Abstract

The emergence of antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria has led to efforts to find alternative antimicrobial therapeutics to which bacteria will not be easily able to develop resistance. One of these may be the combination of nontoxic dyes (photosensitizers [PS]) and visible light, known as photodynamic therapy, and we have reported its use to treat localized infections in animal models. While it is known that gram-positive species are generally susceptible to photodynamic inactivation (PDI), the factors that govern variation in degrees of killing are unknown. We used isogenic pairs of wild-type and transposon mutants deficient in capsular polysaccharide and slime production generated from Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus to examine the effects of extracellular slime on susceptibility to PDI mediated by two cationic PS (a polylysine-chlorine6 conjugate, pL-ce6, and methylene blue [MB]) and an anionic molecule, free ce6, and subsequent exposure to 665-nm light at 0 to 40 J/cm2. Free ce6 gave more killing of mutant strains than wild type, despite the latter taking up more PS. Log-phase cultures were killed more than stationary-phase cultures, and this correlated with increased uptake. The cationic pL-ce6 and MB gave similar uptakes and killing despite a 50-fold difference in incubation concentration. Differences in susceptibility between strains and between growth phases observed with free ce6 largely disappeared with the cationic compounds despite significant differences in uptake. These data suggest that slime production and stationary phase can be obstacles against PDI for gram-positive bacteria but that these obstacles can be overcome by using cationic PS.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is based on the concept that a nontoxic dye known as a photosensitizer (PS) can be preferentially localized in certain tissues or cells and subsequently activated by low doses of visible light of the appropriate wavelength to generate singlet oxygen and free radicals that are cytotoxic to target cells (11). Microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, yeasts, and viruses can also be killed by visible light after their treatment with an appropriate PS (14). Several studies have demonstrated that gram-positive bacteria are particularly susceptible to photodynamic inactivation (PDI) (5, 25), but gram-negative bacteria are significantly resistant to many PS commonly used in PDT of tumors (24). This resistance has been overcome by the use of cationic PS (29), conjugates of PS with cationic polymers (35, 40) or by coadministration of permeabilizing peptides (33). PDT has been proposed as an alternative antibacterial therapy to combat the worldwide rise in antibiotic resistance among pathogenic microbes (14, 42). Our laboratory has recently demonstrated the use of topically administered PDT to treat localized wound infections in mice (15, 17).

Rates of hospital-acquired staphylococcal infection have risen substantially in the United States over the last decade due to changes in medical practice (increasing use of implantable devices) and in types of patient (increased use of immunosuppressive therapies) (41). Widespread use of antibiotic therapy has helped select more resistant organisms, among which methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus that has also acquired vancomycin resistance is particularly problematic (39). Intrinsic microbiological factors such as encapsulation and slime production allow these organisms to adhere to protein-coated foreign bodies and basement membranes, enabling them to initiate infection and grow as biofilms (13). Moreover, these properties together with virulence factors such as secretion of extracellular enzymes aid their resistance to host defenses (38) as well as to many antibiotics (21). The biofilm contains the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin molecule (PS/A) and a related compound termed polysaccharide intercellular adhesin, collectively known as slime, which mediate cell adherence to biomaterials (28).

It is likely that the efficiency of the process of PDI of bacteria depends on the degree to which the PS binds to bacteria and penetrates to a sensitive intracellular site. However, it is uncertain what is the role of extracellular slime in this process. Slime could either increase or decrease the binding of the PS to the bacterial cell and, independently of binding, could act as a barrier to penetration of the PS into the interior of the organism, where the generation of reactive oxygen species would be more likely to lead to cell death. Slime production in staphylococci is known to be significantly higher in the stationary phase than in the log phase (4), and interactions between slime and PS could therefore explain some conflicting literature data on the relative susceptibility of stationary- and log-phase bacteria to PDI (20).

