Abstract

Background

Abacavir drug hypersensitivity in HIV-treated patients is associated with HLA-B*57:01 expression. To understand the immunochemistry of abacavir drug reactions, we investigated the effects of abacavir on HLA-B*57:01 epitope-binding in vitro and the quality and quantity of self-peptides presented by HLA-B*57:01 from abacavir-treated cells.

Design and methods

An HLA-B*57:01-specific epitope-binding assay was developed to test for effects of abacavir, didanosine or flucloxacillin on self-peptide binding. To examine whether abacavir alters the peptide repertoire in HLA-B*57:01, a B-cell line secreting soluble human leucocyte antigen (sHLA) was cultured in the presence or absence of abacavir, peptides were eluted from purified human leucocyte antigen (HLA), and the peptide epitopes comparatively mapped by mass spectroscopy to identify drug-unique peptides.

Results

Abacavir, but not didansosine or flucloxacillin, enhanced binding of the FITC-labeled self-peptide LF9 to HLA-B*57:01 in a dose-dependent manner. Endogenous peptides isolated from abacavir-treated HLA-B*57:01 B cells showed amino acid sequence differences compared with peptides from untreated cells. Novel drug-induced peptides lacked typical carboxyl (C) terminal amino acids characteristic of the HLA-B*57:01 peptide motif and instead contained predominantly isoleucine or leucine residues. Drug-induced peptides bind to soluble HLA-B*57:01 with high affinity that was not altered by abacavir addition.

Conclusion

Our results support a model of drug-induced autoimmunity in which abacavir alters the quantity and quality of self-peptide loading into HLA-B*57:01. Drug-induced loading of novel self-peptides into HLA, possibly by abacavir either altering the binding cleft or modifying the peptide-loading complex, generates an array of neo-antigen peptides that drive polyclonal T-cell autoimmune responses and multiorgan systemic toxicity.

Keywords: abacavir, antiretroviral therapy, autoimmunity, drug hypersensitivity, HIV, human leucocyte antigen, pharmocogenetics

Introduction

Therapeutic drugs are approved based on safety and efficacy in clinical trials. Although most drugs have favorable benefit–risk profiles, some treated individuals may still develop severe life-threatening side effects. Understanding the biochemical and immunological mechanisms mediating drug-induced hypersensitivity and severe adverse drug reactions is important for both treatment and prevention, as well as for identifying individuals at risk of developing adverse reactions before therapy. A number of immune-mediated or idiosyncratic drug reactions have been genetically linked with specific human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class I and class II alleles. Drug hypersensitivity to abacavir [1–3] is linked to HLA-B*57:01. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions associated with class I HLA are seen with carbamazepine (CBZ) in some individuals expressing HLA-B*15:02 [4], B*15:11 [5], A*31:01 [6] and with allopurinol in HLA-B*58:01 [7]. Flucloxacillin causes drug-induced liver injury in patients expressing HLA-B*57:01 [8].

Clinical syndromes of HLA-associated drug reactions vary widely depending on the severity of reactions and the target tissue/organ. Abacavir hypersensitivity involves multiple organ systems and within 1–2 weeks of initial treatment patients experience rash, fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fatigue and in some cases respiratory symptoms. Overall, symptoms resemble graft-versus-host disease. Symptoms usually resolve with discontinuation of abacavir; however, re-exposure or re-challenge results in rapid, severe and life-threatening reactions.

Molecular mechanisms for HLA-associated drug reactions have not been clearly established. Several models (for review [9,10]) have been presented that include: 1) hapten/prohapten mechanisms in which drugs or drug-metabolites can covalently or noncovalently bind to self proteins, peptides or HLA, thereby creating neo-antigens that are then processed and loaded into HLA molecules for presentation and activation of T cells, and 2) direct pharmacologic reversible interactions of drugs with immune receptors, called the p-i model [11], in which drugs such as CBZ [12] and sulfamethoxazole bind noncovalently to T-cell receptors or HLA–peptide complexes stimulating T cells. Moreover, it is believed that drugs may also cause tissue damage and inflammation providing cofactors/co-stimulation that facilitates immune cell activation [13]. Abacavir hypersensitivity may be driven by a hapten/prohapten-related mechanism as CD8+ T-cell responses require transporter of antigen presentation (TAP)/tapasin expression, antigen processing and specific amino acids in the F pocket of HLA-B*57:01 for presentation to drug-specific T cells to stimulate polyclonal responses [14]. In-silico models suggest that abacavir could interact with the F pocket of HLA-B*57:01 in the absence of peptide [15].

