Abstract

We report that the amiloride analogues 5-(N,N-hexamethylene)amiloride and 5-(N,N-dimethyl)amiloride inhibit, at micromolar concentrations, the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in cultured human blood monocyte-derived macrophages. These compounds also inhibit the in vitro activities of the HIV-1 Vpu protein and might represent lead compounds for a new class of anti-HIV-1 drugs.

The amiloride analogues 5-(N,N-hexamethylene)amiloride (HMA) and 5-(N,N-dimethyl)amiloride (DMA) (Fig. 1) block the ion channel formed by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) Vpu protein (4). Vpu (17) is a small multifunctional integral membrane protein that enhances HIV-1 budding by an unknown mechanism associated with its ion channel activity (5, 6, 9, 11, 16). The demonstration that HMA also inhibits the budding and release of virus-like particles (VLPs) from HeLa cells coexpressing HIV-1 Gag and Vpu indicates a link between the Vpu ion channel activity and the budding mechanism (4). Amiloride itself does not inhibit either Vpu channels or VLP budding (4). Here, we report that HMA and DMA (but not amiloride) also inhibit in vitro the replication of HIV-1BaL in cultured human blood monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), cells that are believed to play a principal role in the pathogenesis of human HIV-1 infections (2), that act as a virus reservoir, and that are resistant to current antiretroviral therapies (7).

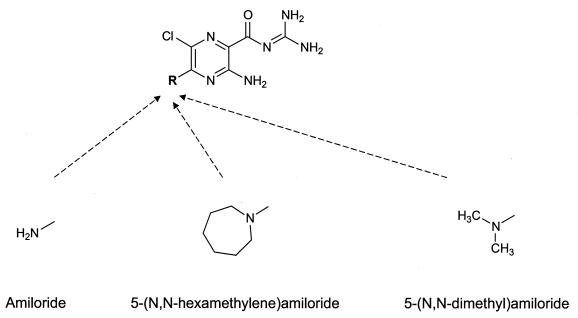

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of amiloride, HMA, and DMA.

Cytotoxicities of HMA, DMA, and amiloride.

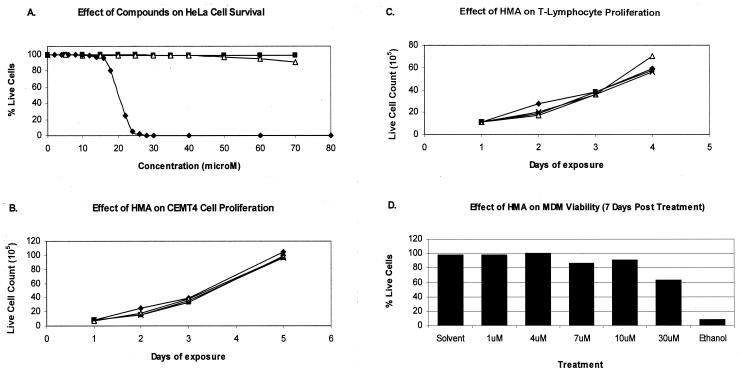

Before the compounds were tested for their abilities to inhibit virus, the cytotoxicities of the compounds against cultured HeLa cells, CEMT4 cells, primary T lymphocytes, and MDMs were characterized. After incubation in the presence of each compound, the cells were tested for viability by either trypan blue exclusion or, in the case of MDMs, the more sensitive technique of propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry. HMA at 10 μM did not affect the live cell counts or the rate of proliferation of HeLa or CEMT4 cells or primary T lymphocytes (Fig. 2A to C). Figure 2D illustrates that in the presence of 10 μM HMA, 90% of the MDMs remained viable after 7 days, whereas significant cytotoxicity occurred in the presence of 30 μM HMA. Similar results were seen in three other experiments, in which 10 μM HMA was not toxic, while 30 μM caused a marked decrease in viable cell counts. After prolonged exposure to 10 μM HMA for 14 days (data not shown), the majority (>80%) of MDMs remained viable. DMA and amiloride were found to be less toxic than HMA.

FIG. 2.