In this report we examine the uptake of PS and subsequent light-mediated bacterial killing in two pairs of isogenic wild-type and mutant staphylococci, S. aureus and the coagulase negative Staphylococcus epidermidis. We chose to compare the anionic PS, free chlorine6 (ce6) and the macromolecular conjugate poly-l-lysine-chlorine6 (pL-ce6) that we have previously reported (16) to be efficient in mediating the PDI of S. aureus, together with the cationic phenothiazinium dye, methylene blue (MB) that has been well studied in the literature as an antibacterial PS (43). These compounds can all be efficiently activated by light of the same wavelength (665 nm).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Two pairs of isogenic wild-type and transposon mutant strains deficient in production of the biofilm polysaccharide were used. These were generous gifts from Gerald B. Pier (Channing Laboratory, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.). One clinical isolate was strain S. epidermidis M187 (PS/A+ slime+), and its isogenic mutant S. epidermidis M187sn3 (PS/A− slime−) was also used (31). The second isolate was S. aureus SA113 (PS/A+ slime+) (27) and its mutant S. aureus SA113sn3 (PS/A− slime−) (9). Each mutant strain contains a single copy of the 13.6-kb transposable unit Tn917LTV1 incorporated into the wild-type parent genome at a unique site (31). This insertion results in cessation of the expression of PS/A and slime (sn3). Bacteria were routinely grown on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar or BHI broth at 37°C with shaking. Log-phase bacteria were grown to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.6 corresponding to 108 CFU per ml. Stationary-phase bacteria were grown overnight to an optical density at 650 nm of more than 3 and were subsequently diluted to give 108 CFU per ml. For uptake experiments these cultures were adjusted to give suspensions of 109 organisms per ml in order to allow cellular protein to be measured.

PS.

MB was from Aldrich (Milwaukee, Wis.) and was dissolved in water to give a 1 mM stock solution. ce6 was obtained from Frontier Scientific (Logan, Utah) and was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH to give a 1 mM stock solution and neutralized immediately before use. The pL-ce6 conjugate was prepared as previously described (15) (it consisted of a pL chain with an average length of 110 lysine residues and an average of four ce6 molecules per chain), and concentrations were expressed as molar ce6 equivalent.

Biofilm assays.

The phenotypes of the strains were verified by examining their ability to produce slime and biofilms. Colonies were grown on Congo red agar as described by Freeman et al. (12). BHI broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) 37 g/liter, sucrose (50 g/liter), and agar (10 g/liter) were autoclaved, and a separately autoclaved Congo red solution (Aldrich) was added at 55°C to give a final concentration of 0.8 g/liter. Colony morphology was examined after 24 h at 37°C. The biofilm assay was performed essentially as described by Christensen et al. (8). Briefly, Staphylococcus strains were grown overnight in tryptic soy broth. Strains were then diluted 1/200 in tryptic soy broth supplemented with 0.25% glucose, and 200 μl of this suspension was inoculated in sextuplicate to flat-bottom sterile polystyrene microtiter plates (Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Medium was removed, and the wells were gently washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then fixed for 10 min using ethanol and then were air dried. The biofilms that remained in the wells were stained with crystal violet for 1 min. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader (model Victor-2 1420; EG&G Wallac, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Uptake studies.

Bacteria suspensions (109 cells/ml) were incubated in PBS in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with 1 μM ce6 equivalent of the pL-ce6 conjugate and free ce6 and 50 μM MB. Incubations were carried out in sextuplicate. The cell suspensions were centrifuged (9,000 × g, 1 min), the PS solution was aspirated, and bacteria were washed twice in 1 ml of sterile PBS and centrifuged as described above. Finally, the cell pellet was dissolved by digesting it in 3 ml of 0.1 M NaOH-1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for at least 24 h to give the cell extract as a homogenous solution. Fluorescence in the extracts was measured on a spectrofluorimeter (model FluoroMax3; SPEX Industries, Edison, N.J.). For pL-ce6 and free ce6 the excitation wavelength was 400 nm and the emission spectra of the solutions were recorded from 580 to 700 nm. For MB the excitation wavelength was 595 nm and the range for emission spectra was 598 to 700. If necessary the solution was diluted with 0.1 M NaOH-1% SDS to reach a concentration of the PS where the fluorescence response was linear. Separate fluorescence calibration curves were constructed with known amounts of pL-ce6, free ce6 and MB dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH-1% SDS. Protein content (of the entire cell extract) was then determined by a modified Lowry method (26) using bovine serum albumin dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH-1% SDS to construct calibration curves. Results were expressed as mol PS per mg cell protein.

PDI studies.

