Abstract

Background

Appropriate follow-up care is important for improving health outcomes in breast cancer survivors (BCSs) and requires determination of the optimum intensity of clinical examination and surveillance, assessment of models of follow-up care such as primary care-based follow-up, an understanding of the goals of follow-up care, and unique psychosocial aspects of care for these patients. The objective of this systematic review was to identify studies focusing on follow-up care in BCSs from the patient’s and physician’s perspective or from patterns of care and to integrate primary empirical evidence on the different aspects of follow-up care from these studies.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review and evaluation was conducted for all relevant publications in English from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2013 using electronic databases. Studies were included in the final review if they focused on BCS’s preferences and perceptions, physician’s perceptions, patterns of care, and effectiveness of follow-up care.

Results

A total of 47 studies assessing the different aspects of follow-up care were included in the review, with a majority of studies (n=13) evaluating the pattern of follow-up care in BCSs, followed by studies focusing on BCS’s perceptions (n=9) and preferences (n=9). Most of the studies reported variations in recommended frequency, duration, and intensity of follow-up care as well as frequency of mammogram screening. In addition, variations were noted in patient preferences for type of health care provider (specialist versus non-specialist). Further, BCSs perceived a lack of psychosocial support and information for management of side effects.

Conclusion

The studies reviewed, conducted in a range of settings, reflect variations in different aspects of follow-up care. Further, this review also provides useful insight into the unique concerns and needs of BCSs for follow-up care. Thus, clinicians and decision-makers need to understand BCS’s preferences in providing appropriate follow-up care tailored specifically for each patient.

Keywords: breast cancer, breast cancer survivors, follow-up care, outcomes, survivorship care

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer among women worldwide and its incidence has increased over the past 3 decades in many parts of the world, with approximately 1.7 million new cases diagnosed in 2012.1,2 This accounts for about 12% of all new cancer cases and 25% of all cancers that affect women.1 Furthermore, breast cancer survival has increased significantly due to improvement in diagnosis and treatment programs; women diagnosed with early, node-negative breast cancer now have a 5-year survival of 95%–98%, especially in developed countries.3,4 The significant progress made in prolonging survival after breast cancer treatment has presented new challenges to health care professionals (HCPs) and patients.5 Breast cancer is a long-lasting illness as it presents various post-treatment issues pertaining to cancer and its related treatments, including short- and long-term side effects, comorbidities, and emotional issues (fear of recurrence, late episodes of depression) as well as risk of cancer recurrence.6 Thus, appropriate follow-up care is an important aspect of comprehensive care for breast cancer survivors (BCSs) for improving patient outcomes, including reduced morbidity and mortality, improved psychosocial well-being, quality of life (QoL), and overall patient satisfaction.

The post-treatment follow-up care of BCSs requires determination of the optimum intensity of clinical examination and surveillance, assessment of models of follow-up care, such as primary care-based follow-up, an understanding of the goals of follow-up care, and unique psychosocial aspects of the care for these patients.7 Further, there are well-established guidelines by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and other national and international agencies that provide recommendations for key elements of follow-up care for BCSs.8–12 These guidelines aim to assist HCPs with decision-making for the effective management of BCSs, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Providing routine post-treatment follow-up services to BCSs is a standard practice in most countries.13 However, previous research indicates that there are variations in different aspects of follow-up care, such as the delivery of follow-up care, frequency of breast cancer surveillance, and extent of necessary psychological support and rehabilitation interventions required for reducing comorbidities.14–17 Further, there is no evidence on how these variations in follow-up care impact patient outcomes such as morbidity and mortality. In addition, it is also important to understand how patients perceive follow-up care and identify the unmet needs of these patients as well as physicians’ perceptions of follow-up care and their recommendations for improving patient outcomes.

Thus, the overall objective of this systematic review was to identify studies focusing on follow-up care in BCSs from the patient’s and physician’s perspective or from patterns of care and to integrate primary empirical evidence on the different aspects of follow-up care from these studies. The specific objectives were: 1) to identify studies focusing on aspects of follow-up care in BCSs including BCS’s preferences and perceptions, physicians’ perceptions, patterns of care, and effectiveness of follow-up care and 2) to identify components for optimal follow-up care that might be helpful in addressing unique needs and preferences of BCSs.

Methods

Search strategy

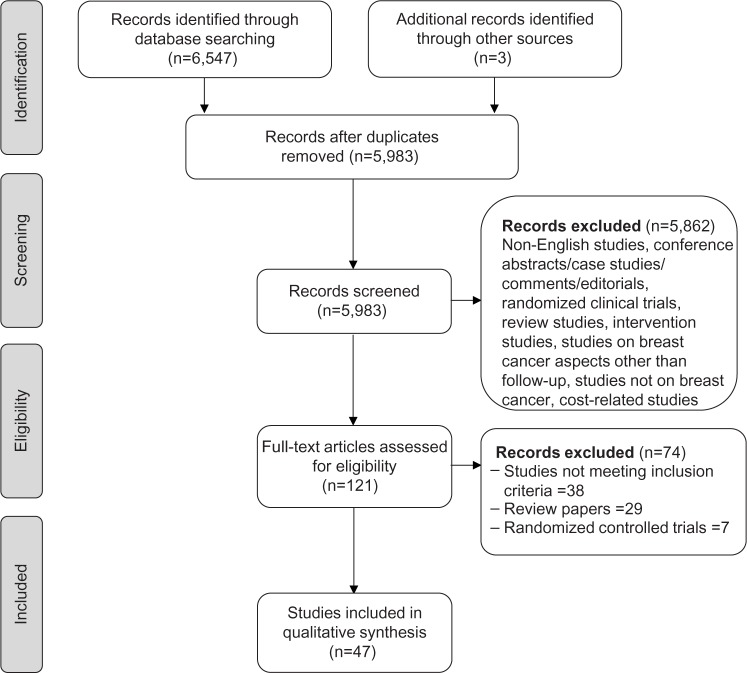

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,18 a systematic literature search was conducted from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2013. The literature search was conducted using electronic databases including PubMed, psychINFO, Embase, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search strategy included combinations of keywords related to breast cancer and follow-up care such as breast cancer, breast neoplasm, breast carcinoma, BCS, post-treatment, follow-up, follow-up care, surveillance, survivorship care, screening, monitoring, pattern of care, and clinical care. Stage 1 screening identified titles or abstracts related to the main topic of interest. Furthermore, bibliographies of selected articles and published reviews were screened for additional studies of relevance. Titles and abstracts reviewed in Stage 1 were screened against the inclusion criteria, described below, in Stage 2. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were then subjected to final review. The literature search process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of methodology used and selection criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was limited to studies in English language. The inclusion of studies was limited to only breast cancer; studies on cancer in general were excluded. Randomized clinical trials, review studies, and intervention studies were excluded. In addition, conference abstracts, dissertations, summary reports, case studies, commentaries, and editorials were also excluded. Articles were included in the final review if they focused on BCS’s preferences and perceptions, physicians’ perceptions, patterns of care, and effectiveness of follow-up care. For the purpose of this review, breast cancer survivorship was defined as the period following first diagnosis and curative treatment and before recurrence of cancer or death;6 studies on patients undergoing treatment were excluded.

