Background: Metabolic diseases result from a combination of multiple genetic and environmental factors.

Results: High fat diet leads to chromatin remodeling in mice liver tissue in a strain-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Diet can induce changes in the epigenome thereby contributing to metabolic disease.

Significance: Environmental factors can contribute to complex disease progression through modifications to chromatin.

Keywords: Chromatin, Diet, Gene Regulation, Liver Metabolism, Metabolic Disease, Gene-environment Interaction

Abstract

Metabolic diseases result from multiple genetic and environmental factors. We report here that one manner in which environmental factors can contribute to metabolic disease progression is through modification to chromatin. We demonstrate that high fat diet leads to chromatin remodeling in the livers of C57BL/6J mice, as compared with mice fed a control diet, and that these chromatin changes are associated with changes in gene expression. We further show that the regions of greatest variation in chromatin accessibility are targeted by liver transcription factors, including HNF4α, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (CEBP/α), and FOXA1. Repeating the chromatin and gene expression profiling in another mouse strain, DBA/2J, revealed that the regions of greatest chromatin change are largely strain-specific and that integration of chromatin, gene expression, and genetic data can be used to characterize regulatory regions. Our data indicate dramatic changes in the epigenome due to diet and demonstrate strain-specific dynamics in chromatin remodeling.

Introduction

Diet is a key environmental factor involved in the development of many metabolic diseases. Indeed, excess consumption of calories from fats and refined carbohydrates has been associated with the development of obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and diabetes (1). One of the organs most affected by diet is the liver, which is a central site of many metabolic processes (2, 3). Given that obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and related metabolic disorders are major health concerns, understanding the genetic and environmental factors that drive metabolic diseases is of utmost importance.

In response to external stimuli such as nutrients, specific transcription factors (TFs)3 are engaged to regulate the expression of genes (4). Regions that are bound by TFs typically undergo chromatin modification, with rearrangement of local nucleosomes and modifications of histones in chromatin. These epigenetic changes can facilitate TF-DNA interaction (5). The accessibility of chromatin to TFs is cell type-specific and highly context-dependent (6, 7). As such, chromatin accessibility profiling has been utilized to identify key transcriptional programs that promote differentiation and to uncover regulatory sites that influence specific disease states such as type 1 diabetes (8, 9).

There are recent studies providing a link between environment and epigenetic marks (10, 11). For example, long term high fat (HF) diet can alter DNA methylation in the promoter of the mouse Mc4r gene and, intriguingly, the effect of this epigenetic modification is strain-specific (12). Furthermore, exercise has been shown to alter DNA methylation patterns in human adipose tissue (13). However, the mechanisms linking environment and chromatin structure remain unclear. We describe here how consumption of an HF diet leads to chromatin remodeling in the liver at regulatory regions of the genome in a strain-specific manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Four-to-six-week-old C57BL/6J (B6) and DBA/2J (D2) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and placed on either a high fat (Research Diets D12266B) or a control (Research Diets D12489B) diet for 8 weeks. Body fat percentage and body weight were tracked as described previously (14). The animal protocols for the study were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the UCLA and the City of Hope.

FAIRE-seq

After 8 weeks of feeding, mice were humanely euthanized, and livers were harvested. Formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) was performed as described previously (15). Isolated DNAs from two biological replicates in each condition and strain were barcoded and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 to produce 100 × 100-bp paired-end reads. Sequenced reads were aligned to the mouse genome (version mm9) using Bowtie2 with default options, except for the use of local alignment allowing for one mismatch in the seed sequence (16). Overall, we obtained 38–55 million aligned reads for B6 livers and 45–49 million aligned reads for the D2 livers. To confirm that the variability observed is not due to decreased genome mappability for the D2 genome as compared with the B6 (mm9 reference) genome, we aligned the sequenced reads to both the B6 reference genome and the D2 sequenced genome (17). We observed similar alignment rates for both genomes, indicating that the variability observed is not a technical artifact (B6 genome: B6, 91–98% alignment; D2, 94–98%; D2 genome: B6, 92–98%; D2, 87–96%).

Aligned reads were further filtered to exclude improperly paired reads and PCR duplicates. To identify FAIRE peaks (sites) from reads, F-seq was used with default parameters and 1000-bp feature length (18). We utilized the irreproducible discovery rate framework (19) to find reproducible peaks across replicates.

To find the most variable sites, the read density at each site was determined in control and HF livers and sites were ranked comparing the density of read counts in HF with control (HF/control). HNF4α chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) sites from B6 livers (20) and CTCF ChIP-seq sites (Mouse ENCODE) from B6 livers were obtained and overlapped with the most variable sites (37).

To assess accessibility differences of TF-bound and TF-unbound sites, HNF4α, CEBP/α, FOXA1, and CTCF sites were overlapped with all B6 FAIRE sites, and read densities comparing control with HF were determined (HF/control). Bootstrapping was used to determine the mean of each group.

ChIP-seq

ChIP experiments were performed with an anti-histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1) antibody (Abcam, ab8895) using standard ChIP and our published protocols (21). Sequencing libraries compatible with Illumina HiSeq 2500 technology were generated using Illumina protocols. We obtained 55 million reads for livers of C57BL/6J control and 71 million reads for C57BL/6J HF. Sequences were aligned to the mm9 reference genome as with FAIRE-seq reads. Read densities were determined for the most variable B6 chromatin sites accessible in HF liver (top 1000 ranked by -fold change HF/control), invariable regions (mid 1000), and most variable B6 chromatin sites in control liver (bottom 1000).

