Background: To understand the differential response to cannabinoids, we examined the functional selectivity of type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1) agonists in a cell model of striatal neurons.

Results: 2-Arachidonylglycerol, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and CP55,940 were arrestin2-selective; endocannabinoids and WIN55,212-2 activated Gαi/o, Gβγ, and Gαq; and cannabidiol activated Gαs independent of CB1.

Conclusion: Cannabinoids displayed functional selectivity.

Significance: CB1 functional selectivity may be exploited to maximize therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: Anandamide (N-Arachidonoylethanolamine) (AEA), Arrestin, Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET), Cannabinoid, Cannabinoid Receptor, Cell Signaling, Neurobiology, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 2-Arachidonylglycerol, Cannabidiol

Abstract

Modulation of type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1) activity has been touted as a potential means of treating addiction, anxiety, depression, and neurodegeneration. Different agonists of CB1 are known to evoke varied responses in vivo. Functional selectivity is the ligand-specific activation of certain signal transduction pathways at a receptor that can signal through multiple pathways. To understand cannabinoid-specific functional selectivity, different groups have examined the effect of individual cannabinoids on various signaling pathways in heterologous expression systems. In the current study, we compared the functional selectivity of six cannabinoids, including two endocannabinoids (2-arachidonyl glycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA)), two synthetic cannabinoids (WIN55,212-2 and CP55,940), and two phytocannabinoids (cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)) on arrestin2-, Gαi/o-, Gβγ-, Gαs-, and Gαq-mediated intracellular signaling in the mouse STHdhQ7/Q7 cell culture model of striatal medium spiny projection neurons that endogenously express CB1. In this system, 2-AG, THC, and CP55,940 were more potent mediators of arrestin2 recruitment than other cannabinoids tested. 2-AG, AEA, and WIN55,212-2, enhanced Gαi/o and Gβγ signaling, with 2-AG and AEA treatment leading to increased total CB1 levels. 2-AG, AEA, THC, and WIN55,212-2 also activated Gαq-dependent pathways. CP55,940 and CBD both signaled through Gαs. CP55,940, but not CBD, activated downstream Gαs pathways via CB1 targets. THC and CP55,940 promoted CB1 internalization and decreased CB1 protein levels over an 18-h period. These data demonstrate that individual cannabinoids display functional selectivity at CB1 leading to activation of distinct signaling pathways. To effectively match cannabinoids with therapeutic goals, these compounds must be screened for their signaling bias.

Introduction

Cannabinoids are a structurally diverse group of compounds that are broadly classified as endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids) (e.g. 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG)4 and anandamide (N-arachidonylethanolamine (AEA)), phytocannabinoids (e.g. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD)), and synthetic cannabinoids (e.g. WIN55,212-2 (WIN) and CP55,940 (CP)) (1).

Cannabinoids mediate their effects through several receptors, including the type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1), which has been studied intensively for its neuromodulatory activity. Many cannabinoids, including 2-AG, AEA, and THC, induce analgesic responses, and their use for chronic and acute pain conditions such as arthritis and migraine is being actively explored (2–4). Cannabinoids evoke hypolocomotive responses via CB1 and may be useful in the treatment of movement disorders such as tremor, ataxia, Tourette syndrome, Parkinson disease, and Huntington disease (5). CBD, acting independently of CB1, has been shown to have therapeutic potential as an anti-epileptic and anti-inflammatory agent (6–8). Modulation of CB1 activity in the central nervous system and periphery also affects appetite and glucose and fat metabolism (9). Cannabinoids may play a therapeutic role in the management of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and lipodystrophies (9). Additionally, it is important to understand how psychoactive cannabinoids, such as THC, affect neuronal activity via CB1 and other effectors within the context of substance abuse and addiction (1, 10–12).

Cannabinoids differ in their affinity for CB1 and their potency and efficacy of action via CB1 (1, 2, 13). The classical view of CB1 activation was that a correlation exists between binding affinity at CB1 and the potencies of cannabinoids to induce the in vivo tetrad responses of anti-nociception, hypoactivity, hypothermia, and catalepsy (2, 13–15). Because of this correlation, individual cannabinoids were expected to be similarly potent in all four tetrad responses (2). However, this is not the case for many cannabinoids. THC and WIN, for example, are more potent inducers of hypolocomotion than of catalepsy or hypothermia (16, 17). Similarly, AEA and THC differ in their potencies for anti-nociception and hypolocomotion in the ICR strain of mice (18) and their ability to evoke tolerance and dependence in fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) knock-out mice (19). Long et al. (20) and Schlosburg et al. (21) observed that selective blockade of AEA or 2-AG catabolism results in sustained analgesia or disruption of analgesia and cross-tolerance to other CB1 agonists, respectively. CBD, unlike other cannabinoids, does not evoke the tetrad responses (8). CBD demonstrates low affinity for CB1, and the in vivo effects of CBD, including its anti-inflammatory properties, appear to be CB1-independent (6–8, 12). Differences in the potency and efficacy of cannabinoids to evoke various responses in vivo may be exploited in the application of these compounds as therapies. Although these distinctions may result from pharmacokinetic differences, it is also possible that in vivo responses to cannabinoids may be mediated through the different effects of individual cannabinoids.

Distinct agonists appear to modulate the signaling specificity of CB1 through the coupling of different G proteins (2, 22). CB1 agonist-selective coupling to Gαi, Gαs, and Gαq has been demonstrated in cell lines overexpressing CB1 treated with WIN, CP, and other synthetic cannabinoids (23–25). The potency of AEA, CP, WIN, and other cannabinoids to stimulate [35S]GTPγS has been evaluated in rat cerebellar membranes (10) and N1E-115 cells overexpressing CB1 (14). In these and subsequent studies, WIN and CP were found to be full agonists of Gαi/o, whereas AEA and, to a lesser extent, THC were partial agonists (2, 13–15). It is thought that WIN and CP stabilize functionally different active conformations of CB1 resulting in a differential interaction and activation of G proteins (26, 27). In silico modeling of CB1-cannabinoid interactions suggests that each cannabinoid interacts with a different subset of residues on the third and fourth transmembrane helices of CB1 (28–30). Based on these data, Varga et al. (29) proposed that ligand-specific changes in CB1 conformation may enhance the binding of different G proteins (e.g. Gαi/o versus Gαs) or arrestins, which would in turn facilitate the activation of different signaling pathways downstream of CB1. Glass and Northup (22) used Sf9 cell membrane preparations containing CB1 and various G proteins to differentiate the Gαi- and Gαo-mediated effects of CB1. In their study, the synthetic cannabinoid HU210, WIN, and AEA were full agonists of Gαi, whereas THC acted as a partial agonist, and WIN, AEA, and THC were all partial agonists of Gαo relative to HU210 (22). Similar to Varga et al. (29), Glass and Northup (22) concluded that distinct agonists induce unique receptor conformations resulting in ligand-specific CB1-dependent G protein signaling. The data presented in their studies suggest that the pharmacological activity of cannabinoids acting through G proteins depends on their affinity for CB1 as well as the signaling bias of specific cannabinoids.

Beyond G proteins, the recruitment of arrestin1 and -2 to CB1 has also been examined (31–33). These studies report that CB1 interacts weakly with arrestin2, which facilitates internalization upon stimulation with WIN or CP in HEK cells, AtT20 immortalized mouse anterior pituitary cells, and U2OS human osteosarcoma cells stably expressing CB1 (31–33). WIN and CP have been shown to be differentially efficacious activators of tyrosine hydroxylase transcription, ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and JNK activation in neuroblastoma cells (14, 34, 35). Although these observations were not related to agonist-specific coupling, the authors (14, 34, 35) suggest that the differences between WIN and CP support functional selectivity of cannabinoids at CB1. Other cannabinoids, such as CBD, have been shown to have some CB1 modulatory activity but act largely via CB1-independent effectors (6–8). To complicate matters, the functional selectivity of cannabinoid ligands may be cell type-specific because reports of efficacy have varied across model systems and tissues (2). Therefore, individual cannabinoids may stabilize specific CB1 receptor conformations, resulting in a cell- and tissue-specific response (32, 33). This is interesting because it may be possible for cannabinoids to be designed that bias receptor signaling toward desirable effects and away from undesirable ones.

In this study, we sought to characterize the ligand bias of several cannabinoid ligands in an in vitro model of neurons that express CB1. To directly compare cannabinoid ligand bias, the downstream functional selectivity of two compounds from three classes of cannabinoids was examined in the STHdhQ7/Q7 cell culture model of striatal medium spiny projection neurons. This cell culture model was chosen to characterize cannabinoid ligand bias because these cells model the major output of the indirect motor pathway of the striatum where CB1 levels are highest relative to other regions of the brain (36, 37). STHdhQ7/Q7 cells endogenously express CB1 and FAAH (36, 37), as well as the dopamine D2 receptor enkephalin and other markers of striatal neurons, making this in vitro model system ideally suited to studying cannabinoid signaling in a physiologically relevant context. The endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG, the phytocannabinoids CBD and THC, and the synthetic cannabinoids WIN and CP were compared for their ability to activate arrestin2 (β-arrestin1)-, Gαi/o-, Gαs-, and Gαq-dependent pathways in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells. Based on the existing in vitro and in vivo data for cannabinoid ligands, we hypothesized that endocannabinoids, phytocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids would differentially bias CB1-dependent signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cannabinoids used in this study included 2-AG, AEA, WIN, CP, CBD, THC, and the CB1-selective antagonist O-2050. All cannabinoids were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, United Kingdom) with the exception of THC, which was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON). Pertussis and cholera toxins (PTx and CTx) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The Gβγ modulator gallein was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Cannabinoids and gallein were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (final concentration of 0.1% in assay media for all assays) and added directly to the media at the concentrations and times indicated. No effects of vehicle alone were observed compared with assay media alone. PTx and CTx were dissolved in dH2O (50 ng/ml) and added directly to the media 24 h prior to cannabinoid treatment. Pretreatment of cells with PTx and CTx inhibits Gαi/o and Gαs, respectively (38). In the case of CTx, this occurs via down-regulation of Gαs following ADP-ribosylation (38, 39). All experiments included a vehicle treatment control.

STHdhQ7/Q7 cells are a cell line derived from the conditionally immortalized striatal progenitor cells of embryonic day 14 C57BlJ/6 mice (Coriell Institute, Camden, NJ) (36). Cells were grown at 33 °C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 104 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 400 μg/ml Geneticin. Twenty-four hours of serum deprivation promotes the differentiation of STHdhQ7/Q7 cells into an adult neuron-like phenotype characterized by increased neurite outgrowth, GABA release, and increased expression of CB1, dopamine D2 receptors, preproenkephalin, and dopamine and cAMP-related phosphoprotein 32 kDa (DARPP-32), typical of mature medium spiny projection neurons of the indirect motor pathway of the striatum (36, 37, 40). These cells are ideally suited for the characterization of cannabinoid ligand bias in vitro because they model a neuronal cell type that expresses CB1 at high levels compared with other cell types in the central nervous system. The striatum is a major site of action of centrally acting cannabinoid-based therapies (41, 42).