Data extraction

For the studies evaluating follow-up care in BCSs, the following information was extracted: study purpose, country where the study was conducted, population characteristics (sample size, patient’s age, time since diagnosis, type of primary breast cancer treatment), study design, and key findings.

Results

Based on the literature search methodology, 47 studies met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were subjected to final review.19–65 The studies focusing on follow-up care in BCSs have been conducted in different populations worldwide, most of them in the US (n=19),27,33–36,41–43,46,53–59,63–65 followed by the UK (n=10),26,31,32,39,40,45,51,52,61,62 and the Netherlands (n=7).23,24,38,44,48,49,60

Regarding study design, survey-based design including questionnaires, interview, or web-based surveys, was the most common study design used for evaluating follow-up care for assessing BCS’s preferences or perceptions as well as physicians’ perceptions regarding follow-up care. Secondary databases including Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare claims data, patient chart reviews, and data from hospital documents were used for evaluating patterns and effectiveness of follow-up care.

For the purpose of this review, results from the studies have been categorized into six groups. These include studies evaluating aspects of follow-up care: i) BCS’s preferences, ii) BCS’s perceptions, iii) HCP’s perceptions, iv) common perceptions of both BCSs and HCPs, v) patterns, and vi) effectiveness.

BCS’s preferences for follow-up care

Table 1 provides a summary of nine studies that evaluated BCS’s preferences for follow-up care.19–27 Most of the studies had moderate-to-large sample sizes ranging 79–465 patients, except for one study22 in which focus group interviews were conducted with 26 patients. These studies were conducted in young, middle, or older-aged individuals, with age ranging from 33–90 years.

Table 1.

Studies evaluating breast cancer survivors’ preferences for follow-up care

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiwa et al24 | Preference for surveillance follow-up | Australia | N=101; mean age =62.2 yrs Mean time since treatment =3.8 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or lumpectomy |

Questionnaire-based survey | 68% of women consulted BCN about breast cancer-related symptoms. Patients preferred their GP if they needed a physical examination/referral to a specialist. Older patients preferred BCN for mammogram and GP if they needed a physical exam or emotional support. |

| Pauwels et al21 | Care needs of rehabilitating BCSs | Belgium | N=465; mean age =51.9 yrs Time since diagnosis =3 weeks–6 months Treatment = breast-conserving, mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy |

Questionnaire-based survey | High unmet needs were reported across physical and psychosocial functioning. Younger age and lower income were associated with care needs after treatment. |

| Singh-Carlson et al27 | Preferences of South-Asian BCSs regarding follow-up care | Canada | N=24; mean age =55.5 yrs Time since treatment =4–47 months Treatment = surgery alone or with chemotherapy, radiation, or hormonal therapy |

Focus groups and semi-structured interviews | Patients preferred generalized SCP with individualized content. Younger women preferred information on depression and social support. |

| Smith et al23 | Patient preferences for survivorship care | Canada | N=26; mean age =59.2 yrs Time since treatment =3–12 months |

Qualitative study design using focus group sessions | Preferred follow-up care elements included treatment summary, information on nutrition/exercise, expected side effects, signs and symptoms of recurrence, recommended follow-up schedule, information sent to PCP, and updates on changes. BCSs had preference for individualized content depending upon physical and psychosocial effects. |

| De Bock et al20 | BCS’s needs and preferences for follow-up care | the Netherlands | N=84; median age =56 yrs Median time since treatment =3 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy |

Cross-sectional survey | Patients preferred additional investigations (such as X-ray and blood tests) to be part of routine follow-up visits and preference for a more intensive follow-up schedule. |

| Kimman et al25 | Patient preferences for follow-up care | the Netherlands | N=331; mean age =58 yrs Treatment = surgery with or without radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or both |

Data were collected by survey | Medical specialist was most preferred for follow-up; face-to-face contact was strongly preferred to telephone contact; follow-up visits every 3 months were preferred over visits every 4, 6, or 12 months. |

| Stemmler et al22 | Patients’ perspective on follow-up care for breast cancer | Germany | N=452; mean age =62 yrs | Questionnaire-based survey | Need for surveillance was reported by a majority of patients (>95%), and one-third reported need for more technical efforts during follow-up. |

| Montgomery et al19 | Patients’ expectations for follow-up in breast cancer | UK | N=79; mean age =59 yrs | Questionnaire-based survey | Expectations for length and frequency varied dramatically. Most believed follow-up is for the detection of relapse, but very few saw psychological support or side effect detection as being central to clinicians’ aims. |

| Mayer et al26 | BCS’s comfort with different components of survivorship care | US | N=218; median age =57.5 yrs Treatment = surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or endocrine therapy |

Cross-sectional survey | Patients preferred medical oncologist over PCPs or NPs in terms of reduced worrying about cancer, reduced stress around the visit, and improved effect on cancer survival; preferred in-person visits with clinicians. |

Abbreviations: BCN, breast cancer nurse; BCS, breast cancer survivor; GP, general practitioner; NP, nurse practitioner; PCP, primary care physician; SCP, survivorship care plan; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; yrs, years.

Two studies examined the BCS’s preferences for HCP, where medical specialists were favored over non-specialists (for example, oncologist over primary care physician [PCP]).24,27 Mayer et al reported that follow-up visits to medical oncologists were preferred over PCPs or nurse practitioners for domains including reduced worry about cancer (odds ratio [OR]: 2.21; P<0.001), reduced stress around the visit (OR: 1.40; P<0.002), and improved effect on cancer survival (OR: 2.38; P<0.001).26 Further, Jiwa et al reported that older patients preferred a breast cancer nurse (BCN) for a mammography and a general practitioner for physical exam or emotional support.24

Besides preference for HCP, availability of information on concerns such as long-term effects of treatment, nutrition/exercise, recurrence, and recommended follow-up schedule, was also a key element in survivorship care.21,22,26 In addition, BCS’s preferences included in-person visits to physicians versus virtual visits and individualized content-based follow-up on physical and psychosocial effects.21,22,24,27 Further, a need for more intensive therapy was reported by patients who received adjuvant hormonal therapy.23,25

BCS’s perceptions of follow-up care

Table 2 provides a summary of nine studies that assessed BCS’s perceptions of follow-up care.28–36 Most of the studies had small sample sizes, ranging from 10–41 patients, except for two studies33,34 that had large sample sizes, ranging from 182–300 patients. Most of the population comprised middle-or older-aged individuals, with age ranging 49–61 years.

Table 2.

