Abstract

Defining the significant checkpoints in CFTR biogenesis should identify targets for therapeutic intervention with CFTR folding mutants like F508del. While the role of ubiquitylation and the ubiquitin proteasome system is well established in the degradation of this common CFTR mutant, the part played by SUMOylation is a novel aspect of CFTR biogenesis/quality control. We identified this post-translational modification of CFTR to result from its interaction with small heat shock proteins (Hsps), which were found to selectively facilitate the degradation of F508del through a physical interaction with the SUMO E2 enzyme, Ubc9. Hsp27 promoted the SUMOylation of mutant CFTR by the SUMO-2 paralog, which can form poly-chains. Poly-SUMO chains are then recognized by the SUMO targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL), RNF4, which elicited F508del degradation in a Hsp27-dependent manner. This work identifies a sequential connection between the SUMO and ubiquitin modifications of the CFTR mutant: Hsp27-mediated SUMO-2 modification, followed by ubiquitylation via RNF4 and degradation of the mutant via the proteasome. Other examples of the intricate cross talk between the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways are discussed in reference to other substrates; many of these are competitive and lead to different outcomes. It is reasonable to anticipate that further research on SUMO-ubiquitin pathway interactions will identify additional layers of complexity in the process of CFTR biogenesis and quality control.

Keywords: CFTR, degradation, SUMO, ubiquitin, proteasome, small heat shock proteins, Hsp27, SUMO- targeted degradation

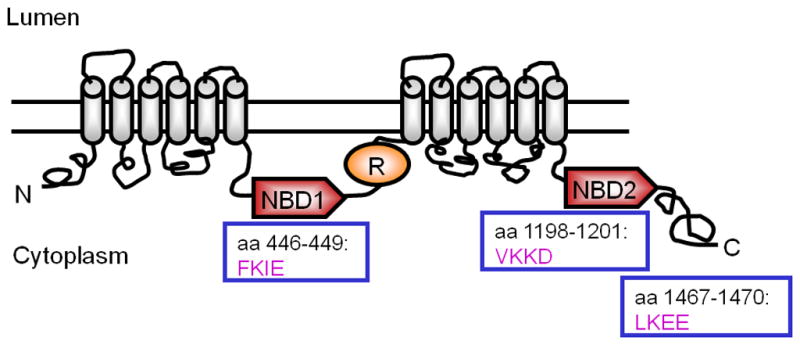

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a complex, polytopic protein comprised of 1480-amino acids that functions as cAMP regulated anion channel at the apical membranes of many epithelial cells, including those of the airways, pancreas, intestines, and other fluid-secreting epithelia [1]. Similar to other ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) family members, CFTR has a modular, multi-domain structure, consisting of two membrane spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2, each comprised of six transmembrane segments), two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), and a central R domain, the primary site of protein kinase-mediated channel regulation. Mutations in the CFTR gene lead to cystic fibrosis (CF), one of the most prevalent genetic disorders. The identification of ~2000 genetic mutations has led to their categorization into different molecular classes [2]. The most common disease mutation results in the deletion of a phenylalanine residue at position 508 [3], a class II mutation that is characterized by defective biogenesis and near-complete degradation at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [4]. CFTR’s complex folding pattern is reflected in the fact that more than half of the WT protein is also degraded in most cells, although, epithelial cells expressing endogenous CFTR process the WT channel more efficiently [5–9].

Ubiquitylation and ERAD

The translocation of newly synthesized membrane proteins into the ER represents the first step in their transit along the secretory pathway. At this early stage, they begin to encounter a series of quality control (QC) events that monitor proper protein folding and domain assembly [10]. Success in ER folding/assembly is a prerequisite for protein exit from the ER, and a significant fraction of translated proteins is believed to fail the serial QC checkpoints that they encounter [11]. In general, the retention of proteins at these ER checkpoints leads to their ubiquitylation and degradation by the 26S proteasome, a process denoted as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [12, 13]. Two recent papers report that in mammalian cells and yeast, 15 % and 5 %, respectively, of total proteins are ubiquitylated during their translation. Although these statements reflect % total protein, not all proteins are equally represented in this pool, the majority being long and difficult to fold proteins like CFTR [14, 15].