Plasmids

Human CB1 and arrestin2 (β-arrestin1) were cloned and expressed as either green fluorescent protein2 (GFP2) or Renilla luciferase (Rluc) fusion proteins at the intracellular C terminus. CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-GFP2 were generated using the pGFP2-N3 plasmid (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) as described previously (43). CB1-Rluc and arrestin2-Rluc were generated using the pRluc-N3 plasmid (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The human ether-a-go-go-related gene-C terminus GFP2 and Rluc fusion constructs (HERG-GFP2 and HERG-Rluc), GFP2-Rluc fusion construct, and Rluc plasmids have been described previously (40, 44, 45). The Gαq dominant negative mutant (Glu-209ΔLeu,Asp-277ΔAsn (Q209L,D277N)) pcDNA3.1 plasmid was obtained from the Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO) (25). The arrestin2 dominant negative mutant (Val-53ΔAsp (V53D)) pcDNA3.1 plasmid has been described previously (45). The arrestin2-red fluorescent protein (RFP) was provided by Dr. Denis Dupré (Dalhousie University).

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer 2 (BRET2)

Direct interactions between CB1 and arrestin2 were quantified via BRET2 (46). Cells were grown in a 6-well plate and transfected with the indicated GFP2 and Rluc constructs. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, the cells were washed twice with cold 0.1 m PBS and suspended in 90 μl of 0.1 m PBS supplemented with glucose (1 mg/ml), benzamidine (10 mg/ml), leupeptin (5 mg/ml), and a trypsin inhibitor (5 mg/ml). Cells were dispensed into white 96-well plates and treated as indicated (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Coelenterazine 400a substrate (50 μm; Biotium, Hayward, CA) was added, and light emissions were measured at 405 nm (Rluc) and 510 nm (GFP2) using a Luminoskan Ascent plate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with an integration time of 10 s and a photomultiplier tube voltage of 1200 V. BRET efficiency (BRETeff) was determined using previously described methods (47) such that Rluc alone was used to calculate BRETmin and the Rluc-GFP2 fusion protein was used to calculate BRETmax.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

Receptor dimerization was visually assessed via FRET according to the methods of Wu et al. (48). Cells were grown in a 6-well plate and transfected with the indicated GFP2 and RFP constructs. Forty-eight hours post-transfection cells were moved to coverslips and grown for an additional 24 h. Cells were treated as indicated and visualized on a Zeiss 510 upright laser scanning microscope with 20× and 63× objective lenses. Images were captured using Zen Image Capture 2009 edition (Carl Zeiss Canada). The following excitation/emission filters were used to directly visualize fluorescence: for GFP2, 492 nm/510 nm; and for RFP, 543 nm/565 nm. For FRET, GFP2 was excited 488 nm, separated by a 488/564 dichromic mirror, with emitted fluorescence detected between 502 and 651 nm (48). To measure the endogenous association between CB1 and arrestin, paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were used for the immunocytochemical detection of CB1 with a C-terminal CB1 primary antibody (1:500; catalog No. 10006590, Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI) and Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (donor) and detection of arrestin2 with an arrestin1/2 primary antibody (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Cy3 secondary antibody (acceptor), as described by Knowles et al. (49). Cells were grown on coverslips and treated as indicated. Cells were washed with 0.1 m PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Cells were incubated with blocking solution (0.1 m PBS and 5% normal goat serum in dH2O) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated with primary antibody solutions directed against C-CB1 (1:500) and arrestin1/2 (1:250) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (0.1 M PBS, 1% (w/v) BSA, in dH2O) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Cells were incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500) and Cy3 (1:500) (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Microscopy and FRET were then conducted using the same methodology described for FRET in transfected cells. The specificity of the C-terminal CB1 and arrestin1/2 primary antibodies was confirmed using blocking peptide controls (1:500) (Cayman Chemical Co. and Santa Cruz Biotechnology). FRET efficiency was calculated in ImageJ by dividing the average pixel intensity at 565 nm for any given image by the intensity at 522 nm for that image after background subtraction. FRET was represented visually by mapping a pseudo-color lookup table (16 colors, ImageJ) onto the resulting image (48).

In- and On-cellTM Western Analyses and Immunocytochemistry

For On-cellTM Western analyses, cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde and washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Cells were incubated with blocking solution (0.1 m PBS and 5% normal goat serum in dH2O) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated with primary antibody solutions directed against N-CB1 (1:500; catalog No. 101500, Cayman Chemical Co.) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (0.1 M PBS and 1% (w/v) BSA in dH2O) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Cells were incubated in IR CW800 dye (1:500; Rockland Immunochemicals) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times with 0.1 m PBS for 5 min each. Cells were allowed to air-dry overnight. On-cellTM data were then collected using the Odyssey imaging system and software (version 3.0; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). These data represent the fraction of CB1 detected on the plasma membrane. The same cells were then used to quantify total CB1 protein levels using the In-cellTM Western technique. The On-cellTM CB1 levels were divided by the In-cellTM (total) CB1 levels to determine the fraction plasma membrane CB1. In-cellTM Western analyses and immunocytochemistry were conducted as described above except that 0.3% Triton X-100 was added to the blocking and antibody dilution solutions. Primary antibody solutions were: N-CB1 (1:500), pERK1/2 (Tyr-205/Tyr-185) (1:200), ERK1/2 (1:200), pCREB (Ser-133) (1:500), CREB (1:500), pPLCβ3 (Ser-537) (1:500), PLCβ3 (1:1000), pAkt (Ser-473) (1:500), panAkt (1:1000), arrestin1/2 (1:250), and β-actin (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). pERK1/2 (Tyr-205/Tyr-185), pAkt (Ser-473), pCREB (Ser-133), and pPLCβ3 (Ser-537) were chosen because phosphorylation at these sites demonstrates activation of the ERK, PI3K/Akt, CREB, and Gαq pathways, respectively. Secondary antibody solutions were IRCW700 and IRCW800 dyes (1:500; Rockland Immunochemicals). In-cellTM Western analyses were then conducted using the Odyssey imaging system and software (version 3.0; Li-Cor). All experiments measuring CB1 included an N-CB1 blocking peptide (1:500) control, which was incubated with N-CB1 antibody (1:500). Immunofluorescence observed with the N-CB1 blocking peptide was subtracted from all experimental replicates.

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR

RNA was harvested from cells using the TRIzol® (Invitrogen) extraction method according to the manufacturer's instruction. Reverse transcription reactions were carried out with SuperScript III® reverse transcriptase (+RT; Invitrogen) or without (−RT) as a negative control in subsequent PCR experiments according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of RNA was used per RT reaction. qRT-PCR was conducted using the LightCycler® system and software (version 3.0; Roche Applied Science). Reactions were composed of a primer-specific concentration of MgCl2 (Table 1), forward and reverse primers at 0.5 μm each (Table 1), 2 μl of LightCycler® FastStart SYBR Green I reaction mix, and 1 μl of cDNA to a final volume of 20 μl with dH2O (Roche Applied Science). The PCR program was as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, 50 cycles of 95 °C 10 s, a primer-specific annealing temperature (Table 1) for 5 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. Experiments always included sample-matched −RT controls, a no-sample dH2O control, and a standard control containing product-specific cDNA of a known concentration. cDNA abundance was calculated by comparing the cycle number at which a sample entered the logarithmic phase of amplification (crossing point) with a standard curve generated by amplification of cDNA samples of known concentration (LightCycler software, version 4.1; Roche Applied Science). qRT-PCR data were normalized to the expression of β-actin (50).

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Target | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Annealing temperature | MgCl2 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | mm | |||

| CB1 | GGGCAAATTTCCTTGTAGCA | 58 | 1 | Ref. 39 |

| GGCTAACGTGACTGAGAAA | ||||

| ppENK | GCGCGTTCTTCTCTCCTACA | 57 | 3 | This study |

| GTGCACGCCAGGAAATTGAT | ||||

| β-Actin | AAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAGAT | 59 | 2 | Ref. 39 |

| GTGGTACGACCAGAGGCATAC | ||||

| Arrestin2 | CACGCAGCCCTCACTCTC | 59 | 2 | This study |

| GTGTCACGTAGACTCGCCTT | ||||

| Arrestin3 | AAGGTGAAGCTGGTGGTGTC | 59 | 2 | This study |

| CCAGTGTGTATCTCGGGTGG |

Statistical Analyses

These were conducted by one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as indicated, using GraphPad (version 5.0, Prism). Post-hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni's or Tukey's test as indicated. Homogeneity of variance was confirmed using Bartlett's test. The level of significance was set to p < 0.001, < 0.01, or < 0.05, as indicated, and all results are reported as the mean ± S.E. from at least four independent experiments. To improve the readability of the data, many of the figures are subdivided as endocannabinoids (AEA and 2-AG), phytocannabinoids (CBD and THC), and synthetic cannabinoids (CP and WIN).