RNA-seq

RNAs were extracted from the same livers as those used for FAIRE-seq using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNAs were depleted of ribosomal RNA (Epicenter Ribo-ZeroTM magnetic kit, catalog number MRZH11124). Eluted RNAs were prepared for sequencing using Illumina protocols and sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 (Illumina) to generate 100 × 100-bp paired-end reads. We obtained 40–55 million reads for B6 livers and 50–55 million reads for D2 livers. The reads were aligned to the mm9 reference genome with TopHat (22) using the RefSeq gene annotation for transcript reference. Transcript abundance was quantified by fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) using Cufflinks (23). Cuffdiff (24) was used to identify differentially expressed (DE) transcripts from the RefSeq gene annotation. To identify enriched networks, data were analyzed through the use of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems).

To determine the statistical significance of proximity of variable FAIRE sites to DE genes, we randomly simulated the placement of 334 genes and 2000 variable sites across the genome 10,000 times. We then calculated the distances between the nearest gene site combinations within 200 kb. This analysis leads to an empirical p value for 121 genes and 2000 variable FAIRE sites within 200 kb of p < 1 × 10−4.

De Novo Motif Discovery

Motif discovery was performed with the top 1000 most variable sites (HF/control read densities) using DME2 (25). For both strains, we performed motif discovery on the top 1000 HF-specific FAIRE peaks with 10,000 random selected regions of length 500 bp used as background in DME. To mitigate the impact of strain-specific sequence variants on motif discovery, we created a pseudo-D2 reference genome by substituting known D2 single nucleotide variants into the mm9 reference genome (B6 genome) and used this for D2 analysis. We compared the de novo motifs to known TRANSFAC (26) motifs using MatCompare (27) with Kullback-Leibler divergence, as described previously (28). The motifs were then ranked by relative error rate (average of false positive and false negative rates adjusted for size of foreground and background sequences), as described previously (29).

Reporter Assays

To assess the enhancer function of the Lpin1 enhancer locus, both the B6 locus variant and the D2 locus variant were amplified from B6 genomic DNA and D2 genomic DNA, respectively, with the following primers: 5′-GCTAGCCTCGAGGATATCGGCAGGTCTTTGTGAGTTCAAGG-3′ and 5′-AGGCCAGATCTTGATATCCCTCCTTCCAAACTTTCCTCC-3′. The amplicons were inserted into the EcoRV locus of pGL4.23 (Promega), with In-Fusion reaction (Clontech). The two reporters and the control, pGL4.23 vector alone, were transfected into HepG2 cells with Lipofectamine 1000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cells were analyzed for expression of luciferase with the luciferase assay system (Promega). Expression of luciferase was quantified by the Tecan system.

RESULTS

C57BL/6J (B6) mice were placed on HF diet or control diet for 8 weeks. We profiled chromatin accessibility using FAIRE-seq in livers of B6 mice fed HF or control diets and identified reproducible peaks (sites) between biological replicates (see “Experimental Procedures”). We identified 28,484 sites in control and 28,253 sites in HF livers. We examined read densities at FAIRE sites for each diet and found high correlations between biological replicates (control: r2 = 0.99; HF: r2 = 0.99). Overall, we found 37,164 union FAIRE sites genome-wide with approximately two-thirds of these common across diets (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

HF diet chromatin remodeling. A, number of enriched regions of FAIRE for HF and control diets and genomic distribution by region. B, scatter plot of read counts at open chromatin sites. Shown are read counts (log 2) for each open chromatin site for control (x axis) and HF (y axis). The top 1000 open chromatin sites displaying the greatest -fold change in target counts are plotted in red. Con Tag, control tag. C, enriched Kegg Pathway terms for genes proximal to most variable FAIRE sites. D, scatter plot of distances between the 2000 most variable FAIRE sites and differentially expressed genes by their relative expression changes. 121 genes are within 200 kb (p < 0.0001). E, genome browser tracks displaying the Lpin1 locus with FAIRE-seq and RNA-seq tracks from livers of control and HF-fed mice, as well as Lpin1 eQTL SNPs (red). HF-specific FAIRE sites (highlighted yellow) overlap with eQTL SNPs associated with Lpin1. chr12, chromosome 12.

Given that open chromatin sites can be regulatory elements influencing gene expression (30), we examined the localization of variable sites relative to known genes. We isolated the top 1000 sites in terms of FAIRE-seq read density change for HF over control (Fig. 1B) and found these top sites to be within 10 kb of 666 RefSeq annotated genes. Notably, these genes are enriched for many metabolic pathways, including glycerolipid metabolism and insulin signaling pathway (Fig. 1C). We next addressed whether these variable regions may potentially serve as regulatory elements in cis to influence gene expression. Using RNA sequencing, we identified 334 DE genes (false discovery rate <0.1) in the same samples. Identification of enriched molecular networks with these DE genes indicated the top networks to be lipid metabolism, molecular transport, and small molecular biochemistry, consistent with these genes being influenced by an HF diet. We found 121 of the DE genes proximal (within 200 kb, p < 1 × 10−4) to the most variable FAIRE sites (2000 sites: top 1000 and bottom 1000 HF/control) (Fig. 1D). These data suggest potential interactions between the variable FAIRE sites and expression of proximal genes.