Bacteria suspensions (108/ml) were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with 1 μM ce6 equivalent of the conjugate or free ce6 and 50 μM MB in PBS as described above. Cell suspensions were centrifuged, cells were washed twice with PBS, and 1 ml of fresh PBS was added. Suspensions (1 ml) were then placed in the wells of 24-well plates. The wells were illuminated from below at room temperature in subdued room lighting. A 665-nm, 1-W diode laser (model BWF-665-1; B&W Tek, Newark, Del.) was coupled into a 1-mm-diameter optical fiber that delivered light into a lens which formed a uniform circular spot on the base of the 24-well plate 2 cm in diameter. Fluences ranged from 0 to 40 J/cm2 (0 to 13.3 min) at an irradiance of 50 mW/cm2. At intervals during the illumination when the requisite fluences had been delivered, aliquots (100 μl) were taken from each well to determine CFU. Care was taken to ensure the contents of the wells were thoroughly mixed before sampling as bacteria can settle to the bottom. The aliquots were serially diluted 10-fold in PBS to give dilutions of 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, and 10−6 times the original concentrations. Ten-microliter aliquots of each of the dilutions were streaked horizontally on square BHI agar plates as described by Jett et al. (18). Plates were streaked in triplicate and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the dark. In general three dilutions could be counted on each plate. Controls were bacteria untreated with PS or light, bacteria incubated with PS but kept in 24-well plates at room temperature covered with aluminum foil for the duration of the illumination, and bacteria exposed to light in the absence of PS. Survival fractions were routinely expressed as ratios of CFU of bacteria treated with light and PS to CFU of bacteria treated with neither.

Statistical methods.

Differences between two means were evaluated by the unpaired, two-sided Student t test, assuming equal or unequal variation in the standard deviations as appropriate. Differences between the slopes of killing curves were evaluated using linear regression analysis function contained in GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of slime production.

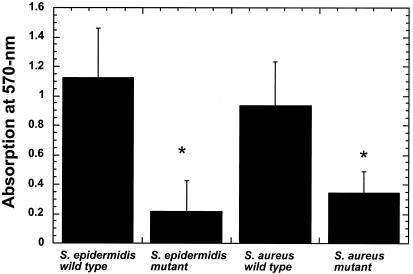

The wild-type strains produced a distinctive colony morphology on Congo red agar. When viewed from beneath, the colonies had a black appearance, and they had a dry crystalline appearance from above. Mutant strains lacked both of these characteristics, with a pink color seen from below and a soft appearance from above (data not shown). The values obtained from the quantitative biofilm assay are shown in Fig. 1. There are highly significant differences in biofilm production (P < 0.001) between the wild-type and mutant strains for both S. epidermidis and S. aureus. Although the value obtained for wild-type S. epidermidis (1.125) was higher compared to wild-type S. aureus (0.903) the difference failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.13).

FIG. 1.

Quantitative biofilm assay in tissue culture microtiter plates after 24 h at 37°C. Values are means of six measurements and bars are SD. *, mutant significantly different from wild type (P < 0.001).

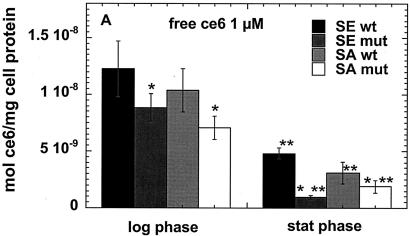

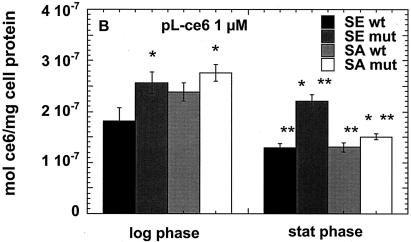

Uptake studies.