RESULTS

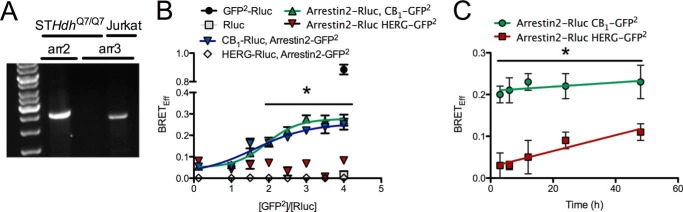

Interactions between CB1 and Arrestin2 (β-arrestin1) Are Ligand-specific

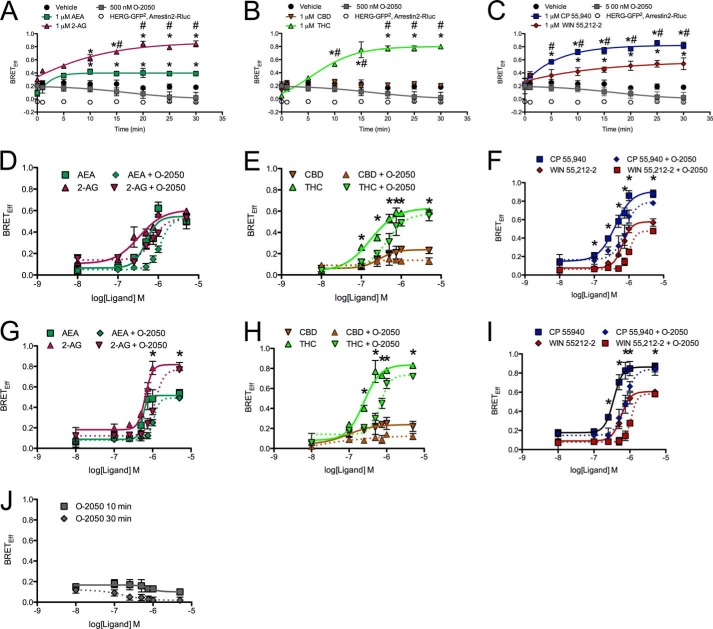

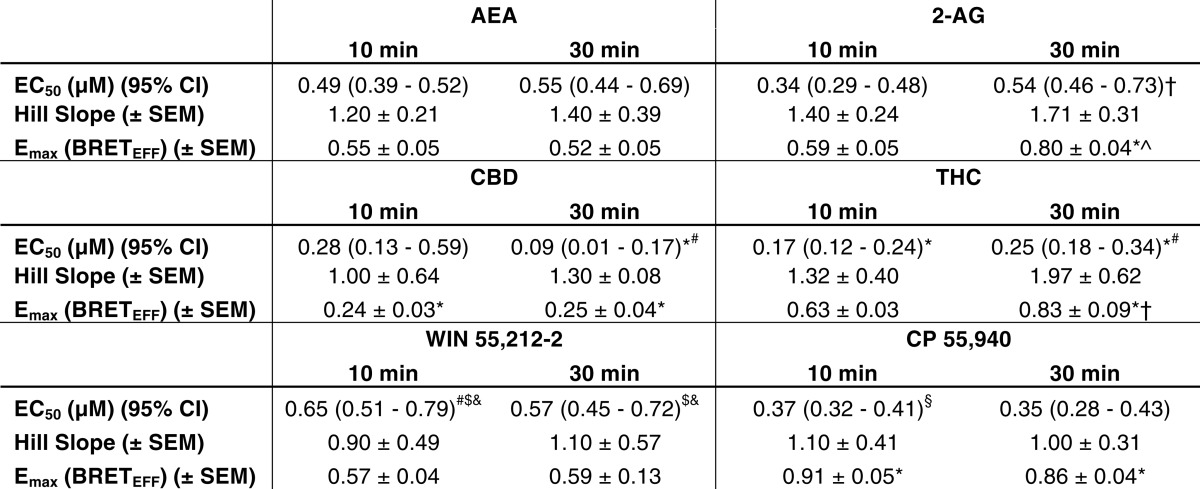

Initially we wanted to determine whether the interaction between CB1 and arrestin2 differed among CB1 agonists. To do this, BRETeff was measured between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc. Arrestin2 was chosen because it is endogenously expressed by STHdhQ7/Q7 cells (Fig. 1A). The amount of donor and acceptor plasmid used and the ratio of donor to acceptor plasmids were optimized using a BRET saturation curve at 400 ng of CB1-GFP2 to 200 ng of arrestin2-Rluc (2:1; Fig. 1B). Basal BRETeff between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc was ∼0.2 and greater than BRETeff between HERG-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc (Fig. 1B). We also verified that BRETeff was independent of time and plasmid expression level for CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc (Fig. 1C). Cells were treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, CP, or WIN or with 500 nm O-2050, for 0–30 min (Fig. 2, A–C). Treatment with AEA, 2-AG, THC, CP, or WIN increased BRETeff within 10 min compared with vehicle treatment, and BRETeff was stable over 30 min (Fig. 2, A–C). CBD and O-2050 treatment did not change BRETeff relative to vehicle treatment. In addition, BRETeff between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc was greater in cells treated with 2-AG compared with AEA by 15 min, with THC compared with CBD by 10 min, and with CP compared with WIN by 5 min (Fig. 2, A–C). The ligand-specific differences in CB1-arrestin2 association were further analyzed by measuring BRETeff in cells treated with 0.01–5.00 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, CP, or WIN in the absence or presence of 500 nm O-2050 for 10 (Fig. 2, D–F) or 30 min (Fig. 2, G–I). At 10 min, BRETeff between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc was not different in AEA- and 2-AG-treated cells (Fig. 2D), whereas THC and CP were more potent and efficacious ligands than CBD and WIN, respectively (Fig. 2, E and F). At 30 min, 2-AG was a more efficacious ligand than AEA (Fig. 2G). As observed at 10 min, THC and CP were more potent and efficacious ligands than CBD and WIN, respectively (Fig. 2, H and I). AEA-, 2-AG, THC-, WIN-, and CP-mediated recruitment of arrestin2 to CB1 was inhibited by co-treatment of cells with the CB1 antagonist O-2050, as demonstrated by a significant rightward shift in the BRETeff dose-response curves (Fig. 2, D–I). The EC50, Hill slope, and Emax values generated from these dose-response relationships were also compared (Table 2). THC was more potent than AEA and WIN at 10 min and more potent than AEA, 2-AG, and WIN at 30 min (Table 2). The flat dose-response relationship observed with CBD demonstrates that this ligand had very little effect on the interaction between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc because the basal BRETeff is not significantly different from the Emax (Fig. 2, E and H). 2-AG (30 min), THC (30 min), and CP (10 and 30 min) were more efficacious ligands and CBD (10 and 30 min) less efficacious than AEA for BRETeff between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc (Table 2). The BRETeff Emax values were greater at 30 min than at 10 min when cells were treated with 2-AG or THC (Table 2). No statistically significant changes in the Hill slope were observed. Based on these data, we concluded that 1) with the exception of CBD, each ligand promoted interactions between CB1 and arrestin2; 2) 2-AG, THC, and CP displayed higher maxima than the other cannabinoid ligands tested for enhancing CB1-arrestin2 interactions; and 3) in the assay, THC and CP were more potent than the other cannabinoid ligands tested for enhancing CB1-arrestin2 interactions. A final concentration of 1 μm was used for all subsequent experiments because this dose consistently produced a response that approximated the Emax observed for BRETeff for all cannabinoids tested.

FIGURE 1.

Optimization of BRET2 between arrestin2 (β-arrestin1) and CB1 in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells. A, representative image demonstrating that arrestin2, and not arrestin3, is expressed in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells. PCR products were amplified via qRT-PCR and resolved on agarose gels. B, cells were transfected with varying amounts of donor (CB1-Rluc, HERG-Rluc, and arrestin2-Rluc) and acceptor (CB1-GFP2, HERG-GFP2, and arrestin-GFP2) plasmids, and BRETeff was determined. The amount of DNA transfected was kept constant (800 ng) by the addition of pcDNA3.1. The non-interacting HERG receptor and Rluc alone were used as negative controls. GFP2-Rluc was used as a positive control. *, p < 0.001 compared with HERG-Rluc, arrestin2-GFP2, arrestin2-Rluc, and HERG-GFP2 as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test. n = 6. C, cells were transfected with arrestin2-Rluc and CB1-GFP2 or arrestin2-Rluc and HERG-GFP2 plasmids, and BRETeff was measured (time 0 h = 48 h post-transfection). *, p < 0.001 compared with arrestin2-Rluc and HERG-GFP2 as determined via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; n = 6.

FIGURE 2.

2-AG, THC, and CP treatment enhanced BRETeff between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc. A–C, BRETeff was measured over a 30-min time span in cells expressing CB1-GFP2 or HERG-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc and treated with vehicle, 500 nm O-2050, and 1 μm AEA or 2-AG (A), CBD or THC (B), and CP or WIN (C). D–I, BRETeff was measured at 10 (D–F) or 30 min (G–I) in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells expressing CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc and treated with 0.01–5.00 μm AEA or 2-AG (D and G), CBD or THC (E and H), and CP or WIN (F and I) with or without 500 nm O-2050 and O-2050 alone (J). A–C, *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle; #, p < 0.001 compared with AEA (A) or CBD (B) as determined via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; n = 6. D–I, *, p < 0.001 compared with 2-AG (G), CBD (E and H), or WIN (F and I) as determined via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; n = 6.

TABLE 2.

BRETEff potencies and efficacies of cannabinoid ligands (BRET between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc)

*, p < 0.001 compared with AEA within the time point. #, p < 0.001 compared with 2-AG within the time point; $, p < 0.001 compared with CBD within the time point; &, p < 0.001 compared with THC within the time point; §, p < 0.001 compared with WIN within the time point; †, p < 0.001 compared with 10-min within-drug treatment as determine via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test (n = 6).

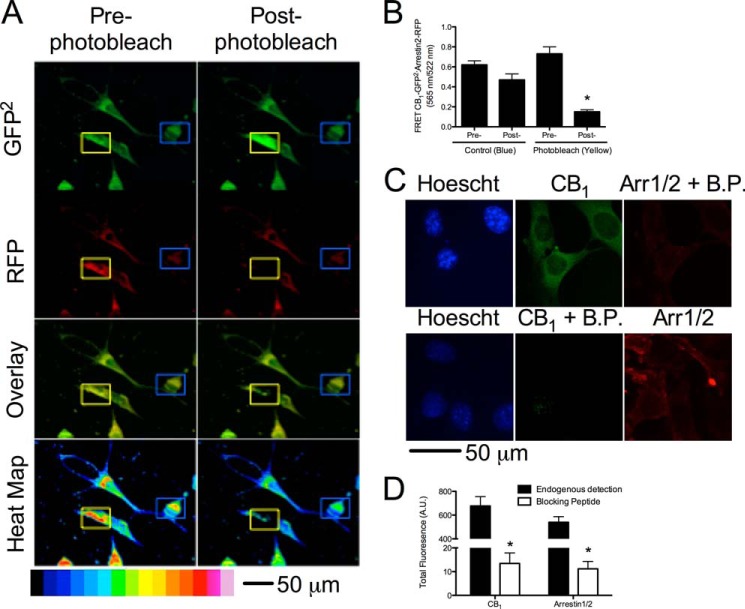

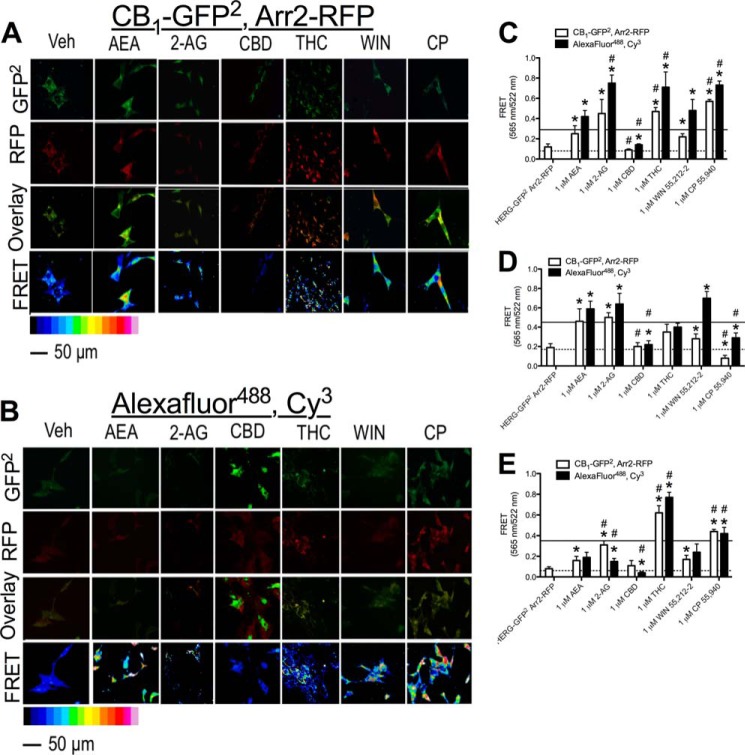

Because BRET assays quantify the level of interaction between two proteins but do not provide data on the localization of protein complexes, FRET analyses were conducted to determine the localization CB1 and arrestin2 complexes within STHdhQ7/Q7 cells in the presence of the cannabinoids studied. FRET was used to study the interaction between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP or endogenous CB1 and arrestin2 detected via fluorescent antibodies. A photobleaching experiment was conducted as a control for FRET (48). Cells were transfected with CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP. As expected, direct excitation of RFP at 543 nm for 5 min eliminated the fluorescent signal at 565 nm in a small, cytoplasmic region of interest, and the GFP2 signal in that area was enhanced, whereas the RFP and GFP2 signals in a non-photobleached region of interest were unchanged (Fig. 3, A and B) (48). The specificity of the anti-CB1 and anti-arrestin1/2 antibodies was analyzed via immunohistochemistry in the absence and presence of CB1- and arrestin1/2 antibody-blocking peptides (Fig. 3C). Fluorescence intensity was ∼60-fold greater than in the absence of blocking peptide for both CB1 and arrestin1/2 antibodies (Fig. 3D) FRET was qualitatively higher in cells treated with all cannabinoids tested (1 μm, 30 min) except CBD, indicating that interactions between CB1 and arrestin2 had increased in transfected cells overexpressing CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP (Fig. 4A) and cells endogenously expressing CB1 and arrestin2 (Fig. 4B). Quantification of total FRET for cells expressing CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP revealed that FRET was greater in cells treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, THC, CP, or WIN for 30 min than in cells treated with vehicle (Fig. 4C, dotted line). Similarly, total FRET between Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibodies (CB1) and Cy3-conjugated antibodies (arrestin2) was greater in cells treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, THC, CP, or WIN for 30 min than in cells treated with vehicle (Fig. 4C, solid line). Total FRET between Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 was reduced in cells treated with 1 μm CBD for 30 min relative to vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4C). We also observed that total FRET was greater in cells treated with 2-AG (Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 only), THC, or CP and less in cells treated with CBD than in cells treated with AEA (Fig. 4C). At the plasma membrane, FRET was greater in cells treated with AEA, 2-AG, or WIN (Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 only) and less in cells treated with CBD (Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 only) or CP compared with vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4D). Moreover, FRET was reduced in cells treated with CBD, WIN (CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP only), or CP relative to AEA-treated cells (Fig. 4D). Within the cytoplasm, FRET was greater in cells treated with AEA (CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP only), 2-AG, THC, WIN (CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP only), or CP and less in cells treated with CBD (Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 only) than in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4E). FRET within the cytoplasm was also greater in 2-AG (CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP only)-, THC-, and CP-treated cells and less in CBD-treated cells (Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 only) than in AEA-treated cells (Fig. 4E). A further comparison of FRET between the plasma membrane (Fig. 4D) and cytoplasm (Fig. 4E) demonstrates although 2-AG, THC, and CP all enhanced arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 to a greater extent than other ligands tested, THC and CP biased CB1-arrestin2 complexes toward internalization to a greater extent than 2-AG.

