Abstract

The development of resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine by Plasmodium parasites is a major problem for the effective treatment of malaria, especially P. falciparum malaria. Although the molecular basis for parasite resistance is known, the factors promoting the development and transmission of these resistant parasites are less clear. This paper reports the results of a quantitative comparison of factors previously hypothesized as important for the development of drug resistance, drug dosage, time of treatment, and drug elimination half-life, with an in-host dynamics model of P. falciparum malaria in a malaria-naïve host. The results indicate that the development of drug resistance can be categorized into three stages. The first is the selection of existing parasites with genetic mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase or dihydropteroate synthetase gene. This selection is driven by the long half-life of the sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine combination. The second stage involves the selection of parasites with allelic types of higher resistance within the host during an infection. The timing of treatment relative to initiation of a specific anti-P. falciparum EMP1 immune response is an important factor during this stage, as is the treatment dosage. During the third stage, clinical treatment failure becomes prevalent as the parasites develop sufficient resistance mutations to survive therapeutic doses of the drug combination. Therefore, the model output reaffirms the importance of correct treatment of confirmed malaria cases in slowing the development of parasite resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

Drug resistance is becoming an increasingly important factor in the effective treatment of malaria. High levels of resistance to chloroquine have forced some countries to switch their first-line drug to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP, trade name Fansidar). However, resistance to this drug combination is developing fast, with treatment failure being reported in Africa, Asia, Indonesia, and South America (5, 7, 16, 20, 31).

Pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine act synergistically to inhibit two enzymes important in the parasite's folate biosynthetic pathway, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and dihydropteroate synthetase (DHPS) (13). Point mutations in the DHFR and DHPS genes confer resistance to pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine, respectively, with decreasing in vitro Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility related to the number of mutations in each gene (6, 30, 34). The same mutations have been linked to treatment failure in the clinical setting (5, 7, 20, 33); the presence of mutations in DHFR appear to be more important in causing treatment failure than DHPS mutations (5). Although the molecular basis for SP resistance is understood, the factors promoting the development and transmission of these mutants are less clear.

It has been suggested that drug pharmacokinetics (12), overusage of drugs (28), cross-resistance between drugs (14), and inadequate treatment through inappropriate prescription or administration, noncompliance, or poor absorption (28, 36) contribute to the development of resistance. The timing of treatment relative to the initiation of an immune response in the patient has also been hypothesized as important in developing resistance (10), as have host immunity and transmission level (13, 38). Although individual factors involved in the evolution of drug resistance have been identified, the relative importance of these factors has not been reported in a quantitative format. This paper considers the influence of drug dosage and the timing of treatment on the rate of SP treatment failure predicted by a simulation model of P. falciparum infection. It also quantifies the relative importance of these factors in the development of SP resistance resulting in treatment failure. The selective pressure exerted by the long half-life of SP is also considered relative to its role in promoting the development and spread of resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A previously reported in-host dynamics model (9) was used to simulate a P. falciparum infection in a malaria-naive human host. Simulations were conducted with the model parameter set obtained from fitting the model to data from patients infected with the El Limon and Santee Cooper P. falciparum parasite strains (9). This parameter set was used because it had previously been validated against various clinical outcomes (9). Parasite mutation was assumed to be a stochastic event occurring in either the DHFR or DHPS gene or both at a rate of 10−9 mutations/gene/replication (25). Drug treatment was included in the model by reducing the parasite load in accordance with the drug dosage and time since treatment. A Poisson distribution with mean Pi × Tm,j was used to estimate the number of surviving parasites, where Pi is the number of parasites in the host on day i and Tm,j is the probability of a parasite's surviving the effect of drug dosage j, m days posttreatment.

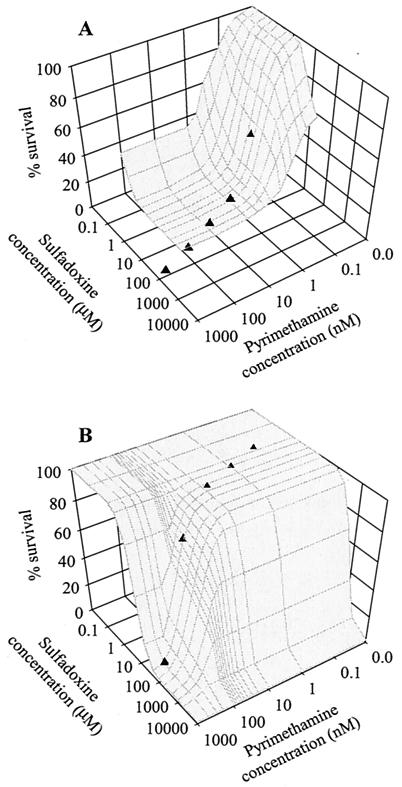

The probability of parasites' surviving at various time points after treatment was determined by combining information from SP isobolograms (32) and dose-response curves (39). Isobolograms for parasites containing triple mutations (3M) in both the DHFR and DHPS genes (3M/3M) and for parasites containing a triple mutation in DHFR and the wild-type DHPS gene (3M/WT) were digitized. These isobolograms contain the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for various SP concentrations in the presence of 45 nM folic acid. To estimate the probability of parasites' surviving, the dose-response curve for pyrimethamine (24) was used to estimate scaling factors, from which an IC50 in the isobolograms could be converted to an ICx (where x = 0,…, 100). The results from three dose-response curves, two from wild-type parasites (24, 39) and one from parasites containing a single mutation in DHFR (24), were averaged to achieve the scaling factors. It was assumed that these scaling factors were also applicable to sulfadoxine.

