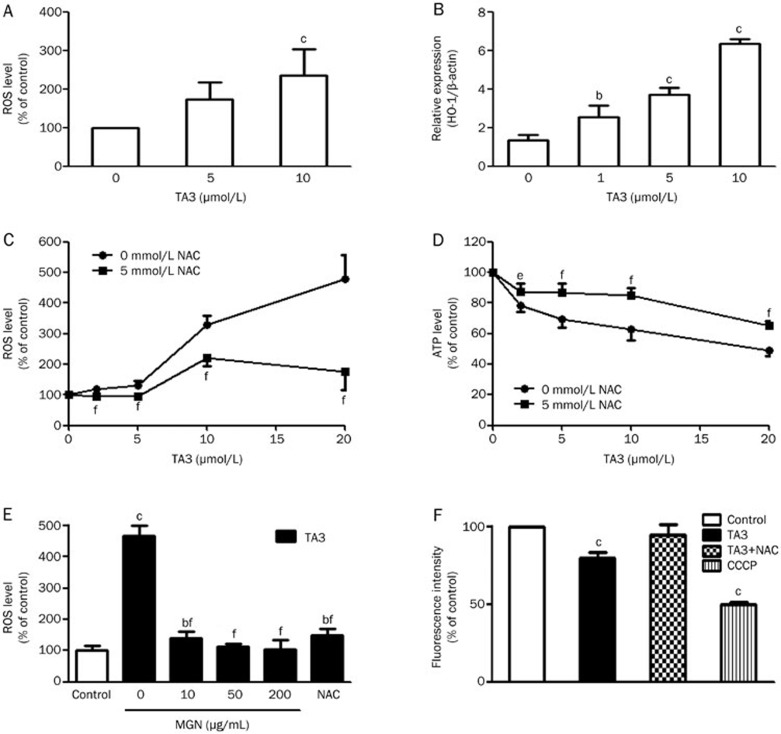

The ROS level of TA3-treated hepatocytes significantly increased compared with the vehicle-treated control hepatocytes (Figure 5A). The expression of oxidative stress-related genes (heme oxygenase 1, HO-1) in SCRHs dose-dependently increased after 24 h of TA3 treatment (Figure 5B). Compared with the TA3-treated cells, the amount of ROS generated in the TA3+NAC- or TA3+mangiferin-treated hepatocytes was significantly reduced. The ROS production level was almost declined to those in TA3 untreated controls (Figure 5C, 5E). The results of the ATP assay also indicated that NAC and mangiferin reduced TA3-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 5D and Figure S3B). A loss in MMP was observed in SCRHs treated with 5 and 10 μmol/L TA3 for 12 h; however, NAC pretreatment restored the MMP to normal levels (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

The impact of NAC or mangiferin on TA3-induced hepatotoxicity in SCRHs. (A) The ROS level was measured after TA3 (5 and 10 μmol/L) treatment for 8 h. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of HO-1 expression in hepatocytes treated with TA3 (1, 5, and 10 μmol/L) for 24 h. Cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mmol/L) and co-incubated with TA3 (1, 5, 10, and 20 μmol/L), then the ROS level (C) and ATP level (D) was measured. (E) The ROS level after pretreatment with mangiferin (10, 50, and 200 μg/mL) and NAC (5 mmol/L) for 2 h and co-incubated with TA3 (10 μmol/L) for 24 h. (F) The MMP level after pretreatment with NAC (5 mmol/L) for 2 h and co-incubation with TA3 (10 μmol/L) for 12 h. CCCP (20 μmol/L) was used as a positive control. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=5). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with the control. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 (TA3+NAC/mangiferin treatment vs TA3 alone).

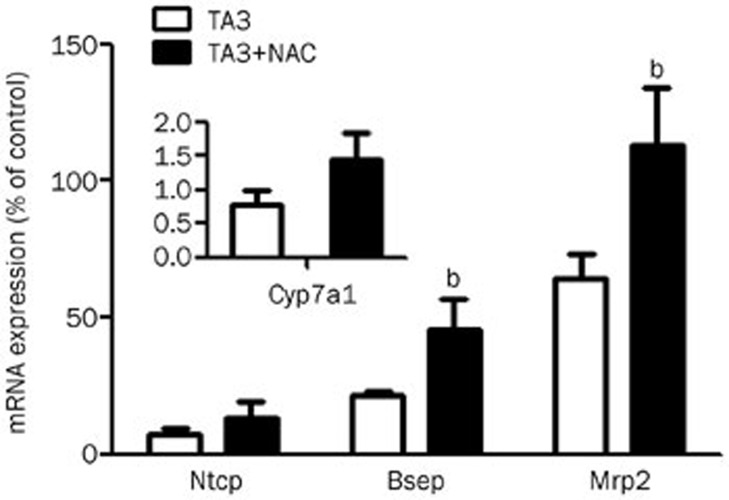

mRNA expression of Ntcp, Bsep, Mrp2, and Cyp7a1 in SCRHs treated with TA3 and NAC

RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the expression levels of the Ntcp, Bsep, Mrp2, and Cyp7a1 genes in response to TA3+NAC treatment were higher than those in SCRHs following TA3 treatment alone (Figure 6). Mrp2 expression nearly recovered to the level of the control group after co-incubation with NAC. The expression level of the Cyp7a1 gene considerably decreased compared with that of control even in the presence of NAC.

Figure 6.

NAC improved the expression of BA transporters and the synthesizing gene. Hepatocytes were pretreated with NAC (5 mmol/L) and co-incubated with TA3 (5 μmol/L) for 24 h. Cell samples were collected to isolate total RNA, and the gene was determined by RT-PCR. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 (TA3+NAC treatment vs TA3 alone).

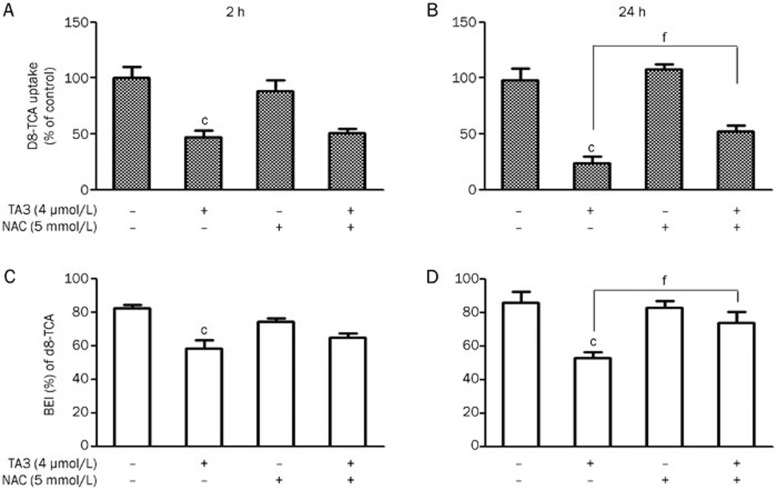

Assessment of BA basolateral transporter function in SCRHs treated with TA3 and NAC

The effect of NAC on d8-TCA uptake in SCRHs treated with TA3 was determined. The amounts of d8-TCA in SCRH were only 47.1%±6.0% and 24.2%±6.1% of those in the vehicle-treated control at 2 and 24 h (respectively) after TA3 treatment. NAC co-incubation with TA3 increased the d8-TCA concentrations in SCRHs to 57.0%±11.0% and 43.1%±2.2% at 2 and 24 h, respectively (Figure 7A, 7B).

Figure 7.

Effects of NAC on d8-TCA uptake and efflux in TA3-treated SCRH. Cells were incubated with d8-TCA (1 μmol/L) after treatment with TA3+NAC for 2 h (A) and 24 h (B), and d8-TCA accumulation was determined. D8-TCA efflux capacity was calculated as the BEI of d8-TCA. (C) BEI of d8-TCA after treatment for 2 h. (D) BEI of d8-TCA after treatment for 24 h. The data are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 vs vehicle. eP<0.05, fP<0.01 (TA3+NAC treatment vs TA3 alone).

The function of BA biliary excretion was also verified. The reduction in d8-TCA efflux activity by TA3 was time-dependent. In Figure 7C, the BEI of d8-TCA decreased by 29.0% after 2 h of TA3 treatment (BEI values decreased from 82.1%±2.2% to 58.1%±5.0%). The reduction decreased to 12.5% (BEI values: 74.3%±2.2% to 65.0%±2.5%) in the presence of NAC. When the incubation time was extended to 24 h, the BEI decreased by 36.0% (BEI values: 86.0%±6.2% to 54.9%±6.0%) in the TA3-treated group, whereas the BEI only slightly decreased by 9.0% (BEI values: 77.8%±5.4% to 71.0%±9.5%) when NAC was added (Figure 7D). This finding indicated that NAC could improve the function of BA canalicular membrane transporters impaired by TA3.