FIGURE 3.

Validation of the FRET assay. Cells expressing CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP were photobleached to confirm FRET. A, representative image of photobleaching in cells expressing CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP. The blue outlined boxes indicates a control area, and the yellow outlined boxes indicates an area that was photobleached. B, quantification of FRET pre- and post-photobleaching. *, p < 0.001 compared with pre-photobleaching (yellow square) as determined via unpaired t test; n = 60 from 3 independent experiments. C, representative images of immunohistochemical detection of CB1 and arrestin1/2 in the absence and presence of blocking peptides (B.P.). D, quantification of fluorescence for CB1 and arrestin1/2 in the absence and presence of blocking peptides. *, p < 0.001 compared with endogenous detection as determined via unpaired t test; n = 9 from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 4.

2-AG, THC, and CP treatment enhanced FRET between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-Rluc. Shown are representative images of FRET between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP (A) or Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 (B) in cells treated with vehicle or 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, WIN, or CP for 30 min. C–E, quantification of FRET between CB1-GFP2 and arrestin2-RFP and Alexa Fluor 488 and Cy3 from the whole cell (C), at the plasma membrane (D), and in the cytoplasm (E). *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment (dotted line represents the mean for CB1-GFP2/arrestin2-RFP vehicle-treated cells, and solid line represents the mean for Alexa Fluor 488/Cy3 vehicle-treated cells); #, p < 0.001 compared with AEA as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 60 from three independent experiments.

Analysis of FRET at 10 min revealed no significant difference between 10 and 30 min of treatment with any cannabinoid tested (data not shown). Quantification of FRET in the nucleus and dendrites of cells revealed no difference among treatments (data not shown). The cell diameter, cell area, projection length, and projection number were not different between treatment groups (n = 50; data not shown). Overall, these data demonstrate that THC and CP appear to bias CB1 toward arrestin2-mediated internalization to a greater degree than the other cannabinoid ligands tested.