Ubiquitylation occurs via a multi-step enzymatic reaction in which the polypeptide ubiquitin is covalently attached to the ε-amino group of a lysine side chain of a substrate. In an ATP-dependent step, a catalytic cysteine in the single ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1) forms a thioester bond with the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin. The activated polypeptide is then transferred to one of dozens of ubiquitin conjugating enzymes (E2), again via the formation of a thioester bond at a catalytic cysteine. Subsequently, one of hundreds of ubiquitin E3 ligases catalyzes the covalent modification of a selected substrate with the activated ubiquitin via an isopeptide bond [16]. Poly-ubiquitylation may then ensue when additional ubiquitin peptides are linked to form a chain. In contrast to ERAD, mono-ubiquitylation and multimono-ubiquitylation may regulate subcellular substrate localization as well as enzymatic activity. While non-canonical chain length and site of linkage may vary (e.g. residues other than internal lysine, chains linked to other than lysine 48 in ubiquitin, and mixed chains of ubiquitin and a ubiquitin-like modifier), the formation of a ubiquitin poly-chain is a prerequisite for degradation by the 26S proteasome [17, 18]. However, alternative forms of the proteasome are able to degrade non-ubiquitylated substrates [19]. Covalent modification of target proteins with ubiquitin is reversible. Deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs) are able to reverse substrate ubiquitylation and forestall degradation, thus protecting them from proteolysis by the 26S proteasome. The approximately 100 DUBs found in mammals are categorized into 5 families: ubiquitin-C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ubiquitin specific proteases (USPs), ovarian-tumor (OTU) domain DUBs, Machado-Josef domain (MJD) DUBs, and Jab1/MPN metalloenzyme (JAMM) domain DUBs. (reviewed in [20]).

ERQC assures that only competent proteins arrive at their appropriate cellular destinations, thus avoiding cell stress and the formation of toxic protein aggregates arising from accumulation of aberrant proteins within the ER. The bipolar properties of molecular chaperones allow these proteins to either facilitate substrate folding or degradation, depending on the conformational state of the target protein [10, 21].

CFTR folding is facilitated by an ER-based core chaperone machinery that includes Hsp70 [22–24], Hsp90 [25, 26], the Hsp40 co-chaperones [27–31], and calnexin [32–34]. A reduction in NBD1 aggregation is observed upon interaction with Hsp70 and CFTR folding efficiency improves [35]. However, unstable conformations of the ion channel remain bound to chaperones, and extended interactions with Hsp70/Hsp90 results in CFTR ubiquitylation through the combined action of the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme UbcH5a, Csp and the ubiquitin ligase, CHIP, and, thus, degradation by the 26S proteasome [5, 36–39]. Recent data indicates that a complex involving Derlin-1 and the ubiquitin ligase, RMA1, monitor early steps in CFTR conformational maturation. Together with p97 and the E2 Ubc6e, these components lead to ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of the ion channel [37, 39]. In addition, gp78 has been implicated in ubiquitin chain elongation, functioning downstream of RMA1 [40]. Furthermore, small heat shock proteins (sHsps) have been shown to preferentially increase ubiquitylation and degradation of F508del CFTR, as discussed in more detail below [41]. Interestingly, the ER-resident ubiquitin specific protease 19 (Usp19), a DUB, has been reported to play a role in the unfolded protein response and is able to rescue F508del CFTR, among other ERAD substrates [42].

SUMOylation

Although much literature associates modification by SUMO with nuclear regulatory events, it is clear also that the components of this pathway regulate a wide array of extranuclear functions [43]. In addition to its well characterized role in transcriptional regulation, SUMO modification can adjust protein expression levels via protein degradation [41, 44] in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments.

