Abstract

While the influence of water in Helicobacter pylori culturability and membrane integrity has been extensively studied, there are little data concerning the effect of this environment on virulence properties. Therefore, we studied the culturability of water-exposed H. pylori and determined whether there was any relation with the bacterium’s ability to adhere, produce functional components of pathogenicity and induce inflammation and alterations in apoptosis in an experimental model of human gastric epithelial cells. H. pylori partially retained the ability to adhere to epithelial cells even after complete loss of culturability. However, the microorganism is no longer effective in eliciting in vitro host cell inflammation and apoptosis, possibly due to the non-functionality of the cag type IV secretion system. These H. pylori-induced host cell responses, which are lost along with culturability, are known to increase epithelial cell turnover and, consequently, could have a deleterious effect on the initial H. pylori colonisation process. The fact that adhesion is maintained by H. pylori to the detriment of other factors involved in later infection stages appears to point to a modulation of the physiology of the pathogen after water exposure and might provide the microorganism with the necessary means to, at least transiently, colonise the human stomach.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, virulence properties, water, culturability, infection

Helicobacter pylori is an important human pathogen that causes chronic gastritis and is associated with the development of more severe diseases, such as peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer (Blaser & Atherton 2004). Since the isolation of H. pylori, numerous studies have been published addressing the prevalence and epidemiology of infection (Brown 2000, Kikuchi & Dore 2005, Queiroz & Luzza 2006), its relationship with disease, the identification and characterisation of virulence factors and their role in pathogenesis (Prinz et al. 2003, Blaser & Atherton 2004, Figueiredo et al. 2005). However, it is still unclear to the scientific community how H. pylori is transmitted (Azevedo et al. 2009).

The most widely accepted routes of transmission are the oral-oral, faecal-oral and gastric-oral routes. Nevertheless, an increasing number of works report the identification of H. pylori in external environmental reservoirs, such as food, domestic animals and, most significantly, water (Dore et al. 2001, Park et al. 2001, Fujimura et al. 2002, Watson et al. 2004, Safaei et al. 2011). In fact, several epidemiological studies have concluded that the drinking water source, or drinking water-related conditions, was a risk factor for H. pylori acquisition (Karita et al. 2003, Krumbiegel et al. 2004, Fujimura et al. 2008). Molecular methods, such as fluorescence in situ hybridisation and polymerase chain reaction, have been used to detect the presence of H. pylori DNA in water and water-associated biofilms from wells, rivers and water distribution networks (Flanigan & Rodgers 2003, Fujimura et al. 2004, Bragança et al. 2005, Khan et al. 2012). However, the demonstration that H. pylori can be detected in water does not imply that the microorganism can then colonise the human host. In fact, while it has been shown that water-exposed H. pylori total cell counts did not decrease for a period of two years at 4ºC (Shahamat et al. 1993), the complete loss of culturability of the microorganism takes less than 10 h at temperatures over 20ºC (Adams et al. 2003, Azevedo et al. 2004). This transition to the non-culturable state is typically accompanied by a morphological transition of the bacteria from spiral to coccoid form (Andersen & Rasmussen 2009). Depending on the authors, the latter state has been considered a manifestation of cell death (Kusters et al. 1997) or a cellular adaptation to less than optimal environments (Azevedo et al. 2007a). In the determination of the physiological state of these non-culturable bacteria, which are still able to retain their structure for a much longer period, lies the key to our understanding of the exact role of water in H. pylori transmission. More specifically, it is important to address the effect of water exposure on several H. pylori mechanisms that are, under favourable conditions, able to induce a response in host cells. At the moment, apart from a few studies that concluded that the water-induced coccoid form of H. pylori can colonise the gastric mucosa and cause gastritis in mice (Cellini et al. 1994, She et al. 2003), there is still a lack of information regarding the capacity of water-exposed bacteria to induce a response in host cells.

In this study, we assessed the culturability of water-exposed H. pylori and determined whether this bacterium retains the capacity to adhere and elicit host cell responses, such as inflammation and apoptosis, using an experimental model of human gastric epithelial cells. Because these host cell responses may be related to components of bacterial pathogenicity, we also evaluated the capacity of water-exposed H. pylori to assemble a functional cag type IV secretion system (T4SS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions - The experiments were performed with H. pylori 26695, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The bacteria were grown in tryptic soy agar (TSA) supplemented with 5% sheep blood (BioMérieux, France) and incubated at 37ºC under a microaerophilic atmosphere for 48 h.