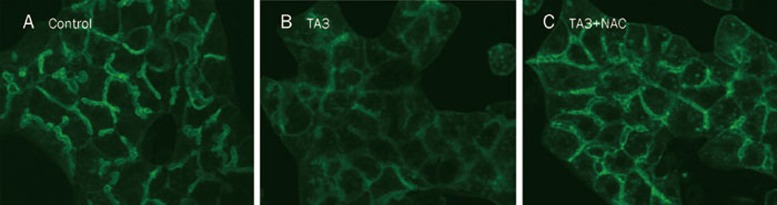

Disruption of the hepatocyte cytoskeleton protein F-actin after TA3 treatment in SCRHs

The effect of TA3 on F-actin in SCRHs was investigated. Upon TA3 treatment, the structure of the actin cytoskeleton was distinctly blurred compared with that in the vehicle control group, indicating F-actin disruption after TA3 treatment (Figure 8A, 8B). By contrast, when hepatocytes were co-treated with TA3 and NAC, the actin cytoskeleton partly recovered (Figure 8C), and the cells displayed normal cell morphology. This result suggests that NAC protected F-actin against TA3-induced disruption.

Figure 8.

Phalloidin-FITC-labeled F-actin localization in SCRHs after treatment with DMSO (A), TA3 (5 μmol/L) (B), and TA3 (5 μmol/L)+NAC (5 mmol/L) (C) for 18 h. Pericanalicular F-actin was indicated by green fluorescence (20×magnification).

Discussion

BA homeostasis (including both synthesis and transporting processes) is strictly regulated in hepatocytes, which is critical to the maintenance of hepatocyte function. Interfering in these homeostatic mechanisms may lead to BA-induced hepatotoxicity22,23. Drug-induced cholestatic liver injury may be related to the direct inhibition of BA transporters (Ntcp and Bsep)2,24. Many laboratories have studied the mechanism of drug-induced cholestasis and have focused on the inhibition potency on BA transporters by a number of drugs, such as nefazodone25, ritonavir, and saquinavir15, all of which induce cholestasis and liver injury.

In the present study, inconsistent with the suggested safe use of Anemarrhena asphodeloides, we found that after a 14-day treatment of TA3 in rats, the levels of TBA and ALT in serum increased significantly (Figure 2A and Figure S2B). The analysis of the BA profile in bile (Figure 2B) suggested that the blockage of the excretion of BA could lead to the increase in BA in the blood and the disturbance of BA in the liver, which confirmed the preliminary observation that TA3 may produce cholestasis and potential liver injury.

The SCRH model was employed to interpret our in vivo observations. SCRHs are a valuable tool for evaluating metabolic enzyme- and hepatobiliary transporter-based hepatotoxicity26 because of their proper three-dimensional orientation and localization of important efflux transporters, such as Mrp2 and Bsep27,28. In SCRHs, BA could be taken into hepatocytes by Ntcp and Oatps and excreted into bile canaliculi by Bsep and Mrp2. After a 15 min treatment with TA3, there were no changes observed in the uptake and biliary excretion of d8-TCA (a stable isotope of BA). Given that Ntcp is responsible for the majority of BA uptake and this process is Na+-dependent, (Oatp transport of BA is Na+-independent)29, we compared the impact of Na+ on d8-TCA accumulation during TA3 treatment. It was found that TA3 had no effect on d8-TCA uptake in rat hepatocytes, regardless of the presence of Na+ (Figures 3A, 3B). These results indicated that TA3 was not a potent inhibitor of BA transporters. TA3 did not induce BA elevation by directly inhibiting BA uptake or efflux transporters.

