Abstract

We studied the effects of recombinant human growth hormone (r-hGH) on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by growing both wild-type and drug-resistant variants of virus in the presence of various concentrations of eight different antiretroviral drugs. r-hGH had no significant effect on either viral replication or the 50% inhibitory concentrations of these compounds.

Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has led to declines in the rates of mortality and AIDS-related opportunistic infections in the developed world, there remains a need to prevent the loss of lean body tissue (wasting) in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS (12, 16). Human growth hormone (hGH) increases lean body mass and muscle nitrogen retention and thus represents a potential approach to the treatment of AIDS-related wasting (9, 13). In randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials performed in the pre-HAART and HAART eras, recombinant hGH (r-hGH) was shown to increase total body weight and lean body mass and to decrease body fat content (9, 15, 17, 20). These changes are associated with improvements in physical performance and quality of life (15, 17, 20). Although optimization of nutritional status and exercise may also provide benefits in many cases, treatment with hGH is an excellent option in patients with severe wasting.

However, concern exists that r-hGH might stimulate viral replication or inhibit the activities of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) (4), since one early study actually found that r-hGH increased the levels of p24 antigen released from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in tissue culture at concentrations of 50 or 100 ng/ml, but not at concentrations of 1, 5, 10, or 250 ng/ml (7). Importantly, r-hGH did not affect the antiviral activity of zidovudine in that study. Subsequent experiments (E. Daar, unpublished data) showed that r-hGH did not increase the level of HIV replication in PBMCs at concentrations of up to 250 ng/ml and had no effect on the antiviral activities of a variety of ARVs used in the pre-HAART era (zidovudine, didanosine, zalcitabine, and stavudine). The present experiments confirm and extend these findings through the use of currently approved ARVs in each of the three major drug classes.

Drugs.

r-hGH (Serostim), obtained from Serono Inc. (Rockland, Mass.), was reconstituted in an accompanying vial of sterile water (for injection, USP; provided by the company) and further diluted to final concentrations of 10 and 50 ng/ml in tissue culture medium. Tenofovir was provided by Gilead Sciences (Foster City, Calif.). Abacavir and amprenavir were provided by GlaxoSmithKline Inc. (Research Triangle Park, N.C.), and delavirdine and nelfinavir were provided by Agouron Inc. (San Diego, Calif.). Efavirenz, nevirapine, and lopinavir were obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb Inc. (Wallingford, Conn.), Boehringer-Ingelheim Inc. (Ridgefield, Conn.), and Abbott Laboratories Inc. (North Chicago, Ill.), respectively.

Viral isolates.

We used two wild-type (wt) and five drug-resistant clinical isolates of HIV type 1 (HIV-1), the genotypes of which are shown in Table 1. The wt isolates were from patients who had not received therapy. The concentrations of all approved ARVs that inhibit viral replication by 50% (IC50s) for the isolates were confirmed to be the same as those for other wt isolates, and the phenotypes of the isolates were the same as those of other wt isolates. Genotyping for the detection of mutations associated with drug resistance was performed by sequencing analysis with the Tru-Gene system (Bayer Diagnostics Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The resistant isolates were from patients who had been extensively treated with antiviral agents.

TABLE 1.

Effects of r-hGH at 10 or 50 ng/ml on levels of p24 antigen in PBMC culture fluids

| Viral strain | Genotype | Phenotype | p24 conc (ng/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | r-hGH, 10 ng/ml | r-hGH, 50 ng/ml | |||

| 1 | wt | wt | 47.5 ± 3.8 | 41.9 ± 4.2 | 50.7 ± 5.1 |

| 2 | wt | wt | 189.0 ± 14.3 | 150.0 ± 10.1 | 168.9 ± 3.1 |

| 3 | (K103N, Y181Y/C) (M46I, V82T, 184V, 90M)b | Resistant | 93.6 ± 3.1 | 79.2 ± 3.6 | 85.0 ± 5.1 |

| 4 | (M184V) (V77I, L63P, I93L) | Resistant | 203.0 ± 5.4 | 201.5 ± 5.8 | 191.0 ± 5.3 |

| 5 | (K103N, Y181C) | Resistant | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 10.9 ± 0.7 | 13.4 ± 0.9 |

| 6 | (M41L, T69D, K70R, L74V, K103N, Y181C, M184V, H208Y) (M46I/L, 184V, L90M) | Resistant | 189.0 ± 14.3 | 150.0 ± 10.1 | 168.9 ± 12.1 |

| 7 | (T69D, V118I, M184V, T215F) (L63P) | Resistant | 134.9 ± 3.9 | 130.7 ± 3.8 | 128.4 ± 5.8 |

The results are presented as means ± standard deviations. Each experiment was performed with three replicate samples and was repeated on at least two different occasions.