To calculate the survival probabilities for mutation combinations other than 3M/3M and 3M/WT, the following were assumed: a single mutation at codon 108 in the DHFR gene results in a ≈50-fold increase in the IC50 relative to the wild-type parasite (3, 5, 6, 25, 26); a double mutation in DHFR results in a ≈170-fold increase in the IC50 relative to the wild type (4, 6, 22, 26); a triple mutation in the DHFR gene results in a ≈700-fold increase in the IC50 compared to the wild type (3, 6); and single, double, and triple mutations in DHPS result in ≈15-, ≈45-, and ≈800-fold increases relative to the wild type in the IC50 for sulfadoxine, respectively (22, 34). These values were used to scale the isobolograms to represent other DHFR-DHPS mutation combinations.

Plasma drug concentrations were estimated by assuming that the average maximum concentration of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine in the plasma of an adult after a standard three-tablet dose of Fansidar (75 mg of pyrimethamine and 1,500 mg of sulfadoxine) is 2.58 μM and 612 μM, respectively (35). Between 80 and 90% of pyrimethamine and 90 and 95% of sulfadoxine bind to plasma proteins (17), leaving approximately 0.52 and 60 μM unbound pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine, respectively, to act on the parasites. The elimination half-life of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine was assumed to be 95.5 and 184 h, respectively (35). With this information, the drug concentration at various time points following treatment was determined. Three treatment regimes were simulated: the recommended three-tablet dose of Fansidar that reaches 100% of the expected plasma concentration, the recommended three-tablet dose of Fansidar that reaches 80% of the expected plasma concentration (e.g., poor absorption of drug), and a two-tablet dose of Fansidar. Figure 1 illustrates how the parasite genotype and drug kinetics were combined to estimate the probability of parasites' surviving drug treatment.

FIG. 1.

Parasite survival in the presence of various SP concentrations. (A) The wild-type (WT/WT) and (B) the 3M DHFR/3M DHPS parasite genotypes. Symbols on each of the surfaces indicate the SP concentrations that can be expected within a host 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 days following treatment with a standard three-tablet dose of SP.

To assess the selective pressure exerted by the long elimination half-life of SP, simulations were conducted to mimic individuals with and without residual drug in the blood (treated and untreated populations, respectively). Residual drug concentrations were tracked for 48 days following treatment. After this time period, it was assumed that the drug concentration had no effect on the parasites and that the status of an individual converted to untreated. It was also assumed that individuals in the treated population received a three-tablet (100% effective) SP dose that cured the initial infection and that the threshold for activation of the nonspecific immune response was higher for subsequent infections than for the initial infection (8). As the probability of receiving an infectious bite during the 48 days following treatment is dependent on the transmission intensity in the area, the methodology outlined in the Appendix was used to estimate the ratio of treated to untreated individuals for a given transmission intensity.

RESULTS

SP treatment failure rates were calculated for 144 different scenarios (three treatment regimes × three treatment times × 16 DHFR-DHPS mutation combinations), with 1,000 simulations of the model run for each scenario. Treatment times were selected to encompass the various states of the anti-Plasmodium falciparum EMP1 immune response (Table 1). Treatment failure was defined as incomplete clearance (elimination) of parasites from the host.

TABLE 1.

Pathology of simulated P. falciparum infections caused by the El Limon and Santee Cooper parasite strains treated at three different time points

| Time of treatment (days after start of blood-stage infection) | Avg parasitemia (no./μl) | Simulated symptoms and host responsesa |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | ∼250 | Typically no fever; nonspecific immunity and specific immunity not yet triggered |

| 10 | ∼2,700-3,000 | Fever; antibodies to some dominant EMP1 variants triggered |

| 12 | ∼3,000-5,500 | Severe fever; antibodies to most (if not all) EMP1 variants expressed early in the infection have been triggered |

EMP1, P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1.