However, if TA3 was incubated with hepatocytes for 2 or 24 h, the accumulation and biliary excretion of d8-TCA decreased significantly (Figures 3C, 3D, and Table 2). This suggested that TA3 time- and dose-dependently impaired the function of BA transporters in hepatocytes. It was reported that if xenobiotics interfere with BA transporters and enzyme expression, that normal BA homeostasis may be disturbed2. Therefore, we determined the impact of TA3 on the expression of BA-related genes Ntcp, Bsep, Mrp2, and Cyp7a1. A significant decrease in the expression of these genes was observed in SCRHs (Figures 4A–4D). The extent of the reduction of Ntcp was much greater than that of Bsep, suggesting that TA3 had a greater effect on BA uptake transporters than efflux transporters. This may lead to the decreased accumulation of BA. Mrp2 is responsible for mediating the excretion of divalent BAs and bilirubin22 and plays an important role in conjugated hyperbilirubinemia30. Mrp2 mRNA expression was also reduced by TA3, suggesting that it may contribute to TA3-induced cytotoxicity as well. The decrease in Cyp7a1 at both the gene and protein levels was considered to be negative feedback regulation following the reduction of BA accumulation in hepatocytes because CYP7a1 is the rate-limiting step in BA biosynthesis31.

Oxidative stress is often critical in drug-induced hepatotoxicity32,33,34. Our study revealed that TA3 treatment induced ROS generation in SCRHs and upregulated HO-1 gene expression, which is associated with the oxidative stress pathway (Figures 5A, 5B). The excess production of ROS can oxidize proteins, DNA, lipids, and other macromolecules, thereby leading to the disruption of cell processes and hepatocyte injury35,36. NAC reduced ROS production and restored ATP levels and MMP in TA3-treated hepatocytes (Figures 5C, 5D, and 5F). These results confirmed the role of oxidative stress in TA3-induced hepatotoxicity.

Mangiferin is one of the active compounds in Anemarrhena asphodeloides37,38, and the amount in the herb is greater than that of TA3. In our study, 10 μg/mL (approximately 25 μmol/L) mangiferin completely restored the TA3-induced ROS generation and the ATP and LDH changes to normal levels in hepatocytes (Figure 5E and Figure S3B). Not even NAC showed such an impressive protective effect on TA3-induced hepatotoxicity at this dose. This may be the key factor in explaining why no liver injury cases have been found after previous Anemarrhena asphodeloides treatment in the clinic.

Membrane transporters can be internalized by acute oxidative stress39,40, but there has been no direct connection reported between oxidative stress and liver transporter interruption in drug-induced cholestasis. It was previously reported that Ntcp could be internalized in the liver by taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDC); however, this process was not attributed to ROS41. For the same reason, it has been noted that oxidative stress may lead to cholestasis, but there was no connection between ROS and BA transporter expression42,43. In this study, the reduced expression levels of Ntcp, Bsep, and Mrp2 in SCRH were increased by NAC (Figure 6). The uptake and biliary excretion function of SCRH was also restored in the presence of NAC (Figure 7A–7D). These results implied that NAC or other antioxidants may increase the expression of BA transporters that have been reduced by drug-induced oxidative stress. This is the direct evidence in SCRHs that oxidative stress may lead to the disruption of polarized transporter systems in hepatocytes. By contrast, Cyp7a1 expression was still very low and could not be recovered by NAC, which implies that oxidative stress is not the only reason for TA3-induced cholestasis in the liver.

F-actin cytoskeletal integrity is required for the normal localization of transporters at the canalicular membrane domain44,45. It was reported that oxidative stress may induce the actin cytoskeleton and tight junction alterations in hepatocytes46. When the hepatocytes were treated with TA3, the pre-canalicular staining of F-actin became irregular and “fuzzy,” reflecting significant disruption. By contrast, the disruption of pre-canalicular F-actin was partly prevented in the TA3+NAC-treated cells (Figure 8). This could be another consequence of oxidative stress caused by the TA3 treatment.

In conclusion, our research explored the potential mechanisms of TA3-induced cholestasis and hepatotoxicity from a novel perspective: the connections between oxidative stress and liver transporter interruption. Using sandwich-cultured rat hepatocytes, our study revealed that TA3 does not inhibit BA transporters directly; however, TA3 may disrupt the polarization of the BA transporter system by generating ROS in hepatocytes. The antioxidants NAC and mangiferin effectively protected hepatocytes against TA3-induced cytotoxicity by attenuating oxidative stress. This study identified the connections between oxidative stress and liver transporter interruption in SCRHs.

Author contribution

Zhi-tao WU, Xin-ming QI, Cheng-gang HUANG, and Guo-yu PAN designed the research; Zhi-tao WU, Jing-jing SHENG, Lei-lei MA, and Xuan NI performed the experiments; Zhi-tao WU, Xin-ming QI, and Jin REN analyzed the data; Zhi-tao WU, Cheng-gang HUANG, and Guo-yu PAN wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 81302836, 81030065, and 81274055), the Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Major National Science and Technology Programs (Grant Nos 2012ZX09301001-006 and 2012ZX09302003), and the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (Grant No 2013AA032202).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Acta Pharmacologica Sinica's website.

