Background: Regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling is critical for maintaining the immune response at an appropriate level.

Results: CD14 is an endogenous ligand for CD33, and their binding inhibits uptake of LPS and TLR4-mediated signaling.

Conclusion: CD14 controls TLR4-mediated signaling through the ligation with CD33.

Significance: CD33 plays an essential role in regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling.

Keywords: Dendritic Cell, Innate Immunity, Lectin, NF-kappaB, Signaling, Toll-like Receptor (TLR)

Abstract

When monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells (imDCs) were stimulated with LPS in the presence of anti-CD33/Siglec-3 mAb, the production of IL-12 and phosphorylation of NF-κB decreased significantly. The cell surface proteins of imDCs were chemically cross-linked, and CD33-linked proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. It was CD14 that was found to be cross-linked with CD33. A proximity ligation assay also indicated that CD33 was colocalized with CD14 on the cell surface of imDCs. Sialic acid-dependent binding of CD33 to CD14 was confirmed by a plate assay using recombinant CD33 and CD14. Three types of cells (HEK293T cells expressing the LPS receptor complex (Toll-like receptor (TLR) cells), and the LPS receptor complex plus either wild-type CD33 (TLR/CD33WT cells) or mutated CD33 without sialic acid-binding activity (TLR/CD33RA cells)) were prepared, and then the binding and uptake of LPS were investigated. Although the level of LPS bound on the cell surface was similar among these cells, the uptake of LPS was reduced in TLR/CD33WT cells. A higher level of CD14-bound LPS and a lower level of TLR4-bound LPS were detected in TLR/CD33WT cells compared with the other two cell types, probably due to reduced presentation of LPS from CD14 to TLR4. Phosphorylation of NF-κB after stimulation with LPS was also compared. Wild-type CD33 but not mutated CD33 significantly reduced the phosphorylation of NF-κB. These results suggest that CD14 is an endogenous ligand for CD33 and that ligation of CD33 with CD14 modulates with the presentation of LPS from CD14 to TLR4, leading to down-regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling.

Introduction

It is well established that immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs),2 are activated by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are essential for host defense, because they initiate innate immunity (1, 2). LPS is a constituent of the outer membrane of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria (3). The LPS receptor is a multiple complex comprising at least three proteins, CD14, TLR4, and MD-2. CD14 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein expressed on leukocytes (3). It is agreed that CD14 plays a role in effective presentation of LPS to TLR4 (4, 5). Ligation of LPS with TLR4 promotes the NF-κB-mediated production of proinflammatory cytokines. The LPS-NF-κB pathway is one of the key mediators of TLR-induced signal transduction (6). Because LPS is a potential immune activator and may be fatal, the response to LPS must be tightly regulated to maintain the immune response at an appropriate level (7, 8).

Many immune cells express a group of immunoglobulin family receptors that negatively regulate immune cell activation. Signaling through activation receptors is modulated by these inhibitory receptors. One of the candidates is the siglecs, a sialic acid-binding Ig (I)-like lectin family. Siglecs are characterized by an N-terminal V-set Ig-like domain that mediates sialic acid binding, followed by varying numbers of a C2-set Ig-like domain (9). Most siglecs are expressed on immune cells and possess the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) in their cytoplasmic tails, which is involved in regulation of cellular activation within the immune system (10). There have been several reports showing that siglecs play a role in regulation of TLR4-driven cytokine production. Siglec-9 down-modulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mouse Raw and human THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS (11). We also demonstrated that anti-Siglec-9 antibody treatment reduced the production of IL-12 in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (12). Anti-Siglec-E antibody treatment reduced the production of TNF-α and IL-6 in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages in response to LPS stimulation (13). CD33 (Siglec-3) is a type I glycoprotein with two Ig-like extracellular domains (14, 15). It is the smallest member of the siglec family and is known to recognize both α2-3 and α2-6-linked sialic acids (16, 17). Generally, siglecs are physiologically masked by cell-expressed sialic acids via cis interaction, and siglecs are often relevant to regulation of the function of cis ligands. It is important to identify an endogenous cis ligand for siglecs and investigate whether or not the interaction with the cis ligand is related with the immune regulation. In the present study, we found that TLR4-mediated signaling is down-regulated by anti-CD33 mAb, suggesting that CD33 may be involved in the regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling. Using chemical cross-linking and Duolink techniques, it was demonstrated that CD14 is an endogenous cis ligand for CD33 and that this interaction of CD14 with CD33 regulates the presentation of LPS from CD14 to TLR4. Eventually, CD33 down-modulates the LPS-NF-κB pathway, which is a novel mechanism that regulates TLR4-mediated signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Materials

HEK293T cells, a human embryonic kidney cell line, transfected with TLR4, CD14, and MD-2 cDNAs (TLR cells), were obtained from InvivoGen, and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 4.5 μg/ml d-glucose, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. LPS, zymosan A, and flagellin derived from Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B4, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Salmonella typhimurium, respectively, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pam3CSK4 was from IMGENEX. The cross-linking reagents, bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) and 3,3′-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidylpropionate) (DTSSP), and EZ-Link® Sulfo-NHS-Biotin were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Anti-CD33 mAb was prepared by using recombinant soluble CD33 as an antigen. Recombinant human GM-CSF, IL-4, and CD14 were obtained from PeproTech Inc. Recombinant human CD33-Fc chimera and neuraminidase (Arthrobacter ureafacienes) were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. and Nacalai Tesque Inc., respectively. Rabbit anti-TLR4 Ab were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Rabbit anti-CD14 Ab and mouse anti-CD14 mAb were purchased from Abgent Inc. and EXBIO, respectively.

Generation of TLR Cells Expressing Wild-type, Mutated, and Deleted CD33

Full-length CD33 cDNA (GenBankTM; accession number NM_001772) was generated from total RNA prepared from a human lymphoma cell line, U937 cells, by RT-PCR using the following pair of primers, 5′-GCT TCC TCA GAC ATG CCG C-3′ and 5′-CCA AGA ATC AGC CTT TGG TC-3′. The full-length CD33 cDNA was cloned into the pUC18 vector and amplified by PCR using the above primers. The amplified cDNA was introduced into the pCMV14 vector (Sigma-Aldrich). Mutated CD33 with Ala instead of Arg at residue 119 was generated using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) (18). cDNA coding ITIM-deleted CD33 was prepared by digestion of the CD33 construct with EcoNI, which cleaves the site just before the ITIM-coding region. TLR cells were transfected with pCMV14-CD33, R119A mutated, and ITIM-deleted CD33 cDNA constructs by using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science), and stable transfectants named TLR/CD33WT, TLR/CD33RA, and TLR/CD33DEL cells, respectively, were obtained on G418 selection.

