Background: Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) and the O subfamily of forkhead/winged helix transcription factors (FOXO) have pro-tumor or anti-tumor roles in human cancers.

Results: GSK3 up-regulates type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) expression and IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation through FOXO1/3/4.

Conclusion: GSK3 and FOXO promote hepatoma cell proliferation through IGF-IR.

Significance: These findings inform how GSK3 and FOXO promote cell proliferation.

Keywords: Cancer, FOXO, Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK-3), Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF), Receptor Tyrosine Kinase

Abstract

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) has either tumor-suppressive roles or pro-tumor roles in different types of human tumors. A number of GSK3 targets in diverse signaling pathways have been uncovered, such as tuberous sclerosis complex subunit 2 and β-catenin. The O subfamily of forkhead/winged helix transcription factors (FOXO) is known as tumor suppressors that induce apoptosis. In this study, we find that FOXO binds to type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) promoter and stimulates its transcription. GSK3 positively regulates the transactivation activity of FOXO and stimulates IGF-IR expression. Although kinase-dead GSK3β cannot up-regulate IGF-IR, the constitutively active GSK3β induces IGF-IR expression in a FOXO-dependent manner. Serum starvation or Akt inhibition leads to an increase in IGF-IR expression, which could be blunted by GSK3 inhibition. GSK3β knockdown or GSK3 inhibitor suppresses IGF-I-induced IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Moreover, knockdown of GSK3β or FOXO1/3/4 leads to a decrease in cellular proliferation and abrogates IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation. These results suggest that GSK3 and FOXO may positively regulate IGF-I signaling and hepatoma cell proliferation.

Introduction

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) was originally identified as a serine/threonine protein kinase that could phosphorylate and inactivate glycogen synthase, the final enzyme of glycogen biosynthesis (1). Besides glucose homeostasis, GSK3 plays important roles in a variety of cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, microtubule dynamics, cell cycle, and apoptosis (2). It is known that GSK3 has diverse roles in a variety of human diseases, including diabetes, inflammation, neurological disorders, and cancer (3). The mammalian GSK3 family consists of two members, namely GSK3α and GSK3β. In addition to regulating glycogen metabolism, GSK-3 has been implicated in the regulation of glucose transport. Activation of GSK3 leads to a decrease in glucose transporter 1 expression and glucose uptake (4). Whereas phosphorylation at tyrosine 216 in GSK3β or tyrosine 279 in GSK3α enhances the kinase activity of GSK3, phosphorylation of serine 9 in GSK3β or serine 21 in GSK3α significantly decreases its enzymatic activity (5). The best characterized upstream kinase that inactivates GSK3β through phosphorylation of its N terminus at Ser-9 is Akt/PKB (6). In addition, protein kinase A (PKA), PKC, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase, and p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (p70S6K) are known to phosphorylate Ser-9 of GSK3β in a context-dependent manner (7). p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) also inactivates GSK3β in the brain and thymocytes by direct phosphorylation at its C-terminal Ser-389 residue (8).

Since the discovery of GSK3, an increasing number of GSK3 targets in diverse signaling pathways have been uncovered, such as tuberous sclerosis complex subunit 2 (TSC2) and β-catenin (9). Phosphorylation by GSK3 may either positively or negatively regulates its downstream substrates. GSK3 has been found to regulate the proteolysis of an increasing number of proteins. For example, casein kinase I phosphorylation of β-catenin primes it for subsequent GSK3β phosphorylation at multiple sites at the N terminus, leading to the recognition by β-transducin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase and rapid degradation by the 26 S proteasome (10). Also, phosphorylation by GSK3 induces both activation and degradation of MafA, SRC-3, and BCL-3 (11–14).

Previous studies indicate that GSK3β is a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Both GSK3β inhibition and activation may drive tumor progression, depending on the cell type. Although GSK3β promotes tumorigenesis in some cancer types such as pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and leukemia, it inhibits tumor growth in breast cancer and skin cancer (15–19). The inactivation of GSK3β has been detected in some cancer types, such as skin, breast, lung cancer, and melanoma, but is absent in gastrointestinal cancer, hepatic cancer, and pancreatic cancer (20). The mechanisms underlying the pleiotrophic effects of GSK3β may be attributable to its central role in diverse signaling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways (21). Whereas GSK3 targets β-catenin, a key mediator in the Wnt pathway, for proteasomal degradation, thereby antagonizing Wnt signaling, it targets IκB, a repressor of NF-κB, for degradation, thereby promoting NF-κB activation.

Besides GSK3β, the O subfamily of Forkhead/winged helix transcription factors (FOXO) is another downstream substrate of Akt, a key signaling node in multiple signal transduction pathways, including insulin signaling, insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling, and epidermal growth factor signaling. FOXO proteins are phylogenetically conserved and regulate key physiological functions, including cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and survival (22). Similar to GSK3, phosphorylation of FOXO by Akt leads to inactivation of FOXO. FOXOs activate transcription of the cell cycle inhibitors p27Kip1 and p21Cip1/WAF1, although they repress transcription of the cell cycle activators cyclin D1 and cyclin D2 (23). FOXO also activates the cell cycle inhibitor cyclin G2 (24). Moreover, insulin and IGF-I have been reported to down-regulate the expression of cyclin G2 as part of their mitogenic effect (25). Hence, FOXOs are considered as tumor suppressors. However, signaling downstream of FOXO is both cell type-specific and tissue-specific. FOXOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors (26). Although many studies indicate that FOXOs are bona fide tumor suppressors, recent studies demonstrate that they have roles in promoting tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Depletion of FOXO3 reduced G1/S transition and cell proliferation in MCF7 breast cancer cells and H1299 lung cancer cells (27). Elevated FOXO3 expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia exhibiting normal cytogenetics, and genetic ablation of FOXO3 reduces disease burden in a murine model of chronic myeloid leukemia (28, 29). Another recent study has revealed that FOXO inhibition triggers myeloid cell maturation and acute myeloid leukemia cell death (30). FOXOs promote survival of hematopoietic cells after DNA damage (31). In addition, FOXOs up-regulate BCL-10 and activate NF-κB, thereby promoting survival of tumor cells under serum starvation (32). Interestingly, GSK3β positively regulates FOXO1 activity through direct binding to FOXO1 (33). Insulin and IGF signaling can induce Akt-mediated GSK3β and FOXO phosphorylation, resulting in the inactivation of GSK3β and FOXO.

Even though GSK3 is a well known downstream target of IGF-IR,2 it remains unclear whether GSK3β controls upstream elements governing IGF-IR signaling. Here, we report that GSK3 positively regulates IGF-IR expression. These effects are mediated, at least in part, by activation of FOXO transcription factors that directly bind to the IGF-IR promoter. Inhibition of GSK3 leads to a decrease in IGF-I-induced Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cellular proliferation. Together, these findings provide a mechanism whereby GSK3β enhances IGF-I signaling in hepatoma cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

LiCl was purchased from Sigma. IGF-I was purchased from PeproTech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ) and prepared by reconstituting in deionized water to the appropriate concentration and stored at −20 °C. The anti-IGF-IR, anti-FOXO1, anti-FOXO3, anti-FOXO4, anti-Akt, anti-ERK1/2, anti-HA, anti-phosphorylated IGF-IR (Tyr-1135), anti-phosphorylated Akt (Ser-473), and anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Another FOXO1 antibody for chromatin immunoprecipitation was from Abcam Ltd. (Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong). Anti-GSK3 antibody was purchased from Signalway Antibody LLc (Baltimore, MD). Anti-phosphorylated GSK3β (Ser-9) was purchased from Eptomics (Burlingame, CA). Anti-actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Culture

Hepatoma cancer cell lines HepG2 and SMMC-7721 were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing 10% newborn calf serum and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed every 2 days.