Cannabinoid Ligands Biased Intracellular Signaling

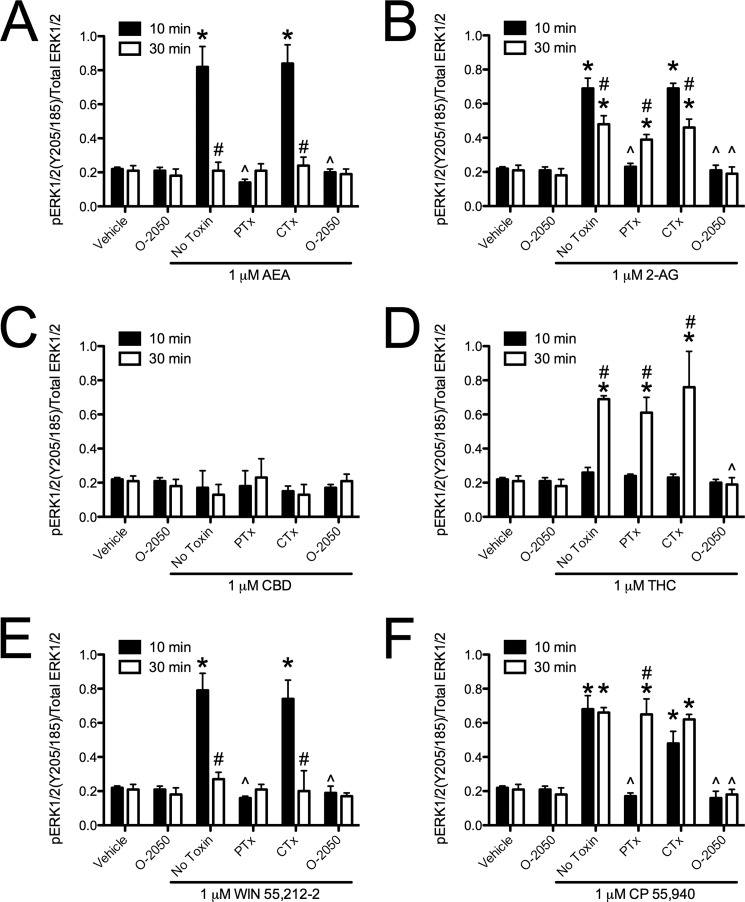

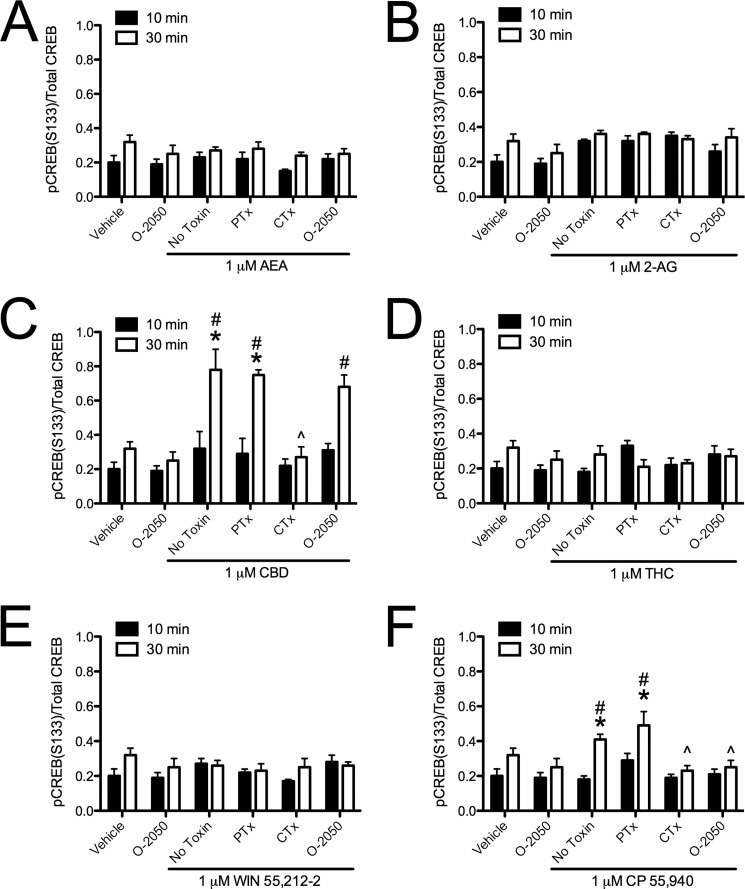

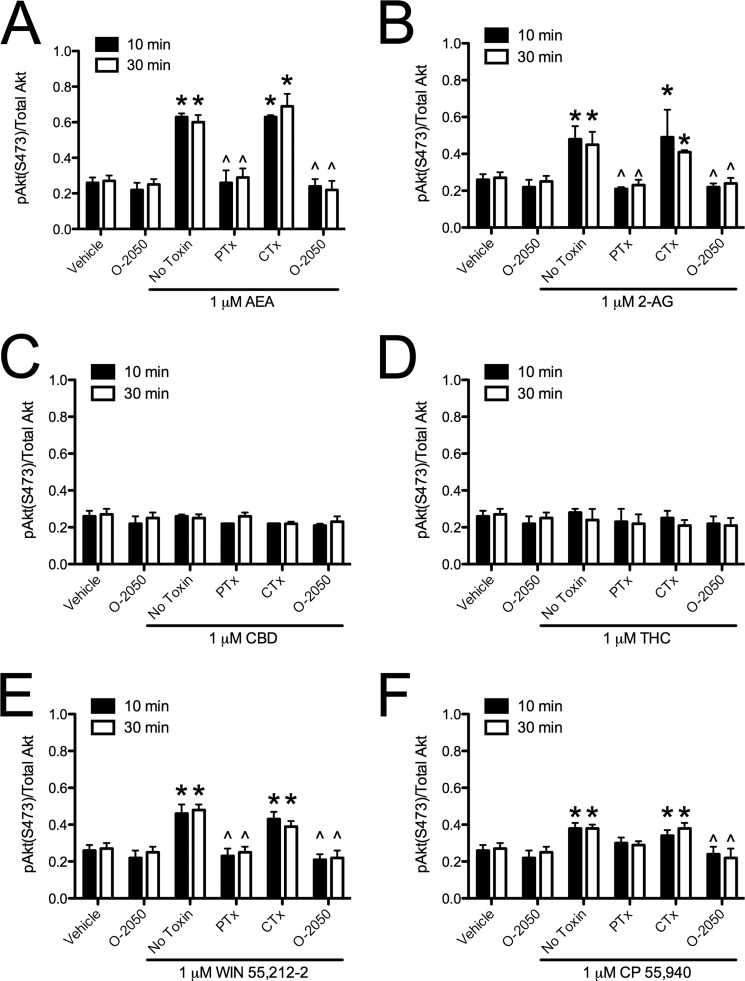

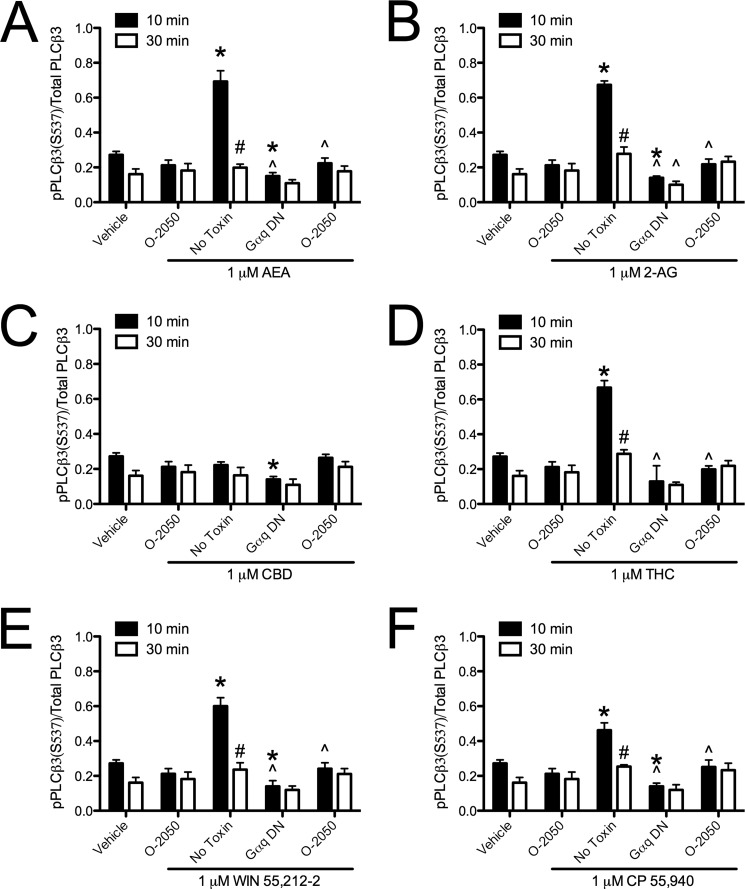

Because we had observed ligand-specific differences in CB1-arrestin2 interactions, we wanted to determine whether intracellular signaling differed among cannabinoids. Treatment with AEA or 2-AG for 10 min resulted in a PTx-and O-2050-sensitive increase in ERK phosphorylation compared with vehicle (Fig. 5, A and B). By 30 min, AEA-mediated ERK phosphorylation was not detectable, whereas O-2050-sensitive ERK phosphorylation persisted in 2-AG-treated cells and was no longer PTx-sensitive compared with vehicle-treated cells or with treatment at 10 min (Fig. 5, A and B). AEA and 2-AG treatment did not change the levels of CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 6, A and B). AEA and 2-AG treatment did increase O-2050 and PTx-sensitive Akt phosphorylation at 10 and 30 min compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 7, A and B). AEA and 2-AG also increased the CB1- and Gαq-dependent phosphorylation of PLCβ3 at 10 min compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 8, A and B). Treatment with CBD did not change ERK, Akt, or PLCβ3 phosphorylation but did increase CTx-sensitive CREB phosphorylation at 30 min compared with vehicle treatment and compared to treatment for 10 min with CBD (Figs. 5C, 6C, 7C, and 8C). CBD-mediated CREB phosphorylation was CB1-independent because it was not inhibited by O-2050. Therefore, CBD may enhance CREB activation via other cannabinoid receptors, GPCRs, or GPCR-independent mechanisms (7, 12). Like 2-AG, THC increased CB1- and Gαq-dependent phosphorylation of PLCβ3 at 10 min and CB1-dependent, PTx-insensitive ERK phosphorylation at 30 min compared with vehicle treatment and treatment at 10 min, and it did not alter CREB phosphorylation (Figs. 5D, 6D, 7D, and 8D). Unlike 2-AG, THC treatment did not increase ERK phosphorylation at 10 min or Akt phosphorylation at 10 and 30 min (Figs. 5D, 6D, 7D, and 8D). WIN and CP treatment for 10 min resulted in a PTx- and O-2050-sensitive increase in ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 5, E and F) and CB1- and Gαq-dependent phosphorylation of PLCβ3 at 10 min (Fig. 8, E and F), relative to vehicle treatment. As with AEA, ERK phosphorylation was not detected in cells treated with WIN for 30 min (Fig. 5E). CP treatment for 30 min resulted in CB1-dependent, PTx-insensitive ERK phosphorylation compared with vehicle treatment, as observed with 2-AG and THC (Fig. 5F). WIN treatment did not alter CREB phosphorylation, but CP treatment for 30 min did increase O-2050- and CTx-sensitive CREB phosphorylation relative to vehicle treatment and 10-min treatment with CP (Fig. 6, E and F). CP-dependent CREB phosphorylation was less than CBD-dependent CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 6, C and F). Both WIN and CP treatment for 10 and 30 min increased Akt phosphorylation compared with vehicle treatment but was less than either AEA or 2-AG (Fig. 7, A, B, E, and F). Therefore, AEA, 2-AG, WIN, and CP treatment resulted in Gαi/o-dependent transient ERK phosphorylation (51), Gαq-dependent transient PLCβ3 phosphorylation, and persistent Akt phosphorylation. THC treatment also resulted in Gαq-dependent transient PLCβ3 phosphorylation. Further, treatment with 2-AG, THC, and CP, the ligands that enhanced BRETeff and FRET between CB1 and arrestin2 more than the other cannabinoids tested, resulted in persistent (30 min) Gαi/o-independent ERK phosphorylation. Finally, CBD and CP treatment enhanced Gαs-mediated CREB phosphorylation, although CBD did so independent of CB1. AEA, 2-AG, THC, WIN, and CP increased the phosphorylation of ERK, CREB, Akt, or PLCβ3 via CB1 because these effects were blocked by the CB1-selective antagonist O-2050 (1). Therefore, the functional selectivity between the cannabinoids tested here is the result of ligand bias at CB1 receptors.

FIGURE 5.

Cannabinoid ligands biased CB1-dependent ERK signaling. ERK phosphorylation (pERK1/2(Tyr-205/Tyr-185)/total ERK1/2) was quantified via In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with 1 μm AEA (A), 2-AG (B), CBD (C), THC (D), WIN (E), or CP (F) for 10 or 30 min with or without 500 nm O-2050 or with 24-h pretreatment with 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx. *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment within the time point; ∧, p < 0.001 compared with the No Toxin treatment within the time point; #, p < 0.001 compared with 10 min within the drug and toxin treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

FIGURE 6.

Cannabinoid ligands biased CB1-dependent CREB signaling. CREB phosphorylation (pCREB(Ser-133)/Total CREB) was quantified via In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with 1 μm AEA (A), 2-AG (B), CBD (C), THC (D), WIN (E), or CP (F) for 10 or 30 min with or without 500 nm O-2050 or 24 h of pretreatment with 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx. *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment within time point; ∧, p < 0.001 compared with No Toxin treatment within time point; #, p < 0.001 compared with 10 min within drug and toxin treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

FIGURE 7.

Cannabinoid ligands biased CB1-dependent Akt signaling. Akt phosphorylation (pAkt(Ser-473)/total Akt) was quantified via In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with 1 μm AEA (A), 2-AG (B), CBD (C), THC (D), WIN (E), or CP (F) for 10 or 30 min with or without 500 nm O-2050 or 24 h of pretreatment with 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx. *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment within time point; ∧, p < 0.001 compared with No Toxin treatment within time point; #, p < 0.001 compared with 10 min within drug and toxin treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

FIGURE 8.

Cannabinoid ligands biased CB1-dependent PLCβ3 signaling. PLCβ3 (pPLCβ3(Ser-537)/total PLCβ3) was quantified via In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with 1 μm AEA (A), 2-AG (B), CBD (C), THC (D), WIN (E), or CP (F) for 10 or 30 min with or without 500 nm O-2050 or expressing Gαq dominant negative (Gαq DN). *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment within time point; ∧, p < 0.001 compared with No Toxin treatment within time point; #, p < 0.001 compared with 10 min within drug and toxin treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

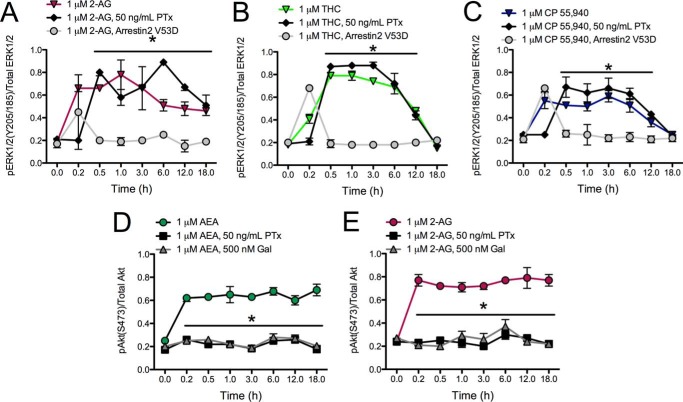

Sustained and Gαi/o-independent ERK phosphorylation occurs via arrestin2 (47). We tested this possibility by treating cells overexpressing an arrestin2 dominant negative mutant (arrestin2 V53D) with 1 μm 2-AG, THC, or CP with or without 50 ng/ml PTx (Fig. 9, A–C). We observed that PTx-insensitive ERK phosphorylation was sustained at each time point above the levels observed before drug treatment in cells treated with 2-AG (Fig. 9A) and for 12 h in cells treated with THC (Fig. 9B) or CP (Fig. 9C). However, the levels of phosphorylated ERK did not differ from basal levels (0 h) in cells expressing arrestin2 V53D. Based on these data, the sustained ERK phosphorylation observed with 2-AG, THC, and CP occurred via arrestin2-mediated signaling.

FIGURE 9.

Sustained ERK phosphorylation was arrestin2-dependent, and sustained Akt phosphorylation was Gαi/o- and Gβγ-dependent. A–C, ERK phosphorylation (pERK1/2(Tyr-205/Tyr-185)/total ERK) was measured over 18 h in cells treated with 1 μm 2-AG (A), THC (B), or CP (C) with or without 50 ng/ml PTx or in the presence of an arrestin2 dominant negative mutant (arrestin2 V53D). *, p < 0.001 compared with treatment in the presence of arrestin2 V53D, within time point as determined via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; n = 4. D and E, Akt phosphorylation (pAkt(Ser-473)/total Akt) was measured over 18 h in cells treated with 1 μm AEA (D) or 2-AG (E) with or without 50 ng/ml PTx or 500 nm gallein (Gal). *, p < 0.001 compared with cannabinoid treatment alone, within time point as determined via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; n = 4.

We also observed PTx-sensitive Akt phosphorylation in cells treated with AEA or 2-AG for 10 or 30 min. Akt phosphorylation is not commonly associated with the activation of Gαi/o-mediated signaling (52) but does occur via Gβγ-dependent activation, which is typically associated with Gαi/o (53). To determine whether this was occurring in our model system, cells were treated with 1 μm AEA or 2-AG with or without 50 ng/ml PTx or 500 nm gallein, the Gβγ inhibitor (Fig. 7, D and E). Co-treatment of AEA (Fig. 7D)- or 2-AG (Fig. 7E)-treated cells with PTx or gallein prevented Akt phosphorylation over the 18-h time period analyzed. Therefore, AEA- and 2-AG-dependent Akt phosphorylation was mediated by Gαi/o and Gβγ.

The Functional Selectivity of Cannabinoid Ligands Altered the Expression and Localization of CB1 Receptors

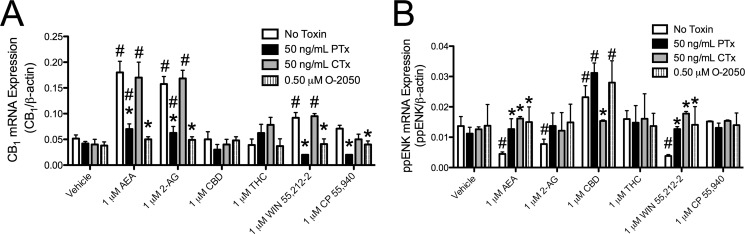

Arachidonyl-2′-chloroethylamide (ACEA), methanandamide, and AEA increased the steady-state levels of CB1 mRNA and protein via Akt and NF-κB (37). Akt activation was observed in AEA-, 2-AG-, WIN-, and CP-treated cells and not in THC- and CBD-treated cells. We hypothesized that this increase in CB1 levels was unique to those cannabinoids that increased Akt phosphorylation. To test this hypothesis, cells were treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, WIN, or CP with or without 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx or 500 nm O-2050 for 18 h, and CB1 mRNA levels were quantified relative to β-actin (Fig. 10A). AEA and 2-AG, and to a lesser extent WIN, increased CB1 mRNA levels relative to vehicle treatment, whereas CBD, THC, and CP treatment did not change CB1 mRNA levels (Fig. 10A). The increase in CB1 mRNA levels may have been less in WIN-treated cells and absent in CP-treated cells because Akt phosphorylation was lower in WIN- and CP-treated cells relative to AEA- and 2-AG-treated cells (Fig. 7), resulting in insufficient activation of this signaling pathway. In addition, the increase in CB1 mRNA levels was blocked by treatment with O-2050 or PTx and therefore occurred through CB1 and Gαi/o (Fig. 10A). Therefore, AEA, 2-AG, and WIN treatment biased CB1 signaling toward activation of Gαi/o signaling, resulting in increased CB1 mRNA levels.