In this report, we tested abacavir by applying an in-vitro B*57:01 peptide-binding assay and examined the endogenous peptide repertoire presented by HLA-B*57:01 from abacavir-treated versus untreated cells using proteomic techniques. Here, we report that abacavir has dramatic effects on the quantity and quality of self-peptide loading to HLA-B*57:01 by possibly providing a pseudo-anchor position in HLA favoring neo-antigens in HLA or by modifying the peptide-loading complex (PLC). Abacavir hypersensitivity therefore may result from this novel molecular mechanism, which drives autoimmune polyclonal T-cell responses.

Methods

Reagents

Abacavir sulfate was obtained from GSK (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) and Santa Cruz Biochemicals (Santa Cruz, California, USA), flucloxacillin from Apotex (UK), and didanosine from Bristol Myer Squibb (Princeton, New Jersey, USA). Synthetic peptides were made and purified to 98% purity by Peptide2.0 (Manassas, Virginia, USA).

Peptide-binding assay

To assess the ability of synthetically defined peptide epitopes to associate with HLA-B*5701, an assay based on inhibition of binding of the fluorescent standard peptide LF9FITC [LSSPVT(K-FITC)KSF] was developed as previously published [16,17]. Binding events were determined using fluorescence polarization. The assay was slightly modified for measuring drug interactions by replacing the addition of competitor peptides with the drug of interest.

Cell lines and transfectants

Soluble HLA-B*57:01 molecules are a trimeric complex consisting of a heavy chain comprised of α1, α2 and α3 domains, a light chain (β2m) and the peptide. The heavy chains of the sHLA class I molecules are truncated just before the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic domain [18]. The mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 carrying the sHLA-B*57:01 construct was used to express HLA-B*57:01 proteins in the class I negative Epstein Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line 721.221.

HLA peptide isolation

Soluble HLA-B*57:01 transfectants were cultured to a high density in a hollow fiber bioreactor. After milligram quantities of sHLA were collected under nontreated conditions, abacavir (10μg/ml) was then added to the culture. Harvested proteins were purified using affinity chromatography. Peptides were released from the HLA complex by addition of 10% acetic acid under boiling conditions and separated from heavy chains and β2m by passing them through a 3-kDa cut-off membrane filter (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). Drug-treated and nontreated peptide pools were separated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and fractions were collected. Ultra-violet absorbance was monitored at 215 nm. Consecutive and identical peptide separations were performed for drug-treated and untreated B*57:01 peptide batches (see Supplement 1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A228)

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

Peptide fractions 50, 60 and 70 obtained from reverse-phase HPLC separations were analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC–MS) as described in Supplement 1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A228.