The SUMO conjugation cascade resembles that for ubiquitin. SUMO is initially activated by the introduction of a thioester bond between its C-terminal diglycine and the catalytic cysteine of the E1 activating enzyme, SAE1/SAE2, and this requires ATP hydrolysis. SUMO is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine of the single known E2 enzyme in this pathway, Ubc9, which can then directly transfers SUMO to the ε-amino group of a lysine on its substrate, resulting in covalent, isopeptide bond formation. Most but not all acceptor sites recognized by Ubc9 contain a consensus SUMOylation motif, ψKxE/D, where ψ is a bulky hydrophobic residue. CFTR contains three consensus SUMOylation motifs, one in NBD1, one in NBD2, and one at the C-terminus (Fig. 1). Unlike the ubiquitin cascade, the SUMO E2, Ubc9, can perform the substrate transfer function without E3 assistance; rather, SUMO E3s generally assist with substrate selection and catalytically enhance transfer of the modifier [45]. There are four SUMO paralogs in mammals, three of which (SUMO-1,-2, and -3) contain the C-terminal diglycine motif required for covalent attachment. While SUMO-1 has only 50% homology to the SUMO-2 and -3 paralogs, the latter differ by only 4 amino acids, and they cannot be distinguished immunologically. SUMO-2 and -3 contain a consensus SUMOylation motif, which allows them to form poly-chains [46]. As with ubiquitin, SUMO conjugates are cleaved by specific cysteine proteases, and in mammalian cells, six SENP protease orthologs are expressed: sentrin-specific proteases, SENP1-3, SENP 5-7. Additional SUMO proteases include USPL1 (ubiquitin-specific protease-like 1), and DES1 and 2 (desumoylating isopeptidase 1 and 2), but their targets are as yet poorly identified. A dynamic interplay between conjugating enzymes and proteases can make the steady-state detection of sumoylated proteins difficult experimentally, and this is widely acknowledged [45, 47]. Many target proteins are briefly sumoylated, in a temporal or spatially regulated manner, and in the steady-state, most are modified at low levels.

Fig. 1.

CFTR has three SUMO consensus sites. This simplistic model showing the domain structure of CFTR indicates the locations of three predicted SUMOylation sites within the protein, one each located in NBD1, NBD2, and at the C-terminus. Whether these are the sites used in Hsp27-dependent SUMOylation requires further evaluation.

A recent study found F508del CFTR, and to a lesser extent, the WT CFTR channel to be SUMOylated [41]. Although modification with SUMO-1 as well as with SUMO-2/3 was detected, the sHsp Hsp27 preferentially facilitated the attachment of SUMO-2 to the mutant protein. The ability of Hsp27 to differentiate between WT and F508del CFTR, physically and functionally, and to promote SUMO-2 modification has been demonstrated in vivo for the full length protein as well as in vitro using F508del NBD1 and purified pathway components. Ultimately, sHsp facilitated SUMOylation leads to mutant CFTR ubiquitylation and degradation (see discussion below). The modification of CFTR with SUMO was reversible by over-expression of SENP1 in vivo or its addition in vitro [41].

sHsps have been shown to interact with proteins of an intermediate, foldable conformation rather than with either native structures or completely denatured proteins [48–50]. Moreover, they can distinguish between structurally identical WT and mutant proteins based on small differences in their free energies of unfolding [51–54]. A similar discrimination capacity applies to sHsp interactions with WT vs. F508del CFTR. Comparisions of the crystal structures of WT and F508del CFTR reveal only minimal differences in protein conformation and changes to the surface topography only in the vicinity of the deletion [55]. Comparison of the proteolytic cleavage patterns of WT and F508del CFTR reveals their conformational differences.

Mature, WT CFTR is distinguished by protease resistance suggesting a compact, folded state, whereas the digestion patterns of the immature WT and F508del proteins are more prone to proteolysis, implying more open conformations [56, 57]. Thus, ER-retained F508del CFTR appears to achieve an intermediate conformation along the normal folding pathway, but its maturation is arrested at one or more critical QC checkpoints.