FIGURE 10.

AEA and 2-AG treatment increased CB1 mRNA levels via Gαi/o, whereas CBD increased ppENK mRNA levels via Gαs. CB1 (A) and ppENK (B) mRNA levels were quantified using qRT-PCR in samples from cells treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, WIN, or CP for 18 h with or without 500 nm O-2050 or 24 h pretreatment with 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx. CB1, and ppENK levels were normalized to β-actin. *, p < 0.001 compared with No Toxin within treatment group; #, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle within toxin treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

CBD and CP treatment increased CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 6, C and F). Therefore, we wanted to know whether treatment with CBD or CP would increase preproenkephalin (ppENK) expression, which is known to be CREB-dependent (54, 55). ppENK mRNA levels were quantified in cells treated with 1 μm AEA, 2-AG, CBD, THC, WIN, or CP with or without 50 ng/ml PTx or CTx or 500 nm O-2050 for 18 h. AEA, 2-AG, and WIN treatment were associated with a CB1-dependent decrease in ppENK mRNA levels, whereas CBD treatment increased ppENK mRNA levels compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 10B). The CBD-mediated increase in ppENK mRNA levels was CB1-independent, because it was not inhibited by O-2050 (Fig. 10B). CP treatment did not affect ppENK mRNA levels (Fig. 10B). CBD treatment resulted in greater CREB phosphorylation than CP treatment (Fig. 6, C and F). Therefore, CP treatment may have failed to increase ppENK mRNA levels because the magnitude of CREB phosphorylation was too low. Based on these data, AEA-, 2-AG-, and WIN-dependent activation of Gαi/o through CB1 inhibited CREB-mediated gene expression, whereas CBD-mediated, CB1-independent activation of Gαs increased CREB-mediated gene expression.

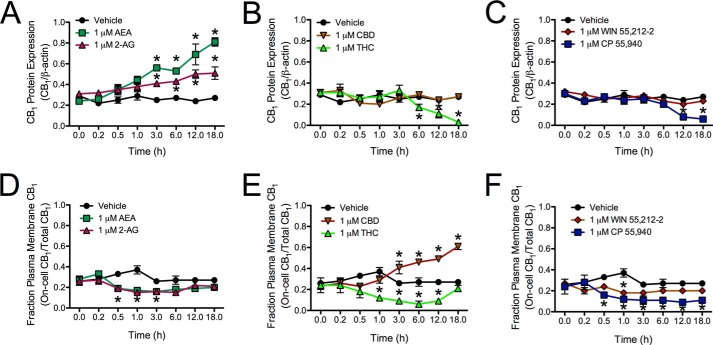

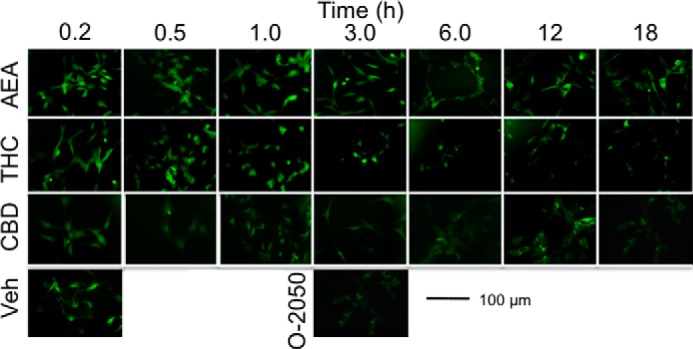

Increased CB1 mRNA levels translated to increased CB1 protein abundance, as determined by On- and In-cellTM Western analyses. Treatment with 1 μm AEA or 2-AG resulted in increased CB1 levels within 3 h compared with the 0 h measurement or with vehicle treatment within the time point, and this increase was still observed at 18 h (Fig. 11A). In contrast, treatment with 1 μm THC or CP resulted in decreased CB1 levels by 6 h (THC) and 12 h (CP) compared with the 0 h measurement or vehicle control (Fig. 11, B and C). Treatment with 1 μm CBD or WIN did not change CB1 protein levels (Fig. 11, B and C). CB1 localization was also analyzed over an 18-h treatment period. The fraction of CB1 receptors at the membrane of AEA- and 2-AG-treated cells was decreased between 0.5 and 3 h compared with the 0 h time point or vehicle-treated cells, which returned to basal levels by 6 h (Fig. 11D). A decrease in the fraction of CB1 receptors at the membrane was also observed in THC- and WIN-treated cells between 1 and 12 h (THC) and at 1 h (WIN) compared with the 0 h time point or vehicle-treated cells, which returned to basal levels by 18 h (THC) and 3 h (WIN) (Fig. 11, E and F). Treatment with CBD increased the fraction of CB1 receptors at the membrane between 3 and 18 h relative to the 0 h time point or vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 11E). In contrast, treatment with CP resulted in a sustained decrease in the fraction of CB1 receptors at the membrane beginning at 0.5 h and persisting to 18 h, as compared with the 0 h time point and vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 11F). CB1 receptor localization was also examined via confocal microscopy in cells expressing CB1-GFP2 that were treated with 1 μm AEA, THC, or CBD for 10 or 30 min or 1, 3, 6, 12, or 18 h. Similar to the observations made in Fig. 11D, CB1-GFP2 localization shifted from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm and back to the plasma membrane in cells treated with AEA for 18 h (Fig. 12). In contrast to the AEA-treated cells, CB1-GFP2 was first internalized and subsequently degraded, as indicated by decreased fluorescence, in THC-treated cells (Fig. 12). In CBD-treated cells CB1-GFP2 fluorescence at the plasma membrane gradually increased over the 18 h observation period (Fig. 12). Similarly, CB1-GFP2 was localized to the plasma membrane in cells treated with 500 nm O-2050 for 3 h (Fig. 12). Therefore, although AEA and THC treatment affected CB1 signaling and internalization, CBD did not affect CB1 internalization and CBD-mediated signaling was CB1-independent.

FIGURE 11.

AEA and 2-AG treatment increased CB1 protein levels, whereas THC and CP treatment promoted CB1 degradation. A–C, CB1 protein levels (relative to β-actin) were determined using In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with vehicle, 1 μm AEA or 2-AG (A), CBD or THC (B), and WIN or CP (C) for 18 h. D–F, the percentage of cell surface CB1 receptors relative to total CB1 receptor levels was determined using On- and In-cellTM Western assays in cells treated with vehicle, 1 μm AEA or 2-AG (D), CBD or THC (E), and WIN or CP (F) for 18 h. *, p < 0.001 compared with vehicle treatment within time point and compared with 0 h time point within treatment as determined via two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test; n = 4.

FIGURE 12.

CB1 localization was assessed in cells expressing CB1-GFP2. This is a representative images of STHdhQ7/Q7 cells expressing CB1-GFP2 and treated with vehicle, 1 μm AEA, THC, or CBD for the lengths of time indicated and 500 nm O-2050 for 3 h. Images are from one of four independent experiments.

In conclusion, the endocannabinoids, AEA and 2-AG, facilitated an increase in CB1 mRNA and protein via Gαi/o and Gβγ. WIN also activated Gαi/o and Gβγ signaling but to a lesser extent than AEA and 2-AG. Treatment with the phytocannabinoid THC and the synthetic cannabinoid CP did not alter CB1 mRNA levels but did lead to a decrease in CB1 protein levels over the 18-h time period analyzed. CP also enhanced Gαs signaling via CB1. CBD-mediated Gαs signaling occurred independent of CB1 as observed elsewhere (8).

DISCUSSION

CB1-mediated Intracellular Signaling Was Ligand-specific

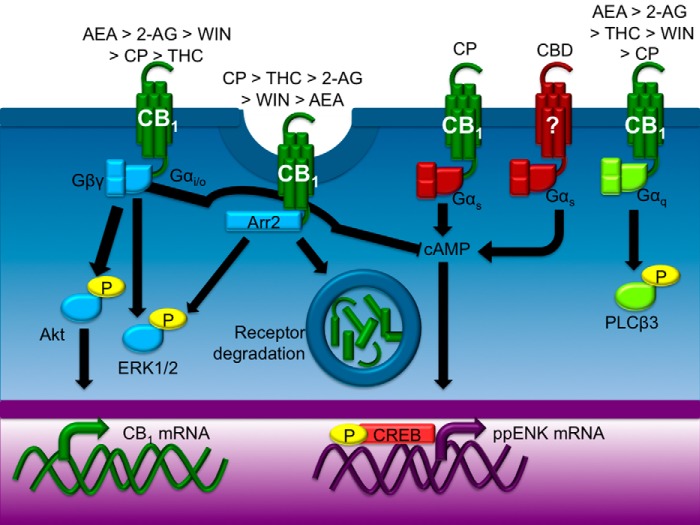

The goal of this study was to compare the CB1-mediated functional selectivity of six cannabinoids in a cell line that models striatal medium spiny projection neurons endogenously expressing CB1. Each ligand displayed functional selectivity for a subset of intracellular signaling pathways (see summary in Fig. 13). With the exception of CBD-dependent Gαs signaling, this functional selectivity was CB1-dependent.

FIGURE 13.

Cannabinoid ligands biased CB1-depending signal transduction. Each cannabinoid tested here biased CB1 signaling toward different pathways. The endocannabinoids AEA and 2-AG promoted Gαi/o-dependent ERK and Akt activation more effectively than other cannabinoids tested. THC and CP were the most efficacious ligands with regard to CB1-arrestin2 interactions, but 2-AG, WIN, and AEA also promoted interactions between CB1 and arrestin2 above the level observed in vehicle-treated cells. CBD appeared to inhibit the internalization of CB1. CBD treatment enhanced Gαs-dependent CREB phosphorylation independent of CB1, whereas CP-dependent CREB phosphorylation occurred through CB1. AEA, 2-AG, THC, WIN, and CP promoted Gαq-dependent transient PLCβ3 activation.

2-AG, THC, and CP enhanced the interaction between CB1 and arrestin2 to a greater extent than other cannabinoids tested, suggesting a high degree of interaction between the population of CB1 and arrestin2 molecules in the in vitro system following 30 min of treatment with these compounds. The relative BRETeff was a conservative estimate of the interaction between CB1 and arrestin2, because endogenous CB1 and arrestin2 would have competed with their labeled counterparts in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells in the BRET assays. These observations differ from previous reports that CB1 interacts weakly with arrestins in U2OS, CHO, and HEK cell heterologous expression systems treated with WIN or CP for 5 min (33) or 2 h (33). Previous studies also observed that recruitment of arrestins to CB1 occurs over a wider range of ligand concentrations (1 × 10−10-1 × 10−6 m) (32, 33) than that observed here (1 × 10−8-1 × 10−5 m). The variability between our results and previous reports may reflect differences between the functionality of CB1 in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells and CB1 overexpression in U2OS, CHO, or HEK cells (33). In addition, BRET2, used in this study, is a more sensitive assay for detecting protein-protein interactions compared with the Tango and PathHunter reporter assays used previously (32). Moreover, previous studies examined the recruitment of arrestin3 (β-arrestin2) in HEK cells (33) and not arrestin2.

