INTRODUCTION

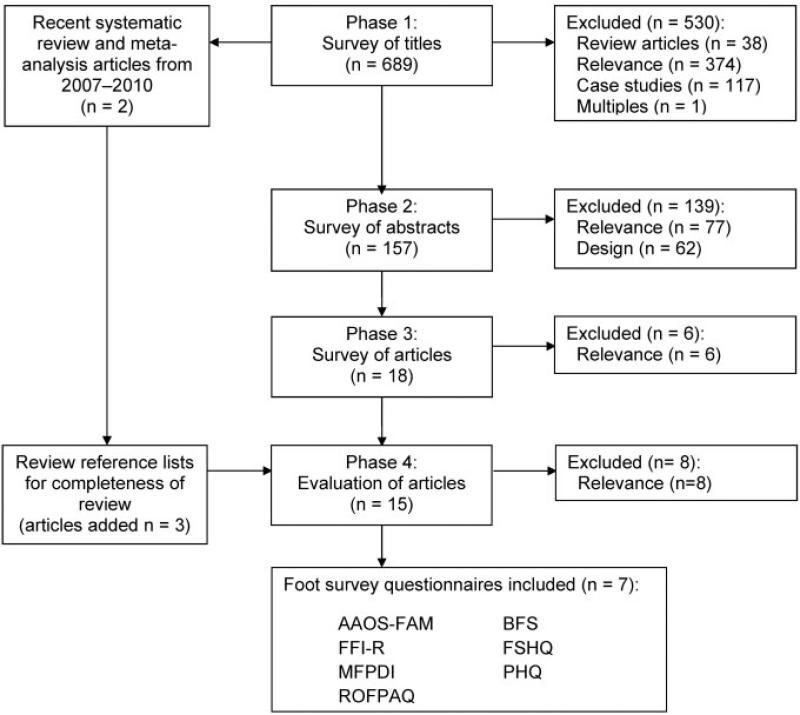

The foot is one of the most complex, yet understudied musculoskeletal systems in the body. However, with the growing interest in foot health in rheumatology and because of its pivotal role in gait and posture, researchers and clinicians have developed a number of surveys and assessments for measuring foot health and its impact on quality of life. This systematic review will focus on questionnaires and surveys for patient/participant perception of foot health and its impact on quality of life, commonly referred to as patient-reported outcome measures. The system we employed to determine the patient-reported outcome measures included in this review is provided as a flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Identification of studies for inclusion in the review. AAOS-FAM = American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Lower Limb Outcomes Assessment: Foot and Ankle Module; BFS = Bristol Foot Score; FFI-R = Revised Foot Function Index; FHSQ = Foot Health Status Questionnaire; MFPDI = Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index; PHQ = Podiatric Health Questionnaire; ROFPAQ = Rowan Foot Pain Assessment.

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ORTHOPEDIC SURGEONS LOWER LIMB OUTCOMES ASSESSMENT: FOOT AND ANKLE MODULE (AAOS-FAM)

Description

Purpose

To evaluate patient perception of foot health and to measure surgical outcomes (1).

Content

Questions regarding foot and ankle health from patient's perspective (1). There are 5 subscales: pain (9 questions), function (6 questions), stiffness and swelling (2 questions), giving way (3 questions), and shoe comfort (5 questions).

Number of items

25 questions.

Response options/scale

Respondents are asked to answer on a scale of 1–5 or 1–6 with 1 being the best outcome and 5 or 6 the worst.

Recall period for items

1 week.

Endorsements

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Examples of use

Primarily administered to patients receiving treatment for musculoskeletal problems of the foot and ankle.

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available on the AAOS web site at URL: http://www.aaos.org/research/outcomes/outcomes_lower. asp.

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

Scoring spreadsheet and instructions are available with the assessment. Scores are standardized to a percentage (0–100) score and then transformed on normative scale. Scoring is automated on available worksheet.

Score interpretation

A lower normative score indicates worse foot health relative to the population (2). Scores range from 0–100 for each subscale and can be placed on a normative scale from –26 to 56 based on the general population (1,2). The mean ± SD population score for the global foot and ankle module is 93.19 ± 12.33 (n = 1,755) (2).

Respondent burden

Not reported.

Administrative burden

Training consists of self-study of the scoring documentation (see URL: http://www.aaos.org/research/outcomes/outcomes_lower.asp).

Translations/adaptations

Full assessment is split into several submodules that include questionnaires evaluating the lower-extremity core, foot and ankle, hip and knee, sports-related injuries, and common knee problems (1).

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Content was developed and refined with input from clinician focus groups (1).

Acceptability

Not reported.

Reliability

Internal Cronbach's alpha of 0.91, 0.83, 0.61, and 0.88 was reported for the pain, function, stiffness, and giving way subscales, respectively, and 0.93 for the entire foot and ankle module. With the exception of the stiffness subscale, these indicate generally good internal reliability. The module had a test–retest reliability measured internally as 0.79, and subscale test–retest reliability of 0.87, 0.81, 0.99, and 0.81 for the pain, function, stiffness, and giving way subscales, respectively (1). In an independent study of reliability, Hunsaker et al (2) reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.81–0.96 for all lower-extremity core (foot and ankle, hip and knee, sports-related injuries, and common knee problems, respectively) without noting the individual subscale values. Their reported test– retest reliability was 0.79 for the foot and ankle module (2).

Validity

The questionnaire was validated by comparison with clinical assessments performed by a trained physician, and correlations between the questionnaire and physician scores of pain (r = 0.49) and function (r = 0.43) were observed. Patient responses were also seen to be strongly correlated with Short Form 36 (SF-36) scores (r = 0.65) and assessment of the lower-extremity core (r = 0.89) (1).