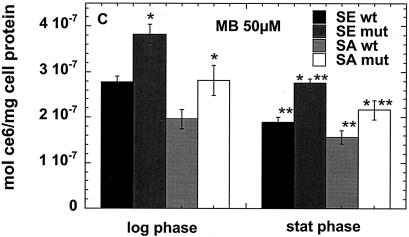

We carried out preliminary experiments to select concentrations of the three PS that would give comparable degrees of killing with modest light doses (up to 40 J/cm2). While 1 μM free ce and 1 μM ce equivalent in pL-ce6 conjugate produced comparable phototoxicity in the bacteria tested (see Fig. 3A to D), MB was completely ineffective at this concentration (data not shown). The concentration of MB necessary to produce comparable killing at a fluence of 40 J/cm2 was established to be 50 μM, and we therefore used 1 μM concentrations of free ce6 and pL-ce6 and 50 μM MB in further uptake and PDI studies. The values from the uptake experiments are shown in Fig. 2A to C. As fluorescence calibration experiments were carried out for each PS separately, the values could be expressed as moles of PS per milligram of cellular protein. Figure 2a shows the values for free ce6 for the log- and stationary-phase cultures. For both species in both growth phases the wild-type bacteria took up significantly more PS than the mutants, while log phase bacteria took up significantly more PS than the corresponding stationary-phase cultures except for the biofilm-negative mutant S. aureus strain where the uptake was similar. For the cationic pL-ce6 and MB the overall relationship between the uptake values (shown in Fig. 2B and C) obtained for each PS are quite similar. In both cases the log-phase bacteria take up significantly more PS than the stationary-phase bacteria and the mutant bacteria take up more than the corresponding wild-type strains. The absolute uptakes were >10 times higher for the cationic pL-ce6 compared to the anionic free ce6 (although both were added at the same concentration, i.e., 1-μM). The uptake values of the cationic MB were surprisingly similar (less than 1.5 times higher) to those of the conjugate despite MB being added at a concentration of 50 μM compared to 1 μM for conjugate.

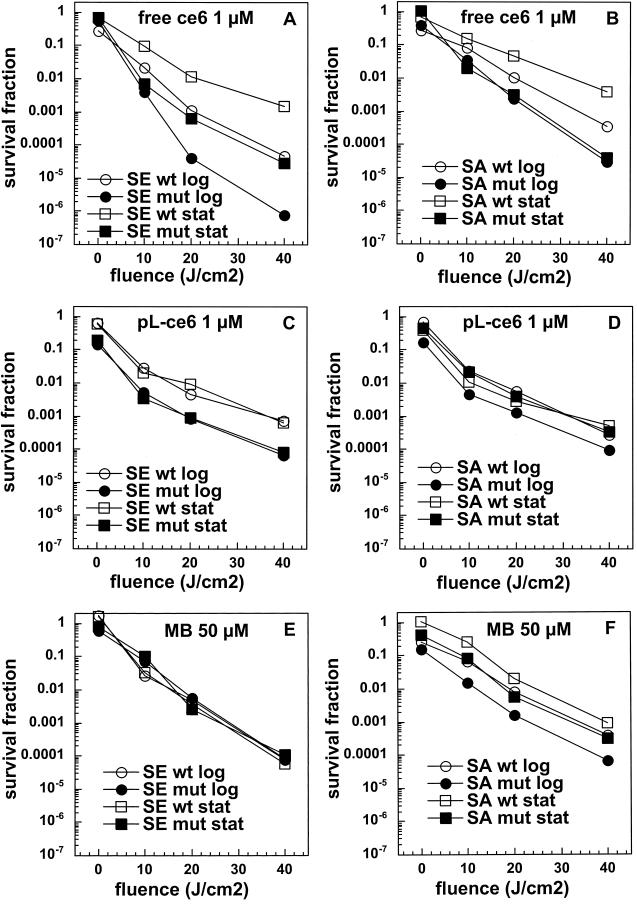

FIG. 3.

Light dose-dependent killing mediated by free ce6 (A and B), pL-ce6 (C and D), and MB (E and F) of the wild-type (wt) and mutant (mut) strains in log and stationary (stat) phase incubated with PS as described in Fig. 2. Survival fractions are expressed as ratios of CFU from bacteria treated with PS and light over CFU of bacteria treated with neither, and curves are representative of three independent experiments.

FIG. 2.

Cellular uptake of free ce6 (A), pL-ce6 (B), and MB (C) by wild-type (wt) and mutant (mut) strains in log and stationary (stat) phase. Bacteria were incubated for 30 min with 1 μM ce6 equivalent (A and B) or 50 μM MB (C), and were washed and dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH-1% SDS. Values are means of six independent measurements, bars are SD. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated between mutant and corresponding wild-type strain (*) and between stationary phase and corresponding log phase (**).