Supplementary Material

Timosaponin A3 (TA3) induced liver injury in vivo.

Body weight (A) and serum biochemistry (ALT) (B) were measured after TA3 treatment for 14 days.

Protective effect of mangiferin (MGN) on TA3-induced hepatotoxicity.

References

- Hirschfield GM, Heathcote EJ, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis of cholestatic liver disease and therapeutic approaches. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1481–96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion TL, Leslie EM, Brouwer KL. Use of sandwich-cultured hepatocytes to evaluate impaired bile acid transport as a mechanism of drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:911–8. doi: 10.1021/mp0700357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler D, Konig J. Hepatic secretion of conjugated drugs and endogenous substances. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:265–72. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauner M, Boyer JL. Bile salt transporters: molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:633–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Jung K, Kim DH. Timosaponin AIII, a saponin isolated from Anemarrhena asphodeloides, ameliorates learning and memory deficits in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Chung HJ, Nam JW, Park HJ, Seo EK, Kim YS, et al. Cytotoxic and antineoplastic activity of timosaponin A-III for human colon cancer cells. J Nat Prod. 2011;74:701–6. doi: 10.1021/np1007735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Wu B, Fan M, Wang J, Huang J, Huang C. High-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry for metabolism study of timosaponin AIII. J Chromatogr Sci. 2014;52:418–22. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmt052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Dan Y, Yang D, Hu Y, Zhang L, Zhang C, et al. The genus Anemarrhena Bunge: A review on ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, He L, Yao D A J, Cao B, Ren J, et al. Alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate modulates hepatobiliary transporters in sandwich-cultured rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Lett. 2014;224:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, LeCluyse EL, Brouwer KR, Lightfoot RM, Lee JI, Brouwer KL. Use of Ca2+ modulation to evaluate biliary excretion in sandwich-cultured rat hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1592–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift B, Pfeifer ND, Brouwer KL. Sandwich-cultured hepatocytes: an in vitro model to evaluate hepatobiliary transporter-based drug interactions and hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Rev. 2010;42:446–71. doi: 10.3109/03602530903491881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Whiteman M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:231–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrebelski G, Nieminen AL, al-Ghoul K, Qian T, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. Progression of subcellular changes during chemical hypoxia to cultured rat hepatocytes: a laser scanning confocal microscopic study. Hepatology. 1995;21:1361–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata Y, Nagatsu T. Rotenone and CCCP inhibit tyrosine hydroxylation in rat striatal tissue slices. Toxicology. 2005;216:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae MP, Lowe CM, Tian X, Bourdet DL, Ho RH, Leake BF, et al. Ritonavir, saquinavir, and efavirenz, but not nevirapine, inhibit bile acid transport in human and rat hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1068–75. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.102657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Boiselle C, Wang J. Assessment of biliary clearance in early drug discovery using sandwich-cultured hepatocyte model. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1898–908. doi: 10.1002/jps.23070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie EM, Watkins PB, Kim RB, Brouwer KL. Differential inhibition of rat and human Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP/SLC10A1) by bosentan: a mechanism for species differences in hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:1170–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.119073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp DC, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Brouwer KL. Xenobiotics inhibit hepatic uptake and biliary excretion of taurocholate in rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2005;83:207–14. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K, Fukusaki E, Bamba T. Simultaneous and rapid analysis of bile acids including conjugates by supercritical fluid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1299:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Phillips MJ. Acute phalloidin toxicity in living hepatocytes. Evidence for a possible disturbance in membrane flow and for multiple functions for actin in the liver cell. Am J Pathol. 1986;122:101–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton JC, Matthews GM, Burgoyne RD, Mills CO, Chipman JK, Coleman R. Fluorescent choleretic and cholestatic bile salts take different paths across the hepatocyte: transcytosis of glycolithocholate leads to an extensive redistribution of annexin II. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:401–10. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padda MS, Sanchez M, Akhtar AJ, Boyer JL. Drug-induced cholestasis. Hepatology. 2011;53:1377–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.24229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson S, Stahl S, Paul N, Barber J, Kenna JG. In vitro inhibition of the bile salt export pump correlates with risk of cholestatic drug-induced liver injury in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:130–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattinger K, Funk C, Pantze M, Weber C, Reichen J, Stieger B, et al. The endothelin antagonist bosentan inhibits the canalicular bile salt export pump: a potential mechanism for hepatic adverse reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:223–31. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.114667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrubsky SE, Strom SC, Kalgutkar AS, Kulkarni S, Atherton J, Mireles R, et al. Inhibition of hepatobiliary transport as a predictive method for clinical hepatotoxicity of nefazodone. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:451–9. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyn T, Chatterjee S, Fattah S, Keemink J, Nicolai J, Augustijns P, et al. Sandwich-cultured hepatocytes: utility for in vitro exploration of hepatobiliary drug disposition and drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:589–616. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.773973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi YA, Kazolias D, Duignan DB. Use of cryopreserved human hepatocytes in sandwich culture to measure hepatobiliary transport. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1658–65. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.009118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier PJ, Stieger B. Bile salt transporters. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:635–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.082201.100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PA, Lan T, Rao A. Bile acid transporters. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2340–57. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900012-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler D. The roles of MRP2, MRP3, OATP1B1, and OATP1B3 in conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42:561–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.055772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JY. Regulation of bile acid synthesis: pathways, nuclear receptors, and mechanisms. J Hepatol. 2004;40:539–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JA, Roberts DW, James LP.Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver necrosisIn: Uetrecht J, editors. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Adverse drug reactions. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. p 369–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qi XM, Miao LL, Cai Y, Gong LK, Ren J. ROS generated by CYP450, especially CYP2E1,mediate mitochondrial dysfunction induced by tetrandrine in rat hepatocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:1229–36. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell DM, Gores GJ, Laskin DL, Hoofnagle JH. Drug-induced liver injury: mechanisms and test systems. Hepatology. 2001;33:1009–13. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Shinohara M, Ybanez MD, Saberi B, Kaplowitz N.Signal transduction pathways involved in drug-induced liver injuryIn: Uetrecht J, editors. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Adverse drug reactions. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. p 267–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li X, Cui X, Wang J, Yang J, Sun X, Li X, et al. Rhizome of Anemarrhena asphodeloides counteracts diabetic ophthalmopathy progression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1243–50. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Ichiki H, Iwamoto N, Kato M, Kubo M, Sasaki H, et al. Antidiabetic activity of the rhizoma of Anemarrhena asphodeloides and active components, mangiferin and its glucoside. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1009–11. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine S, Yano K, Saeki J, Hashimoto N, Fuwa T, Horie T. Oxidative stress is a triggering factor for LPS-induced Mrp2 internalization in the cryopreserved rat and human liver slices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine S, Ito K, Horie T. Oxidative stress and Mrp2 internalization. Free Radical Biol Med. 2006;40:2166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlfeld S, Domanova O, Berlage T, Stross C, Helmer A, Keitel V, et al. Short-term feedback regulation of bile salt uptake by bile salts in rodent liver. Hepatology. 2012;56:2387–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.25955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zhou G, Wang J, Jia L, Zhang P, Li R, et al. Paeoniflorin protects against ANIT-induced cholestasis by ameliorating oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;58:242–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding LL, Zhang BF, Dou W, Yang L, Zhan CS, Wang ZT. Protective effect of Danning tablet on acute livery injury with cholestasis induced by alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma MG, Milkiewicz P, Elias E, Coleman R. Control by signaling modulators of the sorting of canalicular transporters in rat hepatocyte couplets: role of the cytoskeleton. Hepatology. 2000;32:1342–56. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost D, Kartenbeck J, Keppler D. Changes in the localization of the rat canalicular conjugate export pump Mrp2 in phalloidin-induced cholestasis. Hepatology. 1999;29:814–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez LM, Milkiewicz P, Ahmed-Choudhury J, Elias E, Ochoa JE, Sanchez Pozzi EJ, et al. Oxidative stress induces actin-cytoskeletal and tight-junctional alterations in hepatocytes by a Ca2+-dependent, PKC-mediated mechanism: protective effect of PKA. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2005–17. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Timosaponin A3 (TA3) induced liver injury in vivo.

Body weight (A) and serum biochemistry (ALT) (B) were measured after TA3 treatment for 14 days.

Protective effect of mangiferin (MGN) on TA3-induced hepatotoxicity.