Ability to detect change

No data have been reported on the ability of the global foot and ankle modules to detect change; however, overall lower-extremity scores were shown to correlate (r = 0.54) with changes in physician-assessed function scores indicating responsiveness to change (1).

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

AAOS-FAM is one of the few foot patient-reported outcome measures that have internal and external reliability measures.

Caveats and cautions

This questionnaire does not evaluate the impact of foot health with regard to its impact on the participant's psychological state, social activities, or self-esteem, all of which may influence quality of life and patient satisfaction (3).

Clinical usability

This survey was designed for orthopedists and health care professionals to validate and compare results and clinical outcomes across studies (4). As the AAOS-FAM is clinical in nature, few questions address quality of life; however, by combining the AAOSFAM with the SF-36, the 2 instruments can be a means for evaluating foot health–related quality of life (1). Further, the AAOS-FAM, similar to several other foot-related patient-reported outcome measures, lacks an independent review of the validity and lacks information regarding the minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference, which limits its clinical usability.

Research usability

Most studies that have used the AAOS-FAM have focused on outcomes assessment concerning treatment of a particular condition (e.g., clubfoot [5]) or of surgical method (e.g., Ilizarov method for tibial nonunions [6]). However, because it was designed to measure clinical assessments, its usability for assessing population-level or community-based foot and ankle health appears limited.

BRISTOL FOOT SCORE (BFS)

Description

Purpose

To assess the patient's perception of the impact of foot problems on everyday life (7).

Content

Questions relating to foot pain and concern, footwear and general foot health, and mobility. There are 3 subscales: foot concern and pain (7 questions), footwear and general foot health (4 questions), and mobility (3 questions) (7). Fourteen of the 15 questions are scored; the final question is a statement of general health, which does not add into the BFS.

Number of items

15 questions.

Response options/scale

Each response option is assigned a score of 1 (best possible situation) to 3–6 (worst possible situation, number dependent on number of response options available) for each BFS survey question (7).

Recall period for items

2 weeks.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

Target population is podiatric patients, and it has been used to study effects of nail fungus treatment (8) and foot surgery (9).

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available in the original article (7).

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

Scores for each question are summed per a provided scoring guide. Scores range from 15 (best possible situation) to 73 (worst possible situation). Within the subscales, foot concern and pain scores range from 7–36, footwear and general foot health scores range from 4–20, and mobility scores range from 3–12.

Score interpretation

Lower scores indicate that the patient perceives fewer foot problems.

Respondent burden

3–5 minutes to complete (7).

Administrative burden

Training consists of self-study of the scoring documentation (7).

Translations/adaptations

English only.

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Topic-guided interviews with podiatric patients (7).

Acceptability

Not reported.

Reliability

The survey developers noted a combined Cronbach's alpha of 0.90 for the BFS, and the Cronbach's alpha for the individual subscales was not reported. Test– retest values from 36 patients over a 2-week wait-list period were –0.83; test–retest reliability of the individual subscales is unknown (7).

Validity

Content validity was evaluated by comparing the BFS with a clinical evaluation using the United Bristol Healthcare National Health Service Trust standard content validity with the Chiropody Assessment Criteria Score in a group of 54 podiatric patients (41 women and 13 men). There was a negligible, nonsignificant correlation between these scores with an r = 0.14, which suggests that these measures reflect different outcomes (5).

Ability to detect change

Barnett et al showed a BFS pre-post change of 1.2 ± 7.1 for the 54 patients after 2 weeks of routine care. In 49 patients (25 women and 24 men), there was an 18.7 ± 12.3 point pre-post change in the 6 weeks following nail surgery in their BFS (P = 0.01) (7). However, there are no independent studies determining the minimum detectable or minimum clinically important difference.

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

The BFS was developed based on patients’ perspectives of foot health and ailments, which provides it better content validity for assessing complaints.

Caveats and cautions

Psychometric evaluation for the BFS is limited, and there is no independent assessment of its psychometric properties. The 3 subdomains (i.e., foot concern and pain, footwear and general foot health, and mobility) do not show construct validity against other foot questionnaires or against a clinical assessment.

Clinical usability

The BFS was developed with focus groups, but without an independent study of its psycho-metric properties and without known values of the minimum detectable or minimum clinically important difference. The clinical utility of the BFS may be limited.

Research usability

Campbell (10) suggests that because the BFS was developed in a clinical setting, it is not as useful for monitoring the change in foot health in populations with a low risk of foot ailments.

REVISED FOOT FUNCTION INDEX (FFI-R)

Description

Purpose

To assess foot-related health and quality of life.

Content

Questions to evaluate overall foot function, foot health, and quality of life. The FFI-R has 4 subscales: pain and stiffness (19 questions), social and emotional outcomes (19 questions), disability (20 questions), and activity limitation (10 questions). The FFI has 3 subscales: pain (9 questions), disability (9 questions), and activity limitation (5 questions).

Number of items

Long-form FFI-R consists of 68 questions. Shorter form has 34 questions that only assess foot function, and it is not intended for analysis of subscales (11). The original FFI consists of 23 items on 3 subscales (12).

Response options/scale

FFI-R respondents answer on a Likert scale of 1–5. Some items also contain a sixth possible response indicating that it is not applicable to the respondent (11). FFI is scored on a visual analog scale between verbal anchors representing extremes (12).

Recall period for items

1 week.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (11), but it has also been used to assess orthotics outcomes (13).

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available in original publication (11).

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

If the 68-question FFI-R is administered, an index is calculated by summing responses and dividing by the maximum possible score on each subscale to obtain separate percentage scores for each. The 34-question FFI-R is used to obtain an overall score of foot function (11). On the FFI, visual scales are divided into 10 equal segments and the respondents’ mark classified as a number between 0 and 9. Scores are then summed on subscales, and evaluated as a percentage of the highest possible score (12).