Preparation of Immature Dendritic Cells (imDCs)

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from the buffy coat of a healthy donor by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation. Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells by using MACS human CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Preparation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells was performed according to the method of Chen et al. (19).

Flow Cytometry

Expression of TLR4, CD14, and CD33 was examined by flow cytometry as follows. TLR, TLR/CD33WT, TLR/CD33RA, and TLR/CD33DEL cells were treated with FITC-labeled mouse anti-CD33 mAb (BD Biosciences) or isotype control mouse IgG1 (eBioscience) and with PE-labeled mouse anti-CD14 mAb (BD Biosciences) or isotype control mouse IgG2b (eBioscience) to detect CD33 and CD14, respectively. Expression of TLR4 was analyzed after successive treatment with mouse anti-TLR4 mAb (Imgenex) and FITC-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen). A control experiment was performed using isotype-matched mouse IgG as the primary antibody. The cells were analyzed with a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

ELISA

imDCs induced from monocytes (1.5 × 105 cells) were treated successively with anti-CD33 mAb (1 μg/ml) or mouse isotype IgG and rabbit anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 (0.5 μg/ml) (Millipore) and then cultured in the presence of LPS (1 μg/ml), zymosan A (50 μg/ml), flagellin (0.1 μg/ml), or Pam3CSK4 (0.1 μg/ml) for 20 h. The culture supernatant was collected, and the level of IL-12p70 was determined with ELISA kits (eBioscience).

Binding Assay

Recombinant CD14 (500 ng) was coated onto a Nunc MaxiSorp immunoplate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After blocking of the plate with 3% BSA, it was treated with or without 10 milliunits of neuraminidase (Arthrobacter ureafaciens, Nakalai Tesque) in 50 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37 °C for 20 h. After washing with 0.15 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.2 m NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20, recombinant CD33-Fc was added to the plate. After incubation for 2 h, bound CD33-Fc was detected with HRP-conjugated protein A (Invitrogen). The enzyme reaction was performed with a TMB peroxidase substrate (Nacalai Tesque Inc.), and the absorbance at 450 nm was determined.

Analysis of Interaction between CD33 and CD14 Using Cross-linking Reagent

TLR/CD33WT cells (3 × 106 cells) and imDCs (1 × 107 cells) were treated with 1 mm DTSSP for 1 h at 4 °C. In some cases, the residual primary amino groups were further conjugated with sulfo-NHS-biotin (0.1 mg/ml) for another 1 h at 4 °C. The cells were washed with PBS containing 50 mm glycine and then lysed with cell lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor mixture). Anti-CD33 mAb, anti-CD14 mAb, or mouse isotype IgG1 and protein G-Sepharose were successively added to the cell lysate. The immunoprecipitated CD33 or CD14 and linked proteins, after cleavage of disulfide bonds, were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was treated with mouse anti-CD33 mAb, rabbit anti-TLR4 Ab, or rabbit anti-CD14 Ab overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membrane was treated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Ab or anti-rabbit IgG Ab (Invitrogen), followed by detection with a ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare) and analysis with a Lumino Image Analyzer LAS-4000 plus. When the effect of LPS on co-localization of CD14 with CD33 was examined, TLR/CD33WT cells (3 × 106 cells) were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 10 min, and CD14 cross-linked with CD33 was detected as described above. When BS3 was used, TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA (3 × 106 cells) were treated with 1 mm BS3 for 1 h at 4 °C. The cell lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with rabbit anti-CD14 Ab as described above.

Distribution of CD33 and CD14 on the Surface of imDCs and Detection of Close Proximity of CD33 and CD14

After fixation of imDCs with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde, imDCs were treated with mouse anti-CD33 mAb and rabbit anti-CD14 Ab or mouse IgG1 and rabbit IgG as a control antibody, respectively, at 4 °C for 2 h. After washing with PBS, the cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (Molecular Probes), Alexa Fluor 549-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab (Molecular Probes), and propidium iodide and then observed under a confocal fluorescein microscope (DM5500B, Leica Microsystems).

To visually detect the close proximity of CD33 and CD14 on the cell surface, imDCs seeded on a Lab-Tek II CC2 Chamber SlideTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were stained by using the Duolink in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) system (Olink Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after fixing the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, the imDCs were treated with mouse anti-CD33 mAb and rabbit anti-CD14 Ab as described above. The close proximity of oligonucleotide-ligated secondary antibodies, Duolink PLA probe anti-mouse MINUS and anti-rabbit PLUS, allowed rolling circle amplification. The rolling circle amplification products were hybridized with fluorescently labeled probes, Detection Reagents Orange. The cells were mounted with Duolink II Mounting Medium with DAPI, and then PLA spots representing co-localization of CD33 and CD14 were observed as described above.

Phosphorylation of CD33 and Recruitment of SHP-1 on Ligation of TLR4 with LPS in TLR/CD33WT Cells

TLR/CD33WT cells (1 × 106 cells) were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 0–10 min and then with 0.1 mm pervanadate for 10 min on ice. After washing with PBS, cell lysates were prepared as described above. CD33 was immunoprecipitated with anti-CD33 mAb, and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. CD33, phosphotyrosine, and coimmunoprecipitated SHP-1 on the membrane were detected with anti-CD33 mAb, mouse anti-phosphotyrosine Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and rabbit anti-SHP-1 mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), respectively, and analyzed as described above. The intensities of the bands were determined with ImageJ software.

Estimation of Biotin-labeled LPS Bound to the Cell Surface, TLR4, and CD14 and Internalized by the Cells

TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells (1 × 107 cells) were incubated with 3 μg of biotin-labeled LPS (InvivoGen) at 4 °C for 60 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were lysed, and then biotin-labeled LPS was pulled down from the lysate with streptavidin-Sepharose. The precipitated LPS was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with HRP-streptavidin. Internalized LPS was determined as follows. The three types of cells (1 × 107 cells) as described above were incubated with 3 μg of biotin-labeled LPS at 37 °C for 60 min. To remove cell surface-bound LPS, the cells were incubated with 100 μg of proteinase K in PBS on ice for 30 min, followed by washing and lysis. Internalized LPS was pulled down from the lysate with streptavidin-Sepharose and analyzed as described above.

Biotin-labeled LPS bound to TLR4 and CD14 was determined as follows. The three types of cells (5 × 107 cells) as described above were incubated with 5 μg of biotin-labeled LPS at 4 °C for 60 min and, after washing with cold PBS, further incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing with PBS, cell lysates were prepared, and TLR4 and CD14 were immunoprecipitated as described above. Coimmunoprecipitated LPS was estimated as described above.