We further evaluated whether FAIRE sites identified by our analyses overlapped with liver expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP) (31). We found that 1492 of the ∼37,000 total open chromatin sites overlap with 1845 eQTL SNPs. Filtering the eQTL analysis for DE genes, we found 35 genes associated with 95 unique eQTLs overlapping 78 FAIRE sites. Interestingly, one of these genes, Lpin1, is also one of the top genes up-regulated in B6 mice fed HF diets. Lpin1 produces a phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme known to function in the triglyceride synthesis pathway (32). The Lpin1 locus contains a variable FAIRE site upstream from the transcriptional start site, overlapping several eQTL SNPs associated with Lpin1 expression (Fig. 1E).

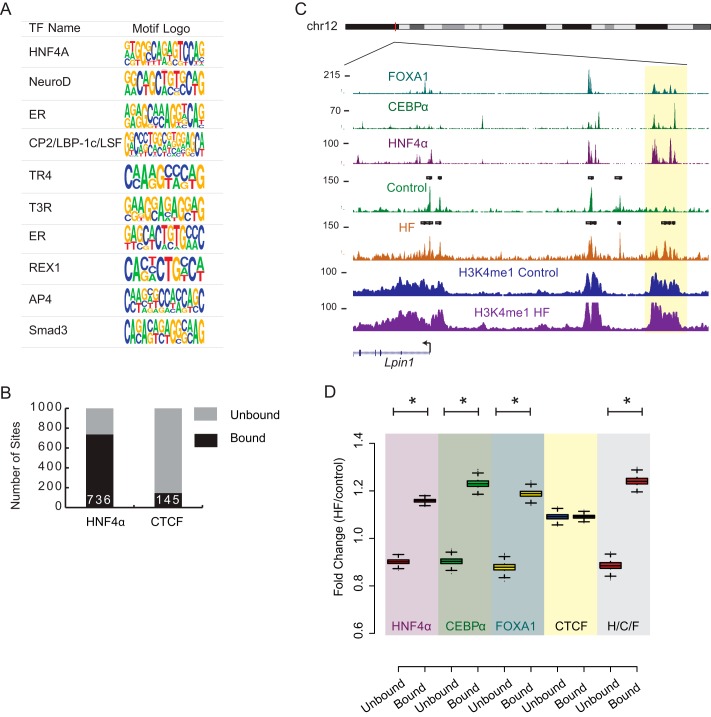

We next examined the most variable FAIRE sites for enriched motifs by performing de novo motif discovery (see “Experimental Procedures”). Many liver and developmental TF binding sites were enriched (Fig. 2A) with the top motif being HNF4α, a ligand-dependent TF required for liver-specific gene expression (33). Using HNF4α ChIP-seq data (20), we found that 736 of the top 1000 variable sites are bound by HNF4α (Fig. 2B). In comparison, CTCF bound to only 145 of the top 1000 variable sites. Given that HNF4α cooperatively binds to DNA with CEBP/α and FOXA1 in liver cells (20), we further explored the relationship between combinatorial binding of these factors and chromatin variation (Fig. 2C). We found that although HNF4α binds to 20,241 of the 28,484 open chromatin sites in control cells, FOXA1 and CEBP/α both also bind to the majority of the open chromatin sites (18,522 and 15,065 sites, respectively). Overall, all three TFs target the same 14,282 of the open chromatin sites in control cells. We asked whether FAIRE sites targeted by these TFs are in general more accessible in HF than in control. We examined the accessibility changes of these sites by comparing read density in HF and control at all FAIRE sites bound by HNF4α. As compared with HNF4α-unbound FAIRE sites, HNF4α-bound sites are more accessible with HF diet (Fig. 2D; p = 2 × 10−16; t test). Similar behavior was observed for FOXA1- and CEBP/α-bound sites, but not CTCF-bound sites (Fig. 2D, FOXA1 p = 2 × 10−16, CEBP/α p = 2 × 10−16, CTCF p = 0.95). Interestingly, we found that FAIRE sites targeted by all three TFs (H/C/F) display the greatest accessibility change (Fig. 2D, p = 2 × 10−16).

FIGURE 2.

Sites displaying increase in accessibility in B6 livers with HF diet are regulatory regions targeted by HNF4α, FOXA1, and CEBP/α. A, the top 10 motifs enriched in top 1000 variable sites in B6 genome. B, number of sites in the top 1000 variable sites in the B6 genome bound by HNF4α and CTCF. C, FAIRE-seq and ChIP-seq tracks for control and HF diets at the Lpin1 locus showing overlap of enrichment between FOXA1, CEBP/α, HNF4α, and H3K4me1 at variable chromatin sites. D, -fold change (HF read counts/control read counts) of B6 FAIRE sites classified by TF binding. Box plots show the median value, and whiskers show distribution of first and third quartile (*indicates p value < 0.0001).