Effects of HMA on cell viability and proliferation. (A) HeLa cell monolayers were incubated in the presence of various concentrations of HMA (diamonds), DMA (squares), or amiloride (triangles) for 3 days. The cells were then detached from tissue culture wells by treatment with trypsin and were incubated with trypan blue to stain the dead cells. The proportion of live cells was determined by counting in a hemocytometer. (B and C) Effects of HMA at 0.1 μM (squares), 1.0 μM (triangles), and 10 μM (crosses) on the proliferation of CEMT4 cells (B) and T lymphocytes (C) cultured for 5 days. The ordinate shows the number of live cells after trypan blue staining. The diamonds indicate the proliferation of cells in drug-free control cultures. (D) Five-day-old MDMs (approximately 106 cells) were exposed to various concentrations of HMA for 7 days before they were harvested and stained with PI, followed by flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. HMA was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to give a concentration of 500 mM and was then serially diluted 1:9 in 0.1 N HCl and 1:4 in phosphate-buffered saline prior to final dilution in growth medium (RF10/10 [RPMI containing 10% human type AB serum and 10% fetal calf serum]). Solvent controls were prepared in the same way in which the compound was diluted. Ethanol (100%) was used as a positive control. The results are presented as the proportion of viable cells (PI negative) in HMA-treated cultures relative to the number of viable cells in the medium control.

Overall, these experiments revealed that 10 μM HMA is well tolerated, and we therefore chose that concentration as the upper limit for subsequent experiments in which we investigated the efficacies of the three compounds against HIV-1.

HMA inhibits HIV-1 replication in MDMs, as measured by p24 antigen release.

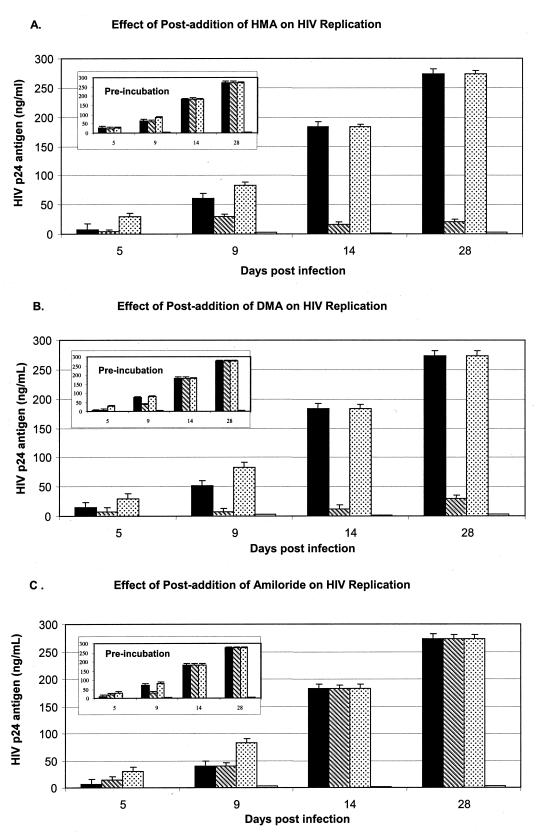

MDMs were cultured from the peripheral blood of healthy HIV-seronegative donors and infected with the laboratory-adapted M-tropic strain HIV-1BaL (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 0.02) as described previously (10). In the first set of experiments, cells from four donors were exposed to the test compounds at 0, 1, and 10 μM over 28 days. During this time, culture supernatants were periodically sampled and HIV-1 p24 antigen was quantitated by the Coulter HIV-1 p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). As illustrated for one representative donor in Fig. 3, 10 μM HMA significantly inhibited the production and the release of the virus (Fig. 3A), and this was seen with MDMs from all four donors. Virus replication was also strongly repressed by DMA at 10 μM (Fig. 3B), but no sustained inhibition was seen with amiloride (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effects of HMA (A), DMA (B), and amiloride (C) on replication of HIV-1BaL in MDMs. On day 1, 5-day-old macrophages were infected with HIV-1 at an MOI of 0.02/cell, and samples of the culture supernatant were taken at the indicated number of days postinfection for measurement of HIV-1 p24 antigen levels by ELISA. The groups of four bars for each day of measurement represent the average p24 levels for triplicate samples from cultures incubated in the presence of 1 μM HMA, 10 μM HMA, no-drug control, and 20 μM zidovudine, from left to right, respectively. The inset figures (labeled “preincubation”) show the effects of preincubation of identical cultures in the presence of the same concentrations of drug for 1 h prior to infection with HIV-1 and subsequent culture in drug-free medium. Replication of HIV-1 occurred at levels equivalent to those for the untreated controls, indicating that preexposure to compounds did not irreversibly inhibit an enzyme or damage a cellular structure necessary for HIV-1 replication or cell viability. The lower limit of p24 antigen detection is 7 pg/ml.