Analysis of Signal Transduction

TLR cells (1.5 × 105 cells) were stimulated with various amounts of LPS for 45 min at 37 °C or with LPS (0.01 μg/ml) for various times at 37 °C. TLR/CD33WT, TLR/CD33RA, and TLR/CD33DEL cells were stimulated with LPS (0.01 μg/ml) for 45 min at 37 °C. imDCs (5 × 105 cells) were treated successively with anti-CD33 mAb (1 μg/ml) or mouse isotype IgG (R&D Systems Inc.) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 (0.1 μg/ml) and then cultured in the presence of LPS (0.1 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37 °C. The cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, phosphatase inhibitor, and protease inhibitor mixture). Each cell lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was treated with rabbit anti-phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser-536) mAb or rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology). After washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membrane was treated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen), followed by detection with Chemi-Lumi One L (Nacalai Tesque Inc.) and analysis with a Lumino Image Analyzer LAS-4000 Plus. The intensities of the bands were determined with ImageJ software.

Treatment of Cells with Neuraminidase

TLR/CD33WT cells (1 × 106 cells) were treated with 50 milliunits of neuraminidase (A. ureafaciens, Nacalai Tesque) in serum-free RPMI1640 medium at 37 °C for 1 h.

Statistical Analysis

All discrete values, expressed as mean ± S.D., were analyzed using Student's t test. p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

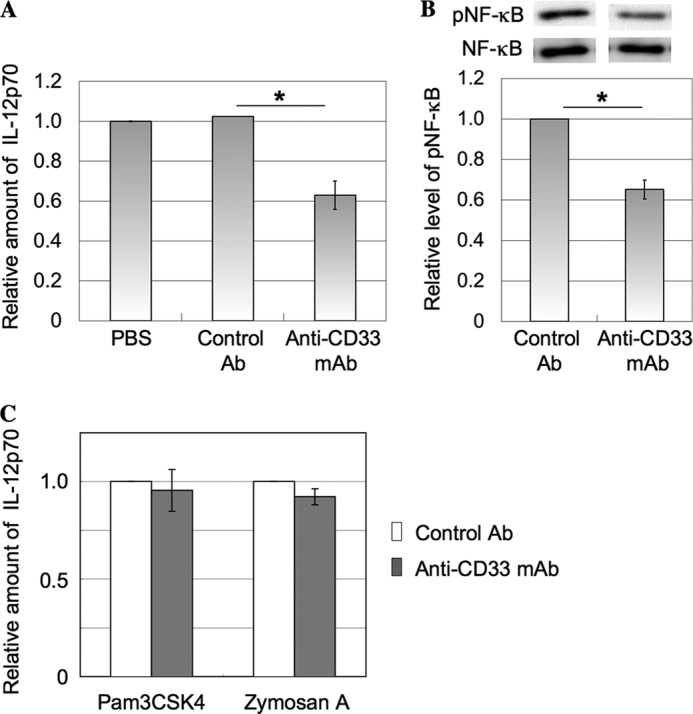

Effects of Anti-CD33 mAb on Production of IL-12 and Phosphorylation of NF-κB in imDCs

imDCs were treated with anti-CD33 mAb and then cultured in the presence of LPS for 20 h as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The level of IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant was determined by ELISA. About 40% of IL-12 production was decreased by the treatment with anti-CD33 mAb (Fig. 1A). To evaluate the effects of anti-CD33 mAb on downstream events, the level of phosphorylated NF-κB was also determined. imDCs were treated similarly for 60 min as described above, and then the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. The level of phosphorylated NF-κB clearly decreased (Fig. 1B), suggesting that CD33 could be involved in negative regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling in the activation pathway. To determine whether or not anti-CD33 mAb also has effects on TLR2/6, TLR1/2, and TLR5-related events, imDCs were stimulated with zymosan A, Pam3CSK4, and flagellin, respectively, in the presence of anti-CD33 mAb or control Ab and cultured for 20 h. The level of IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant was determined by ELISA. Treatment with anti-CD33 mAb had no substantial effect on the production of IL-12 through TLR2/6- and TLR1/2-mediated signaling (Fig. 1C). IL-12 was not detectable in the supernatant of imDCs treated with flagellin. These results suggest that CD33 may be specifically relevant to the regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling. Because many siglecs, including CD33, possess ITIM in their cytoplasmic domains, generally, they down-regulate the signaling through ligation with a receptor carrying a cis ligand. Thus, it is important to find a cis ligand for CD33.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of anti-CD33 mAb on production of IL-12 and phosphorylation of NF-κB in imDCs. A, imDCs induced from monocytes (1.5 × 105 cells) were treated with anti-CD33 mAb as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The culture supernatant was collected, and the level of IL-12p70 was determined with an ELISA kit. The relative amount of IL-12p70 was determined and normalized as to the level detected in the experiment performed with PBS treatment (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3; *, p < 0.05). B, imDCs induced from monocytes (5 × 105 cells) were treated with anti-CD33 mAb as described under “Experimental Procedures” and stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 60 min, and then the cell lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by blotting onto a PVDF membrane. Phosphorylated NF-κB and total NF-κB were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The intensities of the bands were determined with ImageJ software and normalized as to the level detected in the experiment performed using a mouse control isotype Ab (mean ± S.D., n = 3; *, p < 0.05). C, imDCs induced from monocytes (1.5 × 105 cells) were stimulated with zymosan A and Pam3CSK4 in the presence of anti-CD33 mAb or control Ab and cultured for 20 h as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The culture supernatant was collected, and the level of IL-12 was determined with an ELISA kit. The relative amount of IL-12 was determined and normalized as to the level detected in the experiment performed in the presence of control Ab (mean ± S.D., n = 3).

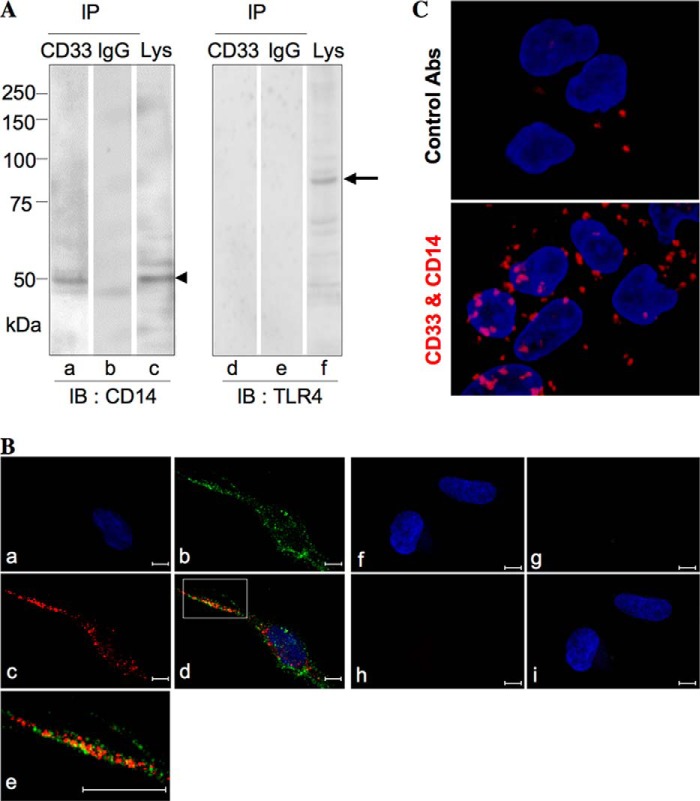

Detection of an Endogenous cis Ligand for CD33 and Distribution of CD33 and CD14 on the Surface of imDCs

