Abstract

We determined the prevalence of erythromycin-resistant bacteria in the oral cavity and identified mef and erm(B) as the most common resistance determinants. In addition, we demonstrate the genetic linkage, on various Tn1545-like conjugative transposons, between erythromycin and tetracycline resistance in a number of isolates.

The macrolide erythromycin or its derivatives are commonly used in poultry, livestock, and human clinical practice to prevent infections due to gram-positive bacteria. In humans, macrolides are used for the treatment of respiratory tract infections or as an alternative to penicillin in patients who are allergic to that antibiotic (23). During the last two decades there have been increases in the levels of resistance to erythromycin among clinical as well as commensal isolates, and these increases correlate with the increased use of this class of antibiotics (9, 11, 19, 25, 32, 33). The oral cavity is one of the most densely colonized environments in humans. It has already been shown that the cultivable oral bacteria are an important reservoir for different tetracycline resistance genes (31). The interchange of resistance genes between different species in the oral cavity as well as between oral bacteria and bacteria from other environments has been described previously (14, 20, 21). The aim of this study was to examine the resistance to macrolides among oral bacteria from 20 healthy adults without prior or concomitant exposure to macrolides, as well as its possible linkage with tetracycline resistance.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The saliva and dental plaque samples were obtained and processed separately for each individual, as noted by Villedieu et al. (31). The MICs of erythromycin and tetracycline for each isolate were determined according to the recommendations of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (15). The different macrolide resistance phenotypes were identified by using disks containing erythromycin (30 μg) or clindamycin (10 μg), as described by Seppäla et al. (26). Each isolate was also tested for its susceptibility to azithromycin (100 μg) and spiramycin (100 μg) by the use of disks (Oxoid) on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid) with 5% defibrinated horse blood (E & O Laboratories, Bonnybridge, Scotland). All of the gram-negative isolates were tested for their susceptibilities to crystal violet and Triton X-100 (Sigma) by the agar plating method described by Shafer et al. (28).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics or source | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Bacillus subtilis BS34A | B. subtilis CU2189::Tn916 | 22 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes AC1 | erm(B), plasmid pAC1 | 29 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes 02C1064 | mef(A) | 29 |

| Staphylococcus aureus RN1389 | erm(A), Tn554 in the chromosome | 29 |

| Staphylococcus aureus RN4220 | erm(C), plasmid pE194 | 29 |

| Staphylococcus aureus RN4220 | msr(A), plasmid pAT10 | 29 |

| Escherichia coli BM694(pAT63) | ere(A), pBR322 plasmid with cloned insert | 29 |

| Escherichia coli BM694(pAT72) | ere(B), pUC8 plasmid with cloned insert | 29 |

| Escherichia coli L441D | mph(A) | 29 |

| Escherichia coli V831 | erm(F), pVA831 (pBF4) in pBR325 vector | 3 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAM120 | pGL101 carrying EcoR1 F′ (F::Tn916) of pAD1 | 8 |

| pPPM70 | pUC18 containing IntronΔkan | 21 |

| pGEM-tetW | pGEM carrying a 2.4-kb PCR product with the tet(W) gene from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | 1 |

| pGEM-tetO | pGEM carrying the tet(O) gene from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | 1 |

| pAT451 | pUC18 carrying a 4.5-kb ClaI fragment of pIP811 with the tet(S) gene | 1 |