Score interpretation

Range of 0–100% on each sub-scale, plus an overall percentage score. Higher scores indicate worsening foot health and poorer foot-related quality of life on both the FFI-R and FFI (11,12).

Respondent burden

Less than 30 minutes to complete (11).

Administrative burden

Self-study of the scoring documentation (11).

Translations/adaptations

FFI-R has 2 versions (long form and short form); previous version is FFI (12).

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Adapted from information obtained from previous survey, patient focus groups, and foot specialists (11).

Acceptability

The questionnaire is written for an eighth-grade reading level.

Reliability

The survey developers noted the FFI-R test– retest person reliability was 0.96 and the item reliability was 0.93. The developers also reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.93, 0.86, 0.93, and 0.88 for the pain, psychosocial, disability, and functional limitation subscales, respectively, indicating high internal reliability (11). The FFI survey developers reported the FFI as having a high test– retest reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.87 for the full questionnaire. Subscale ICCs were 0.69, 0.81, and 0.84 for the pain, disability, and activity limitation subscales, respectively. Budiman-Mak et al reported the FFI Cronbach's alpha as 0.96 for the full questionnaire, with subscale alpha of 0.73, 0.93, and 0.95 for the activity limitation, disability, and pain subscales, respectively, indicating high internal reliability (12).

Validity

FFI-R results were compared to a 50-foot walking time (11,12). Significant correlation was observed between walk times and the FFI-R score (r = 0.31, P = 0.018). The construct validity was also supported by the correspondence of items considered to indicate low severity of problems being associated with lower scores (indicating better foot health and function) (11). Factor analysis of the FFI showed overall construct validity, with all but 2 items weighing into a single factor. Analysis with varimax rotation also showed subscale validity, with all pain and disability items separating into 2 factors, and activity limitation items dividing between 2 additional factors. Content validity was gauged by correlation with 50-foot walk times and counts of painful joints. The FFI had a moderate overall correlation of 0.48 and 0.53 when compared to walk times and painful joint counts, respectively (12).

Ability to detect change

Minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference have not been reported for the FFI-R. The pain and activity limitation subscales of the FFI have been correlated to changes in the number of painful joints over 6 months (r = 0.47, P = 0.002 and r = 0.34, P = 0.03, respectively). There was no significant relationship observed between the disability subscale and the number of painful joints (r = 0.11, P = 0.51) (12). In an independent study examining treatment of plantar fasciitis in 175 patients, Landorf and Rad-ford (14) found the minimally important difference on the FFI was –0.5 points for activity limitation, –12.3 points for pain, and –6.7 points for disability, with a total FFI change of –6.5. Negative scores denoted improved foot-related health.

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

The FFI-R provides both a short and long form, which provides the researcher an option of the level of detail necessary.

Caveats and cautions

FFI-R is a questionnaire based on the original FFI, seeking to address criticisms relating to the original index's basis, administrative issues, validity, and psychometric properties (11,15). Though based on the FFI, the FFI-R is a notably different survey in length, construction, and content. While the FFI-R is the newer survey, many researchers continue to use the older, more established FFI. However, because the FFI and FFI-R are different, it is difficult to compare results between these surveys.

Clinical usability

The FFI-R was developed through patient and focus groups, but its validity, reliability, and sensitivity to change have not been independently evaluated. The FFI-R, similar to several other foot-related patient-reported outcome measures, lacks an independent review of the psychometric properties and lacks information regarding the minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference, which limits its clinical usability.

Research usability

The FFI-R was developed from the original FFI and a literature review, as well as focus groups with foot specialists, interviews with foot specialists and podiatric patients, and results from patient surveys (11). As a result, the FFI-R is noted to be a well-developed measure of foot health–related quality of life (16); however, because it is also a newer survey, there are fewer independent studies evaluating its utility.

FOOT HEALTH STATUS QUESTIONNAIRE (FHSQ)

Description

Purpose

Content

Questions regarding foot health and its impact on quality of life. There are 4 subscales: foot pain (4 questions), foot function (4 questions), footwear (3 questions), and general foot health (2 questions).

Number of items

13 questions.

Response options/scale

For the subscales of pain, function, and general foot health, a 5-point Likert scale of no problems, pain, or limitations to severe problems, pain, or limitations. Responses to footwear questions are on a 5-point bipolar Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree for statements regarding shoe fit, discomfort wearing shoes, and shoewear available.

Recall period for items

1 week.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

Used to assess the effects of footwear (19) and orthotic interventions (20,21), and foot health in the community (22), as well as in various podiatric clinical populations (23–25).

Practical Application

How to obtain

Survey and scoring program are available through the FHSQ web site at URL: http://fhsq.home stead.com/index.html. Its current price is AUS $150.

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

Dedicated FHSQ program scores questionnaires. When fewer than 50% of the responses for any one scale are missing, the missing responses are assigned with the average value of the completed questions for that scale (17).

Score interpretation

Subscale scores are reported as 0 (poorest state of foot health) to 100 (optimal foot health). Higher scores reflect better foot health and quality of life (17,18).

Respondent burden

Less than 10 minutes to complete.

Administrative burden

Not reported.

Translations/adaptations

Original in English (17,18), with translated versions in Brazilian Portuguese (26) and Spanish (Valencian culture) (27).

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Content was developed with input from focus groups of podiatric surgeons.

Acceptability

Not reported.