PDI.

Survival fractions for the PDI experiments were expressed as the ratios of CFU from cultures treated with both light and PS to CFU measured for cultures treated with neither PS nor light. Therefore, the survival fraction corresponding to 0 J/cm2 is a measure of the dark toxicity of the PS to the bacteria. The killing curves are shown in Fig. 3, and differences in slopes were compared for statistical significance. Free ce6 gave the greatest amount of light-mediated killing observed in the entire study (>6 logs for mutant S. epidermidis in the log phase [Fig. 3A]). More killing mediated by free ce6 for the mutant strains than for the wild-type strains for both species in both growth phases (Fig. 3A and B [P < 0.05 for S. epidermidis wild type log phase versus S. epidermidis mutant log phase, S. epidermidis wild type stationary phase versus S. epidermidis mutant stationary phase, S. aureus wild type log phase versus S. aureus mutant log phase, and S. aureus wild type stationary phase versus S. aureus mutant stationary phase]). Log-phase cultures were more easily killed than the corresponding stationary-phase cultures for S. epidermidis wild type and mutant (1 to 2 logs; P < 0.05 for S. epidermidis wild type log phase versus S. epidermidis wild type stationary phase and S. epidermidis mutant log phase versus S. epidermidis mutant stationary phase) and S. aureus wild type (1 log; P < 0.05 for S. aureus wild type log phase versus S. epidermidis wild type stationary phase); there was no difference in killing between growth phases in the case of S. aureus mutant. In general S. epidermidis strains were somewhat more easily killed than the corresponding S. aureus strains. The killing curves for the cationic pL-ce6 and MB are shown in Fig. 3C to F. There is clearly less difference in killing between wild-type and mutant strains and between log- and stationary-phase cultures than was observed for free ce6. In addition, such differences in killing as are observed seem to be mainly due to increases in dark toxicity (curves keep a parallel relationship with increasing fluences) rather than differences in light-mediated killing (curves diverge with increasing fluences). In Fig. 3C the mutant S. epidermidis is killed about 1 log more than the wild-type strain after incubation with 1 μM pL-ce6 in both growth phases while for S. aureus only the log phase mutant is killed slightly more than the others (Fig. 3D). Conversely, after incubation with MB the S. epidermidis wild-type and mutant strains were killed equally in both growth phases (Fig. 3E), while somewhat greater differences were observed for S. aureus especially between log and stationary, and between wild type and mutant in the stationary phase.

When the killing curves are compared to the uptake plots in Fig. 2 the following observations can be made. For free ce6 the differences in uptake between wild-type and mutant strains are exactly opposite to the differences in PDI killing. In all cases the wild-type strains take up more ce6 than the corresponding mutant strains, while the wild-type strains are killed less than the mutant strains after illumination. The fact that this pattern is observed for both species and for both growth phases increases the confidence level that it is a real effect. By contrast, in the cases of pL-ce6 and MB the differences in uptake largely parallel the differences in killing. The increased killing observed after incubation with pL-ce6 for mutant S. epidermidis compared to wild type in both growth phases (Fig. 3C) is paralleled by increased uptake (Fig. 2B), while for S. aureus with pL-ce6 the mutant in the log phase has both the highest uptake and highest killing. For experiments with MB the S. epidermidis strains are equally killed in both growth phases despite significant differences in uptake, while for S. aureus the order of killing (log-phase mutant > stationary-phase mutant ≈ log-phase wild type > stationary-phase wild type [Fig. 3F]) is also the same as the order of uptake (Fig. 2C).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that PDI of staphylococci can be affected both by the presence or absence of extracellular slime and by the growth phase. Slime production in staphylococci is controlled by the icaADBC operon and its existence has been extensively correlated with virulence in clinical isolates from catheters (36), bacterial keratitis (32), and bovine mastitis (3). The precise chemical composition of the slime remains complex despite being extensively investigated (1, 2, 7). A recent report (19) describes poly-β(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine comprised of fractions with molecular masses of 460, 100, and 21 kDa that also vary in the extent of N-acetylation and O-succinylation.

