Abstract

An environmental isolate of Serratia fonticola resistant to carbapenems contains a gene encoding a class A β-lactamase with carbapenemase activity. The enzyme was designated SFC-1. The blaSFC-I gene is contained in the chromosome of S. fonticola UTAD54 and is absent from other S. fonticola strains.

The prokaryotic species Serratia fonticola, a species of the family Enterobacteriaceae, includes organisms that occur naturally in environmental waters (3); occasionally, some strains cause infections in humans (15). A recent study on the natural antimicrobial susceptibilities of strains of Serratia species (23) showed that S. fonticola expresses both a chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase and a species-specific AmpC β-lactamase. The class A enzyme corresponds to the previously characterized β-lactamase SFO-1 (13), and the homologous sequence FON-A (GenBank accession no. AJ251239) is common to S. fonticola (19).

In a previous report (18), an environmental isolate designated S. fonticola UTAD54 was shown to be resistant to carbapenems. This phenotype could be attributed to a gene encoding a class B metallo-enzyme (Sfh-I) that was isolated from a genomic library (18). An additional screening of the library was done on Luria-Bertani plates supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) to select for inserts and the vector, respectively. Some of the clones obtained were negative when screened by PCR using primers (18) for genes homologous to SFO-1. A recombinant plasmid containing a 1.8-kb insert was selected for study and designated pIH18.

Characterization of a new β-lactamase gene.

Plasmid DNA was prepared with a Qiaprep kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France), and both strands of the insert were sequenced on an ABI cycle sequencer A373 (Applied Biosystems/Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) using the ABI Prism dye terminator kit.

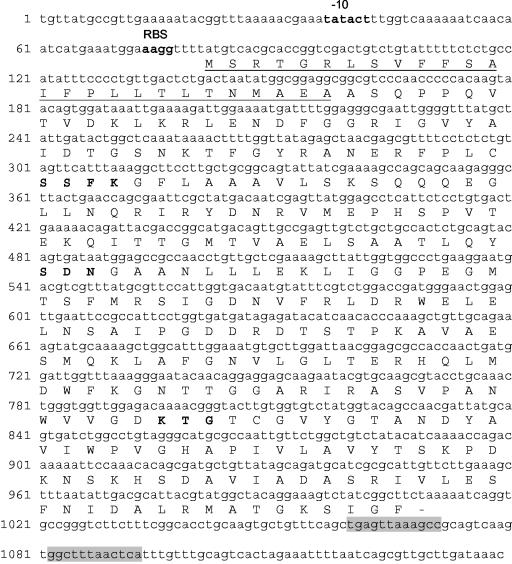

Analysis of sequence data revealed the presence of an open reading frame of 927 bp encoding a 33.6-kDa protein containing 309 amino acids (Fig. 1). Four nucleotides upstream of the ATG codon have the sequence AAGG, a putative ribosome-binding site (RBS). A typical −10 region (TATACT) was identified upstream from the RBS; no conserved −35 region could be assigned. Downstream, the open reading frame is a palindromic sequence (Fig. 1) which might form a hairpin loop in the mRNA, typical of a transcription terminator. The overall G+C content of blaSFC-1 (45.3%) is characteristic of genes of Enterobacteriaceae.

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the SFC-1 gene and its upstream and downstream regions. The putative −10 region and a potential RBS are in bold. The inverted repeat sequences that can act as a terminator of transcription are shaded. The putative signal peptide for protein secretion is underlined. Amino acids that correspond to conserved domains of class A β-lactamases are shown in bold.

A similarity search was performed with BLAST (1). SFC-1 had the highest similarity to the class A carbapenemases, in particular KPC-1 (62% identical) from Klebsiella pneumoniae (21), Sme-1 (58%), NMC-A (59%), and IMI-1 (59%) (12). Lower similarity scores were returned for the other class A β-lactamases. No putative LysR-type regulator gene was identified upstream of the blaSFC-I gene, whereas such regulators are transcribed upstream of the genes coding for NMC-A, Sme-1, and IMI-1 (7, 8).