Results

Abacavir enhances epitope binding to HLA-B*57:01

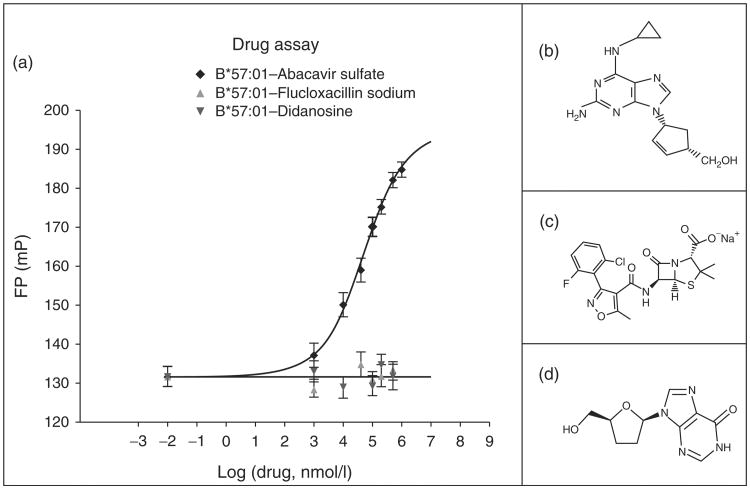

To evaluate effects of abacavir on HLA-peptide interactions, a specific peptide-binding assay for HLA-B*57:01 was designed based on fluorescence polarization utilizing the FITC-labeled tracer peptide LF9FITC [LSSPVT(K-FITC)KSF]. To test the feasibility of binding, competition of the unlabeled LF9 peptide against its labeled counterpart was shown (Fig. 1). The unlabeled LF9 peptide was titrated in eight serial dilutions (10 nmol/l to 80 μmol/l) and a log IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) value of 2.6 was determined, which is consistent with high-affinity binding [16,17]. Abacavir was then tested in this assay over a 2 log range of concentrations and compared with didanosine, a related nucleoside analogue, and flucloxacillin, an antibiotic associated with liver injury in individuals bearing HLA-B*57:01 (Fig. 2a). Abacavir, in contrast to didanosine and flucloxacillin, increased LF9FITC peptide binding in a dose-dependent manner, with effects starting at 10 μmol/l and an overall half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 52 μmol/l. In addition, the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) in patients from clinical trial is between 10 and 15 μmol/l (Ziagen package insert), overlapping with concentrations that enhance epitope binding in vitro. These findings suggest that abacavir might have a direct effect on the structure of HLA possibly by binding to the cleft to allow better access or more stable interactions of self-peptides with the HLA peptide-binding site.

Fig. 1. Fluorescence polarization-based HLA-B*57:01 competition assay.

Soluble HLA B*57:01 was derived from 721.221 B-cell transfectants and affinity purified before use in binding assays. The tracer is the self-peptide LF9 (LSSPVTKSF) from IgKappa substituted with a FITC-lysine residue at P6 that is not involved with direct HLA binding based on examination of the crystal structure [14]. Serial dilutions of nonlabeled LF9 competitor were incubated with a constant concentration of heat activated sHLA-B*57:01, excess β2m and the FITC-labeled tracer peptides until equilibrium was reached by monitoring changes in fluorescent polarization (FP) on an Analyst AD plate reader (Molecular Devices Sunnyvale, California, USA). The IC50 concentration of unlabeled competitor that produces FITC-labeled peptide binding half way between the upper and lower plateau is indicated.

Fig. 2. (a) Effect of abacavir sulfate, didanosine and flucloxacillin sodium on LF9FITC binding to sHLA-B*57:01.

Structures for drugs are shown in (b) abacavir, (c) flucloxacillin and (d) didanosine. To monitor drug effects on peptide binding, abacavir, didanosine or flucloxacillin were added over a wide concentration range and fluorescent polarization (FP) measured at equilibrium. The increase in FP represents an increase in epitope binding to HLA.

Abacavir treatment induces loading of unique self-peptides into HLA-B*57:01

The preceding results demonstrated that abacavir can increase self-epitope binding, suggesting that drug may alter quantitative and qualitative loading of self-peptides to HLA-B*57:01 in abacavir-treated cells. To characterize the effect of abacavir on the intracellular loading of endogenous peptide ligands, a 721.221 B-cell line producing sHLA-B*57:01 was cultured with and without abacavir and sHLA collected from the bioreactor outputs. Soluble HLAwas affinity purified, peptides stripped and separated by preparative HPLC. Three of the matched HPLC fractions were then analyzed by LC–MS. The most abundant ions were compared between untreated and drug-treated samples and unique ions not present in controls were targeted for mass spectrometry (MS) fragmentation. A number of sequence matches were found among unique and common peptides as listed in Table 1. Two examples of MS–MS fragmentation for drug unique ions are shown Fig. 3a, HSLPALIQI, and Fig. 3b, STIRLLTSL.

Table 1. HLA-B*57:01 common and abacavir-induced unique peptides in HPLC fractions 50, 60 and 70.

| Sequence | Fraction | Score | Measured m/z (z) | MH+ matched | Error (ppm) | Accession number | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abacavir-induced unique peptides (C-terminus with I/L) | |||||||

| GTITGVDVSm | 50 | 10.82 | 498.2409 (2) | 979.476 | 3.1 | P62314 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein SM D1 |

| KSVDPENNPTL | 50 | 7.49 | 607.3080 (2) | 1213.606 | 2.3 | Q9Y5L0 | Transportin-3 |

| TAGAHRLW | 60 | 19.39 | 456.2471 (2) | 911.485 | 2.5 | O00767 | Acyl-CoA desaturase |