| pAT102 | tet(K) | 17 |

Resistant isolates were characterized to the genus level by biochemical tests and partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, as described previously (31). The resistant isolates were tested for the presence of erythromycin resistance genes by either an individual PCR assay, as described for mph(A) (29), or a multiplex PCR. Group I multiplex PCRs included erm(B) and erm(C); and group II multiplex PCRs included erm(A), erm(F), and msr(A), with the same conditions specified by Nawaz et al. (16) being used for both PCRs. The primers whose sequences were specific for erm(F) were obtained from Chung et al. (3). The group III multiplex PCR consisted of ere(A), ere(B), and mef(A), as stated by Sutcliffe et al. (29). Isolates that were resistant to both erythromycin and tetracycline were also tested for the presence of tetracycline resistance genes (31), and the strains were tested for their abilities to simultaneously transfer both genes to Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2, which is resistant to rifampin (20). Total DNA from the parents and transconjugants was digested with HindIII (Promega), run into an agarose gel, and transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech UK Ltd., Little Chalfont, England) by Southern blotting. Hybridizations were performed with probes specific for tet(M), erm(B), plasmid pAM120 (containing Tn916), plasmid pPPM70 (containing aphA-3), or int/xis (the integrase specific for the Tn916-Tn1545 family of transposons) by using the Alkphos Direct hybridization kit (Amersham), according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

On average, 7% of the cultivable microbiota from the 20 samples were found to be erythromycin resistant and to carry at least one erythromycin resistance gene. Most of the erythromycin-resistant isolates with an identified resistance gene were streptococci, and the most common resistance gene was mef, followed by erm(B). These results agree with those of previous studies that showed that viridans group streptococci from pharyngeal samples are reservoirs for erm(B) and mef genes (2, 12). The mef gene was detected in 67% of the isolates with an identified erythromycin resistance gene; most of the isolates were characterized as Streptococcus spp., and two were characterized as Neisseria spp. Some mef genes have recently been found to be contained within a novel conjugative transposon, Tn1207.3 (24). Additionally the msr(A) efflux gene was identified in one Staphylococcus sp. The methylase gene was found in 33% of the isolates with an identified erythromycin resistance gene; most of these isolates (31%) were streptococci and carried an erm(B) gene; however, one erm(B) gene was isolated from a Veillonella sp. for the first time. One isolate carried both the erm(B) and the mef genes, and erm(F) was isolated from a Prevotella sp.

Only 6.5% of the gram-negative isolates had an identified erythromycin resistance gene. A further 26.5% were resistant to elevated concentrations of both crystal violet and Triton X-100 (data not shown); therefore, according to the criteria of Morse et al. (14), they are likely to have the mtr (multiple transformable resistances) phenotype. The presence of an mtr efflux pump reduces the permeability of the outer membrane of the isolate to dyes and detergents and increases the levels of resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, such as macrolides (28). The remaining gram-negative isolates that had no identified erythromycin resistance genes and that did not present an mtr phenotype are likely to be intrinsically resistant to macrolides (7).

As noted in previous studies (2, 4, 6, 9, 10, 13, 32), there was a correlation between the antibiotic resistance phenotype and the genotype for each isolate. The isolates with a methylase gene were fully resistant to the macrolides (erythromycin, arithromycin, spiramycin) and to a lincosamide (clindamycin), whereas the isolates with a mef gene displayed various zones of inhibition around the antibiotic disks (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of the methylase and efflux genes in oral bacteria

| Erythromycin resistance gene | No. of isolates | Genus | ERY MIC (μg/ml)a | Erythromycin resistance gene(s) | Resistance to ERY, CLI, AZM, and SPY disksb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylase genes | 11 | Streptococcus | 64 | erm(B) | Fully resistant |

| 1 | Streptococcus | >128 | mef + erm(B) | Fully resistant | |

| 1 | Veillonella | 32 | erm(B) | Fully resistant | |

| 1 | Prevotella | 4 | erm(F) | Fully resistant | |

| Efflux pump | 21 | Streptococcus | 4 | mef | Variable zones of inhibition |

| 1 | Streptococcus | >128 | mef + erm(B) | Fully resistant | |

| 3 | Neisseria | 4-8 | mef | Variable zones of inhibition | |

| 2 | Lactobacillus | 2-8 | mef | Variable zones of inhibition | |

| 1 | Staphylococcus | >128 | msrA | Variable zones of inhibition |

The MIC breakpoint of erythromycin for Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus, and Neisseria spp. is <0.5 μg/ml and that for anaerobes is <2 μg/ml, according to the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (http://www.bsac.org.uk/). The MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates are inhibited for all isolates with a methylase gene were 64 and 128 μg/ml, respectively; and the MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates are inhibited for all isolates with an efflux gene were 4 and 16 μg/ml, respectively. ERY, erythromycin.