To detect a cis ligand present in close proximity to CD33, the cell surface proteins of imDCs were cross-linked chemically with DTSSP as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The LPS receptor complex consists of at least three proteins, CD14, TLR4, and MD-2. They are all glycoproteins and have four, nine, and two N-glycosylation sites, respectively (20). Thus, there is a possibility that CD33 may bind to these molecules. The immunoprecipitates prepared from the lysate with anti-CD33 mAb and a part of the lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, followed by Western blotting and detection with antibodies against membrane proteins of the LPS receptor complex. Interestingly, a band corresponding to CD14 but not that corresponding to TLR4 was detected in the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb (Fig. 2A, lanes a and d), suggesting the co-localization of CD14 with CD33. Thus, we observed immunochemically the distribution of CD33 and CD14 on the surface of imDCs. The distribution of CD14 and CD33 was not uniform but was patchy on the cell surface. A small part of CD14 molecules seemed to be co-localized with CD33 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, putative interaction of the molecules stained with a pair of anti-CD14 and anti-CD33 mAbs was assessed using Duolink technology as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A significant number of spots were observed on the surface of imDCs compared with a control experiment (Fig. 2C), this being indicative of their molecular proximity. In addition, to estimate CD14 molecules co-localized with CD33, the intensities of the bands of CD14 cross-linked with CD33 (Fig. 2A, lane a) and contained in the cell lysates (Fig. 2A, lane c) on the blotted membrane were determined, and the values were converted into those in the total cell lysates. CD14 cross-linked with CD33 was estimated to comprise ∼2% of total CD14 molecules. Whether or not this level of CD14 molecules co-localized with CD33 has some effect on TLR4-mediated signaling is discussed below. To further examine the interaction of CD33 and CD14, CD33 cDNA was introduced into TLR4-, CD14-, and MD-2-expressing HEK293T cells (TLR cells), and stable transfectants (TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA cells) were established as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of CD33 and CD14 and their close proximity on the surface of imDCs. A, imDCs induced from monocytes (1 × 107 cells) were treated with 1 mm DTSSP for 1 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitate (IP) prepared from the cell lysate with mouse anti-CD33 mAb or control isotype IgG and a part of the lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, followed by Western blotting (IB) and detection with rabbit anti-CD14 Ab or rabbit anti-TLR4 Ab. Arrowhead and arrow, CD14 and TLR4, respectively. B, imDCs induced from monocytes (1.5 × 105 cells) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. The distribution of CD33 and CD14 was examined using the combinations of mouse anti-CD33 mAb and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (b) and rabbit anti-CD14 Ab and Alexa Fluor 549-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab (c), respectively, merged images being shown in d. The area outlined by a square in d was magnified, as shown in e. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (a and f). Control experiments were performed using Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (g) and Alexa Fluor 549-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab (h) without primary antibodies, merged images being shown in i. The cells were observed under a confocal microscope (bar, 10 μm). C, imDCs induced from monocytes (4 × 104 cells) were treated as described above. The putative interaction of CD33 and CD14 stained with a pair of antibodies was assessed using Duolink technology as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Red spots indicate molecular proximity and are indicative of molecular interactions. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were observed under a confocal microscope.

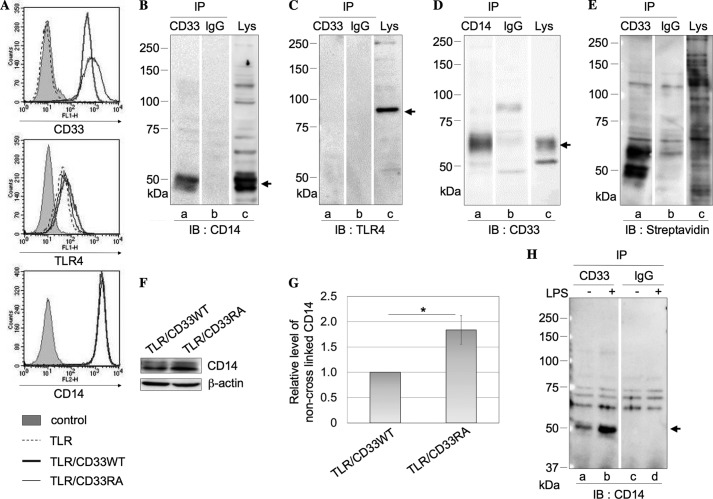

Expression of TLR4, CD14, and CD33 was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). TLR/CD33WT cells were treated similarly with DTSSP, and the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb was prepared from the cell lysate as described above. A band corresponding to CD14 was detected in both the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb (Fig. 3B, lane a) and the lysate (Fig. 3B, lane c), whereas TLR4 was not detected in the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb (Fig. 3C, lane a). In a reciprocal experiment, CD33 was detected in the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD14 mAb (Fig. 3D, lane a). Furthermore, we examined cell surface proteins cross-linked with CD33. After cross-linking, the cell surface proteins were successively treated with sulfo-NHS-biotin, and the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb was subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, followed by Western blotting and detection with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. As shown in Fig. 3E (lane a), the major cross-linked proteins were CD14 and CD33 itself. In addition, a band corresponding to MD-2 (∼25 kDa) was not detected for the immunoprecipitate with anti-CD33 mAb (Fig. 3E, lane a). These results indicate that CD33 is present in close proximity to CD14 and is almost exclusively associated with CD14 except for CD33 itself. We also performed a similar experiment using TLR/CD33RA cells. However, quantitative data were not obtained, probably due to the different reactivities of anti-CD33 mAb to wild-type and mutated CD33 on the blotted membrane (data not shown). Thus, we performed a similar experiment to examine the close association of CD33 with CD14 using a different cross-linker, BS3, which does not include a disulfide bond, unlike DTSSP. After treatment of TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA cells with BS3 as described under “Experimental Procedures,” the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with anti-CD14 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, F and G, a higher level of non-cross-linked CD14 with a molecular mass of about 50 kDa was detected in TLR/CD33RA cells compared with that in TLR/CD33WT cells, suggesting that the Arg residue of CD33 is relevant to the close association with CD14. In addition, to examine whether or not stimulation by LPS has an effect on the co-localization of CD14 with CD33, TLR/CD33WT cells were incubated in the presence or absence of LPS at 37 °C for 10 min, and the same experiment as described above was performed (Fig. 3H). It should be noted that CD14 cross-linked with CD33 significantly increased (about 3-fold) with the stimulation by LPS, suggesting that CD33 may be closely associated with CD14 in the process of signaling (Fig. 3H, lanes a and b). Even if only a small part of CD14 molecules is co-localized with CD33, close association of CD14 with CD33 may play a critical role in the regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling. This finding is interesting, and the details are currently under investigation.