RNA Interference

The two target sequences for GSK3β knockdown are as follows: 1, GATCTGTCTTGAAGGAGAA; 2, ATAGTCCGATTGCGTTATT. The target sequences for FOXO1, FOXO3 and FOXO4 knockdown are GAGCGTGCCCTACTTCAAG, CAACCTGTCACTGCATAGT, and AGAAGCCGATATGTGGACC, respectively. The small interfering RNA (siRNA) against GSK3β and a negative control siRNA were provided by Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The siRNA against FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 are provided by GenePharma Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Proliferating cells in 6-well plates were incubated with 50 nm siRNA in 2 ml of OPTI-MEM® I reduced serum medium (Invitrogen) containing Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed with cold RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors for 30 min. 30 μg of protein was loaded into Tris-HCl-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in TBST, followed by incubating with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After rinsing the membrane in TBST three to four times, the membrane was incubated with appropriate HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was detected with chemifluorescent reagent.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First strand cDNAs were synthesized using the Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT) primers. GSK3β and IGF-IR were amplified by real time PCR using the SYBR® Select Master Mix (Invitrogen), and the total volume was 20 μl. β-Actin was also amplified as a reference gene. The primer sequences for human GSK3β were 5′-CTCCTCATGCTCGGATTCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCAGAAGCAGCATTATTGG-3′ (reverse). The primer sequences for human IGF-IR were 5′-AATCGCATCATCATAACCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATCCTGCCCATCATACTC-3′ (reverse). Relative quantification with the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) was done using the Ct method. The amount of GSK3β or IGF-IR gene normalized to the endogenous reference gene (β-actin) is given by 2− ΔCt, where ΔCt is Ct (GSK3β or IGF-IR) −Ct (β-actin).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (CHIP) Assay

ChIP assays were performed with the chromatin immunoprecipitation system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). Briefly, cells were fixed with formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After washing twice with 1× cold PBS containing proteinase inhibitor mixture II, the cells were scraped and lysed with cell lysis buffer and nuclear lysis buffer, and then the DNA was broken into pieces 200–1,000 bp in length by sonication. Soluble chromatin was co-immunoprecipitated with antibody against FOXO1 or IgG at 4 °C overnight. The de-cross-linked DNA samples were subjected to PCR.

Luciferase Assay

HepG2 or SMMC-7721 cells were seeded in six-well plates. After treatment with lithium chloride (LiCl) or transfection with siRNA or GSK3 plasmids, the cells were transfected with a total of 320 ng of FOXO-responsive luciferase construct (Addgene Inc., Cambridge, MA) per well mixed with the Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). Twenty four hours after transfection, the cells were harvested with 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega BioSciences, San Luis Obispo, CA). Luciferase activities were measured using the Promega luciferase assay kit.

Cell-lightTM EdU Assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5000 cells per well. Twenty four hours later, the cells were treated with or without LiCl (5 mm) or siRNA, followed by treating with or without 5 nm IGF-I. After 24 h, the cells were incubated with 50 μm EdU medium for 2 h. Next, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and incubated with 2 mg/ml glycine for 10 min. Following permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min, the cells were incubated in Apollo® 567 working solution for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with 1× Hoechst 33342 for 30 min at room temperature. After washing the cells with PBS three times, the cells were observed under fluorescence microscope.

RESULTS

GSK3 Up-regulates the Expression of IGF-IR

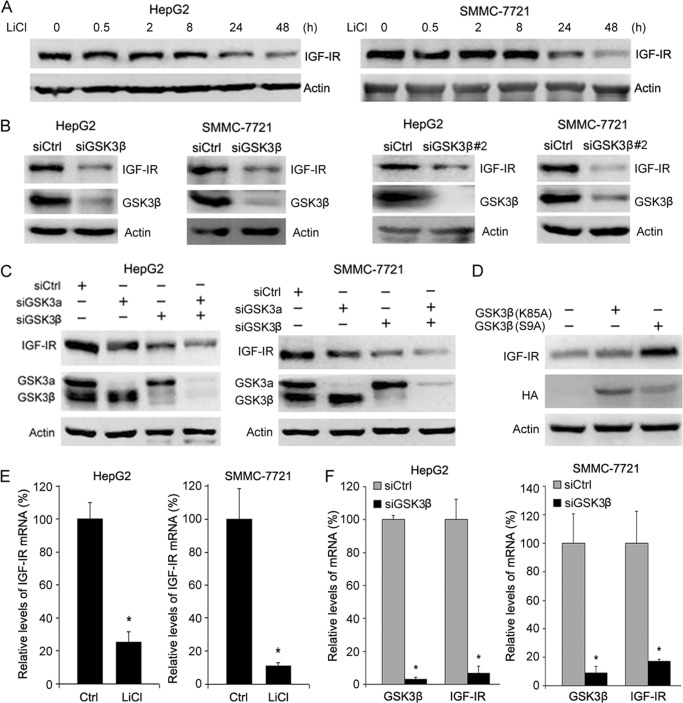

To determine whether GSK3 regulates IGF-IR expression, we treated hepatoma cells HepG2 with LiCl, a GSK3 inhibitor, and then detected IGF-IR levels by Western blotting. Treatment of HepG2 with LiCl led to a decrease in IGF-IR expression (Fig. 1A). Similar results were detected in another hepatoma cell line, SMMC-7721 (Fig. 1A). In addition, transfection of siRNA against GSK3β (siGSK3β) into both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells resulted in decreased IGF-IR levels (Fig. 1B). Similar results were detected in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells transfected with another siRNA against GSK3β (siGSK3β#2) (Fig. 1B). Moreover, GSK3α knockdown resulted in decreased IGF-IR expression to a much lesser extent than GSK3β depletion (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the next studies focus on GSK3β. Consistent with above-mentioned findings, overexpression of the constitutively active GSK3β (K85A) mutant in hepatoma cells led to an increase in IGF-IR expression, although overexpression of the kinase-dead GSK3β (S9A) mutant did not affect IGF-IR expression (Fig. 1D). To determine whether GSK3β regulates IGF-IR expression at the transcription level, we treated hepatoma cells with LiCl and then detected IGF-IR mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR. Treatment of hepatoma cells with LiCl led to a decrease in IGF-IR transcription (Fig. 1E). GSK3β knockdown also reduced IGF-IR transcription (Fig. 1F). Collectively, these data demonstrate that GSK3β positively regulates IGF-IR expression.

FIGURE 1.