The software SignalP (11) identified a bacterial signal peptide of 26 amino acids in the amino-terminal sequence (Fig. 1). Cleavage of this signal peptide would yield a mature protein of 30.7 kDa with a pI of 7.95.

Within the mature protein, a serine-serine-phenylalanine-lysine tetrad (S-S-F-K) was found, as was a lysine-threonine-glycine (KTG) motif. These motifs (SXXK and KTG) are characteristic of serine β-lactamases (16, 22). The nine invariant residues typical of class A enzymes (G45, S70, K73, P107, S130, D131, A134, E166, and G236) are conserved in the SFC-1 sequence. From the residues suggested to be important for class A carbapenemase activity (C69, S70, K73, H105, S130, R164, E166, N170, D179, R220, K234, S237, and C238), only S237 was not conserved in the SFC-1 sequence.

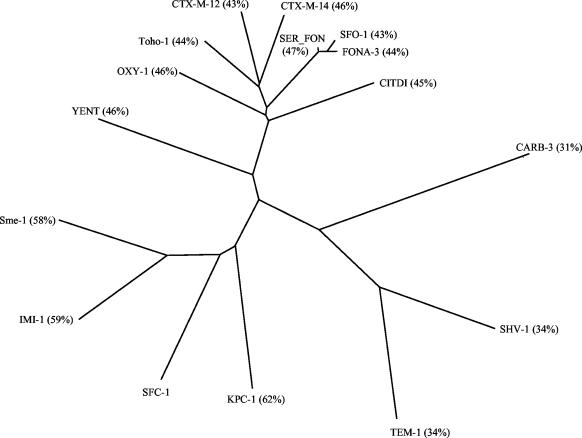

The deduced amino acid sequence of SFC-1 was aligned to the sequences of 15 class A β-lactamases, using CLUSTAL W at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory website (http://www.embl-heidelberg.de/). The enzymes and their GenBank accession numbers were the following: KPC-1 (24) from K. pneumoniae (AAG13410), IMI-1 (17) from Enterobacter cloacae (AAR93461), Sme-1 (9) from Serratia marcescens (CAA82281), OXY-1 (2) from Klebsiella oxytoca (P22391), CITDI (14) from Citrobacter diversus (S19006), YENT (20) from Yersinia enterocolitica (Q01166), CTX-M-12 (19) from K. pneumoniae (AAG34108), CTX-M-14 (19) from Escherichia coli (CAC95170), Toho-1 (6) from E. coli (BAA07082), SFO-1 (6) from E. cloacae (BAA76882), FONA-3 from S. fonticola (CAB61639), SER_FON (13) from S. fonticola (P80545), TEM-1 (24) from E. coli (AAR25033), SHV-1 (24) from E. coli (P14557), and CARB-3 (4) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P37322). The dendrogram shown in Fig. 2 was derived from the alignment: SFC-1 clusters to the class A carbapenemases and is more closely related to a subgroup that includes the enterobacterial enzymes of extended hydrolytic spectrum.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram obtained from the multiple sequence alignment of 15 class A β-lactamases. The percent identity between the amino acid sequence of each enzyme and that of SFC-1 is indicated in brackets.

Susceptibility to antibiotics.

The MICs were determined by the E-test method (Biodisk, Solna, Sweden), and susceptibility categories were allocated according to those described in reference 10. Table 1 shows the MICs for S. fonticola UTAD54, E. coli transformed with plasmid pIH18, and untransformed E. coli. The DNA insert encoding SFC-1 when replicating in E. coli confers resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin, piperacillin, cephalothin, and aztreonam and reduced susceptibility to meropenem and imipenem, and its activity is inhibited by the class A β-lactamase inhibitors. Such a resistance pattern is characteristic of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase.

TABLE 1.