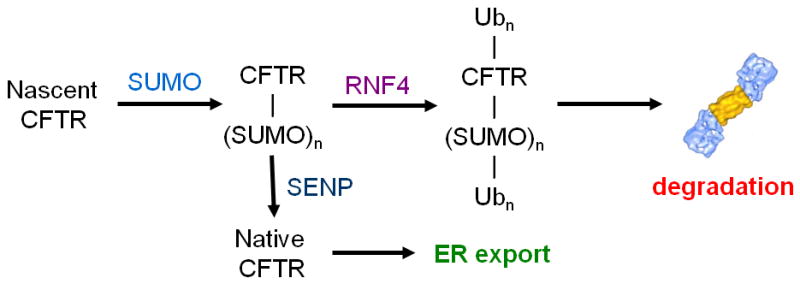

Furthermore, the utility of SUMO-protein fusions to enhance protein production in prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems exploits the ability of SUMO to maintain protein solubility [58]. This raises the possibility of a dual function of the peptide modifier (see Fig. 2). SUMO modification might stabilize CFTR during its folding and domain assembly processes, but the adduct would be removed by a SUMO protease as folding/assembly is completed and the native conformation obtained. However, if SUMO can’t be cleaved, possibly because CFTR’s folding state denies access to a SUMO protease, then modified, misfolded CFTR is targeted for degradation. Alternatively, these distinct positive and negative functions might be facilitated by different SUMO paralogs. For example, SUMO-1 may play a pro-folding role in CFTR biogenesis, while SUMO-2 modified F508del CFTR is directed to proteolysis. While speculative, the latter possibility is particularly interesting in light of the fact that the ion channel is modified with either SUMO paralog, but Hsp27, via its interaction with Ubc9, facilitates CFTR conjugation by SUMO-2 poly-chains and preferentially interacts with the mutant protein.

Fig. 2.

Putative bipolar effects of SUMOylation on CFTR. This simplified reaction scheme portrays the two opposing outcomes of CFTR SUMOylation. First, nascent CFTR is covalently modified by SUMO, mediated by Hsp27’s interaction with CFTR and the SUMO E2, Ubc9. This modification is proposed to enhance the solubility of CFTR folding intermediates during folding and domain assembly. If successful, these processes will expose the isopeptide bond(s) between CFTR and the modifier, allowing SUMO specific proteases (SENPs) to reverse the modification and yielding native, folded CFTR, ready for export to the plasma membrane. Alternatively, if SUMO remains bound to F508del CFTR, or to some fraction of misfolded WT protein, the STUbL, RNF4, recognizes the poly-SUMOylated ion channel and initiates poly-ubiquitylation, either on different lysine residues or as modifications of the SUMO poly-chain, leading to CFTR degradation by the 26S proteasome.

Cross talk between the ubiquitin and SUMO pathways

While ubiquitylation and SUMOylation represent discrete modifications that can lead to different outcomes, cross talk between these pathways has been identified. There are a number of proteins that can be conjugated to either modifier, usually with different outcomes.

This interaction may have a competitive basis, in which SUMO and ubiquitin contend for attachment at the same Lysine residue and result in the conferral of opposite or different fates on the substrate. For example, IκBα (inhibitor of NF-κB) is degraded upon its phosphorylation-induced ubiquitylation on Lys21 and Lys22, while SUMOylation on Lys21 stabilizes the protein. Similarly, SUMOylation on Lys277 and Lys309 translocates NEMO (IκB kinase regulatory particle) to the nucleus while phosphorylation-induced ubiquitylation of the same residues translocates NEMO back to the cytoplasm. The functional regulation of the homotrimeric Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) is even more complex. PCNA coordinates DNA damage repair as well as post-replication repair. When it is mono-ubiquitylated at Lys164, PCNA facilitates translesion synthesis, a DNA repair pathway that is prone to error; however, construction of a poly-ubiquitin chain at this site promotes an error-free repair process by PCNA. Conversely, SUMOylation at Lys164 during S-phase prevents PCNA-induced DNA recombination [59, 60].

While we don’t as yet have evidence for either competitive or differential ubiquitin-SUMO interplay in CFTR regulation, there is evidence supporting sequential SUMO/ubiquitin modifications [41]. That is, Hsp27 induced SUMO-2 modification facilitated ubiquitylation of F508del CFTR by RNF4 (see below), SUMO-1 modification of CFTR was also detected, which might support CFTR folding. Furthermore, the possibility that SUMO modification may stabilize WT CFTR at the plasma membrane by reducing its internalization, promoting recycling or modifying its channel activity, as reported for other ion channels, has yet to be addressed [43]. Which of the many lysine residues in CFTR are modified with SUMO-1, SUMO-2/3 and ubiquitin, and whether sites of modification overlap has yet to be determined. NBD1 is SUMOylated in vitro suggesting that at least one target lysine resides within this domain, and additional sites are likely localized elsewhere in the protein (Fig. 1).