GSK3 up-regulates IGF-IR expression. A, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without 10 mm LiCl for indicated periods, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR expression. B, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl, siGSK3β, or siGSK3β#2 for 48 h, followed by Western blot analysis of GSK3β and IGF-IR expression. C, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl, siGSK3α, or siGSK3β for 48 h, followed by Western blot analysis of GSK3 and IGF-IR expression. D, HepG2 cells were transfected with or without HA-tagged phosphomimetic GSK3β (K85A) or phosphodeficient GSK3β (S9A) mutants, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR and HA. E, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without 10 mm LiCl for 24 h, followed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of IGF-IR expression. The relative levels of IGF-IR transcription were plotted. The relative levels of IGF-IR transcription were plotted. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. F, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siGSK3β for 24 h, followed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of IGF-IR expression. The relative levels of IGF-IR transcription were plotted. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.001.

FOXO1/3/4 Mediate the Induction of IGF-IR Expression by GSK3β

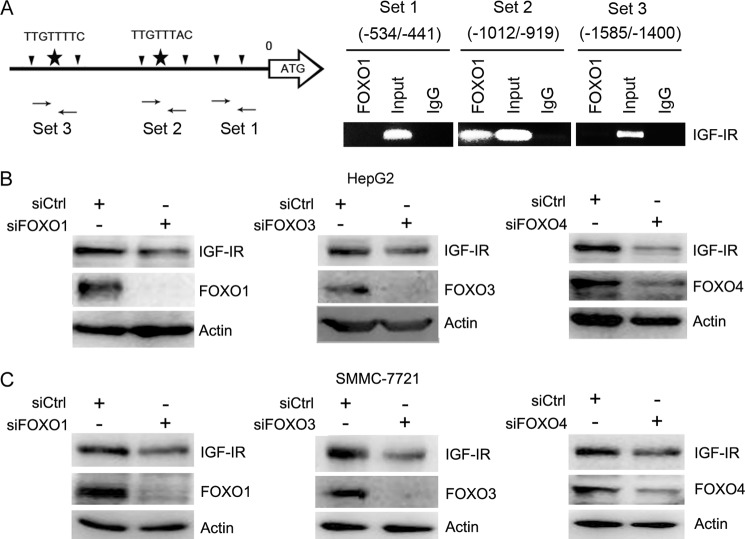

Although IGF-IR is overexpressed in a variety of tumor cells, little is known how IGF-IR expression is regulated. Bioinformatic analysis of the IGF-IR promoter indicates that there are two potential FOXO-binding sites (site 1, −1460TTGTTTTC−1453; site 2, −981TTGTTTAC−974) within the promoter of IGF-IR (34). Previous study also demonstrated that knockdown of FOXO, especially FOXO3, abrogated Akt inhibitor-induced IGF-IR expression in breast cancer cells (35). However, it remains unknown whether FOXO directly binds to IGF-IR promoter. To determine whether FOXO directly binds to these potential sites, we took advantage of CHIP analysis. We designed two pairs of primers to amplify DNA sequences spanning two potential FOXO-binding sites and one pair of primer to amplify an irrelevant sequence. The chromosome DNA immunoprecipitated by anti-FOXO1 antibody, and IgG was subjected to PCR with three pairs of primers indicated in Fig. 2A. The results demonstrated that FOXO1 binds to the site more close to the transcription start site (−981TTGTTTAC−973) (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

FOXO up-regulates IGF-IR expression. A, schematic illustration of potential FOXO-binding sites in IGF-IR promoter. The primers for CHIP analysis were also indicated. The chromatin immunoprecipitated with anti-FOXO1 antibody and IgG was subjected to PCR. B, HepG2 cells were transfected with siCtrl, siFOXO1, siFOXO3, or siFOXO4 for 48 h, followed by Western blot analysis of FOXO and IGF-IR expression. C, SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl, siFOXO1, siFOXO3, or siFOXO4 for 48 h, followed by Western blot analysis of FOXO and IGF-IR expression.

To determine whether FOXO regulates IGF-IR expression in hepatoma cells, we transfected HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells with siRNA to FOXO1, FOXO3, or FOXO4, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR expression. FOXO1, FOXO3, or FOXO4 knockdown led to a decrease in IGF-IR expression in both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 2, B and C). These data demonstrate that FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 activate IGF-IR expression.

To ensure that GSK3 regulates FOXO activity in hepatoma cells, we transfected FOXO-luc into HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells, followed by treatment with LiCl and detection of luciferase activity. LiCl significantly inhibited the transactivation activity of FOXO in both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, GSK3β knockdown resulted in a decrease in the transactivation activity of FOXO (Fig. 3B). A similar effect was detected in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells transfected with siGSK3β#2 (Fig. 3C). Consistent with above-mentioned findings, overexpression of HA-tagged constitutively active GSK3β in SMMC-7721 cells led to an increase in the transactivation activity of FOXO, although overexpression of HA-tagged kinase-dead GSK3β did not affect the transactivation activity of FOXO (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrate that GSK3β positivity regulate FOXO activity in hepatoma cells.

FIGURE 3.

GSK3 up-regulates IGF-IR expression through FOXO. A, FOXO-responsive luciferase construct was transiently transfected into HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells. Twenty four hours after transfection, cells were treated with or without LiCl for another 24 h, followed by detection of luciferase activities. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. B, detection of the effects of GSK3β knockdown on FOXO activities. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. In parallel, the efficacy of GSK3β knockdown was detected by Western blotting. C, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with another siRNA to GSK3β (siGSK3β#2), followed by detection of the effects of GSK3β knockdown on FOXO activities. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. In parallel, the efficacy of GSK3β knockdown was detected by Western blotting. D, SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with FOXO-responsive luciferase construct and kinase-dead or constitutively active GSK3β construct. Twenty four hours after transfection, the cells were subjected to detection of FOXO activity. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. E, SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with or without HA-tagged constitutively active GSK3β construct, and siCtrl or siFOXO1/3/4, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR, FOXO1/3/4, and HA tag.

To determine whether FOXO mediated the effect of GSK3β on IGF-IR expression, we transfected constitutively active GSK3β into SMMC-7721 cells, followed by transfection with siRNA to FOXO1/3/4 or control siRNA and Western blotting analysis of IGF-IR expression. Overexpression of active GSK3β increased IGF-IR expression. FOXO1/3/4 knockdown abrogated the induction of IGF-IR expression by active GSK3β (Fig. 3E). These data demonstrate that GSK3β stimulates IGF-IR expression through a FOXO-dependent mechanism.