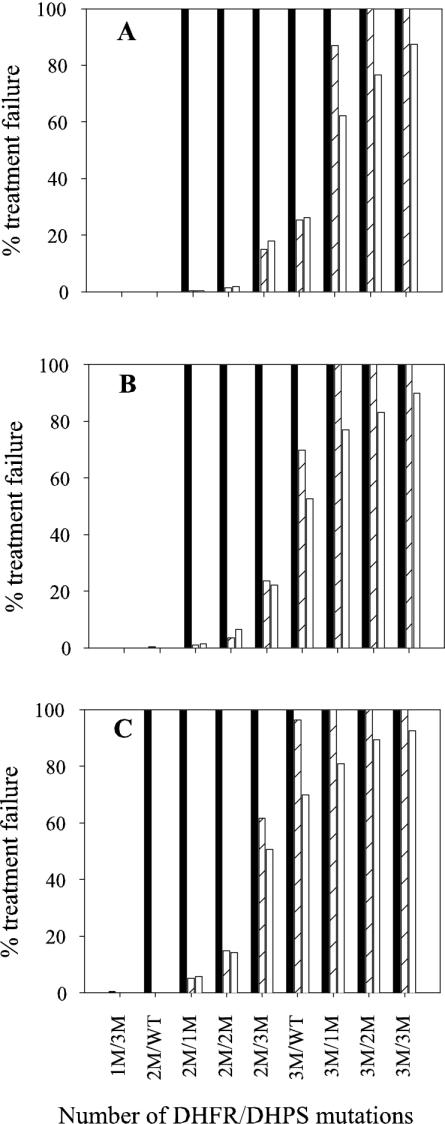

The treatment failure rates predicted from the model are displayed in Fig. 2 for the various treatment and genotype combinations. As expected, the failure rate was zero for infections with wild-type parasites and those with minimal mutations, increasing to 100% as the number of mutations in DHFR and DHPS increased. Mutations in the DHFR gene were more influential on treatment failure than mutations in DHPS. For the double mutation (2M) DHFR/WT DHPS genotype (2M/WT), neither the time of treatment during the infection nor the dose had any noticeable effect on the failure rate. However, combining treatment at day 8 with suboptimal dosing resulted in high levels of treatment failure. Beginning with the 2M/WT genotype, the addition of one extra mutation in DHPS was sufficient to cause a dramatic increase in treatment failure if treatment was administered on day 8, irrespective of the drug dosage. High numbers of mutations in DHFR (e.g., 3M/WT) were prone to significantly increased treatment failure rates if SP was administered 8 days after the start of the asexual infection or if a suboptimal treatment dosage was delivered. Even at high levels of mutation, treatment was still effective for approximately 13% of infections if the patient was dosed with the recommended concentration of drug upon presentation with symptoms. Overall, a trend toward the onset of treatment failure occurred with fewer mutations when suboptimal SP treatment was delivered. Irrespective of the drug dosage for infections that failed treatment, the time interval between treatment and the appearance of recrudescent parasites decreased with increasing levels of parasite mutation (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Predicted treatment failure rates for various parasite genotypes when infections are treated with (A) three SP tablets, (B) three SP tablets which achieve 80% of the expected plasma concentration, and (C) two SP tablets. Genotypes not included in the graph had no simulated treatment failures. Simulations were conducted with treatment at 8 (solid bars), 10 (striped bars), or 12 days (open bars) after the start of the blood-stage infection.

A feature common to all simulations was the development of a subpopulation of parasites carrying mutations additional to the parental population. In most simulations, this subpopulation remained a negligible proportion of the total parasite burden. However, when treatment was administered 8 days after the start of the asexual infection, the subpopulation of mutated parasites was occasionally selected within the host (Table 2). The proportion of simulations in which this selection occurred increased with increasing number of mutations in the parental population and also with decreasing drug dosage.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of recrudescent infections with >1% of parasites carrying an additional mutation compared to the infecting parasite and with treatment administered 8 days after the start of asexual infection

| DHFR/DHPS genotype of infecting parasite | % of simulations with >1% of recrudescent parasites carrying an extra mutation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Three tablets achieving 100% of expected concn | Three tablets achieving 80% of expected concn | Two tablets achieving 100% of expected concn | |

| 1M/3M | 0.0a | 0.0a | 0.5a,b |

| 2M/WT | 0.0 | 0.3b | 1.7 |

| 2M/1M | 1.5 | 2.6 | 4.0 |

| 2M/2M | 2.6 | 6.5 | 15.6 |

| 2M/3M | 10.2a | 18.6a | 20.9a |

Additional mutations can only occur in the DHFR gene.

All infections that recrudesced had >1% of parasites carrying an additional mutation compared to the infecting parasite.

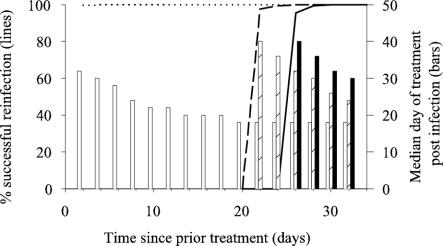

The presence of residual drug in the blood protected individuals against reinfection for up to 26 days depending on the genotype of the infecting parasite (Fig. 3). Various degrees of protection against reinfection were provided for all genotypes with the exception of 2M DHFR/2M DHPS and parasites containing triple mutations in the DHFR gene (irrespective of the DHPS genotype). Protection against reinfection for longer than 14 days was only provided with wild-type parasites and parasites having WT DHRF/1M, 2M, and 3M DHPS genotypes. In most simulations, the onset of symptoms was delayed when residual drug was present in the blood. The magnitude of this delay decreased with increasing mutation level and/or time since treatment (Fig. 3). However once infected, the overall treatment failure rate for each of the DHFR-DHPS genotype combinations simulated did not differ between cases with or without residual drug in their blood.