In contrast to the competitive nature of the SUMO/ubiquitin interplay described above for other proteins, these post-translational modifications can as well cooperate to produce a similar outcome. In a sequential manner, SUMO modification can serve as a targeting signal for the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. The concept of a mechanism for proteolytic regulation of proteins modified by poly-SUMO signals has emerged from the finding that SUMO-2/3 poly-chain conjugates accumulate when mammalian cells were exposed to proteasome inhibitors [61]. This finding led to the identification of a new class of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) in yeast, and subsequently, the human orthologue, RNF4, was shown to target proteins modified with poly-SUMO chains for degradation via ubiquitin-dependent pathways [62]. STUbLs recognize poly-SUMOylated targets via their tandem SUMO interacting motif(s), an interaction that leads to substrate ubiquitylation and degradation via the 26S proteasome [44, 62]. RNF4 optimally recognizes poly-SUMO chains containing four SUMO residues [62]. Prior studies of the SUMO-targeted ubiquitin E3s, RNF4 and VHL have focused on the role of these modulators in the regulation of nuclear transcriptional activity or the translocation of proteins between cytoplasm and nucleus [63].

This resolved site of action was expanded recently by the identification of a cytoplasmic substrate for RNF4, F508del CFTR. As reported above, the mutant ion channel is modified with SUMO-2 via the combined action of Hsp27 and Ubc9, ultimately leading to its proteolysis [41]. Poly-SUMOylated F508del CFTR is recognized by RNF4, presumably via its N-terminal, tandem SUMO interacting motifs, which then mediates ubiquitylation via its C-terminal RING domain, with subsequent degradation of the mutant by the 26S proteasome. RNF4 over-expression and knock down mimicked the action of over-expression and knock down of Hsp27, as well as actions of enzymes of the SUMOylation pathway. Moreover, the interdependence of the sHsp/SUMO pathway and RNF4 was demonstrated by the loss of function of Hsp27’s impact on F508del degradation in response to the expression of a dominant negative RNF4, and conversely, loss of the ability of RNF4 to degrade F508del CFTR following the knock down of Hsp27, presumably due to loss of SUMOylation of the mutant protein. Whether the Hsp27/SUMO/RNF4 QC pathway contributes also to the ~60% degradation of WT CFTR occurring in heterologous expression systems will require further study.

The connections between the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways become even more intricate when considering the fact that the enzymes of one pathway can be regulated by the other. For example, the stability of two SUMO-specific proteases, Senp2 and 3, are regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system [47, 59, 60]. Moreover, the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, E2-25k, is inactivated by its SUMOylation. The ubiquitin E3 ligase Mdm2 can self-ubiquitylate leading to its degradation, which can be prevented by SUMOylation at the same lysine residue. The ubiquitin E3 BRCA1 requires SUMOylation in order to be able to modify its substrates with ubiquitin chains. In the case of the ubiquitin-specific protease USP25, SUMO and ubiquitin compete for the same Lysine residue with SUMO silencing and mono-ubiquitin activating this enzyme [59, 60]. SUMOylation of the STUbL, VHL, is responsible for its nuclear localization and increased stability while ubiquitylation targets this E3 ligase to the cytoplasm [64]. While no such reciprocal regulation of CFTR modulators has yet been identified, it is not only possible but highly likely that such interactions occur.

Timing

As noted above, model protein studies show that sHsps elude interactions with either native structures or completely denatured proteins, yet they associate with proteins having an intermediate, foldable conformation [48–50]. Furthermore, sHsp chaperones function in an ATP-independent manner, maintaining their client proteins in a soluble state, and providing the potential for ATP-dependent, core chaperones, e.g. Hsp70 and Hsp90, components that are recognized facilitators of CFTR folding, to refold sHsp target proteins [65–70]. This concept implies that the sHsp-SUMO-STUbL pathway may lie upstream of CFTR recognition by quality control checkpoints in which misfolded CFTR is ubiquitylated by the Derlin-RMA1 and CHIP E3 ligase complexes [37, 39, 71] in mediating CFTR quality control. Yet, two very recent reports provide evidence of co-translational ubiquitylation of mainly long proteins with a low propensity to fold [14, 15]. While this might be the earliest quality control checkpoint for proteins, and CFTR would likely be a good candidate, the subset of ubiquitin E3s involved in this process proved to be very limited in yeast. Although the yeast STUbLs were not among the E3s identified to modify substrates co-translationally, it will be interesting to investigate a SUMO dependence of this process at least in mammalian cells. Furthermore, E3s involved in CFTR degradation should be tested for their potential to act during protein biosythesis. This will shed light on the question of whether co-translational ubiquitylation is a separate mechanism, mediated by its own set of enzymes, or if known facilitators of CFTR degradation intervene at this early stage. Additional studies will be required to determine whether SUMO modification is an early event that facilitates CFTR folding and domain assembly, and should these processes fail, then target the protein for disposal, as suggested by the model of Fig. 2.