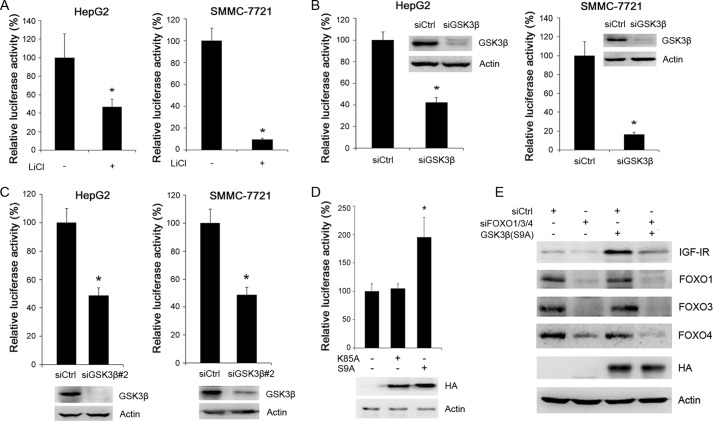

GSK3β and FOXO Mediate Serum Starvation-induced IGF-IR Expression

Because serum starvation could lead to the derepression of GSK3β, we detected the effects of serum starvation on IGF-IR expression. Upon serum starvation, a decrease in GSK3β phosphorylation and an increase in IGF-IR expression were detected in both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 4A). To determine whether serum starvation leads to changes in IGF-IR transcription, we detected levels of IGF-IR mRNA in serum-starved cells by real time RT-PCR. Serum starvation led to increased IGF-IR transcription in both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

GSK3 contributes to serum starvation-induced IGF-IR expression. A, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were cultured in medium containing 10% serum or 0.5% serum, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR expression and GSK3β phosphorylation. B, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were cultured in medium containing 10% serum or 0.5% serum, followed by real time RT-PCR analysis of IGF-IR and GSK3β transcription. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01. C, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were cultured in medium containing 10% serum or 0.5% serum and treated with or without 10 mm LiCl, followed by Western blot analysis of IGF-IR expression. D, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siGSK3β and cultured in medium containing 10% serum or 0.5% serum. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis of IGF-IR and GSK3β expression. E, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with FOXO-responsive luciferase construct and subjected to serum starvation in the absence or presence of 10 mm LiCl. Twenty four hours later, the luciferase activities were detected. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001. F, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with FOXO-responsive luciferase construct and siCtrl or siGSK3β, followed by serum starvation. Twenty four hours later, the luciferase activities were detected. Values represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001. In parallel, the efficacy of GSK3β knockdown was detected by Western blotting. G, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siFOXO1/3/4, followed by serum starvation. 48 h later, cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis of IGF-IR, FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 expression.

To determine whether GSK3β contributes to increased IGF-IR expression in response to serum starvation, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without LiCl, followed by serum starvation. Treatment of HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells with LiCl abrogated the induction of IGF-IR expression by serum starvation (Fig. 4C). GSK3β knockdown also abrogated the induction of IGF-IR expression by serum starvation (Fig. 4D).

Next, we detected the effect of serum starvation on the transactivation activity of FOXO. Serum starvation resulted in a significant increase in the transactivation activity of FOXO in both HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 4E). Treatment with LiCl inhibited the increase in the transactivation activity of FOXO (Fig. 4E). GSK3β knockdown also blunted the stimulation of FOXO activity by serum starvation (Fig. 4F). Moreover, FOXO1/3/4 knockdown abrogated the induction of IGF-IR expression by serum starvation (Fig. 4G). These data demonstrate that the GSK3β-FOXO axis contributes to the induction of IGF-IR expression by serum starvation.

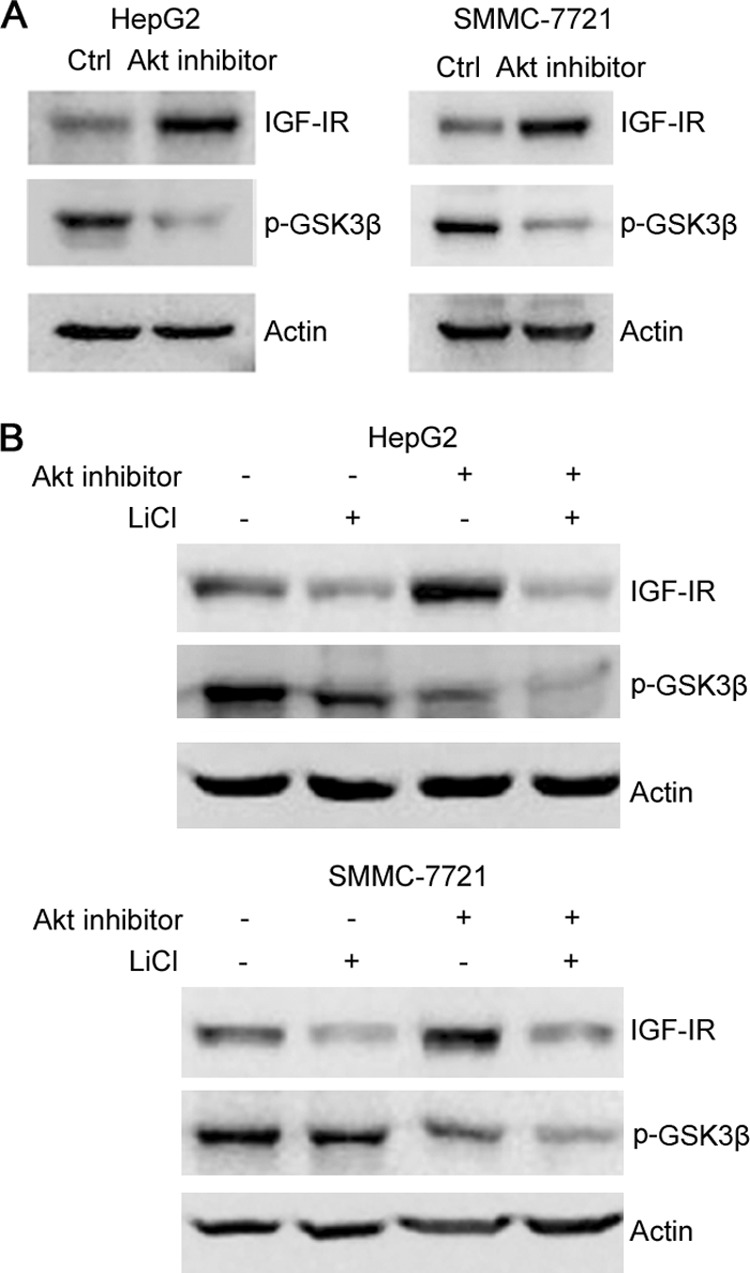

Akt can phosphorylate and inactivate both GSK3 and FOXO. We found that treatment of hepatoma cells with Akt inhibitor resulted in an increase in IGF-IR expression (Fig. 5A). Treatment of hepatoma cells with LiCl abrogated the increase in IGF-IR expression in response to Akt inhibition (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

GSK3 contributes to Akt inhibitor-induced IGF-IR expression. A, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without Akt inhibitor for 24 h, followed by Western blot analysis of GSK3β phosphorylation and IGF-IR expression. B, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without Akt inhibitor and LiCl for 24 h, followed by Western blot analysis of GSK3β phosphorylation and IGF-IR expression.