Reliability

The survey developers reported the FHSQ Cronbach's alpha for subscales was 0.85 (footwear), 0.86 (foot function), 0.88 (general foot health), and 0.88 (foot pain) in a sample of 111 podiatric patients (18) and 0.89– 0.95 (individual alpha for each subscale not provided) (17). These alphas were between the accepted 0.7–0.9 range (28). The survey developers noted the intraclass correlations were 0.74 (footwear), 0.78 (general foot health), 0.86 (foot pain), and 0.92 (foot function) for the test–retest reliability of 72 patients who completed the survey before and after a week of routine care, noting a high reliability (18).

Validity

The survey developers assessed validity with 111 podiatric patients. The root mean standard error of approximation was 0.08, which suggests a moderate fit of the FHSQ to measure foot health related to quality of life (29). The goodness-of-fit index, an absolute index of fit, was 0.90, while the comparative fit index (CFI), a relative measure of fit, was 0.96 (17). The CFI depends on the average size of the correlations in the data, so a high value suggests a high correlation between variables. The CFI was above the recommended 0.95 cutoff (30), suggesting high validity.

Ability to detect change

In an independent study examining treatment of plantar fasciitis in 175 patients, Landorf and Radford (14) found the minimally important difference for pain was 14 points (i.e., pain scores increased by 14 points), for function was 7 points, and general foot health was 9 points to denote improved foot-related health. An independent study also evaluated the clinically relevant responsiveness of the FHSQ foot function sub-scale in 784 ethnically diverse older adults (31). In this study, the FHSQ foot function subscale scores differed between 3 groups of participants. Participants in one group with minor foot pathology (e.g., hyperkeratosis and nail pathology) had a mean FHSQ foot function subscale score of 88.8. Participants who had a morphologic disorder (e.g., hammertoes) had a mean FHSQ foot function sub-scale score of 77.9. Participants in a third group with acute disease (e.g., plantar fasciitis) had an average FHSQ foot function subscale score of 53.9. The decrements of FHSQ scores associated with an increasing number of foot disorders in this study ranged between 10 and 20 points, similar to the differences reported earlier. These results suggest that the changes in foot function FHSQ subscores are clinically relevant to poorer foot function as a result of an increasing number of foot disorders (18,31).

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

The 4 subscales are representative of health and health impact on quality of life and disability (32,33). Moreover, the FHSQ has more psychometric data available compared to others (16) and is used within a number of research settings, despite its cost.

Caveats and cautions

Trevethan argues that better psychometric analyses would allow for some questions to be removed and could reduce the participant burden (15). Further, this questionnaire does not evaluate the impact of foot health with regard to its impact on the participant's psychological state, social activities, or self-esteem, all of which may influence quality of life and patient satisfaction (3).

Clinical usability

With known values of the minimal important difference, as well as many of the psychometric properties, the FHSQ is frequently used in clinical settings.

Research usability

With high validity and an independent study assessing minimal important differences, this foot-related patient-reported outcome measure has well-detailed psychometric properties and is one of the most common foot surveys.

MANCHESTER FOOT PAIN AND DISABILITY INDEX (MFPDI)

Description

Purpose

To measure disabling foot pain in the general population (34).

Content

Questions of foot health as they relate to foot pain, functional limitations, and self/body image. The original survey has 3 subscales: functional limitation (10 questions), pain intensity (5 questions), and perception of one's appearance as a result of foot problems (2 questions) (34). Menz et al performed an independent factor analysis using a sample of 301 older adults in Australia, which showed 4 subscales: functional limitation (7 questions), activity restrictions (2 questions), pain (6 questions), and concern over foot appearance (2 questions) (35). The Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire (MOXFQ) showed 3 subscales from a factor analysis: walking/standing domain (7 items), pain (5 questions), and social interactions (4 items) (36). The factor analysis by Cook et al noted 2 subscales: foot and ankle function (9 questions) and pain and appearance (7 questions) (37).

Number of items

17 questions in the original (34) or 16 questions after a separate item response theory analysis (37). The MOXFQ also has 16 questions (36).

Response options/scale

Responses have 3 levels of severity (never, sometimes, always), which are transformed into numerical scores (and summed within each subscale).

Recall period for items

1 month.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

Used as a general population survey of adults and older adults (35) to evaluate disabling foot pain (34,35,38) or hallux valgus surgery (36).

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available in the original publication (34).

Method of administration

Self-administered or inter view (34).

Scoring

Items are summed per scoring guide of version used (34–37). Original publication assigns the severity level values of 1–3, corresponding to increasing severity (34). Subsequent publications have also evaluated an overall score expressed as the sum of each subscale score or as a percentage of the total possible outcome (35).

Score interpretation

The range varies depending on the scoring technique used, and original survey used a 0–2 scale, yielding a score range of 0–34 (34). Cook et al and Waxman et al used a 1–3 scoring for range of 17–51 (37,39). Higher scores correspond to more severe foot pain and disability (34).

Respondent burden

Not reported.

Administrative burden

Translations/adaptations

Original is in English; Greek (40), Italian (41), and Brazilian Portuguese (42) versions have also been validated. The MOXFQ was developed from the MFPDI to assess hallux valgus corrective surgery (36). Cook et al performed a graded response item response theory analysis to reduce the MFPDI by 1 less question (37).

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Open-ended interviews with 32 patients who visited a foot clinic (34).

Acceptability

Not reported.

Reliability

Garrow et al (34) reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.99 (34), whereas an independent study noted it as 0.89 (35), indicating high reliability. Both research groups stated the questionnaire has high consistency (no statistics provided) with self-report of injury during separate patient interviews in younger and older populations (34,35). In the MOXFQ survey, Dawson et al reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.73, 0.86, and 0.92 for the social interaction, pain, and walking/standing subscales, respectively, when evaluating 100 hallux valgus surgery patients (36). These Cronbach's alpha coefficients were between the accepted 0.7–0.9 range (28).