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of cell surface proteins cross-linked with CD33. A, expression of CD33, TLR4, and CD14 was confirmed in TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA cells by flow cytometry. B, using TLR/CD33WT cells (3 × 106 cells), the same procedure as in Fig. 2A was performed. After Western blotting, CD14 was detected with anti-CD14 Ab. Arrow, CD14. C, the same procedure was performed as in B, and after Western blotting, TLR4 was detected. Arrow, TLR4. D, from the cell lysate treated as described in B, the immunoprecipitate obtained with anti-CD14 Ab or control isotype IgG and a part of the lysate were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with anti-CD33 mAb. Arrow, CD33. E, after treatment of TLR/CD33WT cells with 1 mm DTSSP and then with sulfo-NHS-biotin (0.1 mg/ml), the same procedure as in Fig. 2B was performed, and biotin-labeled proteins were detected with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. F, TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA cells (3 × 106 cells) were treated with 1 mm BS3 at 4°C for 1 h. The cell lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with rabbit anti-CD14 Ab. G, the histograms show the relative intensities of CD14 in F. The value for the experiment performed using TLR/CD33WT cells was taken as 1 (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3; *, p < 0.05). H, TLR/CD33WT cells (3 × 106 cells) were treated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 10 min, and CD14 cross-linked with CD33 was detected as described above. Arrow, CD14. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting.

It is well known that imDCs express various siglecs, including CD33. The interaction of CD14 with other siglecs, such as Siglec-5, -7, and -9, was also examined using a cross-linker, DTSSP, as described above. No siglecs other than CD33 could be cross-linked with CD14 (data not shown). Thus, it seems unlikely that CD33 was recovered incidentally in detergent micelles, including CD14.

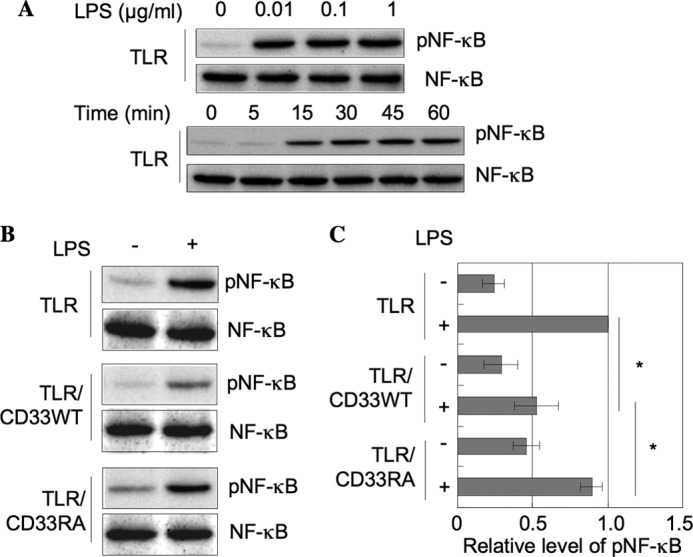

Effect of CD33 on TLR4-mediated NF-κB Phosphorylation

The phosphorylation of NF-κB, which is a downstream event in TLR4-mediated signaling, was evaluated in TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells after stimulation with LPS. TLR cells were stimulated with various amounts of LPS for 45 min, and then the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. NF-κB was phosphorylated with a low amount of LPS (0.01 μg/ml) in TLR cells, and the phosphorylation reached the maximum level at 30 min after treatment (Fig. 4A). TLR/CD33WT and TLR/CD33RA cells were stimulated with LPS (0.01 μg/ml) for 45 min, and phosphorylated NF-κB was detected as described above. As shown in Fig. 4, B and C, the phosphorylation of NF-κB was clearly down-modulated in TLR/CD33WT cells, whereas the down-modulating activity toward TLR4-mediated signaling was decreased by mutation of the sialic acid-binding site. The level of NF-κB phosphorylation in TLR/CD33RA cells corresponded to that in TLR cells. These results indicate that sialic acid-binding activity is essential for negative regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of TLR4-mediated NF-κB phosphorylation due to sialic acid-binding activity of CD33. A, TLR cells (1.5 × 105 cells) were stimulated with various amounts of LPS for various times, and then the level of NF-κB phosphorylation was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. B, TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells (1.5 × 105 cells) were treated with LPS (0.01 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 45 min, and then NF-κB was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. C, the data in B were analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1B and normalized as to the level in the experiment using TLR cells stimulated with LPS (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3; *, p < 0.05).

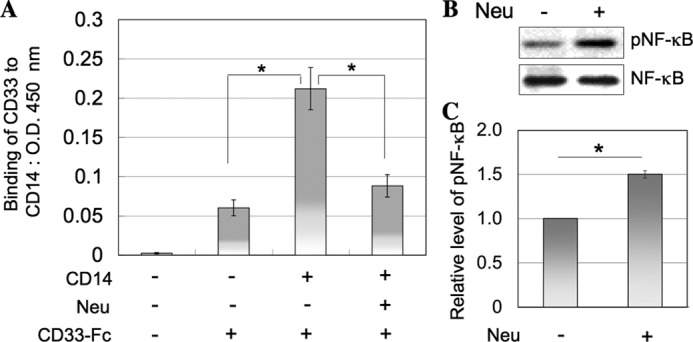

Interaction of CD14 with CD33

To confirm the interaction of CD14 with CD33, a plate assay was performed. Recombinant CD14 was coated onto a plate, and then the binding of recombinant soluble CD33 was determined before or after treatment of the CD14-coated plate with neuraminidase. We confirmed that immobilized CD14 was hardly detached from the well by the neuraminidase treatment (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5A, CD33 bound to CD14 and neuraminidase treatment abolished the binding activity, indicating that CD33 bound to CD14 through its sialylated carbohydrate chain. These results suggest that CD33 is not incidentally co-localized with CD14 but ligated with the sialylated carbohydrate chain of CD14. To further demonstrate that sialic acid residues are relevant to the regulation of TLR4- mediated signaling, the phosphorylation of NF-κB in TLR/CD33WT cells treated with or without neuraminidase was examined after stimulation with LPS. TLR/CD33WT cells were treated with neuraminidase, and the partial removal of sialic acid residues from the cell surface was confirmed by the decreased binding of sialic acid-binding lectins to the cell surface (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, B and C, the level of phosphorylated NF-κB was elevated by the treatment with neuraminidase, this being consistent with the fact that sialic acid residues are relevant to the regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling. As described above, imDCs express some siglecs, including CD33. These CD33-related siglecs exhibit similar sugar-binding specificities. The reason why CD33 selectively cross-linked with CD14 is unclear at present. We speculate that the sialic acid-binding domain of CD33 may be spatially fitted to the sites of sialic acid residues borne on CD14. CD33 is the smallest member of the siglec family and possesses two Ig-like extracellular domains, the other CD33-related siglecs such as Siglec-5, -7, and -9 having more than three Ig-like extracellular domains.