Mutations in the first set of parentheses represent drug resistance-associated substitutions in the RT gene, while those in the second set of parentheses represent changes in the viral protease gene.

In vitro studies.

IC50s were determined by growing wt or drug-resistant variants of HIV in cultured PBMCs in the presence of various concentrations of the different ARVs, ranging from 0.001 to 10 μM, as described previously (3, 18). Viral p24 concentrations in culture fluids were measured (Abbott Laboratories Inc., North Chicago, Ill.) to generate IC50s (8). The effects of r-hGH on viral replication and antiretroviral activity were assessed by adding the hormone to cultures at a concentration of 10 or 50 ng/ml; these represent the midrange and maximum concentrations, respectively, expected in plasma after subcutaneous injection of a standard daily dose of 6 mg of r-hGH. To generate viral stocks, patient PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Viral replication was enhanced by coculture of HIV-infected PBMCs with phytohemagglutinin-stimulated donor PBMCs in complete medium containing interleukin-2, followed by serial passage with fresh uninfected cells to generate further rounds of replication. Viral production during each passage was monitored by measurement of reverse transcriptase (RT) activity and p24 antigen levels. Amplified viral stocks were assayed for p24 antigen, RT activity, and infectivity. Infectivity was assessed by determining the 50% tissue culture infective dose in PBMCs. Viral stocks were stored at −135°C until they were required.

For each concentration of virus, ARV, and r-hGH, inhibitory activity against HIV was calculated as the amount p24 obtained with an antiretroviral concentration of x/amount of p24 obtained with an antiretroviral concentration of 0. The logarithm of (1 − activity)/activity was regressed on the logarithm of the concentration of the antiretroviral agent by least-squares linear regression to predict the IC50 of each antiretroviral agent (1). IC50s obtained in the presence and the absence of r-hGH were compared by two-way analysis of variance.

Effects of r-hGH on cell replication in vitro.

Preliminary experiments first confirmed that r-hGH had no significant effect on cell replication kinetics. After 7 days, the mean number of cells in cultures originally seeded at 2 × 106 cells/ml was 7.4 × 106/ml in the absence of r-hGH, whereas the mean numbers of cells were 8.0 × 106 and 8.5 × 106/ml in the presence of r-hGH at 10 and 50 ng/ml, respectively.

Effects of r-hGH on HIV-1 replication and antiretroviral activity in vitro.