Studies evaluating breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of follow-up care

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brennan et al28 | BCS’s experiences with current follow-up care | Australia | N=20; age =40–59 yrs Time since treatment =2–5 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy |

Semi-structured telephone interviews | Women attended follow-up visits with a specialist oncologist and reported a high level of satisfaction with care. Communication between multidisciplinary team members was perceived as an ongoing problem. |

| Lawler et al29 | Explore and examine experiences and perceptions of follow-up care | Australia | N=25; mean age =49 yrs Mean time from diagnosis =2.5 yrs Treatment = surgery with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy |

Telephone interview | Majority of women perceived a marked decline in the quality and duration of follow-up consultations with clinicians; considerable overlap in follow-up care when multiple providers were involved; lack of psychosocial support; limited availability of medical providers in rural areas. |

| Singh-Carlson et al34 | Perceptions of South-Asian BCSs regarding follow-up | Canada | N=64; age =18–85 yrs Time since treatment =3–60 months |

Survey | Fewer patients (37%) understood the meaning of follow-up care. Most of the patients (59%) were satisfied with follow-up care. |

| Pennery and Mallet33 | Patients’ perceptions of routine follow-up care | UK | N=24; mean age =51 yrs Mean time since treatment =28 months |

Cross-sectional survey | Follow-up examinations were hurried, investigations were not reassuring, and that the lack of continuity was unacceptably poor. Majority of patients felt uncomfortable asking questions and expressing emotional concerns. |

| Renton et al30 | Patient perceptions for follow-up care | UK | N=41; mean age =59.9 yrs Mean time since diagnosis =3.94 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, wide local incision, others |

Cross-sectional survey | Eighty-four percent considered follow-up important and most women were satisfied with follow-up practice, frequency, and duration of appointments; nurse-led system of follow-up. Risk of recurrence and effects of treatments were considered important for discussion. |

| Mallinger et al35 | BCS’s satisfaction with information | US | N=182; mean age =58.0 yrs Mean time from diagnosis = <1 to >5 yrs Treatment = surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy |

Questionnaire-based survey | BCSs were less satisfied with information related to the long-term physical, psychological, and social sequelae of the disease and its treatments. Patients’ perception of patient-centered behaviors was strongly associated with patients’ satisfaction with information. |

| Mao et al32 | BCS’s perceptions of PCP-related survivorship care | US | N=300; mean age =61 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy |

Cross-sectional survey | Areas of PCP-related care most strongly endorsed were general care, psychosocial support, and health promotion. Fewer BCSs perceived their PCPs as knowledgeable about cancer follow-up, late effects of cancer therapies, or treating symptoms related to cancer or cancer therapies. |

| Royak-Schaler et al31 | Patient–physician communication for developing survivorship care | US | African-American BCSs, N=39; age =30–75 yrs Treatment =0–5 yrs Treatment = surgery with or without chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both |

Qualitative study design using focus group sessions and survey | Patients reported gaps in the information provided by HCPs about their diagnosis, treatments, side effects, and guidelines for follow-up care. More than 90% of participants reported a lack of specific recommendations regarding diet or physical activity as ways to improve QoL and health. |

| Thompson et al36 | Post-treatment follow-up care experiences of African-American BCSs | US | N=10; mean age =50.2 yrs Time since treatment =1–6 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy with chemotherapy or radiotherapy |

Exploratory and qualitative study conducted using interviews | Factors motivating BCSs in obtaining follow-up care: desire to maintain good health, concern about recurrence, support from health care providers, familial relationships, relationships with other survivors, and spiritual faith. Barriers to care: fear of recurrence, low support from family/friends, lack of information about post-treatment follow-up care, and medical care costs. |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast cancer survivor; HCP, health care professional; PCP, primary care physician; QoL, quality of life; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; yrs, years.

Two studies evaluated perceptions of Australian BCSs, where considerable overlap in follow-up with a multidisciplinary team of health care providers was perceived as an ongoing problem.28,29 In addition, inadequate interdisciplinary communication perceived by BCSs was reported by Mao et al.32 Further, two studies focused on perceptions of African-American BCSs, in which lack of information about post-treatment care was one of the barriers to follow-up care.35,36 Other impediments to follow-up care included, but were not limited to, fear of recurrence, lack of social support, and medical care costs.36 In addition, the study by Pennery et al reported that most of the patients perceived a lack of continuity in follow-up care, felt uncomfortable expressing emotional concerns, and were not satisfied with physical examinations.33

Further, examining patients’ perceptions of quality of care, a report from Mao et al analyzed BCS’s perceptions of PCP’s survivorship care; 50%, 59%, and 41% of patients perceived their physicians as knowledgeable about cancer follow-up, late effects of cancer therapies, and treating symptoms related to cancer or cancer treatments, respectively. Only 28% indicated that there was adequate communication between their PCP and their specialist.32

Perception of HCPs regarding BCS’s follow-up care

Table 3 summarizes seven studies focusing on the perception of HCPs regarding follow-up care.37–43 In these studies, HCPs perceived follow-up care as important for the detection of treatment-related morbidity,37,39 need for greater care coordination across institutions,41 and need for sustainability of follow-up care in their practices.37 In addition, these studies also provide insight into the current practices as reported by HCPs. For example, a survey of ASCO members reported variations in intensity of post-treatment surveillance, such as overuse of surveillance testing (blood tests, liver function tests) not recommended by ASCO guidelines.42,43 A study on Australian HCPs noted that about one-third of the specialists reported that follow-up intervals and duration were in accordance with the national guidelines.37 Similar results were reported by studies evaluating perceptions of HCPs on follow-up care practices in the Netherlands and the UK.39,38

Table 3.

Studies evaluating perception of health care professionals regarding breast cancer survivors’ follow-up care

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brennan et al37 | Attitudes of HCPs to current models of follow-up care | Australia | N=217 Specialist oncologists (surgeons, medical, and radiation oncologists), breast physicians, and breast care nurses |

Cross-sectional online survey | Viewed follow-up care as an important part of their clinical role but expressed concern about the sustainability of follow-up care in their practices. Reported that follow-up was in line with national guidelines; supported sharing follow-up care with other HCPs; supported SCP. |

| Van Hezewijk et al41 | Professionals’ opinions on BC follow-up | the Netherlands | N=130 Surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, nurse practitioner |

Web-based survey | Eighty-one percent of HCPs follow current national guidelines and all different specialists are involved in follow-up. For tailored follow-up, professionals indicate more factors for increased follow-up (age <40 years, pT3–4 tumor, pN2–3, treatment-related morbidity, and psychosocial support). |

| Donnelly et al43 | Attitudes of health care specialists to follow-up care | UK | N=562 Surgeons, clinical oncologists, medical oncologists, oncologists of unknown specialty, and general medical consultants |