FIGURE 5.

Interaction of CD33 with CD14 and effect of neuraminidase treatment on NF-κB phosphorylation in TLR/CD33WT cells stimulated with LPS. A, CD14-coated or non-coated plate was treated with or without neuraminidase, and then the binding of soluble recombinant CD33 was determined (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3; *, p < 0.05). B, TLR/CD33WT cells (1 × 106 cells) treated with or without neuraminidase as described under “Experimental Procedures” were stimulated with LPS, and then the phosphorylation of NF-κB was examined as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. C, the histograms show the relative intensities of phosphorylated NF-κB in B. The value for the experiment performed using TLR/CD33WT cells treated without neuraminidase was taken as 1 (mean ± S.D., n = 3; *, p < 0.05).

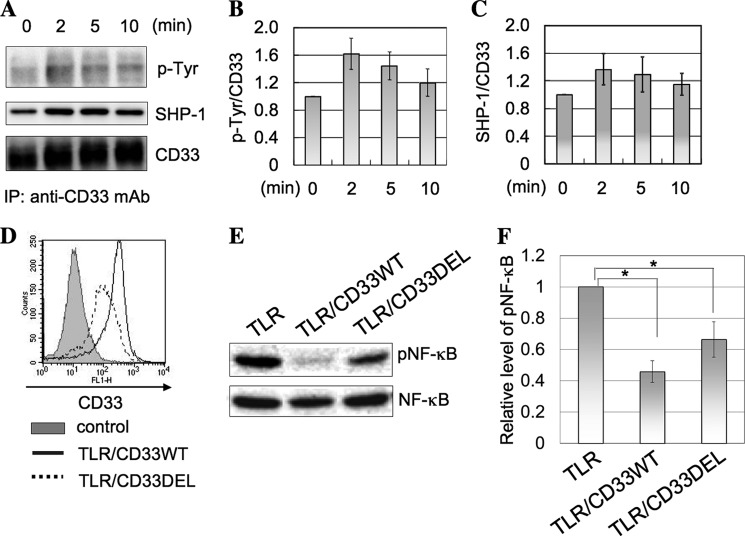

Analyses of CD33-ITIM-related Events on Ligation of TLR4 with LPS

Because it has been reported that, upon stimulation with LPS, the redistribution of TLR4 to the lipid rafts occurs (21), we speculated that there might be a similar relationship between TLR4 and siglecs to that between CD22 and the B cell receptor. It is generally agreed that when the B cell receptor is ligated with an antigen, the B cell receptor and CD22 are translocated to lipid rafts, phosphorylation is catalyzed by Lyn localized in the lipid rafts, and SHP-1/2 is recruited to the phosphorylated ITIM of CD22, leading to negative regulation of B cell receptor-mediated signaling (22). Thus, we examined the phosphorylation of CD33 and recruitment of SHP-1 to CD33 following ligation of LPS in TLR/CD33WT cells. TLR/CD33WT cells were stimulated with LPS, and the immunoprecipitates prepared from the cell lysates with anti-CD33 mAb were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. Phosphorylation of CD33 and subsequent recruitment of SHP-1 were slightly elevated in TLR/CD33 cells in response to LPS (Fig. 6, A–C), but these results were not statistically significant. To examine further whether or not the ITIM of CD33 is related with the down-modulation of TLR4-mediated signaling, we also prepared cells expressing ITIM-deleted CD33 (TLR/CD33DEL) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” TLR/CD33DEL cells were stimulated with LPS, and then the level of phosphorylated NF-κB was compared with that in TLR and TLR/CD33WT cells. Expression of CD33 on the surface of TLR/CD33DEL cells was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 6D). Although the level of phosphorylated NF-κB in TLR/CD33DEL cells was higher than that in TLR-4/CD33WT cells, it was moderately inhibited, this being consistent with the finding that the carbohydrate-binding domain of CD33 plays an important role in the regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling (Fig. 6, E and F). These results suggest that ITIM-related events of CD33 may have little effect, if any, on the TLR4-mediated signaling. Next, we speculated about the possibility that the interaction of CD33 with CD14 may affect the binding and/or uptake of LPS.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of CD33-ITIM-related events on ligation of TLR4 with LPS. A, TLR/CD33WT cells (1 × 106 cells) were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 0–10 min. CD33 was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. CD33, phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), and SHP-1 were detected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B and C, the intensities of the bands in A were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The histograms show the relative intensities of phospho-Tyr/CD33 (B) and SHP-1/CD33 (C). The value for the experiment performed without LPS stimulation (0 min) was taken as 1. D, expression of CD33 in TLR/CD33DEL cells was analyzed by flow cytometry as described under “Experimental Procedures.” E, TLR4-mediated NF-κB phosphorylation was determined in TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33DEL cells as described in Fig. 1B. F, the histograms show the relative intensities of phosphorylated NF-κB in E. The value for the experiment performed using TLR cells was taken as 1 (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3; *, p < 0.05).