CLI, clindamycin; AZM, azithromycin; SPY, spiramycin.

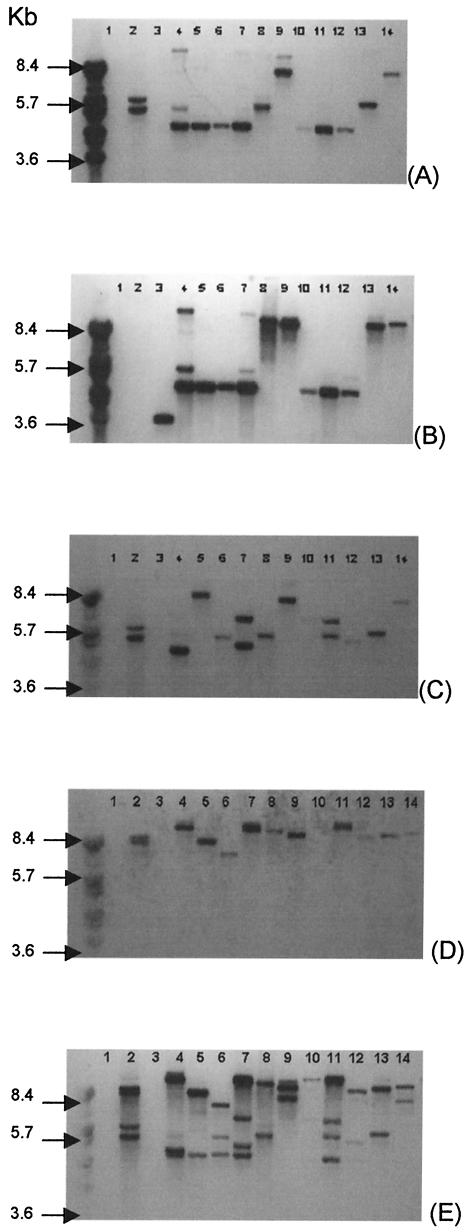

The presence of erythromycin resistance genes in oral streptococci is important because viridans group streptococci have been shown to cause systemic diseases (5, 18, 30) and they can disseminate the erythromycin resistance genes to other more pathogenic bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (2). In the course of this study we identified 12 isolates that, as well as being resistant to erythromycin, were also resistant to tetracycline. The filter-mating study showed that 4 of 12 isolates were able to transfer genes encoding resistance to both erythromycin [erm(B)] and tetracycline [tet(M)] to an E. faecalis recipient (Fig. 1). These two genes have previously been found on the same conjugative transposon, Tn1545 (27), which belongs to a larger class of conjugative transposons that include the well-studied element Tn916 (21). In this study we demonstrated that there is variation in the restriction pattern of the Tn1545-like elements (Fig. 1) and that these elements are widespread in the oral cavity and, more particularly, in oral streptococci. Moreover, we demonstrated that these elements are capable of intergenic transfer.

FIG. 1.