FIG. 3.

Effect of residual drug on reinfection rates and development of clinical malaria. The percentage of reinfections that were successful by wild-type parasites (WT/WT) and parasites with a double mutation in either the DHFR (2M/WT) or DHPS (WT/2M) gene following SP treatment is indicated by the solid, dotted, and dashed lines, respectively. The bars indicate the mean time until the appearance of symptoms requiring treatment following reinfections occurring between 2 and 32 days post-SP treatment.

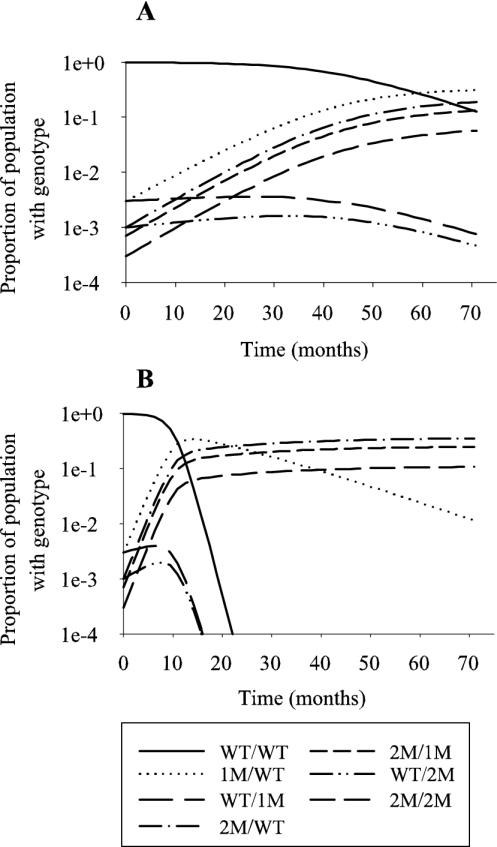

As a consequence of the protection afforded by the residual drug, a change in the prevalence of each parasite genotype over time was noted; the prevalence of the wild-type and wild-type DHFR/mutated DHPS parasites decreased with a corresponding increase in the other genotype combinations. The rate of selection of the more mutated parasites depended on the transmission rate of the region (Fig. 4). A high transmission rate appeared to accelerate the selection of mutated parasites.

FIG. 4.

Illustrative changes in the prevalence of parasite genotypes caused by SP use in (A) low-transmission regions (≈1.8 infectious bites/year) and (B) high-transmission regions (≈18 infectious bites/year). In each region, the ratio of genotypes prior to the introduction of SP treatment was set to 9,900:30:30:10:10:10:7:3 for WT/WT, 1M/WT, WT/1M, 1M/1M, 2M/WT, WT/2M, 2M/1M, and 2M/2M parasites, respectively. The 1M/1M genotype was omitted because its prevalence curve was indistinguishable from the curve of the WT/1M genotype parasites.

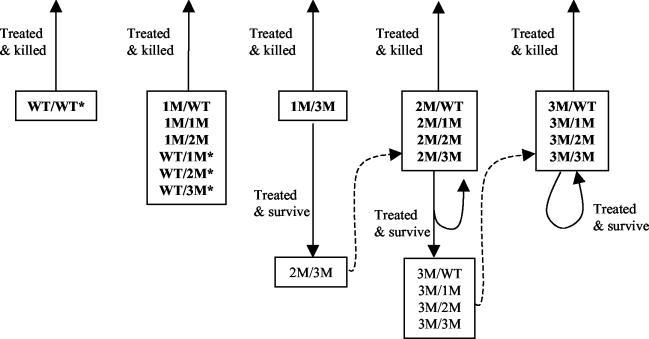

Assessing the relative importance of various factors in the development of drug resistance depended on the level of mutation within the parasite population at any time. A schematic diagram showing the fate of parasites following treatment with SP indicates that there was no mechanism for individual wild-type and singly mutated parasites to advance their mutation level (Fig. 5). However, this group of parasites was subject to strong negative selection pressure caused by the long elimination half-life of SP. In contrast, after parasites achieved a single mutation in DHFR and a triple mutation in DHPS (1M/3M), treatment 8 days after the start of the blood-stage infection provided an environment in which parasites with additional mutations had a selective advantage within the host. Since there was no mechanism for flow of parasites between mutation groups early in the development of resistance, the initial presence of parasites with mutated DHFR and/or DHPS genes was fundamental for drug resistance to develop. Given that genetic mutation is a random occurrence, it would be expected that some parasites harbor these mutations, even with very low mutation rates and the absence of drug pressure.