Validity

Content of the survey was generated with patient interviews, and the construct validated through the comparison of responses from groups with known systematic differences in foot conditions. The criteria of the MFPDI were also compared to similar items in the ambulation subscale of the Function Limitation Profile Questionnaire. This comparison showed that items with similar wording had a Cohen's kappa of 0.48 and 0.50, and a much lower kappa (0.17) for differently worded items (34). Cohen's kappa is a measure of agreement with higher values indicating better agreement, with moderate agreement ranging from 0.4–0.6 and slight agreement <0.2 (43). The functional limitation and activity restriction subscales have been shown to be significantly correlated with the Short Form 36 (SF-36) mental (r = 0.20, P = 0.04) and general (r = 0.21, P = 0.03) health subscales (35). The Dawson et al study of 100 hallux valgus surgery patients also assessed the MOXFQ validity (36). MOXFQ walking/ standing subscale was strongly associated (P < 0.001) with the SF-36 physical functioning (Spearman's correlation r = 0.68), role physical (r = 0.58), and pain (r = 0.54) domains, and with the SF-36 physical component summary score (r = 0.63). The MOXFQ was strongly associated (P < 0.001) with the SF-36 pain subscale (r = 0.53).

Ability to detect change

The original MFPDI does not have reported sensitivity, responsiveness, or minimal important difference data. The MOXFQ assessment of corrective hallux valgus treatment does provide data regarding the subscale minimally important differences. Dawson et al noted the minimum clinically important differences were 12.8 points (effect size 0.4), 4.6 points (effect size 0.2), and 20.3 points (effect size 0.8) for the walking/ standing, pain, and social interaction subscales, respectively. In evaluating pain transition, receiver operating characteristic curves provided cut points for the MOXFQ. The suggested cut points were 14 points for the walking/ standing scale and 25 points for both the pain and social interaction scales to indicate a minimally important amount of change.

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

MFPDI measures foot pain and functional limitations from multiple perspectives and with multiple questions, which provides an appropriate means for reducing measurement error (44).

Caveats and cautions

The MFPDI provides only 2 questions for addressing footwear, and there are no questions regarding self/body image. Because footwear can affect self/body image (45), this questionnaire may not capture the effects of footwear or footwear interventions from the patient's perspective.

Clinical usability

There are several different assessment models and adaptations of the MFPDI developed. However, within these surveys and scoring methods, only the MOXFQ has minimally important differences noted in populations with hallux valgus. The other adaptations from the MFPDI should be further independently evaluated for their minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference to improve their clinical utility.

Research usability

Menz et al noted there were 4 sub-scales instead of 3 for their population of older adults (35). In an independent analysis of the 3 assessment models (3 domains in the Garrow et al original study [34], 4 subscales in the Menz et al study of older adults [35], and 2 domains of the Cook et al study [37]), the Garrow et al study performed better (lower root mean square error of approximation [0.065], higher comparative fit index [0.949], and higher normed fit index [0.943]) than the other 2 studies in a survey of adults over age 50 (46). Therefore, the correct scoring model should be evaluated relevant to the population studied.

PODIATRIC HEALTH QUESTIONNAIRE (PHQ)

Description

Purpose

To measure foot-related health in podiatric patient populations (47).

Content

Questions related to walking, foot health, foot pain, worry about feet, and impact of the foot on quality of life. Includes 7 subscales: walking, foot hygiene, nail care, foot pain, worry about feet, and impact on quality of life, with one question each and separate visual analog scale (VAS) for current foot status.

Number of items

6 questions and 1 VAS, for a total of 7 items.

Response options/scale

Each dimension has 1 question related to it with 3 severity levels (no problems, some problems, and severe problems). 20-cm VAS delineated from 0–100.

Recall period for items

1 day.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

PHQ has been used in podiatric patient populations with various foot ailments and systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes (47,48).

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available in the original article (47).

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

6 dimensions are summed per scoring guide to generate a single score ranging from 6–18.

Score interpretation

Higher scores indicate more severe problems, and a higher VAS score indicates better foot health. Scoring is categorical, based on the level of severity (level 1 = no problems to level 3 = severe problems). The VAS is delineated from 0 (worst possible foot health) to 100 (best possible foot health) for the response item “How are your feet today?” (47).

Respondent burden

Not reported.

Administrative burden

Training of the podiatric staff for the PHQ and clinical podiatric assessment is 2 hours (47).

Translations/adaptations

English only.

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Consultation of podiatric managers and podiatric clinicians (47).

Acceptability

Not reported.

Reliability

Unknown.

Validity

The survey developers validated the PHQ against the generic health status assessment of the EuroQol 5-Domain instrument (EQ-5D) and an objective clinical assessment in which a podiatrist objectively scored the patient's foot health from 1 (no foot problems) to 5 (severe foot problems) (47). Comparing the PHQ to the clinical podiatric assessment, the Goodman-Kruskal lambda for the 2,038 patients for each dimension was: walking 0.15, hygiene –0.09, nail care –0.24, foot pain 0.41, worry/ concern for feet 0.30, and impact on quality of life 0.31. The PHQ was noted to be more robust in detecting foot-related health than the EQ-5D when it was compared to the clinical podiatric assessment (the subscale Goodman-Kruskal lambda ranged from 0.13–0.02) (47). Goodman-Kruskal lambda is a measure of the proportional ability of predicting the outcome for 1 categorical variable based on a second categorical variable. For construct validity, the PHQ subscales were correlated to the EQ-5D components ranging from 0.58–0.14 using Kendal correlation coefficients, and the PHQvas and EQ-5Dvas had a 0.40 Kendal correlation coefficient (47). These values suggest a low to moderate correlation, suggesting that the PHQ and EQ-5D detect different aspects of health.