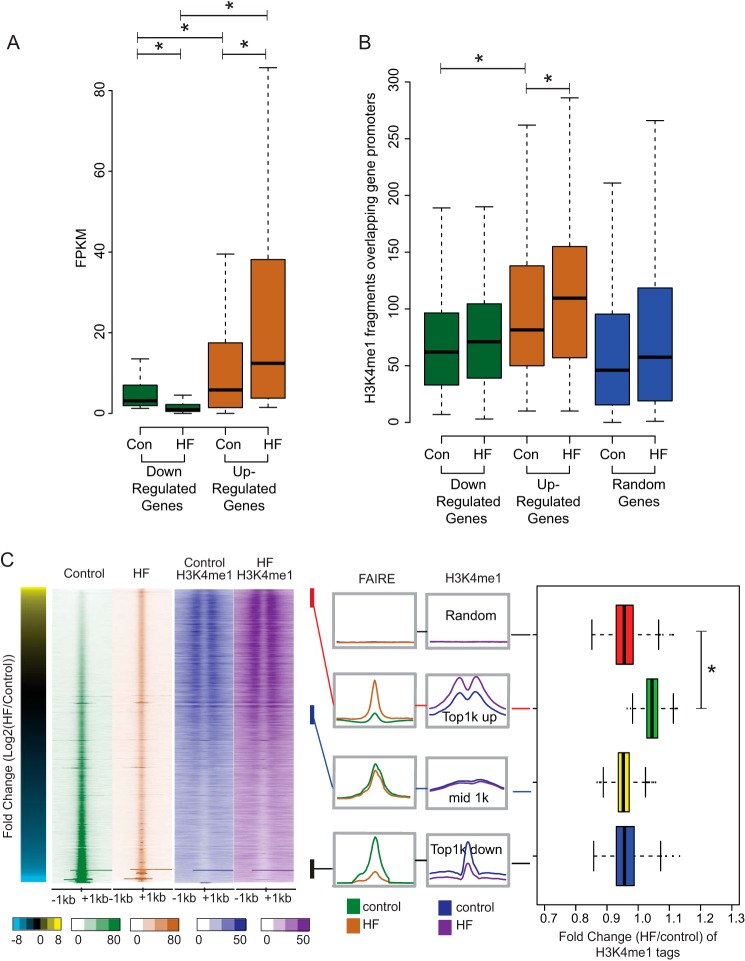

Given the striking overlap between liver TF binding and regions of chromatin accessibility changes under HF diet, we wanted to further investigate this relationship using a more unbiased approach. H3K4me1 is a characteristic mark of distal regulatory elements (34), and genomic profiles of this modification have been used to identify enhancer elements (35). We profiled H3K4me1 in the same samples using ChIP-seq (Fig. 2C). We first examined the relationship between gene expression and enrichment of H3K4me1 at promoters of differentially expressed genes. Examining the FPKM values for differentially up-regulated and down-regulated genes in both HF and control samples revealed that down-regulated genes start out with lower expression in control cells than up-regulated genes (Fig. 3A), indicating that up-regulated genes are already active in control cells. Consistent with this, consideration of the H3K4me1 read density in promoters of up-regulated and down-regulated genes indicated that in general, up-regulated genes have greater H3K4me1 signals than down-regulated genes in control cells, and the H3K4me1 levels are increased in HF (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Sites with increased chromatin accessibility also display local increase in H3K4me1 enrichment. A, gene expression (FPKM) for down-regulated and up-regulated genes in control (Con) and HF fed livers. B, enrichment of H3K4me1 fragments at promoters of down-regulated (199 genes), up-regulated (145 genes), and random (200 genes) genes in control and HF diet livers. (* indicates p value < 0.05). Box plots show the median value, and whiskers show distribution of first and third quartile. C, left, heat map of FAIRE and H3K4me1 densities at the union FAIRE sites for control and HF fed livers ranked by -fold change. Center, aggregate plots for FAIRE read counts and H3K4me1 read counts from four sets of 1000 sites: Random, 1000 randomly chosen site; Top1k up, most accessible in HF as compared with control; Top1k down, most accessible in control as compared with HF. Right, box plots of -fold change (HF/control) H3K4me1 read density from each of the set of sites. Box plots show the median value, and whiskers show distribution of first and third quartile (* indicates p value <0.01).

To examine the enrichment of H3K4me1 at variable FAIRE sites on the genome scale, we ranked all union FAIRE peaks for control and HF diet by the -fold change of HF over control and evaluated the FAIRE and H3K4me1 signal at these regions for both HF and control (Fig. 3C). Aggregate plots of the top 1000 regions, a set of 1000 peaks in the middle of the ranking, the bottom 1000, and a randomly selected set of 1000 regions reveal that the regions with the greatest change in accessibility are pre-marked with H3K4me1, and the most variable open chromatin sites become more enriched with H3K4me1 (Fig. 3C).

It has been previously reported that mice strains display heterogeneity in physiological responses to distinct diets (14, 36). We therefore next examined whether diet-induced chromatin variation in the liver is strain-specific by performing FAIRE profiling in livers of D2 mice under HF and control diet. Similar to B6 mice, D2 mice fed an HF diet for 8 weeks weighed more than control D2, as has been described previously (14). Oil Red O staining of livers from B6 and D2 mice revealed increases in hepatic lipid deposition in both strains for mice fed an HF diet as compared with control (Fig. 4A). We found similar numbers of open chromatin sites across the genome for D2 control and HF fed livers (26,661 control sites; 24,504 HF sites; 33,843 union sites; 17,030 common sites). As with the B6 strain, we found dramatic chromatin variability due to diet for D2 mice with approximately two-thirds of sites in common across conditions. Strikingly, however, the regions of greatest variability for D2 were largely distinct from the regions of variability for B6 (Fig. 4B), as exemplified by the Serpina5 locus (Fig. 4C). We verified that differences in chromatin variation for B6 and D2 were not due to decreased genome mappability for D2 by repeating the analysis with a pseudo-D2 reference genome (see “Experimental Procedures”). We performed de novo motif discovery with the top 1000 variable sites in the D2 genome and found that the enriched motifs are mostly distinct from those in the B6 top 1000 variable regions (Fig. 4D). Out of the top 10 enriched motifs, only SMAD3 was also identified in the B6 most variable regions, indicating that the regulatory networks involved in response to HF diet in the liver are largely distinct for B6 and D2.