Questionnaire-based survey | Most commonly acknowledged purpose of follow-up was detection of treatment-related morbidity. Eighty-four percent of HCPs adhered to a locally developed protocol with only 9% conforming to NICE guidelines. |

| Smith et al40 | Perception of PCPs for follow-up care | UK | N=590 PCPs |

Survey | PCPs reported being more confident in screening for recurrence and managing patient anxiety and were least confident in managing lymphedema and providing psychosocial support. |

| Hahn et al38 | Provider perceptions and expectations of post-treatment breast cancer care | US | N=39 Medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgeons, oncology nurses, and PCPs |

Interview | Perceived need for greater care coordination across institutions and within oncology, for improving delivery of post-treatment health care services and avoiding duplication of follow-up care and services, respectively. Survivorship care programs were perceived as important for improving care delivery. |

| Margenthaler et al42 | Perceptions of follow-up care | US | N=915 ASCO members with breast cancer as a major focus of their practice; specialty: surgical, radiation, or medical oncology and others |

Survey | Office visit, mammogram, complete blood count, and liver function tests were the most commonly recommended surveillance modalities. Intensity of post-treatment follow-up surveillance varied and many screening tests not recommended by ASCO were commonly used. |

| Parmeshwar et al39 | Perceptions of surveillance testing among BCSs | US | N=846 ASCO members with breast cancer as a major focus of their practice; specialty: surgeons, radiation, or medical oncologists and others |

Survey | Variations in the frequency of recommended use of office visits, mammography, and other tests such as liver function tests were reported. |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; BC, breast cancer; BCS, breast cancer survivor; HCP, health care professional; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PCP, primary care physician; SCP, survivorship care plan; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Perceptions of both BCSs and HCPs regarding follow-up care

Table 4 summarizes three studies focusing on both BCS’s and HCP’s opinion on follow-up care.44–46 These studies highlight components of follow-up care that are commonly perceived by BCSs and HCPs. For instance, for both patients and HCPs, the detection of recurrence was the most important purpose of follow-up.45 Further, both HCPs and African-American BCSs considered written survivorship care plans helpful for follow-up care.46

Table 4.

Studies evaluating perceptions of both health care professionals and breast cancer survivors regarding follow-up care

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwast et al45 | Opinions and preferences for follow-up care | the Netherlands | BCSs =23 HCPs =18 |

Semi-structured interviews | For both patients and HCPs, early detection of new malignancies was the most important purpose of follow-up. A highly valued aspect mentioned by HCPs was the psychosocial support. Patients and HCPs were positive about NP-led follow-up versus GP-led follow-up. |

| Beaver and Luker46 | Nature and content of follow-up visits following completion of breast cancer treatment | UK | BCSs: N=104 HCPs: N=14 |

Direct observations, patient surveys, and audio-recording of consultations with HCPs | Consultations were focused on detection of recurrence, were generally of brief duration (mean 6 minutes), and were overwhelmingly optimistic. Few opportunities to meet information and psychosocial needs were available. |

| Kantsiper et al44 | Needs and priorities of BCSs, oncology specialists, and PCPs concerning breast cancer survivorship care | US | BCSs =21 PCPs =15 Oncology specialists =16 |

Qualitative analysis using focus groups | Many BCSs believed PCPs lacked required oncology expertise and there were psychosocial and communication issues. PCPs were concerned about lack of adequate time and training to provide survivorship care and presence of communication problems with oncologists. Written survivorship care plans were preferred by both BCSs and PCPs. |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast cancer survivor; GP, general practitioner; HCP, health care professional; NP, nurse practitioner; PCP, primary care physician; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Patterns of follow-up care in BCSs

Table 5 summarizes 13 studies assessing the patterns of follow-up care in BCSs.47–59 Five studies examined the pattern of mammography utilization or surveillance testing in the US population consisting of older BCSs (≥65 years) during follow-up.53–58 Most of the patients (82%) had a mammography during the first year after treatment; the percentage declined to 68.5% by the fourth year of follow-up.54 Similarly, visits to a medical oncologist also declined after year 1; the percentage of patients seeing a medical oncologist decreased from 50% in year 1 to 27% by year 3.57 One of the studies noted that women visiting a medical oncologist (breast cancer surgeon: OR: 6.0; 95% CI: 4.9–7.4 and oncologist: OR: 7.4; 95% CI: 6.1–9.0) were more likely to receive a mammography compared to visits to PCPs.54 Further, Etim et al reported that women who had follow-up visits with both generalists and breast cancer specialists were more likely to receive a mammography versus those seeing only one HCP (OR: 2.13; 95% CI: 1.74–2.58).50

Table 5.

Studies evaluating pattern of follow-up care in breast cancer survivors

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grunfeld et al59 | Patterns of follow-up care | Canada | N=11,219; mean age =60.1 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, lumpectomy, or other surgery |

Retrospective longitudinal study | Two-thirds had either fewer or greater than recommended oncology visits, one-quarter had fewer than recommended surveillance mammograms, and half had greater than recommended surveillance. |

| Grandjean et al47 | Adherence with follow-up criteria as suggested by the national guideline | the Netherlands | N=196; mean age =57.5 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy |

Data collected from database of the Netherlands Cancer Registry | Fewer consultations were performed in the first year of follow-up than in the second through to the fifth year compared to guideline standards. Physical examinations were performed during 97% of consultations, but mammograms were performed slightly less often. |

| Lu et al54 | Utilization of long-term routine hospital follow-up care | the Netherlands | N=662; median age =57.7 yrs Type: mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery with or without chemotherapy or hormone therapy |

Information was obtained from hospital documents | At fifth and tenth years after diagnosis, patients had fewer follow-up visits and less frequent mammographies than recommended in the national guideline. Less frequent mammography was found in older patients, those with comorbidity, and those taking hormonal therapy. |

| Baena-Canada et al52 | Follow-up care difference based on attention received, ie, primary or specialist service | Spain | BCSs seeking 1) primary care: N=60, mean age =65.7 yrs; 2) specialist care: N=38, mean age =58.5 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, breast-conserving therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy |

Retrospective cohort study | No differences in HRQoL or diagnosis of metastasis/new primary tumors were observed for patients seeking primary or specialist services. Patients had higher preference for and greater satisfaction with specialist care. |

| Green-Haigh51 | Practice of use of mammographic surveillance in the follow-up care | UK | N=32 Treatment = surgery |

Questionnaire-based survey | Duration of mammography for patients aged ≥70 years surgically treated by mastectomy demonstrated the greatest diversity. |

| Worster et al58 | Pattern of follow-up care | UK | N=183 | Patient charts were reviewed for data collection | Follow-up care during the 5-year postoperative period was provided in most cases by oncologists alone (66.7%). Surgeons were more likely to provide care for patients who received radiation treatment. |

| Etim et al50 | Receipt of mammography among BCSs during follow-up care based on service type | US | N=3,828; age ≥66 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy without radiation therapy |