Ability to detect change

In an independent study, Farndon et al used the PHQ to determine changes in foot status over a 2-week period after a podiatric intervention of 1,047 patients in 8 podiatric clinics (48). In 2 weeks, they noted a significant (P < 0.001) change in the PHQ dimension scores and the PHQvas for their patients. The PHQ of the 6 dimensions decreased by 0.5 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.4–0.7). The PHQvas decreased by 0.7 (95% CI 0.6–0.9) using the PHQvas on a 0–10 scale (no pain to worse pain). While they initially used a clinical assessment to validate their PQH and PHQvas scores, in the followup PQH assessment, there was no followup clinical assessment to assess the validity of the change in scores. Therefore, the minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference are both unknown.

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

In terms of the number of survey questions, the PHQ is one of the shortest foot-related patient-reported outcome measures, which can limit the participant burden.

Caveats and cautions

The PHQ is a 1 question per domain measurement of foot health. This allows for patients and survey participants to quickly take the questionnaire; however, this may also increase measurement error because there is no means of ensuring the question was understood or was a representative answer of the impact of foot health on the patient's quality of life (44).

Clinical usability

Without known minimum detectable difference and minimum clinically important difference, the clinical utility of this survey is limited. Further, there are no questions regarding foot function, orthotics, and shoewear, all of which are important features of podiatric treatment and evaluation.

Research usability

Perhaps due to the sparseness of this survey with regard to the number and type of questions, this survey is not commonly used in research settings.

ROWAN FOOT PAIN ASSESSMENT (ROFPAQ)

Description

Purpose

To evaluate chronic foot pain (49).

Content

Addresses the 3 pain dimensions: sensory, affective (motivational), and cognitive (49,50). 3 subscales: sensory (16 questions), affective (10 questions), and cognitive (10 questions), with 3 additional questions used as indicators of understanding.

Number of items

39 questions.

Response options/scale

Each question has a Likert scale from 1 (no foot pain or foot pain does not affect patient) to 5 (extreme foot pain or foot pain significantly affects patient). The subscale questions (i.e., sensory, affective, and cognitive) are distributed throughout the questionnaire in lieu of being grouped by domain, and they should be scored within each subscale (49). The 3 comprehension questions should be assessed to see if they are similar.

Recall period for items

Unspecified.

Endorsements

None.

Examples of use

Podiatric patients with chronic foot pain.

Practical Application

How to obtain

Available in the appendix of the original article (49).

Method of administration

Self-administered.

Scoring

Scores within each subdomain are summed, with the sensory domain score ranging from 16–80, and the affective and cognitive domains ranging from 10–50.

Score interpretation

Higher scores suggest that foot pain has a greater effect on the patient's pain domains and is less ideal for the patient. The 3 comprehension questions should have a 90% agreement; if comprehension scores are less than 90%, the survey administrator should have the patient retake the survey or verbally clarify the statements since it may indicate either patient carelessness or question misunderstanding.

Respondent burden

Mean completion time is 9 minutes (range 2–20 minutes) (49).

Administrative burden

Self-study of the scoring documentation (49).

Translations/adaptations

English only.

Psychometric Information

Method of development

Data from 6 focus groups and 2 semistructured interviews used to guide development (49).

Acceptability

Reported Flesch reading ease score of 74.8, which is slightly better than average readability (49).

Reliability

Thirty-nine participants (26 women and 13 men) with foot pain for more than 1 year took the ROFPAQ survey to assess reliability and validity measures. The survey developer noted the internal consistency scores were 0.90 (sensory), 0.81 (affective), and 0.87 (cognitive), between the accepted values of 0.7 and 0.9 (49). The Spear-man's test–retest reliability coefficients were 0.88 (sensory), 0.93 (affective), and 0.82 (cognitive) when participants took the ROFPAQ twice, 24 hours apart, indicating high reliability.

Validity

Validity, the ability of the survey to detect chronic foot pain over other types of pain, was supported in that the survey distinguishes the effects of chronic foot pain over headache pain. To measure convergent validity, the ROFPAQ was compared to the Foot Function Index (FFI) pain subscale (12); the Spearman's correlation coefficients between these scales were 0.88 (sensory), 0.69 (affective), and 0.70 (cognitive). As the subdomains of the ROFPAQ were correlated to the FFI pain measure, the author states that this suggests that the ROFPAQ measures more than the sensory domain of pain (49). No independent studies have examined the validity of the ROFPAQ.

Ability to detect change

Unknown.

Critical Appraisal of Overall Value to the Rheumatology Community

Strengths

The ROFPAQ was designed and validated to assess the 3 domains of foot pain, and it does evaluate pain from multiple perspectives (sensory, affective [motivational], and cognitive).

Caveats and cautions

Since this survey was only designed to assess foot pain, it does not measure the commonly associated features of foot pain (e.g., foot function, foot health, and shoewear).

Clinical usability

The ROFPAQ was designed to measure the 3 dimensions of chronic foot pain; as a result, this assessment does not model foot health on quality of life as well as other questionnaires. Therefore, it is best suited for assessing treatment modalities in podiatric clinical populations as opposed to community-based studies of foot health.

Research usability

The ROFPAQ does not have an independent study of its psychometric properties, and the survey is not commonly used, which limits the ability to evaluate results across research and clinical populations. Further, because the survey only measures foot pain without regard to other commonly associated features of foot pain (e.g., foot function, foot health, or shoewear), it suggests that including a separate survey or set of questions regarding these aspects may be necessary to fully evaluate the role of foot pain on the participant's life.