| ASSSQITHI | 60 | 13.75 | 478.2650 (2) | 955.521 | 2.1 | Q6PL18 | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 2 AAA domain-containing protein |

| NTVELRVKI | 60 | 13.18 | 357.8901 (3) | 1071.652 | 3.4 | P04844 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 |

| STSDIITRI | 60 | 12.73 | 503.2833 (2) | 1005.558 | 1.8 | P49585 | Choline-phosphate cytidylyltansferase A |

| IVKnKPVEL | 60 | 11.90 | 520.8219 (2) | 1039.651 | 1.4 | Q8IZJ1 | Netrin receptor UNC5B |

| RTFETIVKQQI | 60 | 9.79 | 454.9306 (3) | 1362.774 | 2.4 | P20591 | Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 |

| GTINIVHPKL | 60 | 9.79 | 364.5581 (3) | 1091.657 | 2.4 | Q9Y617 | Phosphoserine aminotransferase |

| LSTDVAKTL | 60 | 8.35 | 474.2748 (2) | 947.541 | 1.6 | Q03001 | Bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 |

| GTAPVNLNI | 60 | 8.14 | 449.7539 (2) | 898.499 | 1.4 | Q6UN15 | Pre mRNA 3′-end-processing factor FIP1 |

| KTIEDDLVSAL | 70 | 10.16 | 602.3281 (2) | 1203.647 | 1.8 | Q9Y606 | tRNA pseudouridine synthase A, mitochondrial |

| ASITPGTILI | 70 | 10.03 | 493.3010 (2) | 985.593 | 1.9 | Q02878 | 60S ribosomal protein L6 |

| STIRLLTSL | 70 | 9.54 | 502.3111 (2) | 1003.615 | 0.3 | P49368 | T-complex protein 1 subunit gamma |

| LHLLVIR | 70 | 9.09 | 432.2954 (2) | 863.582 | 1.1 | Q9Y4F4 | Protein FAM179B |

| HSLPALIQI | 70 | 6.37 | 496.3015 (2) | 991.593 | 2.2 | Q8N8D1 | Programmed cell death protein 7 |

| Common peptides (C-terminus with F, W, Y) | |||||||

| IAVKVNHSY | 50 | 19.21 | 344.1951 (3) | 1030.568 | 2.7 | Q8N2W9 | E3 SUMO-protein ligase PIAS4 |

| YVPEDEDLK | 50 | 17.88 | 554.2660 (2) | 1107.520 | 3.9 | Q8WUD4 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 12 |

| VTAIEDRQY | 50 | 15.43 | 547.7791 (2) | 1094.548 | 3.0 | Q99873 | Protein arginin N-methytransferase 1 |

| VTKTVSNDSF | 50 | 14.42 | 549.2785 (2) | 1097.547 | 2.2 | P55209 | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 |

| ISQPASGNTF | 50 | 13.24 | 511.2522 (2) | 1021.495 | 2.2 | Q14157 | Ubiquitin-associated protein2-like |

| ITAGAHRLW | 60 | 21.68 | 342.1937 (3) | 1024.569 | −2.1 | O00767 | Acyl-CoA desaturase |

| VAKVGQYTF | 60 | 18.65 | 506.7774 (2) | 1012.546 | 1.3 | Q86Y39 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 11 |

| VTYKNVPNW | 60 | 18.31 | 560.7940 (2) | 1120.579 | 1.9 | P62826 | GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran |

| TVYPKPEEW | 60 | 17.03 | 574.7867 (2) | 1148.562 | 3.4 | P19387 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 |

| KTVTAMDVVY | 60 | 11.15 | 563.7952 (2) | 1126.581 | 1.6 | P62805 | Histone H4 |

| HAIPLRSSW | 60 | 10.66 | 533.7942 (2) | 1066.579 | 1.8 | P62873 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta-1 |

| KTVTAmDVVY | 60 | 10.00 | 571.7925 (2) | 1126.581 | 1.6 | P62805 | Histone H4 |

| LSAFLPARF | 70 | 13.39 | 511.2965 (2) | 1021.583 | 2.7 | Q9NUQ2 | 1-Acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase ε |

A, alanine; F, phenylalanine; I, isoleucine; L, leucine; m, oxidized methionine; n: deamidation; S, serine; T, threonine; W, tryptophan; Y, tyrosine. HLA-B*57:01 peptide motif: P2-(A,T,S), P9-carboxy terminus (F, W, Y).