Water-exposed H. pylori - After 48 h of culture growth, H. pylori was harvested from TSA plates and suspended in 5 mL of autoclaved tap water in a 109 bacteria/mL concentration. The suspensions were kept at 25ºC under aerophilic conditions. The bacteria were then exposed to water for 2 h, 6 h, 24 h and 48 h. H. pylori inocula that were not exposed to water were used as controls.

Culturability - The number of culturable bacteria at the different time points was determined by plating serial dilutions of the suspensions on TSA plates containing 5% sheep blood. The culturability was analysed by comparing the number of colony-forming units of each time point.

Cell line maintenance and bacterial co-cultures - The AGS cells, derived from a human gastric carcinoma, were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Pen-Strep (Invitrogen) at 37ºC and kept under a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. All co-culture experiments of H. pylori with the AGS cells were performed at a multiplicity of infection of 100. The co-cultures were maintained at 37ºC under a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Adhesion assay - An H. pylori suspension corresponding to the different times of water exposure was added to the AGS cells and the plate was gently agitated for 30 min at 37ºC. The cultures were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 1% phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. Bacterial adhesion was determined by ELISA as previously described (McGuckin et al. 2007) using a rabbit polyclonal anti-H. pylori (Cell Marque) and an anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) as a secondary antibody. The binding was visualised after incubation with tetramethylbenzidine and 1 M HCl. The absorbance was read at 450 nm. The controls for the H. pylori binding to the wells experiment comprised wells with no AGS cells, to which bacteria were added and allowed to adhere to the plastic before fixation. The negative controls contained neither AGS cells nor H. pylori. The bacterial adhesion was expressed as a percentage of the adhesion to AGS cells of H. pylori that were not exposed to water.

Interleukin (IL)-8 production - The AGS cells were grown in six-well plates for 48 h in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS at 37ºC and 5% CO2. Bacterial suspensions corresponding to each water exposure time period were added to the cells and incubated for 24 h at 37ºC. The IL-8 levels were detected in co-culture supernatants by ELISA using the Quantikine Human CXCL8/IL8 kit (R&D Systems, USA).

Apoptosis assay - The AGS cells were grown in six-well plates for 48 h in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS at 37ºC and 5% CO2. A volume of bacterial suspension corresponding to each water exposure time period was added to the cells and incubated for 24 h at 37ºC. Apoptotic cell death was determined by the terminal uridine deoxynucleotide nick end-labelling assay (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche Diagnostics). Apoptotic cells were detected using a Leica DM IRE2 fluorescence microscope.

Western blot (WB) analysis - The co-cultures and AGS uninfected control cells were lysed in cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% NP-40, 3 mM sodium vanadate, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/mL aprotinin and 10 µg/mL leupeptin) and the lysates were separated by 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred onto Hybond nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham), which were then blocked with 4% BSA or 5% non-fat milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20. The membranes were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against tyrosine phosphorylated residues (α-PY-99, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and, after stripping, re-probed with a mouse monoclonal anti-cagA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Goat anti-rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham) were used, followed by ECL detection (Amersham). As a loading control, the membranes were also incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma).

Protein lysates of the H. pylori suspensions of each timepoint of water exposure were used as parallel controls for the amount of bacterial proteins present. Twenty micrograms of proteins of each sample was separated by 6% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Hybond nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 and incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-cagA or with rabbit polyclonal anti-urease B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies.

Statistical analyses - The data were analysed with Student’s t test using Statview for Windows software v.5.0 (SAS Institute Inc, USA) and were expressed as the mean values of, unless otherwise stated, three independent experiments ± standard deviations. Differences in data values were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