FIG. 5.

Schematic illustration of the evolution of SP resistance. The fate of parasites following treatment with SP is indicated for each genotype. At low levels of mutation, there is no mechanism for advancement of mutation level. However, the presence of residual drug concentrations provides a strong selection pressure against the indicated genotypes (*). At intermediate mutation levels, early suboptimal treatment provides an environment where parasites with additional mutations may be selected for within the host, leading to treatment failure. At high mutation levels, parasites are often able to survive therapeutic doses of SP, causing treatment failure.

DISCUSSION

The rapid development of parasite resistance to antimalaria drugs is a fundamental problem for the effective treatment of malaria. Understanding the factors promoting the development of resistance is the first step to prolonging the effective therapeutic life of a drug. Here we have presented a comparative analysis of some factors previously implicated as important in the development of resistance by analyzing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment failure rates predicted by an in-host dynamics model of P. falciparum malaria. The selection pressure exerted by this long-acting drug combination on the distribution of parasite genotypes was also investigated.

The results presented need to be viewed relative to the assumptions of the model. The first and probably most important consideration is that the model mimics a P. falciparum infection in a malaria-naïve host such as a child, visitor, or immigrant from a nonmalarious area. Since semi-immune individuals typically respond better to treatment than hosts not previously exposed to malaria (37), the model output would be expected to overestimate the treatment failure rate for semi-immune individuals. The second consideration relates to modeling a single clone of parasites. In areas of high transmission, multiple infections are likely; the model ignores the effect of parasite recombination, which can act to reduce the probability that resistance will be retained by the parasite (11). Lastly, the determination of the speed with which resistance develops is restricted to limited situations in which everyone within a population of malaria-naïve hosts is treated when they become sick. This may occur in situations where a population is relocated into a malarious area and closely monitored. In other situations where only a proportion of the people are treated, the selection pressure on parasites would be expected to be less than that indicated. As such, the model predictions reported here represent a worse-case scenario for a naïve population.

Since the identification of molecular markers for SP resistance, numerous field studies have assessed the correlation between genetic mutations and treatment failure. A number of studies have attributed SP treatment failure to infection with parasites having at least a double mutation in DHFR coupled with a single mutation in the DHPS gene (1, 5, 7, 15, 20). The model results presented here are in agreement with these findings. A more detailed comparison of treatment failure rates for specific parasite genotypes indicated that the model predictions for mutation levels of 2M/1M or above encompass reported treatment failure rates at 3 days and 7 days posttreatment (4, 19). The simulation results also suggest that even within a naïve host, processes such as antigenic variation and the corresponding immune response that develops to it during the course of an infection may play a role in reducing the treatment failure rate. This type of interaction may explain the apparent discrepancy between the proportion of parasite isolates that are resistant in vitro and the much reduced incidence of in vivo treatment failure (1).

The model's prediction that treatment failure rates increase with suboptimal dosing agrees with field data from Kenyan children (29). The same study reported that treatment failure rates were higher in individuals who had been treated with SP in the 5 weeks prior to the current infection (29). Our predictions suggest that the increase in treatment failure observed may be due to the different length of protection afforded against reinfection for different parasite genotypes, so that only resistant parasites can reinfect individuals shortly after SP treatment.

The model output indicates that for the parasite characteristics considered, treatment of infections caused by parasites having at least two mutations in DHFR prior to the triggering of the specific immune response (day 8 in the model) resulted in 100% treatment failure, whereas treatment after the stimulation of the specific immune response (either day 10 or 12 in the model) resulted in lower failure rates. This result appears to contradict the general belief that treatment of an infection at a smaller parasite burden (earlier time) reduces the chances of treatment failure. However, closer examination of the factors influencing the survival of parasites following treatment indicates that the infectious load is not the only factor pertinent to determining treatment failure. This is particularly true for infections caused by parasites having at least two mutations in DHFR, for which even optimal doses of SP are often not sufficient to kill 100% of parasites. In these situations, the parasite burden is severely reduced following treatment but gradually increases again as the drug concentrations within the host wane. This high treatment failure rate can be improved by the development of a specific immune response to the variant antigens that can mop up the parasites not killed by the drug combination. Therefore, treating infections early so as to have a smaller biomass is important for infections with parasites having no or low levels of mutation but is predicted to lead to increased treatment failure in infections caused by highly resistant parasites.

For the parasite characteristics assumed in this model, the specific immunity for most of the expressed var genes has been triggered by day 12, coinciding with the onset of symptoms, while no or few antibodies have been triggered by day 8. However, these values are an approximation only and may vary for different parasites depending on the rate of var gene switching, the number of parasites expressing a variant required to trigger the specific immunity, and also the pyrogenic threshold (dictating the onset of symptoms).