Fig. 3. Examples of MS–MS fragmentation spectrums from abacavir-unique peptides from fraction 70.

(a) Peptide molecular weight (MW) 990.5868 HSLPALIQI. (b) Abacavir-unique peptide MW 1002.6061 STIRLLTSL.

Overall, peptides common to both untreated and treated cells exhibited canonical P2 and C-terminal anchor motifs for B*57:01 including alanine, threonine or serine at the P2 position, and a C-terminal tryptophan, tyrosine or phenylalanine [19,20]. In contrast, peptides unique to the drug-treated samples were biased at the C-terminus showing a high preference for isoleucine or leucine rather than tryptophan, tyrosine or phenylalanine. This C-terminal impact of drug treatment did not extend to the P2 anchor; amino acids consistent with the B*57:01 motif (alanine, threonine or serine) were observed. A diverse set of drug-induced peptides from a variety of cellular proteins were identified including a sequence from a protein highly expressed in skin, the autoimmune target Bullous pemphigoid antigen 1, also called dystonin. As mentioned above, most unique peptides in drug-treated samples had isoleucine or leucine at the C-terminus, but we identified a sequence containing a C-terminal tryptophan and alanine in P2. This peptide, TAGAHRLW, from a desaturase found also in liver, was 8 amino acids in length. Interestingly, the same sequence with an additional isoleucine at the N-terminus, ITAGAHRLW, was present in both untreated and treated cells. Other peptides of interest from this set included the interferon-induced GTP-binding protein MX-1.

Binding of novel drug-induced peptides to HLA-B*57:01

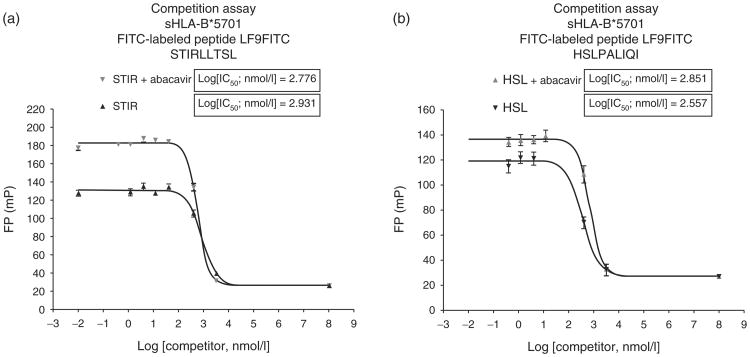

The appearance of unique peptides in cells treated with drug which were not present in untreated cells suggested that these peptides may not bind to sHLA-B*57:01, and possibly require the presence of abacavir to be integrated into the complex. Several drug-induced peptides were synthesized and then tested for binding to sHLA-B*57:01 in the binding assay. As reference, two drug-induced peptides, HSLPALIQI and STIRLLTSL, that contain isoleucine/leucine at the C-terminus could strongly compete in the HLA-B*57:01 peptide-binding assay (Fig. 4a and b), with logIC50 values consistent with high-affinity binding. Addition of abacavir did not substantially shift the IC50 of the drug-induced peptides, thus showing no dramatic change in the affinity of the peptide for sHLA-B*57:01, indicating that once folded, sHLA might provide a higher affinity for these peptides than in the intracellular PLC.

Fig. 4. Competitive binding evaluation of HLA-B*57:01 drug-induced peptides.

(a) STIRLLTSL and (b) HSLPALIQI with and without abacavir. IC50 values for two DI peptides were determined applying serial dilutions of nonlabeled HSL and STIR competitor, respectively, in the presence and absence of 200 μmol/l of abacavir. Results showed the expected increase in reference LF9FITC peptide binding signal with abacavir. No significant difference in inhibition between experiments in both cases could be observed. DI, drug-induced

Discussion

We report here that abacavir enhances peptide binding in sHLA-B*57:01-specific assays and induces loading of novel self-peptides into sHLA-B*57:01 expressing cells treated with drug. Novel drug-induced peptides carried distinct changes in the HLA-binding motif characteristic of sHLA-B*57:01 epitopes, consisting of isoleucine or leucine at the C-terminus, instead of the consensus F-pocket binding amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine or tyrosine). Drug-induced peptides bind with high affinity to monomeric sHLA-B*57:01 in the absence of drug, and abacavir does not change their IC50. These results support a model of drug-induced autoimmunity in which drugs can alter the quality and quantity of the endogenous peptide repertoire in HLA to generate neo-antigens and drive polyclonal T-cell responses to self-epitopes.