SEER database was linked to US 1990 Census files and Medicare claims data | About two-thirds of patients underwent shared care (both generalist physician and specialist services) during first 3 yrs after treatment. Women receiving shared care had substantially greater mammography use than others. |

| Field et al56 | Use of mammography during follow-up care in BCSs | US | N=1,762; age ≥65 yrs Treatment = mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy with or without radiation therapy |

Data collected from cancer registry, administrative, clinical databases, and patient medical records | Percentage of women receiving mammograms declined from first year after treatment (82%) to fourth year of follow-up (68.5%). Women with visits to a breast cancer surgeon or oncologist were more likely to receive mammograms. |

| Hahn et al48 | Use of imaging and biomarker tests for follow-up | US | N=258; mean age =58 yrs Mean time since diagnosis =6 yrs |

Claims data and medical records | Forty-seven percent of patients received mammogram within 1 year of diagnosis, 55% received at least one non-recommended imaging test, and 74% received biomarker tests. |

| Keating et al49 | Underutilization of surveillance mammography among BCSs | US | N=44,511; age ≥65 yrs Time since diagnosis ≥7 months Treatment = mastectomy or lumpectomy |

Retrospective cohort study using data from the SEER registry linked to Medicare claims | Women who were older, black, unmarried, and living in certain regions were less likely than other women to undergo surveillance mammography. |

| Keating et al53 | Pattern of surveillance testing among BCSs | US | N=44,511; age ≥65 yrs Time since diagnosis ≥7 months Treatment = mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery with or without radiotherapy, other |

Retrospective cohort study using data from the SEER registry linked to Medicare claims | Nearly half of BCSs saw a medical oncologist in surveillance year 1, which reduced to 27% annually at 3 years. Women seeing medical oncologists had more bone scans, tumor antigen testing, chest X-rays, and chest/abdominal imaging. |

| Onega et al55 | Pattern of surveillance breast imaging and biopsy in older BCSs | US | N=1,219; age =65–80 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, BCS with or without radiotherapy, other |

Data from a state-wide (New Hampshire) breast cancer screening registry linked to Medicare claims was used | The proportion of women with mammography was high over the follow-up period (81.5% at 78 months). |

| Schapira et al57 | Mammography utilization in older BCSs | US | N=3,885; mean age =74.0 yrs Treatment = mastectomy, BCS with or without radiotherapy |

Retrospective cohort study using data from the SEER registry linked to Medicare claims | Sixty-two percent of the cohort underwent annual mammography. Use of annual mammography was significantly lower among women treated with mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery without radiotherapy than among women with radiotherapy. |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast cancer survivor; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; yrs, years.

Eight studies examined the pattern of surveillance in women aged ≥20 years.47–52,55,59 One study reported that the number of consultations among women who underwent radiotherapy were significantly higher (P<0.01) from second through to the fifth year compared to that in the first year and mammography was performed during 97% of consultations.48 However, another study reported a decrease in the number of follow-up visits and mammography, where at fifth year, follow-up visits declined to 16.1%, and 33.1% had fewer than the recommended number of mammogram screenings; decline in mammography was reported in older patients (age >70 years; OR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.62–2.74), patients with comorbidity (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.05–1.52), and patients who underwent hormone therapy (OR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.01–2.25).49 Regarding health care provider, the majority of women had follow-up visits to both oncologists and PCPs.47

Effectiveness of follow-up care in BCSs

Table 6 summarizes six studies assessing the effectiveness of follow-up care in BCSs, where each study evaluated a different outcome including mortality, detection of recurrence, increase in surveillance testing, and reduction in anxiety.60–65 For example, the results of two studies showed that surveillance mammography was effective in reducing breast cancer mortality.63 However, one study noted that routine follow-up after curative treatment was inefficient in the detection of recurrence.61 These findings suggest that effectiveness of follow-up care components remains uncertain.

Table 6.

Studies evaluating effectiveness of follow-up care in breast cancer survivors

| Study | Purpose | Country | Population | Study design | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geurts et al60 | Efficiency of follow-up care | the Netherlands | N=6,509; median age =58 yrs Treatment = surgery with or without radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy |

Data was obtained from NCR | To detect one locoregional recurrence or second primary breast cancer preclinically, 1,349 physical examinations, 262 mammographies were performed. |

| Morris et al61 | Benefits of routine breast cancer follow-up | UK | N=402; median age =62 yrs Treatment type = mastectomy with or without adjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or tamoxifen |

Questionnaire-based survey | Most women (81%) reported that they felt reassured and less anxious having attended the breast clinic. Routine follow-up after potentially curative treatment of BC was inefficient in the detection of recurrence. |

| Snee64 | Outcome of routine breast cancer follow-up | UK | N=106; mean age =57 yrs Treatment = mastectomy |

Patient records from Yorkshire Regional Centre for Cancer Treatment | At 26 routine clinic visits, a diagnosis other than recurrence of breast cancer was made. Routine follow-up of women treated for breast cancer by mastectomy has limited value. |

| Lash et al63 | Effectiveness of mammography surveillance in follow-up care | US | N=1,846 Time since treatment ≤5 yrs Treatment = surgery with or without chemotherapy, tamoxifen, or both |

Data were collected from medical record review and SEER database | Each additional surveillance mammogram was associated with a 0.69-fold decrease in the odds of breast cancer mortality. |

| Maly et al65 | Involvement of PCPs on the receipt of preventive follow-up care among low-income BCSs | US | N=579; mean age =51.2 yrs Time since treatment ≤3 yrs |

Longitudinal observational study, data obtained from longitudinal surveys of low-income women | Women with a PCP visit only or both PCP and surgeon/cancer specialist visits were more likely to have had annual mammography than those who only visited surgeons/cancer specialists. |

| Nurgalieva et al62 | Effect of surveillance mammography on racial disparities in disease-specific and overall survival in BCSs | US | N=28,117; age >66 yrs Time since diagnosis ≥30 months Treatment = breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy |

SEER–Medicare data | Women who had a mammogram within 1 year were 46% less likely to die from any cause compared with women who did not have any mammograms. |

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; BCS, breast cancer survivor; NCR, the Netherlands Cancer Registry; PCP, primary care physician; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; yrs, years.