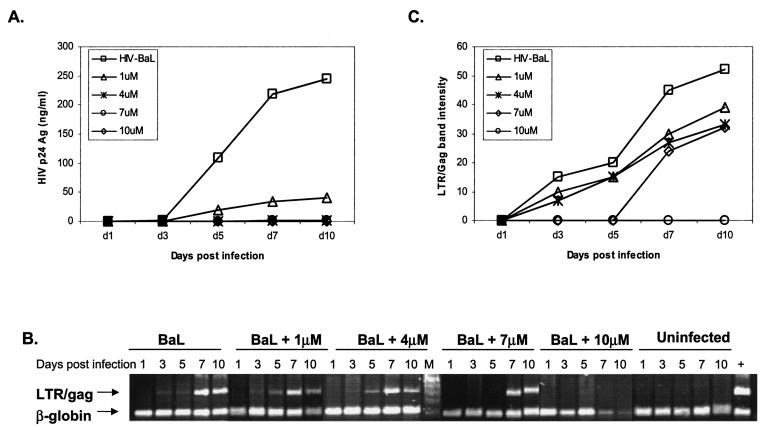

Subsequent experiments with MDMs from other donors revealed that the minimal effective inhibitory concentration of HMA is donor dependent. While 10 μM consistently showed virus inhibition, the effect of 1 μM HMA was variable (Fig. 3A and 4A). With the donor MDMs for which the results are shown in Fig. 4, significant inhibition was seen at 1 μM; and concentrations of 4, 7, and 10 μM HMA caused virtually complete suppression of p24 release (limit of detection, ∼7 pg/ml).

FIG. 4.

Effects of HMA on release of p24 antigen into MDM culture supernatants (A) and accumulation of intracellular HIV-1 DNA (B and C). Five-day-old MDM cultures were infected with HIV-1BaL (MOI, 0.02/cell) and exposed to 1, 4, 7, or 10 μM HMA for 10 days, as described in the text. Uninfected macrophages were used as negative controls, and cells infected with HIV-1BaL in the absence of HMA were considered positive controls. Either supernatants or cell lysates were collected at days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 postinfection. (A) Extracellular supernatants were assayed for p24 antigen by ELISA (Coulter). (B) Cell lysates were assayed for HIV DNA by a semiquantitative PCR with input cellular DNA. Simultaneously, a cellular 110-bp β-globin fragment was amplified by PCR. (C) The 320-bp LTR/gag band density, measured by densitometry with a Fluor-S Multi-Imager (gel documentation system; Bio-Rad), is plotted versus the number of days postinfection. By densitometry (data not shown) the β-globin band intensities are close to the control levels in all samples except those exposed to 10 μM HMA on days 7 and 10, in which a decrease of intensity of about 70% was measured. Potentially, this might indicate an increased rate of cell death for cells from this donor in the 10 μM HMA culture. Note, however, that this effect was not seen with HMA at concentrations of 7 μM or lower.

Comparison of the effects of HMA on intracellular accumulation of HIV-1 DNA and RNA versus p24 antigen release.

The amount of HIV-1 DNA inside cells was assessed by semiquantitative PCR to amplify a 320-bp LTR/gag fragment (8). Primers for amplification of a β-globin (110-bp) fragment (12) were included in the reaction mixtures to provide an internal control for the amount of total genomic DNA, a reflection of the number of cells sampled.

The HIV LTR/gag fragment was detected in untreated control cultures from day 3 postinfection, and the band intensity reached a maximum by days 7 to 10. In contrast, the presence of 10 μM HMA completely repressed the accumulation of HIV DNA (Fig. 4B). With HMA at 4 μM, with which the levels of the p24 antigen in the culture medium remained below the limits of detection over 10 days (Fig. 4A), the kinetics of HIV-1 DNA accumulation inside cells were similar to those for the no-drug control. Overall, the level of inhibition of HIV DNA accumulation in cells was not as marked as the reduction in the amount of p24 antigen released from the cells.