Abacavir-induced autoimmunity helps to explain the multiorgan systemic hypersensitivity reactions in which drug-induced peptides would be expressed on HLA in many tissues, including skin and the gastrointestinal system, to drive T-cell expansion and serve as targets for CD8+ effector cells. Once drug is discontinued, drug-induced peptides would disappear, reactive T-cell pools would contract and differentiate to T memory cells. Re-exposure to abacavir would again generate drug-induced peptides in antigen presenting cells (APCs) and tissues leading to rapid expansion of T memory cells and effectors to cause severe and in some cases life-threatening reactions.

Our data indicate that drug hypersensitivity to abacavir may involve two processes. Abacavir, but not didanosine and flucloxacillin, enhanced binding of the self-peptide ligand (LF9) carrying a consensus motif (C-terminal-phenylalanine, phenylalanine) for HLA-B*57:01, in a dose-dependent manner which did not require drug metabolism. The half-maximal effective concentration of abacavir was 52 μmol/l, which seems to suggest a low-affinity binding interaction. Although flucloxacillin is associated with liver toxicity in HLA-B*57:01 individuals, it may require metabolism to form a reactive intermediate to bind protein or HLA. Metabolites of abacavir created by alcohol dehydrogenase [21] may have a similar activity to enhance peptide binding and have potential to create covalent protein adducts. Direct effects of abacavir on binding suggest that the drug could alter the structure of HLA to affect peptide binding in the HLA cleft, including the possibility that abacavir remains stably bound to HLA and peptide in the complex. If abacavir remains in the complex, peptides with HLA-B*57:01 consensus motifs could adopt conformations that are different in the presence of drug compared with peptide in HLA alone and be recognized as neo-antigens by T cells. Functionally, it is feasible that increased peptide binding to HLA-B*57:01 of epitopes with consensus-matching motifs could break tolerance if other co-stimulatory or inflammatory cofactors are present. Alternatively, as supported by our peptide analysis, the presence of abacavir during peptide loading may substantially change the structure of the peptide receptive HLA-B*57:01 groove in the PLC, fostering distinct peptide requirements for high-affinity binding. Structural studies are required to address conformations of peptides and abacavir in HLA-B*57:01.

The second molecular process, probably related to the first, is the ability of drug to promote loading of a distinct repertoire of self-peptides in HLA-B*57:01 in cells. These neo-peptides range in length from 9 to 11 amino acids and lack the C-terminal amino acids tryptophan, phenylalanine or tyrosine, characteristic of HLA-B*57:01 motifs that interact with the phenylalanine pocket [19]. Instead, most of the novel peptides contain aliphatic isoleucine/leucine at the C-terminus, and have the preferred, canonical amino acids in the P2 position [19]. We believe the small set of peptides identified here are representative of a larger number of drug unique peptides carrying unusual C-terminal amino acids, along with other self-peptides with correct HLA-B*57:01 motifs that are enhanced by abacavir. In addition, if abacavir is metabolized to form protein adducts then haptenized peptides could also be presented in HLA. However, we have not, as yet, identified covalent drug–peptide adducts in the peptide fractions. Of note, HLA-B*57:01 epitopes with C-terminal isoleucine/leucine or Valine have been reported from a variety of microorganisms [20,22], although not as endogenous peptides from human proteins. Another study examining HLA-bound peptides from CBZ-treated cells expressing HLA-B*15:02 did not find differences in the peptide repertoire from drug-treated cells compared with control cells [23].