FIGURE 4.

B6 and D2 display strain-specific diet-induced chromatin variations. A, Oil Red O (left) and H&E (right) staining from livers of B6 control, B6 HF, D2 control, and D2 HF livers. B, Venn diagram displaying overlap of B6 control-specific (not in HF) FAIRE sites and D2 control-specific sites (top), and between B6 HF-specific (not in control) FAIRE sites and D2 HF-specific sites (bottom). C, FAIRE-seq tracks displaying variations in chromatin accessibility between strains and diets. D, the top 10 motifs enriched in top 1000 variable sites in the D2 genome. E, left, heat map of normalized read counts at FAIRE sites for each group (see “Results” for details). Center, a schematic of sites in each group. Right, box plots of SNVs from each group as compared with randomly chosen sites of the same size and coverage. Box plots show the median value, and whiskers show distribution of first and third quartile (* indicates p value < 0.001).

We next investigated the possibility that local DNA sequence variation contributes to strain-specific chromatin variability. We stratified FAIRE sites into the following groups: Group A, HF-specific sites in B6 alone; Group B, HF-specific sites common to B6 and D2; Group C, HF-specific sites in D2 alone; Group D, diet-independent sites for B6 not observed in D2; and Group E, diet-independent sites for D2 not observed in B6. Each group of sites was assessed for overlap with single nucleotide variants (SNVs) between the B6 and D2 genome builds and compared with random sites of equal size and coverage (Fig. 4E). As expected, Group D and Group E, which contain strain-specific FAIRE sites that are not affected by diet, are statistically enriched for genetic variation as compared with random sites. Interestingly, Group A and Group C are also enriched for genetic variation as compared with random sites. In total, within Group A and Group C, ∼50% of strain-specific chromatin variation sites contain SNVs. Given that the other ∼50% of the strain-specific chromatin variation sites do not contain SNVs, there are clearly other mechanisms for chromatin variation involved as well.

To begin to understand the contribution of sites that display strain-specific chromatin variability to the physiology of the cell, we utilized the Genome Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) to predict function for cis-regulatory elements (38). The top Gene Ontology (GO) biological process for Group A sites is “Positive regulation of JAK-STAT cascade,” and this prediction was unique to Group A. Interestingly, JAK-STAT signaling pathway has been shown to be involved in the development of liver fibrosis (39), a phenotype that differs between the two strains of mice (40). These data suggest that strain-specific chromatin sites can contribute to strain-specific phenotypes.