In the majority of simulations in which recrudescence occurred, the model predicted that the recrudescent parasites exhibited the same genotype as those in the initial infection. However, parasites with additional mutations could become prominent under certain circumstances. These results agree with in vitro data showing no significant difference between the mean IC50 values of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine for paired blood samples taken from patients prior to SP treatment and from recrudescent infections post-SP treatment (18). Epidemiological data collected from malaria-infected children also indicated that in the majority of SP treatment failures, the recrudescent parasites had the same DHFR-DHPS genotype as the parasites in the initial infection (23; A. Nzila, personal communication).

Although the model is able to predict the frequency of parasites with additional mutations becoming dominant within a host, it is not able to estimate the probability of these newly developed parasites being transmitted through the mosquito to a new human host and subsequently becoming successfully established in a community. Recent reports demonstrate that gene flow rather than new mutation is responsible for the high level of resistance mutations in the parasite's DHFR and DHPS in Africa (27) and DHFR in southeast Asia (21). This suggests that the successful establishment of these new mutated parasites in the community is a rare event.

The model predicted that the long half-life of SP provides strong selective pressure against parasites carrying wild-type DHFR, potentially resulting in the rapid decline of the wild-type DHFR genotype in high-transmission areas. Such a process may account for the rapid decrease (from 18 to 4% in 12 months) in the prevalence of the wild-type DHFR genotype in Tanzania (16). The model output also suggested that the infrequent observation of sulfadoxine-resistant but pyrimethamine-sensitive parasites in the field (18) may result from the greater selection pressure against wild-type DHFR/mutant DHPS parasites compared to mutant DHFR/wild-type DHPS parasites.

Although the long half-life of SP exerts a selection pressure favoring mutated parasites, it also has the potential to reduce the infection and transmission rate by providing some protection against reinfection. The actual magnitude of the potential decrease in transmission rate is related to the prevalence of parasites carrying mutations in DHFR and DHPS and the proportion of the population receiving treatment and therefore having residual drug in their blood. Such a decrease in transmission rate could partially offset the selection pressure caused by the long elimination half-life of SP. The current model, which was designed to mimic the in-host dynamics of P. falciparum infections in a naïve individual, requires further development to explore these types of interactions. Only then can the overall impact of SP treatment within a human population be assessed.

Hastings et al. (12) proposed that the evolution of drug resistance could be split into two distinct phases: the transition from wild-type parasites to slightly mutated forms that are less sensitive to the drug, but are still killed by therapeutic concentrations and the conversion from low to high levels of mutation and the emergence of clinical resistance to the drug. It was hypothesized that the level of drug usage in the population was a fundamental factor during the first stage, while the proportion of infections treated within the population was the primary factor influencing the second stage in the evolution of drug resistance (12). The results reported here support this general hypothesis, but suggest that there is an additional intermediate stage in which suboptimal treatment of low-grade infections is important.

The results presented indicate that the best protocol for slowing the development of drug resistance to SP is optimal treatment of individuals after the development of clinical symptoms and subsequent confirmation of malaria. The presumptive treatment of malaria by health workers or through self-medication has the potential to increase the speed with which resistance develops for two reasons. First, presumptive treatment of illnesses thought to be malaria creates a situation in which a larger proportion of the population has drug in their blood. This acts to increase the selection pressure against wild-type parasites, although it may also result in a reduction in transmission. Second, presumptive treatment of nonimmune individuals who are not ill from malaria but do carry low-grade resistant parasitemia due to a developing malaria infection results in treatment being administered prior to the triggering of any specific immune response. This has the potential to cause treatment failure, possibly selecting for a more resistant parasite population within the host.

The speed with which drug resistance develops is dictated by the prevalence of parasites carrying mutations in DHFR and/or DHPS when the drug is first introduced. Therefore, resistance to SP would be expected to develop more rapidly in areas where drugs targeting the same active site as either pyrimethamine or sulfadoxine have been or are being used (2, 14). Although these drugs may not necessarily be used to treat malaria, their use will ultimately result in malaria parasites' being exposed to subtherapeutic doses, providing an environment promoting the development of resistance to a component of the SP combination. Examples of this include the use of sulfa drugs to treat bacterial infections (31) or the use of trimethoprim, which cross-reacts with pyrimethamine, as a prophylactic treatment for opportunistic infections in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals (14). Since drug resistance is a problem for many infectious diseases, a combined effort from disease specialists is required to devise an overall treatment strategy which best suits the needs of an individual country or region. In this way, the effective life of many drugs used to treat multiple diseases may be extended.

The simulation model used in this analysis of SP resistance is equally applicable to the investigation of the development of drug resistance to other antimalarial combinations. A prime candidate for such analysis is the chlorproguanil-dapsone combination. With the pharmacokinetic data specific for this drug combination, it would be interesting to speculate on the factors promoting resistance and explore the likelihood of treatment failure with chlorproguanil-dapsone in regions already experiencing SP failure. Such analysis would provide useful information on the likely success and effective life of this new drug combination.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI-47500-03. Michelle Gatton was supported in part by a University of Queensland Postdoctoral Research Fellowship.

We thank Dennis Kyle for helpful discussions and valuable comments on the manuscript.