MICs of antibiotics for S. fonticola UTAD54, E. coli XL2 Blue(pIH18), and E. coli XL2 Blue (reference strain)

| Antibiotica | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. fonticola UTAD54 | E. coli XL2 Blue(pIH18) | E. coli XL2 Blue | |

| Ampicillin | >256 | >256 | 2 |

| Amoxicillin | >256 | >256 | 4 |

| Amoxicillin-CLA | 12 | 32 | 3 |

| Piperacillin | 32 | 64 | 0.75 |

| Piperacillin-TZB | 0.38 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Cephalothin | >256 | >256 | 6 |

| Cefepime | 0.032 | 0.75 | 0.032 |

| Cefotaxime | 2 | 1 | 0.064 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.064 | 1 | 0.19 |

| Aztreonam | 1.5 | 64 | 0.19 |

| Meropenem | >32 | 0.38 | 0.008 |

| Imipenem | >32 | 4 | 0.125 |

CLA, clavulanic acid; TZB, tazobactam.

Chromosomal location of class A β-lactamases in S. fonticola UTAD54.

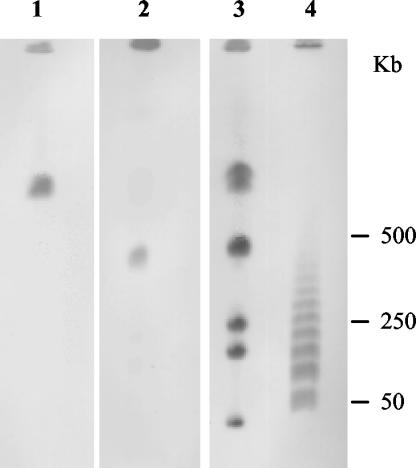

DNA from S. fonticola UTAD54 embedded in agarose was digested with I-CeuI (New England Biolabs, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom), and the resulting fragments were separated on a CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) (5). Six fragments were generated. After immobilization on nylon membranes, the I-CeuI-generated fragments were hybridized with three different probes: an rRNA gene probe, a probe specific to the naturally occurring class A β-lactamase (SFO-1), and a blaSFC-I probe.

The probes were generated by PCR amplification in the presence of digoxigenin (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). For rRNA genes and the SFO-1 gene, the primers were previously reported (18). Specific primers were designed to amplify the blaSFC-I gene, SfcF (5′-GATCTCGAGAATGTCACGCACCGGTCGACTG-3′), and SfcR (5′-GATGAATTCTTAGAAGCCGATAGACTTTCC-3′). The probes for the SFC-1 and SFO-1 genes revealed two different I-CeuI bands, as shown in lanes 1 and 2 of Fig. 3; the probe for rRNA genes hybridized to the six I-CeuI bands (lane 3). These results thus indicate that both β-lactamase genes are chromosomally encoded and apart from each other. Hybridization of the probe for blaSFC-I with DNA from S. fonticola strains LMG 7882T, DSM 9663, and CIP 103850 did not detect homologous sequences in these genomes.

FIG. 3.

Hybridizations to I-CeuI fragments generated from the genome of S. fonticola UTAD54 and separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, hybridization with SFC-1 probe; lane 2, hybridization with probe for naturally occurring class A β-lactamases of S. fonticola; lane 3, hybridization using a probe for rRNA genes; lane 4, concatemers of phage lambda DNA.

Concluding remarks.

S. fonticola UTAD54 is an exceptional strain, carrying the naturally occurring β-lactamases of S. fonticola and different classes of carbapenemases, SFC-1 and the previously reported metallo-enzyme Sfh-I. Those enzymes are not present in other S. fonticola strains. These exceptional characteristics could be the result of the acquisition of a genetic element by horizontal gene transfer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY354402.