GSK3β Positively Regulates IGF-I Signaling

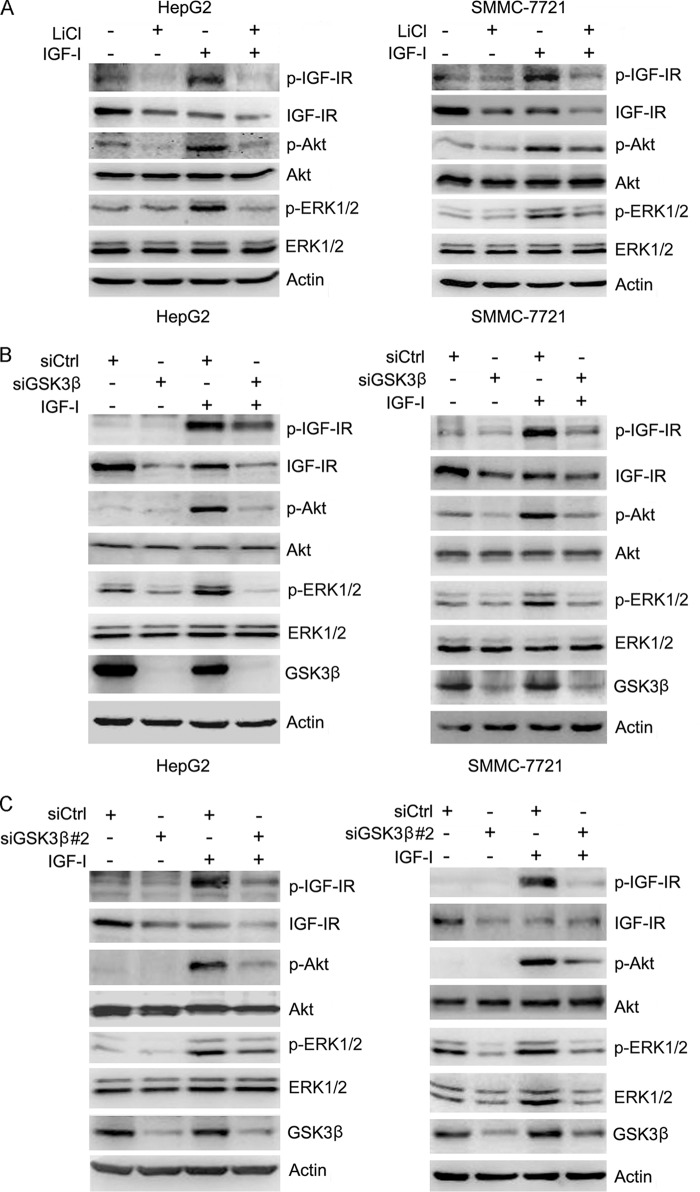

The above-mentioned data demonstrate that GSK3β positively regulates IGF-IR expression. To determine the effects of GSK3β on IGF-I-induced phosphorylation of IGF-IR and its downstream effectors, including ERK1/2 and Akt, HepG2 cells were pretreated with or without LiCl, followed by treating with or without IGF-I. Cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation of IGF-IR, ERK1/2, and Akt. The results demonstrated that LiCl inhibited IGF-IR expression and IGF-I-induced phosphorylation of IGF-IR, ERK1/2, and Akt (Fig. 6A). Similar results were detected in SMMC-7721 cells (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

GSK3β positively regulates IGF-I signaling. A, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were treated with or without 10 mm LiCl for 48 h, followed by treatment with or without IGF-I for 15 min. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis of IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The levels of total IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 were also detected. B, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siGSK3β-1 for 48 h, followed by treatment with or without IGF-I for 15 min. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis of IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The levels of total IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 were also detected. C, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siGSK3β-2 for 48 h, followed by treatment with or without IGF-I for 15 min. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis of IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The levels of total IGF-IR, Akt, and ERK1/2 were also detected.

In addition, HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with or without siRNA against GSK3β, followed by treating with or without IGF-I. Cell lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation of IGF-IR, ERK1/2, and Akt. GSK3β knockdown led to a decrease in IGF-I-induced phosphorylation of IGF-IR, ERK1/2, and Akt in both cell lines (Fig. 6B). Similar effects were detected in HepG2 and SMMC-7721 cells transfected with siGSK3β#2 (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that GSK3β positively regulates both IGF-IR expression and IGF-I signaling.

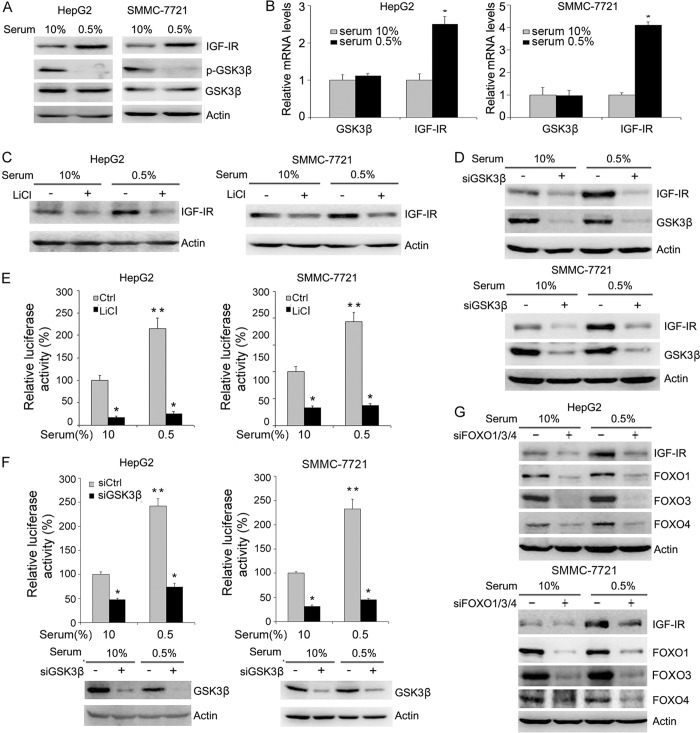

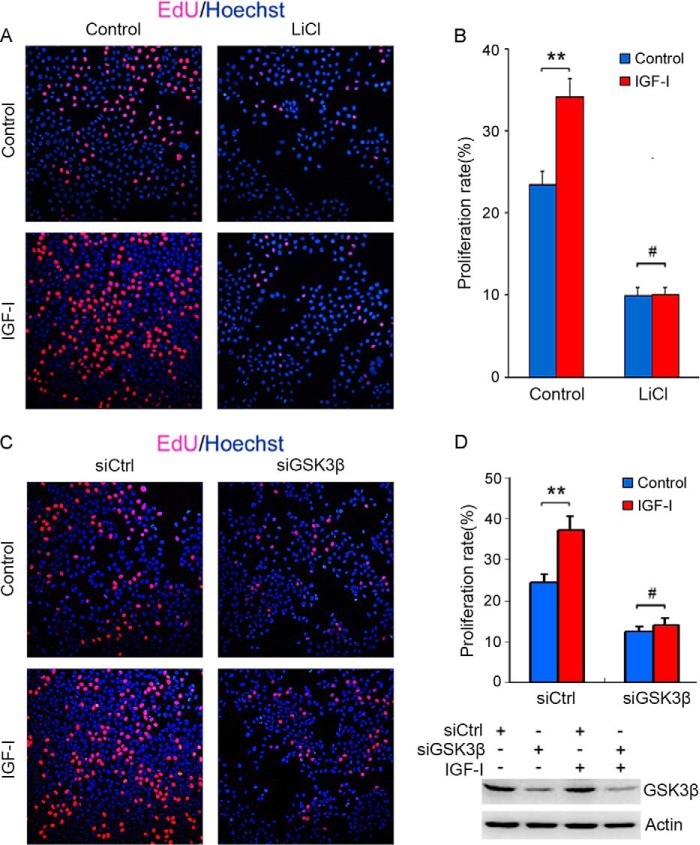

GSK3β and FOXO1/3/4 Positively Regulate IGF-I-induced Hepatoma Cell Proliferation

IGF-I is a mitogenic growth factor. To determine whether GSK3β regulates IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation, HepG2 cells were treated with or without LiCl and IGF-I, followed by detection of cellular proliferation by EdU labeling. Treatment with LiCl inhibited HepG2 cell proliferation and blunted IGF-I-induced cellular proliferation (Fig. 7, A and B). Similarly, GSK3β knockdown blunted IGF-I-induced cellular proliferation (Fig. 7, C and D).