Southern blot hybridization analysis showing a linkage between tet(M), erm(B), int/xis, and aphA-3 genes in the parents and the transconjugants from the filter-mating experiments. The entire genomic DNA was digested with HindIII. BstEII-digested bacteriophage lambda DNA was used as the molecular size marker. Each panel shows the results of probing of the same blot with a different probespecific for tet(M) (A), erm(B) (B), the int/xis region from Tn916 (C), pPPM70 containing aphA-3 (D), and pAM120 (E). The lanes contain genomic DNA, as indicated: lanes 1, E. faecalis JH2/2; lanes 2, B. subtilis BS34A, lanes 3, S. pyogenes 02C1061 containing erm(B) (29); lanes 4, Streptococcus sp. strain E25-3; lanes 5, E. faecalis T1 (transconjugant from the mating of Streptococcus sp. strain E25-3 × E. faecalis JH2/2); lanes 6, Streptococcus sp. strain E31-2; lanes 7, E. faecalis T2 (transconjugant from the mating of Streptococcus sp. strain E31-2 × E. faecalis JH2/2); lanes 8, Streptococcus sp. strain E37-4; lanes 9, E. faecalis T3 (transconjugant from the mating of Streptococcus sp. strain E37-4 × E. faecalis JH2/2); lanes 10, Streptococcus sp. strain E38-2; lanes 11, E. faecalis T4 (transconjugant from the mating of Streptococcus sp. strain E38-2 × E. faecalis JH2/2); lanes 12, Streptococcus sp. strain E23-4; lanes 13, Streptococcus sp. strain E24-2; lanes 14, Streptococcus sp. strain E33-3.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joyce Sutcliffe, Amelia Tait-Kamradt, Julian I. Rood, and Marilyn C. Roberts for the provision of erythromycin-resistant strains.