It has been well established that for gram-positive organisms, both positively and negatively charged PS are effective in mediating PDI (23, 40). Our previous publication (16) compared the efficiency of free ce6 and two pL-ce6 conjugates with average chain lengths of 8 lysines and 37 lysines in mediating PDI of S. aureus and Escherichia coli, and concluded that for S. aureus free ce6 was the most effective PS both on an absolute basis and on a mol per cell basis. The polycationic chain, however was necessary to mediate killing of the gram-negative E. coli. Similar results were obtained in the present study where the highest killing (up to six logs) was observed with log phase mutant S. epidermidis and free ce6.

The results of the present study have shown significant differences in both the uptake and PDI efficacy of the three PS tested. In agreement with reports from other workers (30, 44), MB was not effective until a certain threshold concentration was reached (in the region of 50 μM). For the first time we have quantitated the uptake by bacteria of MB on a molar basis and have an explanation for this observation. A 50-fold higher incubation concentration is necessary to obtain comparable cellular levels to those obtained with 1-μM conjugate, and therefore both molecules are equally effective on a mol per cell basis (while free ce6 is considerably more effective on a mol per cell basis).

Although the overall ionic charge borne by the slime has not been studied in detail, there are reports implicating hydrophobic interactions between the bacterial slime and surfaces (often synthetic polymers) causing bacterial adhesion and hence determining pathogenicity (10, 37). Therefore, it might be supposed that characteristics of slime play a significant role in the determining the binding and intracellular penetration of PS that vary in charge and hydrophobicity. It is possible, for example, that the slime could increase the binding of either cationic or anionic PS molecules (depending on the overall charge and hydrophobicity of the slime) but could act as a barrier to their penetration to more sensitive intracellular locations. The fact that the uptake of the anionic free ce6 was much higher for the slime-producing strains than the mutants, while the killing was much less, could be explained by the slime barrier trapping the PS on the outside of the cell due to ionic or hydrophobic interactions and therefore reducing the amount of PS that was able to penetrate to the plasma membrane which is thought to be one of the important sites of PDI-mediated damage. In addition, a large amount of PS trapped in the slime layer could act as an optical shield by absorbing photons and generating relatively harmless reactive oxygen products outside the cell, while reducing the number of photons that penetrate to the PS located inside the cell. The somewhat-larger differences in ce6 uptake between wild-type and mutant S. epidermidis compared to S. aureus agrees with the data in Fig. 1 showing a higher difference in slime production between wild-type and mutant S. epidermidis compared to S. aureus. The fact that the differences in cellular PS uptake between wild type and mutants were reversed for both the cationic pL-ce6 and MB suggests that these compounds which are significantly more hydrophilic and water soluble than ce6 bind better to the anionic structures underlying the slime such as teichoic acids, rather than the slime itself. Even though the uptake of these compounds was higher for the mutants compared to the wild-type strains, the killing was roughly equal, implying that the increased PS accumulated by the mutants is not located at a particularly sensitive location.

The present findings show that for the anionic free ce6 there was a significant and light dose-dependent reduction in killing in the stationary phase compared to log phase. That this was seen for both the mutant and wild-type strains of both species suggests that the increased resistance was not solely due to the increase in slime production in the stationary phase. By contrast, differences between killing of growth phases were largely abrogated by the use of the cationic species pL-ce6 and MB. There are conflicting reports in the literature on the effect of growth phase on the susceptibility of bacteria to PDI. Nitzan et al. (34) reported that S. aureus was more resistant to PDI in the stationary phase using deuteroporphyrin (a molecule with structure similar to that of ce6), while Wilson and Pratten (45) found no difference between S. aureus growth phases using aluminum phthalocyanine disulfonate as PS. Bhatti et al. (6) reported that the gram-negative bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis was more resistant in the stationary phase to PDI using toluidine blue O (a molecule with similar structure to MB), while Komerik and Wilson (20) found no difference in killing between growth phases using the same compound and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E. coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Further work is necessary to more precisely define the relationships between growth phase, PS uptake, and killing of various bacterial species.

Pathogenic staphylococci frequently express slime and form biofilms having characteristics of stationary-phase growth. Infections characterized by these biofilms are often intractable and require prolonged treatment with antibiotics (22). These data suggest that PDT mediated by cationic PS might be an effective therapy for localized staphylococcal infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant R01AI050875 to M.R.H.) and by the Department of Defense Medical Free Electron Laser Program (N00014-94-1-0927).