FIGURE 7.

GSK3β positively regulates IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation. A, HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 3% serum and treated with or without IGF-I and 10 mm LiCl for 24 h, followed by labeling with EdU and Hoechst 33342. B, proliferating cells labeled by EdU were counted. The proliferation rate was plotted. Values represent means ± S.D. #, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01. C, HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 3% serum and transfected with siCtrl or siGSK3β. Twenty four hours later, the cells were treated with or without IGF-I for 24 h, followed by labeling with EdU and Hoechst 33342. D, proliferation rate was plotted. Values represent means ± S.D. #, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01. In parallel, the efficacy of GSK3β knockdown was detected by Western blotting.

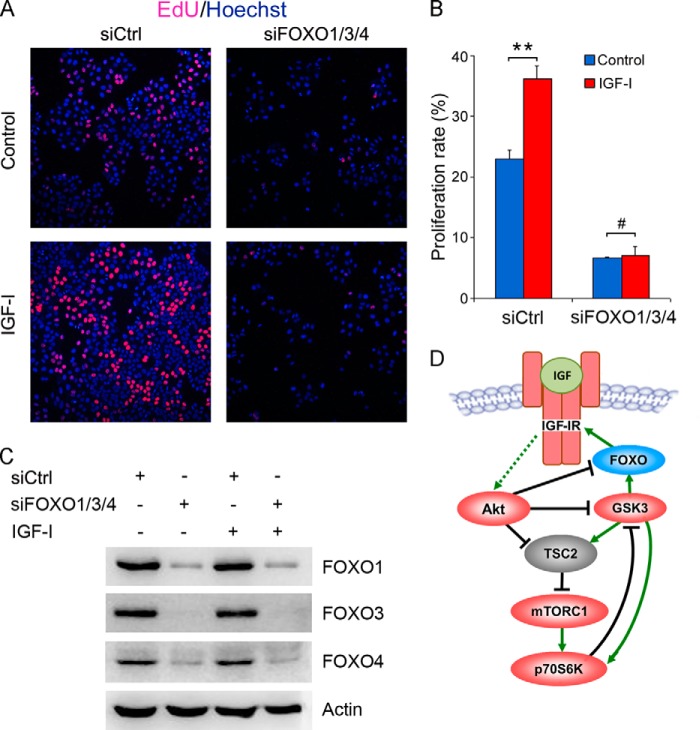

Next, we investigated the effects of FOXO knockdown on IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation. Although IGF-I significantly stimulated HepG2 cell proliferation, knockdown of FOXO1/3/4 inhibited HepG2 cell proliferation and blunted IGF-I-induced cellular proliferation (Fig. 8). These data indicate that FOXO1/3/4 promote IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation.

FIGURE 8.

FOXO1/3/4 knockdown blunts IGF-I-induced hepatoma cell proliferation. A, HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 3% serum and transfected with siCtrl or siFOXO1/3/4. Twenty four hours later, the cells were treated with or without IGF-I for 24 h, followed by labeling with EdU and Hoechst 33342. B, proliferation rate was plotted. Values represent means ± S.D. #, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01. C, in parallel, the efficacy of FOXO knockdown was detected by Western blotting. D, schematic illustration of feedback circuits in IGF-IR signaling.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies indicate that IGF-IR is required for the transforming ability of several oncogenes such as simian virus 40 large tumor antigen (36). In humans, IGF-IR and insulin receptor are widely expressed in normal tissues and frequently overexpressed in tumor cells (37, 38). Active Src has been shown to up-regulate IGF-IR expression in pancreatic cancer cells (39). Whereas Akt is identified as a downstream target of Src that positively regulates IGF-IR expression, hyperactive Akt reportedly down-regulates IGF-IR at the transcription level (40, 41). In both cases, the downstream effectors of Akt signaling that mediate the regulation of IGF-IR have not been identified. Among transcription factors, Sp1, cAMP-response element-binding protein, and mutant p53 have been shown to up-regulate IGF-IR expression, whereas wild-type p53 and the Wilms tumor suppressor gene WT1 negatively regulate IGF-IR expression (42–45). Mechanistically, mutant p53 interacts with the TATA box-binding protein to up-regulate IGF-IR expression at the level of transcription, whereas wild-type p53 represses IGF-IR expression (44). In addition, the IGF-I receptor gene promoter is a molecular target for the Ewing sarcoma-WT1 fusion protein (46). In this study, we demonstrate that FOXO directly regulates IGF-IR expression. Moreover, GSK3β promotes IGF-IR expression through stimulating FOXO activity.

Although IGF-IR is well known as a positive regulator of a wide range of cellular processes, ranging from cellular proliferation, migration, and survival, GSK3 is a multifunctional kinase regulating numerous signaling pathways such as NF-κB, mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin, either positively or negatively. GSK3β inhibits Wnt signaling by inducing β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation, leading to down-regulation of proto-oncogenes such as c-myc and cyclin D1. Hence, GSK3β is recognized as a tumor suppressor. Moreover, previous studies demonstrated that GSK3β could inhibit mTORC1 through TSC2 phosphorylation, which is a key mediator of growth factor signaling. The inhibition of mTOR signaling by GSK3β requires AMP-activated protein kinase activity (47). As shown in Fig. 8D, GSK3β directly activates p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K), a downstream target of mTORC1 (48). Reciprocally, p70S6K phosphorylates and then inactivates GSK3β, indicating a negative feedback loop. Upon growth factor stimulation, GSK3β may be inactivated by Akt thereby releasing its inhibitory effect on mTORC1, which then takes over GSK3β to activate p70S6K. Therefore, GSK3β and mTORC1 may positively regulate p70S6K under different conditions. In addition to a positive role for GSK3β in p70S6K activation, GSK3β stimulates NF-κB activity thereby promoting osteosarcoma cells survival (49). Our study highlights a positive role for GSK3β in IGF-IR expression and signaling. GSK3α has less effect than GSK3β on IGF-IR expression. Based on our data and previous investigations, the regulation of IGF-IR expression may involve multiple mechanisms. In resting cells, GSK3β and FOXO are active and positively regulate IGF-IR expression, poising IGF-IR at abundant levels ready to respond to IGF. Upon IGF stimulation, active Akt and S6K1 inhibit GSK3β and FOXO, allowing mTOR to be fully activated. The levels of IGF-IR, however, may decrease due to the inactivation of both GSK3 and FOXO. This is in fact the case called ligand-induced receptor down-regulation. It is known that ligand-induced IGF-IR activation is followed by proteasomal and lysosomal degradation of IGF-IR, a phenomenon of receptor desensitization (50). Thus, the net effects of GSK3β and FOXO on IGF-IR signaling would be positive, as demonstrated by our study.