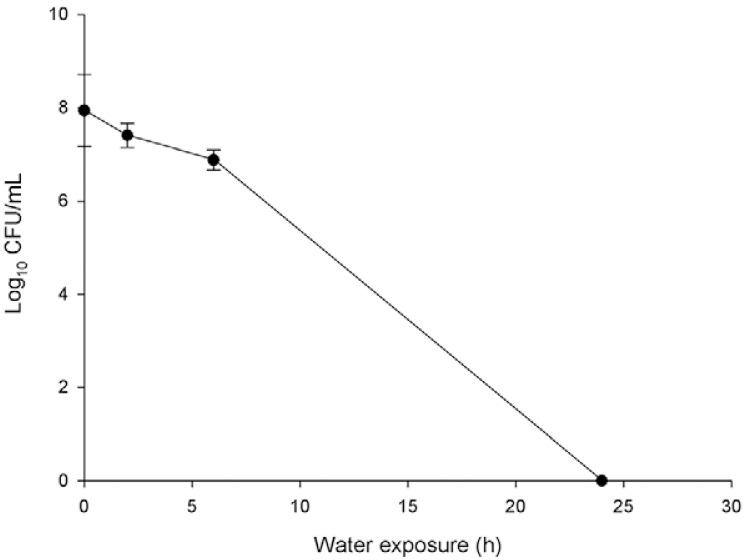

H. pylori culturability after water exposure - The culturability of H. pylori was evaluated after 0 h, 2 h, 6 h, 24 h and 48 h of water exposure. Based on previous studies (Adams et al. 2003, Azevedo et al. 2004), we anticipated that the longest timepoints would be sufficient to turn the bacterium into the non-culturable state. The results obtained confirmed our expectations, as the culturability of H. pylori progressively decreased and, after 24 h of water exposure, H. pylori was no longer culturable (Fig. 1). The subsequent studies were performed at all time points as well and we were able to observe the modulation of the virulence properties of H. pylori as the bacteria transitioned from the culturable to non-culturable state.

Fig. 1. : effect of water exposure on Helicobacter pylori culturability. After water exposure, bacteria suspension was platted on tryptic soy agar plates and incubated for seven days at 37ºC in microaerophilic conditions. The colony-forming units (CFUs) formed were counted to assess the culturability. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

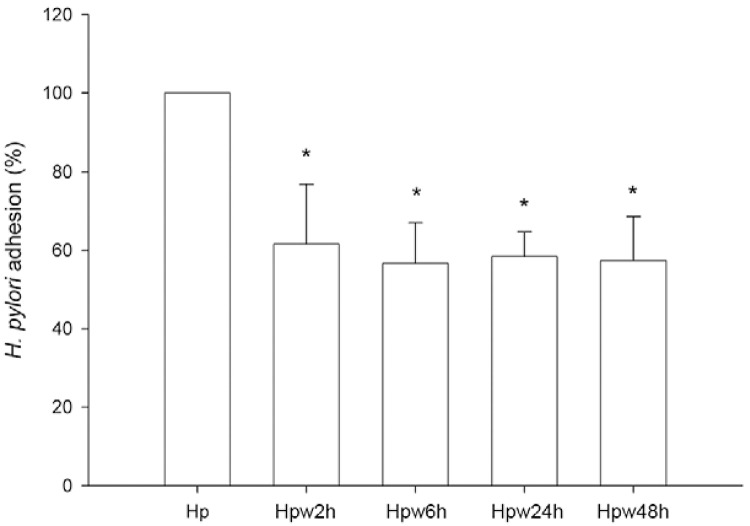

Influence of water exposure on the adhesion of H. pylori to host cells - To assess whether the adherence ability of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells is altered by the contact of the bacterium with water, we performed an adhesion assay in an ELISA format using the human gastric epithelial AGS cell line. Whereas exposure of H. pylori to water for only 2 h led to a statistically significant decrease in its ability to adhere to AGS cells (p < 0.05), the adhesion levels remained constant for bacteria that were exposed to water for longer time periods (Fig. 2). Compared to non-exposed H. pylori, the decrease in adhesion of water-exposed bacteria was approximately 40%. Nevertheless, the observation that water-exposed H. pylori are still capable of adhering to cells suggests that in these conditions, the bacterium may still exert effects on host gastric cells.

Fig. 2. : effect of water exposure on Helicobacter pylori adhesion to host epithelial cells. AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 inocula that have been exposed to water for 2 h (Hpw2h), 6 h (Hpw6h), 24 h (Hpw24h) and 48 h (Hpw48h) at a multiplicity of infection of 100. As control, H. pylori 26695 that was not exposed to the water was used (Hp). Cells were washed to remove non-adherent bacteria and adhesion was evaluated by ELISA. Data are expressed as percentage of control. Graphics represent mean ± standard deviation and are representative of three independent experiments. Asterisks mean significantly different from non-exposed H. pylori (p < 0.05).