Unexpectedly, drug-induced peptides bind to sHLA with high affinity and addition of abacavir did not modify their IC50 values. Therefore, drug-induced peptides are capable of binding HLA-B*57:01, but either have a low affinity during in vivo loading or have limited access to the PLC in cells. Abacavir may provide a noncovalent hydrophobic anchor substitute during loading in the PLC by bridging between the C-terminal aliphatic isoleucine/leucine and the F-pocket amino acids such as serine-116 or aspartic acid-114, thereby stabilizing the neo-epitope. Abacavir may also modify tapasin or TAP interactions in the PLC [24] to allow drug-induced peptide binding where normally these peptides are excluded. TAP/tapasin and antigen processing are required for presentation of abacavir to CD8+ T cells and drug presentation maps to HLA amino acid serine-116 [14]. By this mechanism, abacavir would not be required to remain in a complex with HLA and peptide after loading, and therefore might contribute transiently to peptide binding in vivo. Binding of drug-induced peptides to recombinant sHLA-B*57:01 in vitro without drug would be compatible with this model, suggesting that the folded conformation of the sHLA in the binding assay provides a higher affinity pocket than the peptide receptive conformation of the cleft in the PLC. It is possible that with some peptides, abacavir may remain in the HLA complex. Alternatively, abacavir could also impact peptide repertoires by modifying other steps in peptide processing, delivery and loading. Further biochemical and structural studies are needed to define abacavir interactions with HLA.

Our data support a model of drug-induced autoimmunity as a consequence of abacavir exposure. Peptides with isoleucine/leucine in the C-terminus may not bind strongly to HLA-B*57:01 in vivo and therefore be absent during thymus development. Thus, T-cell clones recognizing peptide epitopes with these characteristics would not go through clonal deletion. Upon drug exposure, drug-induced peptides and some peptides with consensus motifs will be loaded into HLA. This generates neo-antigens and stimulates naive T cells to undergo a primary immune response, and possibly activates some cross-reactive memory T cells. Initial responses to drug-induced peptides may occur in lymphoid tissues either by direct presentation by resident antigen-presenting cells or by Langerhans cells migrating from skin or from other tissues. Novel self-peptide presentation along with co-stimulation would promote activation and expansion and then migration of effector T cells to tissues where antigens and drugs are present in high amounts, such as skin. Interestingly, we identified a peptide from Bullous pemphigoid antigen 1/dystonin that is present in skin and could be a potential target for autoimmunity. Presumably, many other self-antigens could be targeted by similar mechanisms. For drugs that induce liver injury with HLA associations, T cells similarly could be generated centrally in lymphoid tissue and migrate to liver to attack cells with drug-dependent or metabolite-dependent liver-specific epitopes. Discontinuation of drug therapy would remove the source of self-peptides in HLA in APCs and in tissues and curtail T-cell autoreactivity.

Furthermore, we identified a peptide corresponding to the interferon-inducible protein, MX1. HIV infection is associated with high levels of interferon. In these circumstances, and in the presence of abacavir, cells responding to interferon may become targets for autoimmune T-cell recognition. Further experiments are required to verify that drug-induced peptides are recognized by T cells from abacavir-hypersensitive patients.

Many HLA-B*57:01 individuals are able to tolerate abacavir and not show hypersensitivity (1), thus it is clear that HLA-B*57:01 is required but not sufficient for drug hypersensitivity, supporting a role for additional host cofactors or inflammatory stimuli. In the absence of co-stimulation, T cells may become or remain tolerant to drug-induced peptides. Cofactors could include direct drug innate effects or tissue damage causing secondary inflammation, or infection such as by HIV itself in the case of abacavir. Alternatively, tolerant patients may have been previously exposed to drug-induced peptides centrally in the thymus leading to T-cell deletion or peripherally to anergize T cells. Another mechanism could involve suppressor activities of T regulatory cells on the auto-reactive T cells.

The effect of abacavir on HLA loading of novel self-peptides with potential to drive autoimmunity may represent a model of drug hypersensitivity for other drugs with genetic associations with HLA. Analysis of drug interactions with other alleles and drug combinations examining HLA peptide binding along with molecular approaches to identify unique epitopes in HLA induced by drug exposure will help to unravel molecular mechanisms and targets for drug reactions. These methods may also help to predict novel HLA linkages for new drugs to prevent potential unforeseen toxicities. Furthermore, we suggest that altered loading of novel self-peptides with modifications in HLA-anchor motifs through perturbations in the PLC may occur not only as a consequence of drug exposure but also as a process that contributes to some autoimmune disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Montserrat Puig for critical reading and editorial advice on the manuscript.