Both GSK3 and FOXO proteins are best characterized Akt substrates. Like GSK3β, FOXOs are classically identified as tumor suppressors, because they promote cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by inducing p21, GADD45, p53, Fas ligand (FasL), Bim, bNIP3 and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (51). However, recent studies suggest that FOXOs may also paradoxically stimulate tumorigenesis (22, 23, 26–28). Sykes et al. (30) demonstrate a positive role for FOXOs in the maintenance of the immature state of leukemia-initiating cells by directly preventing their differentiation and apoptosis. Our study demonstrates that FOXO directly induces IGF-IR expression thereby enhancing IGF-I signaling. The involvement of FOXO in IGF-I-induced cell proliferation represents another mechanism underlying the positive regulation of tumorigenesis by FOXO. FOXO factors also have a role in controlling upstream signaling elements that govern insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. FOXO1 stimulates transcription of the insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2) in Drosophila and mammalian cells, and it thereby sensitizes the cellular response to insulin (52).

Akt's phosphorylation of both FOXO and GSK3 is inhibitory (6, 53). Therefore, under conditions in which Akt is inactive (e.g. growth factor withdrawal, serum starvation, and Akt inhibition), FOXO proteins and GSK3s are active. Consistent with the positive role of GSK3 and FOXO in IGF-IR expression, serum starvation or Akt inhibition results in increased IGF-IR expression, which can be blunted by GSK3 or FOXO inhibition. A key role of GSK3 would be boosting the abundance of IGF-IR to augment the responsiveness to its ligand when they are available. After IGF-IR is activated by its ligand, phosphorylation of Akt may in turn inactivate GSK3. Given that GSK3 may inhibit the downstream targets of Akt such as mTORC1, inactivation of GSK3 by Akt may allow the productive signal transduction. In this regard, GSK3β actually promotes the initiation of IGF-IR signaling.

The biological consequences of FOXO1/3/4 knockdown on hepatoma cell proliferation are very intriguing. FOXO1/3/4 depletion impairs hepatoma cell proliferation, which is in contrast to known roles of FOXO transcription factors in inducing cell cycle arrest through p27KIP1, p21, the Rb family member p130, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, cyclin G2, and GADD45 (23, 24). Notably, the regulation of the above-mentioned genes is context-dependent. In fact, the roles of FOXO transcription factors in cancer may be complex. Previous studies also demonstrate that FOXO contributes to Akt or mTOR inhibitor resistance in cancer cells through up-regulating receptor tyrosine kinases (54). In addition, a recent study reveals that FOXO3 directly binds to DNA replication factor Cdt1 and promotes cellular proliferation (27). This demonstrates that FOXO1/3/4 are positive regulators of hepatoma cell proliferation. Knockdown of FOXO1/3/4 blunts IGF-I-induced cellular proliferation. The regulation of IGF-IR expression may contribute, at least in part, to stimulation of hepatoma cell proliferation by FOXO. Collectively, these studies call for a revisit of FOXO transcription factors in cancer progression.