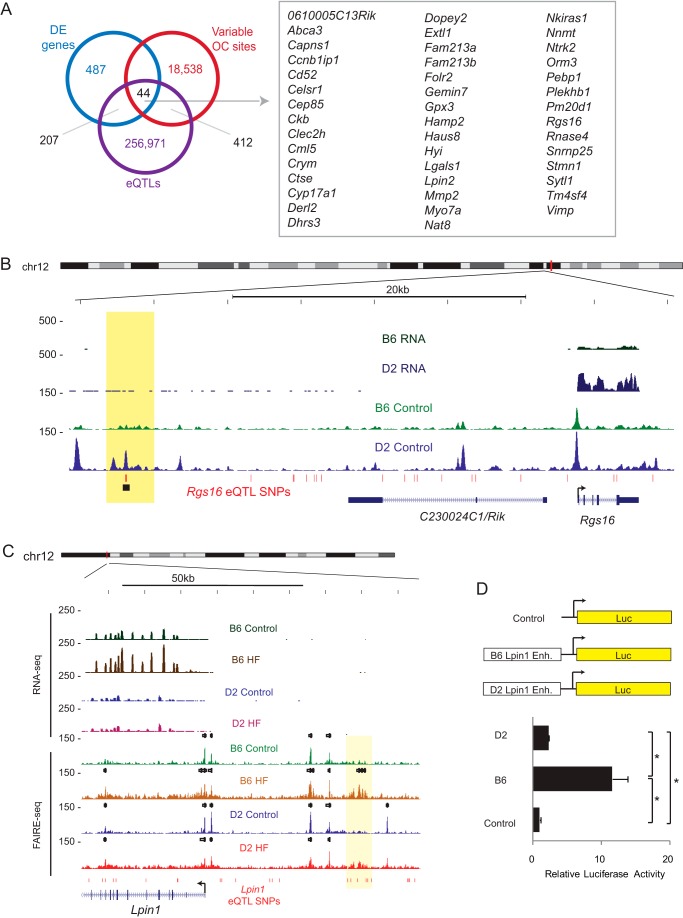

Given the enrichment of SNVs at strain-specific FAIRE sites, we asked whether these sites were enriched for liver eQTL SNPs from the HMDP. We started by considering the 487 genes that are differentially expressed in control diets between B6 and D2 livers. Of these 487 genes, 207 have eQTL SNPs within 1 Mb of the gene body. Of these 207 genes, 163 have genotypes that are dimorphic between B6 and D2, and of these, 44 genes have variable FAIRE sites overlapping dimorphic eQTL SNPs (Fig. 5A). Another 44 of these 207 genes have common genotypes between B6 and D2, and of these, only 3 have variable FAIRE sites overlapping eQTL SNPs (p = 0.004; Fisher exact test), indicating that genes with variable genotypes are more likely to have variable chromatin accessibility profiles. One of the genes with variable genotype and chromatin accessibility between B6 and D2 is the regulator of G protein signaling 16, Rgs16 (Fig. 5B), which has three eQTL SNPs overlapping a D2 HF-specific FAIRE site ∼30 kb upstream of the transcription start site. Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins help control hepatic lipid homeostasis, and Rgs16 has been shown to signal for glucose production for inhibition of fatty acid oxidation (41, 42).

FIGURE 5.

Integration of chromatin accessibility, eQTL, and gene expression data identifies regions of regulatory variation. A, overlapping eQTL, chromatin accessibility, and gene expression changes identify 44 genes with regulatory variation in the liver between B6 and D2. OC sites, open chromatin sites. B, Rgs16 is differentially expressed between livers of B6 and D2 mice and has 281 eQTL SNPs associated with expression in the HMDP. Of these, 3 overlap a region of variable chromatin between B6 and D2 (highlighted). C, genome browser tracks displaying the Lpin1 locus with RNA-seq and FAIRE-seq tracks from control and HF-fed mice, with Lpin1 eQTL SNPs in red. The B6-specific, HF-specific FAIRE site is highlighted in yellow. D, schematic of luciferase (Luc) constructs to examine enhancer activity of B6 Lpin1 enhancer (Enh.) variant and D2 Lpin1 enhancer variant (top). Bar graph shows relative luciferase activity, normalized to control construct. Error bars represent S.E. (*, p value <0.05, Student's t test, n = 3).

These results indicate that the integration of chromatin, gene expression, and SNP data can be used to characterize regulatory variants. To evaluate this, we chose a B6 HF-specific FAIRE site overlapping an eQTL ∼40 kb upstream of the Lpin1 locus (Fig. 5C) and generated enhancer constructs to test the enhancer function of these sites. We found that although the D2 variant of this enhancer site can slightly increase expression of the luciferase reporter relative to control vector, the B6 genotype has 4-fold higher enhancer activity at this site (Fig. 5D).

DISCUSSION

Complex metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease result from multiple genetic and environmental factors. Although genetic studies have revealed many loci predisposing individuals to risk of these diseases, they explain a very small fraction of the total trait variance. Clearly, environmental factors and gene-by-environment factors are very important (14). We have demonstrated here that one mechanism whereby environmental factors can influence disease risk is through chromatin remodeling. We found that diet elicits changes in chromatin accessibility, and our results show that the regions undergoing the greatest chromatin remodeling in the livers of HF-fed mice are bound by liver regulatory factors, indicating a modulation of liver regulatory networks under HF diet. We further show that we can pinpoint specific loci, such as the FAIRE site upstream from Lpin1 that may function to specifically regulate Lpin1 in a diet-specific manner. Characterization of loci such as these is critical to understanding the mechanisms that contribute to gene regulation and ultimately the pathways involved in disease progression.

We have also demonstrated that the regions of chromatin remodeling in livers of mice subjected to HF diet are strain-specific. The fact that distinct sites of the B6 and D2 genome display variation under diet suggests that different networks may be engaged in response to diet in each strain. These data also uncover a genetic component in how the environment can impact disease progression and suggest the existence of genetic-epigenetic crosstalk. Recently, it has been shown that local sequence variation may account for ∼30% of chromatin variation in erythroblasts from distinct inbred mice in a single condition (43). In comparison, our data indicate that up to 50% of chromatin variations may be attributed to local sequence variation. These differences may be attributed to the fact that our studies include additional sites influenced by diet. We have also examined the potential function of these sites of strain-specific chromatin variability and found that the JAK-STAT pathway may be positively regulated in the B6 mice under HF diet, but not for D2 mice under the same diet. Future studies addressing the role of these sites in the development of physiological differences between the two strains will be important to our understanding of chromatin variation and phenotype.

Finally, further studies into the role of the chromatin variations identified in this study and genetic variants will illuminate distinct relationships between DNA sequence and chromatin variation. Indeed, although limited by variation in human-bred mouse populations, we are able to show that specific FAIRE sites containing genetic variation are linked to specific genes such as Lpin1 and Rgs16. These results further elucidate regulatory mechanisms associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity and hepatic steatosis and could lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kirti Bhatt for assistance with staining and other members of the Schones and Natarajan laboratories for helpful discussions and comments. Research reported in this publication included work performed in the Pathology and Integrative Genomics Cores of the City of Hope supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA33572.

This work was supported by Schaeffer endowment funds and National Institutes of Health Grants K22HL101950 (to D. E. S.), T32DK007571-24 (to A. L.), R01HL106089, R01HL087864, and RO1DK065073 (to R. N.), and HL28482 and DK094311 (to A. J. L.).

All sequencing datasets presented in this paper have been deposited into the NCBI GEO repository under accession number GSE55581.