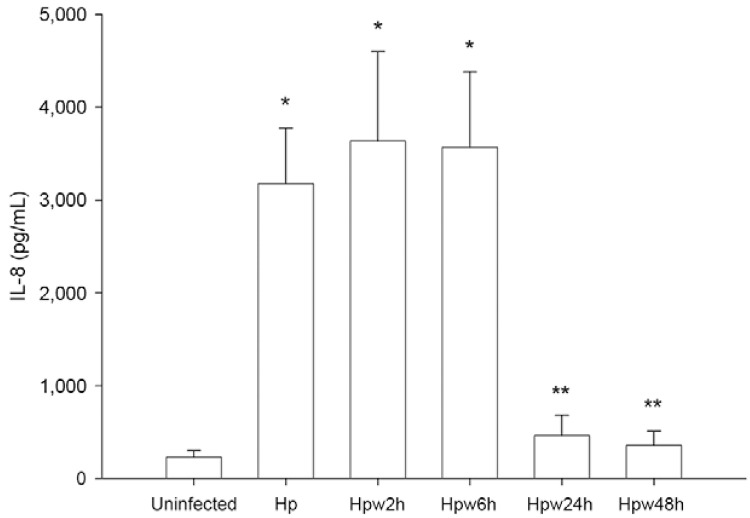

Influence of water exposure on H. pylori induction of IL-8 secretion by host cells - H. pylori leads to increased production by the epithelium of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-8 when in close contact with the gastric mucosa (Shimoyama & Crabtree 1998). Because water-exposed H. pylori were able to adhere to epithelial cells, we studied the capability of H. pylori to induce inflammation by evaluating the secretion levels of IL-8 from AGS cells infected with H. pylori inocula exposed to water for different time periods (Fig. 3). Results show that H. pylori with 2 h and 6 h of water exposure retain the ability to induce IL-8 secretion similarly to unexposed bacteria. However, after 24 h of exposure, H. pylori are no longer able to induce IL-8 production by AGS cells. Therefore, the case of inflammation induced by the bacterium appears to be more related to the culturability status of H. pylori than to the ability of this microorganism to adhere to epithelial cells. In fact, although adhesion to host cells is immediately decreased after contact with water, after short time periods (up to 6 h), adhering H. pylori cells are still able to induce pro-inflammatory IL-8 secretion in these cells.

Fig. 3. : effect of water exposure on Helicobacter pylori induction of interleukin (IL)-8 secretion by host epithelial cells. AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 inocula that have been exposed to water for 2 h (Hpw2h), 6 h (Hpw6h), 24 h (Hpw24h) and 48 h (Hpw48h) at a multiplicity of infection of 100. As control, H. pylori 26695 that was not exposed to the water was used (Hp). IL-8 production was evaluated by ELISA. Graphics represent mean ± standard deviation and are representative of three independent experiments. *: significantly different from uninfected cells; **: significantly different from non-exposed H. pylori (p < 0.05).