Footnotes

- IGF-IR

- type I insulin-like growth factor receptor

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cohen P., Frame S. (2001) The renaissance of GSK3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frame S., Cohen P. (2001) GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem. J. 359, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luo J. (2009) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 273, 194–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buller C. L., Loberg R. D., Fan M. H., Zhu Q., Park J. L., Vesely E., Inoki K., Guan K. L., Brosius F. C., 3rd (2008) A GSK-3/TSC2/mTOR pathway regulates glucose uptake and GLUT1 glucose transporter expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C836–C843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jope R. S., Yuskaitis C. J., Beurel E. (2007) Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem. Res. 32, 577–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. (1995) Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378, 785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frame S., Cohen P., Biondi R. M. (2001) A common phosphate binding site explains the unique substrate specificity of GSK3 and its inactivation by phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 7, 1321–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thornton T. M., Pedraza-Alva G., Deng B., Wood C. D., Aronshtam A., Clements J. L., Sabio G., Davis R. J., Matthews D. E., Doble B., Rincon M. (2008) Phosphorylation by p38 MAPK as an alternative pathway for GSK3β inactivation. Science 320, 667–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003) GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1175–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu C., Li Y., Semenov M., Han C., Baeg G. H., Tan Y., Zhang Z., Lin X., He X. (2002) Control of β-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 108, 837–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han S. I., Aramata S., Yasuda K., Kataoka K. (2007) MafA stability in pancreatic beta cells is regulated by glucose and is dependent on its constitutive phosphorylation at multiple sites by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6593–6605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rocques N., Abou Zeid N., Sii-Felice K., Lecoin L., Felder-Schmittbuhl M. P., Eychène A., Pouponnot C. (2007) GSK-3-mediated phosphorylation enhances Maf-transforming activity. Mol. Cell 28, 584–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu R. C., Feng Q., Lonard D. M., O'Malley B. W. (2007) SRC-3 coactivator functional lifetime is regulated by a phospho-dependent ubiquitin time clock. Cell 129, 1125–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Viatour P., Dejardin E., Warnier M., Lair F., Claudio E., Bureau F., Marine J. C., Merville M. P., Maurer U., Green D., Piette J., Siebenlist U., Bours V., Chariot A. (2004) GSK3-mediated BCL-3 phosphorylation modulates its degradation and its oncogenicity. Mol. Cell 16, 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ougolkov A. V., Fernandez-Zapico M. E., Savoy D. N., Urrutia R. A., Billadeau D. D. (2005) Glycogen synthase kinase-3β participates in nuclear factor κB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65, 2076–2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cao Q., Lu X., Feng Y. J. (2006) Glycogen synthase kinase-3β positively regulates the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Res. 16, 671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abrahamsson A. E., Geron I., Gotlib J., Dao K. H., Barroga C. F., Newton I. G., Giles F. J., Durocher J., Creusot R. S., Karimi M., Jones C., Zehnder J. L., Keating A., Negrin R. S., Weissman I. L., Jamieson C. H. (2009) Glycogen synthase kinase 3β missplicing contributes to leukemia stem cell generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3925–3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ding Q., He X., Xia W., Hsu J. M., Chen C. T., Li L. Y., Lee D. F., Yang J. Y., Xie X., Liu J. C., Hung M. C. (2007) Myeloid cell leukemia-1 inversely correlates with glycogen synthase kinase-3β activity and associates with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 4564–4571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farago M., Dominguez I., Landesman-Bollag E., Xu X., Rosner A., Cardiff R. D., Seldin D. C. (2005) Kinase-inactive glycogen synthase kinase 3β promotes Wnt signaling and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 65, 5792–5801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kang T., Wei Y., Honaker Y., Yamaguchi H., Appella E., Hung M. C., Piwnica-Worms H. (2008) GSK-3β targets Cdc25A for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and GSK-3β inactivation correlates with Cdc25A overproduction in human cancers. Cancer Cell 13, 36–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woodgett J. R. (2012) Can a two-faced kinase be exploited for osteosarcoma? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104, 722–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang H., Tindall D. J. (2007) Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2479–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kloet D. E., Burgering B. M. (2011) The PKB/FOXO switch in aging and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1926–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martínez-Gac L., Marqués M., García Z., Campanero M. R., Carrera A. C. (2004) Control of cyclin G2 mRNA expression by Forkhead transcription factors: Novel mechanism for cell cycle control by phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Forkhead. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2181–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Svendsen A. M., Winge S. B., Zimmermann M., Lindvig A. B., Warzecha C. B., Sajid W., Horne M. C., De Meyts P. (2014) Down-regulation of cyclin G2 by insulin, IGF-I (insulin-like growth factor 1) and X10 (AspB10 insulin): role in mitogenesis. Biochem. J. 457, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paik J. H., Kollipara R., Chu G., Ji H., Xiao Y., Ding Z., Miao L., Tothova Z., Horner J. W., Carrasco D. R., Jiang S., Gilliland D. G., Chin L., Wong W. H., Castrillon D. H., DePinho R. A. (2007) FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell 128, 309–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y., Xing Y., Zhang L., Mei Y., Yamamoto K., Mak T. W., You H. (2012) Regulation of cell cycle progression by forkhead transcription factor FOXO3 through its binding partner DNA replication factor Cdt1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5717–5722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Santamaría C. M., Chillón M. C., García-Sanz R., Pérez C., Caballero M. D., Ramos F., de Coca A. G., Alonso J. M., Giraldo P., Bernal T., Queizán J. A., Rodriguez J. N., Fernández-Abellán P., Bárez A., Peñarrubia M. J., Vidriales M. B., Balanzategui A., Sarasquete M. E., Alcoceba M., Díaz-Mediavilla J., San Miguel J. F., Gonzalez M. (2009) High FOXO3a expression is associated with a poorer prognosis in AML with normal cytogenetics. Leuk. Res. 33, 1706–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naka K., Hoshii T., Muraguchi T., Tadokoro Y., Ooshio T., Kondo Y., Nakao S., Motoyama N., Hirao A. (2010) TGF-β-FOXO signalling maintains leukaemia-initiating cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature 463, 676–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sykes S. M., Lane S. W., Bullinger L., Kalaitzidis D., Yusuf R., Saez B., Ferraro F., Mercier F., Singh H., Brumme K. M., Acharya S. S., Scholl C., Schöll C., Tothova Z., Attar E. C., Fröhling S., DePinho R. A., Armstrong S. A., Gilliland D. G., Scadden D. T. (2011) AKT/FOXO signaling enforces reversible differentiation blockade in myeloid leukemias. Cell 146, 697–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lei H., Quelle F. W. (2009) FOXO transcription factors enforce cell cycle checkpoints and promote survival of hematopoietic cells after DNA damage. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1294–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Z., Zhang H., Chen Y., Fan L., Fang J. (2012) Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protein activates nuclear factor κB through B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 10 (BCL10) protein and promotes tumor cell survival in serum deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17737–17745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sakamaki J., Daitoku H., Kaneko Y., Hagiwara A., Ueno K., Fukamizu A. (2012) GSK3β regulates gluconeogenic gene expression through HNF4α and FOXO1. J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 32, 96–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xuan Z., Zhang M. Q. (2005) From worm to human: bioinformatics approaches to identify FOXO target genes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 126, 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chandarlapaty S., Sawai A., Scaltriti M., Rodrik-Outmezguine V., Grbovic-Huezo O., Serra V., Majumder P. K., Baselga J., Rosen N. (2011) AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell 19, 58–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sell C., Rubini M., Rubin R., Liu J. P., Efstratiadis A., Baserga R. (1993) Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen is unable to transform mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11217–11221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hellawell G. O., Turner G. D., Davies D. R., Poulsom R., Brewster S. F., Macaulay V. M. (2002) Expression of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor is up-regulated in primary prostate cancer and commonly persists in metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 62, 2942–2950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Law J. H., Habibi G., Hu K., Masoudi H., Wang M. Y., Stratford A. L., Park E., Gee J. M., Finlay P., Jones H. E., Nicholson R. I., Carboni J., Gottardis M., Pollak M., Dunn S. E. (2008) Phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor-i/insulin receptor is present in all breast cancer subtypes and is related to poor survival. Cancer Res. 68, 10238–10246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flossmann-Kast B. B., Jehle P. M., Hoeflich A., Adler G., Lutz M. P. (1998) Src stimulates insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)-dependent cell proliferation by increasing IGF-I receptor number in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 58, 3551–3554 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanno S., Tanno S., Mitsuuchi Y., Altomare D. A., Xiao G. H., Testa J. R. (2001) AKT activation up-regulates insulin-like growth factor I receptor expression and promotes invasiveness of human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 61, 589–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qin L., Wang Y., Tao L., Wang Z. (2011) AKT down-regulates insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor as a negative feedback. J. Biochem. 150, 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Werner H., Hernández-Sánchez C., Karnieli E., Leroith D. (1995) The regulation of IGF-I receptor gene expression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 27, 987–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Genua M., Pandini G., Sisci D., Castoria G., Maggiolini M., Vigneri R., Belfiore A. (2009) Role of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein in insulin-like growth factor-i receptor up-regulation by sex steroids in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 7270–7277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Werner H., Karnieli E., Rauscher F. J., LeRoith D. (1996) Wild-type and mutant p53 differentially regulate transcription of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8318–8323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Werner H., Re G. G., Drummond I. A., Sukhatme V. P., Rauscher F. J., 3rd, Sens D. A., Garvin A. J., LeRoith D., Roberts C. T., Jr. (1993) Increased expression of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene, IGF1R, in Wilms tumor is correlated with modulation of IGF1R promoter activity by the WT1 Wilms tumor gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5828–5832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Karnieli E., Werner H., Rauscher F. J., 3rd, Benjamin L. E., LeRoith D. (1996) The IGF-I receptor gene promoter is a molecular target for the Ewing's sarcoma-Wilms' tumor 1 fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19304–19309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Inoki K., Ouyang H., Zhu T., Lindvall C., Wang Y., Zhang X., Yang Q., Bennett C., Harada Y., Stankunas K., Wang C. Y., He X., MacDougald O. A., You M., Williams B. O., Guan K. L. (2006) TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell 126, 955–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shin S., Wolgamott L., Yu Y., Blenis J., Yoon S. O. (2011) Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 promotes p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) activity and cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E1204–E1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tang Q. L., Xie X. B., Wang J., Chen Q., Han A. J., Zou C. Y., Yin J. Q., Liu D. W., Liang Y., Zhao Z. Q., Yong B. C., Zhang R. H., Feng Q. S., Deng W. G., Zhu X. F., Zhou B. P., Zeng Y. X., Shen J. N., Kang T. (2012) Glycogen synthase kinase-3β, NF-κB signaling, and tumorigenesis of human osteosarcoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104, 749–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vecchione A., Marchese A., Henry P., Rotin D., Morrione A. (2003) The Grb10/Nedd4 complex regulates ligand-induced ubiquitination and stability of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3363–3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fu Z., Tindall D. J. (2008) FOXOs, cancer and regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene 27, 2312–2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Puig O., Tjian R. (2005) Transcriptional feedback control of insulin receptor by dFOXO/FOXO1. Genes Dev. 19, 2435–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brunet A., Bonni A., Zigmond M. J., Lin M. Z., Juo P., Hu L. S., Anderson M. J., Arden K. C., Blenis J., Greenberg M. E. (1999) Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96, 857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Muranen T., Selfors L. M., Worster D. T., Iwanicki M. P., Song L., Morales F. C., Gao S., Mills G. B., Brugge J. S. (2012) Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR leads to adaptive resistance in matrix-attached cancer cells. Cancer Cell 21, 227–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]