- TF

- transcription factor

- HF

- high fat

- B6

- C57BL/6J

- D2

- DBA/2J

- FAIRE

- formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements

- DE

- differentially expressed

- eQTL

- expression quantitative trait loci

- H3K4me1

- histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation

- CEBP/α

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α

- FPKM

- fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- SNV

- single nucleotide variant

- seq

- sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Friedman J. M. (2009) Obesity: causes and control of excess body fat. Nature 459, 340–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lara-Castro C., Garvey W. T. (2008) Intracellular lipid accumulation in liver and muscle and the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 37, 841–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen J. C., Horton J. D., Hobbs H. H. (2011) Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332, 1519–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wellen K. E., Thompson C. B. (2010) Cellular metabolic stress: considering how cells respond to nutrient excess. Mol. Cell 40, 323–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Voss T. C., Hager G. L. (2014) Dynamic regulation of transcriptional states by chromatin and transcription factors. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 69–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cuddapah S., Jothi R., Schones D. E., Roh T. Y., Cui K., Zhao K. (2009) Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 19, 24–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fu Y., Sinha M., Peterson C. L., Weng Z. (2008) The insulator binding protein CTCF positions 20 nucleosomes around its binding sites across the human genome. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waki H., Nakamura M., Yamauchi T., Wakabayashi K., Yu J., Hirose-Yotsuya L., Take K., Sun W., Iwabu M., Okada-Iwabu M., Fujita T., Aoyama T., Tsutsumi S., Ueki K., Kodama T., Sakai J., Aburatani H., Kadowaki T. (2011) Global mapping of cell type-specific open chromatin by FAIRE-seq reveals the regulatory role of the NFI family in adipocyte differentiation. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaulton K. J., Nammo T., Pasquali L., Simon J. M., Giresi P. G., Fogarty M. P., Panhuis T. M., Mieczkowski P., Secchi A., Bosco D., Berney T., Montanya E., Mohlke K. L., Lieb J. D., Ferrer J. (2010) A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat. Genet. 42, 255–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keating S. T., El-Osta A. (2012) Chromatin modifications associated with diabetes. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 5, 399–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddy M. A., Natarajan R. (2011) Epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic vascular complications. Cardiovasc. Res. 90, 421–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Widiker S., Karst S., Wagener A., Brockmann G. A. (2010) High-fat diet leads to a decreased methylation of the Mc4r gene in the obese BFMI and the lean B6 mouse lines. J. Appl. Genet. 51, 193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rönn T., Volkov P., Davegårdh C., Dayeh T., Hall E., Olsson A. H., Nilsson E., Tornberg A., Dekker Nitert M., Eriksson K. F., Jones H. A., Groop L., Ling C. (2013) A six months exercise intervention influences the genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in human adipose tissue. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parks B. W., Nam E., Org E., Kostem E., Norheim F., Hui S. T., Pan C., Civelek M., Rau C. D., Bennett B. J., Mehrabian M., Ursell L. K., He A., Castellani L. W., Zinker B., Kirby M., Drake T. A., Drevon C. A., Knight R., Gargalovic P., Kirchgessner T., Eskin E., Lusis A. J. (2013) Genetic control of obesity and gut microbiota composition in response to high-fat, high-sucrose diet in mice. Cell Metab. 17, 141–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giresi P. G., Kim J., McDaniell R. M., Iyer V. R., Lieb J. D. (2007) FAIRE (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 17, 877–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keane T. M., Goodstadt L., Danecek P., White M. A., Wong K., Yalcin B., Heger A., Agam A., Slater G., Goodson M., Furlotte N. A., Eskin E., Nellåker C., Whitley H., Cleak J., Janowitz D., Hernandez-Pliego P., Edwards A., Belgard T. G., Oliver P. L., McIntyre R. E., Bhomra A., Nicod J., Gan X., Yuan W., van der Weyden L., Steward C. A., Bala S., Stalker J., Mott R., Durbin R., Jackson I. J., Czechanski A., Guerra-Assunção J. A., Donahue L. R., Reinholdt L. G., Payseur B. A., Ponting C. P., Birney E., Flint J., Adams D. J. (2011) Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature 477, 289–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boyle A. P., Guinney J., Crawford G. E., Furey T. S. (2008) F-Seq: a feature density estimator for high-throughput sequence tags. Bioinformatics 24, 2537–2538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Q. H., Brown J. B., Huang H. Y., Bickel P. J. (2011) Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann. Appl. Stat. 5, 1752–1779 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stefflova K., Thybert D., Wilson M. D., Streeter I., Aleksic J., Karagianni P., Brazma A., Adams D. J., Talianidis I., Marioni J. C., Flicek P., Odom D. T. (2013) Cooperativity and rapid evolution of cobound transcription factors in closely related mammals. Cell 154, 530–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leung A., Trac C., Jin W., Lanting L., Akbany A., Sætrom P., Schones D. E., Natarajan R. (2013) Novel long noncoding RNAs are regulated by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 113, 266–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trapnell C., Pachter L., Salzberg S. L. (2009) TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25, 1105–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M. J., Salzberg S. L., Wold B. J., Pachter L. (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trapnell C., Hendrickson D. G., Sauvageau M., Goff L., Rinn J. L., Pachter L. (2013) Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 