DISCUSSION

This review has described several of the instruments used to measure foot-related patient-reported outcome measures in adults. Table 1 lists the content comparisons of these foot health questionnaires. Currently, the area of foot health and foot function is garnering greater attention in the rheumatology community. Thus, there is a great need for valid and reliable instruments and surveys to measure foot health. However, many of the foot-related patient-reported outcome measures have limited evidence regarding their validity and responsiveness to change, limiting their use in clinical intervention and population studies. It is important to note that this review is limited to instruments primarily used in adults, and further work is needed to include pediatric measures. Future work should evaluate the psychometric properties and clinical utility of these foot-related patient-reported outcome measures.

Table 1.

Content of patient-reported foot health questionnaires*

| Foot pain |

Foot health |

Foot function |

Functional limitation/disability |

Self-perception/ body image |

Psychological | Social | Orthotics/ shoewear |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAOS-FAM | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| BFS | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FFI-R | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – |

| FHSQ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| MFPDI | Yes | – | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | – |

| PHQ | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes | – | – |

| ROFPAQ | Yes | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – |

AAOS-FAM = American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Lower Limb Outcomes Assessment: Foot and Ankle Module; BFS = Bristol Foot Score; FFI-R = Revised Foot Function Index; FHSQ = Foot Health Status Questionnaire; MFPDI = Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index; PHQ = Podiatric Health Questionnaire; ROFPAQ = Rowan Foot Pain Assessment.

Summary Table for Self-Administered Patient/Participant-Reported Foot Health Questionnaires*

| Scale | Purpose/content | Number of items | Subscales (no. questions) | Reliability evidence | Validity evidence | Ability to detect change | MDD | MCID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAOS-FAM | Evaluate patient perception of foot health and measure surgical outcomes | 25 questions in 5 subscales | Pain (9 questions); foot function (6 questions); stiffness and swelling (2 questions); giving way (3 questions); shoe comfort (5 questions) | Good | Good | Good | Unknown | Unknown |

| BFS | Assess patient perception of impact of foot problems on everyday life | 15 questions in 3 subscales | Foot concern and pain (7 questions); footwear and general foot health (4 questions); mobility (3 questions) | Adequate | Good | Good | Unknown | Unknown |

| FFI-R | Assess foot-related health and quality of life | 34 or 68 questions, with 68 questions (long form) having 4 subscales (items in this table are for long form) | Pain and stiffness (19 questions); social and emotional outcomes (19 questions); disability (20 questions); activity limitation (10 questions) | Excellent | Good | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| FHSQ | Measure foot health related to quality of life | 13 questions in 4 subscales | Foot pain (4 questions); foot function (4 questions); footwear (3 questions); general foot health (2 questions) | Good | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| MFPDI | Measure disabling foot pain in general population | 17 questions in 3 subscales | Functional limitation (10 questions); pain intensity (5 questions); perception or foot appearance (2 questions) | Good | Good | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| PHQ | Measure foot-related health in podiatric patient populations | 7 items (1 question in 6 subscales and visual analog scale) | 1 question each for: walking, foot hygiene, nail care, foot pain, worry about feet, quality of life. Visual analog scale for current foot status | Unknown | Good | Good | Unknown | Unknown |

| ROFPAQ | Evaluate chronic foot pain | 39 questions in 3 subscales and comprehension questions | Sensory (16 questions); affective (10 questions); cognitive (10 questions) | Excellent | Good | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

MDD = minimum detectable difference; MCID = minimum clinically important difference; AAOS-FAM = American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Lower Limb Outcomes Assessment: Foot and Ankle Module; BFS = Bristol Foot Score; FFI-R = Revised Foot Function Index; FHSQ = Foot Health Status Questionnaire; MFPDI = Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index; PHQ = Podiatric Health Questionnaire; ROFPAQ = Rowan Foot Pain Assessment.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Lower Limb Outcomes Assessment: Foot and Ankle Module (AAOS-FAM), Bristol Foot Score (BFS), Revised Foot Function Index (FFI-R), Foot Health Status Questionnaire (FHSQ), Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index (MFPDI), Podiatric Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and Rowan Foot Pain Assessment (ROFPAQ)