At 1 μm, AEA, 2-AG, WIN, and CP biased CB1 signaling toward Gαi/o-mediated ERK phosphorylation to a greater degree than other cannabinoids tested. The consequence of this functional selectivity is that transient ERK signaling was enhanced by endocannabinoids compared with other cannabinoids tested, whereas sustained ERK signaling from 10 to 30 min through arrestin2 was enhanced by 2-AG, THC, and CP and not by AEA, CBD, or WIN. Other studies have also reported that transient ERK activation occurs via Gαi/o in the N18TG2 mouse neuronal cell line (56) and in HEK 293 cells stably expressing CB1 (51). In our studies CB1 receptors recruited arrestin2, leading to sustained ERK signaling, whereas previous studies have found that sustained ERK signaling is receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent (56).

AEA and 2-AG activated Akt via Gαi/o- and Gβγ-dependent pathways. This resulted in increased CB1 mRNA and protein levels. Although WIN and CP treatment also resulted in Gαi/o-dependent ERK phosphorylation and Gβγ-dependent Akt phosphorylation, the magnitude of Gβγ activation was less following WIN and CP treatment than that observed following treatment with AEA and 2-AG. The net result was that WIN and CP treatment did not lead to significantly increased CB1 mRNA and protein levels.

In addition to the activation of Gαi/o, AEA, 2-AG, WIN, THC, and CP enhanced transient Gαq-coupled PLCβ3 phosphorylation. Few studies have examined direct coupling of CB1 to Gαq (25, 57). Coupling of CB1 to Gαq has been reported in HEK 293 cells stably expressing CB1 (25) and human trabecular meshwork cells (58). In these studies, the authors observed transient, Gαq-dependent Ca2+ efflux following stimulation of CB1 with WIN (25, 57), which is an indirect measure of Gαq coupling. In support of studies that have indirectly measured CB1 coupling to Gαq via Ca2+ efflux, the work here measured PLCβ3 activation, which is a direct effect of Gαq. Because Gαq signaling may affect cellular function, future studies examining CB1 signaling should determine whether CB1 couples to Gαq in other model systems.

CBD treatment resulted in GαS- and CREB-dependent expression of ppENK (7, 12). CBD signaling was independent of CB1, as demonstrated previously by the inability of the direct antagonist O-2050 to block agonist-dependent Gαs signaling (8). Although CBD has a relatively low affinity for CB1 (6), CBD has been shown to act as an agonist and antagonist at the type 2 cannabinoid receptor, an adenosine A2A agonist, a 5HT1A agonist, and a modulator of FAAH and monoacylglycerol lipase activity (MAGL) (6–8, 58). STHdhQ7/Q7 cells express adenosine A2A and 5HT1A receptors and FAAH (36, 37). The inability of O-2050 to block Gαs signaling indicates that CBD acted at non-CB1 targets in STHdhQ7/Q7 cells. In our assays, CBD treatment increased CB1 levels at the plasma membrane but did not affect CB1-dependent signaling through Gαi/o or Gαq. CBD is being investigated for its utility as an anti-epileptic (8) and an anti-inflammatory (12) and for its neuromodulatory activities in vivo (7, 8). CBD has a relatively safe side effect profile compared with THC and other cannabinoids (7, 8). Our work suggests that CBD has little effect on CB1-dependent signaling. The fact that we observed that CBD selectively increased CREB-dependent gene expression may also have therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases, where CREB-dependent gene expression is dysregulated (6, 8, 37).

Unlike CBD, CP-dependent CREB phosphorylation occurred via CB1. Although CB1 does not typically signal through Gαs, CP may have promoted a conformational change in the receptor that favored Gαs binding. Alternatively, CP treatment may promote the dimerization of CB1 with other GPCRs that signal through Gαs. CB1 is known to homodimerize with CB1 and CB1 splice variants (40) and heterodimerize with other receptors including the dopamine D2 receptor (37, 43, 59). STHdhQ7/Q7 cells express dopamine D2 receptors and CB1-D2 dimerization may contribute to the actions of CP in these cells (59). Together, these data demonstrate that CB1 is a receptor that couples to multiple G proteins within a single cell type (pleiotropic).

CB1-mediated Signaling Had Immediate and Sustained Components

In addition to showing cannabinoid ligand bias, CB1 signaling was also time-dependent. Gαi/o and Gαq signaling was transient, being detected at 10 min and returning to basal levels at 30 min. Transient CB1-dependent activation of Gαi/o and Gαq signaling has been observed elsewhere in HEK 293 cells stably expressing CB1 (25, 51). In contrast, Gαs signaling was not detected before 30 min. The association between CB1 and arrestin2 peaked shortly after 10 min for all ligands tested and remained high for 30 min relative to vehicle control, demonstrating that the pleiotropically coupled CB1 receptor switches between G protein signaling and arrestin signaling within ∼30 min of ligand administration and that this switch is ligand-specific. Over an 18-h treatment period, THC, CP, and 2-AG treatment resulted in CB1 receptor internalization (beginning at 30 min), but only THC and CP treatment resulted in decreased CB1 receptor protein levels (beginning at 12 h). This difference may be due to the higher affinity of THC and CP for CB1 compared with 2-AG (60), which implies that 2-AG is a “fast-off” cannabinoid relative to THC or CP (30–32). In vivo, 2-AG is ∼1000 times more abundant than AEA (60–62). 2-AG is likely to have a greater effect on the arrestin-mediated recycling of CB1 between the membrane and intracellular space relative to AEA. Overall, the biased agonism displayed by the six cannabinoids tested here in an in vitro model of striatal neurons supports the hypothesis that individual ligands promote unique conformational changes in the CB1 receptor leading to functionally divergent intracellular effects such as G protein-coupled signaling, arrestin recruitment, receptor trafficking, and gene expression (22, 29, 31–33).

The Effect of Cannabinoids Is Brain Region- and Agonist-specific

We observed increased CB1 mRNA and protein levels following 18 h of treatment with 2-AG or AEA in an in vitro cell culture model of striatal neurons. In vivo, CB1 receptor binding does not differ between FAAH knock-out mice and wild-type littermates in the striatum, hippocampus, or cerebellum when treated with vehicle or AEA for 5 consecutive days (19). Further, CB1 receptor binding decreases in these brain regions of FAAH knock-out mice treated with THC for 5 consecutive days (19). MAGL knock-out mice and mice treated for 6 days with the MAGL inhibitor JZL184 display decreased CB1 receptor binding in the cortex, hippocampus, and periaqueductal gray but no difference in the striatum (21). In vivo then, the alteration of CB1 level depends on the brain region, animal genotype, and duration of treatment, as well as the cannabinoid ligand (19–21). Inhibition of MAGL (5 days), the principle regulator of 2-AG levels, results in functional antagonism of CB1, whereas inhibition of FAAH, the principle regulator of AEA levels, maintains CB1 signaling (19–21). Subchronic or chronic exposure to exogenous cannabinoids, such as THC, and high potency cannabinoids decreases CB1 receptor binding (19–21). The down-regulation and desensitization of CB1 receptor following repeated THC or WIN treatment are more pronounced in the hippocampus compared with the striatum (63, 64). CB1 desensitization and arrestin3 (β-arrestin2) recruitment also vary widely among brain regions (65). FAAH knock-out mice show less CB1 down-regulation and desensitization following AEA treatment compared with THC-treated FAAH knock-out mice (19). CB1 internalization is also promoted by WIN more than methanandamide in primary rat hippocampal neurons (66). THC-mediated desensitization is faster than WIN-, CP-, and 2-AG-mediated desensitization in HEK 293 cells stably expressing CB1 and primary neuronal cultures (67). In contrast, AEA-mediated CB1 desensitization is slower than that of WIN-, CP-, and 2-AG (67). Endogenous cannabinoids, specifically AEA, may have a different effect on CB1 levels than other cannabinoids. We do not yet know whether there is a difference in the brain region-specific effect on CB1 mRNA and protein levels under various treatment regimens in vivo.

There is the potential to exploit biased agonism at CB1. Effects such as receptor internalization via arrestin2, Gαi/o-mediated increases in CB1, Gαq-mediated modulation of Ca2+ release, Gαs-mediated CREB activation, and CB1 protein down-regulation could be selected or avoided according to their usefulness in different disease states. This could lead to the development of therapeutics that avoid the psychoactive effects of cannabinoids and promote their neuroprotective effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jaime Wertman and Kelsie Gilles for critical evaluation of the data, figure presentations, and manuscript.

This work was supported by Partnership Grant ROP-97185 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, and the Huntington Society of Canada (HSC) (to E. M. D.-W.), Operating Grant MOP-97768 from CIHR (to M. E. M. K.), and Grant RGPIN-355310-2013 from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (to D. J. D.).

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonylglycerol

- AEA

- anandamide

- BRET2

- bioluminescence resonance energy transfer2

- CB1

- type 1 cannabinoid receptor

- CBD

- cannabidiol

- CP

- CP55,940

- CTx

- cholera toxin

- FAAH

- fatty acid amide hydrolase

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- MAGL

- monoacylglycerol lipase

- ppENK

- preproenkephalin

- PTx

- pertussis toxin

- Rluc

- Renilla luciferase

- THC

- Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- WIN

- WIN55,212-2

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-O-(thiotriphosphate)