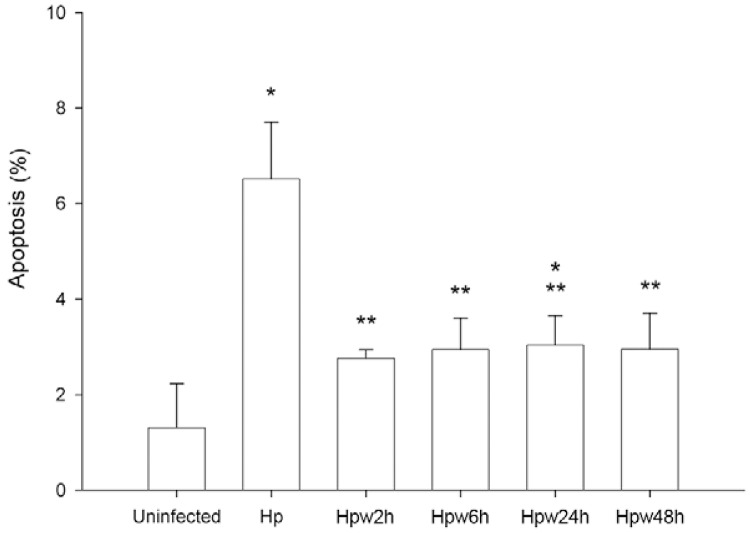

Influence of water exposure on H. pylori deregulation of host cell apoptosis - H. pylori infection has been shown to modify epithelial cell apoptosis (Moss et al. 2001, Cover et al. 2003). To elucidate whether water-exposed H. pylori is able to induce such impairment, AGS cells were infected with bacteria previously exposed to water and cell apoptosis was evaluated. As expected, non-exposed H. pylori increased AGS cell apoptosis (Fig. 4). In contrast, water-exposed H. pylori induced significantly lower levels of apoptosis than non-exposed bacteria (p < 0.01 for all water exposure times). Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were observed between apoptosis in uninfected cells and those infected with water-exposed H. pylori (p > 0.05), except for cells infected with H. pylori exposed to water for 24 h (p < 0.05). These experiments indicate that water exposure, although still permitting H. pylori to adhere, limits the influence of the bacteria on host cell apoptosis.

Fig. 4. : effect of water exposure of Helicobacter pylori on apoptosis of host epithelial cells. AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 inocula that have been exposed to water for for 2 h (Hpw2h), 6 h (Hpw6h), 24 h (Hpw24h) and 48 h (Hpw48h) at a multiplicity of infection of 100. As control, H. pylori 26695 that was not exposed to the water was used (Hp). Apoptosis was detected at single cell level using the terminal uridine deoxynucleotide nick end-labelling assay. Graphics represent mean ± standard deviation and are representative of at least two independent experiments. *: significantly different from uninfected cells; **: significantly different from non-exposed H. pylori (p < 0.05).

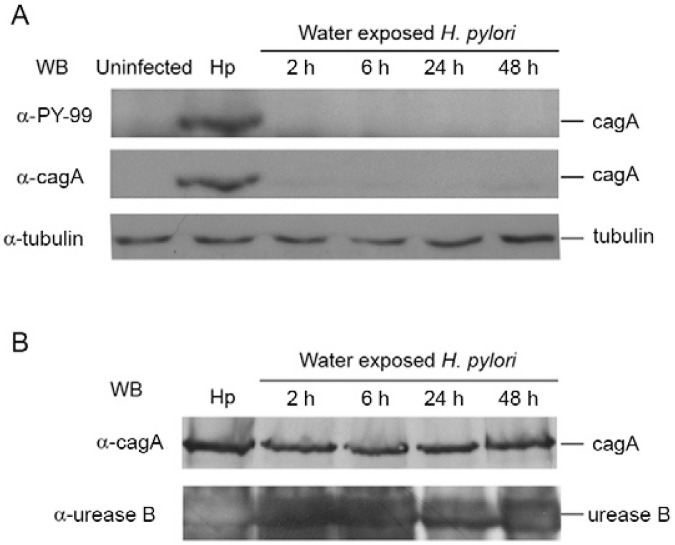

Influence of water exposure on the H. pylori cag T4SS - The T4SS is a molecular syringe that allows the injection of bacterial effectors into the host cell cytoplasm, altering host cellular processes including the induction of inflammation and deregulation of apoptosis (Segal et al. 1999, Moss et al. 2001, Viala et al. 2004, Cabral et al. 2006). After water exposure, H. pylori were still able to adhere to epithelial cells; therefore, our next experiment aimed at elucidating if water-exposed H. pylori had a functional T4SS. To assess the functionality of the T4SS, we used a WB to evaluate cagA tyrosine phosphorylation in AGS cells after infection with H. pylori 26695 inocula exposed to water at four different time periods (Fig. 5A). cagA is a T4SS effector injected into the host cell and can be phosphorylated by host protein kinases (Odenbreit et al. 2000, Backert & Selbach 2008). cagA phosphorylation only occurs inside the host cell and is an indirect measure of the T4SS functionality. H. pylori that was not exposed to water was used as a positive control for this experiment (Fig. 5A). In parallel and to control for the amount of proteins present in bacterial suspensions that were incubated in water, a WB analysis for H. pylori cagA and urease B was performed (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. : effect of water-exposure on Helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system formation. A: AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 inocula that have been exposed to water for 2 h, 6 h, 24 h and 48 h at a multiplicity of infection of 100. As control, H. pylori 26695 that were not exposed to water were used (Hp). cagA tyrosine phosphorylation levels were evaluated by western blot using an anti-PY99 antibody against tyrosine phosphorylated motifs and after membrane stripping, cagA was detected by re-probing with an anti-cagA antibody. Tubulin was used as equal protein loading control for co-cultures; B: protein lysates of H. pylori 26695 suspensions of each timepoint of water exposure were used as parallel controls of the amount of bacterial cagA and urease B proteins present. H. pylori 26695 that were not exposed to water (Hp) were also used as control.