Concluding remarks

While the role of ubiquitylation is well established in the ERAD of F508del CFTR, the part played by SUMOylation is a novel aspect of CFTR biogenesis/quality control. Best established at present is the connection between the two pathways: Hsp27-mediated SUMO-2 modification of F508del CFTR leading to ubiquitylation by RNF4 and degradation of the mutant via the proteasome. As suggested by the intricate cross talk between these pathways uncovered for other substrates, it is to be expected that further research will add layers of complexity to these aspects of F508del CFTR quality control. There remain many open questions, for example, how do these pathways determine the fates of WT CFTR and other folding mutants? Is there physiological modification of CFTR by SUMO-1, and if so, what is its purpose? Which lysine residues are ubiquitylated, which are SUMOylated, and is there overlap, which would imply competition? Different modification sites and different isoforms might lead to diverse outcomes. Is the quality control/biogenesis of other cytoplasmic and integral membrane proteins regulated in a similar manner? The answers to these questions will expose the intricacy and intimacy of these post-translational modifications.

Acknowledgments

The authors and their research are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK68196 and DK72506) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (FRIZZE05XX0).

Abbreviations

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- SUMO

small ubiquitin like modifier

- STUbL

SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase

- sHsp

small heat shock protein

- MSD

membrane spanning domain

- NBD

nucleotide binding domain

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation

- QC

quality control

- DUB

deubiquitylating enzyme

References

- 1.Pilewski JM, Frizzell RA. Role of CFTR in airway disease. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S215–55. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerem E, Kerem B. The relationship between genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1995;1:450–6. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O’Riordan CR, Smith AE. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1990;63:827–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen TJ, Loo MA, Pind S, Williams DB, Goldberg AL, Riordan JR. Multiple proteolytic systems, including the proteasome, contribute to CFTR processing. Cell. 1995;83:129–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreda SM, Mall M, Mengos A, Rochelle L, Yankaskas J, Riordan JR, Boucher RC. Characterization of wild-type and {delta}f508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human respiratory epithelia. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2154–67. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lukacs GL, Mohamed A, Kartner N, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. Conformational maturation of CFTR but not its mutant counterpart (delta F508) occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and requires ATP. Embo J. 1994;13:6076–86. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga K, Jurkuvenaite A, Wakefield J, Hong JS, Guimbellot JS, Venglarik CJ, Niraj A, Mazur M, Sorscher EJ, Collawn JF, Bebok Z. Efficient intracellular processing of the endogenous cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in epithelial cell lines. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:22578–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward CL, Kopito RR. Intracellular turnover of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Inefficient processing and rapid degradation of wild-type and mutant proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:25710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–91. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schubert U, Anton LC, Gibbs J, Norbury CC, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature. 2000;404:770–4. doi: 10.1038/35008096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kostova Z, Wolf DH. For whom the bell tolls: protein quality control of the endoplasmic reticulum and the ubiquitin-proteasome connection. Embo J. 2003;22:2309–17. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCracken AA, Brodsky JL. Evolving questions and paradigm shifts in endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) Bioessays. 2003;25:868–77. doi: 10.1002/bies.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duttler S, Pechmann S, Frydman J. Principles of cotranslational ubiquitination and quality control at the ribosome. Molecular cell. 50:379–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, Durfee LA, Huibregtse JM. A cotranslational ubiquitination pathway for quality control of misfolded proteins. Molecular cell. 50:368–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:7151–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kravtsova-Ivantsiv Y, Ciechanover A. Non-canonical ubiquitin-based signals for proteasomal degradation. Journal of cell science. 125:539–48. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J, Gordon C. The regulation of proteasome degradation by multi-ubiquitin chain binding proteins. FEBS letters. 2005;579:3224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jariel-Encontre I, Bossis G, Piechaczyk M. Ubiquitin-independent degradation of proteins by the proteasome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1786:153–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson KD. DUBs at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:2325–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fewell SW, Travers KJ, Weissman JS, Brodsky JL. The action of molecular chaperones in the early secretory pathway. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:149–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choo-Kang LR, Zeitlin PL. Induction of HSP70 promotes DeltaF508 CFTR trafficking. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L58–68. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubenstein RC, Zeitlin PL. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate downregulates Hsc70: implications for intracellular trafficking of DeltaF508-CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C259–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Janich S, Cohn JA, Wilson JM. The common variant of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is recognized by hsp70 and degraded in a pre-Golgi nonlysosomal compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9480–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loo MA, Jensen TJ, Cui L, Hou Y, Chang XB, Riordan JR. Perturbation of Hsp90 interaction with nascent CFTR prevents its maturation and accelerates its degradation by the proteasome. Embo J. 1998;17:6879–87. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Youker RT, Walsh P, Beilharz T, Lithgow T, Brodsky JL. Distinct roles for the Hsp40 and Hsp90 molecular chaperones during cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator degradation in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4787–97. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alberti S, Bohse K, Arndt V, Schmitz A, Hohfeld J. The cochaperone HspBP1 inhibits the CHIP ubiquitin ligase and stimulates the maturation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4003–10. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farinha CM, Nogueira P, Mendes F, Penque D, Amaral MD. The human DnaJ homologue (Hdj)-1/heat-shock protein (Hsp) 40 co-chaperone is required for the in vivo stabilization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by Hsp70. Biochem J. 2002;366:797–806. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meacham GC, Lu Z, King S, Sorscher E, Tousson A, Cyr DM. The Hdj-2/Hsc70 chaperone pair facilitates early steps in CFTR biogenesis. Embo J. 1999;18:1492–505. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Peters KW, Sun F, Marino CR, Lang J, Burgoyne RD, Frizzell RA. Cysteine string protein interacts with and modulates the maturation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:28948–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Schmidt BZ, Sun F, Condliffe SB, Butterworth MB, Youker RT, Brodsky JL, Aridor M, Frizzell RA. Cysteine string protein monitors late steps in CFTR biogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farinha CM, Amaral MD. Most F508del-CFTR is targeted to degradation at an early folding checkpoint and independently of calnexin. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5242–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5242-5252.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okiyoneda T, Harada K, Takeya M, Yamahira K, Wada I, Shuto T, Suico MA, Hashimoto Y, Kai H. Delta F508 CFTR pool in the endoplasmic reticulum is increased by calnexin overexpression. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:563–74. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pind S, Riordan JR, Williams DB. Participation of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone calnexin (p88, IP90) in the biogenesis of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:12784–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strickland E, Qu BH, Millen L, Thomas PJ. The molecular chaperone Hsc70 assists the in vitro folding of the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:25421–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meacham GC, Patterson C, Zhang W, Younger JM, Cyr DM. The Hsc70 co-chaperone CHIP targets immature CFTR for proteasomal degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:100–5. doi: 10.1038/35050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun F, Zhang R, Gong X, Geng X, Drain PF, Frizzell RA. Derlin-1 promotes the efficient degradation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and CFTR folding mutants. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:36856–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell. 1995;83:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younger JM, Chen L, Ren HY, Rosser MF, Turnbull EL, Fan CY, Patterson C, Cyr DM. Sequential quality-control checkpoints triage misfolded cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Cell. 2006;126:571–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morito D, Hirao K, Oda Y, Hosokawa N, Tokunaga F, Cyr DM, Tanaka K, Iwai K, Nagata K. Gp78 cooperates with RMA1 in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of CFTRDeltaF508. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1328–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahner A, Gong X, Schmidt BZ, Peters KW, Rabeh WM, Thibodeau PH, Lukacs GL, Frizzell RA. Small heat shock proteins target mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator for degradation via a small ubiquitin-like modifier-dependent pathway. Molecular biology of the cell. 24:74–84. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassink GC, Zhao B, Sompallae R, Altun M, Gastaldello S, Zinin NV, Masucci MG, Lindsten K. The ER-resident ubiquitin-specific protease 19 participates in the UPR and rescues ERAD substrates. EMBO reports. 2009;10:755–61. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin S, Wilkinson KA, Nishimune A, Henley JM. Emerging extranuclear roles of protein SUMOylation in neuronal function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:948–59. doi: 10.1038/nrn2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geoffroy MC, Hay RT. An additional role for SUMO in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Nature reviews. 2009;10:564–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hay RT. SUMO: a history of modification. Mol Cell. 2005;18:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:35368–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hickey CM, Wilson NR, Hochstrasser M. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nature reviews. 13:755–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindner RA, Treweek TM, Carver JA. The molecular chaperone alpha-crystallin is in kinetic competition with aggregation to stabilize a monomeric molten-globule form of alpha-lactalbumin. Biochem J. 2001;354:79–87. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajaraman K, Raman B, Rao CM. Molten-globule state of carbonic anhydrase binds to the chaperone-like alpha-crystallin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:27595–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Treweek TM, Lindner RA, Mariani M, Carver JA. The small heat-shock chaperone protein, alpha-crystallin, does not recognize stable molten globule states of cytosolic proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1481:175–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koteiche HA, McHaourab HS. Mechanism of chaperone function in small heat-shock proteins. Phosphorylation-induced activation of two-mode binding in alphaB-crystallin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:10361–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McHaourab HS, Dodson EK, Koteiche HA. Mechanism of chaperone function in small heat shock proteins. Two-mode binding of the excited states of T4 lysozyme mutants by alphaA-crystallin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:40557–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sathish HA, Koteiche HA, McHaourab HS. Binding of destabilized betaB2-crystallin mutants to alpha-crystallin: the role of a folding intermediate. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:16425–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shashidharamurthy R, Koteiche HA, Dong J, McHaourab HS. Mechanism of chaperone function in small heat shock proteins: dissociation of the HSP27 oligomer is required for recognition and binding of destabilized T4 lysozyme. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:5281–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis HA, Zhao X, Wang C, Sauder JM, Rooney I, Noland BW, Lorimer D, Kearins MC, Conners K, Condon B, Maloney PC, Guggino WB, Hunt JF, Emtage S. Impact of the deltaF508 mutation in first nucleotide-binding domain of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator on domain folding and structure. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:1346–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Du K, Sharma M, Lukacs GL. The DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:17–25. doi: 10.1038/nsmb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang F, Kartner N, Lukacs GL. Limited proteolysis as a probe for arrested conformational maturation of delta F508 CFTR. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:180–3. doi: 10.1038/nsb0398-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Denuc A, Marfany G. SUMO and ubiquitin paths converge. Biochemical Society transactions. 38:34–9. doi: 10.1042/BST0380034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Praefcke GJ, Hofmann K, Dohmen RJ. SUMO playing tag with ubiquitin. Trends in biochemical sciences. 37:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uzunova K, Gottsche K, Miteva M, Weisshaar SR, Glanemann C, Schnellhardt M, Niessen M, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Johnson ES, Praefcke GJ, Dohmen RJ. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic control of SUMO conjugates. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:34167–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT. RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:538–46. doi: 10.1038/ncb1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perry JJ, Tainer JA, Boddy MN. A SIM-ultaneous role for SUMO and ubiquitin. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cai Q, Robertson ES. Ubiquitin/SUMO modification regulates VHL protein stability and nucleocytoplasmic localization. PloS one. 5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Cashikar AG, Duennwald M, Lindquist SL. A chaperone pathway in protein disaggregation. Hsp26 alters the nature of protein aggregates to facilitate reactivation by Hsp104. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:23869–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502854200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ehrnsperger M, Graber S, Gaestel M, Buchner J. Binding of non-native protein to Hsp25 during heat shock creates a reservoir of folding intermediates for reactivation. Embo J. 1997;16:221–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedrich KL, Giese KC, Buan NR, Vierling E. Interactions between small heat shock protein subunits and substrate in small heat shock protein-substrate complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:1080–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haslbeck M, Miess A, Stromer T, Walter S, Buchner J. Disassembling protein aggregates in the yeast cytosol. The cooperation of Hsp26 with Ssa1 and Hsp104. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:23861–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee GJ, Roseman AM, Saibil HR, Vierling E. A small heat shock protein stably binds heat-denatured model substrates and can maintain a substrate in a folding-competent state. Embo J. 1997;16:659–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Torok Z, Goloubinoff P, Horvath I, Tsvetkova NM, Glatz A, Balogh G, Varvasovszki V, Los DA, Vierling E, Crowe JH, Vigh L. Synechocystis HSP17 is an amphitropic protein that stabilizes heat-stressed membranes and binds denatured proteins for subsequent chaperone-mediated refolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3098–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051619498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmidt BZ, Watts RJ, Aridor M, Frizzell RA. Cysteine string protein promotes proteasomal degradation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by increasing its interaction with the C terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein and promoting CFTR ubiquitylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:4168–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806485200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]