The work was supported by the FDA intramural research program. D.H.M. is supported by the intramural research program of the NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.L and M.T.B. developed the mass spectrometric methods and performed the MS data analysis. C.M. and S.V. performed and W.H.H. supervised sHLA production, peptide purification and preliminary MS analysis. L.L. expressed and purified sHLA proteins and performed HLA-binding assays. M.G., A.D.R. performed and R.B developed, supervised and performed the HLA peptide/competition binding assays.

M.A.N., R.B., M.T.B. and W.H.H. conceived, planned, supervised and analyzed experimental data. D.H.M. and J.W. were involved in the conception, planning and review of data. M.A.N. wrote the first draft of the paper and M.T. B., D.H.M., W.H.H. and R.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript to the final version.

Author's statement: All authors have read the manuscript as submitted to AIDS and have approved the content of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina JM, Workman C, et al. HLA-B*57:01 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallal S, Nolan D, Witt C, Masel G, Martin AM, Moore C, et al. Association between presence of HLA-B*5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:727–732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hetherington S, Hughes AR, Mosteller M, Shortino D, Baker KL, Spreen W, et al. Genetic variations in HLA-B*region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir. Lancet. 2002;359:1121–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, Ho HC, et al. Medical genetics: a marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature. 2004;428:486. doi: 10.1038/428486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Aihara M, Matsunaga K, Tohkin M, Kurose K, et al. HLA-B*1511 is a risk factor for carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japanese patients. Epilepsia. 2010;51:2461–2465. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormack M, Alfirevic A, Bourgeois S, Farrell JJ, Kasperavičiūtė D, Carrington M, et al. HLA-A*3101 and carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions in Europeans. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1134–1143. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4134–4139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly AK, Donaldson PT, Bhatnagar P, Shen Y, Pe'er I, et al. HLA-B*57:01 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin. Nat Genet. 2009;41:816–819. doi: 10.1038/ng.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adam J, Pichler WJ, Yerly D. Delayed drug hypersensitivity: models of T-cell stimulation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:701–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bharadwaj M, Illing P, Theodossis A, Purcell AW, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Drug hypersensitivity and human leukocyte antigens of the major histocompatibility complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:401–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichler WJ. Pharmacological interaction of drugs with antigen-specific immune receptors: the p-i concept. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:301–305. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei CY, Chung WH, Huang HW, Chen YT, Hung SI. Direct interaction between HLA-B*and carbamazepine activates T-cells in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.990. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Uetrecht JP. The danger hypothesis applied to idiosyncratic drug reactions. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010;196:493–509. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00663-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chessman D, Kostenko L, Lethborg T, Purcell AW, Williamson NA, et al. Human leukocyte antigen class I-restricted activation of CD8+ T-cells provides the immunogenetic basis of a systemic drug hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2008;28:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Chen J, He L. Harvesting candidate genes responsible for serious adverse drug reactions from a chemical-protein interactome. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchli R, VanGundy RS, Giberson CF, Hildebrand WH. Development and validation of a competition-based peptide binding assay for HLA A*0201 using fluorescence polarization: a new screening tool for epitope discovery. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12491–12507. doi: 10.1021/bi050255v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchli R, VanGundy RS, Hickman-Miller HD, Giberson CF, Bardet W, Hildebrand WH. Real-time measurements of in vitro peptide binding to HLA-A*0201 by fluorescence polarization. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14852–14863. doi: 10.1021/bi048580q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prilliman K, Lindsey M, Zuo Y, Jackson KW, Zhang Y, Hildebrand W. Large-scale production of class I bound peptides: assigning a signature to HLA-B*1501. Immunogenetics. 1997;45:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s002510050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber LD, Percival L, Arnett KL, Gumperz JE, Chen L, Parham P. Polymorphism in the alpha 1 helix of the HLA-B heavy chain can have an overriding influence on peptide-binding specificity. J Immunol. 1997;158:1660–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. www.syfpeithi.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh JS, Reese MJ, Thurmond LM. The metabolic activation of abacavir by human liver cytosol and expressed human alcohol dehydrogenase isozymes. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;142:135–154. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vita R, Zarebski L, Greenbaum JA, Emami H, Hoof I, Salimi N, et al. The immune epitope database 2.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D854–D862. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang CWO, Hung SI, Juo CG, Lin YP, Fang WH, et al. HLA-B 1502-bound peptides: implications for the pathogenesis of carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. The quality control of MHC class I peptide loading. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;206:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.