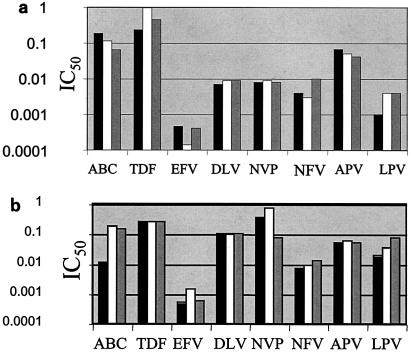

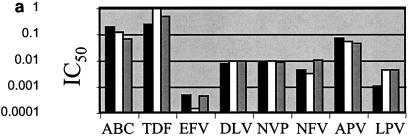

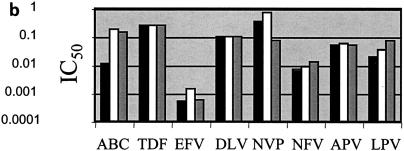

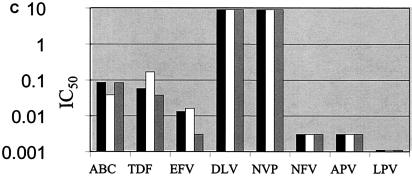

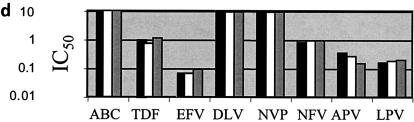

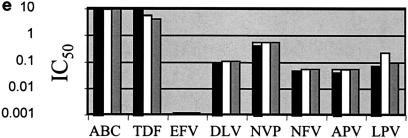

p24 antigen concentrations were measured after infection of PBMCs over 7 days with the seven HIV isolates used in these studies in the presence or absence of r-hGH. The results in Table 1 show that r-hGH had no significant effect on the replication of any of the HIV variants studied. Moreover, the presence of r-hGH at either 10 or 50 ng/ml had no significant effect on the IC50s of any of the eight ARVs tested for the two wt isolates (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows a similar lack of an effect of r-hGH when the five drug-resistant variants of HIV-1 were studied.

FIG. 1.

IC50s of eight ARVs for two wt clinical HIV-1 isolates (a and b) in the presence and absence of r-hGH (logarithmic scale). Each experiment was performed by using three replicate samples and was repeated on at least two different occasions. In no instance were significant differences in IC50s observed between studies performed in the presence or absence of r-hGH. Abbreviations and symbols: ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir; EFV, efavirenz; DLV, delavirdine; NVP, nevirapine; NFV, nelfinavir; APV, amprenavir; LPV, lopinavir; solid bars, control; open bars r-hGH at 10 ng/ml; shaded bars, r-hGH at 20 ng/ml.

FIG. 2.

IC50s of eight ARVs for five drug-resistant clinical of HIV-1 isolates (a to e) in the presence and the absence of r-hGH (logarithmic scale). The results presented in panels a to e correspond to those for isolates 3 to 7, respectively, in Table 1. Each experiment was performed with three replicate samples and was repeated on at least two different occasions. In no instance were significant differences in IC50s observed between studies performed in the presence or absence of r-hGH. Abbreviations and symbols: ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir; EFV, efavirenz; DLV, delavirdine; NVP, nevirapine; NFV, nelfinavir; APV, amprenavir; LPV, lopinavir; solid bars, control; open bars r-hGH at 10 ng/ml; shaded bars, r-hGH at 20 ng/ml.

Clinical studies in both the pre-HAART era (15, 17, 19, 20) and the HAART era (11) have shown that r-hGH can be effective and well tolerated as therapy for AIDS-related wasting. hGH has anabolic effects, which result in an increase in lean body mass (6, 10, 14). In contrast to other anabolic agents, hGH also has anticatabolic actions mediated via the direct effects on cells, the release of insulin-like growth factor type 1, and the protein-sparing effects of lipid oxidation (2, 5, 10, 19, 21). Given the clinical benefits of r-hGH in patients with AIDS-related wasting, our findings that r-hGH has no effect on viral replication or on the antiretroviral activity of currently available ARVs are reassuring. The use of two wt and five drug-resistant HIV-1 strains contributes to the validity and clinical relevance of the study, as these strains reflect the heterogeneity of viral isolates found in patients with HIV-1 infection today.

Our data are also consistent with other in vitro studies (E. Daar, unpublished data), in which r-hGH had no effect on p24 release in a variety of cell types, including PBMCs that had been acutely infected with primary patient HIV isolates and chronically infected T-cell lines. Furthermore, r-hGH at concentrations as high as 250 ng/ml had no effect on the antiviral activities of commonly used agents.

These findings are also consistent with those of in vivo studies in the pre-HAART era, in which no increase in the plasma viral RNA load or the plasma infectious viral load was noted in patients receiving r-hGH (E. Daar, unpublished). In addition, a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial with 770 patients with AIDS-associated wasting, of whom more than 500 received r-hGH for 12 weeks while continuing with HAART, showed no changes in viral loads after 12 weeks compared with the baseline values (E. Daar, unpublished). In addition, a recent limited study showed that r-hGH could promote the replication of naïve CD4 cells in HIV-1-infected patients while not affecting the plasma viral load (11).

Hence, the present results and previous in vivo findings support the clinical use of r-hGH to treat HIV-associated wasting.