Discussion

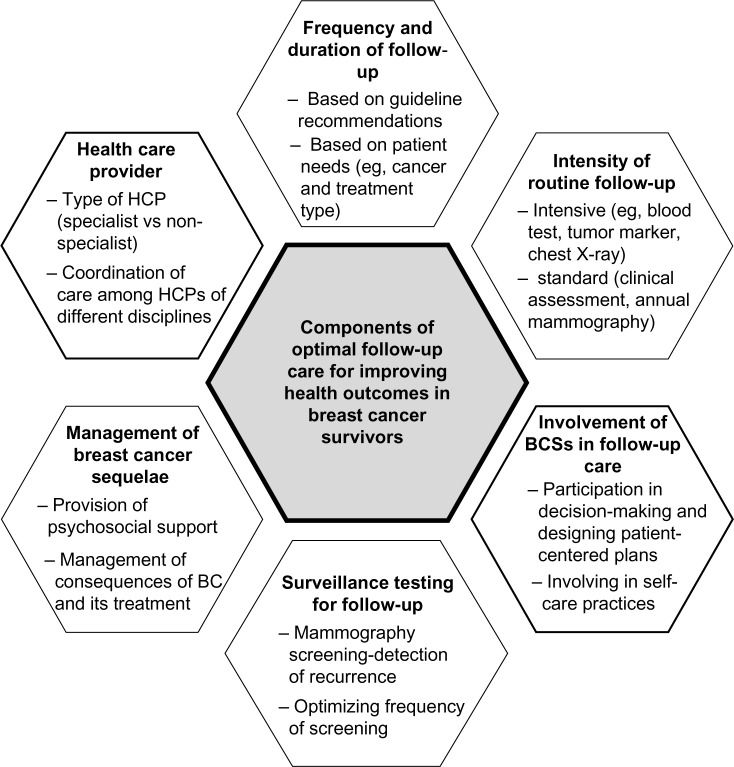

Based on the 2012 World Health Organization report on breast cancer statistics, there were about 6.3 million women alive who had been diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 5 years.66 A steady increase in this number may place a significant burden on the medical community responsible for post-treatment follow-up care in providing optimal care and meeting BCS’s expectations to improve survivorship outcomes. In order to optimize post-treatment follow-up care, it is important to understand the goals of follow-up, including monitoring and managing short- and long-term cancer and its treatment-related side effects, detection of local, regional, and/or systemic recurrence, diagnosis of new primary breast cancers or other cancers, and psychosocial survivorship support.8,14 The challenge to the medical community is to objectively provide follow-up care to a diverse population with variable needs, ie, evidence-based follow-up that improves patient outcomes. There are practice guidelines for follow-up care that provide recommendations on follow-up care components including intensity, length, and frequency of follow-up care, surveillance testing for breast cancer, and coordination of care. However, these guidelines do not account for the individual variations among patients and cannot substitute for the independent professional judgment of a clinician. Thus, each of these components of follow-up care discussed below vary with individual needs and it is difficult to assess the importance of one component over another. This review summarizes evidence reported in the past 24 years that may help in understanding different components of follow-up care (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Components of optimal follow-up care for breast cancer survivors.

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; HCP, health care professional.

Intensive versus standard follow-up care

Intensive follow-up includes various tests, such as full blood count, biochemical assessment, tumor marker CA15-3, chest X-ray, and regular liver ultrasound and bone scan, whereas standard follow-up refers to clinical assessment and annual mammography.17 Generally, intensive follow-up is not recommended by the guidelines and there is no evidence demonstrating that it improves survival, QoL, or reduction in morbidity.7,13,17 Further, it has been suggested that QoL is negatively affected by invasive procedures used in intensive follow-up, possibly because of over-treatment and anxiety resulting from false-positive test results.15 However, studies included in this review suggest that intensive follow-up is frequently used. For instance, ASCO members reported that complete blood count and liver function test were most commonly recommended alongside routine clinical assessment.42,43 Further, receipt of adjuvant hormonal therapy or radiotherapy was associated with a more intensive follow-up, as suggested by one of the studies. In addition, intensive follow-up was also reported to be influenced by factors such as patient preferences, treatment, or clinical factors.23,25 Further research is needed for understanding the factors that affect the decision of standard versus intensive care.

Frequency and duration of follow-up care

Both HCPs and BCSs view follow-up visits to be important for early detection of recurrence.45 In addition, BCSs also expect management of ongoing problems related to cancer or its treatments and availability of psychosocial support.24,26,27 Studies included in this review also suggest a variation from standard follow-up care recommended by guidelines and note various factors such as type of primary treatment, breast cancer stage, and patient’s age that influence the frequency of follow-up services. Based on the findings of this review, it appears that the periodicity of visits should be individually tailored to the observed timings of recurrence, with the goal of diagnosing local, regional, or systemic recurrence in combination with individual needs, including type of cancer, type of primary treatment received, the patient’s medical history, and overall health, including possible treatment-related problems. The Canadian Medical Association also recommends that the frequency and length of the follow-up service should be tailored to meet the needs of individual patients with at least one visit every 12 months. However, the data to address the optimal frequency of follow-up visits is limited. This necessitates further research to ascertain the optimal frequency and duration of follow-up visits and under what circumstances these components can vary.

Type of HCP for providing follow-up care

The evaluation and management of post-treatment follow-up of the patient with breast cancer generally involves HCPs of several disciplines including a PCP, BCN, and medical oncologist. Follow-up with multiple physicians is not only costly, but results in duplication of effort, and has not been shown to improve outcomes.16 Further, patients managed by a multidisciplinary team of HCPs perceived a significant overlap in follow-up care because of the lack of communication in the multidisciplinary care setting. Thus, for effective follow-up care and to improve patient outcomes, there should be coordination among HCPs of different disciplines.

Besides coordination of care, another important aspect is the specialist versus non-specialist model of follow-up care. Given the number of women treated for breast cancer, the frequency of recommended follow-up visits, and the limited availability of resources such as time and specialists, follow-up care after primary treatment of breast cancer is a major activity in departments such as medical oncology, and surgical or radiation oncology.14,16 Therefore, non-specialist-led follow-up care has been proposed as an alternative to specialist care for post-treatment management of cancer patients.14 However, there is little empirical evidence to address this controversy regarding specialist- versus non-specialist-led follow-up. Few studies included in this review have focused on this aspect, which suggests that specialist-led follow-up care was favored over non-specialist care and that fewer patients perceived their PCPs as having adequate knowledge of cancer follow-up and management of cancer-related side effects. Thus, the patient’s preference for a particular type of follow-up (ie, specialist versus non-specialist) should be taken into consideration in formulating a follow-up care plan. If a patient needs to be transferred from a specialist to a non-specialist, there should be clear recommendations for follow-up and in case of evidence of recurrent disease or specific concerns, there should be a way for referral back to the specialist.14

Further studies should evaluate the factors underlying patient’s preferences for follow-up and compare the effectiveness of care provided by different HCPs by assessing outcomes such as patient satisfaction, morbidity, and mortality. It is also important to identify the training needs of non-specialist HCPs to deliver quality follow-up care, thereby improving patient satisfaction with non-specialist-led follow-up care.