While water-exposed H. pylori remained culturable for at least 6 h, cagA tyrosine phosphorylation was not observed in any of the co-cultures of water-exposed bacteria. After just 2 h in water, H. pylori were no longer able to translocate cagA into the host cells. This was not due to the lower cagA levels present in bacteria incubated in water (for at least 48 h) because water exposure affected neither the levels of cagA nor urease B, which remained similar to those of non-exposed H. pylori. These data suggest that water-exposed bacteria are not able to produce a functional cag T4SS and, consequently, are not able to translocate cagA into the host cells. In combination with our previous experiments, these results suggest that after being in water for periods longer than 6 h, H. pylori is still able to adhere to host cells, but is not effective in eliciting in vitro IL-8, a pro-inflammatory chemokine and apoptosis, possibly due to the non-functionality of the cag T4SS.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological evidence has pointed to environmental water as a risk factor for H. pylori infection among humans (Klein et al. 1991, Goodman et al. 1996, Karita et al. 2003). To elucidate if there are mechanisms that might allow water-exposed H. pylori to colonise the human stomach, several properties related to the survival and pathogenicity of H. pylori when exposed to water were studied. Our results showed that after being exposed to water for 24 h at 25ºC, H. pylori was no longer culturable. Studies have reported that when exposed to water, H. pylori enter a viable, but non-culturable state as a response to unfavourable environmental conditions (Azevedo et al. 2007a), which means that even though H. pylori cannot be recovered by plating techniques, bacterial cells might remain viable.

Adhesion is one of the most important pathogenic determinants of H. pylori because attachment to the host cells allows bacterial maintenance and gastric colonisation. Our results showed that water-exposed H. pylori has a decreased adhesion capacity compared to H. pylori that has not been in contact with water. Nevertheless, water-exposed bacteria still retain a significant adhesion capacity and this capacity does not significantly change with the time of water exposure. Our findings, in combination with the discovery that H. pylori would only grow under conditions mimicking the stomach if adhered to the surface of epithelial cells (Tan et al. 2009), could be a means for allowing H. pylori to remain in the host long enough for the occurrence of genetic recombination with other H. pylori strains that could be present in the same host, resulting in a higher genetic diversification (Azevedo et al. 2007b). This genetic diversification may help H. pylori adapt to a new host after transmission (Dorer et al. 2009).

Inflammation of the gastric mucosa is a universal consequence of H. pylori interaction with the host (Shimoyama & Crabtree 1998). Although water-exposed H. pylori still retained a considerable capacity to adhere to gastric cells, at 24 h of exposure, H. pylori was not able to influence IL-8 secretion. This is concurrent with the absence of nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation and the lack of IL-8 production in epithelial cells observed after the morphologic transition from bacillar into coccoid form, in which the H. pylori peptidoglycan structure is modified (Chaput et al. 2006). In our experiments, bacteria exposed to water for short time periods still triggered signalling that led to IL-8 production, which could represent bacteria with an unmodified peptidoglycan. Whether water exposure leads to altered peptidoglycan structure and to which extent these bacterial cell wall modifications allow these bacterial forms to temporarily escape detection by the host immune system remain to be elucidated.

Infection with H. pylori leads to increased host epithelial cell turnover with an increase in both apoptosis and proliferation rates (Peek et al. 1997, Moss et al. 2001, Cabral et al. 2006, 2007). Water-exposed bacteria were not able to induce alterations in the apoptotic index of host cells. As gastric epithelial cells have a rapid turnover, the lack of influence of water-exposed H. pylori on epithelial cell apoptosis may be an advantage for colonisation and persistence in the host. In addition, the lack of an ability to induce inflammation may also contribute to decreased host cell proliferation (Lynch et al. 1999), therefore slowing cell turnover.