We are grateful to Gerald B. Pier for generously providing the bacterial strains, to George Tegos for a critical reading of the manuscript, and to Zaraq Khan for assistance with the slime assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammendolia, M. G., R. Di Rosa, L. Montanaro, C. R. Arciola, and L. Baldassarri. 1999. Slime production and expression of the slime-associated antigen by staphylococcal clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3235-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciola, C. R., L. Baldassarri, and L. Montanaro. 2001. Presence of icaA and icaD genes and slime production in a collection of staphylococcal strains from catheter-associated infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2151-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baselga, R., I. Albizu, and B. Amorena. 1994. Staphylococcus aureus capsule and slime as virulence factors in ruminant mastitis. A review. Vet. Microbiol. 39:195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayston, R., and J. Rodgers. 1990. Production of extra-cellular slime by Staphylococcus epidermidis during stationary phase of growth: its association with adherence to implantable devices. J. Clin. Pathol. 43:866-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertoloni, G., B. Salvato, M. Dall'Acqua, M. Vazzoler, and G. Jori. 1984. Hematoporphyrin-sensitized photoinactivation of Streptococcus faecalis. Photochem. Photobiol. 39:811-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatti, M., A. MacRobert, S. Meghji, B. Henderson, and M. Wilson. 1997. Effect of dosimetric and physiological factors on the lethal photosensitization of Porphyromonas gingivalis in vitro. Photochem. Photobiol. 65:1026-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen, G. D., L. P. Barker, T. P. Mawhinney, L. M. Baddour, and W. A. Simpson. 1990. Identification of an antigenic marker of slime production for Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 58:2906-2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen, G. D., W. A. Simpson, J. J. Younger, L. M. Baddour, F. F. Barrett, D. M. Melton, and E. H. Beachey. 1985. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:996-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramton, S. E., C. Gerke, N. F. Schnell, W. W. Nichols, and F. Gotz. 1999. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 67:5427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das, S. C., K. N. Kapoor, and M. Mukhopadhyay. 2001. Comparative evaluation of hydrophobicity measures for virulence determination of Staphylococcus epidermidis from hospitalized patients and healthy individuals. Indian J. Med. Res. 114:160-163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty, T. J., C. J. Gomer, B. W. Henderson, G. Jori, D. Kessel, M. Korbelik, J. Moan, and Q. Peng. 1998. Photodynamic therapy. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 90:889-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman, D. J., F. R. Falkiner, and C. T. Keane. 1989. New method for detecting slime production by coagulase negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Pathol. 42:872-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldmann, D. A., and G. B. Pier. 1993. Pathogenesis of infections related to intravascular catheterization. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:176-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamblin, M. R., and T. Hasan. Photodynamic therapy: a new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hamblin, M. R., D. A. O'Donnell, N. Murthy, C. H. Contag, and T. Hasan. 2002. Rapid control of wound infections by targeted photodynamic therapy monitored by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Photochem. Photobiol. 75:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamblin, M. R., D. A. O'Donnell, N. Murthy, K. Rajagopalan, N. Michaud, M. E. Sherwood, and T. Hasan. 2002. Polycationic photosensitizer conjugates: effects of chain length and Gram classification on the photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:941-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamblin, M. R., T. Zahra, C. H. Contag, A. T. McManus, and T. Hasan. 2003. Optical monitoring and treatment of potentially lethal wound infections in vivo. J Infect. Dis. 187:1717-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jett, B. D., K. L. Hatter, M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1997. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. BioTechniques 23:648-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce, J. G., C. Abeygunawardana, Q. Xu, J. C. Cook, R. Hepler, C. T. Przysiecki, K. M. Grimm, K. Roper, C. C. Ip, L. Cope, D. Montgomery, M. Chang, S. Campie, M. Brown, T. B. McNeely, J. Zorman, T. Maira-Litran, G. B. Pier, P. M. Keller, K. U. Jansen, and G. E. Mark. 2003. Isolation, structural characterization, and immunological evaluation of a high-molecular-weight exopolysaccharide from Staphylococcus aureus. Carbohydr. Res. 338:903-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komerik, N., and M. Wilson. 2002. Factors influencing the susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria to toluidine blue O-mediated lethal photosensitization. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:618-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konig, C., S. Schwank, and J. Blaser. 2001. Factors compromising antibiotic activity against biofilms of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis, K. 2001. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malik, Z., J. Hanania, and Y. Nitzan. 1990. Bactericidal effects of photoactivated porphyrins-an alternative approach to antimicrobial drugs. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 5:281-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik, Z., H. Ladan, and Y. Nitzan. 1992. Photodynamic inactivation of Gram-negative bacteria: problems and possible solutions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 14:262-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik, Z., H. Ladan, Y. Nitzan, and B. Ehrenberg. 1990. The bactericidal activity of a deuteroporphyrin-hemin mixture on gram-positive bacteria. A microbiological and spectroscopic study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 6:419-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markwell, M. A., S. M. Haas, L. L. Bieber, and N. E. Tolbert. 1978. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal. Biochem. 87:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxe, I., C. Ryden, T. Wadstrom, and K. Rubin. 1986. Specific attachment of Staphylococcus aureus to immobilized fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 54:695-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenney, D., J. Hubner, E. Muller, Y. Wang, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 1998. The ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect. Immun. 66:4711-4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merchat, M., G. Bertolini, P. Giacomini, A. Villanueva, and G. Jori. 1996. Meso-substituted cationic porphyrins as efficient photosensitizers of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 32:153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millson, C. E., M. Wilson, A. J. Macrobert, J. Bedwell, and S. G. Bown. 1996. The killing of Helicobacter pylori by low-power laser light in the presence of a photosensitiser. J. Med. Microbiol. 44:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller, E., J. Hubner, N. Gutierrez, S. Takeda, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 1993. Isolation and characterization of transposon mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis deficient in capsular polysaccharide/adhesin and slime. Infect. Immun. 61:551-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nayak, N., and G. Satpathy. 2000. Slime production as a virulence factor in Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated from bacterial keratitis. Indian J. Med. Res. 111:6-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitzan, Y., M. Gutterman, Z. Malik, and B. Ehrenberg. 1992. Inactivation of gram-negative bacteria by photosensitized porphyrins. Photochem. Photobiol. 55:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nitzan, Y., B. Shainberg, and Z. Malik. 1989. The mechanism of photodynamic inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus by deuteroporphyrin. Curr. Microbiol. 19:265-269. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polo, L., A. Segalla, G. Bertoloni, G. Jori, K. Schaffner, and E. Reddi. 2000. Polylysine-porphycene conjugates as efficient photosensitizers for the inactivation of microbial pathogens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 59:152-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rupp, M. E., J. S. Ulphani, P. D. Fey, and D. Mack. 1999. Characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin/hemagglutinin in the pathogenesis of intravascular catheter-associated infection in a rat model. Infect. Immun. 67:2656-2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt, H., E. Schloricke, R. Fislage, H. A. Schulze, and R. Guthoff. 1998. Effect of surface modifications of intraocular lenses on the adherence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 287:135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiau, A. L., and C. L. Wu. 1998. The inhibitory effect of Staphylococcus epidermidis slime on the phagocytosis of murine peritoneal macrophages is interferon-independent. Microbiol. Immunol. 42:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, T. L., M. L. Pearson, K. R. Wilcox, C. Cruz, M. V. Lancaster, B. Robinson-Dunn, F. C. Tenover, M. J. Zervos, J. D. Band, E. White, W. R. Jarvis, et al. 1999. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soukos, N. S., L. A. Ximenez-Fyvie, M. R. Hamblin, S. S. Socransky, and T. Hasan. 1998. Targeted antimicrobial photochemotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2595-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor, L. 1997. MRSA. Nurs. Stand. 11:1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wainwright, M. 1998. Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:13-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wainwright, M., D. A. Phoenix, S. L. Laycock, D. R. Wareing, and P. A. Wright. 1998. Photobactericidal activity of phenothiazinium dyes against methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 160:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, M., J. Dobson, and W. Harvey. 1992. Sensitisation of oral bacteria to killing by low-power laser irradiation. Curr. Microbiol. 25:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson, M., and J. Pratten. 1995. Lethal photosensitisation of Staphylococcus aureus in vitro: effect of growth phase, serum, and pre-irradiation time. Laser Surg. Med. 16:272-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]