This work was supported by project grant G99000875 from the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aminov, R. I., N. Garrigues-Jeanjean, and R. I. Mackie. 2001. Molecular ecology of tetracycline resistance: development and validation of primers for detection of tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protective proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aracil, B., M. Miñambres, J. Oteo, C. Torres, J. L. Gómez-Garcés, and J. I. Alós. 2001. High prevalence of erythromycin-resistant and clindamycin-susceptible (M phenotype) viridans group streptococci from pharyngeal samples: a reservoir of mef genes in commensal bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:592-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung, W. O., C. Werckenthin, S. Schwarz, and M. C. Roberts. 1999. Host range of the ermF rRNA methylase gene in bacteria of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cresti, S., M. Lattanzi, A. Zanchi, F. Montagnani, S. Pollini, C. Cellesi, and G. M. Rossolini. 2002. Resistance determinants and clonal diversity in group A streptococci collected during a period of increasing macrolide resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1816-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doern, G. V., M. J. Ferraro, A. B. Brueggemann, and K. L. Ruoff. 1996. Emergence of high rates of antimicrobial resistance among viridans group streptococci in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:891-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell, D. J., I. Morrissey, S. Bakker, and D. Felmingham. 2001. Detection of macrolide resistance mechanisms in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes using a multiplex rapid cycle PCR with microwell-format probe hybridization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:541-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fluit, A. D., M. R. Visser, and F. J. Schmitz. 2001. Molecular detection of antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:836-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gawron-Burke, C., and D. B. Clewell. 1984. Regeneration of insertionally inactivated streptococcal DNA fragments after excision of transposon Tn916 in Escherichia coli: strategy for targeting and cloning of genes from gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 159:214-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovanetti, E., M. P. Montanari, M. Mingoia, and P. E. Varaldo. 1999. Phenotypes and genotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains in Italy and heterogeneity of inducibly resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1935-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs, J. A., G. J. van Baar, N. H. H. J. London, J. H. T. Tjhie, L. M. Schouls, and E. E. Stobberingh. 2001. Prevalence of macrolide resistance genes in clinical isolates of the Streptococcus anginosus (“S. milleri”) group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2375-2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kataja, J., P. Huovinen, M. Skurnik, the Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance, and H. Seppälä. 1999. Erythromycin resistance genes in group A streptococci in Finland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:48-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luna, V. A., P. Coates, E. A. Eady, J. H. Cove, T. T. H. Nguyen, and M. C. Roberts. 1999. A variety of gram-positive bacteria carry mobile mef genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luna, V. A., M. Heiken, K. Judge, C. Ulep, N. Van Kirk, H. Luis, M. Bernardo, J. Leitao, and M. C. Roberts. 2002. Distribution of mef(A) in gram-positive bacteria from healthy Portuguese children. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2513-2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse, S. A., P. G. Lysko, L. McFarland, J. S Knapp, E. Sandstrom, C. Critchlow, and K. K. Holmes. 1982. Gonococcal strains from homosexual men have outer membranes with reduced permeability to hydrophobic molecules. Infect. Immun. 37:432-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1993. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 3rd ed. Approved standard M7-A3. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 16.Nawaz, M. S., S. A. Khan, A. A. Khan, F. M. Khambaty, and C. E. Cerniglia. 2000. Comparative molecular analysis of erythromycin-resistance determinants in staphylococcal isolates of poultry and human origin. Mol. Cell. Probes 14:311-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng, L.-K., I. Martin, M. Alfo, and M. Mulvey. 2001. Multiplex PCR for the detection of tetracycline resistance genes. Mol. Cell. Probes 15:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono, T., S. Shiota, K. Hirota, K. Nemoto, T. Tsuchiya, and Y. Miyake. 2000. Susceptibilities of oral and nasal isolates of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis to macrolides and PCR detection of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1078-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinert, R. R., A. Al-Lahham, M. Lemperle, C. Tenholte, C. Briefs, S. Haupts, H. H. Gerards, and R. Lütticken. 2002. Emergence of macrolide and penicillin resistance among invasive pneumococcal isolates in Germany. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts, A., G. Cheah, D. Ready, J. Pratten, M. Wilson, and P. Mullany. 2001. Transfer of Tn916-like elements in microcosm dental plaques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2943-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts, A., V. Braun, C. von Eichel-Streiber, and P. Mullany. 2001. Demonstration that the group II intron from the clostridial conjugative transposon Tn5397 undergoes splicing in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 183:1296-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts, A. P., C. Hennequin, M. Elmore, A. Collignon, T. Karjalainen, N. Minton, and P. Mullany. 2003. Development of an integrative vector for the expression of antisense RNA in Clostridium difficile. J. Microbiol. Methods 55:617-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts, M. C. 1998. Antibiotic resistance in oral/respiratory bacteria. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 9:522-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santagati, M., F. Iannelli, C. Cascone, F. Campanile, M. R. Oggioni, S. Stefani, and G. Pozzi. 2003. The novel conjugative transposon Tn1207.3 carries the macrolide efflux gene mef(A) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schalen, C., D. Gebreselassie, and S. Stahl. 1995. Characterization of an erythromycin resistance (erm) plasmid in Streptococcus pyogenes. APMIS 103:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seppäla, H., A. Nissinen, Q. Yu, and P. Huovinen. 1993. Three different phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32:885-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seral, C., F. J. Castillo, M. C. Rubio-Calvo, A. Fenoll, C. García, and R. Gómez-Lus. 2001. Distribution of resistance genes tet(M), aph3′-III, catpC194 and the integrase gene of Tn1545 in clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae harbouring erm(B) and mef(A) genes in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:863-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafer, W. M., L. F. Guymon, I. Lind, and P. F. Sparling. 1984. Identification of an envelope mutation (env-10) resulting in increased antibiotic susceptibility and pyocin resistance in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 25:767-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutcliffe, J., T. Grebe, A. Tait-Kamradt, and L. Wondrack. 1996. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2562-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, Y. C. Chen, S. W. Ho, and K. T. Luh. 1998. Antimicrobial susceptibility of viridans group streptococci in Taiwan with an emphasis on the high rates of resistance to penicillin and macrolides in Streptococcus oralis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:621-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villedieu, A., M. L. Diaz-Torres, N. Hunt, R. McNab, D. A. Spratt, M. Wilson, and P. Mullany. 2003. Prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes in oral bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:878-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber, P., J. Filipecki, E. Bingen, F. Fitoussi, G. Goldfarb, J. P. Chauvin, C. Reitz, and H. Portier. 2001. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of macrolide resistance in-group A streptococci isolated from adults with pharyngo-tonsillitis in France. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan, J.-J., H.-M. Wu, A.-H. Huang, H.-M. Fu, C.-T. Lee, and J.-J. Wu. 2000. Prevalence of polyclonal mefA-containing isolates among erythromycin-resistant group A streptococci in southern Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2475-2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]