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through grants to Artur Alves (SFRH/BD/10389/2002) and Isabel Henriques (SFRH/BD/5275/2001).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa, Y., M. Ohta, N. Kido, M. Mori, H. Ito, T. Komatsu, Y. Fujii, and N. Kato. 1989. Chromosomal beta-lactamase of Klebsiella oxytoca, a new class A enzyme that hydrolyzes broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:63-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavini, F., C. Ferragut, D. Izard, P. A. Trinel, H. Leclerc, B. Lefebvre, and D. A. Mossel. 1979. Serratia fonticola, a new species from water. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 29:92-101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachapelle, J., J. Dufresne, and R. C. Levesque. 1991. Characterization of the blaCARB-3 gene encoding the carbenicillinase-3 beta-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 102:7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu, S. L., A. Hessel, and K. E. Sanderson. 1993. Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6874-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto, Y., and M. Inoue. 1999. Characterization of SFO-1, a plasmid-mediated inducible class A beta-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:307-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naas, T., and P. Nordmann. 1994. Analysis of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and of its LysR-type regulatory protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7693-7697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naas, T., D. Livermore, and P. Nordmann. 1995. Characterization of an LysR family protein, SmeR from Serratia marcescens S6, its effect on expression of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase Sme-1, and comparison of this regulator with other β-lactamase regulators. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:629-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naas, T., L. Vandel, W. Sougakoff, D. Livermore, and P. Nordmann. 1994. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gene for a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase, Sme-1, from Serratia marcescens S6. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1262-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. NCCLS, Wayne, Pa.

- 11.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordmann, P., S. Mariotte, T. Naas, R. Labia, and M. H. Nicolas. 1993. Biochemical properties of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and cloning of the gene into Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:939-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Péduzzi, J., S. Farzaneh, A. Reynaud, M. Barthélémy, and R. Labia. 1997. Characterization and amino acid sequence analysis of a new oxyimino cephalosporin-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase from Serratia fonticola CUV. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1341:58-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perilli, M., N. Franceschini, B. Segatore, G. Amicosante, A. Oratore, C. Duez, B. Joris, and J. M. Frere. 1991. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the gene encoding the beta-lactamase from Citrobacter diversus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 83:79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfyffer, G. E. 1992. Serratia fonticola as an infectious agent. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:199-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raquet, X., J. Lamotte-Brasseur, F. Bouillenne, and J.-M. Frère. 1997. A disulfide bridge near the active site of carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamases might explain their unusual substrate profile. Proteins 27:47-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmussen, B., K. Bush, D. Keeney, Y. Yang, R. Hare, C. O'Gara, and A. Medeiros. 1996. Characterization of IMI-1 β-lactamase, a class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme from Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2080-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saavedra, M. J., L. Peixe, J. C. Sousa, I. Henriques, A. Alves, and A. Correia. 2003. Sfh-I, a subclass B2 metallo-β-lactamase from a Serratia fonticola environmental isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2330-2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saladin, M., V. T. Cao, T. Lambert, J. L. Donay, J. L. Herrmann, Z. Ould-Hocine, C. Verdet, F. Delisle, A. Philippon, and G. Arlet. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M beta-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seoane, A., and J. M. Garcia Lobo. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of a new class A beta-lactamase gene from the chromosome of Yersinia enterocolitica: implications for the evolution of class A beta-lactamases. Mol. Gen. Genet. 228:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith Moland, E., N. D. Hanson, V. L. Herrera, J. A. Black, T. J. Lockhart, A. Hossain, J. A. Johnson, R. V. Goering, and K. S. Thomson. 2003. Plasmid-mediated, carbapenem-hydrolysing beta-lactamase, KPC-2, in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:711-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sougakoff, W., T. Naas, P. Nordmann, E. Collatz, and V. Jarlier. 1999. Role of Ser-237 in the substrate specificity of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase Sme-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1433:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stock, I., S. Burak, K. J. Sherwood, T. Gruger, and B. Wiedemann. 2003. Natural antimicrobial susceptibilities of strains of “unusual” Serratia species: S. ficaria, S. fonticola, S. odorifera, S. plymuthica, and S. rubidaea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:865-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yigit, H., A. Queenan, G. Anderson, A. Domenech-Sanchez, J. Biddle, C. Steward, S. Alberti, K. Bush, and F. Tenover. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1151-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]