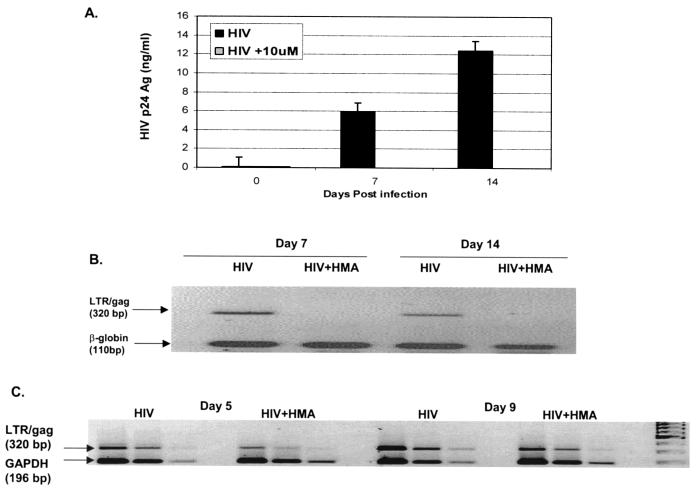

The LTR/gag fragment was also semiquantitatively amplified from HIV RNA by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (8) at days 5 and 9 postinfection. As measured by the relative intensities of the HIV LTR/gag fragment and the cellular glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or β-globin fragments, 10 μM HMA reduced the levels of accumulation of both HIV-1 RNA and DNA in the cells (Fig. 5B and C) and strongly suppressed p24 antigen release (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Effects of 10 μM HMA on production of p24 antigen (A), HIV-1 DNA (B), and HIV-1 RNA (C) in macrophage cultures. Macrophage cultures (in triplicate) were infected with HIV-1 and exposed to 10 μM HMA or the no-drug control over 14 days. (A) The levels of p24 antigen in culture supernatants, sampled on the indicated days postinfection, were measured by ELISA. As indicated, the solid bars for each day represent the results for the no-drug control and the shaded bars represent the presence of 10 μM HMA. (B) In the same experiment whose results are shown in panel A, total DNA was isolated from duplicate no-drug control and drug-treated macrophages at days 7 and 14 postinfection. PCRs were performed to simultaneously amplify a 320-bp LTR/gag fragment from HIV-1 DNA and a 110-bp β-globin gene fragment from cellular genomic DNA, and samples from the reaction mixtures were run on agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Note that in contrast to the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 4, with the cells from the donor whose results are shown here, the β-globin band intensity remains near the control level even after 14 days; this is consistent with observations that 10 μM HMA is well tolerated by MDMs from most donors. (C) Total RNA was isolated from control and drug-treated HIV-1-infected macrophages at day 5 and day 9 postinfection. RT-PCRs were performed to simultaneously amplify the 320-bp LTR/gag fragment from HIV-1 RNA and a 196-bp fragment from mRNA for the cellular housekeeping enzyme GAPDH. The groups of three lanes represent serial dilutions of the samples, used to facilitate quantitation by densitometry.

In conclusion, the Vpu ion channel-blocking compounds HMA and DMA were found to inhibit the replication of HIV-1BaL in MDMs from a number of independent human donors. Amiloride itself does not block the Vpu channel (4), nor did it inhibit HIV-1 replication (Fig. 3), indicating that the hexamethylene substituent at the 5′ amine nitrogen of HMA contributes to inhibition of both of those activities.

Both the minimal virus-inhibitory concentration and the sensitivities of the MDMs to compound toxicity showed moderate degrees of donor dependence, but with 10 μM HMA the inhibition of p24 antigen release was far more pronounced than any decrease in cell viability. Overall, although the efficacy-toxicity window for HMA is relatively narrow, the effects of toxicity were clearly dissociated from anti-HIV-1 efficacy (e.g., see Fig. 4), particularly with HMA at concentrations below 10 μM.