Involvement of BCSs in follow-up care

As discussed earlier, the purpose of follow-up care is not only the detection of recurrence, but also to meet patients’ expectations for follow-up. The long-term sequelae of breast cancer and its treatment necessitate the management of related side effects and complications. Our review findings suggest that patients have certain expectations regarding the availability of information on concerns such as short- and long-term physical effects of cancer and psychosocial support, which require the involvement of patients in decision-making. One study investigated the effect of patient-driven decision-making in follow-up care; patients with more involvement in decision-making reported better QoL.13 Thus, involvement of patients in decision-making can be useful in designing patient-centered care plans, thereby improving patient satisfaction and outcomes. Additionally, provision of necessary information can help patients make informed decisions as well as reduce post-treatment morbidity by involving themselves in self-care practices such as breast self-examinations. One of the studies examining preferences of African-American BCSs reported that the study subjects expected evidence-based information and guidelines from their HCP and expressed strong interest in self-care practices aimed at early detection of recurrence.35 However, there is a lack of published evidence focusing on the extent of patients’ involvement in decision-making. Further research focusing on the involvement of patients in decisions about their follow-up care and its impact on patient outcomes is needed.

Surveillance testing for breast cancer follow-up care

Women with a history of breast cancer are at an increased risk of development of contralateral breast cancer (CBC).16 Mammographic screening is the cornerstone of surveillance, especially for CBC and recommended by guidelines as an effective method for the detection of breast cancer at an early stage.13,16 The studies included in this review shed light on the variations in mammographic screening and suggest that there is underutilization of this screening in certain groups of patients. One of the studies reported that underutilization of mammography was more likely in women who are older, of black or Hispanic ethnicity, and in patients not seeing a medical oncologist. Certain barriers to follow-up care have been reported in African-American BCSs, which include fear of recurrence, lack of social support, and medical care costs.57 Additionally, findings from these studies suggest that the majority of patients had either fewer or greater than the recommended number of surveillance mammographies, indicating a variation from guidelines.

Detection of recurrence at a later stage could result in a higher rate of mortality. Thus, in order to improve patient outcomes, it is important to understand the underlying reasons for these variations to optimize the frequency of surveillance testing.

Provision of psychosocial support in follow-up care

Psychological support and reassurance for the patient by their HCP is one of the important primary goals of follow-up care. There are two important psychosocial issues that BCSs face; one is how cancer diagnosis and treatment affects their immediate family and their social relationships and second is how it affects the woman’s own identity (self-concept, body image, and sexuality), which results in problems such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. HCPs can provide emotional and social support by assessing their emotional status at each visit, addressing their fear and concerns, and providing information on patient counseling and arranging referrals. Additionally, BCSs can have social support from their family and friends, peer support programs, telephone support programs, and psycho-educational groups. However, there is a lack of evidence on the type of psychosocial support available to patients and the role of HCPs in providing psychosocial support during follow-up care and its effect on patient outcomes or QoL. A few studies have focused on patient perceptions of follow-up care, where most of the patients perceived a lack of continuity in follow-up care, lack of psychosocial support, and felt uncomfortable expressing emotional concerns. It is likely that provision of psychosocial support or lack thereof may, however, indirectly affect patient outcomes by influencing the patient’s choice of HCP, and the frequency and duration of follow-up care.

Management of short- and long-term side effects

Studies included in this review reported that BCSs preferred information on long-term effects of treatment. Findings from these studies also suggest that from a patient’s perspective, diagnosis of side effects was not the central aim of clinicians. Thus, in order to improve QoL, it is important for clinicians to provide adequate information on side effects and complications. Moreover, a patient-centered approach may be helpful in providing robust and uniform follow-up care for all patients as well as reducing cancer and treatment-related morbidity.

Conclusion

The studies reviewed, conducted in a range of settings, reflect variations in different aspects of follow-up care. Given such variations, future research is needed to better understand the complexity of different factors underlying these variations in order to optimize follow-up care. Further, this review also provides useful insight into the unique concerns and needs of BCSs for follow-up care. Thus, clinicians and decision-makers need to understand BCS’s preferences in providing appropriate follow-up care tailored specifically for each patient.

Author contributions

Both the authors contributed equally to this work.

Related authors

Ishveen Chopra and Avijeet Chopra are siblings.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wcrf.org [homepage on the Internet] Breast Cancer. London, UK: World Cancer Research Fund International; [Accessed March 10, 2014]. Available from: http://www.wcrf.org/cancer_statistics/data_specific_cancers/breast_cancer_statistics.php. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan ME, Houssami N. Overview of long term care of breast cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2011;69(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canceraustralia.gov.au [homepage on the Internet] Breast cancer statistics. Surry Hills, Australia: National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC); 2011. [Assessed May 25, 2014]. [updated April 30, 2014] Available from: http://canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-types/breast-cancer/breast-cancer-statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 4.SEER.cancer.gov [homepage on the Internet] SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER); 2011. [Assessed May 25, 2014]. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber LH, Stout NL, Schmitz KH, Stricker CT. Integrating a prospective surveillance model for rehabilitation into breast cancer survivorship care. Cancer. 2012;118(Suppl 8):2201–2206. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt M, Greenfild S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academics Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunfeld E. Optimizing follow-up after breast cancer treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21(1):92–96. doi: 10.1097/gco.0b013e328321e437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5091–5097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson RW, Anderson BO, Bensinger W, et al. National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Practice Guidelines for Breast Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14(11A):33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugi M, Olivotto A, Lees A, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer. 9. Follow-up after treatment of breast cancer. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158(Suppl 3):S65–S70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidelines.canceraustralia.gov [homepage on the Internet] Surry Hills, Australia: Recommendations for follow-up of women with early breast cancer. [Accessed May 26, 2014]. Available from: http://guidelines.canceraustralia.gov.au/guidelines/early_breast_cancer/ch01.php.

- 12.ESMO ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up of primary breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(8):1047–1048. doi: 10.1023/a:1017448816215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins RF, Bekker HL, Dodwell DJ. Follow-up care of patients treated for breast cancer: a structured review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(1):19–35. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winchester DP. Post-treatment surveillance of breast cancer patients in an organized, multidisciplinary setting. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103(4):358–361. doi: 10.1002/jso.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG, Pavlakis G. Follow-up after primary treatment for breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(8):935–940. doi: 10.1080/02841860050215918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peppercorn J, Partridge A, Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Standards for follow-up care of patents with breast cancer. Breast. 2005;14(6):500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatcheressian J, Swainey C. Breast cancer follow-up in the adjuvant setting. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s11912-008-0007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prisma-statement.org [homepage on the Internet] PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement criteria. 2009. [Assessed January 4, 2014]. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