Several lines of evidence have pointed to the importance of the cag T4SS in H. pylori-mediated host inflammation and apoptosis (Segal et al. 1999, Moss et al. 2001). In co-cultures of water-exposed H. pylori with gastric cells, we could not detect cagA phosphorylation, suggesting that the cag T4SS becomes non-functional. The absence of a functional T4SS may underlie the lack of influence of water-exposed H. pylori on host cell IL-8 secretion and apoptosis. It has been shown that activation of NF-κB leading to IL-8 secretion may not only be influenced by cagA (Brandt et al. 2005), but also stimulated by the T4SS itself. Indeed, it has been shown that H. pylori use the T4SS to deliver fragments of peptidoglycan that are sensed by the host nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain 1 receptor, resulting in NF-κB activation and IL-8 production (Viala et al. 2004). In animal models, H. pylori exposed to sterile tap water can colonise mice and induce gastric inflammation (She et al. 2003). However, further studies are needed to determine whether water-exposed H. pylori are still able to recover the functionality of the T4SS in vivo.

Our results show that water-exposed H. pylori retain adhesion properties while other interactions with the host cells are decreased. This may be beneficial for the bacterium in the sense that it may improve the likelihood of the establishment and persistence of the infection.

REFERENCES

- Adams BL, Bates TC, Oliver JD. Survival of Helicobacter pylori in a natural freshwater environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7462–7466. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7462-7466.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LP, Rasmussen L. Helicobacter pylori-coccoid forms and biofilm formation. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56:112–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo NF, Almeida C, Cerqueira L, Dias S, Keevil CW, Vieira MJ. Coccoid form of Helicobacter pylori as a morphological manifestation of cell adaptation to the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007a;73:3423–3427. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo NF, Guimarães N, Figueiredo C, Keevil CW, Vieira MJ. A new model for the transmission of Helicobacter pylori: role of environmental reservoirs as gene pools to increase strain diversity. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2007b;33:157–169. doi: 10.1080/10408410701451922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo NF, Huntington J, Goodman KJ. The epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2009;14(Suppl. 1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo NF, Pacheco AP, Vieira MJ, Keevil CW. Nutrient shock and incubation atmosphere influence recovery of culturable Helicobacter pylori from water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:490–493. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.490-493.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Selbach M. Role of type IV secretion in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1573–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:321–333. doi: 10.1172/JCI20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragança SM, Azevedo NF, Chaves L, Vieira MJ, Keevil CW, McBain A, Allison D, Brading M, Rickard A, Verran J, Walker J. Biofilms: the predominant bacterial phenotype in nature. Bioline; Cardiff: 2005. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in biofilms formed in a real drinking water distribution system using peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization; pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, Konig W, Backert S. NF-kappaB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori cagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:283–297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral MM, Mendes CM, Castro LP, Cartelle CT, Guerra J, Queiroz DM, Nogueira AM. Apoptosis in Helicobacter pylori gastritis is related to cagA status. Helicobacter. 2006;11:469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral MM, Oliveira CA, Mendes CM, Guerra J, Queiroz DM, Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Nogueira AM. Gastric epithelial cell proliferation and cagA status in Helicobacter pylori gastritis at different gastric sites. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:545–554. doi: 10.1080/00365520601014034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellini L, Allocati N, Angelucci D, Iezzi T, Di Campli E, Marzio L, Dainelli B. Coccoid Helicobacter pylori not culturable in vitro reverts in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput C, Ecobichon C, Cayet N, Girardin SE, Werts C, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Labigne A, Boneca IG. Role of amiA in the morphological transition of Helicobacter pylori and in immune escape. e97PLoS Pathog. 2006;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover TL, Krishna US, Israel DA, Peek RM., Jr Induction of gastric epithelial cell apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:951–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore MP, Sepulveda AR, El-Zimaity H, Yamaoka Y, Osato MS, Mototsugu K, Nieddu AM, Realdi G, Graham DY. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori from sheep-implications for transmission to humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1396–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorer MS, Talarico S, Salama NR. Helicobacter pylori’s unconventional role in health and disease. e1000544PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo C, Machado JC, Yamaoka Y. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan D, Rodgers M. A method to detect viable Helicobacter pylori bacteria in groundwater. Acta Hydrochim Hydrobiol. 2003;31:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Kato S, Kawamura T. Helicobacter pylori in Japanese river water and its prevalence in Japanese children. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;38:517–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Kato S, Watanabe A. Water source as a Helicobacter pylori transmission route: a 3-year follow-up study of Japanese children living in a unique district. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:909–910. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Kawamura T, Kato S, Tateno H, Watanabe A. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in cow’s milk. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2002;35:504–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman KJ, Correa P, Aux HJT, Ramirez H, DeLany JP, Pepinosa OG, Quinones ML, Parra TC. Helicobacter pylori infection in the Colombian Andes: a population-based study of transmission pathways. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:290–299. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karita M, Teramukai S, Matsumoto S. Risk of Helicobacter pylori transmission from drinking well water is higher than that from infected intrafamilial members in Japan. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1062–1067. doi: 10.1023/a:1023752326137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Farooqui A, Kazmi SU. Presence of Helicobacter pylori in drinking water of Karachi, Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:251–255. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Dore MP. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2005;10:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PD, Graham DY, Gaillour A, Opekun AR, Smith EO. Water source as risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection in Peruvian children. Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group. Lancet. 1991;337:1503–1506. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93196-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbiegel P, Lehmann I, Alfreider A, Fritz GJ, Boeckler D, Rolle-Kampczyk U, Richter M, Jorks S, Muller L, Richter MW, Herbarth O. Helicobacter pylori determination in non-municipal drinking water and epidemiological findings. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 2004;40:75–80. doi: 10.1080/10256010310001639868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusters JG, Gerrits MM, van Strijp JA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. Coccoid forms of Helicobacter pylori are the morphologic manifestation of cell death. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3672–3679. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3672-3679.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DA, Mapstone NP, Clarke AM, Jackson P, Moayyedi P, Dixon MF, Quirke P, Axon AT. Correlation between epithelial cell proliferation and histological grading in gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:367–371. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.5.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuckin MA, Every AL, Skene CD, Linden SK, Chionh YT, Swierczak A, McAuley J, Harbour S, Kaparakis M, Ferrero R, Sutton P. Muc1 mucin limits both Helicobacter pylori colonization of the murine gastric mucosa and associated gastritis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1210–1218. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss SF, Sordillo EM, Abdalla AM, Makarov V, Hanzely Z, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Holt PR. Increased gastric epithelial cell apoptosis associated with colonization with cagA + Helicobacter pylori strains. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1406–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori cagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SR, Mackay WG, Reid DC. Helicobacter sp. recovered from drinking water biofilm sampled from a water distribution system. Water Res. 2001;35:1624–1626. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek RM, Jr, Moss SF, Tham KT, Perez-Perez GI, Wang S, Miller GG, Atherton JC, Holt PR, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori cagA+ strains and dissociation of gastric epithelial cell proliferation from apoptosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:863–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.12.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz C, Hafsi N, Voland P. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors and the host immune response: implications for therapeutic vaccination. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz DM, Luzza F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2006;11(Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-405X.2006.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaei HG, Rahimi E, Zandi A, Rashidipour A. Helicobacter pylori as a zoonotic infection: the detection of H. pylori antigens in the milk and faeces of cows. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:184–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated cagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahamat M, Mai U, Paszkokolva C, Kessel M, Colwell RR. Use of autoradiography to assess viability of Helicobacter pylori in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1231–1235. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1231-1235.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She FF, Lin JY, Liu JY, Huang C, Su DH. Virulence of water-induced coccoid Helicobacter pylori and its experimental infection in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:516–520. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama T, Crabtree JE. Bacterial factors and immune pathogenesis in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1998;(43) Suppl. 1:S2–S5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Tompkins LS, Amieva MR. Helicobacter pylori usurps cell polarity to turn the cell surface into a replicative niche. e1000407PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG, Cardona A, Girardin SE, Moran AP, Athman R, Memet S, Huerre MR, Coyle AJ, DiStefano PS, Sansonetti PJ, Labigne A, Bertin J, Philpott DJ, Ferrero RL. NOD1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CL, Owen RJ, Said B, Lai S, Lee JV, Surman-Lee S, Nichols G. Detection of Helicobacter pylori by PCR, but not culture in water and biofilm samples from drinking water distribution systems in England. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:690–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]