APPENDIX

Assuming that people were treated when they had a nonspecific immune response sufficient to cause a fever, the proportion of the population who received an infectious bite that would result in a blood-stage infection was calculated (equation 1). For the untreated population, rk,i = 1, while in the treated population, 0 ≤ rk,i ≤ 1, depending on the drug concentration within the blood at the time of infection,

|

(1) |

where Si is the proportion of the population receiving an infectious bite on day i which will eventuate in a developing blood-stage infection (i = 0,…, 48 and i = 0 represents the day that the initial infection was treated), b is the probability of receiving an infectious bite (per day), pk is the proportion of parasites carrying DHFR/DHPS genotype k, and rk,j is the probability of a blood-stage infection developing if infected with parasites of DHFR-DHPS genotype k on day j. The proportion of the population becoming infected and failing SP treatment within the 48-day period is defined as

|

(2) |

where fk is the probability of treatment failure for infections with parasites of genotype k.

Ignoring parasite recombination and assuming that every person who becomes sick is treated and has an equal opportunity to transmit parasites to a susceptible mosquito, the change in the prevalence of genotypes can be tracked over time by using equation 3. The superscripts U and T represent the values of previously defined variables (S and r) in the untreated and treated populations, respectively. A time period representing 48 days is used in these calculations.

|

(3) |

where pk,q is the proportion of parasites with genotype k at time period q, V is the proportion of the population not treated with SP within the last 48 days, and dUk,q−1 is the proportion of untreated patients infected with parasites of genotype k during the time period

|

(4) |

and pTk,q−1 is the proportion of treated patients infected with parasites of genotype k during the time period

|

(5) |

If all individuals who become sick are treated, the ratio of untreated to treated populations is

|

(6) |

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubouy, A., S. Jafari, V. Huart, F. Migot-Nabias, J. Mayombo, R. Durand, M. Bakary, J. LeBras, and P. Deloron. 2003. DHFR and DHPS genotypes of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Gabon correlate with in vitro activity of pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, but not with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment efficacy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basco, L. K., and J. Le-Bras. 1997. In vitro sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum to anti-folinic agents (trimethoprim, pyrimethamine, cycloguanil): a study of 29 African strains. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 90:90-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basco, L. K., and P. Ringwald. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of malaria in Yaounde, Cameroon. VI. Sequence variations in the Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene and in vitro resistance to pyrimethamine and cycloguanil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basco, L. K., R. Tahar, A. Keundjian, and P. Ringwald. 2000. Sequence variation in the genes encoding dihydropteroate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase and clinical response to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 182:624-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basco, L. K., R. Tahar, and P. Ringwald. 1998. Molecular basis of in vivo resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in African adult patients infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 42:1811-1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowman, A. F., M. J. Morry, B. A. Biggs, G. A. Cross, and S. J. Foote. 1988. Amino acid changes linked to pyrimethamine resistance in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9109-9113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskandarian, A., H. Keshavarz, L. K. Basco, and F. Mahboudi. 2002. Do mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydropteroate synthase and dihyrofolate reductase confer resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in Iran? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96:96-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatton, M. L., and Q. Cheng. 2002. Evaluation of the pyrogenic threshold for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in naive individuals. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatton, M. L. and Q. Cheng. 2004.. Investigating antigenic variation and other parasite-host interactions in Plasmodium falciparum infection in naïve hosts. Parasitology 128:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gatton, M. L., W. Hogarth, and A. Saul. 2001. Time of treatment influences the appearance of drug-resistant parasites in Plasmodium falciparum infections. Parasitology 123:537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings, I. M. and U. D'Alessandro. 2000. Modelling a predictable disaster: the rise and spread of drug-resistant malaria. Parasitol. Today 16:340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hastings, I. M., W. M. Watkins, and N. J. White. 2002. The evolution of drug-resistant malaria: the role of drug elimination half-life. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 357:505-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins Sibley, C., J. E. Hyde, P. F. Sims, C. V. Plowe, J. G. Kublin, E. K. Mberu, A. F. Cowman, P. A. Winstanley, W. M. Watkins, and A. M. Nzila. 2001. Pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: what next? Trends Parasitol. 17:582-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iyer, J. K., W. K. Milhous, J. F. Cortese, J. G. Kublin, and C. V. Plowe. 2001. Plasmodium falciparum cross-resistance between trimethoprim and pyrimethamine. Lancet 358:1066-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelinek, T., A. H. Kilian, G. Kabagambe, and F. Von-Sonnenburg. 1999. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine in Uganda: correlation with polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61:463-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jelinek, T., A. M. Rønn, M. M. Lemnge, J. Curtis, J. Mhina, M. T. Duraisingh, I. C. Bygbjerg, and D. C. Warhurst. 1998. Polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and dihydropteroate synthetase (DHPS) genes of Plasmodium falciparum and in vivo resistance to sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine in isolates from Tanzania. Trop. Med. Int. Health 3:605-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martindale, W. 1993. The extra pharmacopoeia, 30th ed., p. 205, 406. Pharmaceutical Press, London, England.