- 19.Montgomery DA, Krupa K, Wilson C, Cooke TG. Patients’ expectations for follow-up in breast cancer – a preliminary, questionnaire-based study. Breast. 2008;17(4):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bock GH, Bonnema J, Zwaan RE, van de Velde CJ, Kievit J, Stiggelbout AM. Patient’s needs and preferences in routine follow-up after treatment for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(6):1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lechner L, Van Hoof E. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors’ associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):125–132. doi: 10.1002/pon.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stemmler HJ, Stieber P, Lässig D, et al. Follow-up for breast cancer – the patients’ view. Breast Care. 2006;1(3):316–319. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SL, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, Payeur N, Wai ES. Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):337–344. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiwa M, Halkett G, Deas K, Meng X. Women with breast cancers’ preferences for surveillance follow-up. Collegian. 2011;18(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimman ML, Dellaert BG, Boersma LJ, Lambin P, Dirksen CD. Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: one strategy fits all? An investigation of patient preferences using a discrete choice experiment. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(3):328–337. doi: 10.3109/02841860903536002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer EL, Gropper AB, Neville BA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care options. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(2):158–163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh-Carlson S, Wong F, Martin L, Nguyen SKA. Breast cancer survivorship and South Asian women: understanding about the follow-up care plan and perspectives and preferences for information post treatment. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(2):e63–e79. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan ME, Butow P, Marven M, Spillane AJ, Boyle FM. Survivorship care after breast cancer treatment – experiences and preferences of Australian women. Breast. 2011;20(3):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawler S, Spathonis K, Masters J, Adams J, Eakin E. Follow-up care after breast cancer treatment: experiences and perceptions of service provision and provider interactions in rural Australian women. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1975–1982. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renton JP, Twelves CJ, Yuille FA. Follow-up in women with breast cancer: the patients’ perspective. Breast. 2002;11(3):257–261. doi: 10.1054/brst.2002.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Gadalla S, et al. Exploring patient-physician communication in breast cancer care for African American women following primary treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(5):836–843. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.836-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):933–938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennery E, Mallet J. A preliminary study of patients’ perceptions of routine follow-up after treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2000;4(3):138–147. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2000.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh-Carlson S, Nguyen SKA, Wong F. Perceptions of survivorship care among South Asian female breast cancer survivors. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(2):e80–e89. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson HS, Littles M, Jacob S, Coker C. Posttreatment breast cancer surveillance and follow-up care experiences of breast cancer survivors of African descent: an exploratory qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(6):478–487. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan ME, Butow P, Spillane AJ, Boyle FM. Survivorship care after breast cancer: follow-up practices of Australian health professionals and attitudes to a survivorship care plan. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6(2):116–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hahn EE, Ganz PA, Melisko ME, et al. Provider perceptions and expectations of breast cancer posttreatment care: a University of California Athena Breast Health Network project. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):323–330. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parmeshwar R, Margenthaler JA, Allam E, Chen L, Virgo KS, Johnson FE. Patient surveillance after initial breast cancer therapy: variation by physician specialty. Am J Surg. 2013;206(2):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith SL, Wai ES, Alexander C, Singh-Carlson S. Caring for survivors of breast cancer: perspective of the primary care physician. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(5):e218–e226. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Hezewijk M, Hille ET, Scholten AN, Marijnen CA, Stiggelbout AM, van de Velde CJ. Professionals’ opinion on follow-up in breast cancer patients; perceived purpose and influence of patients’ risk factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Margenthaler JA, Allam E, Chen L, et al. Surveillance of patients with breast cancer after curative-intent primary treatment: current practice patterns. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(2):79–83. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donnelly P, Hiller L, Bathers S, Bowden S, Coleman R. Questioning specialists’ attitudes to breast cancer follow-up in primary care. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(9):1467–1476. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S459–S466. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwast AB, Drossaert CH, Siesling S, follow-up working group Breast cancer follow-up: from the perspective of health professionals and patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22(6):754–764. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beaver K, Luker KA. Follow-up in breast cancer clinics: reassuring for patients rather than detecting recurrence. Psychooncology. 2005;14(2):94–101. doi: 10.1002/pon.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grandjean I, Kwast AB, de Vries H, Klaase J, Schoevers WJ, Siesling S. Evaluation of the adherence to follow-up care guidelines for women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn EE, Hays RD, Kahn KL, Litwin MS, Ganz PA. Use of imaging and biomarker tests for posttreatment care of early-stage breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4316–4324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Factors related to underuse of surveillance mammogrraphy among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(1):85–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etim AE, Schellhase KG, Sparapani R, Nattinger AB. Effect of model of care delivery on mammography use among elderly breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96(3):293–299. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green-Haigh L. Mammographic surveillance in the follow-up of early primary breast cancer in England: a cross-sectional study. Radiography. 2009;15:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baena-Canada JM, Ramirez-Daffos P, Cortes-Carmona C, Rosado-Varela P, Nieto-Vera J, Benitez-Rodriguez E. Follow-up of long-term survivors of breast cancer in primary care versus specialist attention. Fam Pract. 2013;30(5):525–532. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Surveillance testing among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1074–1081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu W, Jansen L, Schaapveld M, Baas PC, Wiggers T, De Bock GH. Underuse of long-term routine hospital follow-up care in patients with a history of breast cancer? BMC Cancer. 2011;11:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onega T, Weiss J, Diflorio R, Mackenzie T, Goodrich M, Poplack S. Evaluating surveillance breast imaging and biopsy in older breast cancer survivors. Int J Breast Cancer. 2012;2012:347646. doi: 10.1155/2012/347646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field TS, Doubeni C, Fox MP, et al. Under-utilization of surveillance mammography among older breast cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(2):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schapira MM, McAuliffe TL, Nattinger AB. Underutilization of mammography in older breast cancer survivors. Med Care. 2000;38(3):281–289. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Worster A, Wood ML, McWhinney IR, Bass MJ. Who provides follow-up care for patients with early breast cancer? Can Fam Physician. 1995;41:1314–1320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Giudice ME, Moineddin R. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(4):174–181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geurts SM, de Vegt F, Siesling S, et al. Pattern of follow-up care and early relapse detection in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(3):859–868. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morris S, Corder AP, Taylor I. What are the benefits of routine breast cancer follow-up? Postgrad Med J. 1992;68(805):904–907. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.805.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nurgalieva ZZ, Franzini L, Morgan R, Vernon SW, Liu CC, Du XL. Surveillance mammography use after treatment of primary breast cancer and racial disparities in survival. Med Oncol. 2013;30(4):691. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lash TL, Fox MP, Buist DS, et al. Mammography surveillance and mortality in older breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3001–3006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snee M. Routine follow-up of breast cancer patients. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1994;6(3):154–156. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(94)80053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maly RC, Liu Y, Diamant AL, Thind A. The impact of primary care physicians on follow-up care of underserved breast cancer survivors. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(6):628–636. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.120345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization . Latest world cancer statistics. Global cancer burden rises to 14.1 million new cases in 2012: Marked increase in breast cancers must be addressed [press release] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Accessed August 7, 2014]. [December 12]. Available from: http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2013/pdfs/pr223_E.pdf. [Google Scholar]