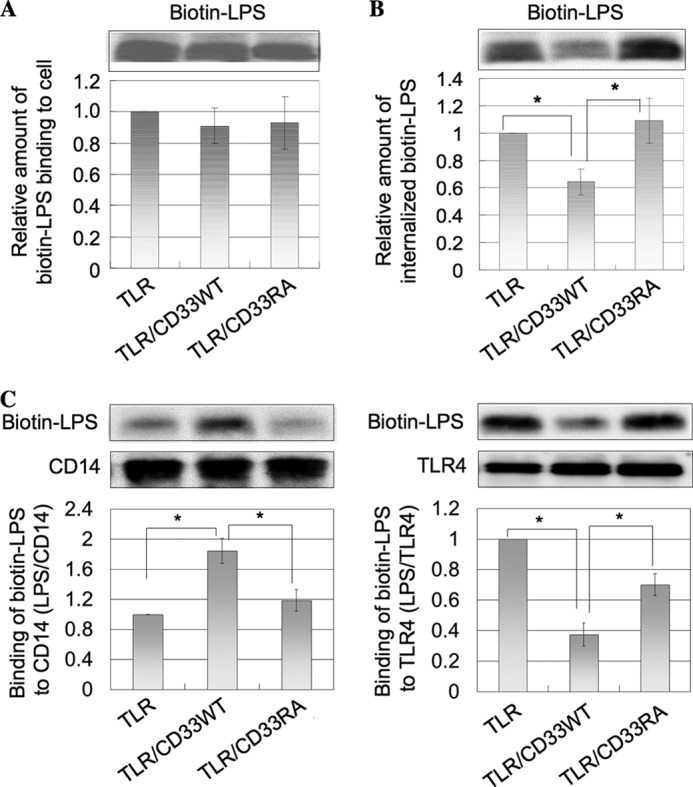

Effect of CD33 on Binding of LPS to CD14 and TLR4

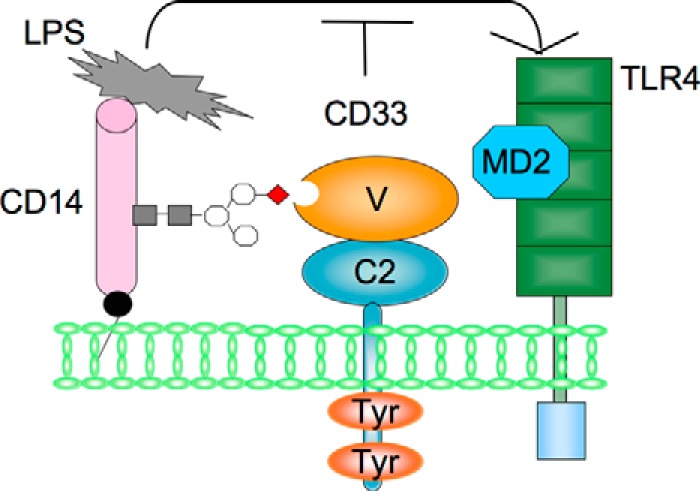

CD14 has been found to be the major receptor for LPS (23, 24). Binding of LPS to the surface of TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells was examined using fluorescence-labeled LPS by flow cytometry. The level of bound LPS did not change irrespective of the expression of either the wild-type or mutated CD33 (data not shown). Furthermore, binding of biotin-labeled LPS to the cell surface and its uptake into the cell were compared among these cells. First, TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells were incubated with biotin-labeled LPS at 4 °C for 60 min. After extensive washing with cold PBS, the cells were lysed. LPS was pulled down with streptavidin-Sepharose from the lysate and then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with HRP-streptavidin. Similar levels of LPS bound to the three types of cells (Fig. 7A), this being consistent with the results of flow cytometry as described above. Next, these cells were incubated with biotin-labeled LPS at 37 °C for 60 min and then treated with protease K to remove LPS bound to the cell surface proteins. Intracellular LPS was determined as described above. The uptake of LPS was significantly decreased in TLR/CD33WT cells compared within TLR and TLR/CD33RA cells (Fig. 7B). With respect to the function of CD14, Zanoni et al. (25) demonstrated that CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of TLR4. During the process of the internalization of LPS, CD14 is known to chaperone LPS to the TLR4·MD-2 signaling complex (5, 26, 27). Next, we examined the possibility that the presentation of LPS by CD14 may be affected by the interaction of CD14 with CD33. Thus, these cells were treated with LPS at 4 °C for 60 min and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. From the cell lysates, CD14 and TLR4 were immunoprecipitated. LPS coimmunoprecipitated with CD14 or TLR4 was detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. An about 1.8-fold amount of LPS was associated with CD14 in TLR/CD33WT cells compared with in TLR cells, whereas the level of CD14-bound LPS in TLR/CD33RA cells was similar to that in TLR cells. In contrast, a significantly lower level of TLR4-bound LPS was detected in TLR/CD33WT cells compared with in TLR cells (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that the interaction of CD14 with CD33 may regulate the presentation of LPS from CD14 to TLR4. As described above, B cell receptor-mediated signaling is down-regulated by directly associated CD22 (28). In contrast, it was CD14 but not TLR4 that was directly associated with CD33 in imDCs, unlike the relation between the B cell receptor and CD22, suggesting a different inhibitory mechanism. It has been reported that danger-associated molecular patterns, which are intracellular components, such as HMGB1 (high mobility group box 1), induce TLR-dependent inflammatory responses (29, 30). Recently, Chen et al. (31) demonstrated that CD24, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein like CD14, was identified as a receptor for HMGB1 and that Siglec-10 bound to CD24. Siglec-10 down-modulated NF-κB activation triggered by ligation with HMGB1 (31). Although the precise role of Siglec-10 in the down-regulation of the signaling has not been elucidated yet, a similar type of complex, CD14/CD33 and CD24/Siglec-10, may play an important role in the down-regulation of TLR-mediated signaling after ligation with LPS and HMGB1, respectively. Taken together, we postulate a novel model for regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling (Fig. 8), in which CD33 plays an essential role through its direct association with CD14 but not with TLR4. In this context, sialylation or desialylation on the cell surface glycoconjugates could potentially regulate the functional glycoprotein receptors. With respect to carbohydrate moieties expressed in DCs, Bax et al. (32) reported that the expression of sialic acid is up-regulated during maturation, this being correlated with the increased binding of some siglecs. This change may facilitate the binding of CD33 to CD14, thereby leading to stronger down-modulation of TLR4-mediated signaling in mature DCs. On the other hand, endogenous sialidase activity increases in cells of the immune system during cell activation or differentiation. Stamatos et al. (33) reported that removal of sialic acid from glycoconjugates on the surface of monocytes enhances their response to LPS, which is consistent with our present results.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of LPS presentation from CD14 to TLR4 by CD33. A, TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells (1 × 107 cells) were incubated with 3 μg of biotin-labeled LPS at 4 °C for 60 min. After washing, biotin-labeled LPS bound on the cell surface was precipitated from cell lysates with streptavidin-Sepharose and then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting and detection with HRP-streptavidin. The intensities of the bands were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1B and normalized as to the level detected in the experiment performed using TLR cells (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3). B, TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells (1 × 107 cells) were incubated with 3 μg of biotin-labeled LPS at 37 °C for 60 min. After washing, the cells were treated with 100 μg of proteinase K on ice for 30 min. Internalized LPS was obtained and analyzed as described in A. The intensities of the bands were determined and normalized as to the level detected in the experiment performed using TLR cells as in A (mean ± S.D., n = 3; *, p < 0.05). C, TLR, TLR/CD33WT, and TLR/CD33RA cells (5 × 107 cells) were incubated with 5 μg of biotin-labeled LPS at 4 °C for 60 min. After washing and subsequent incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the cells were lysed, and CD14 and TLR4 were immunoprecipitated prepared from the cell lysates. The precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and coimmunoprecipitated biotin-labeled LPS was detected as described in A. The relative intensities of the bands (LPS/CD14 and LPS/TLR4) were determined and were normalized as to the level obtained in the experiment performed using TLR cells (mean ± S.D., n = 3; *, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 8.