REFERENCES

- 1.Johanson NA, Liang MH, Daltroy L, Rudicel S, Richmond J. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons lower limb outcomes assessment instruments: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:902–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunsaker FG, Cioffi DA, Amadio PC, Wright JG, Caughlin B. The American academy of orthopaedic surgeons outcomes instruments: normative values from the general population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:208–15. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1507–15. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller RB. AAOS/council of musculoskeletal specialty societies’ outcomes instruments. Curr Opin Orthop. 1996;7:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallander H, Larsson S, Bjonness T, Hansson G. Patient-reported outcome at 62 to 67 years of age in 83 patients treated for congenital clubfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1316–21. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B10.22796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinker MR, O'Connor DP. Outcomes of tibial nonunion in older adults following treatment using the Ilizarov method. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:634–42. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318156c2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett S, Campbell R, Harvey I. The Bristol Foot Score: developing a patient-based foot-health measure. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95:264–72. doi: 10.7547/0950264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malay DS, Yi S, Borowsky P, Downey MS, Mlodzienski AJ. Efficacy of debridement alone versus debridement combined with topical antifungal nail lacquer for the treatment of pedal onychomycosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:294–308. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugathan HK, Sherlock DA. A modified Jones procedure for managing clawing of lesser toes in pes cavus: long-term follow-up in 8 patients. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:637–41. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell JA. Characteristics of the foot health of “low risk” older people: a principal components analysis of foot health measures. Foot. 2006;16:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budiman-Mak E, Conrad K, Stuck R, Matters M. Theoretical model and Rasch analysis to develop a revised Foot Function Index. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:519–27. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budiman-Mak E, Conrad KJ, Roach KE. The Foot Function Index: a measure of foot pain and disability. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:561–70. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao S, Baumhauer JF, Tome J, Nawoczenski DA. Orthoses alter in vivo segmental foot kinematics during walking in patients with midfoot arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landorf KB, Radford JA. Minimal important difference: values for the Foot Health Status Questionnaire, Foot Function Index and Visual Analogue Scale. Foot. 2008;18:15–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevethan R. Evaluation of two self-referent foot health instruments. Foot (Edinb) 2010;20:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walmsley S, Williams A, Ravey M, Graham A. The rheumatoid foot: a systematic literature review of patient-reported outcome measures. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett PJ, Patterson C. The foot health status questionnaire (FHSQ): a new instrument for measuring outcomes of foot care. Australasian J Podiatr Med. 1998;32:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett PJ, Patterson C, Wearing S, Baglioni T. Development and validation of a questionnaire designed to measure foot-health status. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1998;88:419–28. doi: 10.7547/87507315-88-9-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams AE, Rome K, Nester CJ. A clinical trial of specialist footwear for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:302–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns J, Crosbie J, Ouvrier R, Hunt A. Effective orthotic therapy for the painful cavus foot: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:205–11. doi: 10.7547/0960205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rome K, Gray J, Stewart F, Hannant SC, Callaghan D, Hubble J. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of foot orthoses in the treatment of plantar heel pain: a feasibility study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004;94:229–38. doi: 10.7547/0940229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn JE, Link CL, Felson DT, Crincoli MG, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:491–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beeson P, Phillips C, Corr S, Ribbans WJ. Hallux rigidus: a cross-sectional study to evaluate clinical parameters. Foot (Edinb) 2009;19:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maher AJ, Metcalfe SA. First MTP joint arthrodesis for the treatment of hallux rigidus: results of 29 consecutive cases using the foot health status questionnaire validated measurement tool. Foot (Edinb) 2008;18:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radford JA, Landorf KB, Buchbinder R, Cook C. Effectiveness of low-Dye taping for the short-term treatment of plantar heel pain: a randomised trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira AF, Laurindo IM, Rodrigues PT, Ferraz MB, Kowalski SC, Tanaka C. Brazilian version of the foot health status questionnaire (FHSQ-BR): cross-cultural adaptation and evaluation of measurement properties. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:595–600. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000500005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirera-Vercher MJ, Saez-Zamora P, Sanz-Amaro MD. Translation, trans-cultural adaptation to Spanish, to Valencian language of the Foot Health Status Questionnaire. Revista Espanola de Cirugia Ortopedica y Traumatologia (English Edition) 2010;54:211–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.British Psychological Society Steering Committee on Test Standards. Psychological testing: a user's guide. The British Psychological Association; Leicester (UK): 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage Publishing; Beverly Hills (CA): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badlissi F, Dunn JE, Link CL, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB, Felson DT. Foot musculoskeletal disorders, pain, and foot-related functional limitation in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1029–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tully MP, Cantrill JA. Subjective outcome measurement: a primer. Pharm World Sci. 1999;21:101–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1008694522700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization . Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health. ICF; URL: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/site/beginners/bg.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrow AP, Papageorgiou AC, Silman AJ, Thomas E, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess disabling foot pain. Pain. 2000;85:107–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menz HB, Tiedemann A, Kwan MM, Plumb K, Lord SR. Foot pain in community-dwelling older people: an evaluation of the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:863–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawson J, Coffey J, Doll H, Lavis G, Cooke P, Herron M, et al. A patient-based questionnaire to assess outcomes of foot surgery: validation in the context of surgery for hallux valgus. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1211–22. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook CE, Cleland J, Pietrobon R, Garrow AP, Macfarlane GJ. Calibration of an item pool for assessing the disability associated with foot pain: an application of item response theory to the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Physiotherapy. 2007;93:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrow AP, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. The Cheshire Foot Pain and Disability Survey: a population survey assessing prevalence and associations. Pain. 2004;110:378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waxman R, Woodburn H, Powell M, Woodburn J, Blackburn S, Helli-well P. FOOTSTEP: a randomized controlled trial investigating the clinical and cost effectiveness of a patient self-management program for basic foot care in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1092–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaoulla P, Frescos N, Menz HB. Development and validation of a Greek language version of the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marinozzi A, Martinelli N, Panasci M, Cancilleri F, Franceschetti E, Vincenzi B, et al. Italian translation of the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire, with re-assessment of reliability and validity. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:923–7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrari SC, Cristina dos Santos F, Guarnieri AP, Salvador N, Abou Hala Correa AZ, Abou Hala AZ, et al. Indice Manchester de incapacidade associada ao pe doloroso no idoso: traducao, adaptacao cultural e validacao para a lingua portuguesa. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia. 2008;48:335–41. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King G, Murray CJ, Salomon JA, Tandon A. Enhancing the validity and cross-cultural comparability of measurement in survey research. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2004;98:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams A, Nester C, Ravey M. Rheumatoid arthritis patients’ experiences of wearing therapeutic footwear: a qualitative investigation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roddy E, Muller S, Thomas E. Defining disabling foot pain in older adults: further examination of the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:992–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macran S, Kind P, Collingwood J, Hull R, McDonald I, Parkinson L. Evaluating podiatry services: testing a treatment specific measure of health status. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:177–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1022257005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farndon L, Barnes A, Littlewood K, Harle J, Beecroft C, Burnside J. Clinical audit of core podiatry treatment in the NHS. J Foot Ankle Res. 2009;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowan K. The development and validation of a multi-dimensional measure of chronic foot pain: the Rowan Foot Pain Assessment Questionnaire (ROFPAQ). Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:795–809. doi: 10.1177/107110070102201005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melzack R, Casey KL. Sensory, motivational and central control determinants of chronic pain: a new conceptual model. The Skin Senses. 1968:423–43. [Google Scholar]