In separate experiments (performed for us by David Tyssen at the Victorian Infectious Disease Reference Laboratory, Victoria, Australia), HMA and amiloride were tested for their abilities to inhibit replication of isolate HIV-1237288 in the MT2 T-cell line. Neither compound showed antiviral activity at noncytotoxic concentrations. This result is in line with the findings of others that the vpu gene is important for HIV-1 replication in nondividing cells, such as macrophages, but not in T-cell lines, in which adaptation to in vitro replication can lead to the selection of mutant viruses not expressing Vpu (1, 3, 13, 15). Furthermore, mutations that ablate the Vpu channel activity are known to inhibit the virus budding step (14, 16), and while the experiments reported here have certainly not pinpointed the mechanism of action of the compounds, the observation that suppression of p24 antigen release is stronger than inhibition of HIV DNA and RNA accumulation (Fig. 4 and 5) is consistent with reduced virus budding as a result of HMA blockage of the Vpu ion channel (4).

Acknowledgments

The work described here was funded in part by an Australian Government block grant to the John Curtin School of Medical Research and in part by Biotron Limited (ABN 60 086 399 144).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balliet, J. W., D. L. Kolson, G. Eiger, F. M. Kim, K. A. McGann, A. Srinivasan, and R. Collman. 1994. Distinct effects in primary macrophages and lymphocytes of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 accessory genes vpr, vpu, and nef: mutational analysis of a primary HIV-1 isolate. Virology 200:623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr, J. M., H. Hocking, P. Li, and C. J. Burrell. 1999. Rapid and efficient cell to cell transmission of human immunodeficiency virus infection from monocyte-derived macrophages to peripheral blood lymphocytes. Virology 265:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du, B., A. Wolf, S. Lee, and E. Terwilliger. 1993. Changes in the host range and growth potential of an HIV-1 clone are conferred by the vpu gene. Virology 195:260-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ewart, G. D., K. Mills, G. B. Cox, and P. W. Gage. 2002. Amiloride derivatives block ion channel activity and enhancement of virus-like particle budding caused by HIV-1 protein Vpu. Eur. Biophys. J. 31:26-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewart, G. D., T. Sutherland, P. W. Gage, and G. B. Cox. 1996. The Vpu protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 forms cation-selective ion channels. J. Virol. 70:7108-7115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlinger, H. G., T. Dorfman, E. A. Cohen, and W. A. Haseltine. 1993. Vpu protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances the release of capsids produced by gag gene constructs of widely divergent retroviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7381-7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase, A. T., and T. W. Schaker. 1998. Potential for the transmission of HIV-1 despite highly active anti-retroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:1846-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanauer, A., and J. L. Mandel. 1984. The glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase gene family: structure of a human cDNA and of an X chromosome linked pseudogene; amazing complexity of the gene family in mouse. EMBO J. 3:2627-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klimkait, T., K. Strebel, M. D. Hoggan, M. A. Martin, and J. M. Orenstein. 1990. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protein Vpu is required for efficient virus maturation and release. J. Virol. 64:621-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naif, H. M., J. Chang, M. Ho-Shon, S. Li, and A. L. Cunningham. 1996. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus replication in differentiating monocytes by interleukin 10 occurs in parallel with inhibition of cellular RNA expression. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1237-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul, M., S. Mazumder, N. Raja, and M. A. Jabbar. 1998. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu transmembrane domain that promotes the enhanced release of virus-like particles from the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. J. Virol. 72:1270-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saiki, R. K., D. H. Gelfand, S. Stoffel, S. J. Scharf, R. Higuchi, G. T. Horn, K. B. Mullis, and H. A. Erlich. 1988. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239:487-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai, H., K. Tokunaga, M. Kawamura, and A. Adachi. 1995. Function of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein in various cell types. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2717-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schubert, U., S. Bour, A. V. Ferrermontiel, M. Montal, F. Maldarelli, and K. Strebel. 1996. The two biological activities of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein involve two separable structural domains. J. Virol. 70:809-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schubert, U., K. A. Clouse, and K. Strebel. 1995. Augmentation of virus secretion by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is cell type independent and occurs in cultured human primary macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Virol. 69:7699-7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schubert, U., A. V. Ferrermontiel, M. Oblattmontal, P. Henklein, K. Strebel, and M. Montal. 1996. Identification of an ion channel activity of the vpu transmembrane domain and its involvement in the regulation of virus release from HIV-1-infected cells. FEBS Lett. 398:12-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strebel, K., T. Klimkait, and M. A. Martin. 1988. A novel gene of HIV-1, vpu, and its 16-kilodalton product. Science 241:1221-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]