- 18.Mberu, E. K., M. K. Mosobo, A. M. Nzila, G. O. Kokwaro, C. H. Sibley, and W. M. Watkins. 2000. The changing in vitro susceptibility pattern to pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Kilifi, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutabingwa, T., A. Nzila, E. Mberu, E. Nduati, P. Winstanley, E. Hills, and W. Watkins. 2001. Chlorproguanil-dapsone for treatment of drug-resistant falciparum malaria in Tanzania. Lancet 358:1218-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagesha, H. S., Din-Syafruddin, G. J. Casey, A. I. Susanti, D. J. Fryauff, J. C. Reeder, and A. F. Cowman. 2001. Mutations in the pfmdr1, dhfr and dhps genes of Plasmodium falciparum are associated with in-vivo drug resistance in West Papua, Indonesia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nair, S., J. T. Williams, A. Brockman, L. Paiphun, M. Mayxay, P. N. Newton, J. P. Guthmann, F. M. Smithuis, T. T. Hien, N. J. White, F. Nosten, and T. J. Anderson. 2003. A selective sweep driven by pyrimethamine treatment in Southeast Asian malaria parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:1526-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ndounga, M., L. K. Basco, and P. Ringwald. 2001. Evaluation of a new sulfadoxine sensitivity assay in vitro for field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95:55-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nzila, A. M., E. Nduati, E. K. Mberu, C. Hopkins Sibley, S. A. Monks, P. A. Winstanley, and W. M. Watkins. 2000. Molecular evidence of greater selective pressure for drug resistance exerted by the long-acting antifolate pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine compared with the shorter-acting chlorproguanil/dapson on Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum. J. Infect. Dis. 181:2023-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paget-McNicol, S. 2002. Estimation of mutation and switching rates in Plasmodium falciparum genes. Ph.D. thesis. University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia.

- 25.Paget-McNicol, S., and A. Saul. 2001. Mutation rates in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 122:497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson, D. S., Milhous, W. K., and Wellems, T. E. 1990. Molecular basis of differential resistance to cycloguanil and pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3018-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roper, C., R. Pearce, B. Bredenkamp, J. Gumede, C. Drakeley, F. Mosha, D. Chandramohan, and B. Sharp. 2003. Antifolate antimalarial resistance in southeast Africa: a population-based analysis. Lancet 361:1174-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson, J. A., E. R. Watkins, R. N. Price, L. Aarons, D. E. Kyle, and N. J. White. 2000. Mefloquine pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models: implications for dosing and resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3414-3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terlouw, D. J., J. M. Courval, M. S. Kolczak, O. S. Rosenberg, A. J. Oloo, P. A. Kager, A. A. Lal, B. L. Nahlen, and F. O. Ter-Kuile. 2003. Treatment history and treatment dose are important determinants of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine efficacy in children with uncomplicated malaria in Western Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 187:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triglia, T., J. G. Menting, C. Wilson, and A. F. Cowman. 1997. Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are responsible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13944-13949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasconcelos, K. F., C. V. Plowe, C. J. Fontes, D. Kyle, D. F. Wirth, L. H. Pereira da Silva, and M. G. Zalis. 2000. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihdrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase of isolates from the Amazon Region in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 95:721-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, P., R. K. Brobey, T. Horii, P. F. Sims, and J. E. Hyde. 1999. Utilization of exogenous folate in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and its critical role in antifolate drug synergy. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1254-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, P., C. S. Lee, R. Bayoumi, A. Djimde, O. Doumbo, G. Swedberg, L. D. Dao, H. Mshinda, M. Tanner, W. M. Watkins, P. F. Sims, and J. E. Hyde. 1997. Resistance to antifolates in Plasmodium falciparum monitored by sequence analysis of dihydropteroate synthetase and dihydrofolate reductase alleles in a large number of field samples of diverse origins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 89:161-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, P., M. Read, P. F. Sims, and J. E. Hyde. 1997. Sulfadoxine resistance in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum is determined by mutations in dihydropteroate synthetase and an additional factor associated with folate utilization. Mol. Microbiol. 23:979-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weidekamm, E., H. Plozza-Nottebrock, I. Forgo, and U. C. Dubach. 1982. Plasma concentrations of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine and evaluation of pharmacokinetic data by computerized curve fitting. Bull. W.H.O. 60:115-122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White, N. 1999. Antimalarial drug resistance and combination chemotherapy. Phil. Trans. R Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 354:739-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White, N. J. 1997. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1413-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White, N. J., and W. Pongtavornpinyo. 2003. The de novo selection of drug-resistant malaria parasites. Proc. R Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 270:545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winstanley, P. A., E. K. Mberu, I. S. Szwandt, A. M. Breckenridge, and W. M. Watkins. 1995. In vitro activities of novel antifolate drug combinations against Plasmodium falciparum and human granulocyte CFUs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:948-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]