46–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith A. D., Sumazin P., Zhang M. Q. (2005) Identifying tissue-selective transcription factor binding sites in vertebrate promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1560–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wingender E., Chen X., Hehl R., Karas H., Liebich I., Matys V., Meinhardt T., Prüss M., Reuter I., Schacherer F. (2000) TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 316–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schones D. E., Sumazin P., Zhang M. Q. (2005) Similarity of position frequency matrices for transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21, 307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith A. D., Sumazin P., Das D., Zhang M. Q. (2005) Mining ChIP-chip data for transcription factor and cofactor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21, i403–i412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martinez M. J., Smith A. D., Li B. L., Zhang M. Q., Harrod K. S. (2007) Computational prediction of novel components of lung transcriptional networks. Bioinformatics 23, 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gross D. S., Garrard W. T. (1988) Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57, 159–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bennett B. J., Farber C. R., Orozco L., Kang H. M., Ghazalpour A., Siemers N., Neubauer M., Neuhaus I., Yordanova R., Guan B., Truong A., Yang W. P., He A., Kayne P., Gargalovic P., Kirchgessner T., Pan C., Castellani L. W., Kostem E., Furlotte N., Drake T. A., Eskin E., Lusis A. J. (2010) A high-resolution association mapping panel for the dissection of complex traits in mice. Genome Res. 20, 281–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finck B. N., Gropler M. C., Chen Z., Leone T. C., Croce M. A., Harris T. E., Lawrence J. C., Jr., Kelly D. P. (2006) Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1α/PPARα regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 4, 199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sladek F. M., Zhong W. M., Lai E., Darnell J. E., Jr. (1990) Liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-4 is a novel member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Genes Dev. 4, 2353–2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heintzman N. D., Hon G. C., Hawkins R. D., Kheradpour P., Stark A., Harp L. F., Ye Z., Lee L. K., Stuart R. K., Ching C. W., Ching K. A., Antosiewicz-Bourget J. E., Liu H., Zhang X., Green R. D., Lobanenkov V. V., Stewart R., Thomson J. A., Crawford G. E., Kellis M., Ren B. (2009) Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature 459, 108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zentner G. E., Tesar P. J., Scacheri P. C. (2011) Epigenetic signatures distinguish multiple classes of enhancers with distinct cellular functions. Genome Res. 21, 1273–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Funkat A., Massa C. M., Jovanovska V., Proietto J., Andrikopoulos S. (2004) Metabolic adaptations of three inbred strains of mice (C57BL/6, DBA/2, and 129T2) in response to a high-fat diet. J. Nutr 134, 3264–3269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mouse ENCODE Consortium, Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Snyder M., Hardison R., Ren B., Gingeras T., Gilbert D. M., Groudine M., Bender M., Kaul R., Canfield T., Giste E., Johnson A., Zhang M., Balasundaram G., Byron R., Roach V., Sabo P. J., Sandstrom R., Stehling A. S., Thurman R. E., Weissman S. M., Cayting P., Hariharan M., Lian J., Cheng Y., Landt S. G., Ma Z., Wold B. J., Dekker J., Crawford G. E., Keller C. A., Wu W., Morrissey C., Kumar S. A., Mishra T., Jain D., Byrska-Bishop M., Blankenberg D., Lajoie B. R., Jain G., Sanyal A., Chen K. B., Denas O., Taylor J., Blobel G. A., Weiss M. J., Pimkin M., Deng W., Marinov G. K., Williams B. A., Fisher-Aylor K. I., Desalvo G., Kiralusha A., Trout D., Amrhein H., Mortazavi A., Edsall L., McCleary D., Kuan S., Shen Y., Yue F., Ye Z., Davis C. A., Zaleski C., Jha S., Xue C., Dobin A., Lin W., Fastuca M., Wang H., Guigo R., Djebali S., Lagarde J., Ryba T., Sasaki T., Malladi V. S., Cline M. S., Kirkup V. M., Learned K., Rosenbloom K. R., Kent W. J., Feingold E. A., Good P. J., Pazin M., Lowdon R. F., Adams L. B. (2012) An encyclopedia of mouse DNA elements (Mouse ENCODE). Genome Biol. 13, 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McLean C. Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S. L., Schaar B. T., Lowe C. B., Wenger A. M., Bejerano G. (2010) GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 495–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mair M., Blaas L., Österreicher C. H., Casanova E., Eferl R. (2011) JAK-STAT signaling in hepatic fibrosis. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 16, 2794–2811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hall R. A., Liebe R., Hochrath K., Kazakov A., Alberts R., Laufs U., Bohm M., Fischer H.-P., Williams R. W., Schughart K., Weber S. N., Lammert F. (2014) Systems genetics of liver fibrosis: identification of fibrogenic and expression quantitative trait loci in the BXD murine reference population. PloS One 9, e89279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang J., Pashkov V., Kurrasch D. M., Yu K., Gold S. J., Wilkie T. M. (2006) Feeding and fasting controls liver expression of a regulator of G protein signaling (Rgs16) in periportal hepatocytes. Comp. Hepatol. 5, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pashkov V., Huang J., Parameswara V. K., Kedzierski W., Kurrasch D. M., Tall G. G., Esser V., Gerard R. D., Uyeda K., Towle H. C., Wilkie T. M. (2011) Regulator of G protein signaling (RGS16) inhibits hepatic fatty acid oxidation in a carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP)-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15116–15125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hosseini M., Goodstadt L., Hughes J. R., Kowalczyk M. S., de Gobbi M., Otto G. W., Copley R. R., Mott R., Higgs D. R., Flint J. (2013) Causes and consequences of chromatin variation between inbred mice. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]