- HERG

- human ether-a-go-go-related gene

- qRT

- quantitative reverse transcriptase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pertwee R. G. (2008) Ligands that target cannabinoid receptors in the brain: from THC to anandamide and beyond. Addict. Biol. 13, 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bosier B., Muccioli G. G., Hermans E., Lambert D. M. (2010) Functionally selective cannabinoid receptor signaling: therapeutic implications and opportunities. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cupini L. M., Costa C., Sarchielli P., Bari M., Battista N., Eusebi P., Calabresi P., Maccarrone M. (2008) Degradation of endocannabinoids in chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 186–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kinsey S. G., Naidu P. S., Cravatt B. F., Dudley D. T., Lichtman A. H. (2011) Fatty acid amide hydrolase blockade attenuates the development of collagen-induced arthritis and related thermal hyperalgeisa in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 99, 718–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pazos M. R., Sagredo O., Fernández-Ruiz J. (2008) The endocannabinoid system in Hungtington's disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 2317–2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Devinsky O., Cilio M. R., Cross H., Fernandez-Ruiz J., French J., Hill C., Katz R., Di Marzo V., Jutras-Aswad D., Notcutt W. G., Martinez-Orgado J., Robson P. J., Rohrback B. G., Thiele E., Whalley B., Friedman D. (2014) Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia 55, 791–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costa B., Trovato A. E., Comelli F., Giagnoni G., Colleoni M. (2007) The non-psychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an orally effective therapeutic agent in rat chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 556, 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones N. A., Hill A. J., Smith I., Bevan S. A., Williams C. M., Whalley B. J., Stephens G. J. (2010) Cannabidiol displays antiepileptiform and antiseizure properties in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332, 569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cota D., Marsicano G., Lutz B., Vicennati V., Stalla G. K., Pasquali R., Pagotto U. (2003) Endogenous cannabinoid system as a modulator of food intake. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 27, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Welch S. P., Eads M. (1999) Synergistic interactions of endogenous opioids and cannabinoid systems. Brain Res. 848, 183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubino T., Viganò D., Premoli F., Castiglioni C., Bianchessi S., Zippel R., Parolaro D. (2006) Changes in expression of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and β-arrestins in mouse brain during cannabinoid tolerance. Mol. Neurobiol. 33, 199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magen I., Avraham Y., Ackerman Z., Vorobiev L., Mechoulam R., Berry E. M. (2009) Cannabidiol ameliorates cognitive and motor impairments in mice with bile duct ligation. J. Hepatol. 51, 528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kearn C. S., Greenberg M. J., DiCamelli R., Kurzawa K., Hillard C. J. (1999) Relationships between ligand affinities for the cerebellar cannabinoid receptor CB1 and the induction of GDP/GTP exchange. J. Neurochem. 72, 2379–2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bosier B., Hermans E., Lambert D. (2008) Differential modulation of AP-1- and CRE-driven transcription by cannabinoid agonists emphasizes functional selectivity at the CB1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 155, 24–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Breivogel C. S., Selley D. E., Childers S. R. (1998) Cannabinoid receptor agonist efficacy for stimulating [35S]GTPγS binding to rat cerebellar membranes correlates with aongist-induced decreases in GDP affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16865–16873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ryan W., Singer M., Razdan R. K., Compton D. R., Martin B. R. (1995) A novel class of potent tetrahydrocannabinols (THCS): 2′-yne-Δ8- and Δ9-THCS. Life Sci. 56, 2013–2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiley J. L., Compton D. R., Dai D., Lainton J. A., Phillips M., Huffman J. W., Martin B. R. (1998) Structure-activity relationships of indole- and pyrrole-derived cannabinoids. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 285, 995–1004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith P. B., Compton D. R., Welch S. P., Razdan R. K., Mechoulam R., Martin B. R. (1994) The pharmacological activity of anandamide, a putative endogenous cannabinoid, in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 270, 219–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Falenski K. W., Thorpe A. J., Schlosburg J. E., Cravatt B. F., Abdullah R. A., Smith T. H., Selley D. E., Lichtman A. H., Sim-Selley L. J. (2010) FAAH−/− mice display differential tolerance, dependence, and cannabinoid receptor adaptation after Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and anandamide administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 1775–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long J. Z., Li W., Booker L., Burston J. J., Kinsey S. G., Schlosburg J. E., Pavón F. J., Serrano A. M., Selley D. E., Parsons L. H., Lichtman A. H., Cravatt B. F. (2009) Selective blockade of 2-arachidonylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schlosburg J. E., Blankman J. L., Long J. Z., Nomura D. K., Pan B., Kinsey S. G., Nguyen P. T., Ramesh D., Booker L., Burston J. J., Thomas E. A., Selley D. E., Sim-Selley L. J., Liu Q. S., Lichtman A. H., Cravatt B. F. (2010) Chronic monoacylglycerol lipase blockade causes functional antagonism of the endocannabinoid system. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1113–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glass M., Northup J. K. (1999) Agonist selective regulation of G proteins by cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 1362–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mukhopadhyay S., Howlett A. C. (2005) Chemically distinct ligands promote differential CB1 cannabinoid receptor-Gi protein interactions. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 2016–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bonhaus D. W., Chang L. K., Kwan J., Martin G. R. (1998) Dual activation and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by cannabinoid receptor agonists: evidence for agonist-specific trafficking of intracellular responses. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 287, 884–888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lauckner J. E., Hille B., Mackie K. (2005) The cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2 increases intracellular calcium via CB1 receptor coupling to Gq/11 G proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19144–19149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anavi-Goffer S., Fleischer D., Hurst D. P., Lynch D. L., Barnett-Norris J., Shi S., Lewis D. L., Mukhopadhyay S., Howlett A. C., Reggio P. H., Abood M. E. (2007) Helix 8 Leu in the CB1 cannabinoid receptor contributes to selective signal transduction mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25100–25113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Georgieva T., Devanathan S., Stropova D., Park C. K., Salamon Z., Tollin G., Hruby V. J., Roeske W. R., Yamamura H. I., Varga E. (2008) Unique agonist-bound cannabinoid CB1 receptor conformations indicate agonist specificity in signaling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 581, 19–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bakshi K., Mercier R. W., Pavlopoulos S. (2007) Interaction of a fragment of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor C terminus with arrestin-2. FEBS Lett. 581, 5009–5016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Varga E. V., Georgieva T., Tumati S., Alves I., Salamon Z., Tollin G., Yamamura H. I., Roeske W. R. (2008) Functional selectivity in cannabinoid signaling. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 1, 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singh S. N., Bakshi K., Mercier R. W., Makriyannis A., Pavlopoulos S. (2011) Binding between a distal C-terminus fragment of cannabinoid receptor 1 and arrestin-2. Biochemistry 50, 2223–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin W., Brown S., Roche J. P., Hsieh C., Celver J. P., Kovoor A., Chavkin C., Mackie K. (1999) Distinct domains of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor mediate desensitization and internalization. J. Neurosci. 19, 3773–3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van der Lee M. M., Blomenröhr M., van der Doelen A. A., Wat J. W., Smits N., Hanson B. J., van Koppen C. J., Zaman G. J. (2009) Pharmacological characterization of receptor redistribution and β-arrestin recruitment assays for the cannabinoid receptor 1. J. Biomol. Screen. 14, 811–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vrecl M., Nørregaard P. K., Almholt D. L., Elster L., Pogacnik A., Heding A. (2009) β-arrestin-based BRET2 screening assay for the “non”-β-arrestin binding CB1 receptor. J. Biomol. Screen. 14, 371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bosier B., Tilleux S., Najimi M., Lambert D. M., Hermans E. (2007) Agonist selective modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression by cannabinoid ligands in a murine neuroblastoma cell line. J. Neurochem. 102, 1996–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bosier B., Lambert D. M., Hermans E. (2008) Reciprocal influences of CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonists on ERK and JNK signalling in N1E-115 cells. FEBS Lett. 582, 3861–3867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trettel F., Rigamonti D., Hilditch-Maguire P., Wheeler V. C., Sharp A. H., Persichetti F., Cattaneo E., MacDonald M. E. (2000) Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh(Q111) striatal cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2799–2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laprairie R. B., Kelly M. E., Denovan-Wright E. M. (2013) Cannabinoids increase type 1 cannabinoid receptor expression in a cell culture model of striatal neurons: Implications for Huntington's disease. Neuropharmacology 72, 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Milligan G., Unson C. G., Wakelam M. J. (1989) Cholera toxin treatment produces down-regulationof the α-subunit of the stimulatory guanine-nucleotide-binding protein (Gs). Biochem. J. 262, 643–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McKenzie F. R., Milligan G. (1991) Cholera toxin impairment of opioid-mediated inhibitionof adenylate cyclase in neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid cells is due to a toxin-induced decrease in opioid receptor levels. Biochem. J. 275, 175–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bagher A. M., Laprairie R. B., Kelly M. E., Denovan-Wright E. M. (2013) Co-expression of the human cannabinoid receptor coding region splice variants (hCB1) affects the function of hCB1 receptor complexes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 721, 341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fernández-Ruiz J., Gómez M., Hernández M., de Miguel R., Ramos J. A. (2004) Cannabinoids and gene expression during development. Neurotox. Res. 6, 389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Laprairie R. B., Kelly M. E., Denovan-Wright E. M. (2012) The dynamic nature of type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1) gene transcription. Br. J. Pharmacol. 167, 1583–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hudson B. D., Hébert T. E., Kelly M. E. (2010) Physical and functional interaction between CB1 cannabinoid receptors and β2-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 627–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lavoie C., Mercier J. F., Salahpour A., Umapathy D., Breit A., Villeneuve L. R., Zhu W. Z., Xiao R. P., Lakatta E. G., Bouvier M., Hébert T. E. (2002) β1/β2-adrenergic receptor heterodimerization regulates β2-adrenergic receptor internalization and ERK signaling efficacy. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35402–35410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dupré D. J., Thompson C., Chen Z., Rollin S., Larrivée J. F., Le Gouill C., Rola-Pleszczynski M., Stanková J. (2007) Inverse agonist-induced signaling and down-regulation of the platelet-activating factor receptor. Cell. Signal. 19, 2068–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ramsay D., Kellett E., McVey M., Rees S., Milligan G. (2002) Homo- and hetero-oligomeric interactions between G-protein-coupled receptors in living cells monitored by two variants of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET): hetero-oligomers between receptor subtypes form more efficiently than between less closely related sequences. Biochem. J. 365, 429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. James J. R., Oliveira M. I., Carmo A. M., Iaboni A., Davis S. J. (2006) A rigorous experimental framework for detecting protein oligomerization using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat. Methods 3, 1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu H. Y., Hudry E., Hashimoto T., Uemura K., Fan Z. Y., Berezovska O., Grosskreutz C. L., Bacskai B. J., Hyman B. T. (2012) Distinct dendritic spine and nuclear phases of calcineurin activation after exposure to amyloid β revealed by novel FRET assay. J. Neurosci. 32, 5298–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knowles R. B., Chin J., Ruff C. T., Hyman B. T. (1999) Demonstration by fluorescence resonance energy transfer of a close association between activated MAP kinase and neurofibrilary tangles: implications for MAP kinase activation in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 1090–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blázquez C., Chiarlone A., Sagredo O., Aguado T., Pazos M. R., Resel E., Palazuelos J., Julien B., Salazar M., Börner C., Benito C., Carrasco C., Diez-Zaera M., Paoletti P., Díaz-Hernández M., Ruiz C., Sendtner M., Lucas J. J., de Yébenes J. G., Marsicano G., Monory K., Lutz B., Romero J., Alberch J., Ginés S., Kraus J., Fernández-Ruiz J., Galve-Roperh I., Guzmán M. (2011) Loss of striatal type 1 cannabinoid receptors is a key pathogenic factor in Huntington's disease. Brain 134, 119–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Daigle T. L., Kearn C. S., Mackie K. (2008) Rapid CB1 cannabinoid receptor desensitization defines the time course of ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling. Neuropharmacology 54, 36–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shenoy S. K., Drake M. T., Nelson C. D., Houtz D. A., Xiao K., Madabushi S., Reiter E., Premont R. T., Lichtarge O., Lefkowitz R. J. (2006) β-Arrestin-dependent, G-protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the β2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Obara Y., Okano Y., Ono S., Yamauchi A., Hoshino T., Kurose H., Nakahata N. (2008) βγ subunits of G(i/o) suppress EGF-induced ERK5 phosphorylation, whereas ERK1/2 phosphorylation is enhanced. Cell. Signal. 20, 1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Simpson J. N., McGinty J. F. (1995) Forskolin induces preproenkephalin and preprodynorphin mRNA in rat striatum as demonstrated by in situ histochemistry. Synapse 19, 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gu G., Rojo A. A., Zee M. C., Yu J., Simerly R. B. (1996) Hormonal regulation of CREB phosphorylation anteroventral periventricular nucleus. J. Neurosci. 16, 3035–3044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dalton G. D., Howlett A. C. (2012) Cannabinoid CB1 receptors transactivate multiple receptor tyrosine kinases and regulate serine/threonine kinases to activate ERK in neuronal cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 2497–2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McIntosh B. T., Hudson B., Yegorova S., Jollimore C. A., Kelly M. E. (2007) Agonist-dependent cannabinoid receptor signaling in human trabecular meshwork cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 152, 1111–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]