A novel model of negative regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling by CD33. We postulate a novel model in which CD33 plays a role in negative regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling. CD33 binds to the sialylated carbohydrate chain of CD14 on the surface of imDCs. CD33 may be present with CD14 in an LPS receptor complex and give rise to negative regulation of TLR4-mediated signaling, probably by regulating the presenting process of LPS from CD14 to TLR4.

This work was supported by a Private University Strategic Research Foundation Support Program.

- DC

- dendritic cell

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- imDC

- immature dendritic cell

- ITIM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif

- Ab

- antibody

- BS3

- bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate

- DTSSP

- 3,3′-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidylpropionate)

- PLA

- Duolink in situ proximity ligation assay

- TMB

- tetramethyl benzidine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gay N. J., Keith F. J. (1991) Drosophila Toll and IL-1 receptor. Nature 351, 355–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. (2006) Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ulevitch R. J., Tobias P. S. (1995) Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13, 437–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jiang Q., Akashi S., Miyake K., Petty H. R. (2000) Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF-κB. J. Immunol. 165, 3541–3544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. da Silva Correia J., Soldau K., Christen U., Tobias P. S., Ulevitch R. J. (2001) Lipopolysaccharide is in close proximity to each of the proteins in its membrane receptor complex: transfer from CD14 to TLR4 and MD-2. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21129–21135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mackman N., Brand K., Edgington T. S. (1991) Lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the human tissue factor gene in THP-1 monocytic cells requires both activator protein 1 and nuclear factor κB binding sites. J. Exp. Med. 174, 1517–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller S. I., Ernst R. K., Bader M. W. (2005) LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liew F. Y., Xu D., Brint E. K., O'Neill L. A. (2005) Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 446–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crocker P. R., Paulson J. C., Varki A. (2007) Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ravetch J. V., Lanier L. L. (2000) Immune inhibitory receptors. Science 290, 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ando M., Tu W., Nishijima K., Iijima S. (2008) Siglec-9 enhances IL-10 production in macrophages via tyrosine-based motifs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369, 878–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohta M., Ishida A., Toda M., Akita K., Inoue M., Yamashita K., Watanabe M., Murata T., Usui T., Nakada H. (2010) Immunomodulation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells through ligation of tumor-produced mucins to Siglec-9. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 402, 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boyd C. R., Orr S. J., Spence S., Burrows J. F., Elliott J., Carroll H. P., Brennan K., Ní Gabhann J., Coulter W. A., Jones C., Crocker P. R., Johnston J. A., Jefferies C. A. (2009) Siglec-E is up-regulated and phosphorylated following lipopolysaccharide stimulation in order to limit TLR-driven cytokine production. J. Immunol. 183, 7703–7709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simmons D., Seed B. (1988) Isolation of a cDNA encoding CD33, a differentiation antigen of myeloid progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 141, 2797–2800 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tchilian E. Z., Beverley P. C., Young B. D., Watt S. M. (1994) Molecular cloning of two isoforms of the murine homolog of the myeloid CD33 antigen. Blood 83, 3188–3198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brinkman-Van der Linden E. C., Varki A. (2000) New aspects of siglec binding specificities, including the significance of fucosylation and of the sialyl-Tn epitope. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin superfamily lectins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8625–8632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freeman S. D., Kelm S., Barber E. K., Crocker P. R. (1995) Characterization of CD33 as a new member of the sialoadhesin family of cellular interaction molecules. Blood 85, 2005–2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varki A., Angata T. (2006) Siglecs: the major subfamily of I-type lectins. Glycobiology 16, 1R–27R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen X., Doffek K., Sugg S. L., Shilyansky J. (2004) Phosphatidylserine regulates the maturation of human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 173, 2985–2994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrero E., Hsieh C. L., Francke U., Goyert S. M. (1990) CD14 is a member of the family of leucine-rich proteins and is encoded by a gene syntenic with multiple receptor genes. J. Immunol. 145, 331–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Triantafilou M., Morath S., Mackie A., Hartung T., Triantafilou K. (2004) Lateral diffusion of Toll-like receptors reveals that they are transiently confined within lipid rafts on the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 117, 4007–4014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pierce S. K. (2002) Lipid rafts and B-cell activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wright S. D., Ramos R. A., Tobias P. S., Ulevitch R. J., Mathison J. C. (1990) CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 249, 1431–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hailman E., Lichenstein H. S., Wurfel M. M., Miller D. S., Johnson D. A., Kelley M., Busse L. A., Zukowski M. M., Wright S. D. (1994) Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein accelerates the binding of LPS to CD14. J. Exp. Med. 179, 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zanoni I., Ostuni R., Marek L. R., Barresi S., Barbalat R., Barton G. M., Granucci F., Kagan J. C. (2011) CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4. Cell 147, 868–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gioannini T. L., Teghanemt A., Zhang D., Coussens N. P., Dockstader W., Ramaswamy S., Weiss J. P. (2004) Isolation of an endotoxin-MD-2 complex that produces Toll-like receptor 4-dependent cell activation at picomolar concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4186–4191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moore K. J., Andersson L. P., Ingalls R. R., Monks B. G., Li R., Arnaout M. A., Golenbock D. T., Freeman M. W. (2000) Divergent response to LPS and bacteria in CD14-deficient murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 165, 4272–4280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tedder T. F., Tuscano J., Sato S., Kehrl J. H. (1997) CD22, a B lymphocyte-specific adhesion molecule that regulates antigen receptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 481–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cavassani K. A., Ishii M., Wen H., Schaller M. A., Lincoln P. M., Lukacs N. W., Hogaboam C. M., Kunkel S. L. (2008) TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2609–2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tian J., Avalos A. M., Mao S. Y., Chen B., Senthil K., Wu H., Parroche P., Drabic S., Golenbock D., Sirois C., Hua J., An L. L., Audoly L., La Rosa G., Bierhaus A., Naworth P., Marshak-Rothstein A., Crow M. K., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Kiener P. A., Coyle A. J. (2007) Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat. Immunol. 8, 487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen G. Y., Tang J., Zheng P., Liu Y. (2009) CD24 and Siglec-10 selectively repress tissue damage-induced immune responses. Science 323, 1722–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bax M., García-Vallejo J. J., Jang-Lee J., North S. J., Gilmartin T. J., Hernández G., Crocker P. R., Leffler H., Head S. R., Haslam S. M., Dell A., van Kooyk Y. (2007) Dendritic cell maturation results in pronounced changes in glycan expression affecting recognition by siglecs and galectins. J. Immunol. 179, 8216–8224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stamatos N. M., Carubelli I., van de Vlekkert D., Bonten E. J., Papini N., Feng C., Venerando B., d'Azzo A., Cross A. S., Wang L. X., Gomatos P. J. (2010) LPS-induced cytokine production in human dendritic cells is regulated by sialidase activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 1227–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]