Acknowledgments

Research in the laboratories of the McGill AIDS Centre is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by a generous donation from Aldo and Diane Bensadoun. We are also grateful to Serono Inc. for a grant in support of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chou, T. 1980. Comparison of dose-effect relationships of carcinogens following low-dose chronic exposure and high-dose single injection: an analysis by median-effect principle. Carcinogenesis 1:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copeland, K., and K. Nair. 1994. Acute growth hormone effects on amino acid and lipid metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 78:1040-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu, Z., Q. Gao, X. Li, M. A. Parniak, and M. A. Wainberg. 1992. Novel mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase gene that encodes cross-resistance to 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine. J. Virol. 66:7128-7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haverstick, L., M. Rothkopf, G. Stanislaus, and U. Suchner. 1991. Growth hormone, its effect on protein metabolism and clinical implications. Top. Clin. Nutr. 7:52-62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horber, F., and M. Haymond. 1990. Human growth hormone prevents the protein catabolic side effects of prednisone in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 86:265-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotler, D., J. Wang, and R. J. Pierson. 1985. Body composition studies in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 42:1255-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurence, J., B. Grimison, and A. Gonenne. 1992. Effect of recombinant human growth hormone on acute and chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro. Blood 79:467-472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loemba, H., B. Brenner, M. A. Parniak, S. Ma'ayan, B. Spira, D. Moisi, M. Oliveira, M. Detorio, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Genetic divergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Ethiopian clade C reverse transcriptase (RT) and rapid development of resistance against nonnucleoside inhibitors of RT. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2087-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson, J. M., R. J. Smith, and D. W. Wilmore. 1988. Growth hormone stimulates protein synthesis during hypocaloric parenteral nutrition. Ann. Surg. 208:136-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulligan, K., C. Grunfeld, M. Hellerstein, R. Neese, and M. Schambelan. 1993. Anabolic effects of recombinant human growth hormone in patients with wasting associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 77:956-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano, L. A., J. C. Lo, M. B. Gotway, K. Mulligan, J. D. Barbour, D. Schmidt, R. M. Grant, R. A. Halvorsen, M. Schambelan, and J. M. McCune. 2002. Increased thymic mass and circulating naive CD4 T cells in HIV-1-infected adults treated with growth hormone. AIDS 16:1103-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polsky, B., D. Kotler, and C. Steinhart. 2001. HIV-associated wasting in the HAART era: guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDs 15:411-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roubenoff, R. 2000. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome wasting, functional performance, and quality of life. Am. J. Managed Care 6:1003-1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell-Jones, D. L., A. J. Weissberger, S. B. Bowes, J. M. Kelly, M. Thomason, A. M. Umpleby, R. H. Jones, and P. H. Sonksen. 1993. The effects of growth hormone on protein metabolism in adult growth hormone deficient patients. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxford) 38:427-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schambelan, M., K. Mulligan, C. Grunfeld, E. S. Daar, A. LaMarca, D. P. Kotler, J. Wang, S. A. Bozzette, J. B. Breitmeyer, et al. 1996. Recombinant human growth hormone in patients with HIV-associated wasting. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 125:873-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinhart, C. R. 2001. HIV-associated wasting in the era of HAART: a practice-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. AIDS Read. 11:557-560, 566-569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai, V. W., M. Schambelan, H. Algren, C. Shayevich, and K. Mulligan. 2002. Effects of recombinant human growth hormone on fat distribution in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-associated wasting. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1258-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wainberg, M. A., M. D. Miller, Y. Quan, H. Salomon, A. S. Mulato, P. D. Lamy, N. A. Margot, K. E. Anton, and J. M. Cherrington. 1999. In vitro selection and characterization of HIV-1 with reduced susceptibility to PMPA. Antivir. Ther. 4:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward, H., D. Halliday, and A. Sim. 1987. Protein and energy metabolism with biosynthetic human growth hormone after gastrointestinal surgery. Ann. Surg. 206:56-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waters, D., J. Danska, K. Hardy, F. Koster, C. Qualls, D. Nickell, S. Nightingale, N. Gesundheit, D. Watson, and D. Schade. 1996. Recombinant human growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1, and combination therapy in AIDS-associated wasting. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 125:865-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler, T., L. Young, E. Ferrari-Baliviera, R. Demling, and D. Wilmore. 1990. Use of human growth hormone combined with nutritional support in a critical care unit. J. Parenteral Enteral Nutr. 14:574-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]